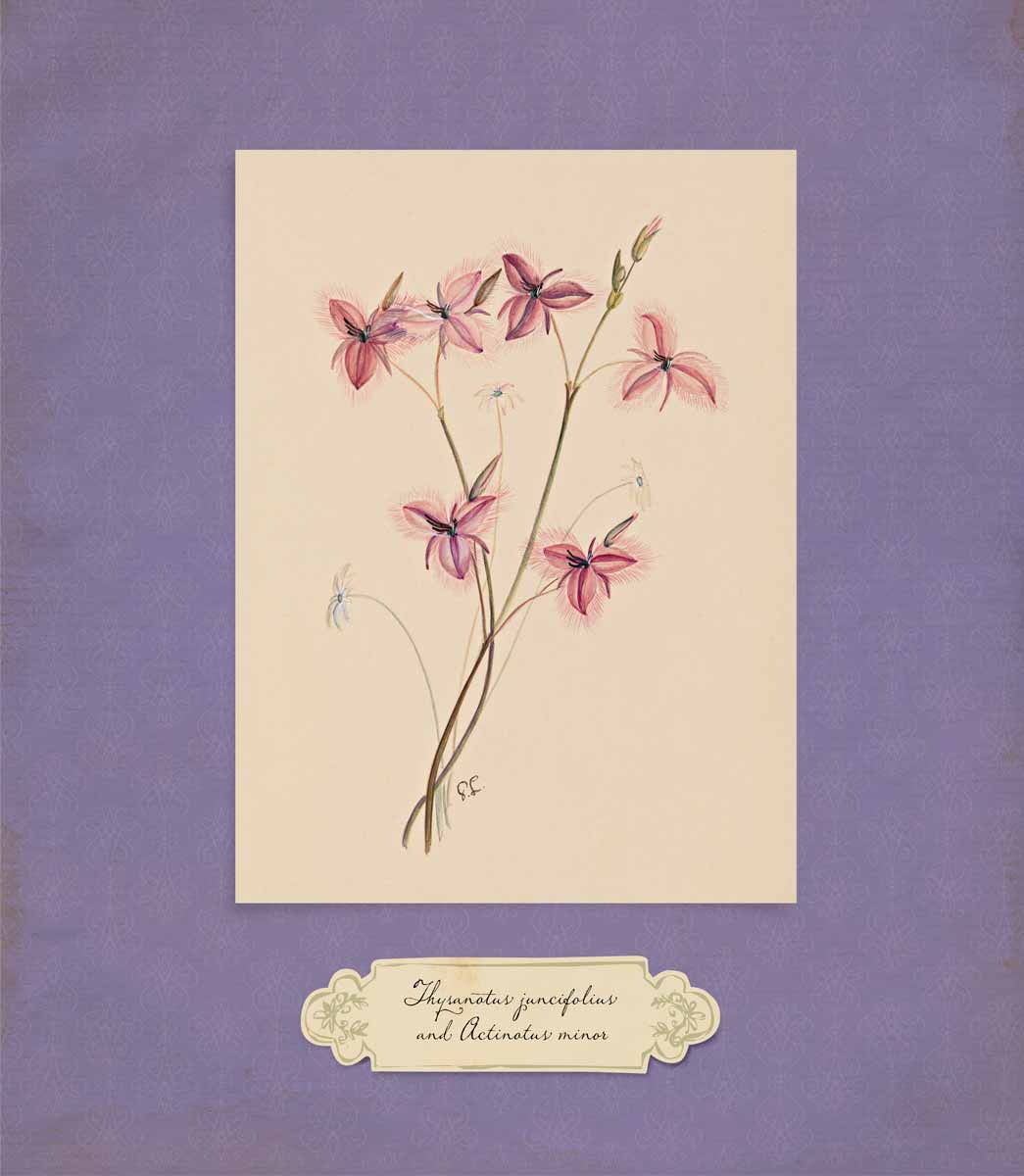

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Thysanotus juncifolius,Actinotus minor c. 1890

