7

Snow White vs. Napoleon

Rapunzel was the most beautiful child in the world. When she was twelve years old the witch shut her up in a tower in the midst of a wood.

When Little Red Riding Hood entered the woods a wolf came up to her. She did not know what a wicked animal he was, and was not afraid of him.

Near a great forest there lived a poor woodcutter and his wife, and his two children; the boy’s name was Hansel and the girl’s Gretel.

At last the Queen sent for a huntsman, and said, “Take Snow White out into the woods, so that I may set eyes on her no more. You must put her to death, and bring me her heart for a token.”

Most of us know these stories. The words have the lyrical ring of the nursery rhyme: “Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair,” “Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” Rapunzel, Snow White, Hansel and Gretel—the characters in the Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm are part of our childhood. What befalls them—the events, the adventures—we remember with fondness, and a shiver.

But they all share one characteristic: the action is firmly set in the woods, dark and forbidding. That is where character is demonstrated and evil is overcome. These fairy tales tell the fate of imaginary figures, but they are also about the destiny of Germany. The Grimms’ fairy tales reflect national politics and indeed fears and hopes about the fate of the Germans. And one of the great traditions, or myths, of Germany is that its origins and destiny were forged—like Hansel and Gretel’s—in the forest.

Archetypally Germanic is the Teutoburger Wald, the Teutoburg Forest, about sixty miles north-east of Cologne. There are conifers, beech and oak. It is immense—green and dense, frightening and dark, with cosy log cabins and alarming wild animals. If you lose your way, you might never be seen again. It is a place of enormous national significance, for in A.D. 9 the Teutoburg Forest was the site of the great German victory over Rome, grimly reported by the Latin historian Tacitus. A massive Roman army had invaded, intent on conquering and colonizing Germany east of the Rhine. The warrior Hermann, leading an alliance of German tribes, wiped the Romans out. The forest remained in German hands; the Rhine became the frontier of the Roman Empire; the rest of Germany remained unconquered. Here, in the Teutoburg Forest, so the patriotic legend runs, a nation was born out of resistance to Roman aggression and occupation.

Jumping forward to the early 1800s, both literature and painting set out to create a sense of German-ness, as a response to foreign aggression, and both of them are also often linked to the forest. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, the aggressors were not the Romans, but their Gaulish successors, the French. And this time the French had not only attacked the Germans: they had conquered them, dismantled the Holy Roman Empire of the German nation, and occupied their homeland, from the Rhine to the Russian border.

