ROSA FIVEASH, Xanthorrhoea semiplana (Grass Tree) c. 1890

More OR LESS LADIES

Rosa Fiveash 1854–1938

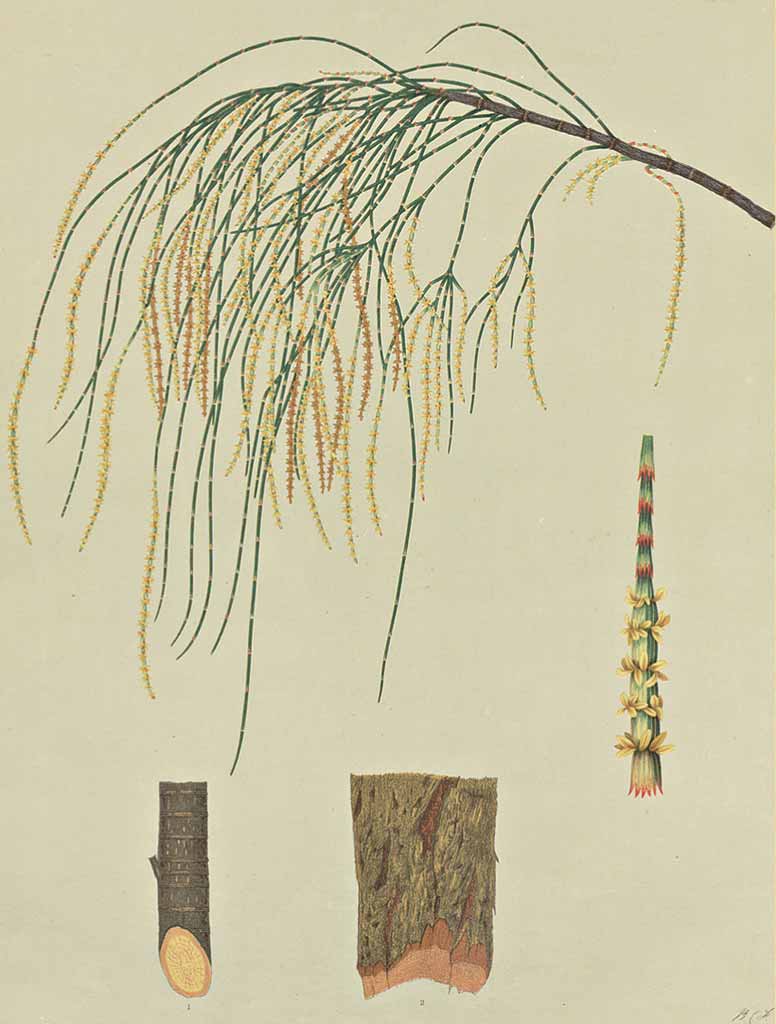

ROSA FIVEASH, Xanthorrhoea semiplana (Grass Tree) c. 1890

FORTY YEARS AFTER THE DEATH OF FERDINAND VON MUELLER, DOCTOR RICHARD Sanders Rogers told an interviewer for the Adelaide Advertiser that as a medical student at Adelaide University in the early 1880s ‘his love for botany developed under Professor Ralph Tate and Baron von Mueller’. His acknowledgement of Mueller was in part because of the botanist’s pioneering work on Australian botany and his prolific writings, but he also knew Mueller personally: ‘Every now and then he would come across, and we used to go on botanical excursions all over the Adelaide hills, and cover a great amount of ground’. Nonetheless, Mueller rarely made the journey to Adelaide.

Whether Rogers’ long-time associate, botanical artist Rosa Catherine Fiveash, ever met Mueller is uncertain. Her collaboration with Rogers started in the twentieth century, but Fiveash had earlier worked with John Ednie Brown on his publication The Forest Flora of South Australia and Brown was also a Mueller associate. Mueller supported Brown’s work as the colony’s conservator of forests, referring in 1879 to the newly appointed Brown’s ‘excellent work’. At the very least, Mueller would have been aware of Fiveash’s contribution to Brown’s book—her first foray into illustration for publication.

