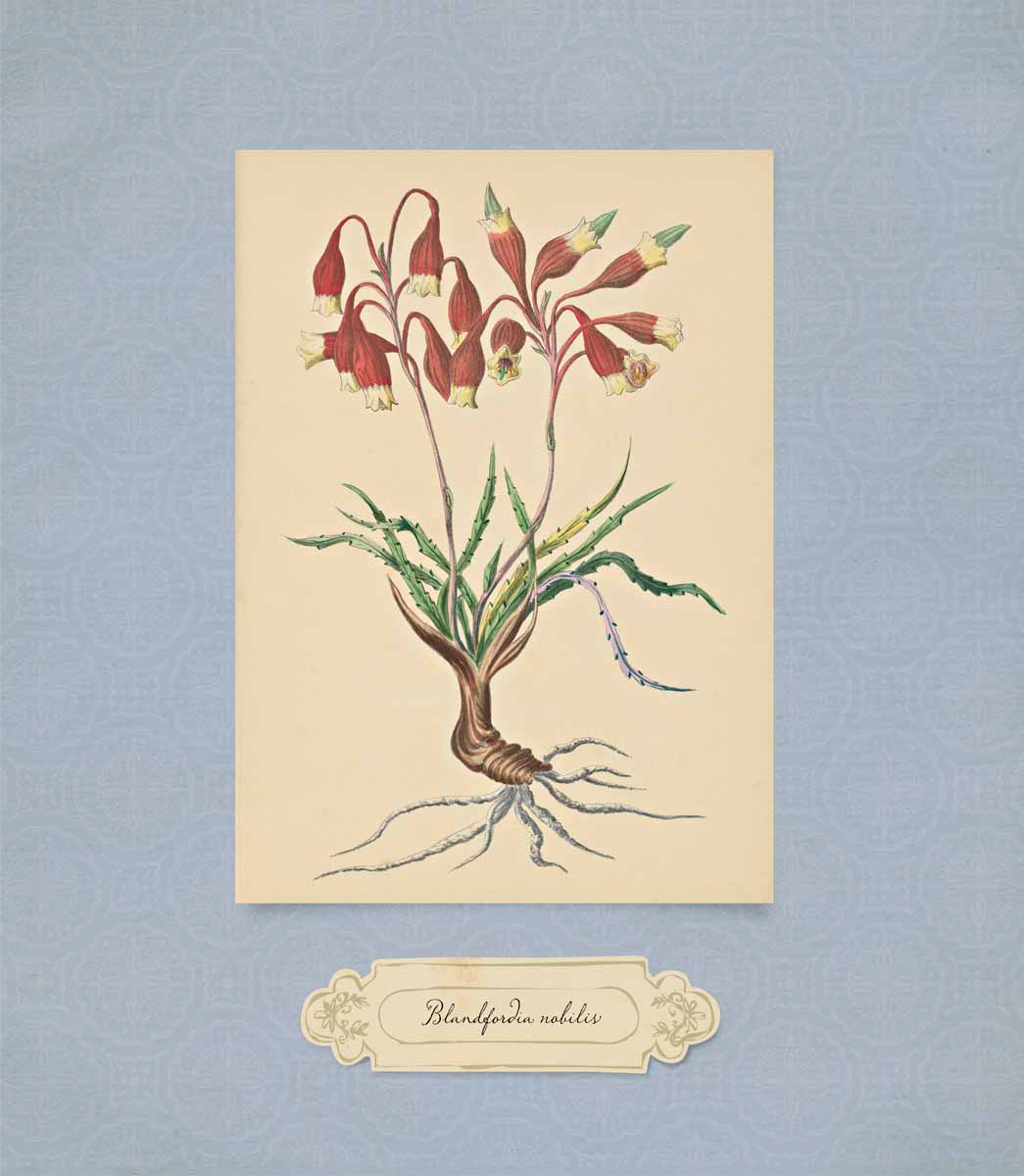

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Blandfordia nobilis 1887

The GENIAL FLORAL artist

Anna Frances Walker 1830–1913

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Blandfordia nobilis 1887

IN AUGUST 1881 ANNA FRANCES WALKER, KNOWN AS ANNIE, CONTACTED FERDINAND von Mueller to seek advice on a publisher for her folio of botanical illustrations. He recommended that she try Robertsons, a big business with offices in Sydney and Melbourne, or Mr Mullens, a Collins Street, Melbourne, bookseller:

As he keeps the most fashionable circulating Library, Carriages of the leading Ladies of Melbourne are at his door daily. Thus your work will come under the notice of the very people, who would like to have it on their drawing room table.

If Walker’s goal was botanical rather than decorative, she might have taken Mueller’s reaction as condescending. However, Mueller ended his reply with a generous offer. He would be willing to ‘contribute some notes to your text’ and she could use his name as a referee.

