LOUISA ATKINSON, (1) D. atkinsoniana, (2) D. media, (3) Doodia aspera, (4) D. caudata

AN excellent CREATURE

Louisa Atkinson 1834–1872

LOUISA ATKINSON, (1) D. atkinsoniana, (2) D. media, (3) Doodia aspera, (4) D. caudata

IN 1865, 17 YEARS AFTER LUDWIG LEICHHARDT DISAPPEARED DURING HIS ATTEMPT TO cross the country from east to west, two trees blazed with an ‘L’ and a pair of old horses were found on the Flinders River in Queensland’s Gulf Country. It did not take much to convince Ferdinand von Mueller, Leichhardt’s fellow countryman and member of the Royal Society of Victoria, to take up the challenge. On the evening of 9 February, Mueller gave a public lecture on the fate of Leichhardt and the imperative for a renewed search for the missing party. There had already been several fruitless searches, but the general feeling was that: ‘It would be an eternal stigma on the history of Australia were this problem left unsolved.’

Mueller’s meeting took a novel turn when, as The Argus reported:

a generous supporter of the original Victorian expedition, the Rev. Joseph Docker, of Wangaratta, had gracefully suggested that to the tender benevolence of the ladies of our adopted land the call for the work before us should be assigned.

Mueller agreed and suggested that delegates for the ladies’ fundraising committee might be secured through the various churches.

In Sydney, naturalist, novelist and journalist Louisa Atkinson took up the call in her well-known ‘A Voice from the Country’, an intermittent series published in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Sydney Mail between 1860 and 1870. Her rousing appeal to the women of New South Wales suggested that Leichhardt:

may live—an old man, with white hair, with bent shoulders … He may have sunk to rest in the unknown wilderness. A mighty effort is making in Victoria to determine these doubts;—shall we not participate in so glorious and honourable a work? While the women of Victoria are collecting to fit out an expedition, shall their countrywomen here stand coldly aside? Surely not!

Mueller, meanwhile, had embraced the idea of a ladies’ cause beyond the norm. He was aware of the attraction to women of heroic explorers and excited by the ‘deep meaning, which this movement of Ladies undisputably possesses beyond its philanthropic tendency’. He hoped that the actions of the Victorian women would be an example to the ‘fair of other countries’. The movement, he opined to the Governor Sir Charles Darling, would prove:

for the first time in the worlds history, that Ladies may well step out of the circle which hitherto has ennarrowed their sphere of action in administrative functions for charity, that the exercise of their benignity need not be limited to the touching local displays which we have so long everywhere witnessed … great cosmopolitan enterprises of humanity may gloriously be realised under the care and unrestricted supervision of the Ladies.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Lehmannia nerifolia (now Bluebell Creeper, Sollya heterophylla )

The ladies raised the necessary funds but, through no fault of their own, the expedition ended in chaos and further loss of life.

Atkinson, though, was a lady who had already stepped beyond the local and was held up as an example to others. As Doctor (later Reverend) William Woolls wrote of her: ‘how suggestive her example is to the young ladies of the colony generally’. She was well known to Mueller as a discerning collector of plants having sent him hundreds of specimens, many via her friend Woolls. Some 120 of her observations were new and significant enough to warrant mention in English botanist George Bentham’s Flora Australiensis, the ambitious publication facilitated by Mueller. Of all his many collectors, Mueller urged Bentham, ‘Miss L. Atkinson has collected much in the Blue Mountains & is entitled to a special mark of honour’. In Mueller’s opinion, Woolls was the only other worthy of mention.

Caroline Louisa Calvert c. 1869

Indeed, in 1865, the year of the Leichhardt fiasco, Mueller had named for Atkinson not only a new species, Erechtites atkinsoniae, a herb she found in the Blue Mountains, but also a new genus, Atkinsonia ligustrina, a primitive mistletoe at first thought to be non-parasitic, which she discovered at Mt Tomah.