The government had lured Scottish-born Brown, a rising star in scientific circles, to South Australia. His first report was a thorough assessment of the state of the colony’s forests and their possibilities and he was bitterly disappointed when its recommendations were not adopted. Tension continued, particularly with the Chairman of the Forest Board, even though Brown was widely touted as ‘about the most competent man in dealing with forestry in all the Australian colonies’. In 1890 Brown received a better offer from the Premier of New South Wales where policy was more to his liking—there vast reserves had been set aside to ensure forests were sustained. Offered the position of Director-General of Forests with a higher salary, travel allowance and free house, Brown quit South Australia. He was denied copyright of his book, the South Australian Commissioner of Crown Lands claiming the multivolume work would be continued—but it was, in fact, abandoned.

H. BARRETT, title page of The Forest Flora of South Australia 1882

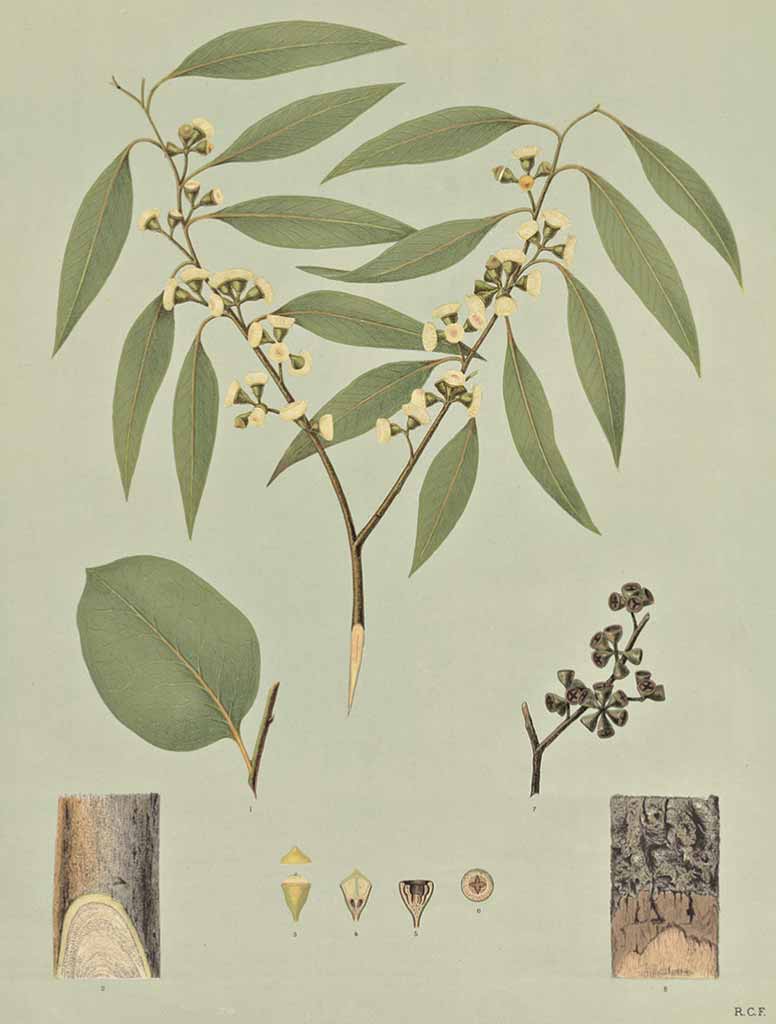

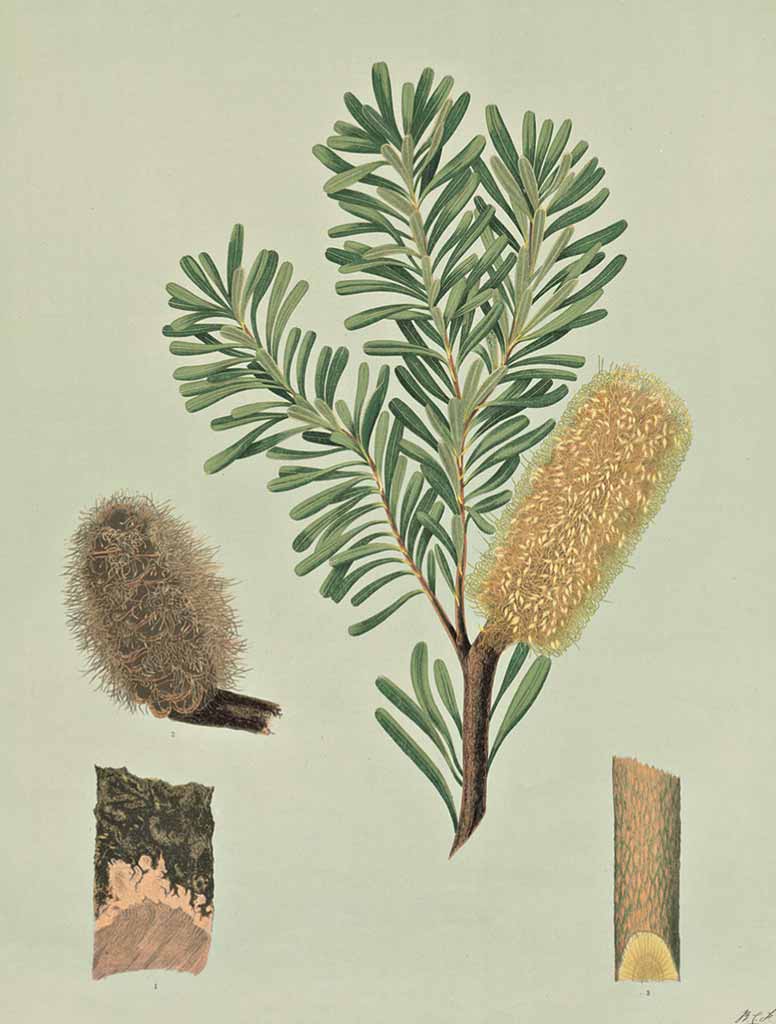