Walker took Mueller at his word. She travelled to Melbourne, taking her work with her and staying with ‘mutual friends’ in Brighton who ‘took me once a week to Baron Sir Ferd. von Mueller’. Mueller, she prattled:

received me very graciously—& gave up two hours of his valuable time—to look through & write the latest style of names—and to my astonishment he expressed himself delighted with all he saw & said he would not pass over one page—for it was the best & finest collection he had ever seen—& the Flowers were so accurately done, that there could be no mistaking what they were intended to represent & who taught me to class the Flowers of the River banks? The Flowers of the Plains? and those of the Forest? the foot of the Mountains, & those that grow on the Mountains? He said at length let me write what I think, for you deserve any praise that I can bestow—don’t let your Flowers go out of the country—take them to Sydney.

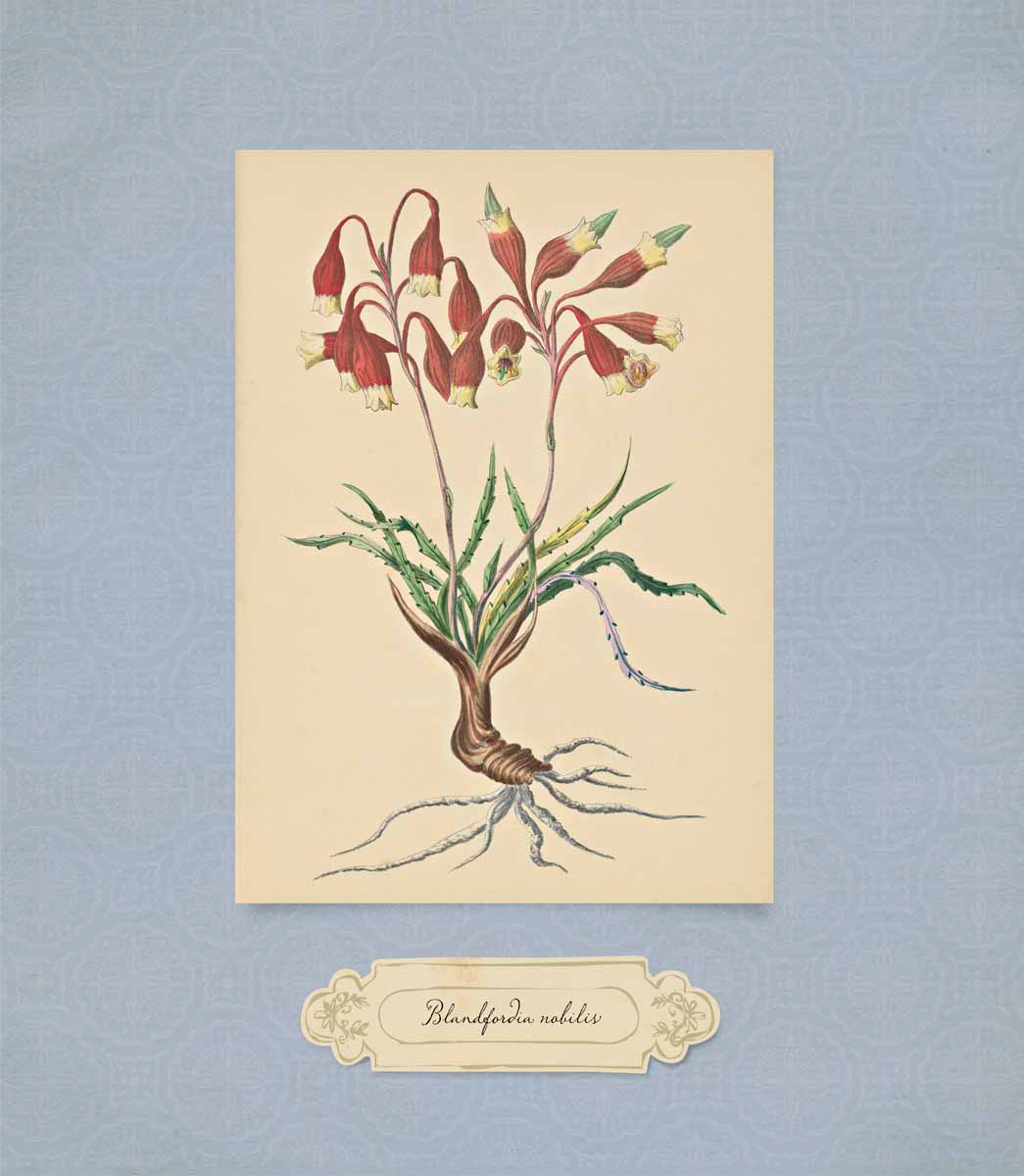

When Walker contacted Mueller with a view to publishing her collection of paintings of wildflowers, trees, grasses, ferns and fungi, she was 51 years of age. She was born in June 1830 at Rhodes, the family home on the Parramatta River at Concord, New South Wales, the fifth of the 13 children of Thomas Walker and Anna Elizabeth Blaxland.

