10.

DAMASCUS,

16 SEPTEMBER–

11 NOVEMBER 1918

THE ‘ROAD TO DAMASCUS’ EXPERIENCE

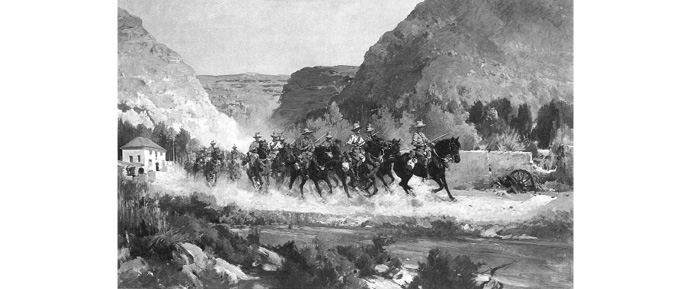

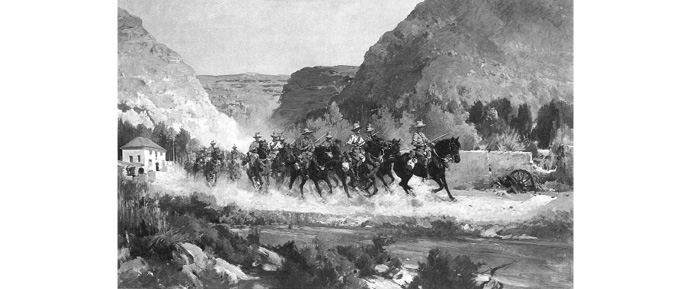

As Damascus was surrounded by rugged hills, the Light Horse had to approach through valleys, risking ambush as they headed for this make-or-break battle where they feared the Turks would mount a last-ditch stand. ‘Damascus Incident’ painted by H. Septimus Power. (AWM ART03647)

My dear Chauvel, I do congratulate you on your ably conducted and historic ride to Damascus, and on all the rest of the performances of the Cavalry in this epoch-making victory. You have made history with a vengeance and your performance will be talked about and quoted long after many more bloody battles in France will have been almost forgotten … and it was the Cavalry who put the lid on the Turks’ aspirations forever!

.jpg)

With his Egyptian Expeditionary Forces advancing north on both sides of the Jordan, supported by Lawrence of Arabia and his Arab Army on the eastern side of the river, Allenby was closing in on the last Turkish stronghold of Damascus by late September 1918.

BACKGROUND TO THE BATTLE

Having been defeated at the battles of Es Salt and Amman, Allenby bided his time, falling back and regrouping during the long, hot, dusty summer before setting out on the road to Damascus.

It was just as well because, coincidentally, given the well-known biblical precedent of Saint Paul on the road to Damascus, where he was inspired to convert to Christianity, by the time Allenby’s forces drove the Turks north, captured all the enemy towns along the way and approached their long-awaited destination, there would be plenty of unexpected and historic experiences for the competing players on the road to Damascus. In fact, it was such a race to this finishing post that some of the leading players experienced upsets almost as dramatic as those biblical precedents.

The contestants included Lawrence and his Arab Army, which had led the powerful Arab revolt and dreamed of reaching Damascus first, liberating the city from the Ottomans, installing Feisal as the king, and establishing the long-awaited Arab rule promised by the British. But Lawrence and the Arabs were upstaged by both Australian and British forces. Allenby and his dominant British forces were meant to arrive first in Damascus to claim control for Britain, with Allenby planning a symbolic entry like his conquering walk into Jerusalem; but a troop of carefree Australians beat their British masters to Damascus. The irreverent Australian Light Horse 10th Regiment — whose men had ridden so far and so fast ahead of all other forces — could not have cared less about the political protocol of symbolic arrivals. They rode in first because they just happened to get there first, and it suited them to take a short cut through the city — even if it did upset their superiors’ best-laid plans.

But of course those who suffered the worst ‘experience’ were the Turks and their German leaders, who were defeated after their last-ditch stand at their final stronghold. They were driven out of town, still being led by Britain’s old Gallipoli foe, Mustafa Kemal.

Another ‘experience’ was that of the Arabs and other citizens living in Damascus. They now had to switch from their centuries-old colonial ruler — the Ottoman Empire — to the occupying forces led by the British.