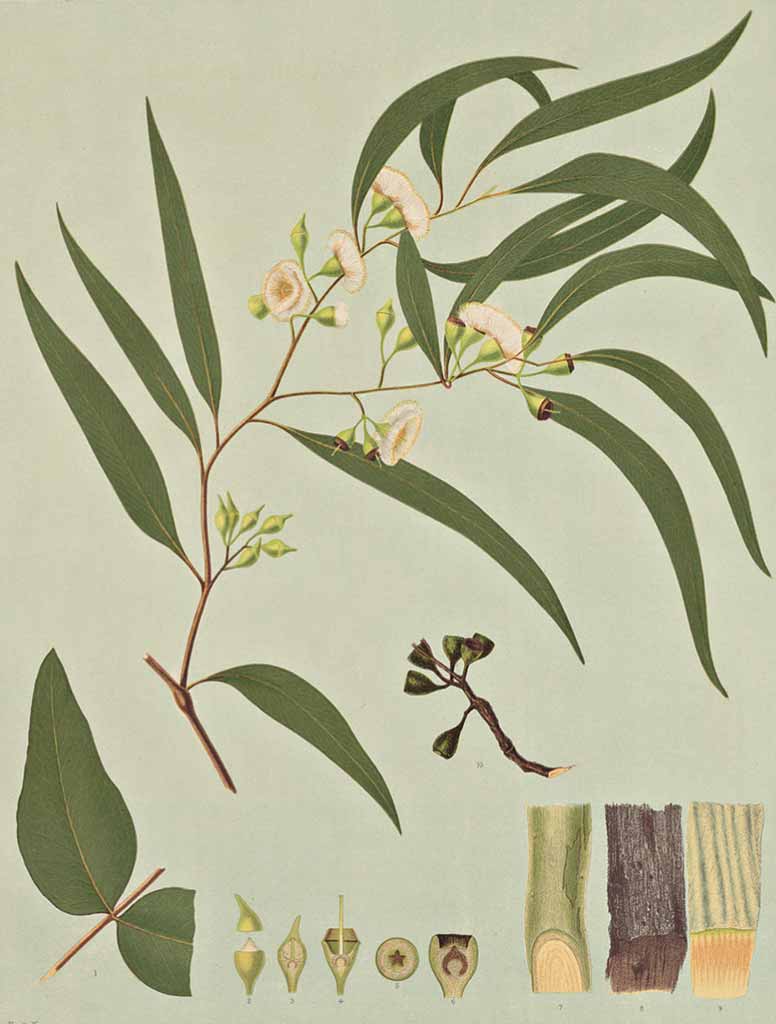

The first parts of Forest Flora were issued in 1882 and nine in total had been realised at the time of Brown’s departure, each containing five attractive lithographs of native plants that Rosa Fiveash had drawn as specimens came to hand, in no particular botanical order. Brown acknowledged that he had ‘received much valuable assistance in the elucidation and classification of the plants dealt with, from Baron Sir Ferd. Von Mueller, the assiduous and highly distinguished Government Botanist of Victoria’.

The book was widely praised, being recognised and used as an example of the progress of the colony. A report in The Advertiser of the part covering the white swamp gum, sawleaved scrub honeysuckle, common honeysuckle, stringy bark and sheoak was typical. It referred to the plates as ‘large and handsomely executed’, and the text as ‘terse, clear, and readable … altogether the work should be a most popular one’. Dignitaries were presented with copies, among them Pope Leo XIII in 1888, who ‘expressed himself as greatly delighted’ and awarded Brown a medal in commendation of his work. Copies were sent to the Calcutta International Exhibition of 1884, where the chromolithographs were much admired by artists and botanists.