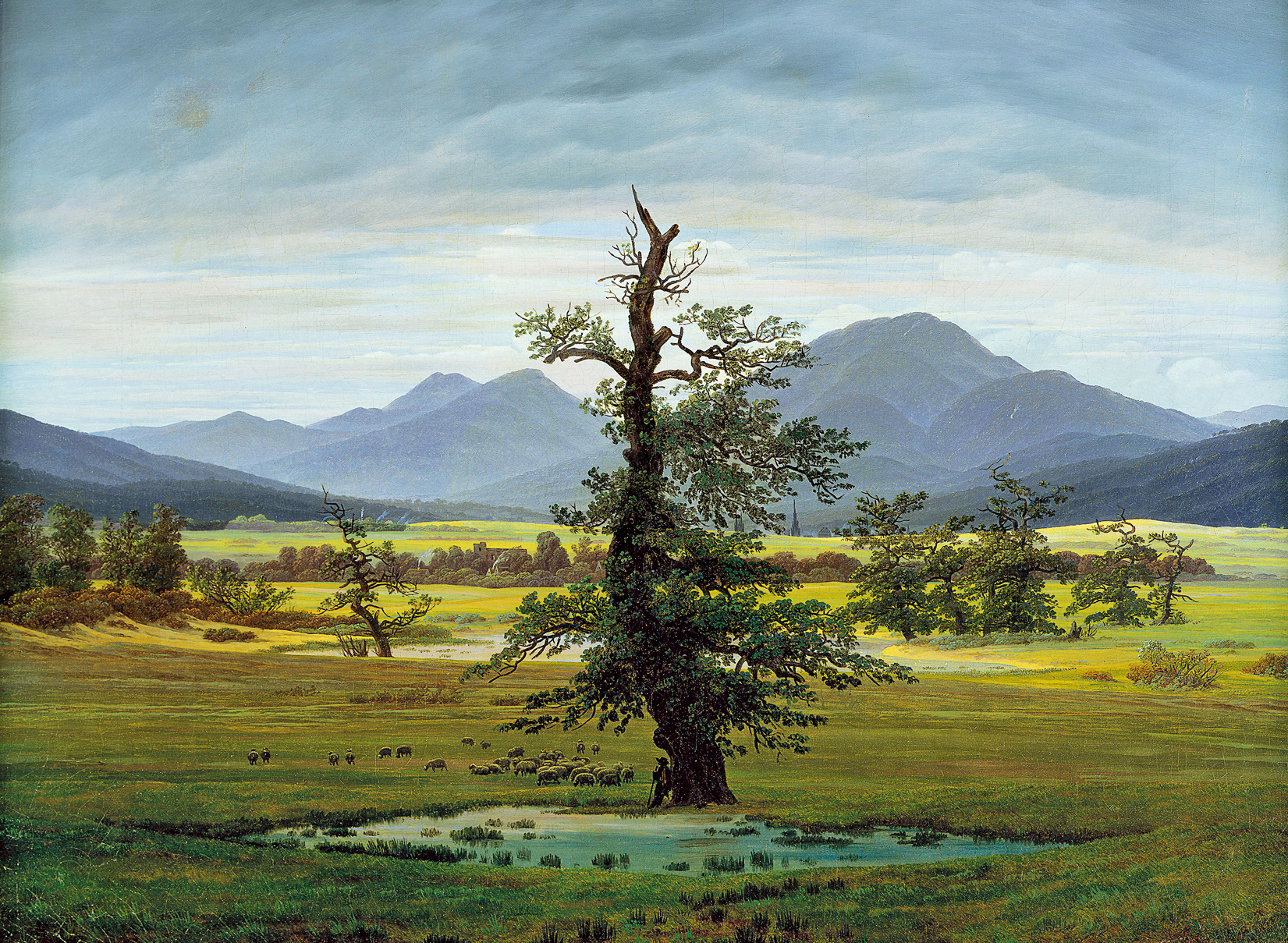

The Chasseur in the Forest, by Caspar David Friedrich, 1814 (Credit 7.1)

Early editions of Children’s and Household Tales, by the Brothers Grimm (Credit 7.2)

One book still found in almost every German home is the Kinder-und Hausmärchen—Children’s and Household Tales—as told by Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm. The Grimm brothers collected these folk tales all their lives and they produced many editions of the book. They first appeared in 1812, just as the military resistance to Napoleon was gathering strength. But the Grimms were not interested in them merely as children’s stories: their real obsession was the one thing all Germans share—their language.

Words were in their DNA. They were pioneers of the study of language and its origins. Jakob Grimm formulated what became known as Grimm’s Law, the first rule about sound change discovered in linguistics, tracing the shifting of consonants between languages—why English-speakers say fish and father, Germans Fisch, Vater, while the Romans said pisces, pater. It was a new way of thinking about language. But, above all, the Grimm brothers immersed themselves in the history of German. The creation of a German dictionary, their Deutsches Wörterbuch, dominated their lives.

Professor Steffen Martus from Berlin’s Humboldt University has published extensively on the Grimm brothers, and explains that they saw a close connection between how the German language worked and how German society functioned best:

“What is interesting about the Grimms’ research into language as well as into literary history is that they were trying to discover what could be described as ‘German,’ but always in an international context. If we look at their work on German grammar, for example, it is interesting how much time Jakob Grimm spent getting to understand that a language operates according to its own internal laws, that those laws are not shaped by outside forces, and that a language is an autonomous, living organism.

“This concept had political significance: the Grimms were saying that, just as a language has its own internal form and logic, so do societies and communities. Laws cannot successfully be imposed from outside. Political, social and linguistic history are in that sense interchangeable. Changes in German society, then, will be effective only if they come from within, in keeping with the German way of doing things, not from foreign imposition.”

In other words, the Grimms’ fairy tales were part of a German political and social renaissance, evidence that in their language and their folk tales the Germans had an identity which no foreign invader could eradicate. By 1812, France had conquered and occupied all of Germany and had annexed great stretches of the Rhineland, and Cologne was a city in France. But the Brothers Grimm saw that Germany had something of immense value which the French could not claim—an antiquity of language reaching back to the mists of pre-history. This, according to Will Vaughan, Emeritus Professor of Art History at Birkbeck College in London, is what lay behind their fascination with philology, the study of language:

“The idea that Germans had kept their original language was very important—that somehow the German language was expressive of the whole German character and psyche, because it had been the language that Germans had always spoken. One of the things that the Grimms said in their famous dictionary was: what do we have in common but our language? In the Napoleonic period there was a lot of comparing between French and German. It was claimed that the French had not kept their original language—they were now speaking a version of Latin and the original language that the Celts had spoken had been lost. So there was not this visceral connection between the French and their language that there was between the Germans and theirs.”