A DRAWING ROOM treasure

Gertrude Lovegrove 1859–1961

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Thysanotus juncifolius,Actinotus minor c. 1890

GERTRUDE (GATTIE) LOUISA LOVEGROVE’S FORAY INTO THE WORLD OF BOTANICAL illustration seems to have been as brief as the published details of her life. We now know that she was born at Terara in the Shoalhaven District, where the fertile river flats eventually became the orchard and dairy of Sydney, some 160 kilometres to the north. Her father, William Makepeace Lovegrove, went to the Shoalhaven initially to set up the Illawarra Steamship Company. He later served in various government positions including Clerk of Petty Sessions and Mayor. The Lovegroves were wealthy, well liked and actively involved in advancing the district. William helped set up the first church in the region on land provided by Mrs de Mestre, wife of Prosper de Mestre, sometime merchant, known for his breeding and ownership of successful racehorses. William Lovegrove married the de Mestre’s daughter, Melanie Isabella. They had nine healthy children, five daughters and four sons. Gertrude Louisa, born 11 August 1859, was the eldest daughter.

The Lovegroves’ two-storey home, Tulse Hill, in Terara, was named for William’s hometown in Surrey, England. Built of brick and stone and surrounded by ornamental trees, it was the venue for dances and other entertainments, often organised for a worthy cause. William was a gifted musician and artist of some merit. A reviewer of the 1873 New South Wales Academy of Art exhibition in Sydney observed that his landscapes ‘evince artistic skill of no mean ability’.