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Eucalyptus gunnii 1882

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Banksia marginata 1882

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Eucalyptus leucoxylon 1882

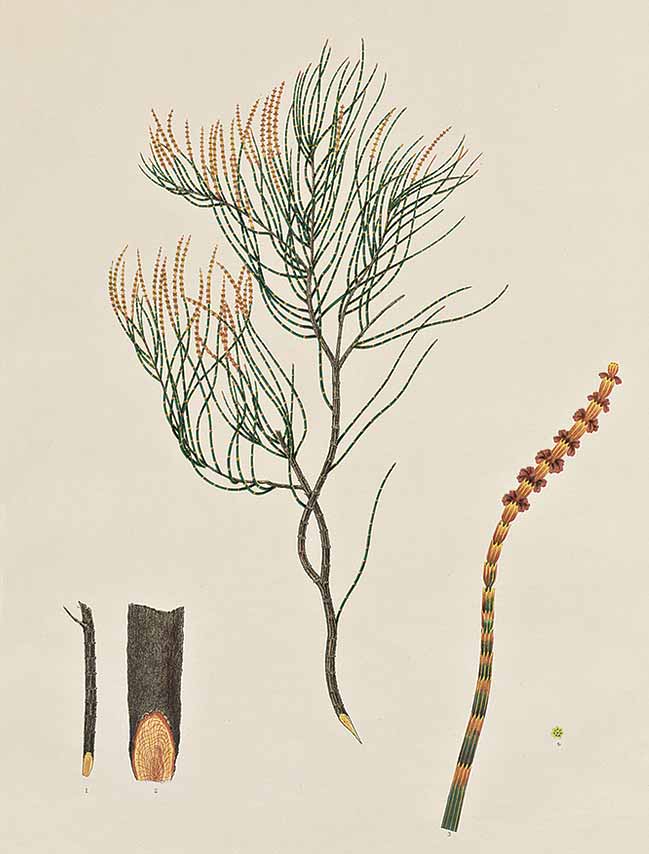

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Casuarina quadrivalvis 1882

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Eucalyptus leucoxylon var. macrocarpa (Red-flowering) 1882

In the South Australian Court of the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, drawings from Forest Flora were ‘faithfully reproduced upon the walls on an enlarged scale’ to ‘grand effect’. Also chosen to represent the colony was a pair of kookaburras painted by Fiveash, which ‘earns for its fair executant a good deal of well-merited approbation’. Adorning other walls were ‘beautiful sketches of the flora of South Australia’ by Rosa Fiveash, Mrs Strawbridge, Mrs Smart and Marie Wehl, the latter a niece of von Mueller.