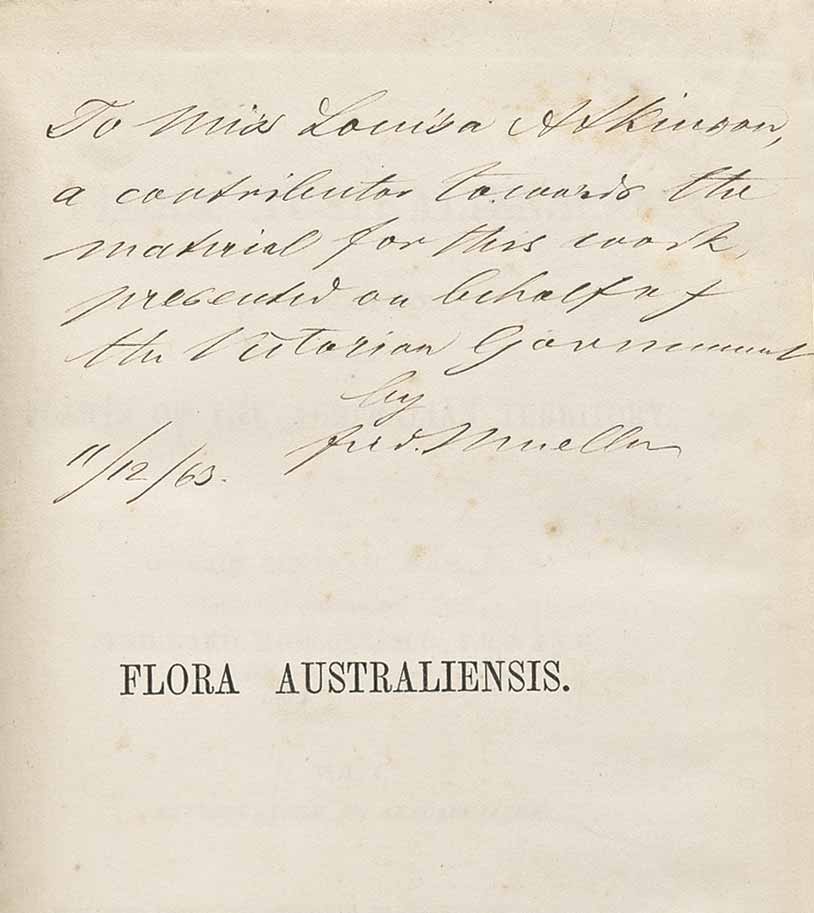

FERDINAND MUELLER, inscription for Louisa Atkinson, 1863

Having read her column and seen her illustrations in The Illustrated Sydney News in the late 1850s, amateur botanist Woolls had sought out Atkinson. Impressed by her personality, intelligence and keen interest in natural history, he introduced her to Mueller and other influential scientists such as William Sharp Macleay. For her part, Atkinson greatly valued her friendship with Woolls, referring to him as her ‘respected and esteemed friend “W.W.” of Parramatta, whose kind and amiable assistance in my botanical pursuits I feel much pleasure in acknowledging’.

Woolls was with Atkinson on the excursion to Mt Tomah early in 1861 when she discovered Louisa’s Mistletoe (Atkinsonia ligustrina), a root parasite not immediately recognised as a new genus, and Xanthosia atkinsoniana, a herb with pinkish flowers. Both were sent for identification to Mueller. As ‘L.A.’, Atkinson wrote about the outing in her ‘A Voice from the Country’ column:

After a while occurs a sandstone stratum, with an immediate and very striking alteration in the vegetation: the forest is thinner—the ironbark reappears—the undergrowth is flowery and varied; among others must be mentioned a Nuytsia [that is, Atkinsonia], of the Loranthus family, which is rendered very interesting from its attaining the proportions of a low shrub, and not being a parasite, as we usually find the Loranthus or Australian mistletoe; the blossom is yellow and crimson, and has a strong and rather sickly odour.

