FANNY DE MOLE, Native Cotton (Gomphocarpus arborescens) and Unknown Species 1861

DRAWN with loving HANDS

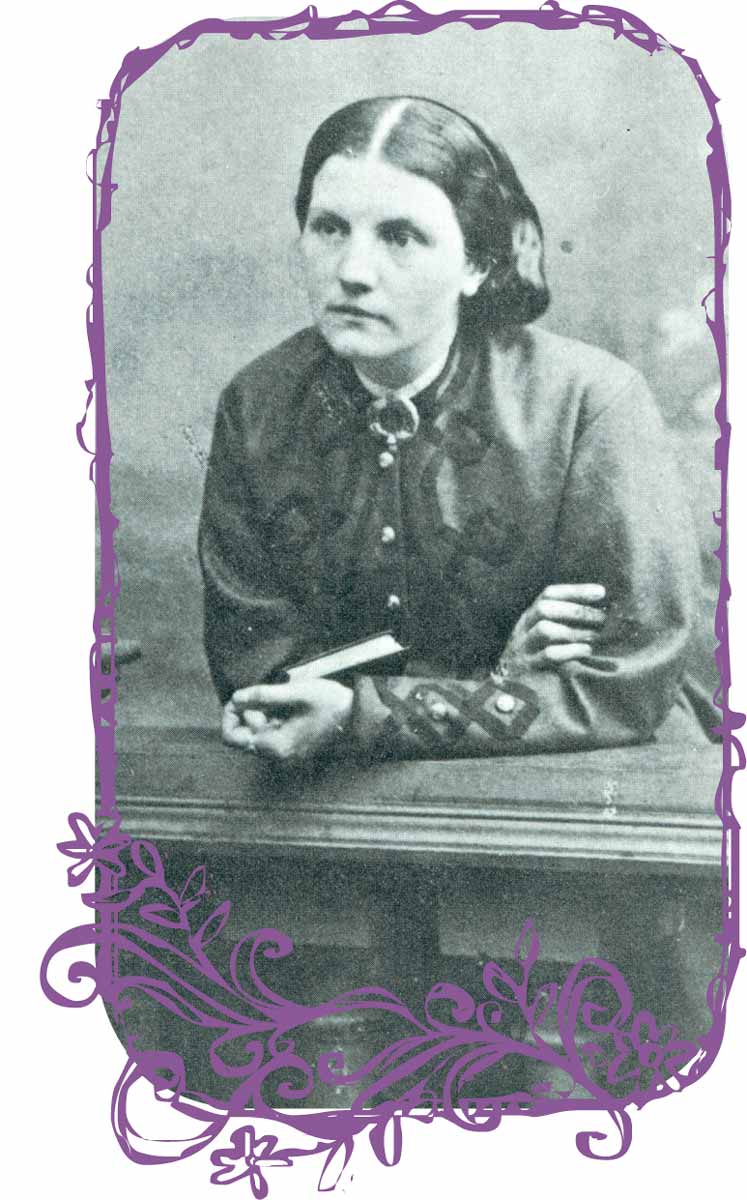

Fanny De Mole 1835–1866

FANNY DE MOLE, Native Cotton (Gomphocarpus arborescens) and Unknown Species 1861

FANNY ELIZABETH DE MOLE WAS THE FIRST OF THE CROP OF COLONIAL WOMEN TO bring colour to botanical publications on Australia. The women’s works promoted Australian plants to a British audience interested in their potential cultivation. They also gave reassurance that even in this far-flung corner of the Empire, though the familiar plants of childhood were missed, beauty was in abundance. So, too, was God in evidence. As De Mole asks in the preface to her sole publication, Wild Flowers of South Australia (1861):

May not these pictures, which show such new combinations of form and colour, serve, at least in those who see them for the first time, to stir afresh a feeling of love and gratitude to Him who manifests such an overflowing love towards us?

Not only was De Mole devout, she was also suitably modest, downplaying her talents as was de rigueur for women placing themselves in the public eye:

The present little work is offered, not as having any botanical pretensions, but simply as a Book of Flowers; flowers with which we daily meet in our own grounds and neighbourhood.