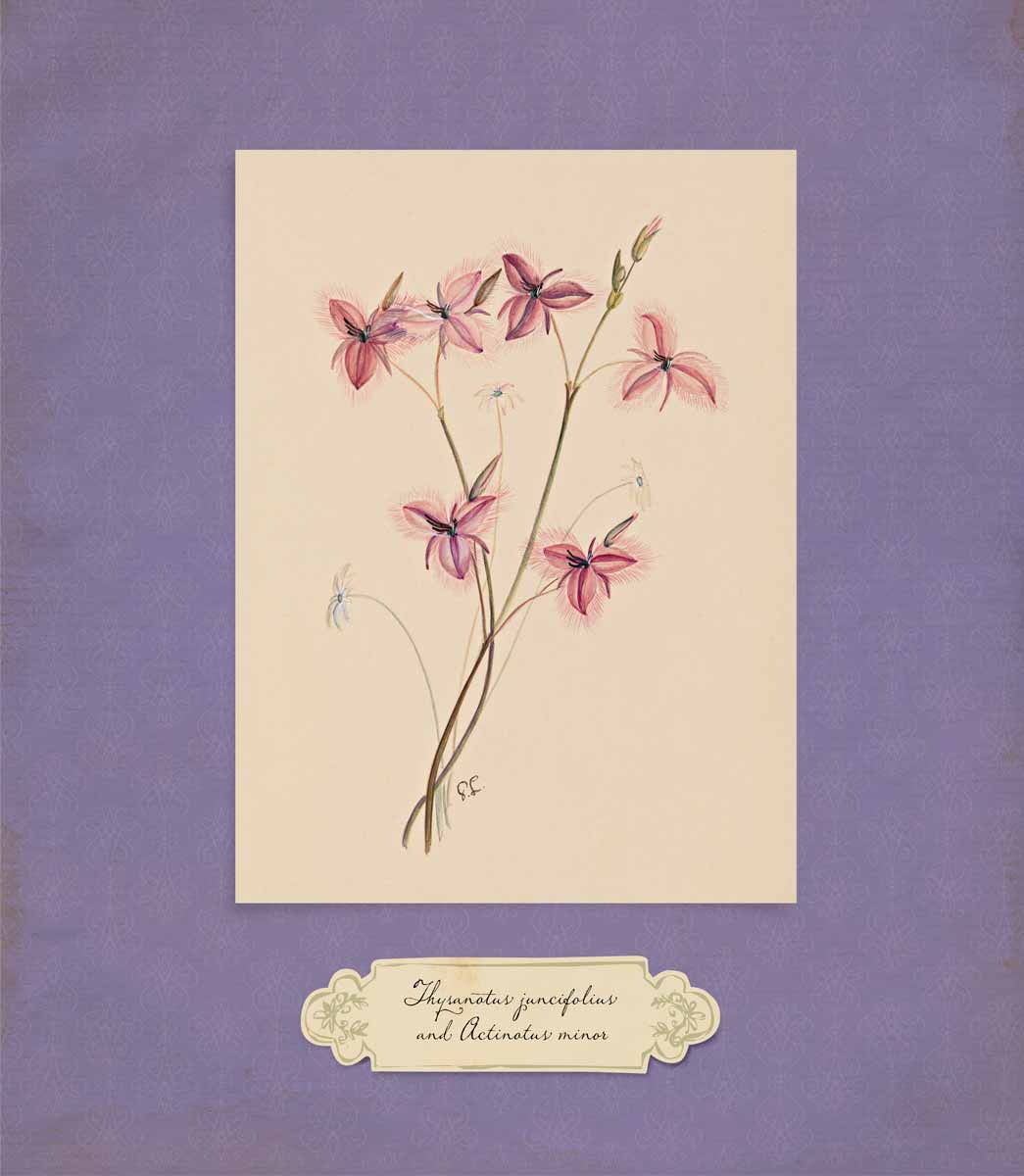

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Isopogon anemonifolius between 1865 and 1869

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Phaius orchid c. 1870

William had been keen to establish a Society of Arts in Terara. The first bricks of the building to house it were already laid when the big floods of 1870 intervened, sweeping away much of the town:

The spot where once stood the post-office, the telegraph office, the steam company’s store and wharf, where all was life, business and activity, is now one vast and vacant blank, and forms part of the Shoalhaven River.

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Isopogon anemonifolius, Stipandra glauca between 1865 and 1869