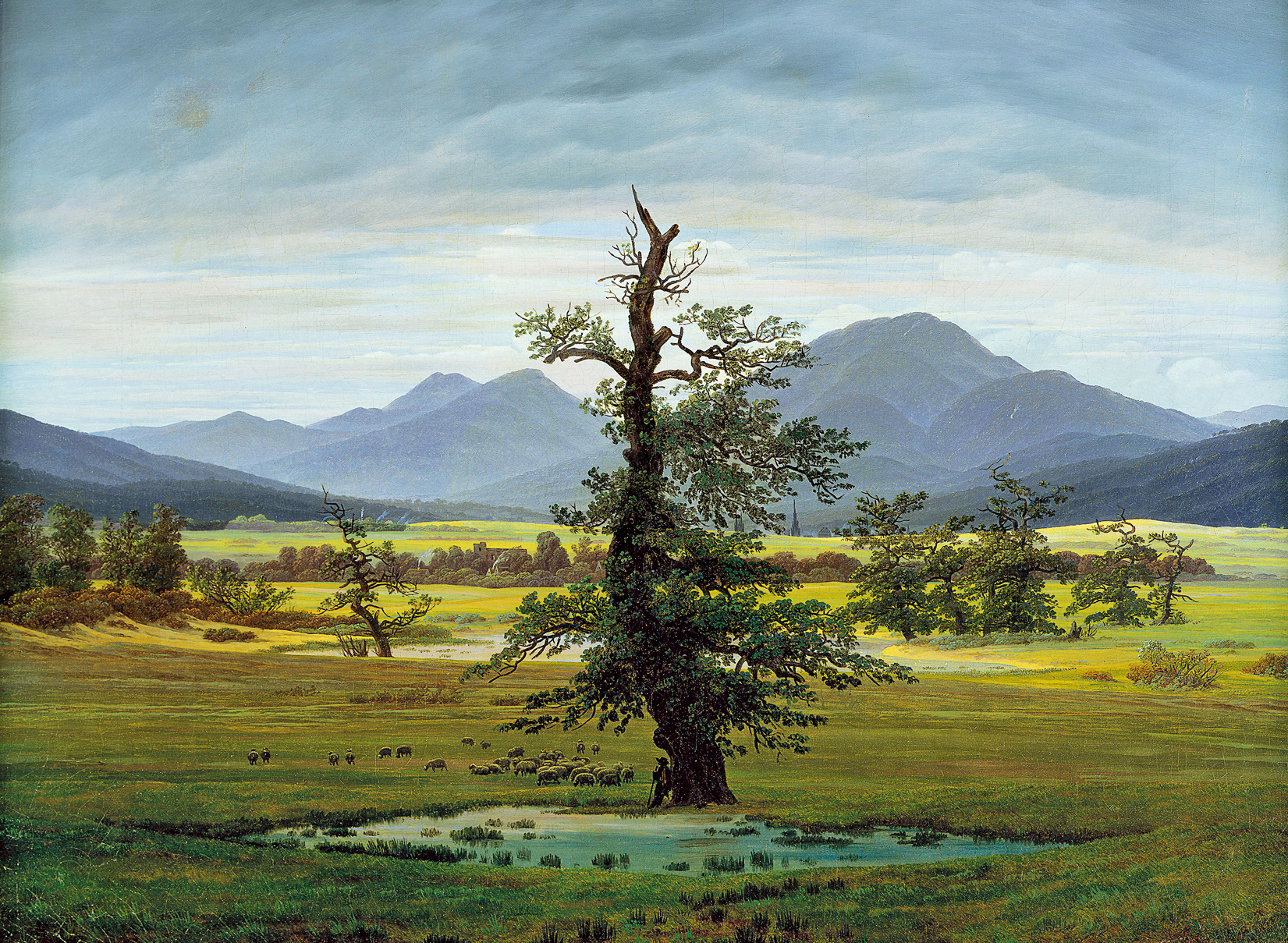

The Solitary Tree, by Caspar David Friedrich, 1822 (Credit 7.3)

Hansel and Gretel, Snow White and the other tales collected by the Grimms are not just spine-tingling yarns. In the very words, phrases and syntax is the enduring story of the German self.