Atkinson sometimes referred to, but never boasted of, her botanical discoveries. In 1870, describing a trip to the abandoned Fitzroy iron mines some 12 kilometres from Berrima, she wrote, under the initials L.C. for her married name:

We soon lose sight of the town with its busy stir of life. The woods rise dark and thick, not devoid of interest to the botanical collector. On the tramway, tufts of Erechtites Atkinsonia, a Kurrajong old friend, were found. Specimens sent thence to Dr. Von Mueller were pronounced new to science, and named by that gentleman in compliment to the finder. It is probably a plant peculiar to mountain tracts.

By the time Atkinson married, her nature writing had matured to crisply expressive accounts of her country rambles that were full of information—a breath of fresh air beside the heavily scientific contributions to the broadsheets by her male colleagues. The fact that she had written four novels probably helped her find and refine her style. In her literary works, also, she was a coy author: her first novel, Gertrude the Emigrant: A Tale of Colonial Life published in Sydney in 1857, went under the pen name ‘an Australian lady’. The next, Cowanda, the Veteran’s Grant published in 1859, was ascribed to ‘the Author of Gertrude’. These were followed by Debatable Ground, or, the Carlillawarra Claimants (1861) and Myra (1864), both published as serials in the The Sydney Mail. Atkinson’s novels demonstrate that her experiences and observations of colonial society and human nature were as astute as those of the natural world.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Passiflora cinnabarina, Passiflora edulis, Passiflora subpeltata

Despite her reluctance to overtly claim authorship of her writings, Atkinson became well known, at least in New South Wales. The release of Gertrude, ‘this original Australian Tale’, was hailed as: ‘A remarkable event in the literary annals of this colony’. It was the first Australian-published book by an Australian-born woman. In a lecture on the country’s literature in 1864, the President of the Society of Arts in Sydney singled out Atkinson, reading passages from Gertrude and Cowanda and averring that:

Australia has not yet produced any novelists of note, if we except Miss Atkinson, who, to the credit of her sex and her country, has written and published two works of fiction of a highly moral character … The fair authoress has for some time been a resident of the Kurrajong, and from her mountain home at Fernhurst has contributed many sketches to the daily press, chiefly on subjects of botany and natural history sciences to which she is an ardent devotee, and in which she seems to have an able guide and compeer in Mr. Woolls, of Parramatta.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Chiloglottis diphylla

While Atkinson’s novels were well received, it is her natural history study and writing that is her most enduring legacy. In part thanks to the mentorship of Woolls, she was given access to the male scientific world and the emerging and diverging fields of botany, zoology and geology. She corresponded and discussed her finds and observations with leading scientists of the day. Although she attained a high level of botanical knowledge, she expressed her interest in a way that was acceptable for a woman of her times by sending her finds to experts and writing about them as part of local, nature-centred travelogues, not by naming plants and participating in scientific societies and publication.

Atkinson expressed her philosophy on nature writing in her very first article. With remarkable confidence for a 19-year-old woman, she wrote and illustrated an article on springtime in the bush and offered it to the editor of the new Illustrated Sydney News. It appeared in the second issue of the paper, on 15 October 1853, and began: ‘In these busy times, and in the universal pursuit of wealth which characterises the state of things amongst us, the beauties of nature are in danger of being overlooked’. Just as her novels had a religious and moral purpose, her aim in nature writing was to make the bush a comfortable place—somewhere to appreciate God’s work.

Atkinson was a populariser and recognised that terse descriptions and technical names did not help the cause:

It is a pity that so few of our native flowers have popular names: unless we study botany and recognise them by their Latin cognomen, they remain strangers … I purpose, therefore, giving the vulgar or familiar title—where one has been bestowed.