All these events followed that most famous experience on the road to Damascus for the opponent of Jesus Christ, Paul aka Saul, an event familiar to the Christians among the British and Australian forces, especially Allenby and Chauvel. For according to the biblical story in the Book of Acts, Chapter 9, verses 3 to 6 (King James version), this was where he had his conversion:

‘And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven: And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? And he said, Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks. And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? And the Lord said unto him, Arise, and go into the city, and it shall be told thee what thou must do’.

Saul later explained that the voice of Jesus then commissioned him to become a ‘messenger to the Gentiles’, a complete change for Saul, who had always been a passionate Gentile-hating Pharisee, and believed the Jews alone had the place of honour in God’s eyes. But he felt compelled, as Jesus ordered him, ‘to turn [the Gentiles] from darkness to light and from the power of Satan unto God, that they may receive forgiveness of sins, and inheritance among them which are sanctified by faith that is in me’.

As seen previously, Allenby’s ‘Christian soldiers’ had noted in their diaries or letters the religious significance of many of the towns and villages they captured en route to Damascus — especially Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Jericho. Before Damascus, though, they had their sights on Nazareth, which was where the archangel Gabriel visited Mary, telling her she would become the mother of the saviour, and also where that saviour would grow up. As Idriess wrote earlier: ‘At times we felt we were riding through the pages of the bible’. In fact, when the devout Allenby captured Megiddo, he announced the time had come to start the final battle. This may have been because Megiddo used to be known as Armageddon, and that was where Saint John had predicted, in the Book of Revelation, that the final battle would be fought before the return of Christ. Allenby knew capturing Damascus would not shape the future of the world, but this lifelong Christian still believed it would be the end of the Ottoman Empire, which had shaped this part of the world for centuries.

To Christian Light Horsemen, Damascus was best known for the biblical story of Paul’s ‘Road to Damascus experience’ where this rebellious religious activist was converted to Christianity.

By Megiddo, Allenby was certainly ready for the final push. After that four-month summer break, he had come up with a clever plan for the advance and tactics for tricking the Turks, which he was keen to put in place. By September 1918, Allenby had reorganised his troops and had the biggest force yet. He boasted 140,000 men in his three army corps, 57,000 rifles, 12,000 sabres, and 540 guns. He was determined to defeat the weakened Turks once and for all. Bean said Allenby knew from reliable intelligence that their total force was only 103,500, and that all three Turkish armies were ‘in very bad shape’ — the Fifth Army, Mustafa Kemal’s Seventh, and also the Eighth Army. Yet Allenby estimated the enemy only had 26,000 rifles, 3,000 sabres, and 370 guns. To make matters worse, Turks were deserting in increasing numbers, averaging more than 50 a week.

Charles Bean reported that apart from reconstructing his British divisions, Allenby also restructured the Australian Mounted Division, turning it into a purely Australian force. Within this he created the 5th Light Horse Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General George Macarthur-Onslow, made up of two extra Light Horse Regiments, the 14th and 15th, created with Australians from the Imperial Camel Brigade, which Allenby had disbanded.

As he wanted these regiments to fight as cavalry, Allenby also issued swords to the troopers in this new brigade. On paper, the Turks did not stand a chance because the experienced and successful Chauvel now commanded four divisions — the largest cavalry force in history. In August, the 4th Light Horse Regiment (which had charged at Beersheba) had been issued with swords and trained in traditional cavalry tactics in preparation for the next offensive against the Turks.

Allenby and his men expected great things from this advance on Damascus.

Yet weather could undermine even this great force, so timing was critical. That is why Allenby had decided that he must mount this final offensive north in September, and capture Damascus in early October, before the rains came in November and December. This was an ambitious plan, as his forces were still nearly 100 kilometres south of Damascus, with their frontline stretching across the Holy Land south of the Sea of Galilee from Haifa on the coast across to the east just south of Deraa (the vital railway junction town used by the enemy to move troops by train from battle to battle).

16 September

As Allenby knew that Liman von Sanders, who had defeated the British at Gallipoli, also saw Damascus as a last stand, he tricked the Turks into thinking he would advance from the eastern side of the Jordan Valley inland rather than from the coast. The Turks were so convinced that when a devout Muslim Indian sergeant deserted the British ranks and told Liman von Sanders the truth, the German general disbelieved him, claiming he was a plant sent to trick them. Mustafa Kemal, by contrast, did believe the Indian but was overruled by Liman von Sanders. Kemal, who detested Liman von Sanders, had learnt his lesson from the tricky pretence the British and Australians organised so skilfully at Gallipoli to conceal their nocturnal retreat — once bitten, he was twice shy.