Although Brown received most of the praise and publicity, Fiveash’s reputation was growing. In 1900 a portfolio of her paintings so impressed Governor Lord Tennyson and philanthropist Robert Barr Smith that they purchased them as a gift to the colony. However, Brown’s lithographer, H.W. Barrett, protested, writing a letter of complaint to the editor:

In your issue, of April 21, under the heading of ‘A valuable gift’, there appears a paragraph in which the name of Miss Fiveash figures somewhat conspicuously with regard to the production of the illustrations to the late John Ednie Brown’s ‘Forest Flora of South Australia,’ my share in that work being totally ignored.

Wishing to set the record straight, the disgruntled Barrett stated that Fiveash drew the main branches only and that Camilla Hammond and Mrs Smart drew one species each. He continued:

The remaining eleven plates and title page, together with all the additional work, consisting of the various woods, barks, seed vessels, botanical sections, and various details of the flowers, were drawn direct upon the stones from photos and natural specimens wholly and solely by me.

At the time, Rosa was overseas with her sister. She responded from London, sending similar letters to the editors of both major Adelaide broadsheets, defusing the situation by calmly and simply stating that Barrett was mistaken; the works purchased were not those used for Brown’s book:

Sir—There seems to be a little misunderstanding as to my collection of studies of wild flowers, which his Excellency the Governor, Lord Tennyson, and, I have since learnt, Mr. Barr Smith, purchased from me prior to my departure for England, doing me the great honor of presenting them to the Art Gallery of South Australia … These paintings never formed part of the 32 plates I did out of the 45 already published in the late J. Ednie Brown’s ‘Forest Flora of South Australia’, neither are they any of those still unpublished which I painted for the same book.

It appears that Lady Tennyson encouraged the purchase of Fiveash’s paintings. In March 1900 Fiveash and her sister were about to depart on an extended trip overseas following the receipt of a small inheritance. The Tennysons heard that Fiveash was planning to take the artwork with her out of the colony and intervened. Lady Tennyson wrote enthusiastically to her mother about the visit by the sisters:

We have just had two Miss Fiveashes up to show us the most lovely collection of the Australian wildflowers which one has done … I do not know anything about them but they are more or less ladies & well read, & kind little old maids. She would sell the whole of her collection for £200 which seems to me to be very little & I would give anything to have them.

By the end of the month a messenger had been sent to the Fiveashes’ house, the deal was done and the sisters were on their way to London. In England they visited the Worcester Porcelain Museum and other china makers where they were unimpressed by the designs that passed muster as Australian flowers. They also travelled through Italy soaking up the museums, artwork and antiquities.

Except for her two years overseas, Fiveash lived for her entire adult life with her sister Mary Emily, four years older, in the family home, Gable House, North Adelaide. Both were devout Anglicans and, as Lady Tennyson noted, remained unmarried.

The first time that Fiveash left the colony had been when she was a few months old. The last of the eight Adelaide-born children of businessman Richard Fiveash, originally from Kent, and his wife Margaret, only she and a sister and two brothers survived infancy. In November 1854, after the death of a child in April and Rosa’s birth in July, William and Margaret sailed for England on the John Hullett, presumably leaving the older children with family. The voyage was long and eventful—six and a half months in a leaky ship. A few days out of Adelaide the John Hullet started to take in water and struggled on her way around the Horn to Ascension Island where they put in for repairs.

The family story was that on the island the ship’s carpenter fell in love and decided to get married. The crew made a ring from a half-sovereign beaten on a marlin spike and fashioned a second ring from a threepenny piece as a souvenir for the ‘ship’s baby’, Rosa. Back at sea, the pumps had to be manned again, and passengers gave up their shoes so that the leather soles could be used as ‘suckers’ for the pumps. The Fiveashes had taken an Etna, a small heater for warming food for the baby by ‘igniting spirits of wine around the base to heat the milk in the hollow funnel’. No other heat was safe to use, so the captain and his officer also used it to heat their rum. Eighty years later, in 1934, Fiveash related the story to a reporter from The Mail (Adelaide), producing her mementoes from the voyage: the Etna, her baby ring and a hand stitched satin laced-boot made in England for her sister Emily.