Annie’s father had the important position of deputy assistant Commissary General in charge of the stores at Parramatta and Port Jackson (Sydney). As a high-ranking government official and free immigrant, he mixed with high society whose social round included balls, parties and dinners. This exclusive group included John Blaxland, the brother of explorer Gregory Blaxland who gained fame as being in the first European party to cross the Blue Mountains. The Blaxlands were at the centre of society in the early days at Port Jackson. Walker’s mother was one of John Blaxland’s six blonde, blue-eyed daughters who were much admired in the colony where men outnumbered women four to one. Wildflower enthusiasts who picked and pressed flowers, the girls became renowned as ‘the Roses of Botany Bay’ and the ‘lovely Botanical Flowers of Australia’.

Walker’s parents married in 1823, and in 1832 took their young family to live in Van Diemen's Land, on the South Esk River near Longford, where Thomas Walker had another property, also called Rhodes after his family estate in Yorkshire. In 1841, when Anna Frances Walker was not yet 11, her mother hired a governess to school the girls. She placed an advertisement in the Hobart Courier:

GOVERNESS WANTED. Required, a Lady capable of teaching the usual accomplishments in female education to pupils from four to sixteen years of age. Respectable references will be required; also the terms and particulars of qualifications, to be addressed, post paid, to Mrs. Thomas Walker, Rhodes.

Portrait of Anna Frances Walker 1860s

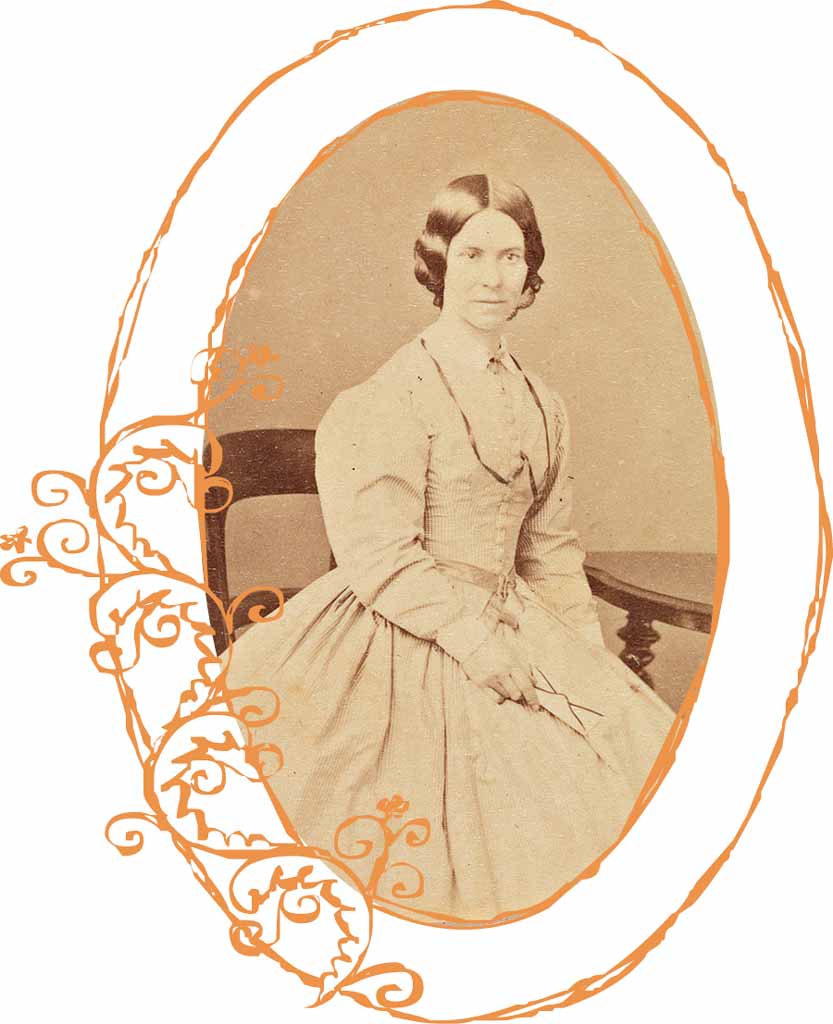

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, The Pink Eucalyptus of New South Wales