In her columns she expressed her concern for the excessive destruction of nature. For example, in 1871, writing of the runaway effect of clearing and its impact on ecological function, she observed:

in many localities miles of forest have died—apart from artificial means or ring barking—that the ultimate consequence will be of a nature materially to affect those districts there can be no doubt. The immediate effect is to render them marshy and unfit for sheep pasturage. It would seem that the forests have acted as safety valves.

Atkinson’s own health had never been good. She was so dainty and delicate that her great friend Woolls marvelled at how much she achieved:

Though frail as the tender plant that needs continual watching, her exertions in the path of virtue and science were surprising … [we] may well wonder, how on the elevated ranges, or in the depths of rocky gullies, she collected specimens of rare and beautiful plants.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Mayfly Orchid (Acianthus caudatus), Nodding Greenhood (Pterostylis nutans), Horned Orchid (Orthoceras strictum), Tartan Tongue Orchid (Cryptostylis erecta), Small Tongue Orchid (Cryptostylis leptochila), etc.

As well as her good works promoting nature, and her novels, Atkinson visited the poor and sick, wrote documents for the illiterate and ran a Sunday school for local children. She maintained warm, active friendships and was much loved for her ‘magnetic’ personality and kindness. She cared for sick and injured native animals and stuffed and mounted them if they died. She became an accomplished botanist, collecting and pressing specimens and sending unusual plants to Woolls and Mueller for identification.

Wherever she lived, as she had enjoyed doing with her mother, Atkinson planted a garden with English and native plants, particularly useful ones or those she wished to study. Gardens, she believed, were like nature, good for the soul:

Many a cottage wife has said to me ‘A bit of a garden’s such company’ and in that wholesome society she has escaped idling from house to house gossiping … I have seen a rough slab hut rendered quite an object of beauty, by having the common scarlet geranium trained against its walls: while a few saplings made into a rustic porch above an entrance, and clustered over with roses, turns a hovel into ‘quite a nice little place,’ in the eyes of passers-by, and to the residents strengthens home love, cheers and animates dull hours, and often keeps the husband and father away from the public-house; a better and happier man, as he cultivates a few flowers and vegetables.