De Mole barely even claimed authorship of her ‘little work’ which came out under the discreet cover of only her initials, F.E.D. The original illustrations were shipped to England where they were transferred to lithographic stone and printed by Paul Jerrard and Sons of Fleet Street, known for their production of fine books ‘for the drawing room’. Back in Adelaide, the family hand-coloured the plates, the gilt borders may also have been added, and then the books were assembled and bound. No two copies are alike.

It has been speculated that De Mole’s sister, Harriet Jane, also a talented artist, contributed artwork to the book. However, it seems that Harriet was still developing her painterly skills at the time that the original paintings must have been completed (about 1859). The first appearance of both sisters in the exhibitions of the South Australian Society for the Arts was in 1866 when ‘Miss De Mole’ won the fruits and flowers section and ‘Miss H.J. De Mole’ won eighth prize for a figure of a boy, which the judges thought showed potential, even though the hands and feet were too small. Fanny De Mole died a few weeks after this exhibition. The next year, seemingly confusing the two sisters, a critic commented that Miss De Mole’s ‘pretty groups of flowers’, though they won prizes, were not ‘arranged with her usual judgement, or finished with her usual care’. By 1870, though, her sister Harriet’s floral artwork was being described as exquisite. Harriet’s last entries in the annual show seem to have been in 1872 when she donated her prize money to the orphans’ home.

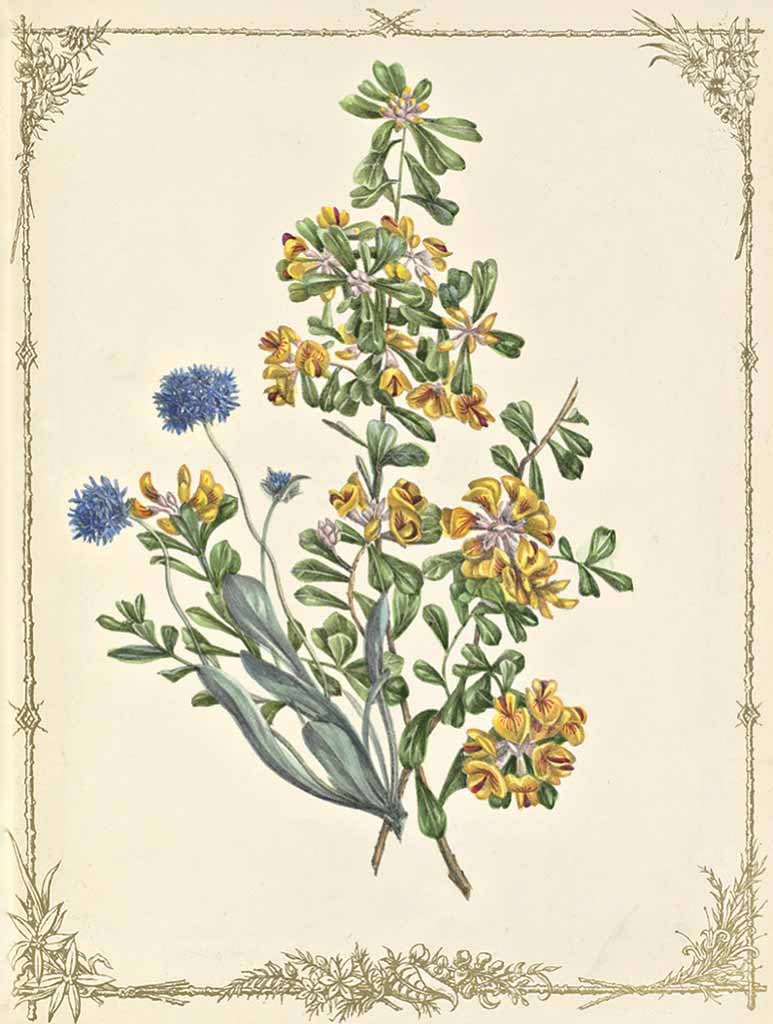

FANNY DE MOLE Hardenbergia-ovata (Lilac) 1861

The 20 plates of Wild Flowers of South Australia illustrate 39 species and the title page adds another, the river red gum. The accompanying text provides a brief description of each plant, its distribution and usefulness. Of Hardenbergia, known locally as lilac, De Mole wrote:

This is a climbing plant, and is often seen over cottage verandahs and trunks of trees; and may, by a careful use of the knife at the right season, be kept in the form of a garden shrub; and it is even used for hedges.

