CHAPTER SEVEN

In pursuit of a ‘New World Order’: liberating Kuwait, 1990–1

Got a call this morning at 7.30 from Margaret Thatcher. She is staunch and strong and worries that there will be an erosion on force. She does not want to go back to the U.N. on use of force, nor do I. She does not want to compromise on the Kuwait government, nor do I. In essence, she has not ‘gone wobbly’ as she cautioned me a couple of weeks ago. I love that expression.

GEORGE H. W. BUSH, 7 SEPTEMBER 1990 1

I seem to smell the stench of appeasement in the air – the rather nauseating stench of appeasement.

MARGARET THATCHER, 30 October 1990 2

After the Cold War passed into history in the late 1980s, the arrival of a ‘New World Order’ was supposedly heralded by a war against Iraq after the latter had invaded Kuwait. After 1982 Thatcher, having added the Falklands experience to her historical database on the dangers of appeasement, was more convinced than ever of the rectitude of her wholehearted rejection of appeasement. In the case of Kuwait, such feelings were strengthened by the legacy of the British Empire. Indeed, given Britain’s previous hegemony in the region it is not too much to describe Britain’s diplomats as the midwives of Kuwaiti statehood. As US Secretary of State James Baker observed: ‘Kuwait had been carved out of Iraq by the British.’3 Kuwait, previously a protectorate within the British Empire, had long had great strategic importance for Britain. As Harold Macmillan noted: ‘Kuwait, with its massive oil production, is the key to the economic life of Britain – and of Europe.’4 On 19 June 1961, Kuwait and Britain signed a friendship agreement that replaced the protection agreement of 1899 whilst securing the independence of Kuwait.5 Only six days later Iraq declared its intention to annex Kuwait claiming that it had been an Iraqi territory (as part of the Ottoman territory of Basra) prior to the protection agreement of 1899.6 On 27 June 1961, the Emir of Kuwait requested assistance from the Saudi and British governments. Macmillan’s government then rapidly deployed troops, aircraft and ships to the area in Operation Vantage.7 By that time the issue of oil had, if anything, increased in importance for London.

Macmillan, so keen to engage in appeasement over Berlin, was resolution personified over Kuwait (although, of course, Iraq was no Soviet Union). In his diaries he revealed that, ‘remembering Suez’, he was careful to involve all of his senior ministers and, before deciding to commit forces, put matters before the entire Cabinet.9 He also, in contrast to Eden during the Suez affair, carried his senior military figures with him. Nevertheless,

Just as West Berlin represented an open-ended – and dangerous – commitment so, in confronting the Iraqi threat to Kuwait, the British government was faced with the economic cost of rejecting appeasement. This represented expenditure which economic limitations made unpalatable. This was especially so after the years 1955–6 (when, ironically, Macmillan had been chancellor of the exchequer) when, for the first time, the Treasury had achieved the ability to place a ceiling on defence expenditure.11 Fortunately, HMG was relieved of the Kuwaiti commitment when, in the autumn of 1961, British forces were replaced by a force from the Arab League.12 The British nevertheless remained alive to the dangers posed to their interests by any future threats to Kuwait’s security. Ted Heath, the lord privy seal, thus advised the Cabinet: ‘Our economic stake in Kuwait itself, and the central position of Kuwait to our oil operations in this whole area, are such that we should take all reasonable measures that we can to protect Kuwait.’13

The British defence secretary insisted that the United Kingdom retain a capability to assist Kuwait (although a request from the emir was deemed an essential prerequisite for any intervention).14 On 4 October 1963, after Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim had been killed in a coup, Iraq reaffirmed its acceptance of Kuwaiti sovereignty and the boundary it had agreed to in 1913 and 1932 in the ‘Agreed Minutes between the State of Kuwait and the Republic of Iraq Regarding the Restoration of Friendly Relations, Recognition, and Related Matters.’15 Matters had been resolved – on the local level by regional actors, and in the global arena by the discipline imposed by the Cold War. This situation was transformed, however, in the wake of Iraq’s exhausting war with Iran (1980–8) and with the end of the Cold War in 1989.