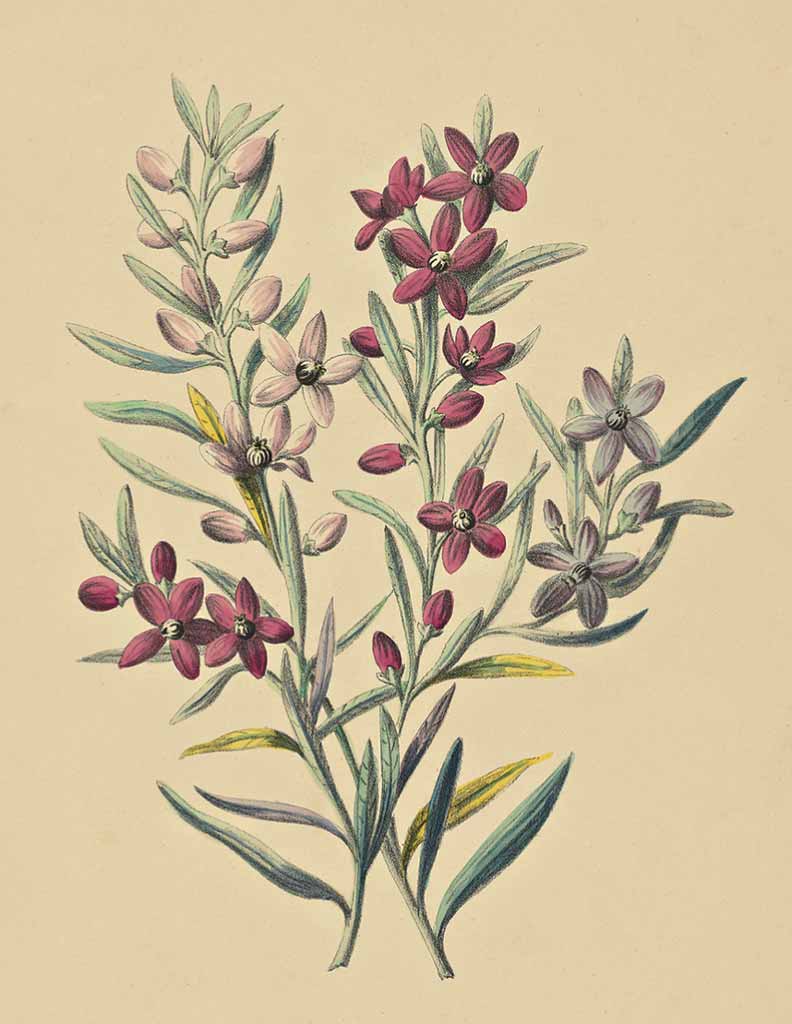

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Bunch of Wildflowers 1879

Walker inherited her mother’s interest in botany and botanical illustration. When she was about 16 or 17, she spent two years living with her grandmother at Newington, the Blaxland family’s home on the Parramatta River. Her grandmother further encouraged an interest in nature in her grandchildren, taking them on walks in the bush. The girls would collect, draw and preserve flowers and plants while the boys shot and stuffed birds. At Newington Walker received instruction in watercolour painting from Henry Curzon Allport, once a pupil of John Glover and a ‘wise old drawing master … the best to be had in Sydney’. She later remembered of Allport:

the Breakfast room was … given up for our use and such pleasant mornings they were for 2 hours. He was also a delightful companion, having such a good library of his own.

Thomas Walker died in 1861, and in 1870 the family returned permanently to Rhodes in Concord. The youngest girl eventually married, but Annie remained there with her two unmarried sisters for the rest of her life. She did not venture far, painting plants growing in the estates of Newington on the banks of the Parramatta River. Although Annie concentrated on painting Australian plants, she considered it ‘so homely to have old English flowers’. At Concord the extensive garden had poppies, foxgloves, hollyhocks, presentation lilies, hawthorn and lilac among other ‘English’ plants, which their gardener obtained from Charles Moore, Director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens, or by sending to the ‘Old World’ for seeds and bulbs.

A few years after the family’s return to New South Wales, Walker appears to have begun exhibiting her artwork. In 1873 she submitted ten wildflower works to the New South Wales Academy of Art exhibition, which went on to be displayed at the Agricultural Society’s show. That same year she won a gold medal in the London International Exhibition for her watercolours of Tasmanian flowers.

She continued to have some success with her flower paintings, gaining a Certificate of Merit in the 1876 Academy of Arts show. When the International Exhibition was held in Sydney in 1879, Walker entered several sections. Her collection of wildflower paintings garnered her a Highly Commended, the judges commenting that ‘such a large collection was evidently better suited for an album than as pictures, but the delineations are faithful’. She also painted 15 panoramic views for an exhibition at the Ladies Court (where women exhibited their art and craft work), gaining a First Degree of Merit for them. With her sister, Marion, she received an honourable mention for an album of New Zealand ferns. Of two songs housed with the album, The Sydney Morning Herald wryly reported that they were ‘carefully locked in the case, and it would be difficult to speak of their musical merit’.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Gompholobium grandiflorum, Bauera rubioides 1887 (detail)

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Ceratopetalum gummiferum 1887

In 1880, the year before she sought advice from Mueller, Annie sent seven flower paintings to the Melbourne Exhibition, accompanied by a copy of her gold medal. The judges took the hint and awarded her first place in the New South Wales’ Ladies Court.