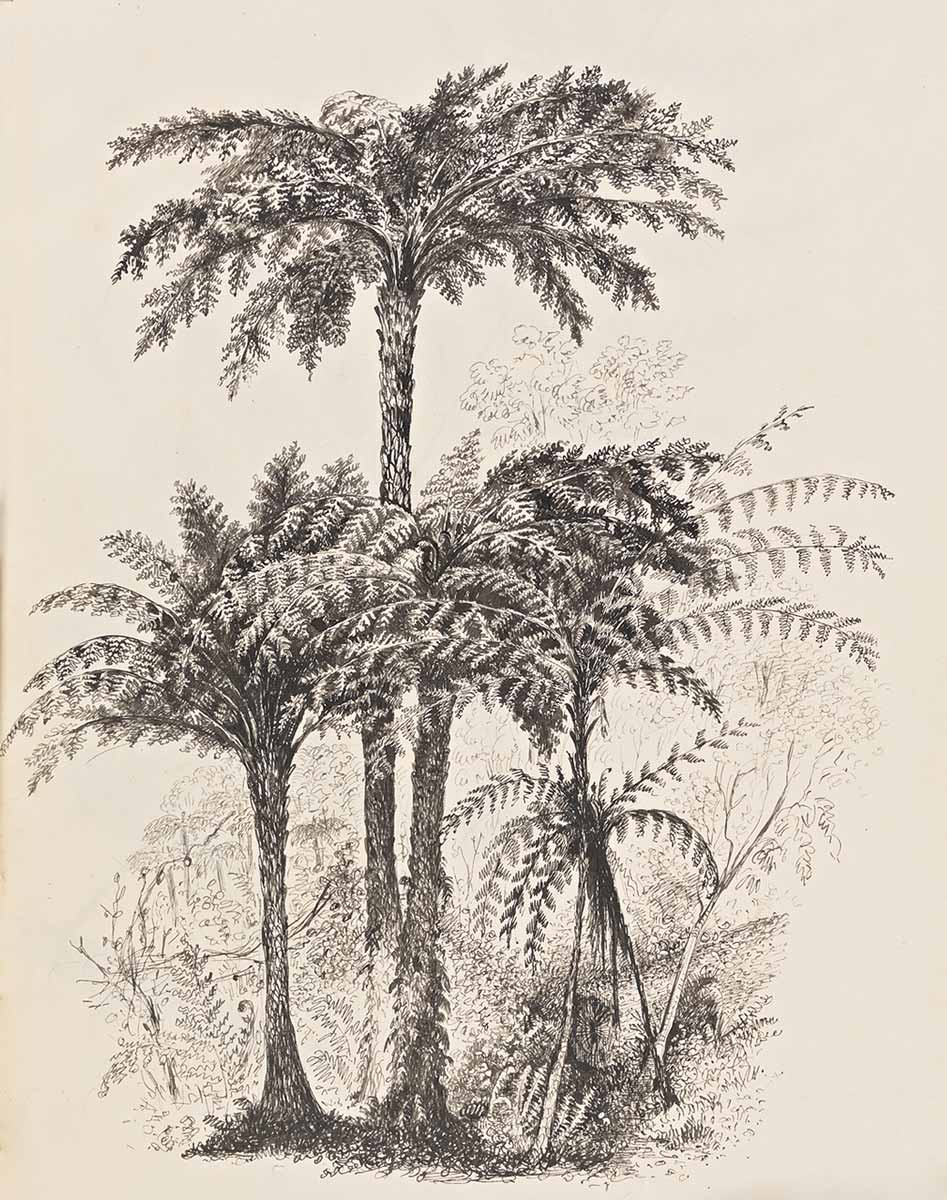

At Kurrajong, where their house was named Fernhurst, Atkinson established a little fernery. As she observed, there were ‘few who do not admire ferns’. A poorly studied group, ferns were popular additions to drawing rooms. Later, she began assembling botanical drawings and notes for a book on ferns, flowerless plants that she admired because they reminded her that ‘beauty when unadorned is adorned the most’.

Born Caroline Louisa Waring Atkinson, Louisa was the youngest of the four children of James Atkinson and Charlotte Waring. As he died in 1834, the year of her birth, she never knew her father, an innovative and respected grazier who published his agricultural ideas. Her mother was an extraordinary woman. A teacher, Charlotte wrote A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady, Long Resident in New South Wales (1841) which was the first book for children in Australia. After the death of her husband, Charlotte made a disastrous marriage to George Barton, the overseer of the family estate, Oldbury, at Sutton Forest, New South Wales. In 1839, she fled his violent, psychotic behaviour, taking her children with her. She spent many years battling the courts and trustees for custody of the children and control of the estate. Her independence and outspokenness were a shock to the chauvinistic legal establishment, yet she managed to keep the children and, after 20 years, finally won control of Oldbury.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Dicksonia antarctica, Alsophila cooperi, A. leichhardtiana, A. australis