She described the native myrtle as ‘highly ornamental in our gardens’ and commented that its ‘delicate tints and fragrance make it a great favourite’. The bark of the silver wattle, she noted, was useful for tanning.

De Mole made no claim to scientific intent, yet in giving information on the plants in nature and attempting to name them scientifically according to order, genus and species, she was dabbling in the young discipline of botany. How she arrived at these classifications is not known, though she and her family were well read. If they were aided in their identifications, it seems likely De Mole would have acknowledged that assistance. Instead, she simply refers to work pending:

The botanical information on Australian plants is very scanty, but we are promised a work by Dr Müller, which will supply the need beginning to be so much felt by the scientific who are interested in this country.

Fanny Elizabeth De Mole, a Photograph Taken in 1865, the Year before Her Death

Given his normal willingness to name plants collected or illustrated, it is tempting to think that Mueller assisted. The alternatives, however, seem much more likely. The De Moles lived in Burnside and among their neighbours was Frederick George Waterhouse, the first curator of the South Australian Museum and a collector of flora and fauna. The family would also have known George William Francis, who in 1854 became the first superintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Adelaide. Certainly, they would have strolled in the budding Gardens—40 hectares on the River Torrens in central Adelaide that Francis very quickly fenced to keep out livestock. He began planting, laid out a central walk which allowed for crisscrossing streams, and installed paths and seating. Francis was developing the Gardens ‘for the education of all colonists’, a philosophy to which Mueller also subscribed, and to this end he gathered scientific books for a library open to visitors to the Gardens.

Francis had been lobbying for the establishment of a botanical garden since his arrival from England in 1849. He probably met the young Mueller before the botanist left South Australia for Victoria in 1852 and they were in contact until Francis retired as Director in 1865, a couple of days before his death. They also traded plants and seeds and Francis sent newly discovered specimens to Mueller for identification.

De Mole would have added to her knowledge of plants by reading the newspapers, which often reported on botanical items of interest. The first documented use of the name ‘Sturt Pea’, now popularly known Sturt’s Desert Pea, is thought to have been in a letter to the editor of The South Australian Register 19 July 1858 inquiring about planting times for Adelaide. Until then it had been known variously as ‘Beautiful’ or ‘Showy Donia’ and ‘Dampier’s Clianthus’ among other epithets. It was cultivated and much admired in 1850s Adelaide. The South Australian Advertiser of 28 February 1859, for example, announces that a bunch of ‘Sturt’s Pea’ entered by a Mr Treloar won the 10 shilling prize for the best collection of cut flowers at the second Northern Agricultural Society exhibition held in Adelaide.

De Mole’s ‘Sturt Pea’ (‘Sturt’s Pea’ in her text) was one of the three species she illustrated that did not occur naturally around her home.

Most of the flowers De Mole drew could have been collected growing wild around The Waldrons, Burnside, where the family lived. Certainly, years later, her niece Violet De Mole recollected of the book: ‘Specimens from the jungle, as they called the scrub, were painted by my aunt Fanny Elizabeth de Mole’. One of Fanny’s older brothers, Henry De Mole, purchased the property in 1854 and built a stone cottage for the family. After a few years they established a large two-storey bluestone house with verandahs and a beautiful garden containing a large orangery. The property was surrounded by a wall of stones that had been dug from the soil by their gardener, Irish horticulturist William Reddan. Reddan later became caretaker of the Naracoorte Caves where he established the famed gardens with grottos and rockeries that became a part of the huge fad for cave gardens and tours.