By 1887, having had no luck with publishers, Walker self-funded the publication of Flowers of New South Wales, a small collection of her many flower paintings, perhaps intending to add further volumes if the venture was successful. Prominent in the book is the seal of the London Annual Exhibition of Fine Arts and Industries and Inventions—her gold medallion.

Unfortunately, Walker’s print house, Turner and Henderson, let her down. The poor quality of the ten chromolithographs did not do justice to her paintings. Still, the reviewer for The Sydney Morning Herald strove to be positive:

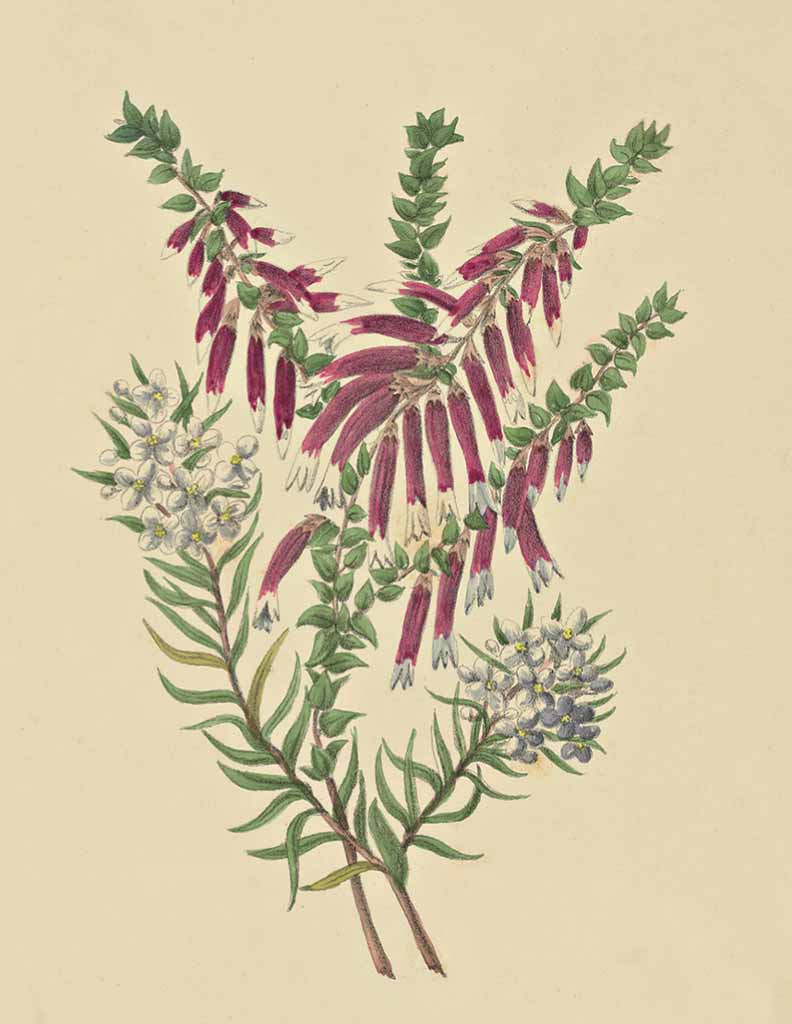

The drawings are admirable, and, whilst nature has been faithfully copied, the various subjects have been very artistically arranged. Amongst others there are the Christmas bush, the Mudgee wattle, the native fuchsia, Christmas Bells, the tea tree … as well as varieties possessing long and technical names. There appears to be correctness in every detail, excepting perhaps that the colouring is a little dull, and does not give a fair idea of the vivid brightness of the plants themselves.

The descriptions accompanying the plates demonstrate that Walker had an appreciation of the beauty and usefulness of nature but without deep botanical knowledge. One of the plants with the botanical name Melaleuca linariifolia, for example, she described as having ‘paper-like bark … its flowers have a strong perfume, and its leaves a delicious aromatic odour when bruised’.

Walker dedicated the book to her elderly mother and sent an inscribed copy to Mueller. Over the years she amassed eight volumes of botanical watercolours, some 1,700 illustrations, done in Tasmania and New South Wales between 1875 and 1910, which she hoped to publish. Part 16 is the ‘Plants Indigenous in the Neighbourhood of Sydney—Arranged According to the System of Baron von Mueller’. The part is ‘gratefully dedicated’ to Mueller and adorned with his pasted-in photo and a small, warm note in his looping hand: ‘To the genial floral Artist, Miss Ann Walker, with regardful remembrance from von Mueller’.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Melaleuca linariifolia 1887

In return, Walker paid her own rambling tribute to Mueller, who, she wrote:

looked through my extensive collection of the Flowers and Trees of North Tasmania, & New South Wales making additional remarks and corrections all through. He is the Botanist of the day, being covered with distinctions, & gifts, from all parts of Europe & has received the warmest of thanks from Italy, & other parts of the world, for the healthful, renowned Eucalyptus trees of Tasmania & Australia—the seeds of which were sent by him there.