Rear Garden of Botanical Artist Rosa Fiveash’s Residence in Ward Street, North Adelaide 1870s

A governess schooled the Fiveash girls at home. Anna Maria Bentham, best known for her bird paintings, is credited with giving Fiveash her first instruction in art. Bentham had come to Adelaide with her parents who, like the Fiveashes, were also from Kent and quite possibly knew the family.

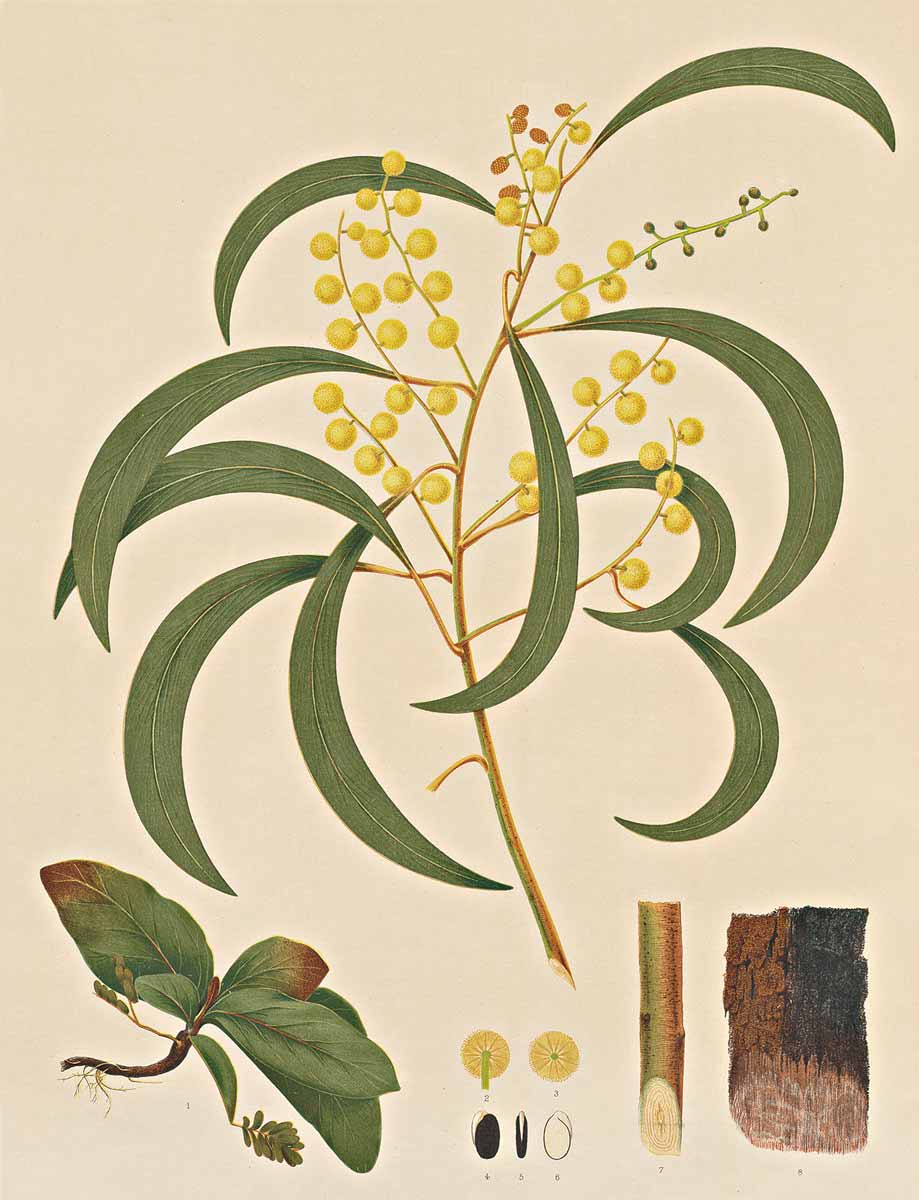

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Acacia pycnantha 1882

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Casuarina distyla (Female Plant) 1882

ROSA FIVEASH (ARTIST) AND H. BARRETT (LITHOGRAPHER), Casuarina distyla (Male Plant) 1882

After Fiveash’s father died suddenly in 1872 when she was 17, she took in some private pupils. When, in 1881, the School of Painting opened at the Adelaide School of Art and Design offering women the chance to become professionals, she and Bentham enrolled. Feminism was making headway; at the same time, the first women were attending Adelaide University.

