TWO REBELS, JIMMY & NICK ADAMS, BECOME

HOLLYWOOD HUSTLERS,

SNARING, AMONG OTHERS, MERV GRIFFIN

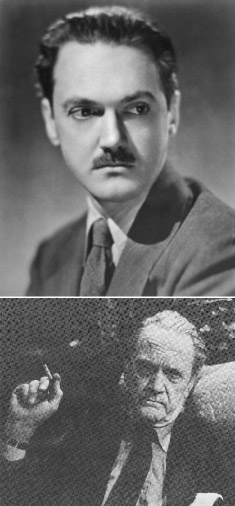

After failing at a movie career in Hollywood during the 1950s, an Irish-American from California, Merv Griffin (1925-2007), evolved into TV’s most powerful and richest mogul, eventually winning 17 Emmy Awards for The Merv Griffin Show, a durable daytime staple that attracted 20 million viewers daily.

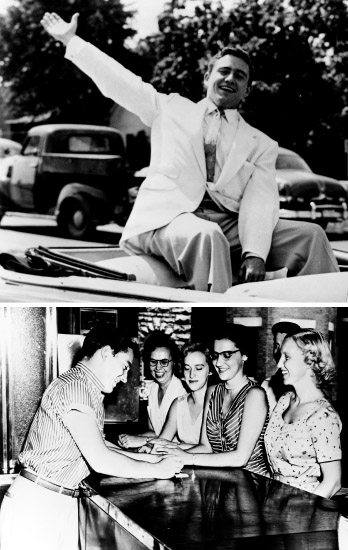

Two views of Merv Griffin in Knoxville, Tennessee, promoting his 1953 movie, So This Is Love, co-starring Kathryn Grayson. In the lower photo, he signs autographs for his adoring fan club members.

Behind the scenes, Griffin became known for his Midas touch, developing two of Hollywood’s most popular game shows, Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune.

He had first entered the entertainment scene as a boy singer with Freddy Martin’s band in the 40s.

He had long been known in the industry as a closeted gay. He married only once—it was unsuccessful—but he did produce an exceptional son from his ill-fated union.

Most of Jimmy’s fans never knew about his involvement with Griffin. The struggling actors met as neighbors in Los Angeles within the seedy Commodore Garden Apartments, when their respective careers were going nowhere. In the beginning, their trysts were sexual, for which Griffin, who had more money than Jimmy, paid his fellow actor fifty dollars per session.

At the time, Jimmy was sharing his modest studio at the Commodore Garden with another struggling actor, Nick Adams. Nick had wanted to get intimate immediately, but Jimmy had held him off until his financial situation worsened. Hard up, he accepted Nick’s invitation to move in with him.

One night, Nick and Jimmy met Griffin under unusual circumstances. Griffin had stumbled across Errol Flynn, who had passed out in the courtyard of Commodore Gardens. No longer the swashbuckling matinée idol he’d been in the 30s and ‘40s, this once perfect specimen of manhood had become dissipated after a reckless life of debauched adventures. Motivated by financial troubles, he’d checked into the Commodore. Recognizing him at once, Griffin attempted to carry him back to his apartment. At that moment, after a night of hustling along Santa Monica Boulevard, Nick and Jimmy approached.

After helping the hustlers tuck the fading star into bed, Griffin observed the two young men more closely, finding one of them particularly handsome and appealing. He extended his hand. “Hi, I’m Merv Griffin.”

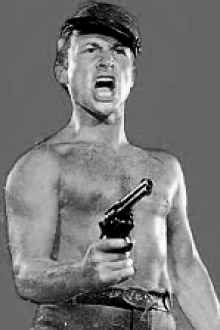

Nick Adams met James Dean in 1950, when they appeared together in a Pepsi-Cola commercial for TV. He is seen above as Johnny Yuma in his hit TV series, The Rebel.

“This here is James Dean, and I’m Nick Adams,” the taller of the two said. “We’ve seen you around.”

“Sorry we didn’t say ‘hi’ before,” Jimmy said. He looked at the body passed out on the bed. “If I didn’t know better, I’d say that was Errol Flynn—or what’s left of him.”

Jimmy and Nick seemed impatient to leave, but Griffin invited them for a drink at sundown in the courtyard the next day.

Although they arrived late, both actors showed up for that drink the next day with Griffin. He was amazed at their candor. All of them shared their various dramas in trying to find acting gigs in L.A.

“Let’s be truthful with the man,” Jimmy said. “We want to be actors. But right now, we might list our profession as hustlers.”

“I see,” Griffin said. “Are you referring to pool hall hustling, or do you mean love for sale?”

“More like dick for sale,” Jimmy said.

Years later, on his way to becoming a famous Hollywood player, Griffin described his encounters with the young actor to several of his gay friends, notably Roddy McDowall, who also knew Jimmy.

Griffith summed him up: “A slouching stance, youthful rebellion in faded jeans, a cigarette in the corner of a kissable mouth, alienation, even outright hostile at times, and the most angelic face I‘ve ever seen on a young man.”

This Dean guy is going to be a big star,” Griffin predicted. “I have this feeling about him. But he’s got a lot of weird habits. He’ll smoke a cigarette so far down that it’ll burn his lips. Yes, actually burn them with intent. He gets off on being burnt. He confessed that to me as a hustler, and for a fee, he’ll let a john crush a lit cigarette onto his butt. But he won’t allow his chest or back to be burnt in case he has to strip off his shirt for the camera—that is, if he ever gets a role.”

“The first time I was with him, even before I had sex with him, he pulled down his jeans and showed me cigarette burns on his beautiful ass. Strange boy. But I adore the kid.”

That night, Griffin was invited into Nick and Jimmy’s apartment. Jimmy wore a white Mexican shirt and new jeans, the gift of an admirer who had taken him to a clothing store. As Griffin recalled, “The whole studio smelled like the inside of a dirty laundry bag. Yet there was a sexual tension in the air.”

To Griffin’s surprise, he spotted a hangman’s noose hanging from a hook on the ceiling “That’s waiting for me if I decide to commit suicide,” Jimmy told him.

Griffin didn’t know if he were joking or if he really meant it.

As Jimmy put on a pot of coffee, Nick stripped down for a shower. Dangling his penis in front of Griffin, he said, “Now you know why I’m called ‘Mighty Meat’ along the Strip.”

After he’d showered, Nick emerged with a towel around his waist. “Being a struggling actor is like having to eat a shit sandwich every day,” he said. “It’s kiss ass…” Then he paused: “Sometimes literally. You wait for the next job, not knowing if you’re going to get it or not. Trying for a gig and having to compete with a hundred other starving actors. Congratulating your best friend when he got the job instead of you.” He glanced furtively at Jimmy and continued. “Waiting outside that producer’s door. Even worse sometimes, getting invited inside and having to submit to a blow job from some disgusting piece of flesh. And then losing the job to the guy he planned to cast all along. Trying to get a gig is half the job of being an actor. Take it from me.”

As the evening progressed, Griffin was amazed that Nick was “tooting his own horn,” sometimes at the expense of Jimmy. There was definite competition between the two actors. It was as if Nick sensed that Jimmy had far better looks and more talent than he did.

A future biographer, Albert Goldman, summed up Nick Adams: “He was forever selling himself, a property which, to hear him tell it, was nothing less than sensational. In fact, he had very little going for him in terms of looks, talent, or professional experience. He was just another poor kid from the sticks who had grown up dreaming of the silver screen.”

Right in front of Jimmy, Nick claimed that his friend would cater to kinkier offers from johns along Santa Monica Boulevard than he would. “I turn down a lot of sick queens, but Jimmy here will go for anything. One night, this weirdo wanted to eat my shit. I told him to ‘fuck off,’ but Jimmy went off with the creep in his car.”

“Why not?” Jimmy asked with a devilish bad boy look. “I hadn’t taken a crap all day.”

Years later, Griffin confessed to McDowall and to other gay friends, “Before I finished with them, I had to borrow five-hundred dollars to pay the freight, but it was worth every penny. Nick had the bigger endowment, but Jimmy was better at love-making. It was the best sex I’ve ever had, even if I did have to pay for it.”

***

Later, to Griffin’s surprise, he ran into Jimmy on the 20th Century Fox lot, where he was working as an uncredited extra.

Jimmy bonded with Griffin like a long-lost buddy, reminiscing about their encounters at the Commodore Garden Apartments. At five o’clock that afternoon, both of them headed for a drink at the tavern across the street. After his second vodka, Jimmy confessed to Griffin that he’d abandoned hustling and that he planned a move to New York in pursuit of TV and stage work.

No mention was made of Nick Adams.

Since work as an extra paid so little, and because acting gigs were so infrequent, Jimmy confessed that he’d devised a new way to make money: “I pose for nude photographs, sometimes with an erection. I’ve had a lot of copies made, and I sell them for twenty-five dollars each. It beats hustling, and no one even touches me, except perhaps the photographer. Not bad, huh?”

“Sounds like a great way for an out-of-work actor to make some extra cash, unless those nudes come back to haunt you after you make it big as a movie star.”