By 1990, Margaret Thatcher had grown in stature into one of the most eminent international politicians then in office. This was accompanied by an increasing tendency to concentrate policy making in her hands. She increasingly handled diplomacy herself as her annoyance with the ‘appeasing’ Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) had grown progressively throughout her premiership (greeting any perceived lack of resolution with the refrain ‘Typical Foreign Office’).16 Success in the Falklands War, and another election victory in June 1983, had afforded an increasingly strident Thatcher with the opportunity to wrest control of foreign policy from the FCO.17 Henceforth, her ‘personal diplomacy’ dominated the rest of her tenure in Downing Street. Thatcher held the FCO ‘type’ responsible for many past sins and saw direct parallels between the era of appeasement in the 1930s and the era of détente. She saw it as her job to repudiate the past, as well as the present, appeasing tendency in her diplomats. To Thatcher’s mind such people had betrayed Eastern Europe through appeasement at Munich, Yalta, East Berlin, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Helsinki. In 1990, when it seemed likely that Soviet troops would crush the Lithuanian freedom movement, she was told by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that Lithuania was an internal Soviet problem and the ‘Western leaders must not fall into [the] trap’ of thinking it was an international problem. Unmoved, Thatcher replied:

In 1987, when on a visit to Moscow, Thatcher told Gorbachev: ‘We were once mistaken about your plans in Czechoslovakia. We thought you would not invade [in 1968] because that would damage your prestige in the world. Yet we were mistaken. We do not want to repeat that mistake.’19 In September 1990 Thatcher visited Czechoslovakia itself (which had just divested itself of Communism in the ‘Velvet Revolution’). She came with an apology: ‘We failed you in 1938 when a disastrous policy of appeasement allowed Hitler to extinguish your independence. Churchill was quick to repudiate the Munich Agreement, but we still remember it with shame.’20 For Thatcher, resolution in the face of contemporary threats, and atonement for the past sins of appeasement, were two sides of the same coin.

On 2 August 1990 Thatcher, who happened to be on her way to the United States, reacted to the news of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in the same manner that she had responded to the Argentine invasion of the Falklands – by resolving to demonstrate that appeasement does not work. Recognizing the overwhelming importance of the US role, the prime minister immediately sought to stiffen the resolve of US President George H. W. Bush at a meeting in Aspen, Colorado.

Hitherto, the United States had undoubtedly pursued a policy that had sought to conciliate Iraq, despite Saddam’s aggressive rhetoric against Kuwait. Many observers denounced this as appeasement once Kuwait had been invaded and US ambivalence was reflected in Bush’s remarks of 2 August: ‘We’re not discussing intervention. I would not discuss any military options even if we’d agreed upon them. But one of the things I want to do at this meeting is hear from our Secretary of Defense, our Chairman, and others. But I’m not contemplating such action.’ And, when asked if the United States was to send troops to the region, Bush replied: ‘I’m not contemplating such action, and I again would not discuss it if I were.’22 This has since been taken as indicating a lack of resolve (especially amongst Thatcher’s acolytes). But this is hardly fair. In his diary the president reflected:

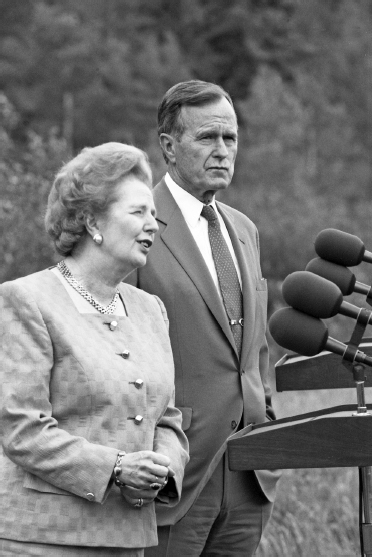

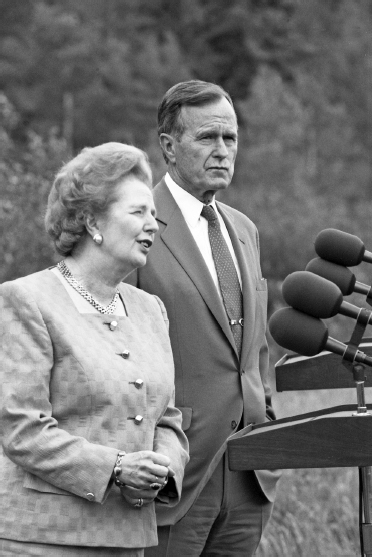

ILLUSTRATION 7.1 President George H. W. Bush and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, Aspen, 2 August 1990. Thatcher told the assembled press: ‘What has happened is a total violation of international law. You cannot have a situation where one country marches in and takes over another country which is a member of the United Nations.’

James Baker later seemed to apply the indelible mark of destiny on matters when he noted: ‘On that very day [2 August 1990], the President of the United States was preparing to meet with the Prime Minister of Great Britain, an iron lady not known for counseling half measures in time of challenge.’24 President Bush and National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft were certainly under no illusions that Thatcher was unambiguous with regard to her belief in the dangers arising from Saddam’s invasion.25 Acutely aware of public opinion, and an anti-appeaser by conviction and experience,26 Thatcher repeatedly invoked the 1930s analogy with regard to Iraqi invasion and occupation of Kuwait in 1990. She told Bush at Aspen on 2 August, in no uncertain terms: ‘First [of all], aggressors must never be appeased. We learned that to our cost in the 1930s.’27

Thatcher did not, contrary to popular mythology,28 tell the president that this was ‘no time to go wobbly’ (although she did give such advice a few weeks later).29 Yet, as Dilip Hiro noted in 1992, after the Aspen meeting, the president returned to the White House ‘reportedly at one with Thatcher’s rhetoric’.30 Despite this, Bush’s reputation as a vacillator, allied to his initial moderation on 2 August – and reflected in his temperate language – had given the impression that the president suffered from Chamberlainite indolence. And Thatcher, like Churchill, had, by this stage, generated sufficient attendant mythology to be able to claim to be the chief mover in the West’s response to Saddam’s aggression. As had been the case during the Falklands crisis, the United Nations (UN) was the first port of diplomatic call. On 3 August 1990, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 660, condemning the invasion of Kuwait and demanding that Iraq unconditionally withdraw.31 Thatcher later recalled:

These sentiments, as Gary Hess noted, were remarkably similar to those expressed on the Korean War by Truman in his memoirs.33 The respective images of Bush (as Chamberlain) and of Thatcher (as Churchill) survived the testimony of figures such as Thatcher’s press secretary, Sir Bernard Ingham, who later recalled that ‘George Bush had a backbone before he arrived in Aspen and did not acquire it from Mrs Thatcher . . . Her familiar distinctive contribution [was] a clear and simply expressed analysis of the situation.’34 This is a fair summation as Thatcher’s policy was, indeed, clear and free from any doubts. Keen to demonstrate his own resolution, Bush now adopted a Churchillian stance. On 5 August 1990, he stated:

The leadership of the United States was the essential ingredient in any attempt to restore Kuwait’s independence. If Saddam triumphed then any number of Gulf states would be at risk. Saddam, a new Nasser, would cast envious eyes across the region. Thatcher thus urged that ‘we must do everything possible’ to stop Saddam.36 This included offering military assistance to King Fahd of Saudi Arabia. In fact, the US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney rang Bush while the latter was in conference with Thatcher to tell her that Saudi Arabia had requested US troops (after some effective lobbying – on the subject of the Iraqi threat – by Cheney himself).37 The Saudi monarch agreed immediately to accept 100,000 American troops in his country at once38 (with the provisos that the United States keep the initial deployment secret; that there be no attack on Saddam without consultation; and that the troops leave after the threat from Saddam receded).39 With ‘Desert Shield’ in place, Thatcher now urged Bush to prepare for war (‘Desert Storm’) in earnest. In doing this she drew upon her experiences in the Falklands War: ‘As so often over these months [during Operation Desert Shield] I found myself reliving in an only slightly different form my experiences of the build-up to the battle for the Falklands.’40 Signally, Thatcher told Bush how she had reversed the Argentine seizure of the Falkland Islands in 1982.41