Fiveash studied under Professor Louis Tannert and Mr H.V. Gill, who were proud of their many women pupils. Fiveash was a star student, garnering attention from art critics whenever she exhibited. Of the artwork exhibited by the 31 students in the class of 1883, according to The Advertiser:

The works which first call for notice in Mr Tannert’s exhibition are those from the pencil and brush of Miss Rosa C. Fiveash. This lady is an artist of considerable talent, and all her productions will bear critical examination.

The South Australian Register was similarly glowing, finding her flower studies ‘exceedingly clever and faithful … delicately yet boldly done in water-colours’.

In the same show, some of the chromolithographs from Forest Flora were on display. Fiveash owed these illustrations, her first commission in the scientific world, to lithographer H.W. Barrett. In the early 1880s, six pupils from the school of art were sent to the author, John Ednie Brown, to demonstrate their ability. In an interview made some 50 years later, Fiveash recalled that Barrett had chosen her, saying: ‘It’s the little one in black who will do it’.

Fiveash also recollected that samples of the flowering plants were posted to her in long cylinders from all over the colony and she worked from dawn to dusk transferring them to paper. She learned how to capture the detail necessary for true botanical illustration. Every flower ‘had to be measured with a fine rule, pinned down, and drawn to scale; and every shading, every gradation of color noted … and transferred to paper’. She made a few pencil lines as a starting point, then her ‘spider-like accuracy’ with brush and colour filled in the rest.

Fiveash had finished nearly 70 plates for Brown when the project fell through ‘for want of money’. Fiveash had intended to publish a new folio The Wild Flowers of South Australia and began work immediately, evidently with a backer, ‘many of the expenses attending it and that of the whole of the letterpress being borne by a gentleman residing in Fitzroy, North Adelaide’. But for unexplained reasons, the book did not eventuate.

Fiveash achieved high grades at the art school and in 1888, at the age of 34, gained her art teacher’s certificate from Adelaide and, three years later, accreditation from South Kensington, London. She then taught art privately for many years and at the school, Tormore House, in North Adelaide. She also returned to the art school to teach china painting from 1894 to 1896 after visiting Victoria in the 1880s to hone her technique and learn the firing process. China painting was fashionable in England during the Victorian era and many homes had a china cabinet. The art was a suitably feminine and domestic pursuit, well within the capabilities of women, a view that an 1872 journal article so condescendingly captured:

There is perhaps no branch of art more perfectly womanly and in every way desirable than painting on china. The character of the designs brings them within the reach of even moderate powers, and it must be admitted that painting flowers and birds and pretty landscapes, or children’s heads, is work in itself more suitable for women than men.

ROSA FIVEASH, Tremandreae, Tetratheca pilosa (ericifolia) c. 1887

But ideas about women, and fashions, were changing and declining demand saw the chinapainting class abandoned after 1896. Fiveash, however, continued making pieces for a couple of decades into the twentieth century, featuring Australian motifs. She also took on freelance scientific work, producing numerous crisp, bright scientific illustrations for Edward Stirling at the Adelaide museum, including the seven colourplates to accompany his description of a previously unknown marsupial mole in Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia (1890–1891) and, in 1908, Aboriginal artefacts collected at Lake Eyre.

When Stirling retired as Director of the museum late in 1912, he was presented with an illuminated address ‘contained in a morocco case, with an inner cover of worked copper, on which the professor’s monogram was embossed’. It was filled with paintings of diprotodons (extinct giant wombats), the marsupial mole, Aboriginal artefacts and other of Stirling’s discoveries:

The drawings had been entrusted to Miss R.C. Fiveash, and so fine had been her work that the Museum committee had decided to increase the amount she had asked for it.

Talented in many media, Fiveash also painted panels, a set of which was exhibited at the school of art in 1888, earning special mention by an anonymous art critic for The South Australian Register who felt that South Australia lagged in its art culture, but that her large screens were an exception. They were:

real works of art, tastefully designed and cleverly executed. These satin screens are covered with exquisite representations of flowers and foliage in natural colours, and the ground-work is old gold, blue, and red respectively. The old gold is most beautiful, and is in admirable taste.