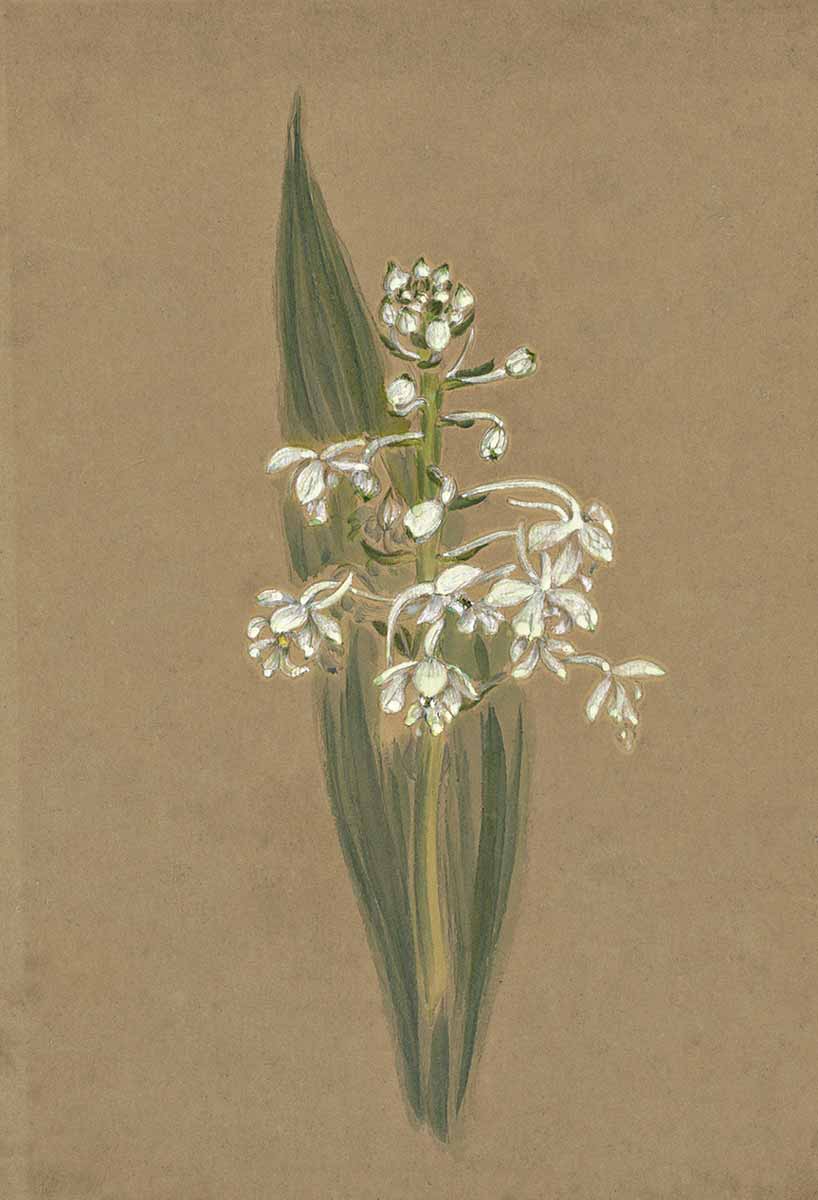

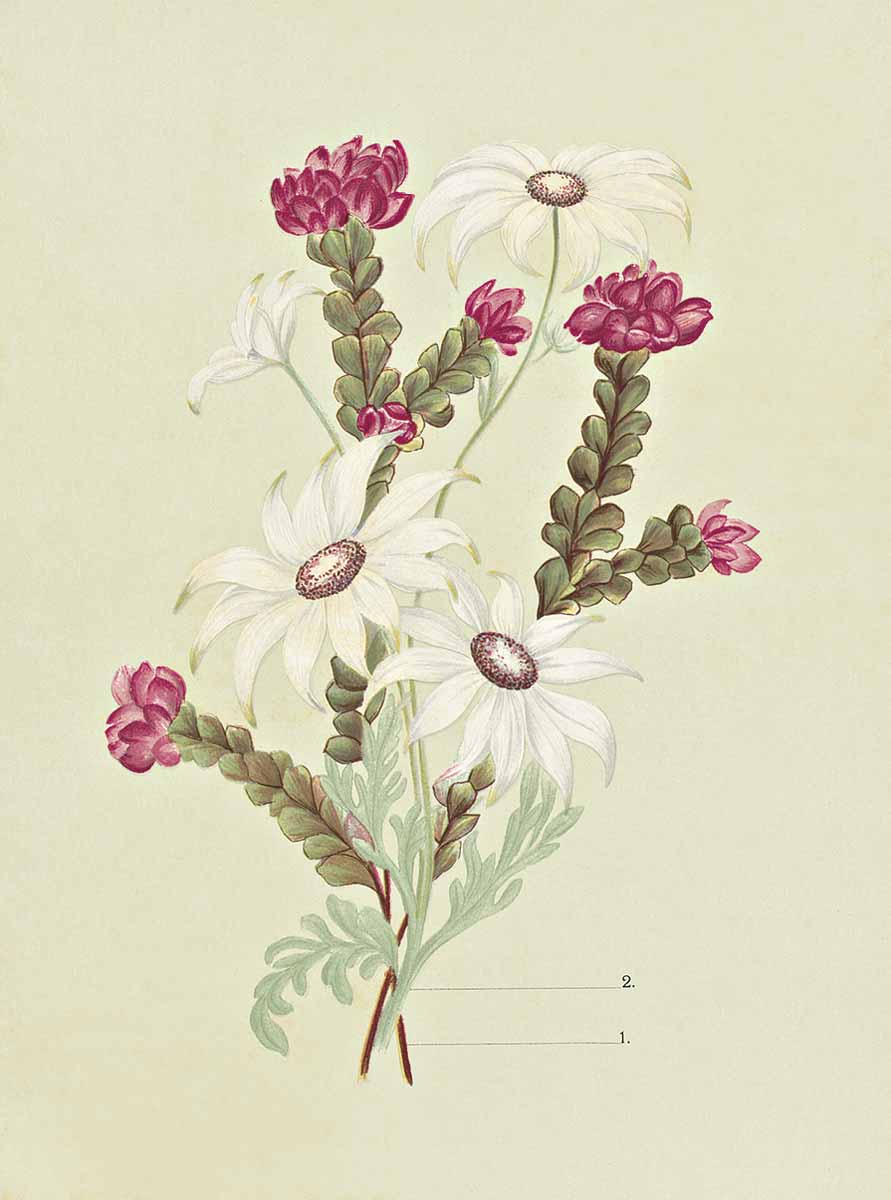

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, 1. Lobelia gracilis, 2. Abutilon halophilum 1891

