CONCLUSION

Appeasement, British foreign policy and history

I trust that a graduate student some day will write a doctoral essay on the influence of the Munich analogy on the subsequent history of the 20th century. Perhaps in the end he will conclude that the multitude of errors committed in the name of ‘Munich’ may exceed the original error of 1938.

ARTHUR SCHLESINGER, Jr 1

The invocation of appeasement as an evil, designed to perform any number of political tasks in the international and domestic arenas, has been an enduring feature of foreign policy debates since 1945. And, if history shows anything, it shows that this usually worked. This was due, in no small part, to the association of Munich with humiliating shame and with abject failure. This was felt keenly throughout the British nation as individuals, and not always ‘Great Men’, recalled their own role in the tragedy of Chamberlainite appeasement. James Callaghan, a man of moderate views who had become prime minister in 1976, demonstrated this as well as anyone when he wrote: ‘I still recall the mingled relief and shame with which I heard the news of the Munich settlement . . . I was ashamed of feeling such relief, and ashamed too for the action of my country in unjustly sacrificing the Czechs to an evil dictator.’2 In 1990 Lord Annan identified the baleful effect that appeasement had had upon the British national psyche.

In a similar vein, and reflecting upon the distortions imposed on British postwar history by the legacy of the 1930s, Brian Harrison identified the ‘appeasement story’ as ‘doubly harmful’ as it had been repeatedly used ‘as an emotive reach-me-down self-justificatory device in overseas or domestic situations which seemed to demand resolute action. The resolute action may have been needed, but the parallel was misleading – whether in Eden’s handling of Nasser in 1956, Heath’s handling of the miners in 1973–4, or of Thatcher’s of Galtieri in 1982.’4 This state of affairs was rooted in the failure of Idealism in the interwar period, which led to conciliatory diplomacy was castigated as being synonymous with appeasement (the consequence of which was the semi-hegemony of the Realist worldview in the formulation of British foreign policy after 1945).5 Since the Second World War, statesmen and women have repeatedly invoked an abhorrence of appeasement as the ultimate justification for action in foreign policy. As Paul Kennedy wrote in 1976: ‘Even today, while a foreign policy rooted in those traditional elements of morality, economy and prudence may be – indeed, is likely to be being – carried out, the last thing its executioners would desire would be to have the word “Appeasement” attached to it.’6 We can certainly choose any number of decision-makers who have more or less asserted, as President Ronald Reagan did in 1986, that those ‘who remember their history understand . . . that there is no security, no safety, in the appeasement of evil’.7 In 2010, Paul Kennedy reflected on the unchanging nature of debates on what he termed ‘the “A” word’:

Appeasement remains at the very centre of the ‘history wars’ in which competing political narratives seek to appropriate the past so as to achieve an intellectual ascendancy when debating wars and crises. When policy makers claim to have ‘learned from history’ they are immediately brought under media scrutiny, often by high-profile ‘media dons’ whose opinions are littered with allusions to events that were once common knowledge in British Grammar schools. Of course, such exercises have far more to do with modern mass democracy than with academic history. In the volume of his history of the Second World War that dealt with Chamberlainite appeasement, Winston Churchill, who so shaped the postwar debates on appeasement, assessed what exactly could be learned from what he termed the ‘tragedy of Munich’.

This nuanced view was, however, largely swept away by the simplicity of the ‘Guilty Men’ thesis, which Churchill himself did much to propagate. Donald Watt asserted in 1993 that Churchill’s ‘alternative to British policy [in the 1930s] lies . . . in the area of counterfactual history . . . The dismissal of all policy options save conflict as “appeasement”, and the constant reiteration of the adage “appeasement never pays”, are together one of the legacies of the Churchillian legend.’10 The Churchillian rhetoric directed at Munich was crucial in damning the diplomacy of appeasement by means of phrases such as ‘we have sustained a defeat without a war, the consequences of which will travel far with us along our road’.11 That Chamberlain failed in his policy of appeasement is what most people recall first. That he failed while in pursuit of a policy now widely regarded as immoral is what damns him for all time. Hans J. Morgenthau noted that Chamberlain’s appeasement was ‘inspired by good motives; he was probably less motivated by considerations of personal power than were many other British prime ministers, and he sought to preserve peace and to assure the happiness of all concerned. Yet his policies helped to make the Second World War inevitable, and to bring untold miseries to millions.’12 The damnation arising from failure had been clear to Jan Masaryk, Czechoslovak ambassador to London, when he told Chamberlain and Halifax: ‘If you have sacrificed my nation to preserve the peace of the world, I shall be the first to applaud you. But, if not gentlemen, God help your souls.’13 And, indeed the repudiation of the appeasement of Nazi Germany led to a rejection of appeasement per se. This was not only unhelpful, it was impossible – as if one suddenly announced that ‘reason’ or ‘conciliation’ had no place in the conduct of diplomacy. We can thus view the post-1945 continuities in British foreign policy through a prism where the ‘A’ word was studiously avoided (although, on occasion, the ‘D’ word (détente) was substituted for it).