Although she claimed never to have ventured into the field to collect plants, Fiveash was an active member of the field naturalists’ section of the Royal Society of South Australia. In 1902, Fiveash and Mueller’s great friend Ellis Rowan took part in the club’s excursion to Brown Hill Creek, where a fire two years previously and recent rains had left few flowering shrubs but plenty of orchids.

Fiveash’s best-known collaboration was to be on the orchids. It began a few years later with Richard Rogers and spanned 30 years, until her death. Fiveash’s ‘dear Doctor’ Rogers was a modest, genial and multi-talented physician, a hypnotist (scientific, not ‘black art’, he explained) and much involved in various professional institutions and boards. His interest in orchids began as a hobby, shared with his wife, Jean, which grew until he became the world authority on Australian species. He believed in nature education for the young and gave talks by radio in the public schools claiming that, with a little instruction, children as young as eight could recognise new orchids. Admiring Fiveash’s eye for detail, he persuaded her in 1908 to concentrate on orchids. She quickly developed an ‘orchid eye’, if not ‘orchid fever’—infectious but ‘the least painful of all fevers’, according to Rogers.

Fiveash provided the illustrations for Rogers’ publications and Rogers provided Fiveash with a set of Zeiss lenses and fresh specimens. Together they produced An Introduction to the Study of South Australian Orchids (1909), Some South Australian Orchids (1911) and a section for J. Black’s Flora of South Australia (1922). The orchid paintings found their way into several publications including some ‘beautiful coloured plates’ in Illustrated Australian Encyclopaedia (1926). A 1914 report in the Register observed:

Rogers’s descriptions … are no match for the stirring fidelity of Miss Rosa Fiveash’s brush. In these pictorial representations she has embodied perhaps her finest art. You unconsciously feel out to handle the flowers. Only the fragrance is missing, and the picture is so true that you can almost catch that too. Dr. Rogers, for whom this accomplished artist has been working these many years, is very sensitive over the precise botanical accuracy of the painted orchid, and he declares she has attained as near to perfection as is humanly possible.

ROSA FIVEASH, Eremophila freelingii, Eremophila oppositifolia, Eremophila maculata, Eremophila alternifolia

Fiveash resigned from The Society of Arts in 1913 after 21 years of membership, many on its council. She was still painting and winning awards in the 1920s but exhibited less and less. A report in The Mail (Adelaide) on the 1934 annual Society of Arts exhibition commented that she had not exhibited for some years but had been invited to contribute. At that show, Nora Heysen took out the main prize for a portrait with which ‘some exquisite flower studies from the brush of the veteran artist, Miss Rosa Fiveash’, formed ‘an interesting contrast’.

Writing about an exhibition by students at the School of Arts and Crafts in 1930, the principal wrote:

painting of wild flowers has attained a great vogue during recent years. Votaries of this branch of the art are carrying on the traditions in the work established by Miss Rowan and Miss Rosa Fiveash.

Quite possibly, Fiveash was unimpressed by the students’ work. A few years later she observed that young artists were ‘far too slap-dash’ and without a love of detail that she felt necessary in a good painter. For her, Victorian realism was still the standard. However, the art world was moving on, as reflected in the fate of the Fiveash paintings that Tennyson had secured: they moved from the Art Gallery (1900) to the South Australian Museum (1957) and finally to the Botanic Gardens of Adelaide (1979). She would have been disappointed. In 1932 she claimed that her great ambition was to have one of her studies of the Sturt Pea hung in the Art Gallery.

Then 78 years of age, Fiveash was described as ‘a dainty, charming, grey-haired old Lady’, dressed as from an earlier time, retired but still painting a little. Her eyes, ‘those eyes that were glued to the magnifying glass and the microscope not so long ago’, were ‘beginning to play tricks’. Still, her ‘slender white hands, the true hands of an artist, are just as steady and capable as in the days of 50 years ago, when she first began painting gum leaves’.

Rosa Fiveash in Her Adelaide Home 1907