Indeed, following this latest and most destructive display of the unpredictability of the river, the centre of development shifted from Terara to Nowra, although the Lovegroves stayed on at Terara. William’s wife established a multidenominational church at Tulse Hill and was remembered as a:

fine old lady of the Victorian period … [who] throughout her long life of 96 years, maintained the best traditions of the British stock which after her were steadfastly upheld by a family who found in her … very much to revere.

By 1888, the family had moved to Marrickville, Sydney, where William began again as a financial adviser and land agent. Before he left Terara, he disposed of 80 watercolours of local subjects by auction. It was at Marrickville that Gertrude Lovegrove may have met her future husband, Wilfred Blacket, a successful barrister. Alternatively, they could have become acquainted when Wilfred visited Terara on his District Court circuits. When both were 34 years old, they were married at St Clement’s Church, Marrickville, by Blacket’s brother, the Reverend Cuthbert Blacket. A few years later another Blacket brother married Gertrude’s younger sister, Rachel.

Gertrude was probably tutored at home but may have gone to the first school in the area, built in 1855, at nearby Worrigee. The family was well read and presumably Gertrude was encouraged in, if not taught, art by her father. Later records suggest that she had a love of wildflowers and carried on the family’s good works, organising art stalls and flower displays for charitable purposes. In April 1891, at the New South Wales Juvenile Industrial Exhibition, ‘Gertrude Lovegrove, Marrickville’ displayed a ‘specimen number of wildflowers of New South Wales’. The huge exhibition, attended by 2,000 people on a Saturday evening alone, was for pupils at technical schools, so possibly Lovegrove attended art school at a mature age, after the family moved to Sydney. Quite likely her wildflower paintings were from the book she began with William Baeuerlen (originally Wilhelm Baeuerlen, and often written Bäuerlen), The Wild Flowers of New South Wales, the first instalment of which was published just months before the exhibition.

In January 1891, the Shoalhaven Telegraph was sent an advance copy of Part 1 of The Wild Flowers of New South Wales, still incomplete because the printers in Edinburgh had forgotten to send the letterpress (the printed text) for plate 2. Part 1 was intended to be the first instalment of 25 parts, each with four plates, available to subscribers for five shillings or five-and-six including postage. Baeuerlen himself funded the print run of 250 copies, at a cost of 50 pounds. The copies arrived by December 1890, so the publication date of 1891, which appears on the title page, may actually have been the year previous to that commonly reported. Part 1 illustrated ‘eight well known and beautiful varieties’, two species per plate. A reviewer described it as an album of flowers, a ‘technical treatise—artistically, a drawing room treasure’, observing that as:

ably as the botanical description is written, it is the drawing and reproduction of the flowers in their exact colours … that will render the book most attractive to the unlearned in the science of botany, and to the student and lover of the botany of this colony.

The reviewer warned, however, that some common problems with publications ‘may beset the authors of this book; as the Australian public have not yet shown any very encouraging predilection for standard or even magazine literature of any kind’. They urged government to assist by purchasing copies for distribution and thought that the book was so attractive that if it was seen, subscription was more likely. The review was prescient, for no other parts were issued. The first instalment seems never to have received further publicity and was probably seen by few.

As well as distribution and marketing problems, Baeuerlen also had trouble with his employer at the Technological Museum (now Powerhouse Museum). In 1890, Joseph Maiden, a colleague of Mueller and the Curator at the Technological Museum, had employed Baeuerlen as a collector. The Assistant Curator, Richard Thomas Baker, objected to Baeuerlen publishing without Maiden’s permission, behaviour he considered improper for a public servant. Baeuerlen was forced to defend his position to Maiden. He stayed on at the museum until 1905, by which time the respected Maiden had moved on, leaving Baker in charge and tensions between the two men simmering.