Mueller employed a light editorial touch, correcting errors but not interfering with Walker’s text. Of the mistletoe Loranthus longiflorus (now Dendrophthoe vitellina) and its host she wrote:

A fine tree, a native of New South Wales, one of the few which shed their leaves in Australia [corrected by Mueller from ‘the only kind’] … with clusters of lilac blossoms, which make their appearance before the leaves, & have a very strong scent—The Native Mistletoe which grows on it forms a beautiful contrast to the lilac.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Eucalyptus—One of the Blood Wood Species

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Eriostemon silicifolius 1887

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Darwinia fascicularis, Ricinocarpus pinifolius 1887

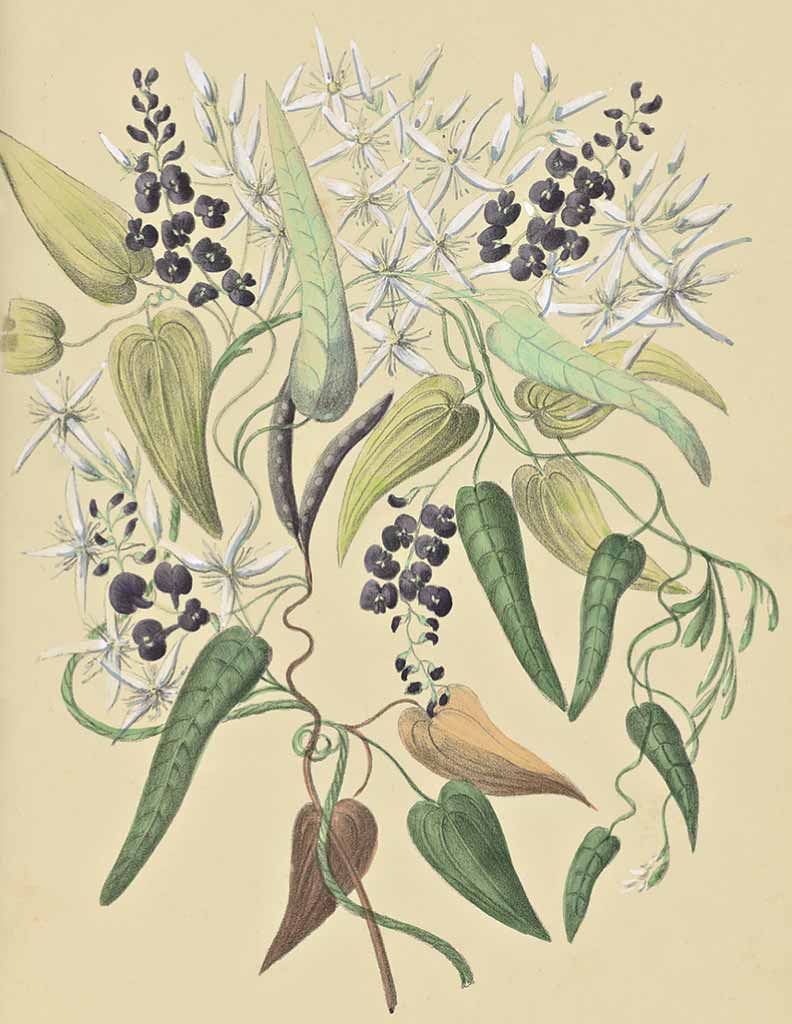

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Hardenbergia (Kennedya) monophylla, Clematis glycinoides 1887

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Epacris longiflora, Zieria laevigata 1887

Several pages of Part 16 of the sketchbooks are devoted to the story of Walker’s illustrative life and its frustrations, handwritten in April 1910 when she was almost 80. Also glued in are letters to her from Mueller, sent between 1890 and 1896.