On August 6, Thatcher met Bush once more. She urged him to invoke Article 51 of the UN Charter (the right of member states to self-defence). Thatcher’s sense of rectitude far outweighed that of Bush, however (Baker later described Thatcher as ‘a charter member of a school that may be described as do what you must now and worry about it later’.)42 Bush was now firmly on board the anti-appeasement wagon, a fact that was reflected in the rhetoric of the president (himself a highly-decorated veteran of the Second World War). On 8 August, Bush told the American people that ‘if history teaches us anything, it is that we must resist aggression or it will destroy our freedoms. Appeasement does not work. As was the case in the 1930’s, we see in Saddam Hussein an aggressive dictator threatening his neighbors.’43 At the Pentagon on 15 August Bush stated: ‘A half century ago . . . the world paid dearly for appeasing an aggressor who should, and could, have been stopped. We are not going to make that mistake again.’44 The massive build-up of allied forces in Saudi Arabia led the Conservative MP Alan Clark, a junior minister in the UK ministry of defence, to conclude that war was ‘almost inevitable. It is the railway timetables of 1914, and the Guns of August.’ In the spirit of ‘war by timetable’, Thatcher warned Bush on 17 October that any war would have to be won before the end of the campaigning season in March 1991.45 In the meantime, Bush prepared the American people for war by denouncing appeasement in, of all places, Prague.

On Thanksgiving Day, 22 November 1990, Bush declared: ‘In World War II, the world paid dearly for appeasing an aggressor who could have been stopped early on. We’re not going to make that mistake again. We will not appease this aggressor.’47 The president had, decidedly, not gone ‘wobbly’. Thatcher, the conviction politician, having successfully led the nation through a war in the Falklands, now saw herself in Churchillian terms. And, like Churchill, Thatcher sought to stiffen the nation’s resolve through rhetoric. On 6 September 1990, Thatcher told the House of Commons:

Thatcher’s instincts about the appeasing ‘type’ were confirmed in the run-up to the liberation of Kuwait by the US-led coalition in 1991. When Edward Heath, a former prime minister and a staunch opponent of appeasement in the 1930s, visited Iraq in the autumn of 1990 in order to persuade Saddam to release the British nationals he had seized, the charge of appeasement was widely made, not least by Thatcher herself49 (whom Heath hated). The headlines in British tabloids were predictably lurid, with examples including ‘Heath: Appease Saddam’ (the Daily Express); ‘Traitor Ted’ (the Sun) and ‘Fury at Ted the Traitor’ (the Daily Star).50 Thatcher, who later compared ‘Western weakness’ towards Saddam with the appeasement of Hitler,51 showed her contempt for those who sought to parley with Saddam by declaring in the Commons: ‘I seem to smell the stench of appeasement in the air – the rather nauseating stench of appeasement.’52 Of would-be ‘appeasers’, Thatcher later recalled: ‘There is never any lack of people anxious to avoid the use of force. No matter how little chance there is of negotiations succeeding – no matter how many difficulties are created for the troops who are trying to prepare themselves for war – the case is always made for yet another piece of last-ditch diplomacy.’ Thatcher told Mikhail Gorbachev’s ‘peace’ envoy Yevgeny Primakov that Saddam ‘must not be appeased.’53 Against this, there remained those who questioned the manner in which all and any negotiations were denounced as appeasement. Labour’s Tam Dayell asked Heath if he ‘agree[d] that part of the difficulty is the confusion which equates dialogue with appeasement, when dialogue and appeasement are very different matters’? Heath replied:

Despite such pleas, Saddam was continually, and successfully, depicted as ‘another Hitler’ in the West. It naturally followed that the appeasement of Saddam threatened a repeat performance of the Second World War. The success of this rhetorical strategy led two commentators to observe: ‘It would not be a great exaggeration to say that the United States went to war [with Iraq in 1991] over an analogy.’55 In addition to invoking the spectre of the 1930s, leading figures in the Bush administration repeatedly mentioned the Vietnam War as a framework for the invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent war.56 Vietnam stood, of course, as the American equivalent of Britain’s own national debacle, Suez. In 1990, patriotic Americans hoped that a war to liberate Kuwait would emulate the virtue of the Second World War and simultaneously re-cast Vietnam as a ‘good war’. The references to the Second World War therefore had a dual role: to justify the coming war, and to ‘rescue’ the Vietnam War.

On 31 December 1990, in a private letter to his children, Bush wrote of the coming conflict in the Gulf and asked: ‘How many lives might have been saved if appeasement had given way to force earlier on in the late 30s or early 40s? How many Jews might have been spared the gas chambers, or how many Polish patriots might be alive today? I look at today’s crisis as “good” vs. “evil”. Yes, it is that clear.’57 Once the war of 1991 had liberated Kuwait, Bush continued to invoke the 1930s and 1940s in relation to Iraq and Kuwait. He wrote: ‘I saw a direct analogy between what was occurring in Kuwait and what the Nazis had done, especially in Poland.’ He also wrote that even though he had been criticized for comparing Hitler and Hussein, ‘I still feel it was an appropriate one’.58 Bush also seemed intent on exorcising the ghosts of Vietnam59 by means of waging a war in the Persian Gulf that, in turn, was justified by a desire to atone for the sins of the 1930s. In 1992, one polemicist wrote:

Of course, such conclusions privileged the means of the morality of telling truth in politics over any ends of driving Saddam from Kuwait. For such critics Bush’s wedding of national self-interest with morality in a new Jeffersonian paradigm61 was a smokescreen for Realpolitik. Against this, Thatcher expressed fears that the international community risked repeating the errors of the 1930s by failing to match rhetoric with resolution.

In the event, Thatcher was forced to resign as prime minister in November 1990, before the liberation of Kuwait began. But she had played her role to the full. For her adherents, Thatcher’s role in the formation of the coalition in 1990 set the seal upon her place as the arch British anti-appeaser of the postwar era. It coincided with the end of the Cold War that Nicholas Ridley, employing a certain level of hyperbole, asserted had been ended by the same coalition (of the United States, the Soviet Union and Britain) that had sought to perpetuate the wartime ‘Grand Alliance’ at Yalta in 1945. For Ridley, Thatcher’s place in history was assured as ‘[t]he victories in the Falklands War and the Gulf War were largely due to her resolution.’63 Thatcher had, it was true, acquired a formidable international reputation through her principled foreign policies. In her victorious 1987 election campaign she had also benefitted from her willingness to negotiate from strength64 (famously declaring that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was a man she ‘could do business with’).65 By 1990, however, her perceived intransigence and combative style was becoming increasingly unpopular with the electorate. This alarmed many MPs in Britain’s ruling Conservative Party and internal opposition brought her down in November 1990.66 By this stage Thatcher believed much of her own propaganda and in her memoirs she compared her fall with Churchill’s ejection by the electorate in July 1945 (‘democracy is no respecter of persons’). Typically, she viewed the advice of several of her senior Cabinet colleagues to resign (after failing to win the Conservative leadership on a first ballot) in Hobbesian terms. ‘I was sick at heart . . . what grieved me was the desertion of those I had considered friends and allies into the weasel words whereby they had transmuted their betrayal into frank advice and concern for my fate.’67 On the international stage, it seemed that Thatcher’s confrontational approach to foreign affairs had been rendered obsolescent, as the Cold War had passed into history. Within a year events in the dying state of Yugoslavia would give her fall, and her rhetoric, added poignancy.