The need to be seen to observe the ‘lessons’ of appeasement, not least by avoiding the use of the ‘A’ word, has been a constant consideration for policy makers – wherever they have figured within the history of British foreign relations. The primary instances of the impact of this on the conduct of British foreign policy include Attlee and Bevin’s opposition to global Communism, Eden’s stand against Nasser, Thatcher’s refusal to yield to Argentine and Iraqi aggression, and Blair’s moralizing interventionism. In those instances in which I have identified a British government as following at least some of the defining features of an appeasement policy – those of Macmillan over Berlin and of Major and Hurd over Bosnia – the same awareness of the ‘rules’ of postwar international relations applied. In these cases, the British government was careful to frame debates in terms of a desire to avoid escalation. And, so long as the label of appeaser was successfully fended off, there were good reasons for Macmillan and Hurd to pursue their policies. This is due not least to the fact that the proportion of the public that proved receptive to Chamberlain’s rhetoric about avoiding war has, if anything, increased. Donald Watt notes that those post-1945 governments who have invoked the ‘lessons of appeasement’, have not always been successful. The United States ‘in 1950, as in 1990, found, as did Britain in 1935, that taking the lead against an aggressor in the name of the world community risks many of its members seeing the resultant conflict as bilateral rather than collective in nature.’ Furthermore, US references ‘to the experience of the 1930s won . . . it little support in Britain in 1965–6 for its involvement in Vietnam.’ Such are the limits of historical analogy for policy ends.’14

Macmillan’s policy of appeasement over Berlin entailed an emphasis on the danger of nuclear war over what were, in his view, essentially trifling issues. Robert Jervis notes that although the fear of being tarred as appeasers in the Munich tradition was strong, it was outweighed by the fear of nuclear war.15 Here, Macmillan was right to have recognized the way in which nuclear weapons had undermined the rationale for putting strength before negotiation. As Aneurin Bevan observed in 1956:

This is not to say that wars which did not involve the potential for nuclear war were easy to deal with. By the time of the Bosnian conflict in the 1990s, British policy dictated that the ethnic and intractable nature of the war required its isolation and containment. In both cases, the rights and wrongs of the matter were quite irrelevant. In Berlin and in Bosnia, although the British again chose the ‘dishonourable’ path, British policy was justified by references to what had happened in the summer of 1914 (while Macmillan’s and Hurd’s detractors preferred to make their analogies in reference to the autumn of 1938). At this juncture we might usefully recall debates on whether or not history instructs on an applied (or even a theoretical) plane. In answer to the question ‘Does History repeat itself?’ Sir Lewis Namier remarked:

In today’s world, politicians remain keenly aware that an ability to identify their cause with that of the anti-appeasers or with the victims of Nazi aggression in the 1930s is an invaluable diplomatic asset. In December 2012, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamen Netanyahu articulated the historical lessons that he had drawn from the appeasement of Hitler. After Czechoslovakia had been sacrificed at Munich, the ‘international community [had] applauded almost uniformly [and] without exception . . . [believing] that [this] would bring peace, peace in our time they said. But rather than bring peace, those forced concessions from Czechoslovakia paved the way to the worst war in history.’18 A few days later, Israel’s foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman, expressed his government’s anger over Palestinian diplomatic gains by comparing Israel’s situation to that of Czechoslovakia in 1938 – before that state’s betrayal by the West and destruction by the Nazis. Lieberman contrasted Western irresolution with Israel’s determination to resist appeasement: ‘When push comes to shove, many key leaders would be willing to sacrifice Israel without batting an eyelid in order to appease Islamic radicals and ensure quiet for themselves . . . We are not willing to become a second Czechoslovakia and sacrifice vital security interests.’ Lieberman suggested that the reason for this appeasement was simple: Western self-interest derived from ‘their need for Arab oil’ and Muslim markets.19 Lieberman’s use of such rhetoric was perceptive for its understanding of his target audience. For, although Western publics care little for Israel’s security, ‘appeasement’ and ‘Munich’ remain bywords for the failure of Western diplomacy, a diplomacy that betrayed peace and Czechoslovakia in 1938. By invoking such a view of history any statesman or stateswoman had long been able to assume the mantle of moral superiority. In such a worldview the security of the strong can only be assured by self-reliance, and of the weak by an ascendant morality in the conduct of international relations. In this vein of thought Lieberman asserted:

After the Cuban Missile Crisis, the success of President Kennedy’s propaganda machine pioneered the model of the informed leader learning from history. This still plays well with Western publics – although political opponents and the media are keen to disabuse audiences of the notion of the rational scholar-statesman. Nevertheless, the accepted narrative of the course of appeasement in the 1930s had provided British governments with an allegory that could be of considerable utility in justifying an active foreign policy. Ernest Bevin told the Labour Party Conference in 1950:

In 1935, Bevin had denounced pacifism and appeasement in the Labour Party.22 By 1950, Bevin’s argument was in the ascendancy in British society. It was, indeed, something approaching orthodoxy. But appeasement did not disappear from British foreign policy formulation after 1945. Indeed, it was impossible for it to do so as its definition is, inevitably, elastic and entirely subjective. It was actually inevitable that, on occasion, diminishing British power had increased its (near-forbidden) utility. In actual fact, the appeasement ‘tradition’ continued throughout the postwar era (often under the banner of ‘pragmatism’) and its employment was seen by its Foreign Office proponents as something to be proud of. Richard Luce (minister of state at the FCO, 1981–2 and 1983–6) phrased matters thus:

Such thinking was shared by Douglas Hurd, who saw impartiality as an essential part of the diplomat’s world view. In practice, this was hugely controversial and Anthony Lewis opined that, over Bosnia, ‘Hurd put one in mind of Chamberlain and Halifax.’24 In assessing these powerful men, one might usefully recall the words of John Adams.

Ed Vulliamy, a journalist who was among Hurd’s fiercest critics over Bosnia, observed: ‘To construct an argument for neutrality, one has to equate the perpetrator and the victim of violence, thus removing any ethical imperative.’26 Yet, for Hurd, neutrality (or at least impartiality) was an essential precondition for British diplomatic engagement with the war in Bosnia. At the outset of the war, Hurd had identified the Serbs as the primary aggressors, yet a year later he stated: ‘No side has a monopoly on evil . . . No one is blameless’.27 For John Nott, this was a nonsense that was fundamentally deceitful. ‘Another lie, often used in British propaganda, and stated by ministers in parliament, was that all sides were guilty of atrocities and ‘were all as bad as one another’.’28 The polar opposite of Hurd in terms of the neutrality question was Margaret Thatcher. It is certainly instructive to compare her rhetoric with that of Hurd.

Thatcher’s formative years had caused her to regard the very concept of appeasement as an absolute abomination. Cultivated neutrality was neither desirable nor natural. For Hurd, such talk was too far removed from reality to be the basis for any foreign policy. Indeed, the crux of the debates about appeasement rests with this question as to whether or not neutrality is a desirable position for policy makers to adopt in international affairs. In 2009, Hurd observed: ‘The policy of appeasement had powerful arguments in its favour. It had enjoyed a long and respectable history in the hands of Salisbury and, before him, of Castlereagh. Neville Chamberlain pursued the policy with integrity and determination.’ But, too late, Chamberlain learned that Hitler would never keep his word and ‘it is useless to appease rulers who [have] no intention of keeping their word’.30 This, however, runs contrary to the fact that Milošević, the main target of Hurd’s appeasement in the Bosnian War, rarely kept his word. What is more salient is the fact that Hurd had been successful in Bosnia. Kosovo could be dismissed as another matter altogether for two reasons: first, it occurred after Hurd and the Conservative Party had left office; and, second, Milošević had never signed any ‘piece of paper’ in which he had declared the Serb territories of Bosnia to be his ‘last’ territorial demand. Indeed, we might well ask if it is useful to seek to label Hurd an appeaser at all. Hugo Young perceptively identified the reasons why Hurd might conceivably escape the charge of appeasement by virtue of his being successful in attaining his policy ends.