Maiden was also Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society of New South Wales. He had met Baeuerlen when, on von Mueller’s recommendation, Baeuerlen was hired as the botanist on the society-funded Bonito expedition to Fly River, New Guinea. Lovegrove’s father, William, was also a member of the Society and corresponded with Baeuerlen, who had settled in the Shoalhaven district early in the 1880s. Baeuerlen was partly contracted to Mueller until about 1890, collecting mainly for him as far afield as Braidwood and the Southern Highlands. In August 1890 Baeuerlen wrote to Mueller:

My esteemed Baron … I am always a bit shy about sending you Eucalyptus specimens, but I think that this present one will be of interest and will not waste your time unnecessarily.

It was indeed a new species, collected on the Clyde Mountain, which Mueller named Eucalyptus baeuerlenii.

The Bonito expedition set off in June 1885 and by December there were reports in The Brisbane Courier and elsewhere that the explorers had been massacred by ‘natives’. William believed otherwise and was able to supply the Geographical Society with extracts of a letter from Baeuerlen that included everything, as he puts it, ‘that can touch on the subject of anxiety’.

After the expedition’s return in December, the plant specimens were sent to Mueller by rail. Maiden was to have brought them to Melbourne himself but was ill. Baeuerlen, a dedicated collector, was a difficult character. Mueller called him ‘circumspect and zealous’ and Maiden and Baker referred to him as a ‘painstaking botanical collector’. He got around on foot, by horse and trap, train and steamer, and was said even to have gone collecting plants on his wedding day.