By the final advance towards Damascus, the Royal Flying Corps and the 1st Australian Squadron, with its ace pilots, were easily defeating any German bombers who dared to venture into their airspace.

To aid his deception, Allenby ordered the creation of a make-believe camp headquarters to be maintained inland, with fake horses; he also set up his fake headquarters in Jerusalem at a fancy hotel. Chauvel created empty tent camps to pretend his HQ was based elsewhere, 80 kilometres away at Talat el Dumm, in another valley. Having succeeded in tricking the Turks for weeks before the evacuation at Gallipoli (where they had rigged up self-firing unattended rifles in trenches), Chauvel and his Australian troopers had good experience in deception, using fake horses, unattended campfires, electric lights, and gunshots in what was really a ‘ghost camp’. Engineers also dragged big sleds around to stir up lots of dust that looked, from a distance, like troop movements. The Turks were certainly taken in, because they reported at this time ‘some regrouping of cavalry units only on the coast’ but otherwise ‘nothing unusual to report’, Bean wrote.

Meanwhile, in the dead of the darkest night, the real moves were made for the start of the attack on Damascus. Allenby ordered Chauvel to move his real headquarters from the inland Jericho road to the coast in readiness for the last great offensive. The air force, which by then had gained superiority over the German air force, was mapping the Turkish positions around Damascus with little opposition. The 1st Australian Squadron was by then described as ‘ the finest that ever took to the air’ by the British air force commander, Air Vice Marshall Sir John Salmond.

17 September

Allenby ordered the British and Anzac forces to advance north just inside the coast on the western side of the Holy Land. He paid a visit to Chauvel to wish him luck.

Chauvel certainly hoped fortune would favour his attempts this time to defeat Kemal, who had forced him off the beach at Gallipoli and who, as commander of the Turkish Seventh Army, now blocked Chauvel’s path to Damascus. Luckily, Chauvel’s other Gallipoli nemesis, Liman von Sanders, had refused Kemal’s request to unify all three Turkish armies in order to create a larger force to stop Allenby’s advancing men. This refusal by his German superior infuriated the Gallipoli hero and further undermined the solidarity between the Germans and Turks.

Always the diplomat, as Allenby’s forces advanced further north, the Desert Column commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Chauvel, negotiated peace agreements with local Arab chiefs.

Based over near the coast in the village of Sarona, just north of Jaffa, with his troopers at Jaffa and Ludd, Chauvel made his plans. He would first capture Nazareth and El Afule to the north-east, both communication centres and headquarters. Liman von Sanders was based in Nazareth.

Allenby also commissioned Lawrence to continue fighting further east, inland, doing the groundwork for the forthcoming advance by blowing up important railway lines and stations on the far eastern side of the Allied advance — hopefully putting the important rail junction town of Deraa out of action.

19 September

Allenby now ordered the great advance north using all his forces, both in the air and on the ground. It would be the last major offensive — its objective, Damascus.

The assault started with a massive bombardment from the air and the ground to help Allenby’s infantry attack the Turkish line at its coastal end as the infantry advanced along the coast. His infantry immediately broke though Turkish defences on the coast, capturing Tul Keram and heading north.

Chauvel’s Desert Mounted Corps rode north just inland of the coast from Jaffa towards Jenin. Meanwhile, two Indian cavalry divisions advanced north — minus that one devout Muslim sergeant who had deserted a few days earlier. Soon, the mounted forces penetrated deep into the Turkish rear areas, severing roads, railways, and communications links.

The Turkish resistance was collapsing, as the demoralised troops would rather surrender than fight for these last bastions of the old Ottoman Empire. Allenby’s forces seemed to be everywhere. The British infantry led by Chetwode and Bulfin, along with Chauvel’s mounted men, advanced on El Afule, conquering this village and taking 1,500 prisoners. Chauvel’s men rode north, capturing Nazareth, but not before Liman von Sanders had managed to escape in a Mercedes wearing his pyjamas, much to the disappointment of Chauvel. They had also captured the little town of Jenin en route with 3,000 German and Turkish prisoners, as well as Megiddo. It was becoming a rout.