As a writer of history, Hurd has repeatedly articulated a defence of appeasement – in both empirical and theoretical terms. For Hurd: ‘Peacemakers are invariably mocked until they succeed . . . [although] the peacemakers have their ration of praise; in phrases which have come down through twenty centuries and will be remembered when the arguments of today have been forgotten.’32 One might well expect Hurd, as a fellow Conservative and practitioner of a cautious Realpolitik, to make positive (albeit highly qualified) noises about Neville Chamberlain. Perhaps more surprising on this score are the words of Tony Blair in his memoirs. Blair, after all, had secured his place in history by his espousal of a morally driven foreign policy wholly at odds with talk of ‘a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing’. Blair, nevertheless, wrote: ‘A comparison to Chamberlain is one of the worst British political insults. Yet what did he do? In a world still suffering from the trauma of the Great War, a war in which millions died, including many of his close family and friends, he had grieved; and in his grief pledged to prevent another such war.’ This, for Blair, was ‘[n]ot a bad ambition; in fact, a noble one’.33 Quite why this passage was included in his memoirs is not clear (although Blair could certainly identify with Chamberlain’s self-righteous morality and his sense of mission). Most likely, Blair had simply come to appreciate the multitude of pressures, domestic and foreign, exerted on a serving prime minister.

History remembers Dwight D. Eisenhower more kindly than it does Neville Chamberlain. This is due not least to the fact that the soldier statesman is almost never regarded as an appeaser. Despite this, Eisenhower certainly understood that appeasement, in its proper definitional sense, had a place in international affairs. ‘There is, in world affairs, a steady course to be followed between an assertion of strength that is truculent and a confession of helplessness that is cowardly.’34 In this vein of reality, Eisenhower confessed to Macmillan: ‘On Berlin we have no bargaining position.’35 Macmillan himself, who took pride in being a staunch opponent of appeasement in the 1930s, had asserted in 1947 that ‘if history, and especially recent history, teaches us anything, it is that a policy of weakness and appeasement is more dangerous than a policy of straightforwardness and firmness. In feebleness and uncertainty, and not in strength and resolution, lie the seeds of war.’36 When he made that speech Macmillan was still an instinctive anti-appeaser. In 1947 this was a moral stance. Yet, the experience of office and the necessity of making policy meant that, by 1958, he adopted a very different attitude towards West Berlin. Part of the explanation here undoubtedly lies in the existence of nuclear weapons. For some the mere presence of such weapons encouraged appeasement by increasing the necessity of avoiding war.37 Harold Macmillan, the onetime officer in the Grenadier Guards,38 – was one such figure.

In today’s world many of the debates on appeasement inevitably focus upon the foreign policy of the United States. The events of 9/11 completely discredited appeasement as a policy option in US political discourse (as Munich had once done in Britain). As the rhetoric about the ‘axis of evil’ swept all before it, neoconservative commentators ignored the fact that, during the late 1980s and early 1990s, US presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton had effectively pursued a policy of appeasement towards North Korea. This aimed at inducing Pyongyang to abandon its nuclear weapons programmes. In October 1994, North Korea agreed to freeze its nuclear programme and to grant access to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors in return for certain concessions from Washington. The agreement was widely condemned in the United States by such figures as former Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and Senator John McCain (R-AZ) as an act of appeasement whose substance was ‘all carrot and no stick’.39 Although there was, in fact, an implicit threat that if North Korea did not play ball the United States could still resort to force,40 hardliners were able to make substantial political capital out of the very idea of the United States appeasing an upstart state such as North Korea. Those who had favoured a conciliatory approach despaired as, from 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney repeated assertions that ‘[w]e don’t negotiate with evil, we defeat evil’. While the United States refused to engage with ‘evil’, the North Koreans duly developed a nuclear capability.41

After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, President George W. Bush, while making war on terror, also effectively made war on appeasement. This meant that those states that failed to adopt a similar perspective to that adopted by the United States risked a serious rupture with Washington. The diminution in the willingness of many states to resort to force in the nuclear age has promoted suspicion among those with a more traditional view of the threat and use of force in international relations. And this is certainly a cause of tension in relations between the United States and Western Europe in recent years. In 2002, Walter Russell Mead, of the Council on Foreign Relations, argued: ‘Americans just don’t trust Europe’s political judgment. Appeasement is its second nature. Europeans have never met a leader – Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Qaddafi, Khomeini, Saddam Hussein – they didn’t think could be softened up by concessions.’42 Those states that deviated from the post-9/11 US line on appeasement were infamously dubbed ‘Old Europe’ by Donald Rumsfeld. These states were distinguishable from the ‘New Europe’ of the former Soviet Empire who ‘had a recent understanding of the nature of dictators, whether a Stalin, a Ceauşescu, or a Saddam Hussein’.43 Washington’s worldview resonated in these states as it did in Israel, whose own extended war against terrorism had long since imbued that state with a fear of appeasement.44