FANNY DE MOLE, Sturt Pea (Clianthus dampierii) 1861 (detail)

FANNY DE MOLE, Calythrix scaben, Anthrocercis littorea 1861

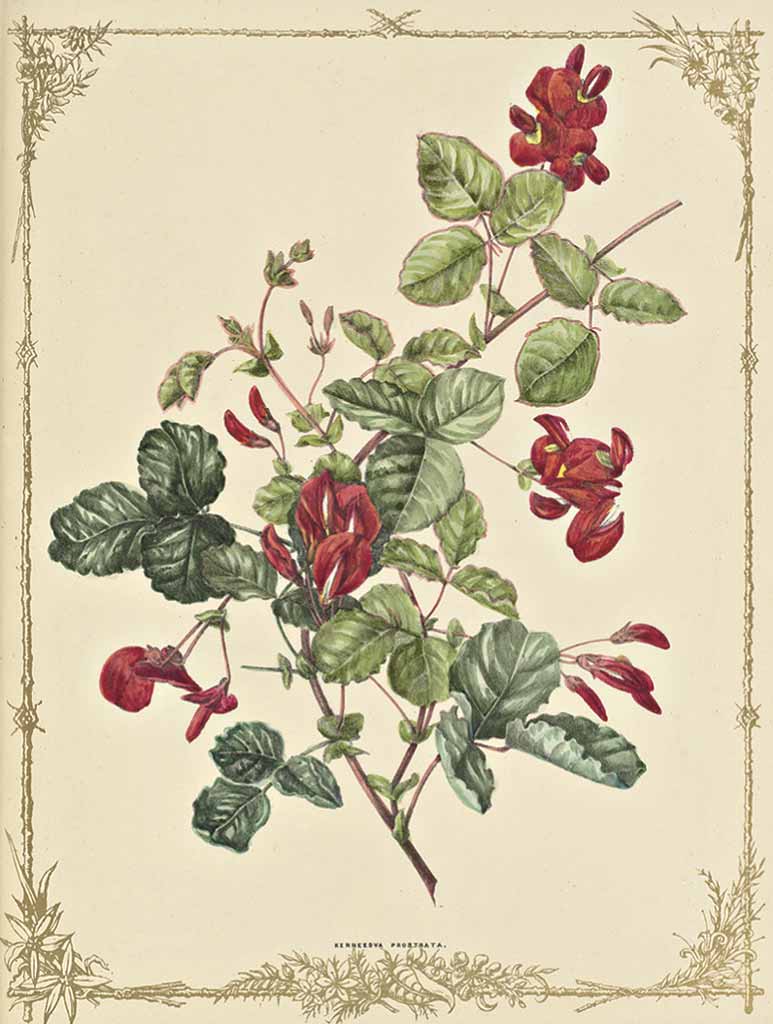

FANNY DE MOLE, Kennedya prostrata 1861

FANNY DE MOLE, Pultenea daphneoides, Brunonia sp. 1861

FANNY DE MOLE, Orchis—Myrtle (Thelgmitra ixioides, Myoporum cunninghamei) 1861

FANNY DE MOLE, Parasitical Plants (Loranthus cassuarinae, Loranthus eucalyptoides) 1861

From The Waldrons, soon after arriving in Australia, De Mole wrote lovingly to her uncle in Sydney of the portfolio that was to become the basis of her book:

These are copies of some of the wild flowers of our new home. They do not perhaps exceed in beauty those of dear old England but their novelty may make them interesting; and the fact that they were drawn with loving hands will make them please you … I hope from time to time to add some more, the better to fill the little portfolio, but these are all I have as yet accomplished.

FANNY DE MOLE, Westringia rosmarinifolius 1861 (detail)

Australia gave De Mole a new lease on life. Despite being confined to a wheelchair and the couch in England, in sunny Adelaide, as Harriet wrote of Fanny: ‘I am glad to say my sister had so far improved in health as to be able to take a little exercise on horseback’. She was also able to walk around, her brother George wrote in his unpublished autobiography.