“Like I give a god damn about that,” Jimmy said. “I’ve set up a session with this photographer in Los Angeles. I’ve got a posing session at nine tonight. Wanna come with me?”

“I’d love to,” Griffith said. “There’s more that a bit of the voyeur in me.”

“The pictures this session are for a private collector.”

Later that evening, outside the photographer’s studio, Jimmy removed his denim shirt and blue jeans. He wore no underwear. He handed his apparel to Griffin for safekeeping. “I like to arrive at the doorstep ‘dressed’ for action.” Then he chuckled at his own comment.

At the door, the shocked photographer hustled the two men inside. “I’ve got two Eisenhower Republican old maids living upstairs. They might see you and have a heart attack. I don’t want those old biddies to know what goes on in here.”

During the shoot, Griffin assisted the photographer, fetching a glass of water or holding the spotlight. But mostly he stared with fascination at the subject.

As a nude model, Jimmy had no inhibitions. At one point, he grabbed a prop from a previous shoot, a black lace mantilla abandoned by a female model’s posing. He plucked a red rose from a vase, grasping its stem with his teeth.

“This may be too girlish a pose for your client.” The photographer warned, but he snapped the picture anyway.

At the end of the session, Jimmy put back on his clothes, and then rejected the photographer’s invitation for a three-way with Griffin.

Back on the street again, Griffin asked, “What’s next?”

“I want to go back to your place and fuck you,” Jimmy said.

“A man after my own heart.”

The pictures that Jimmy posed for that night are now in private hands, and considered a valued collector’s item.

Until its final casting was defined and publicized, Jimmy clung to the hope of starring as Curly McLain in the film version of Oklahoma! (1955). When he heard that Fred Zinnemann had been named as its director, he got in touch with him and requested an audition.

“I’ve got to be frank with you,” he told Jimmy. “I’m considering Paul Newman for the role, even though he can’t sing. I can always dub a soundtrack afterwards.”

“I can’t sing a whole lot, but I sure as hell can act the role of Curly better than any other god damn actor in Hollywood,” Jimmy said.

He was very persuasive and enticed Zinnemann into testing him out. The director had seen pictures of Jimmy and thought that from a physical standpoint, he’d be ideal for the role.

When Jimmy arrived at the director’s snobby hotel, he was almost ejected from the lobby. The staff behind the desk later claimed, “He showed up looking like a cowboy wino.”

He wasn’t allowed to pass through the lobby, but was directed to the rear service entrance, where he rode the freight elevator up to Zinnemann’s suite.

Zinnemann was impressed with Jimmy’s rendition of the “Poor Jud is Dead” number alongside the veteran actor Rod Steiger, who had also been cast.

Later, Griffin called Jimmy about getting together for a drink. [Unknown to Jimmy, Griffith had also been lobbying for the role of Curly, even though Zinnemann was insisting on a Paul Newman type.]

Griffin, a talented singer in his own right, concealed from Jimmy how much he had wanted the role. When he had met with Zinnemann, the director had rejected Griffin for the role, but suggested that he could arrange for him to be in a movie called The Alligator People instead. “Would you allow makeup to transform you into an alligator?”

Griffin had rejected the offer and headed for the door.

The role Jimmy wanted but wasn’t destined to get. Center figures: Gordon MacRae as Curly, Shirley Jones as his bride.

Over a drink with Griffin, Jimmy boasted that Zinnemann had told him that his tryout was one of the best auditions the director had ever witnessed.

“And your singing?” Griffin asked. “You can sing?”

“I’m not sure yet, but if I can pull off the role of Curly, I might become a singing star in other musicals.”

Eventually, Zinnemann opted against Jimmy, instead offering the role to Frank Sinatra, who rejected it. The director finally settled on Gordon MacCrae, an actor and an accomplished singer.

As a result, the public never had to sit through Jimmy belting out a rendition of “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning.”

***

As early autumn fell across Los Angeles in October of 1951, Jimmy prepared to leave the city. He told William Bast, “My dreams of becoming a movie star have been bashed.” He revealed that he was going to Chicago to join Rogers Brackett, who had been temporarily stationed there by his ad agency. “After that, I’m heading for stardom on Broadway, but I don’t have a lot of money.”

Bast learned that although Brackett had arranged and paid for his train ticket to New York, with a stopover in Chicago, he had given him only a hundred dollars in spending money. “He likes to keep me on a tight leash. I certainly don’t have one cent left from my work as a movie extra.”

Bast met with Jimmy for a farewell bowl of chili at Barney’s Beanery. His former roommate found Jimmy in a depressed mood. “You can knock your fucking brains out in Tinseltown. If you’re lucky, you’ll occasionally get $44 a day working as an extra in some shit movie. There’s got to be more of a future for me than that.”

“With Brackett, you’ll be singing for your supper again,” Bast warned.

“A gig’s a gig,” Jimmy responded.

“I’m not performing for Rogers anymore,” Jimmy claimed, although Bast did not find that statement convincing. “If I can’t make it in show business on talent alone, then I don’t want to be in it at all.”

Bast had been made aware of the inner conflicts Jimmy had faced about selling his body. In a memoir, he speculated, “Surely, being kept had to produce some kind of internal conflict in this Quaker-bred Indiana farm boy.”

Bast recalled a shocking scene he’d secretly witnessed which seemed to demonstrate Jimmy’s inner conflicts about renting his charms to any passerby on the street.

He had awakened one night at around 2AM, when he still shared the penthouse with Jimmy. Quite by chance, he looked out the window down onto the street scene below. There, he spotted Jimmy sitting on a bus bench, lit by a street lamp. To Bast, Jimmy was obviously cruising, waiting for a john to pull up in his car and offer him money in return for sexual favors.

Bast stayed glued to the window. Within a few minutes, a Cadillac stopped. The male driver called out to Jimmy, who rose from the bench and headed toward the car. Bast expected him to get in and ride away.

Instead, as he approached its open window, Jimmy pulled out a flick knife and seemed to threaten the driver, who stepped on the gas and sped away.

After that, Jimmy returned to their penthouse. Bast quickly retreated to the bedroom and pretended to be asleep. He didn’t want him to know that he’d witnessed the scene below.

Back at Barney’s Beanery, Jimmy looked around the room at the many out-of-work actors who had managed to scrape together enough money for a bowl of Barney’s dubious chili.

Suddenly, Jimmy’s face lit up. “I’ve got this great idea. I’ll go to New York and find us a place to live. Why don’t you follow me? We’ll be two struggling actors trying to make it in the cultural capital of the world, where our talents are sure to be appreciated.”

“That might not be a bad idea,” Bast said. “Let’s keep in touch after you get there. When you have an address, send it to me. I’ll respond at once.”

After more talk and more plans, the two men retreated to the sidewalk, where they warmly embraced for a farewell. “I hope that faggot-hating Barney isn’t watching,” Jimmy said. Then he kissed Bast on both cheeks and headed out into the fading afternoon, toward his new life.

Later that evening, after Bast had returned to his modest studio, he could hear the shouts of the spectators across the street, roaring from the American Legion Stadium, where a violent wrestling match was being staged between a white giant and a black giant.

Missing Jimmy, he fell asleep listening to the roar of the crowd. “Break his neck! Tear the fucker apart!”

It was in Chicago that Brackett made his debut into the field of television. His decision was partially based on references in The Hollywood Reporter about the challenges confronting radio from the emerging media of “the little black box.”

One of his first duties involved supervision of a show for kiddies entitled Meadow Gold Ranch. He told Jimmy, “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. Television is the medium of the future, and you should seek work in TV dramas being filmed in Manhattan.”

“But I want to become a movie star,” Jimmy protested.

“Why not a TV star?”

After his arrival in the Windy City, Jimmy entered the lobby of The Ambassador East, one of the most expensive hotels in Chicago. Dressed in jeans, he had draped Sidney Franklin’s blood-soaked matador’s cape over one of his shoulders. After registering himself into Brackett’s room, his battered suitcase was carried onto the elevator by a smartly uniformed bellhop, who Jimmy claimed “looked like a dead ringer for John Derek.”

Whereas with Bast, he had maintained the pretense that his relationship with Brackett was no longer sexual, Brackett told a different story. “I don’t think Jimmy was in the door for more than ten minutes before I had his clothes off. The pickings for me in Chicago had been lean, and I was hungry. Sex in the morning, sex when I came in from the office, and sex after retiring to bed. The kid told me I exhausted him.”

Jimmy seemed lost in the vast sprawl of Chicago and stayed mostly within the hotel room, not wanting to wander alone on his own.

During his fourth evening in town, a guest arrived at their hotel room. It was David Swift, a respected director, screenwriter, animator, and producer. He would later recall his introduction to Jimmy: “I knocked several times before this young man slowly opened the door and peered out. I think Rogers was in the shower. The kid had on this tattered old matador’s cape and seemed to be rehearsing an imaginary bullfight. Instead of telling me who he was, he shouted ‘TORO! TORO!’ I thought he might be insane.”