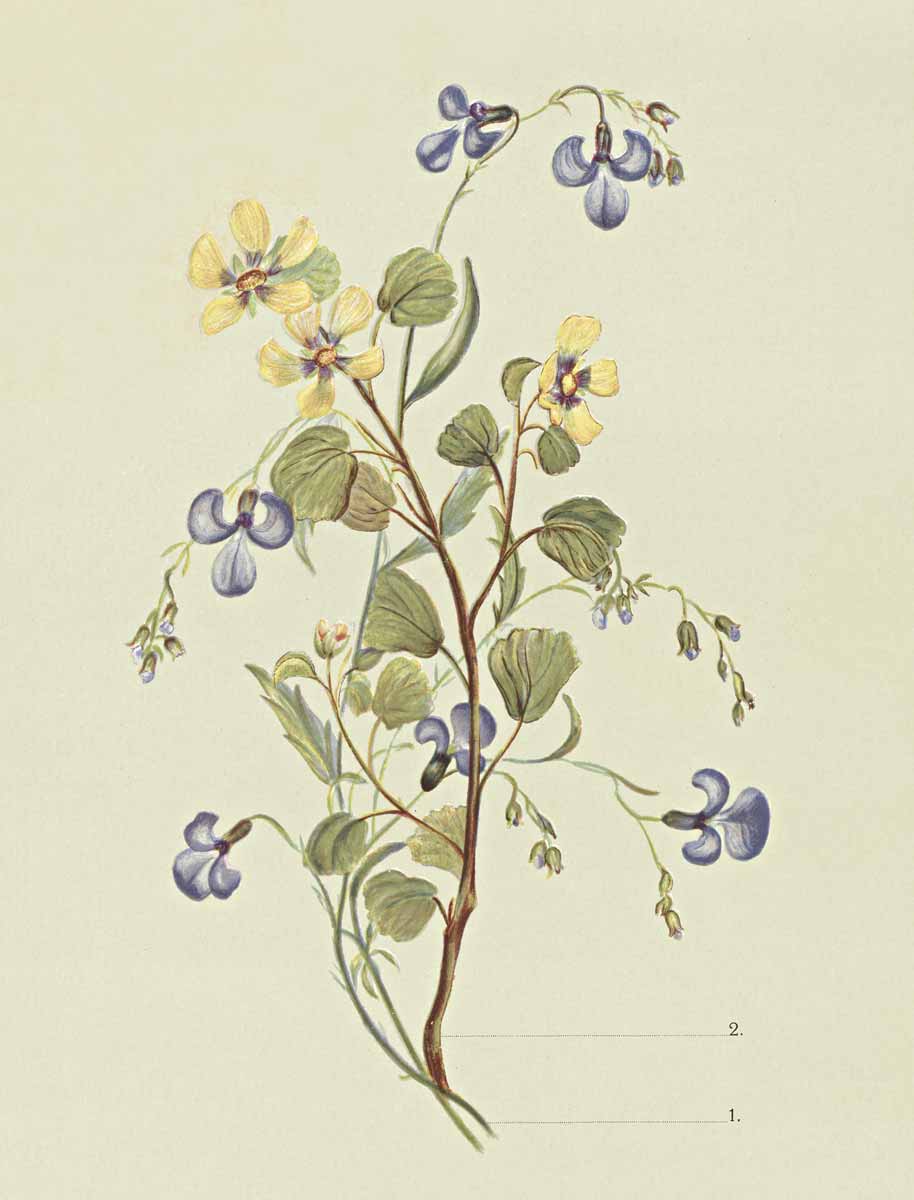

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Epacris impressa, Pimelia axiflora 1891 (detail)

Baeuerlen’s salary at the museum was a handsome 150 pounds per annum, which allowed him to buy books, including Brown’s Forest Flora of New South Wales, illustrated by Rosa Fiveash. It may have been this publication along with his generous salary that prompted him to produce an illustrated volume. The rage for wildflowers was so intense that there were concerns for their conservation around Sydney and a need for a book on their identification. Before her collaboration with Baeuerlen, Lovegrove would have been known to him through her father, and they may have been friends. Unusually, they shared authorship and the text suggests that it was a joint venture. For example, the text accompanying plate 2 uses the first person plural: ‘The two species illustrated in our second plate are two gems, rich if not rare, which are deservedly favourites with the public, and generally known at first glance’.