Starting in 1863, Fanny won prizes in every annual exhibition by the Society for the Arts—usually for watercolours of flowers but also for chalk or crayon drawings. At the society’s first exhibition, a copy of Wild Flowers of South Australia, valued at six guineas and donated by the Bishop of Adelaide, had been given as the prize for the most meritorious drawing by a pupil of the South Australian School of Design. Perhaps interest in the book gave the demure De Mole the confidence to try her hand in these events.

De Mole’s mother was Isabel, Mrs John Bamber De Mole, who arrived with Fanny and her three youngest siblings—George Edward, Harriet and Ernest—in February 1856 after a ‘tedious’ four-month voyage on the Albermarle from Gravesend in Kent. The pious, cultured family had lived in Clerk’s apartments at Merchant Taylors Hall, London, seat of the charitable organisation of the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors. Two of the De Moles’ young children had died from tuberculosis and in 1845 the disease claimed the family’s patriarch, a solicitor. A few years later Isabel moved the family from the polluted air, poor sanitation and cold climate of a big English city to more rural locations before George, a midshipman in the Merchant Navy who had visited and liked the young city of Adelaide, helped his mother and siblings to emigrate. The eldest son, solicitor John, had already sailed with his wife for New Zealand. Henry had withdrawn from his degree at Oxford University and with Frederick arrived in Adelaide in 1853. Henry sailed for New Zealand almost immediately to bring his ailing brother to South Australia, but John died when they reached Sydney.