Suddenly, having wrapped a robe around himself, Brackett was in the room, pushing Jimmy aside. “It was then that I learned that this crazy guy was James Dean, and that he was this actor wannabe,” Swift said.

He had arrived to accompany his friend, Brackett, and Dean to the Chicago production of the controversial play, The Moon Is Blue. It starred Swift’s young and attractive new wife, actress Maggie McNamara. In a previous production that starred Barbara Bel Geddes, it had been a hit on Broadway, where it had been attacked for its “light and gay treatment of seduction, illicit sex, chastity, and virginity.”

Jimmy found the play candid and exciting and enjoyed its frank discussions about sex. He was charmed by McNamara’s performance and told her so backstage after the performance.

Maggie McNamara, as she appeared on the cover of Life magazine in April, 1950.

Over thick Chicago steaks, as Swift renewed his friendship with Brackett, McNamara and Jimmy got to know each other. Swift informed everyone that he was developing a TV sitcom, Mister Peppers, scheduled for transmission on NBC during the summer of 1952. Its star was Wally Cox.

[As a gossipy footnote, Swift claimed that Cox was the lover of Marlon Brando. That information fascinated Jimmy. It was perhaps the first time he’d heard that Brando was bisexual.]

...and years later, as she starred in an episode of The Twilight Zone (“RingaDing Girl”).

McNamara, a New Yorker, had been a teen fashion model and had appeared on the April, 1950 cover of Life magazine. She said that producer David O. Selznick had seen the magazine cover and had offered her a movie contract. “I turned it down. I’m not ready for movies yet.”

Whereas Swift had not been particularly impressed with Jimmy, he later admitted, “For Maggie and Jimmy, it was instant love. My wife just adored him and practically wanted to adopt him and make him part of our household.”

During the days ahead, while Brackett and Swift were otherwise occupied, McNamara and Jimmy set out to explore Chicago together during the daylight hours. According to Swift, “I know I should have been jealous, but Rogers assured me that Jimmy was one hundred percent homosexual. I later learned that was not true.”

Jimmy told Bast that on three different afternoons, he returned with McNamara to the suite she otherwise occupied with Swift. “We made love, and I was really into her.”

Bast speculated that “Jimmy was eager to establish his heterosexual credentials after all the gay sex he’d had. He also told me that they didn’t spend as much time exploring the glories of Chicago. Instead, they talked for hours, plotting their future careers. The two lovebirds really seemed into each other. I don’t think Swift and Brackett had a clue.”

“Whether it was true or not,” Bast continued, “Jimmy also told me that when the time came for him to say goodbye to McNamara, her final words to him were, ‘I should have married you instead of David. You and I are kindred souls.”

[Eventually director Otto Preminger would cast McNamara as the female lead, alongside William Holden and David Niven, in the 1953 film version of The Moon Is Blue. The movie challenged the censorship provisions of the Production Code of its day and was consequently banned in several states, including Maryland, Ohio, and Kansas. Preminger appealed the ban all the way to the Supreme Court and won his case. The ban was overturned, and The Moon Is Blue became credited as instrumental in weakening the influence of censorship in the film industry.

For her role in it, McNamara was nominated for an Oscar as Best Actress of the Year. She later appeared in the romantic drama, Three Coins in the Fountain (1954), and also played the lead opposite Richard Burton in a biopic Prince of Players (1955) about the mid-19th-century Shakespearean actor Edwin Booth.

Her career, however, was in serious decline by the mid-1950s, offers for acting jobs only sporadic. Preminger claimed that “Maggie suffered greatly after becoming a star. Something went wrong with her marriage to David Swift. She had a nervous breakdown.”

Her last appearance was with the silent screen great, Lillian Gish, on The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1964. After that, she faded from public view and worked as a typist until her death on February 18, 1978.

She was found dead on the sofa of her New York apartment, having overdosed on sleeping pills.]

Before establishing a life for himself in New York, Jimmy told Brackett that he wanted to return to Fairmount, Indiana, to visit his family, especially his aunt and uncle, Ortense and Marcus Winslow, who had reared him as a little boy after his mother died.

Brackett, who remained behind, bought him a round-trip ticket from Central Chicago to the train depot at Marion (Indiana), where it was understood that the Winslows would meet his incoming train.

As he rode the rails, many memories of his boyhood in the 1940s came racing back.

At this point in his life, Jimmy had not yet made any of his legendary films, nor had he yet taken Hollywood by storm. But in a short time, he would become the most famous alumnus of Fairmount. Unlike Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, he had not been born into poverty. As a teenager on a Midwestern farm, he had led a comfortable middle-class life.

His Aunt Ortense remembered him as “a pretty boy, fair-skinned, rosy-cheeked, with ruby red lips. His mother always dressed him real cute until he finally adopted his own style: Blue jeans, a white T-shirt, and boots.”

His first train ride to Fairmount had transpired in 1940, as part of his 2,000-mile “funeral cortège” from Los Angeles aboard “The Challenger.” His grandmother, Emma Dean, had accompanied him, along with the embalmed corpse of his dead mother, Mildred. It had traveled within a sealed coffin, within a car otherwise devoted to luggage.

Years had passed since his post-graduation departure from the Winslow homestead. Whereas the family’s ownership of its 14-room farmhouse had survived the Great Depression, many of their neighbors had lost their homes through foreclosures by greedy banks.

The Winslows had always been warm-hearted guardians.

In this small Hoosier town of 2,700, Jimmy as a boy raced along maple-shaded Main Street, a thoroughfare lined with staid, matronly, white-painted Victorian homes with moss-green shutters. He remembered the scene as reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell cover for The Saturday Evening Post.

Route 9 connected Fairmount with Marion, ten miles to the north, where Jimmy had lived, temporarily, with his parents.

Now, with Brackett far away in Chicago, Jimmy settled once again for a reunion with the Winslows and the circumstances of his childhood.

Within a reasonable time after his arrival, Jimmy left the house and headed for the Rexall Drugstore, where he ordered a chocolate malt. Ironically, something akin to that had been choreographed opposite Charles Coburn during his one big scene in the movie, Has Anybody Seen My Gal?

As a farm boy during his childhood, Jimmy had been taught to perform daily chores—feeding the chickens their grain, sweeping out the barn, collecting freshly laid eggs, milking cows, and helping with the spring planting. Marcus had even purchased a pony for him to ride through the fields. In summer, he fished for carp in a nearby creek.

At the local public schools, he was bright and intelligent, but often didn’t listen in class and rebelled against doing homework. He earned mostly Cs and Ds on his report card.

When he had turned fifteen, his uncle got him a summer job in a nearby factory that canned tomatoes. “I earned ten cents an hour and felt like a character in a John Steinbeck novel,” Jimmy later said.

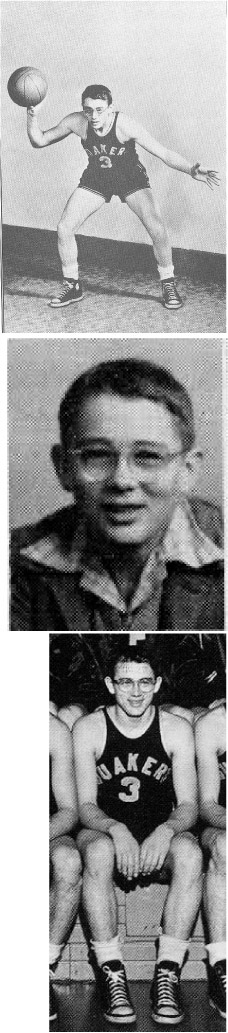

Jimmy Dean: High school basketball team member, despite his myopia.

Later, his uncle bought him a motorcycle, a model from Czechoslovakia. Once he was safely away from the sightlines of anyone watching from his uncle’s farm, he stepped on the gas, navigating around “Suicide Curve” at full throttle. Many accidents, including two deaths, had been suffered within recent memory by motorists who did not maneuver their way around the curve.

Jimmy’s fascination with motorcycles would continue throughout the rest of his life. One of his female classmates complained, “We learned to get out of Dean’s way when we heard him roaring in on that damned motorcycle. Sometimes, he seemed to be trying to run over us. He was very reckless. His accidental death was often predicted.”

Before he graduated from high school, Jimmy reached his full height of 5’8”, weighing 140 pounds.

In spite of his small stature, he excelled at sports, particularly basketball. His coach claimed that “The boy often had to jump three feet in the air, but he got the ball in the hoop. His playmates nicknamed him, ‘Jumping Jim.’ In fact, he became our champion player, in spite of the fact that he also had to wear glasses because he was nearsighted.”

“He broke his glasses faster than I could buy him a new pair,” said Marcus.

Jimmy also took up pole vaulting and excelled at that sport, too, although he quickly tired of it.

His mother, Mildred, had been the first to notice his artistic flair. In Fairmount, he had often wandered down by the creek or in the meadows, sketching landscapes and still lifes. When not preoccupied with that, he hurled himself into track and field pursuits.