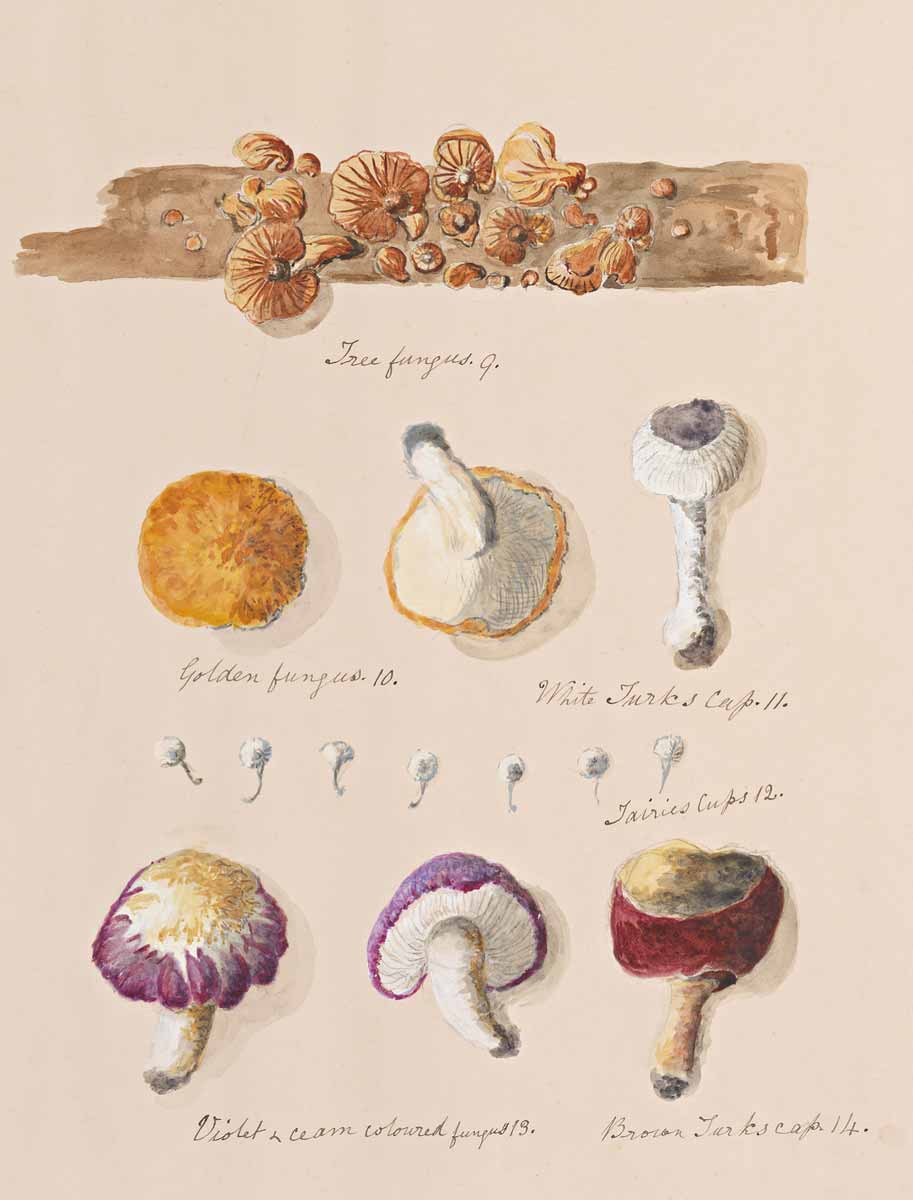

The letters revealed that in 1893 Walker began to sketch fungi on the family estate, sending the illustrations to Mueller via their mutual friends:

Some days ago, dear Miss Walker, our kind friends at Brighton brought your superb drawings of fungs … You deserve infinite credit for the talented zeal, with which you follow up these enquiries.

Mueller urged her to travel to the upper waters of the Bellinger River (on the mid-north coast of New South Wales) and ‘get the youngsters out with baskets to bring you all sorts of plants’. Thus, she might discover some new species.

Subsequent letters regarding fungi became a little strained as Walker failed to follow Mueller’s direction to number everything and send specimens as well as illustrations, so that identification was made easier. Uncharacteristically, he writes tersely in July 1894: ‘I thought I had expressed myself clearly, dear Miss Walker, in my long letter to your self as regards the safe arrival of the round box with fung specimens’. In March 1896, just six months before his death, probably responding to a demanding letter from her, he apologises:

I did not realise that I was in arrear[s] in naming plants for you, but during the last four years of extensive distress in this Colony my departmental engagements became so much augmented in the interest of breadwinning people that I could give but little attention to anything outside the Colony of Victoria although nothing would be more pleasing than to be useful to so enlightened a lady as yourself.

Evidently, Walker was still looking for a way to publish her groaning sketchbooks, for in 1895 Mueller advises her that the chromolithography could be done in Sydney. Three years later she exhibited her paintings for the last time, in London. The exhibition was organised and sponsored by the wealthy Miss Eadith Walker, a Parramatta resident but no relation, who attracted some criticism because she left the selection of artwork to several Sydney gentlemen with little artistic qualification.