The forest is as powerful a force in the painting of the period as in the literature, as we can see in a work by the great romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, Der Einsame Baum, or The Solitary Tree, painted in 1822. In the middle distance, set in a gentle green plain, is a village; in the background, a mountain range. And in the centre, in the foreground, dominating the composition, is a lone oak, its upper part battered and damaged, its lower branches in full leaf, giving shelter to a shepherd and his flock. Will Vaughan has studied the significance of this painting for German national consciousness. It brings us back to the Grimms and the forest:

“Oak is at the root of the imagery for Germans as a people who had survived all sorts of hardship. The oak tree was part of the primitive landscape. It had always been there and Germans felt that it was part of them, that it defined them in a certain way. When Hermann defeated the Romans in the Teutoburg Forest it was almost as though the forest was on the side of the Germans—they had set an ambush up for the Romans, hiding behind the trees. It is very striking that the freedom fighters of the Wars of Liberation, against Napoleon, also used the forest, and there is a wonderful picture by G. F. Kersting, a friend of Friedrich’s, called At the Sentry Post, that shows three of them leaning against oak trees, waiting for the French to come. Anyone in those days would have immediately been able to feel a national identity with the oak. Friedrich had used the oak earlier, during the Napoleonic period, for other kinds of images, but as one of a group of oaks, surrounding old graves of the ancient Germanic type—a kind of heroic monument. What is interesting in this painting is that now it is an oak standing on its own, so it has a much greater sense of loneliness than before. Maybe the painter was expressing a personal feeling here—he is the lonely old oak; or maybe he was appealing to people who shared his radical sympathies and were hoping the oak would endure.”

At the Sentry Post, by Georg Friedrich Kersting, 1815 (Credit 7.4)

The oak tree was an image taken up by Germany’s rulers on more than one occasion as an emblem of survival and rebirth: oak leaves on the Iron Cross in 1813, for instance (see Chapter 14), and on the country’s first post-1945 coins. Friedrich’s lonely oak, battered but still standing, offers shelter and nourishment in the early-morning light. It has come through the night. It has weathered the storm. Like Germany after the Napoleonic wars, it has survived.

The Grimms were studying the German language: the inner German-ness present in the folk tales they collected. Friedrich used landscape as an external vision of being German. Constable was doing something similar at the same date with his pictures of England—the Hay Wain, Flatford Mill and so on—and in each case there is an element of invention, which merely heightens the impact of these powerful national images, where landscape fuses with fantasy. Friedrich spent his life painting wild, sublime landscapes in which the individual discovers his potential and the nation does the same. Will Vaughan:

One-Pfennig coin with oak leaves, West Germany, 1949 (Credit 7.5)

“Friedrich still remains a very important artist in Germany today, because he represented the German soul in the landscape. He is a painter of the inner world as well as the outer world: it is not just the literal terrain that is being shown you, but the landscape perceived through a German soul, so it has an emotive charge to it.”

In Friedrich’s paintings the trees are sublime, in the Grimms’ fairy tales the forest is threatening. Both are editing the German landscape for their own purposes. But, as Steffen Martus tells us, they are doing more than that: they are inventing the German landscape:

“The German forests that we know today—huge woods with fir trees, and the other typical German broad-leaved trees—these were just as much an invention of Romanticism as were the fairy tales. Today’s German forests largely originated through reforestation later in the nineteenth century, and this romantic woodland project became the backdrop for literature, for fairy tales and the like. The Grimms use the forest as a kind of double-edged sword. What happens in the forest in their fairy tales is often quite dreadful, quite cruel, and this is intended to frighten children, so that, at the end of the tale, they can be calmed and comforted by their mother’s voice.”

This was a particular kind of social engineering with strong political overtones. Good and evil faced each other off in the fairy tales—the children against the evil witch, the wicked stepmother, pretending to be kind. But always, waiting at the end of the storytelling, the bürgerliche Mutti, the bourgeois German mother, with her comforting words. Solid German virtues, encoded in the language, in the stories and ultimately in the people themselves. Steffen Martus says there was a strong, and in the later editions increasingly moralistic, element in Grimms’ fairy tales, driven by the growing middle class in Germany:

“These fairy tales were not just transcribed to make for good literature with a strong poetic element, they are also morality tales. They were edited and re-edited to fit the readers’ tastes, a readership that knew romantic literature and wanted to bring up their children in the bürgerliche Kleinfamilie, the bourgeois nuclear family. This led to certain changes to the stories over time. In the early editions, the evil women were often mothers, as in the case of Snow White, for example, but later editions turned them into stepmothers: you could not have a real mother being evil in a proper bourgeois family. Take another famous story—Rapunzel. In the first edition of the tales, the evil fairy works out that Rapunzel must be having visits from men. How does she know? Rapunzel’s clothes get too tight—she is pregnant. In later editions Wilhelm Grimm deletes this whole section from the story and makes Rapunzel contradict herself to the fairy, which is how she realizes men must have been visiting. Rapunzel has been desexualized and made respectable. These are Victorian values, German style, which is one reason the stories so appealed to the British as well.”