***

No one would have more influence on Jimmy than the local Methodist pastor, Dr. James DeWeerd, who was viewed locally as a hero. Evoking Billy Graham, he combined dramatic rhetoric delivered with the flair of an actor.

Shortly before his fifteenth birthday, Jimmy developed a strong crush on the reverend, who seemed responsive to the needs of this cute adolescent. In his early thirties, the Wesleyan minister was known for his charisma and histrionics in the pulpit.

Jimmy’s child-molesting priest, James DeWeerd

DeWeerd had traveled widely in Europe and had once studied in England at Cambridge University. During World War II, he’d served as an army chaplain. After a serious injury, he was awarded a Purple Heart for rescuing some fellow soldiers from a fire set by the Nazi Luftwaffe.

Jimmy was fascinated by DeWeerd’s war wounds. Shortly after they met, the pastor removed his shirt and let Jimmy inspect his scars.

He could almost put his fist into the scarred hole in DeWeerd’s stomach. As he later confessed to Bracket. “I got sexually excited trying to put my fist into that hole.”

Not everyone in Fairmount succumbed to DeWeerd’s spell. Some of the older boys called him “Dr. Weird” or “Miss Priss.” At the time, homosexuality was almost never mentioned. Instead, the pastor was defined as “eccentric” rather than queer, a widely adopted synonym for homosexual back then.

DeWeerd was known to round up a carful of the high school’s top athletes and drive them to the neighboring hamlet of Anderson. There, he would watch them strip down and swim naked in the YMCA’s swimming pool. He often invited the better-endowed and/or more receptive ones to his elegantly furnished home, where he lived with his mother, Leila DeWeerd, an aging schoolteacher.

At the time, homosexuality was interpreted as “worse than communism.” One basketball player was alert to DeWeerd’s sexual preference. Years later, he told a reporter that “the good pastor was always in the locker room checking out our stuff as we wandered down the corridor, bare-ass, to the shower room. Some of the guys knew of his interest and soaped themselves up a bit in the shower, so that they could produce a partial hard-on for this preacher man.”

“He gave many of us blow-jobs back then,” the athlete claimed. “That was a good thing for some of us because gals didn’t put out much until marriage.”

Jimmy would later describe the Reverend DeWeerd to William Bast, remembering him as a handsome man and rather stocky. “He had a jovial and was very kind, very loving, and his blue eyes forgave me, regardless of what I had done.” He also recalled the pastor’s rather full and sensuous lips.

“He put those lips to work on me, exploring every inch of my body,” he confessed to Bast. “Every crevice. I lost my virginity to him.”

The doctor did more than just seduce young Jimmy. He imbued him with a philosophy of life, telling him, “The more things you know how to do, and the more you experience, the better off you’ll be—and that pertains to sexuality as well.”

DeWeerd was the most cultured man in Fairmount. He introduced Jimmy to yoga, the bongo drums, Shakespeare, and Tchaikovsky. He also introduced him to car racing and bullfighting.

An aficionado, DeWeerd showed Jimmy movies of the bullfights he’d filmed in Mexico City, Seville, and Toledo, Spain. He also had a private collection of nude pictures of well-endowed bullfighters, something that probably affected Jimmy’s life-long fascination with bullfighting.

DeWeerd also taught Jimmy how to drive. One of their shared highlights involved an excursion to the “Indy 500” races in Indianapolis. There, DeWeerd introduced him to the ace driver “Cannon Ball” Baker. According to Marcus, “When he got back home, the boy discussed nothing but car racing for days at a time.”

Jimmy was at the DeWeerd house for dinner three or four nights a week, the Winslows putting up no objection to the frequency of those visits. After the pastor’s mother retired for the evening, Jimmy and DeWeerd would read to each other or listen to classical music.

In September of 1956, DeWeerd granted an interview to The Chicago Tribune. “Jimmy was usually happiest stretched out on my library floor, reading Shakespeare and other books. He loved good music playing softly in the background., Tchaikovsky was his favorite.”

What DeWeerd didn’t tell the newspaper was that after his mother was safely asleep, he invited Jimmy to his downstairs bedroom and watched as he stripped down. He always said, “I want you naked for this workout.”

As Jimmy later confessed, “He paid lip service to me. There wasn’t a protrusion or hole that he missed.”

Sometimes, after they’d made love, Jimmy would lie in DeWeerd’s bed and indulge in what he called “spiritual talks.”

The pastor said, “All of us are lonely and searching. But, because Jimmy was so sensitive, he was lonelier and he searched harder. He wanted the final answers, and I think I taught him to believe in a person’s immortality. He had no fear of death because he believed, as I do, that death is merely a control of mind over matter.”

“On the darker side, Jimmy was a moocher. He tried to get as much from you as possible, and if he didn’t consider you worth anything to him, he immediately dropped you.”

The editor of The Fairmount News, Al Terhune, later wrote: “Jimmy was a parasitic type of person. He hung around DeWeerd a lot, picked up his mannerisms, and absorbed all he could.”

DeWeerd may not have been Jimmy’s only homosexual contact as a teenager in the process of discovering himself. Two years after Jimmy died, a fellow schoolmate from Fairmount spoke to a reporter who was researching the screen legend’s boyhood. Married and the father of two, the former athlete did not wish to be named. But he recalled seeing Jimmy behind the wheel of an emerald green- and cream-colored Chrysler New Yorker.

At one point, the schoolboy was introduced to the owner of the car, Jimmy’s new friend, a master sergeant in the U.S. Air Force.

Jimmy was said to have met him at a street fair in Marion. The schoolmate remembered the military man as good looking and well built, with a blonde crewcut. “He sure didn’t look queer to me. He was very masculine. He was frequently seen with jimmy, who was always behind the wheel driving the guy’s car around Fairmount. He visited Jimmy on many an occasion, but usually they drove off together to Marion, or so I was told. That town had a hotbed motel on the outskirts.”

Jimmy later told Brackett and composer Alec Wilder that “some Air Force guy introduced me to sodomy. DeWeerd preferred lip service.”

He also told Bast, “Penetration at first hurts like hell until you get to lie back and enjoy it—even demand it.”

***

It appears at some point that Jimmy began to worry that he was a homosexual. He had shown little interest in girls before. “He wasn’t popular with the girls,” said Sheila Wilson. “He later looked great in the movies, but back then, we were drawn to Tab Hunter and later, to Robert Wagner. They were real cute. Jimmy wore heavy glasses and he was too short for me. When he peered at me, I felt like a mouse with a hoot owl in pursuit. Before he had major dental work done, he had unfortunate gaps between his upper front teeth, a big turn-off for me.”

His most serious crush on a woman was rumored to have been with Elizabeth McPherson, who was eleven years his senior. She was a reasonably attractive art teacher who also taught physical education.

He called her “Bette,” spelling it in a way inspired by the name of screen actress Bette Davis. “One night, he took her to dine at DeWeerd’s house, and they sat at an elegantly decorated table laden with fine china, silver, and candles. She later claimed that “the pastor fluttered around like a butterfly. When he entered the kitchen, Jimmy, a clever mimic, made fun of his movements and whispered to me that he was ‘DeQueer.’”

McPherson lived in Marion and drove to Fairmount High School every day. Since she passed the Winslow farmhouse, she made it a point to pick up Jimmy as part of her morning routine and drop him off at school. Ortense didn’t like Jimmy being seen with this older woman, but apparently expressed no objection. McPherson’s husband was disabled, requiring the use of crutches to move around in the debilitating aftermath of polio.

Sometimes, Jimmy shared his sketches with McPherson. She always remembered one in particular. “He was a victim being crushed by eyeballs, no doubt a representation of the probing eyes in Fairmount who disapproved of him.”

McPherson had once been designated as the local high school’s chaperone for a group of graduating seniors on a field trip to Washington, D.C., where there were rumors that she sponsored a beerfest where all the teenagers, male and female, got drunk. She later denied that.

Apparently, according to Jimmy, they became intimate during the trip. After his first night with her, he asked her to marry him. She turned him down for two reasons: She could not divorce her disabled husband, and there was a wide difference in their ages.

As Jimmy later told Brackett, “I was still a teenager, but I came to realize that I was capable of performing sex with both men and women. I didn’t feel I had to make a choice, but could go back and forth between the sexes. Of course, because of the way men are built, they can provide that extra pleasure.”

Although she later saw Jimmy in Los Angeles after her dismissal from the high school in Fairmount, “It was more of a fun thing. I got together with his beatnik friends, and he hung out with two or three friends of mine. We had beer parties on the beach, and weekend drives to Lake Arrowhead. I think he brought up marriage once or twice, but we drifted apart, although I continued to write him letters, even on the set of Giant.”

“I did a sentimental thing,” she recalled. “During that bus ride back to Indiana from Washington, I clipped off a lock of his hair while he was sleeping. I always carried it around with me.”

A lock of hair was found in her handbag after she died in a car crash in 1990.

***

In a journal kept during his final months in Fairmount, Jimmy wrote: “Athletics may be the heartbeat of every American boy, but I think my life will be dedicated to art and drama.”