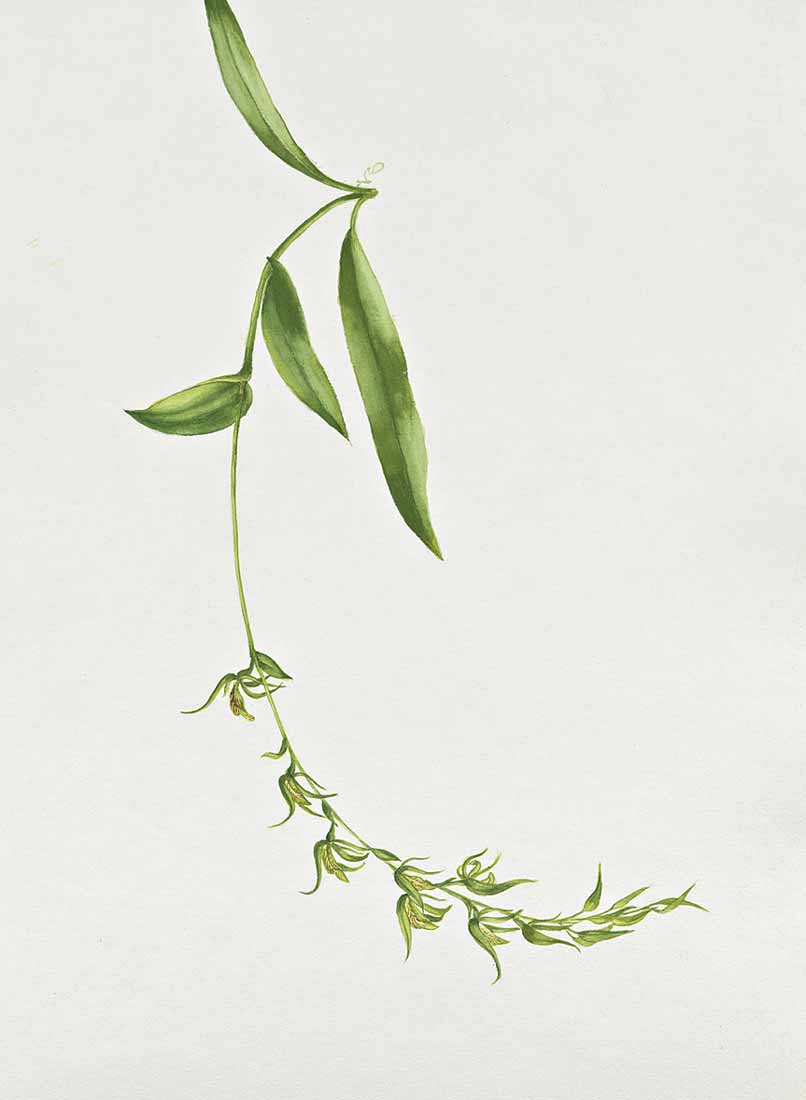

LOUISA ATKINSON, Lomaria discolor

Charlotte took the children first to the Shoalhaven then to Sydney before settling at Kurrajong Heights in the Blue Mountains, where it was hoped that the fresh clean air would be good for Louisa, her consumptive, weak-hearted fourth child.

Louisa had no formal schooling after the age of 12. Her ill health kept her at home and her novels, which have elements of autobiography, indicate that she may not have enjoyed the education on offer, which aimed to produce young ladies. Instead, she read voraciously and was taught by her mother who fostered her intense interest in writing, drawing and natural history.

At Kurrajong, as she grew up, Atkinson rambled on her shaggy little pony and began her scientific and charitable pursuits. There she met her closest friend, Emma Selkirk, the wife of a Richmond doctor, and together they went on collecting excursions, sometimes raising eyebrows by adopting more practical attire than was generally considered ladylike. Atkinson described her struggles with a more acceptable outfit in her Sydney Morning Herald column of August 1862. As she searched for a young Brachychiton plant for her garden:

A tall rank vegetation clothed the ground, among which, with riding habit looped up, I had been struggling, and when, panting and triumphant, the path was regained, a bristling incrustation of seeds of several plants which produce a species of burr presented themselves. Not only was every portion of the dress either sticky or prickly, but no shaking dislodged the intruders, while the fear presented itself that they would by degrees disengage themselves, tracking my path with ill weeds.