Friedrich and the Grimms were re-establishing an identity for German-speaking people who had been dislocated when Napoleon destroyed the old Holy Roman Empire and the political structures that depended on it. They were providing an answer to the question: who are we now? Painters, historians and writers started to look back to Hermann, as a founding national figure. In 1808, Heinrich von Kleist wrote Die Hermannsschlacht, a play about that great battle in the Teutoburg Forest in which the Romans were defeated. It is a pretty terrible piece, mostly leaden anti-Napoleonic propaganda, which has gone virtually unperformed, although Friedrich was much moved by it. But Hermann, the romantic hero resurrected from the pages of Tacitus, has never lost his hold on the German imagination.

Today, over 100,000 visitors a year come to admire the colossal statue of Hermann that stands in the Teutoburg Forest, just outside the town of Detmold. Nearly ninety feet high, the bronze figure brandishes his sword—needless to say in the direction of France. Begun after the Napoleonic Wars to mark the liberation of Germany, it was completed in 1875, a grandiloquent celebration of Prussian victory over France in 1871. The Hermann monument is the perfect physical demonstration of how the patriotic stirrings of the Wars of Liberation—the impulses that moved Friedrich and the Grimms—were appropriated and coarsened by later nationalisms from the 1860s.

1857 engraving of the Grimms’ “Rapunzel” (Credit 7.6)

Graves of Fallen Freedom Fighters (Hermann’s Grave), by Caspar David Friedrich, 1812 (Credit 7.7)

Most Germans are now embarrassed by the shrill aggression of the Hermann statue, and are nervous or ashamed of the later misappropriations of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, not least by the Nazis. In 2009 there were no ceremonies here to mark the 2,000th anniversary of an event long seen as the founding moment of German national identity. But it did not go entirely uncelebrated. In Hermann, Missouri, a town founded by German settlers in the 1830s when the Hermann cult was at its height, the bimillennial was commemorated in 2009 by the erection, in Market Street, of a statue showing Hermann, conqueror of the Roman legions.

Both Friedrich and the Grimms had complicated histories in the twentieth century. Disney carried the stories—“Snow White” above all—to a worldwide audience which the brothers could never have imagined. But they had less welcome supporters too. For obvious reasons of intensifying feelings of national identity, the Nazis also loved the Grimms. They recommended that every home in Germany should have a copy of the Children’s and Household Tales. In consequence, the stories were for a later generation stained not just by this official endorsement, but by a concern that the violence and cruelty in the tales might also be an enduring trait in the national character, and one not always redeemed by traditional German virtues. That moment seems to have passed. Kinder- und Hausmärchen is now again the country’s most popular book after the Bible, says Steffen Martus:

The Hermann Memorial in the Teutoburg Forest, Detmold (Credit 7.8)

“After 1945 there was a long tradition of steering clear of the Grimms; their stories were too gruesome after the horrors of the Nazi period. But now there is a return to the older concept of the German family, pre-Nazi, and this is an interesting development. It is really interesting that in Berlin, for example, we now see a new, young middle class (we call them the Prenzlauer Berg set—successful yuppies) who have taken to reading Grimms’ Fairy Tales to their children, almost as if they want to preserve and protect the old ideal of the bourgeois family.”

Friedrich also suffered from the admiration of the Nazis and others who hailed him as a properly German national artist. But, as Will Vaughan explains, he has now come to mean something very far removed from strident patriotism:

“It is very interesting to see that Friedrich has from the 1960s onwards been reclaimed by Germans with very different views. Friedrich is seen as almost a proto-eco warrior, defending the countryside.”

The Germans’ attachment to the forest is still there, as old as the hills, or at least as the oaks, and a central part of the national character. Friedrich and the Grimms would be delighted. The forest now covers a third of the country and it is protected—the Greens have become more firmly established as a political party in Germany than anywhere else in Europe. The new nation’s future, like its past, will be lived in part in the forest. In the next chapter we will be looking at a great admirer of both Friedrich and the Grimms—a writer who himself became a symbol of a new kind of German-ness and remains the most identifiable figure in the national pantheon.

Poster for Walt Disney’s Snow White, 1937 (Credit 7.9)