Meanwhile, further east inland Lawrence blew up a four-arched bridge at Mafraq, in a classic lightning strike that was very successful, apart from the fact that the Rolls Royce he was travelling in (instead of on his usual camel) broke down temporarily as he retreated from angry Turks, who threatened to shoot him until his driver got the vehicle going again. But at last this deadly Arab Army was really part of the team, as Lawrence said: ‘The Arab movement had lived as a wild-man show, with its means as small as its duties and prospects. Now Allenby counted it as a sensible part of his scheme; and the responsibility upon us of doing better than we wished, knowing that forfeit for our failure would necessarily be part-paid in his soldiers’ lives, removed it terrifyingly further from the sphere of joyous adventure’.

Next, Lawrence and his Arab Army raiding party bravely attacked the biggest railway terminus south of Damascus itself, Deraa, and with his increasingly skilled demolition experts successfully blew up the railway tracks, to the south then to the north. They also cut off the telephone lines, thereby isolating this important Turkish stronghold, so the Turks could not use Deraa for transporting either troops or supplies. They went on to disable all the rail and communications equipment at nearby Mezerib and then at Nasib. In most of these hit-and-run raids, Lawrence was lucky to escape, because the Turks defended railway lines and junctions from within strong fortifications, and their German comrades bombed Lawrence and his fearless raiders from the skies above.

20 September

Brigadier-General Wilson’s 3rd Light Horse Brigade took Jenin, capturing 2,000 Turks and Germans — most happy to surrender. Later on the night of the 20th, the 10th Regiment of Wilson’s 3rd Brigade also captured another 3,000 Turks retreating from Jenin. More Turks kept turning up overnight, and by first light on 21 September there were 8,000 prisoners.

The 4th Cavalry Division captured Beisan, then the 5th Cavalry Division captured Haifa on the coast; the 5th Light Horse destroyed the Samaria railway.

Finally, as Bean reported, after infantry action, the Australian Mounted Division also advanced in greater numbers than before from the Jordan Valley towards the previously elusive Es Salt and Amman, which were by then poorly defended. This time, victory would be easier, as rather than isolated battles, the move against Es Salt and Amman was part of a wider cavalry thrust towards Damascus itself by a well-coordinated and larger moving frontline.

Whenever the casual Australians rode confidently into ancient towns like Nablus, the locals stopped in their tracks and stared in amazement at these slouch-hatted bronzed bushmen, so scantily clad compared to them.

22 September

And so it was that once his forces had captured the old Ottoman town of Megiddo, aka Armageddon, Allenby had his first ‘road to Damascus’ experience. It suddenly dawned on him that the road ahead was clear and he could race on to Damascus. So he convened a conference with Chauvel, pulled out his maps, and announced he had decided to continue his advance right through to Damascus. It was a bold decision — with the remnants of three Turkish armies blocking his path — but he believed fortune favoured the bold.

After all, this juggernaut had already rolled over the plain of Esdraelon, had taken 13,000 prisoners, conquered the village of Jenin, won the hard-fought Battle of Semakh, and also secured the villages of Kuneitra and Sasa — so he was keen to maintain the momentum.

Allenby ordered Chauvel to advance further with the Australian Mounted Division, and with the 5th Cavalry Division following on, ordered them all to advance west of Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee). He ordered the 4th Cavalry to advance to the east of the lake, where Lawrence was expected to follow, with his Arabs also riding up inland east of the lake, with a greater force than ever, thanks to Allenby’s generosity. Said Lawrence, ‘Allenby had now put three hundred thousand pounds into my independent credit account to cover personnel and equipment. With us now journeyed at least two thousand Sirhan camels, carrying our ammunition and food’.

When he finally led his conquering Light Horse Regiments into Damascus, Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Chauvel put on the biggest show of strength he could, to demonstrate who now controlled Damascus.

Most of the Light Horsemen were happy to push on, especially after the victory at Jenin, where they had discovered hundreds of bottles of sweet sparkling German wine. As ‘the big brass’ had made the mistake of assigning a couple of troopers to guard this treasure trove, it was not surprising that many of their fellow troopers soon had relaxed, happy grins on their faces and were ready and willing for anything.

23 September

So the grand advance continued. By now, even the Australian troopers among Chauvel’s coastal forces hoped to defeat the Turkish Seventh Army, still blocking their progress north, because they wanted to get back at Mustafa Kemal, whose forces had slaughtered so many of their mates at The Nek and other battles at Gallipoli. British infantry soldiers felt the same — some of them had also been defeated by the Turks at the Dardanelles in the bloodbath at Cape Helles.