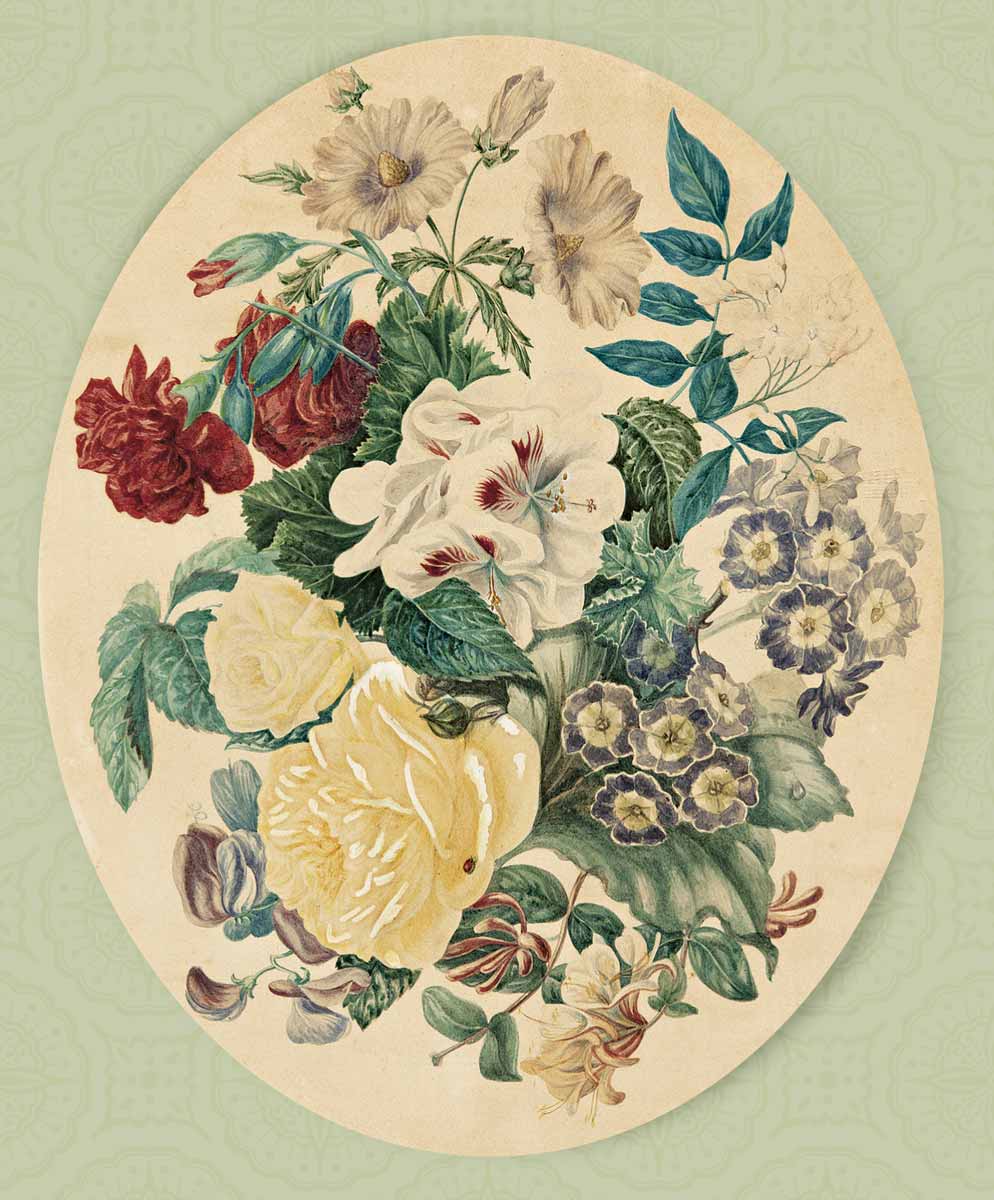

FANNY DE MOLE, Flower Study c. 1860

The remaining sibling, Emilie, had gone with her husband, the Reverend John Stuart Jackson, to another corner of the Empire, the historic city of Delhi in northern India where the Reverend joined the Christian mission of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. In 1857 a revolt against the British initially met with some success but was eventually suppressed, though not before a bloodbath during which Christians were particularly targetted. That year Jackson left ‘so that his wife might escape the horrors of the mutiny’. In Adelaide he became the second rector of St Bartholomew’s at Norwood. Emilie gave birth to a daughter in March 1859 and died a month later, aged 27. Brother Frederick had died the August before, aged 30. Tuberculosis had devastated the family, something Mueller would well have understood. In the space of three decades, De Mole’s mother had suffered the premature deaths of her husband and six of her children. In December 1870 The South Australian Register reported the 78-year-old’s death with the quaint turn of phrase: ‘Isabel, relict of the late John B. De Mole’.

In the summer before her own death, Fanny had been well enough to travel to Melbourne by ship, presumably to visit her brother Henry who had settled there in 1857 and had become a successful banker and later a magistrate. She returned on 29 January on the Aldinga. The most fragile of the surviving family, she made it to her thirty-first birthday, passing away at The Waldrons on Boxing Day 1866. Thanks to the healthier living conditions of Adelaide, she had lived longer than all her consumptive siblings. With her death, the hold of tuberculosis on the family was finally broken.

The move to Australia had also proved worthwhile for her four surviving siblings, three of whom went on to raise their own families. Harriet, De Mole’s only surviving sister, with her brother Ernest and his wife, returned to London in 1875. There Harriet may have joined the Sisters of the Church, described as: ‘sisters of rare gifts, selected as they volunteer their services to promote the work of God, because of their personal merit … highly accomplished, zealous and pious’.

Amidst so much family tragedy there were also highlights. Apparently, 1861 was a good year: Reverend Jackson assisted in the marriage of George at St Matthew’s, Kensington, and Fanny’s beautiful book was published. She dedicated the work to Augustus Short, the first Anglican bishop of Adelaide, and donated the proceeds of sales to the churches that were under construction for ‘the highest interests of our fellow colonists’. The title page depicts St Michael’s Church, Mitcham, with its slate roof and balcony. Outside the churchyard fence stand two well-clothed local Aboriginal people with spears, beside them iconic Australian plants—a grasstree and eucalypts. Scrutinised today, such images would not be considered acceptable, but De Mole’s intention was noble. Fanny De Mole and other Adelaide members of the family are buried at St Matthew’s, one of the churches she hoped to fund. As a grateful parishioner wrote in 1891: ‘Wild Flowers of South Australia will never allow her memory to fade’.

FANNY DE MOLE, Lupin—Flax (Lotus australis, Linum gracile) 1861

FANNY DE MOLE, Gum Wattle—Silver Wattle (Acacia cunninghamei, Acacia longifolia, Corymbosia sp.) 1861