Jimmy’s speech and drama teacher, Adeline Brookshire (also known for a while as Adeline Nall), also had an enormous impact on Jimmy’s future career as an actor. In his sophomore year, he enrolled in her speech class.

Teacher Adeline Nall...”Jimmy could work me around his little finger.”

Jimmy found her diminutive, articulate, and energetic, and he later credited her with exposing him to the beauty of the English language. She was the first to interest him in acting, casting him in key roles in school plays.

“Jimmy was both difficult and a gift,” she recalled years later to a reporter. “He could be moody and unpredictable. He liked to keep people off guard, and he was often rude to attract attention. One day, in the middle of class, he offered me a cigarette. I almost popped him one for that.”

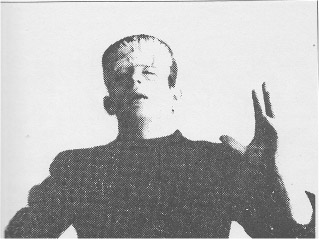

High school drama student James Dean as Frankenstein in Goon With the Wind

“If he didn’t win some competition, he would pant and rant for days at a time. I recognized a natural talent in the boy. He had it. He knew he did, and I knew it, too.”

“But he could not take criticism, which is bad for an actor. All actors face a lot of criticism, both from the press and from the public. He didn’t like to take direction from anyone. That was also bad for an actor who had to work under a director. There was another quality he had. He knew how to play people. He could work me around his little finger.”

An Unlikely Movie Star...Jimmy at Fairmount High School, watching from the bleachers.

In his sophomore year, Adeline revived that old chestnut, The Monkey’s Paw. Since 1902, it had been performed in high schools and colleges, a play with a moral that there’s nothing you might wish for that doesn’t carry bad luck with it. In this play, appealing to those with a penchant for the macabre, Jimmy was cast as Herbert White, a boy who was killed because of his mother’s foolish wish.

The following year (1947), Jimmy appeared as John Mugford—a mad old man who had visions—in the weirdly named Mooncalf Mugford. Adeline later recalled that she had to restrain Jimmy in one scene in which he practically throttled a girl cast as his wife.

That autumn, also in 1947, he appeared in the (autobiographical) play by Cornelia Otis Skinner, Our Hearts Were Young and Gay, set in Paris of the 1920s. In it, Jimmy interpreted the role of the playwright’s father, the influential dramatic actor, Otis Skinner (1858-1942).

There’s a famous photograph out there of Jimmy disguised as a Frankenstein monster in a Halloween production of Goon with the Wind. Jimmy was proud that, for his character as a monster, he had designed and applied his own makeup.

That play was followed by You Can’t Take It With You, the famous Broadway hit written by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman. [Opening on Broadway in 1936, it ran for 838 performances. In 1938 it was released as a film starring Lionel Barrymore, Jean Arthur, and James Stewart.]

In his high school’s local production, Jimmy was cast as Boris Kalenkhov, a former ballet master. As a reviewer noted, he was seen “booming about, exuberant, pirouetting.”

Jimmy’s final performance in high school play, presented in April of 1949, was The Madman’s Manuscript. It had been adapted from The Pickwick Papers, written by the then-25-year-old Charles Dickens. It was the purported memoirs of a raving lunatic, with Jimmy portraying the madman, in a grand guignol style. His most dramatic line was, “the blood hissing and tingling through my veins till the cold dew of fear stood in large drops under my skin, and my knees knocked together with fright!”

Presented before the National Forensic League [an organization whose name was later changed to The National Speech and Debate Association], he won first prize at the state level and placed sixth at the national level. He was very upset he’d lost at the national level, and blamed it on Adeline.

After his high school graduation with the class of ’49, Jimmy ranked 20th in a class of some fifty students. DeWeerd delivered the commencement address.

Jimmy told his friends and fellow seniors that he was heading for California for a reunion with his father, and that after that, he would enroll in some college on the West Coast.

His fellow seniors threw him a farewell party, at which they sang “California, Here I Come,” followed by “Back Home Again in Indiana.”

Early the next morning, with Jimmy aboard, a Greyhound bus pulled out of Fairmount. It would cross the plains of America until it reached Los Angeles. It was June of 1949. The war had ended—victoriously for the U.S. and its allies—only four years before, and young men by the thousands had flooded out of the military and into California seeking fame and fortune. Jimmy was included among those hopeful hordes.

His Indiana years had come to an end.

***

In July of 1955, Jimmy spoke flippantly about Adeline, his former teacher: “One of my teachers was a frustrated actor,” he told a reporter from Photoplay. “Of course, this chick only provided the incident. A neurotic person has the necessity to express himself, and my neuroticism manifests itself in the dramatic.”

As for Adeline, in the aftermath of Jimmy’s death, she went on to become the most celebrated high school teacher of a movie star in recent memory. She made a string of media appearances, and was featured in documentaries which included The First American Teenager (1976). She has also toured the country, lecturing and meeting fans of her former pupil and sharing stories of his first acting roles in high school dramas.

***

During his return visit to Fairmount, with his benefactor, Rogers Brackett, still conveniently far away in Chicago, Jimmy shared a reunion with Adeline Nall, his former drama coach.

As part of that venue, he addressed Fairmount High School’s small student body, talking about the Pepsi Cola commercial that had launched his career, as well as the films he’d been in, including Fixed Bayonets! and Sailor Beware. He also named and described the famous people he’d met, including Lana Turner and Joan Crawford.

He followed his short speech about breaking into the movies with the impersonation of a matador in a bullfighting ring. Donning Sidney Franklin’s blood-soaked cape, he delivered a performance that included the participation of a volunteer (a graduating senior) from the audience, who acted out the role of the bull. The show included some flashy pre-choreographed moves with Franklin’s cape which delighted the young audience.

After his speech, Jimmy played basketball with the school athletics team before heading for the showers.

After a family dinner with his aunt (Ortense Winslow) and uncle (Marcus Winslow), he headed for a reunion with the Reverend DeWeerd, which evolved into a night of sex.

The following day, at Adeline’s request, he directed the school’s drama students in a play, Men Are Like Streetcars, repeating, sometimes verbatim, the acting tips taught to him in Los Angeles by James Whitmore.

A senior drama student, Jill Corn, interpreted the role of a girl who had to be spanked. Jimmy didn’t like the way a young actor was spanking her, so he showed the class how it “was done.” He spanked Jill so hard he made her cry, and Adeline had to pull him off her.

Although Jimmy’s visit to Fairmount was short, a notification about his departure appeared in The Fairmount News: “James Dean and the Rev. James DeWeerd left Saturday morning (October 20) for Chicago, where they will transact business for a few days. Mr. Dean spent five days with his Fairmount relatives, Marcus and Ortense Winslow.”

Jimmy stayed four nights in Chicago in a B&B where he slept in a double bed with DeWeerd. He didn’t call Brackett at the Ambassador East until DeWeerd was out of town. Before the pastor left, he gave Jimmy two one-hundred dollar bills to help defray his upcoming expenses in New York.

Once back with Brackett in Chicago, Jimmy remained only four days with him before he grew restless and bored. Reacting to this, Brackett gave him a hundred dollars and a ticket to Manhattan aboard the Twentieth Century Limited.

Brackett also telephoned his composer friend, Alec Wilder, telling him to “look after Jimmy—and I don’t mean in that way!”

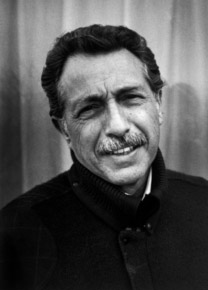

Stern, but urbane and kindly. Two views of composer Alec Wilder.

Wilder was a closeted homosexual, who liked young men as much as Brackett, but rarely did anything about it.

Before leaving Chicago, Jimmy, in the arms of Brackett, told him, “I feel I’ll meet my destiny in New York.”

***

In Chicago, Brackett escorted Jimmy to the La Salle Street Station, where he caught the 5PM train to New York, scheduled to arrive there sixteen hours later. Wilder had agreed to “take your boy under my wing and look out for him until you move here yourself.”

He had been a longtime resident of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street. This had been the gathering place of the celebrated Algonquin Round Table that attracted writers, critics, and actors including Tallulah Bankhead, Edna Ferber (Jimmy would star in the adaptation of her novel, Giant), Harpo Marx, Robert Benchley, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Harold Ross (editor of The New Yorker), and the acerbic critic and journalist, Alexander Woollcott.

Wilder was working on a musical composition when the call from Jimmy came in from Grand Central Station. “Hi,” he said. “The Little Prince has arrived in Manhattan!”

Fortunately, Wilder was a well-read man, and he understood the literary reference. “Take a taxi to the Algonquin. You’re welcome to live with me here until you settle in.”

Jimmy didn’t really know who Wilder was, but he had agreed to live with this stranger based on Brackett’s recommendation.