After periodic bouts of enthusiasm for the logic of appeasement stretching from Yalta to Bosnia, the ‘War on Terror’ saw Britain in the vanguard of loyal adherents to the morally absolute model of anti-appeasement. The morality underlying this conception was, however, no mere abstract concept. If the existence of nuclear weapons had provided a rationale for moderation in Cold War confrontations with Soviet Union – in order, of course, to pursue détente not appeasement45 – then matters were seen to have changed after 11 September 2001. Bush and Blair’s ‘War on Terror’ necessitated what we might term a ‘war on appeasement’, which involved the (mis)appropriation of history at every turn.46 Chamberlainite appeasement and Munich lay at the very centre of these processes, although the analogies were often flawed. As Gerhard L. Weinberg noted in 2002:

In a similar vein, Keith Robbins advised that, with regard to the past of appeasement, the only ‘lesson of Munich [is] that there should be no lessons’.48 Such aphorisms do not, however, deter policy makers from seeking the legitimacy afforded by being known to have taken the ‘lessons’ of history on board. As part of the rhetorical strategy deployed after 9/11, the US administration let it be known that the president regarded Churchill as his model.49 Echoing Kennedy’s 1962 learning process from The Guns of August, the fact that Bush had read Lynne Olson’s Troublesome Young Men was publicized.50 This was a wholly rational and logical strategy for, as Jeffery Record recently noted: ‘No historical event has exerted more influence on post–World War II U.S. presidential use-of-force decisions than the Anglo-French appeasement of Nazi Germany that led to the outbreak of World War II.’51 When the fact that Troublesome Young Men had influenced Bush became public knowledge Olson, naturally keen to further heighten the profile of her book, wrote that a comparison of Bush and Churchill was historically improbable. In Churchill’s place she proposed Neville Chamberlain as a model for Bush (referring to the latter’s lack of experience of international diplomacy and tendency to unilateralism).

Olson, no doubt, pleased Liberal opponents of Bush by mocking his attempts to strike a Churchillian pose. His legitimacy, and that of his wars, would be, by extension, undermined. And she was probably right. Alas, being right (while valued by scholars and intellectuals) has little to do with modern mass politics. The mere act of disclosing Bush’s interest in history (and thus allowing him to draw the proper conclusions from its ‘lessons’) had already done their work. Highlighting the inconsistencies in, and the misuses of, history by Bush and Blair will only convince a certain (limited) proportion of the population of the rectitude of any given point of view. Hurd was right when he asserted that wars and crises usually elicit two polar reactions in Britain: first, do nothing unless Britain’s national interests are involved; second, do something as it is the nation’s duty to alleviate suffering. Of the need to reconcile these two positions, Hurd noted:

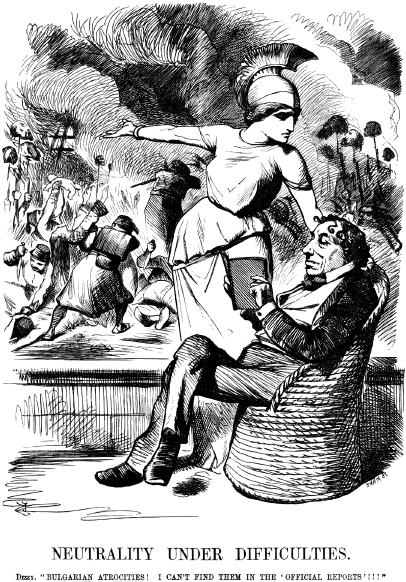

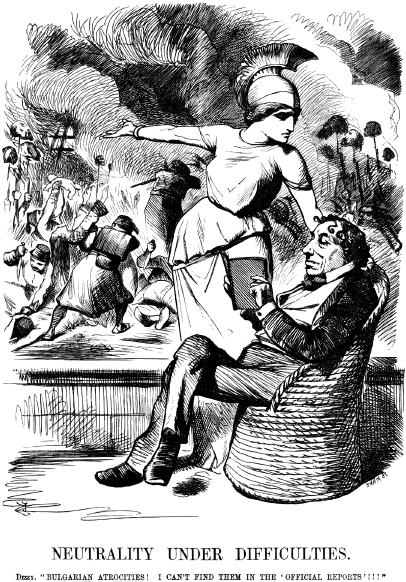

In assessments of the perpetual questions facing the makers of British foreign policy Gladstone’s worldview is always contrasted with that of Disraeli. In 1876, while Gladstone headed widespread protests over Turkish atrocities against civilians in Bosnia-Herzegovinia and Bulgaria, Prime Minister Disraeli strongly resisted calls for intervention. Disraeli dismissed Gladstone’s bestselling pamphlet The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, stating: ‘of all Bulgarian horrors [it is] perhaps the greatest’.54 For Disraeli, Gladstone’s moral impulses were a dangerous distraction. Disraeli was insistent that no British government should lose sight of the national interest: ‘What our duty is at this critical moment is to maintain the Empire of England. Nor will we ever agree to any step, though it may obtain for a moment comparative quiet and a false prosperity, that hazards the existence of that Empire.’55

ILLUSTRATION C.1 Punch, 5 August 1876. The bitter dispute that arose between William E. Gladstone and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli regarding the latter’s refusal to act against the Turkish atrocities in Bulgaria effectively defined the parameters of debates on appeasement and intervention for generations of British policy makers.

For Hurd, the policy choice represented by the respective positions of Gladstone and Disraeli was neither new nor likely to disappear anytime soon. The two traditions in British foreign policy were exemplified by Lord Castlereagh’s pragmatic, conciliatory foreign policy and George Canning’s more muscular, interventionist one.56 The necessity of retaining both traditions as a policy option continues, not least as they are rendered timeless by their utility at given times and places. One might usefully recall that, when Alexander I of Russia complained of ‘those who have betrayed the cause of Europe’, Talleyrand asserted: ‘that, Sire, is a question of dates’.57 In this vein, conciliatory approach to the Soviets, deemed unacceptable in the late 1940s, was tolerated in the mid-1970s precisely as ‘a question of dates’. After 1945, in order to rehabilitate diplomacy, while repudiating the mindset that had led to Munich, the West had embraced the policy of ‘Containment’.58 By its ability to introduce restraint into foreign policy, without signalling weakness to a watchful international community, this term was surely one of most useful euphemisms in diplomatic history.59 Today, any number of commentators remain willing to denounce the malign influence of appeasement upon the foreign policies of the West.60 In Britain, the 2013 debate on whether or not to intervene in the Syrian civil war once more saw the invocation of the era of appeasement.61 The perceived irresolution of the West over Syria led Israel’s economics and trade minister, Naftali Bennett, to observe: ‘The international stuttering and hesitancy on Syria just proves once more that Israel cannot count on anyone but itself. From Munich 1938 to Damascus 2013 nothing has changed. This is the lesson we ought to learn from the events in Syria.’62 The shadow of Munich thus remains a long one, continuing to influence the foreign policy of any number of states. Unsurprisingly, this is especially so in the country that is the most famous past victim of appeasement (the Czech Republic),63 and in the state that fears it most in the present (Israel). During a 2012 debate between presidential candidates in the Czech Republic, Miloš Zeman asserted that:

Zeman, the Social Democrat leader and eventual winner of the presidential election, asserted that for these reasons he would support an Israeli pre-emptive attack on Iran. This would require courage and the Czech Republic would alienate Israel’s enemies, but it would be the right thing to do.64 Such moral absolutism, naturally, rests on what is right while too often neglecting to consider what the best course of action is. In his memoirs, Edward Heath, a staunch opponent of the appeasement of Hitler who was later denounced as an appeaser for his insistence upon the necessity of keeping a diplomatic channel open to Saddam Hussein in 1990, despaired as to the estrangement of the basic tenets of diplomacy from their real meaning.

This is nothing less than a recognition that foreign policy has, on occasion, to be used in order to seek to address grievances and not just for the purpose of defending the status quo. In 1961, Walter Lippmann simply, but correctly, observed that ‘you can’t decide . . . questions of life and death for the world by epithets like appeasement.’66 Years earlier, E. H. Carr had written that ‘peaceful change can only be achieved through a compromise between the utopian conception of a common feeling of right and the realist conception of a mechanical adjustment to a changed equilibrium of forces. That is why a successful foreign policy must oscillate between the apparently opposite poles of force and appeasement.’67 In rejecting such an elementary truth, the rhetoric of postwar anti-appeasement often caused policy makers to embrace morally-driven absolutist positions in international affairs. The employment of such a policy-making formula always renders a number of policy options permanently unavailable. In a dangerous world such an approach will, sooner or later, have tragic consequences.