The South Australian Register explained that Eadith Walker’s intention was to:

demonstrate to the art-loving world of England and that Continent that a distinctive national Australian school of art exists, and that its productions are sufficiently new and striking to be well worthy of study by connoisseurs.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Returned from Kew … 1894: Golden Shiner, White Shiner

It was hoped that the London picture lovers, who were considered to ‘comprise a numerous, cultivated, and thoughtful class of people’, would find the works acceptable. However, the reception was not as hoped:

several foolish attempts to damage the prospects of the Exhibition were made by writers of letters in the London Press who contended that it was absurd to pretend to represent the beauty of Australian landscape, considering that it had no beauty. It was asserted that Australian birds were without comeliness of form, brightness of colour, or melody in song, and that Australian flowers and foliage were alike destitute of grace.

Despite the colonial cringes on both sides of the world, several sales were made, but Annie Walker’s were not among them. She could not understand it as she considered herself among ‘the Pioneers of Fine Art’. She had hoped to find a patron; indeed, she ‘fully expected to receive another honour from His Majesty—I will always feel it to be the only, & greatest annoyance I ever had’.

These were not the only examples of Walker’s writings that reveal a naïve overestimation of the worth of her work. She was inordinately proud of her first award, at the 1873 London International Exhibition, writing in her 1910 remembrances: ‘I received from Prince Edward of Wales—now King of England … the first Gold Medal—that was given to an Australian lady; when 15 gentlemen each received one’. The Prince, she was told, had commented that her ‘Flowers were remarkable specimens’. In subsequent years, she continued, ‘I was often requested to send my Flower paintings to the Exhibitions of Colonial Art in England’.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Fungi

In 1887, the year her book came out and the Empire celebrated the jubilee of Queen Victoria, Walker took it upon herself to send Her Majesty, ‘the greatest Queen who sat on the throne’, several watercolours including one of a native rose, ‘her Badge of England’. Reportedly, the Queen ‘was much pleased’ with her gift with which Walker had enclosed her family tree as an assurance of her pure, that is non-convict, ancestry!

Buoyed by attention from British and botanical royalty, Walker’s expectations that her work would be publishable or saleable were high. Mueller, she recalled, had advised her:

don’t let your Flowers go out of the country—take them to Sydney where you ought to get £300 either from the University or the Parliament Buildings—or the Free Library.

Walker was remembering these words of encouragement in 1910 and by then some reality had set in. She ended the sentence, ‘but I did not’. After years spent trying to find a patron, and a less than successful self-funded publishing venture, she had given up and sold her extensive collection of eight volumes to Mr Mitchell (David Scott Mitchell, founder of the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and a cousin of the Scott sisters) for 70 pounds: ‘I let it go at the absurd price being too annoyed, & disheartened to trouble any more about the matter’.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Epacris microphylla, Sprengelia incarnata 1887

Walker’s remembrances are littered with her recollections of compliments from prominent men, including many from Mueller, ‘The Baron’. The Ward Coles, mutual friends in Brighton of both Mueller and Walker, apparently passed on his remark that her artwork was ‘the most truthful to Nature—whether magnified or otherwise & gracefully executed, & the Etchings so fit for vignettes’. George Ward Cole was a prominent Victorian with a strong interest in horticulture. His wife, Thomas Anne, was a sister-in-law of Georgiana McCrae who was at the centre of Melbourne’s artistic and scientific society. McCrae was herself a frustrated artist, wishing to earn a living from her paintings but discouraged from doing so by her family, including Thomas Anne, because of the stigma associated with a married woman earning a living. Quite possibly, Walker would have been introduced to McCrae during her stay at Brighton.

ANNA FRANCES WALKER, Bauera rubioides 1887 (detail)

Other eminent friends also encouraged Walker. Doctor James Cox and his ‘nice wife’, Walker wrote, were keen to see her work published. Cox, a leading Sydney physician, had a lifetime passion for natural history. He was a trustee of the Australian Museum, the first Secretary of the Entomological Society and, when it became the Linnean Society, its President for a time. Cox became a sort of patron and, Walker claimed, told her: ‘Miss Ford[e], Miss Scott & myself were the only one[s] who painted Wild flowers therefore we were the pioneers of Wild flower painting’.

No doubt Mueller, Cox and the others intended to be kind, but they had given Walker false hope. Cox was known for ‘his great kindness of heart, his hatred of anything mean, and his extreme care in avoiding any possible hurt to anyone’s feelings’. The benevolent Reverend William Woolls also assisted Walker with species identifications. Well-meaning friends and advisors, all influential, surrounded Walker, but her pretty works were just that. Mueller’s ‘genial floral artist’ says it all.

Walker’s artwork, as well as Mueller’s influence, must have been central to her life. She concludes her sketchbook autobiography: ‘Thus ends the sum of my life—Baron Sir Ferd. Von Mueller told me that I had spent 40 years of a happy innocent life’. Having recorded the accolades and annoyances, she ends on a cheerful note: ‘I am always happy when painting … as I find still some beautiful specimen that I have not seen in my daily walks’.