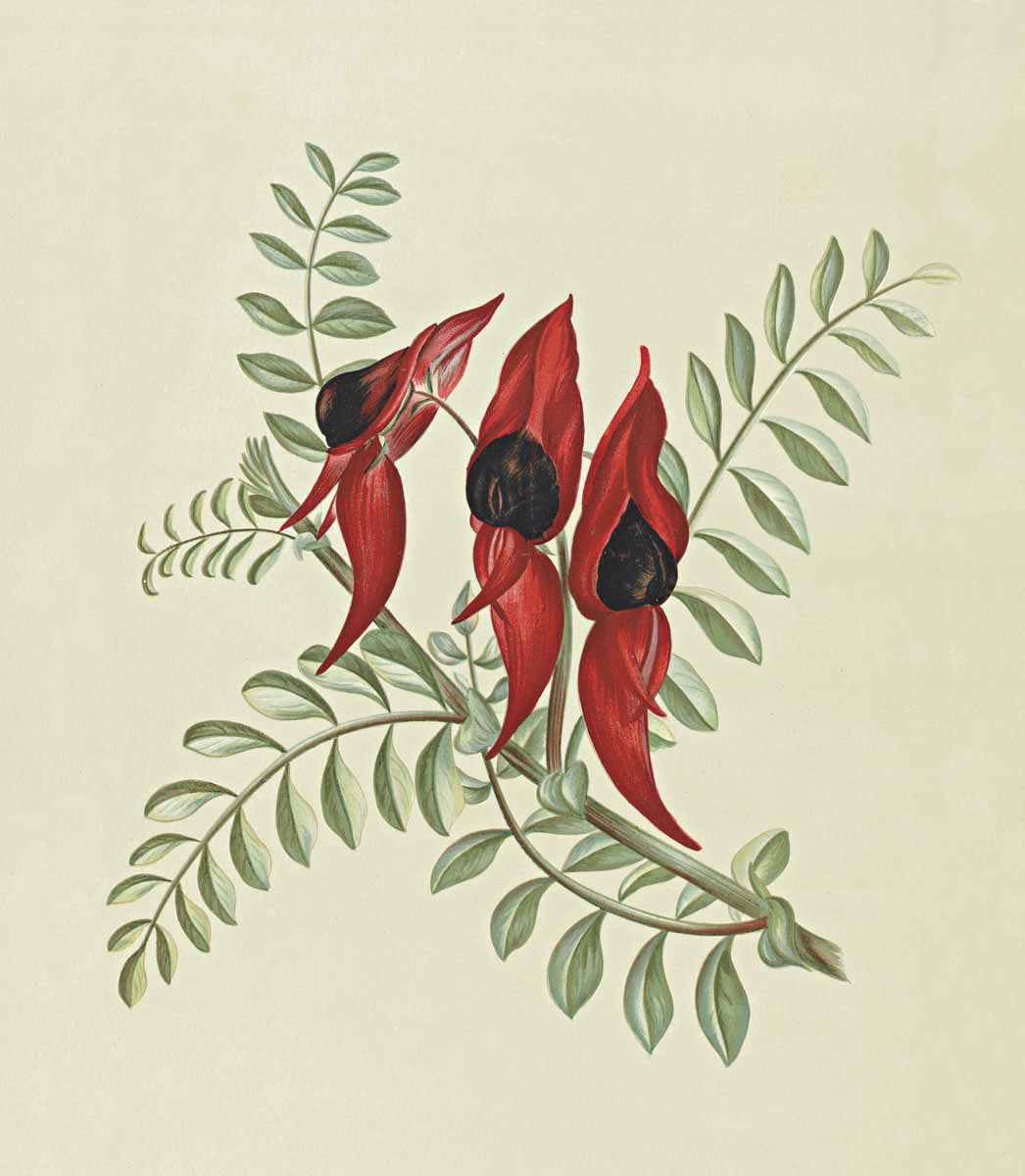

Baeuerlen published relatively little over his lifetime but his text for The Wild Flowers of New South Wales shows his passion for plants, their beauty and their uses. For example: ‘There can be no doubt that some of our Boronias contain medicinal properties, and others valuable scents, offering in that respect a wide and promising field for investigation’. Of Clianthus dampieri, then a well-established cultivated plant, he writes:

Fully to appreciate the beauty of this plant, one should see it in any of its native localities; when the traveller has wandered for hours over sandy and stony tracts, destitute of water, and destitute also of almost any vegetation, then when unexpectedly he comes to the dry bed of a shallow creek or water-course, where the Desert Pea trails its long shoots along the sand, with its soft, almost ashy-grey, leaves and large clusters of magnificent flowers rising up from the level of the sand, then he will indeed behold a sight which he is not likely to forget … But after copious or continuous rain, when the ‘Desert’ is not a desert, but rather a smiling flowergarden, then again should the Glory Pea be seen in its native haunts; then for richness, variety, and contrast of colour, the surroundings of the Desert Pea could hardly be equalled.

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, Clianthus dampieri 1891

As well as the four published plates, Lovegrove completed at least another 22 illustrations—three of which are in the National Library of Australia and 19 in the Mitchell Library at the State Library of New South Wales—some of which were presumably for future instalments of their planned series.

After her marriage, Lovegrove apparently assumed the role of a socially responsible wife of a prominent member of the New South Wales Bar, supporting worthy causes such as a home for consumptives. The left-leaning Blacket was by that time well established at the Bar ‘doing three or four men’s work’ and ‘carrying a large and varied practice’. He became a King’s Counsel in the High Court and was said to be a sharp wit and ‘inexhaustible, whether your need was a good case or a good story’. Outliving her husband by 23 years, Lovegrove died on 16 February 1961 at the great age of 101. Her life had spanned an entire century, from the tiny rural town of Terara, in the Victorian era, to Lindfield, Sydney, in the swinging sixties.

GERTRUDE LOVEGROVE, 1. Boronia serrulata, 2. Actinotus helianthi 1891