During her Kurrajong years, Atkinson also began her friendship with Woolls, who lived within riding distance, and his third wife Sarah Elizabeth who was closer to her in age. Doctor Woolls was bowled over by his knowledgeable new friend. Speaking on behalf of himself and Mueller in early 1861, he wrote in a botanical article for The Sydney Morning Herald:

I cannot conclude without expressing on behalf of Dr F. Mueller, as well as myself, the high sense I entertain of the untiring zeal of your correspondent in the Kurrajong, who has already furnished us with three hundred specimens of plants, many of which are exceedingly interesting. May a life, which has hitherto been devoted to the investigation of natural objects, be long preserved, and may a generous public afford every encouragement for the development of a native genius.

Atkinson’s life was not to be long, however. In about 1865 her mother Charlotte fell, breaking her arm and injuring her spine, leaving her a virtual invalid. They moved to Oldbury, then run by Atkinson’s brother, James John Oldbury Atkinson. Louisa’s natural history study was more or less curtailed as she nursed her mother and her own health declined. But she wrote a little, including her column plugging the Leichhardt Ladies Fund Committee.

By then she had probably met James Snowdon Calvert, a survivor of the Leichhardt expedition of 1844–1845 and, like Atkinson, a keen student of botany. On the ill-fated expedition, Calvert had been speared by Aboriginal people on Cape York and earlier nearly died from thirst and exhaustion but, with all but one of the party, he struggled into Port Essington and returned to Sydney a hero. Calvert promoted the need for a search for Leichhardt who never returned from his subsequent attempt to cross the continent. He was said to be an avid reader of Atkinson’s columns, and they may have met or become closer during the push for a new search for Leichhardt.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Platycerium alcicorne (probably Elkhorn Fern, Platycerium bifurcatum)

Possibly concerned about Louisa’s health, her mother cautioned against marriage but, after Charlotte died in 1867, the 35-year-old Atkinson decided to marry Calvert. They were wed at Oldbury in March 1869 and moved to Cavan station at Wee Jasper near Yass, which Calvert owned in partnership.

They were happy—‘Mr Calvert has as kind thoughtful ways as a woman and I want for nothing’, Atkinson assured their former maid, Mary Kelly—and some of Atkinson’s former energy returned. She took up writing nature columns again and collecting, sometimes exploring with her husband in a wagon drawn by two ponies. Of her new home on the Murrumbidgee, which for the plant-hunter offered new and exciting vegetation, she wrote enthusiastically about ‘the gleam and glitter of the rapid stream, where fish and ornithorynchus [platypus] and hydromys [water rat] are sporting’ and collected several ferns, one of which, Mueller informed her, was until then unknown for the area.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Traveller’s Grass, Arum Family (Settler’s Flax, Gymnostachys anceps)

LOUISA ATKINSON, Oldbury

ADAM FORSTER, Lyperanthus ellipticus 1925

MARRIANNE COLLINSON CAMPBELL, Epacris calvertiana, Sprengelia incarnata, Epacris microphylla 1873

Atkinson had not lost her eye for novelty and rarity. On 20 March 1871 Woolls wrote to her excitedly that she had rediscovered a crevice dwelling orchid that had not been seen for 70 years:

Your specimens arrived safely in Melbourne, and the Dr. says he will write to you. The orchid turns out to be Lyperanthus ellipticus which no one has found since the days of Caley!

In the 1870s Mueller would again pay tribute to Atkinson’s botanical prowess with yet more plant names: Pomaderris calvertiana, a Blue Mountains shrub; and, ‘in memory of a talented collector’, Epacris calvertiana, a streamside heath she collected at Berrima. Mueller also honoured Mr and Mrs Calvert with a strawflower, Helichrysum calvertianum.

The Calverts moved from Cavan to a cottage at Oldbury and then to a small farm at Winstead near Berrima. Calvert, encouraged by von Mueller, began breeding angora goats and Atkinson started on her sixth novel—Tressa’s Resolve—which was informed by Calvert’s experiences of the Gulf Country during the Leichhardt expedition. The pair continued to collect plants.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Fungi (detail)

In January 1871 Mueller was working on the sixth volume of Flora Australiensis and asked Atkinson to keep an eye out for rushes and sedges. He acknowledged some rushes she had already forwarded through their mutual friend:

dear madam, I got the select plants, which you kindly sent thro our good Mr Woolls to me, and of which I now furnish the names. Several give us new localities, and these will be quoted with the name of the accomplished finder.