Allenby’s wide moving frontline was now much more supported in the air by successful pilots like Captain Ross Smith in his magnificent — but one and only — Handley-Page bomber. He was one of many fearless and skilled Australian pilots flying for the Royal Australian Flying Squadron, including Captain Peters and his navigator-gunner James Traill (who had delivered the carrier pigeons to Lawrence that the Arab leader had eaten), and who by now had established great track records shooting German aircraft who opposed them.

Lawrence recounted how he, Smith, and another pilot were sitting down to a hot breakfast of eggs, sausages, and coffee at Lawrence’s camp when suddenly two German aircraft appeared in the sky, heading for the Arab Army with bombs. Lawrence wrote: ‘Our Australians scrambled wildly to the yet hot machines and started them in a moment. Ross Smith with his observer leapt into one and climbed like a cat up into the sky.’ The planes headed straight for the oncoming enemy aircraft and engaged them with their machine guns. Lawrence continued: ‘Ross Smith fastened on the big one and after five minutes of sharp machine gun rattles, the German dived towards the railway line. As it flashed behind the low ridge there broke out a pennon of smoke and from its falling place a soft dark cloud. An “Ah” came from the Arabs about us’. Both enemy aircraft were destroyed. When the Australians landed, Lawrence wrote, Smith ‘jumped gaily out of his machine swearing that the Arab front was the best place. Our sausages were still hot; we ate them and drank tea’.

Australia’s Palestine war correspondent, Henry Gullett, confirmed that story, explaining why the Arabs were so appreciative: ‘By now the Australians were dominating the air aided by the most unlikely allies as Australian airman [sic] have been engaged in a fascinating enterprise among the Arab allies. These pilots lived with the Arabs in their camps taking off for much effective bombing to far flung places that could only be reached from outlying Arab camps. One day they shot down two Hun planes among the Arabs who raced forward frantic with delight and excitement’. As Arabs loved looting the enemy, Gullett said, ‘this adventure had a profound effect on our Arab Allies and spurred them on to increase their fine efforts’.

This spur was important, as Allenby was depending on Lawrence and his Arab Army to continue moving north on the eastern side of the advance, and to blow up more rail lines to stop any Turkish troop reinforcements. Lawrence said Allenby had nothing to worry about, because ‘Allenby’s smile had given us Staff, supply officers, an intelligence branch, and ordinance expert, a shipping expert and everything we needed’.

Pilots like Ross Smith provided so much valuable intelligence — including that many Turkish troops were now retreating — that these airmen were having more and more influence on the outcome of battle.

Just after Smith and other pilots flew Lawrence back to his camp south of Umm Tayeh, they were able to stop yet another German aircraft attacking that camp.

Later, Captain Peters flew up from Lawrence’s camp to engage another German plane with his navigator, James Traill. Peters and Traill not only chased the enemy plane back to Deraa, but, when the German plane landed, set it alight with their deadly fire. Then the sharp-eyed marksman Traill shot the two airmen trying to escape.

But Lawrence was so angry that the German aircraft were bombing his Arab camps with raid after raid that he asked Captain Ross Smith and his fellow Australian pilots to get rid of them. Smith, who always relished a challenge, went off to the coast to collect a bigger plane — a Handley-Page bomber. In company with a couple of Bristols, Smith took off from Lawrence’s camp and flew towards the German airfield at Deraa, ready to shoot any enemy planes out of the sky. On arrival, they shot to pieces or bombed every German plane on the ground at the Deraa aerodrome, dropping nearly a tonne of bombs and setting fire to both planes and hangars — thus removing an obstacle to the British advance towards Damascus.

24 September

Over in the east, Allenby’s forces had also finally captured Es Salt and Amman, when they defeated the remnants of the defending Turks there as part of the relentless advance north.

This third-time-lucky victory was a combined effort, as Henry Gullett explained: ‘Simultaneously while Chaytor’s New Zealand Division were overrunning Es Salt on the east of the Jordan River where they captured 350 prisoners, the Australian Light Horse were also moving upon the Hedjaz railway after an all night march. The Light Horse then straddled the railway towards Damascus and they captured a complete train under steam and blocked the road … the enemy fought resolutely and the struggle was the sharpest the cavalry experienced so far. Severe hand to hand fighting took place before the enemy, made up largely of Germans and strongly equipped with machine guns, was overcome’.