Born in Rochester, New York, Wilder—as a composer—was mostly self-taught. Some of America’s favorite singers, including Tony Bennett, had recorded his songs. His “While We’re Young,” had been recorded by Peggy Lee; “Where Do You Go?” had been recorded by Frank Sinatra; and “I’ll be Around” had been recorded by the Mills Brothers. Other popular songs written by Wilder eventually included “Blackberry Winter” and “It’s Peaceful in the Country.”

Over dinner in The Algonquin’s restaurant, Jimmy was blunt in questioning Wilder. “How did you meet Rogers? Were you guys lovers?”

“Friends, never lovers,” Wilder answered. “He’s a chicken hawk. I was born in 1907. One afternoon, as I was walking through the lobby here, I heard this bellowing laugh. It rang out true and honest. I felt I just had to introduce myself to this man who seemed so full of life.”

“I soon discovered that Rogers had been born in Culver City (California) and that he knew half the people who had ever walked across Hollywood Boulevard. He also knew the darkest secrets of the stars—the exact size of Charlie Chaplin’s dick; that Barbara Stanwyck was a dyke who had had affairs with Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich; that Cary Grant had fallen in love with his wife’s son [a reference to Barbara Hutton and Lance Reventlow]; and that the favorite erotic snack for Charles Laughton, Tyrone Power, and Monty Woolley usually included some variation of human feces.”

Beginning with Wilder, his first-ever contact in New York City, Jimmy started to fabricate heroic stories about his past.

According to Wilder, “I was this stranger, and he revealed to me just what a wild young man he was. One story he told me was about how he rushed into a burning building in Chicago and saved two children from being burned alive. I decided he wasn’t very bright. He wasn’t really mentally developed for a twenty-one year old. Many of the people I introduced him to swallowed his tales hook, line, and sinker. I never did.”

After his first day and night with Jimmy, Wilder wrote Brackett saying, “I’m happy to oblige your request, and I’ll look after the boy. He’s certainly not the shy type. He parades nude around my suite. I will tell you what you already know: This is a very neurotic boy, a really mixed-up kid. He tries to con everybody. There isn’t an ounce of maturity in him. I suspect there never will be. He’s also reckless, running out in front of moving traffic with this god damn matador cape, treating cars like they’re oncoming bulls in the ring. Rogers, you can’t be serious about this kid.”

Wilder continued: “The spilled blood of the matador seems to hold endless fascination for him. One night, I found him sticking safety pins into himself. He told me he wanted to increase his tolerance for pain.”

During the previous two days, Jimmy continuing an ongoing rant about bullfighting, making the claim to Wilder that in Mexico, “I actually danced with the most ferocious bulls in the arena.

He claimed that he was going to use the rhythmic movements of the matador as part of his stage work,” Wilder said. “He then gave me what he called ‘the look.’ That was when he put his head down with his eyes looking up. He then stared at me like I was the bull about to die. I thought he was crazy.”

When Jimmy wasn’t with Wilder, he went to the movie theaters, alone, near Times Square. Once again, he sat through A Streetcar Named Desire, focusing on the performance of, among others, Marlon Brando. More than once, he entered one of the theaters at 1PM and left around nine hours later. For food and drink, he purchased three cokes and two bags of popcorn, which collectively comprised both his lunch and dinner.

In addition to Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Jimmy became fascinated with another movie that would impact his acting style. It was the 1951 release of A Place in the Sun, directed by George Stevens and starring Montgomery Clift, Elizabeth Taylor, and Shelley Winters. All three actors would eventually play a role in Jimmy’s life during the months to come.

Movies and players that deeply influenced Manhattan newbie, James Dean: Montgomery Clift & Elizabeth Taylor in A Place in the Sun

A Place in the Sun was a cinematic adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s novel, published in 1925, An American Tragedy.

Jimmy was mesmerized by Clift’s brilliant performance alongside the luminous beauty of Taylor. He was also impressed with Winters’ portrayal of a plain, ordinary-looking girl who gets pregnant and is subsequently drowned so that Clift can clear his road to marriage with the rich, beautiful, and socially connected girl played by Taylor. Ultimately, however, his murder of the girl played by Winters leads to his execution in the electric chair.

The day after watching the movie, Jimmy visited a library and checked out a copy of the original novel by Theodore Dreiser, reading it cover to cover in three days.

His deep regret was that he had not been awarded the role of the doomed lover played by Clift. He poured out his frustrations to Wilder. “I think you could have done it,” Wilder said. “After all, the role calls for a man who is both masculine and sensitive, in need of a lot of mothering.”

“The part would have fitted me like a second skin,” he responded. “I’m jealous of Clift. A Place in the Sun has made him a major star.”

Months later, Jimmy watched in dismay as both Brando and Clift lost their bids for an Academy Award, the Oscar going instead to Humphrey Bogart for his role in The African Queen.

At the time, Jimmy didn’t realize that eventually, he would become intimately involved with both Brando and Clift.

Alec Wilder wasn‘t the only composer Jimmy met during his early days in New York City.

One day, Jimmy—jobless, hungry, completely broke, and strolling along Bleeker Street—wanted to stop at one of the cafés for a sandwich.

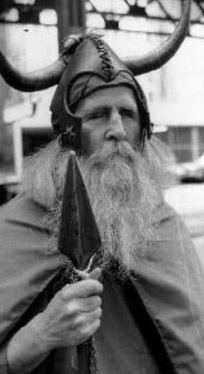

Suddenly, as if in a mirage, he heard the sound of a drumbeat coming from a strange-looking sidewalk musician. He wore a dirty, tattered cloak and a Viking helmet with horns. He had a long, scruffy beard and was obviously blind.

Jimmy introduced himself to Louis Thomas Hardin, learning that his nicknames included “Moondog” and “The Viking of Sixth Avenue.” Moondog’s usual turf stretched along three blocks of Sixth Avenue between 52nd and 55th Streets, where he spent his time selling sheet music and panhandling. Often, he just stood still, silently accepting the dimes and quarters that passers-by dropped into his basket.

Drawn to the outcasts of the world, the more bizarre the more intriguing. Jimmy, with Moondog, soon developed an “odd couple” friendship. Jimmy learned that he’d been born in Kansas and had started playing the drums at the age of five. He’d made his first drum from a cardboard box. When his family moved to Wyoming, he had a tom-tom made from buffalo skin. At the age of sixteen, he’d lost his eyesight in a farm accident that involved an exploding dynamite cap. He later learned some music theory from books printed in Braille.

During World War II, he moved to New York, where, in time, he met jazz performers who included Benny Goodman and Charlie Parker. Even Arturo Toscanini and Leonard Bernstein befriended him.

“Moondog,” depicted above, was a blind musician whose performance art was often accompanied by rhythms from Jimmy as a street musician playing his bongo drums.

He made a living by selling copies of his poetry and (heavily edited) articles about musical philosophy and by performing in street concerts.

In time, Jimmy got to know him better and would soon seek him out. At first, he thought he was homeless, but found out that he occupied an apartment on the Upper West Side. Once, Jimmy visited him there. Moondog told him that his music was usually inspired by the traditions of the Native Americans he’d met in Wyoming, with input from classical music and contemporary jazz. “I mix all that with sounds I hear on the street—the noise of traffic, the sound of a baby crying.”

“The chatter of wives at an open market, the melody of ocean waves, the rumbling of trains on the subway, the eerie lament of a foghorn in the harbor. When I put it all together, I call it ‘Snaketime.’”

He showed Jimmy instruments he’d created, one of which was the “Trimba,” a triangular percussion instrument.

On a few occasions, Moondog allowed Jimmy to participate, for tips, in street concerts. Jimmy would play his bongo drums.

“I remember one cold winter day, we’d been making music out on the street for hours—me on guitar, Jimmy on bongos,” Moondog said. “We’d made about two dollars each. I said, ‘Let’s split and get some food.’ I spent my money in a coffee shop, but he decided to go hungry and see a movie instead.”

***

One afternoon, as Jimmy and Alec Wilder were returning from lunch, they were walking through the lobby of the Algonquin. Coming toward them was the formidable Tallulah Bankhead, one of Broadway’s great leading ladies, an actress known for her husky (and much-satirized) voice, her outrageous personality, and her devastating wit. She was also notorious for her private life, having nurtured a string of affairs with some of the leading men and ladies of the screen and stage. Her conquests had included Sir Winston Churchill, Marlon Brando, Johnny Weissmuller (“Me, Tarzan!), and Hattie McDaniel, who had played Mammy in Gone With the Wind.

Unknown to Wilder, Jimmy already knew Bankhead, having met her at the home of Joan Davis when he was dating her daughter, Beverly Wills. Davis had become a regular on Bankhead’s talk radio show.

There in the lobby, to Wilder’s surprise, Jimmy made a running leap toward Bankhead, jumping up into her arms and wrapping his own arms around her. Wilder was stunned by this, and surprised that his trajectory hadn’t knocked her down.

Then he kissed her passionately. “When they became unglued, I didn’t ask how they knew each other,” Wilder said. “But we did accept her invitation to a small private party later that night in her suite.”