As a postscript, Mueller updated her on the progress towards publication of a nature book of Australian plants and animals that she had illustrated, written and, with his assistance, sent to Germany to be engraved.

The war has upset almost all scientific work in Germany or at least brought it for a time to a stand still. So Prof Moebius [at Kiel, Mueller’s old university] tells me … But your fine drawing [s] are all safe and will probably be sent to Prof Krauss in Stuttgart (a special friend of mine) for the Royal Museum there, with a view to literary utilisation at the first favourable opportunity.

Atkinson passed on the news to Sarah Woolls:

Did I tell you that my Natural History has been removed from Kiel to Strasburg and placed in the Royal Museum there for publication. That is all I have heard of it for a long time since but if they are publishing the plates it will take a long time—and it may not be completed for a year.

For two short years the Calverts were a happy, well-respected, productive couple. He was described as a modest hero and she as his ‘amiable and highly cultured wife’. In mid-1871, 37-year-old Atkinson became pregnant and the following April gave birth to a daughter, Louise Snowden Annie. Tragically, Louisa died just 18 days later, suffering a heart attack, purportedly after her husband’s riderless horse returned to the homestead.

Louisa was buried in the Atkinson family vault at All Saints’ Church, Sutton Forest. Her friends and family were devastated. Calvert, earlier described by Leichhardt as a good-natured, talkative young man, ‘full of jokes and stories’ and with ‘a good stock of small talk’, sank into a deep depression, aged prematurely and withdrew from the world. Their daughter was left to a lonely childhood, especially after her uncle James died in 1885 and she was forced to leave Oldbury. Many of her mother’s collections and works are thought to have been burned at that time. Also, unfortunately, Atkinson’s natural history manuscript that Mueller sent to Germany was lost in the chaos of the Franco-Prussian war and only a few plates or copies of plates survive.

Woolls, by 1872 a reverend, praised Atkinson as ‘one of the most interesting of Australia’s daughters’ and ‘valued her friendship for the keenness of her observations and her skill in delineation’. He felt her loss long after her death: ‘I wish you had known Louisa Atkinson … she was an excellent creature, and worthy to be had in remembrance’, he wrote to botanist– engineer Henry Deane in 1886.

The Reverend penned a poem in tribute to Atkinson and her love of botanical pursuits. So too did a bereft Emma Selkirk, whose family’s nickname for Atkinson was Daniella, the diminutive of Diana, for the Goddess Diana, and the scientific name of a pretty plant that grew at Kurrajong. In Selkirk’s poem, she remembered her friend’s ‘fresh beauty and sweetness’ and passion for rambles in the bush:

Equipped for the chase it delights her to ramble Through wilds the rude footsteps of man never trod … Behold her returning, with sylvan spoils laden Of flower and insect and lichen and fern; Each creature that liveth is dear to this maiden, Who loves the great lessons of nature to learn. The hoarder of treasure, the votary of pleasure, May seek in the whirl of the city to dwell; But let me be roaming from morning to gloaming, Over mountain and valley with dear Danielle.

Calvert had a tablet erected in Sutton Forest Anglican Church inscribed: ‘Distinguished as a Botanist and Authoress, and well known for her charities to the poor’. Woolls was anxious that Atkinson be remembered and, with the help of Mueller and her other friends in the sciences, the press and the church, raised the funds for a marble plaque in St Peter’s Church, Richmond. He gave a sermon at its dedication on the second anniversary of her death. The obituary in The Sydney Morning Herald captured the anguish at her loss: ‘This excellent lady, who has been cut down like a flower in the midst of her days’.

LOUISA ATKINSON, Fungi (detail)