At 9PM Jimmy, with Wilder, knocked on the door of Tallulah’s suite at the Algonquin. The sounds of a raucous party could be heard. To the surprise of both men, when she opened the door, Bankhead was completely nude. “Come in, Dah-lings,” she said. “The party is well underway, although so far, no one’s fucked me yet.”

Then she looked Jimmy up and down. “Perhaps my luck has changed.”

Jimmy was flabbergasted that she’d be the hostess of a party in the nude, but Wilder was well aware of her antics.

When Bankhead darted off, Wilder engaged in a dialogue with Mabel Mercer, the cabaret singer. Jimmy wandered off among the thirty or so guests.

At one point, he encountered Helen Hayes. Although he hadn’t seen any or her movies or stage performances, he recognized her face from the newspapers. She was the great doyenne of the Broadway stage, a distinguished actress short of stature and big on talent.

In a soft voice, Hayes said to Jimmy, “I told Tallulah that nudity was all right within the privacy of her suite. But I warned her to stay in her room and not run up and down the corridors in an undressed state.”

“Good advice,” Jimmy said, before moving on.

AT one point, Tallulah sought Jimmy out. Taking him by his arm, she led him across the room, where an actor who looked like John Barrymore stood by himself nursing a drink. “Mr. Dean, this is John Emery, my former husband. I divorced him in Reno in 1941.”

After shaking Emery’s hand, Bankhead made an impressive move. She unzipped her former husband’s pants and pulled out a large, uncut penis. “Look at this whopper, darling.” She said. “A two-hander, even though it’s still soft. You don’t encounter one of these monsters that often.”

Smiling politely, Emery replaced his penis and zipped up again. “Oh, Tallulah, you must control yourself.” He didn’t seem all that embarrassed.

Jimmy suspected that that outrageous bit of schtick had been repeated many times during the course of their marriage.

The party wound down at around midnight. Before he exited, Wilder asked Jimmy, “Are you coming?”

“I’ll be back soon,” he said. “Tallulah has invited me to her bedroom. I’ll catch you later.”

At around 5AM, Wilder was awakened. Switching on the light, he saw a battered Jimmy. He didn’t have much to say. But later that morning, over breakfast, he was more talkative about what had transpired.

“Ever since I first met Tallulah, I had this fantasy about my sticking my dick into that luscious mouth of hers.” Jimmy confessed. “It has something to do with the way she moves her lips. Well, last night, my fantasy came true, plus a lot of other nightmare I didn’t contemplate. She complained that I almost choked her to death with an explosion of cream. She said it was at least as thick as the cream her old Alabama cow, Deliah, used to give when she was a girl growing up in the South.”

Three nights later, Bankhead called, inviting Jimmy and Wilder to join her at Norma’s Room, a nightclub in Harlem, a cabaret that attracted black entertainers, including Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, and Nat King Cole.

Before the night was over, Bankhead herself rose to perform on the small stage at Norma’s. She danced the Black Bottom and sang her theme song, “Bye Bye Blackbird,” followed by hilarious impersonations of Ethel Barrymore, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Bette Davis.

As a spontaneous climax to her equally spontaneous act, she turned three cartwheels, demonstrating to the audience that she’d forgotten to wear panties.

After that night in Harlem, Bankhead faded from Jimmy’s life as fast and as impulsively as she’d entered it.

***

[In the early 1960s in Key West, Bankhead was escorted to a party at the home of a local designer, Danny Stirrup. Her escort was the novelist James Leo Herlihy, who had just directed her in the touring play, Crazy October.

At one point during the drunken evening, Darwin Porter asked her, “Is it true that you actually knew James Dean? Or is it only a rumor?”

“No, Dah-ling, it’s the deadly truth. I got to play with his bongos and other things. He returned the favor. But he had to go and ruin it by telling me, at the end of the evening, that my mouth reminded him of Edith Piaf’s.”

Weeks after Jimmy’s death, Porter was with another novelist, James Kirkwood, during a visit to Bankhead’s apartment in Manhattan. During their visit, she claimed that she was heartbroken when news came over the TV that Jimmy had died in a car crash. “God has taken away one of his most talented and most beautiful children.”

***

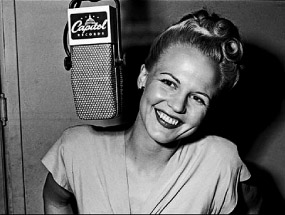

One night, Wilder invited Jimmy to go with him to hear his dear friend, Peggy Lee, perform at a nightclub. Jimmy was thrilled with the invitation, since Lee was one of his favorite singers.

Seated at a front row table, Wilder was delighted when she chose to sing something he himself had written and composed, “That’s the Way It Goes,” followed by his big hit, “While We’re Young.” Jimmy, as he later described them to Wilder, found the lyrics “laden with longing.”

For years, he’d read about Lee, who had been dubbed “The Queen” by Duke Ellington. She numbered Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra among her friends. Even Albert Einstein adored her. The press often documented her love affairs, including her on-again, off-again liaison with Sinatra.

To Jimmy, she seemed to sing and speak at the same time. He found her oval face beautiful, with a glittering, seductive aspect. She’d once been described as “perky, pretty, and bouncy, but genuinely soulful, world-weary, and resigned.”

Before she joined them at table after the show, Wilder told him, “Peggy lives on the dark, moody side of the boulevard of broken dreams.”

Shortly before midnight, Wilder and Jimmy welcomed her to their table. She and Wilder embraced like old friends, and Jimmy impulsively kissed her on both cheeks. “You are my dream lady,” he said.

He listened as both Wilder and Lee discussed Sinatra. “We have this mutual admiration society,” she said. “That is, when we’re not fighting. Frankie’s got a temper, as you well know.”

“The Primal Male meets the Primal Female,” Wilder said. “Your personalities just had to mesh. That is, until you guys have one of those knock-out, drag-out fights.”

Jazz singer Peggy Lee gave Jimmy “fever.”

“No human being can live with either of us for long,” she said.

When Wilder departed for the men’s room, she turned all her attention to Jimmy. “Could I come by your suite tomorrow night and be your escort to your show?” he asked.

“If it wouldn’t make Alec jealous, I’d be honored,” she said. “Is he in love with you?”

“It didn’t work out,” he said. “I’m staying with him at the Algonquin. Our relationship is totally one-sided.”

“You mean he gives you a blow-job and then calls it a night?” she asked. “I know Alec very well. I even know about his tragedy. Why he’ll never be a lover.”

“You mean…?”

“Exactly,” she said. “He admits he has the world’s smallest penis. He gets his satisfaction getting oral with some young stud like you.”

“A terrible affliction,” he said. “But he has to live with that. Fortunately, I don’t have that problem.”

“You’d better not,” she answered. “Life is too short for me to waste my time on trivia. Tomorrow night is fine. Come by at seven.”

The following night, Wilder was scheduled to attend a private dinner with the distinguished cabaret artist Mabel Mercer, whose loyal following included everyone from Sinatra to a coven of gay devotees. Wilder had written her signature song, “Did You Ever Cross Over to Sneden’s”

Jimmy told him he’d go to the movies, but at seven, he arrived at Lee’s suite at the Sherry Netherland and was shown in by a maid. When Lee appeared, he kissed her on both cheeks. For the first time, he saw her without makeup. To him, she looked like a homespun girl from the plains of North Dakota, where she’d been abused by a wicked stepmother, or so he’d heard.

In anticipation of her act, within her hotel suite, Jimmy watched her as she transformed herself into a glamorous figure, carefully coiffed and made up. She said that earlier, without makeup, on an elevator, a woman had asked her, “Are you Peggy Lee?”

“’Not yet,’ I told her,” Lee said. “’Catch me later, darling.’”

Miss Peggy Lee. “Until we meet again,” she told Jimmy.

Satisfied with her makeup, she told Jimmy to “Pour me a cognac, and don’t be stingy, baby. That’s a line I learned from a Greta Garbo movie.”

She informed him that before going onstage, she belted down a few cognacs to lubricate her throat.

He hailed a taxi to take her to the theater. Backstage, he accompanied her to her dressing room where she went through another elaborate check of her makeup and costume. He then accompanied her to the edge of the sightlines of the stage. Along the way, she hugged each of her musicians.

Standing in the wings, ready to go on, she breathed heavily in and out, and that seemed to give her a burst of energy. Then she muttered a soft, intimate prayer.

He heard the announcer: “Ladies and gentlemen, it is my great pleasure to welcome the lady and the legend, Miss Peggy Lee!”

There was an enthusiastic reception as she walked onto the stage, illuminated by spotlights. She let out what sounded like a small scream and stamped her high heels on the floor as she burst into song.

She opened her act with her big hit from 1942, “Somebody Else is Taking My Place,” followed by her 1943 hit, “Why Don’t You Do Right?” That song had sold more than a million copies and had made her famous.

Later that night, he accompanied her back to her suite.

When William Bast came to live with him in New York, in reference to his sexual interlude with Lee, Jimmy told him, “I was nervous at first. After all, I was told that Frank Sinatra was a tough act to follow.”

“In front of me, she defined her post-performance sexual workout as ‘a coolout.’ She was winding down. Actually, she was quite funny, doing an impression of what chickens do in North Dakota when it rains. ‘They stand in the downpour and drown,’ she told me.”

“Our evening was great, some moments sublime,” Jimmy claimed.

At one point, she admitted that her taste in men hadn’t been very good except for her first husband, Dave Barbour, the guitarist and composer whom she claimed she still loved. “Finally, by one o’clock that morning, we did the dirty deed, and she made me feel like a real man. She’s not devouring like Tallulah Bankhead. Yet she is demanding in a soft way. She aims to get her satisfaction, and with me, she did. In fact, before I left her suite, I proposed marriage to her,” he told Bast.

“She didn’t outright reject me, but was very kind. She said, “Jimmy…oh, Jimmy. You sweet, vulnerable, dear boy. I adore you. But marriage would ruin everything for us. Let’s be really close friends who get together every now and then for a good fuck.”

“Okay!” he said, before passionately kissing her goodbye.

Before he left, she said, “I have this very strong feeling about you. That you’re going to make it big in the movies. I sense a great deal of hidden talent in you. You’re going to become Mr. James Dean, not Mr. Peggy Lee.”

***

The singer published her memoirs, Miss Peggy Lee, in 1989. She remembered Jimmy, relaying a rather vanilla description of their relationship. [She was not a “kiss-and-tell” kind of author.]

During his filming of East of Eden for Warners, he visited her several times on the set of Pete Kelly’s Blues (released in 1955). She played an alcoholic singer, a role that would lead to an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actress.

One afternoon, Jimmy watched her perform in a scene where she had to sing off-key and out of tempo. “That must have been hard for you to pull off,” he said. “You’re always on key.”

She introduced Jimmy to the stars of the film, including Edmond O’Brien, Lee Marvin, and a very flirtatious Janet Leigh. Martin Milner, another star in the film, was already known to Jimmy. In October of 1951, each of them had appeared in two separate teleplays. But whereas Milner had star roles, Jimmy was assigned small, uncredited parts. Milner eventually got together with Jimmy and recalled how they’d first met:

[In midtown Manhattan, at Cromwell’s Pharmacy, hanging out with other actors, Jimmy’s first TV role came from a pickup one afternoon when he was nursing a coke. It wasn’t from a gay producer or director, but from a fellow actor, Martin Milner.

Four years older than Jimmy, Milner still had a boyish quality to him that Jimmy found appealing. Jimmy knew who he was, having seen him in the 1947 film, Life With Father, where he’d played John Day, the red-haired son of William Powell, with Irene Dunne cast as his mother.

The film also starred a very young Elizabeth Taylor. Perhaps as a means of asserting his macho credentials, Jimmy boasted to Milner, “One day, I’m gonna fuck that gal.”

“Well, until she comes along, why not fuck me?” Milner asked.

"You sure get to the point, man,” Jimmy said.

“I’m from Detroit, but I was raised in California,” Milner said, as a sort of justification. “We move in fast when we’re horny.”

“Your timing is perfect,” Jimmy said. “I have the hots, too."

“Let’s go back to my hotel,” Milner said. Jimmy followed along.

After the sex, the two young actors discovered that they genuinely liked each other, and that they wanted to be friends. They retreated to a movie together and later shared dinner together.

Milner told him that Frank Woodruff, who functioned at the time as both producer and director of the teleplay T.K.O. (Technical Knock-Out), was going to film a teleplay for the Bigelow Theater. “I think I can get Frank to cast you in a part. It’s just a small role, but at least it’s work.”

The next day, he introduced Jimmy to Woodruff, who had been cast into one of the teleplay’s minor parts. In it, Milner played a teenager who becomes a boxer to raise money for his father’s expensive operation.

Jimmy’s role was so small, he later told friends, “It’s hardly worth mentioning.”

He and Milner continued to see each other “for sessions in anatomy.” Although they each asserted to the other that he wasn’t gay, neither seemed to see anything wrong with two heterosexual actors “having a little gay sex on the side.”

Milner liked Jimmy so much, he even got him another small role in a TV series that has virtually disappeared from Jimmy’s radar screen. No biography seems to mention it, although his film clip with Milner is sometimes included in latter-day anthologies of Dean’s early TV work.

Milner had signed to appear in two episodes of a popular TV series, The Trouble With Father, starring Stu Erwin as a bumbling dad. Jimmy was hired for a role. He appears with Milner, who played Drezel Potter, the boyfriend of Joyce, a high school student whose father is Erwin. In their respective roles, Milner speaks of his love for Joyce, and Jimmy worries that he’ll never find anyone to love him.]

Martin Milner, later best known for his steady roles as a staple in Route 66 (1960-64) and Adam-12 (1968-75). Jimmy found him “boyishly comforting with an adorable innocence.”

In her autobiography, Peggy Lee wrote: “Jimmy used to come over to visit me in my trailer while I was filming Pete Kelly’s Blues. He’d arrive like a friendly cat. We were two shy people in a little room being comfortable with each other. Jimmy was always speeding around in his car, and it worried me. He was to die in a crash in Paso Robles before he completed Giant, his last film. He was unusually quiet, an intense person, and he wanted to be friends with me. He was one of those people you could not forget. You could feel things simmering and sizzling inside him, and his silence was very loud.”

***

During his first days in Manhattan, Jimmy admitted, “I was overwhelmed by the city. It’s a frightening place. I rarely left the area around Times Square.”

Eventually, he began to branch out, getting up early one morning and walking all the way to the Battery [Manhattan’s southernmost tip] where he rode the ferry to Staten Island. Once he rode the subway to Brooklyn, continuing all the way to Coney Island, where he ordered a hot dog.

He had arrived in New York with about five hundred dollars in his pocket. He later said, perhaps in exaggeration, that “I spent at least three-fourths of that watching movies to escape from my isolation, loneliness, and depression.”

He knew the time had come for him to move out of Alec Wilder’s suite and into cheaper lodgings. As he later claimed, “Alec was falling in love with me, and I could not reciprocate. I no longer paraded nude in front of him. I didn’t want to throw temptation at him. The last couple of times he tried to make love to me, I was as limp as a dishrag. It was all so embarrassing.”

When he informed Wilder that he planned to move out, the composer recommended the Iroquois Hotel, almost immediately next door, also on East 44th Street. It was clean and decent, but much cheaper. Dating from 1899, the Iroquois was one of the most historic in New York City.

During his first night there, he met the actress Barbara Baxley in the lobby. Born in California, Baxley, a life member of Actors Studio, was one of Tennessee Williams’ favorite actresses. She appeared in the Broadway production of his comedy, Period of Adjustment.

In Key West during the filming of a movie based on Darwin Porter’s bestselling novel, Butterflies in Heat, Porter invited both Baxley and another star of the movie, Eartha Kitt, for dinner at a popular local restaurant, The Pier House. Over drinks, both women discussed their emotional and sexual involvements with Jimmy. But whereas Kitt had developed a deep friendship with the actor, Baxley said that she never really got to know him. Ironically, she would eventually be cast as the malevolent nursemaid in East of Eden.

“When we first met at the Iroquois, I didn’t know who he was, and he sure as hell didn’t know who I was either,” Baxley said. “We spent a weekend together. He was very frank, telling me he needed to reassert his manhood ‘after having to service so many faggots.’ Those were his words—not mine.”

Barbara Baxley...An affinity for gay men

Baxley found him amazingly candid when speaking about himself. He told her, “I’m serious minded, an intense little devil, terribly gauche and so tense I don’t see how people stay in the same room with me. I know I wouldn’t tolerate myself, if I had a choice.”

He also told her, “I know the best is yet to come for me in my career. But I also know that when stardom arrives, it will be one hell of a disappointment.”

Baxley also confessed that she wanted the relationship to last “at least through a season,” but I knew I could never hold onto him. He wanted to wander, and there was no way in hell I could change his mind.”

“I didn’t find out about all the gay stuff until later. I was used to homosexuals, having been surrounded by them all my life. I never criticized a gay person.”

Installed at last in his new, and private, lodgings, Jimmy seemed to adopt as his own the rhythms of New York—a city that never sleeps. He became an insomniac, roaming the streets after dark, stopping in at late-night cafés and taverns, nursing a drink in one dive after another for many hours at a time. In California, he’d been tanned and healthy-looking, but he soon took on that New York pallor, and even developed bags under his eyes based on the cigarettes, coffee, and liquor he consumed late at night.

Even though he lived only a few doors away, Jimmy could be seen on most days sitting on the bellhops’ bench at the Algonquin, watching well-heeled guests come and go.

Sometimes, Wilder joined him there, later recalling that he was brilliant at impressions. “He could imitate everybody from Cary Grant to Jerry Lewis. But his best were Laurence Olivier as Heathcliff and Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara.”

As Wilder remembered it, Jimmy constantly bragged about himself.