When Major-General Chaytor’s forces, advancing from the Jordan Valley along with the Australian Mounted Division, had finally overrun the elusive Amman, they captured 2,500 prisoners from the retreating Turkish Fourth Army. The Turks were now on the run — in fact, Bean reported that 5,000 of the enemy were now cut off south of Amman and trying to head north, dodging Allenby’s forces.

By the end of the Palestine campaign, the commanding officers (but never the envious troopers) were using motor vehicles whenever they could because speed had become so critical, especially with events like the race to be first to Damascus.

Allenby had been very wise to bide his time, as Turkish resistance had moved north and weakened during that waiting time. It was something of an anti-climax; after securing Es Salt and the Hedjaz railway, Allenby’s forces easily captured Amman against demoralised and retreating Turkish forces. As Gullett wrote: ‘The Light Horsemen were never more eager to win’.

‘The enemy casualties included 60 killed and thirty wounded, prisoners included 22 officers and 350 other ranks — nearly half of whom were Germans’, Gullett continued. ‘But by then the present position of the Turks’ whole front line was desperate in the extreme.’

It had taken a long time, many months, to capture the stubborn and well-defended heights of Es Salt and Amman but it was worth it — Chaytor’s forces captured 10,300 prisoners and 57 guns at a cost of just 139 casualties.

25 September

Allenby had ordered the advance against Lake Tiberias because he knew Liman von Sanders was using the lake, about 80 kilometres south of Damascus, as a natural buffer, with enemy defences entrenched at the southern and western ends. Now Allenby ordered Chauvel to send his experienced 4th Light Horse Brigade straight to the southern end of the lake to expel the enemy defending it.

At dawn on 25 September, Chauvel’s 11th Light Horse Regiment successfully charged the southern end of the lake from the east. Although half their horses were hit by enemy fire, after a series of fierce battles the 11th Regiment overcame the defenders, killing 100 (mostly Germans) and capturing hundreds of Turkish prisoners. A little later, Chauvel’s 12th Regiment, supported by the 4th Machine Gun Squadron, attacked the enemy’s defences at the western end of the lake. After fierce fighting for a few hours, the 12th also succeeded in displacing the enemy defenders there. So Liman von Sanders’ natural defence of the lake suddenly evaporated, removing another obstacle for the advance on Damascus.

28 September

Chauvel’s Australian Mounted Division, heading north on the west of the lake, fought against a tough rearguard of German machine-gunners and Turks were forced further to the north.

The 5th Light Horse Brigade’s commander, now Lieutenant-Colonel Donald C. Cameron, reported a big turning point to Allenby. The Turkish commander, who was cut off from his northern comrades and retreating from south of Amman, offered to surrender! The Turkish leader said they would throw down their arms on one condition: that the Australians would protect these routed and exhausted troops from marauding Arabs threatening to kill them. When 2nd Brigade Commander, Brigadier-General Ryrie, arrived with his 7th Regiment, he and Cameron agreed to the Turks’ request because the Arabs — from the Beni Sakr tribe near Ziza Station — were not part of Lawrence’s loyal followers, but were instead a rebellious tribe who were circling around, shouting threats and firing their rifles menacingly into the air.

Although they had established temporary headquarters in the field, the increasingly harassed Turks had to abandon these as Allenby’s forces closed in on Damascus, often fleeing so quickly that they left their tents behind.

So the Australians recruited the newly surrendered Turks into their ranks before nightfall; along with Ryrie and Cameron’s forces, the Turks then defended the position from the Arabs, who continued to threaten the now-united Turkish and Australian force. Shoulder to shoulder, the Turks and Australians fought together throughout the night. Next morning, when a New Zealand brigade arrived reinforcing the Allies and scaring off the hostile Arabs, the Turks then meekly handed over their weapons. They joined the swelling number of Turkish prisoners. But for one night they fought alongside each other, making a mockery of their years of mutual hostility. These friendly Turks then joined Chaytor’s large groups of prisoners — then more than 10,000, all captured on this initial drive towards Damascus.

30 September

Allenby’s forces, led by the Desert Mounted Corps, were closing in on Damascus. It was only a matter of days now, and different men were hoping to cross the finishing line first.

Not that the fight was over yet. Even as the German and Turkish forces retreated towards Damascus, tails between their legs, they suddenly turned around and took a stand at Kaukab, on a ridge with a higher vantage point, against William Grant’s 4th Brigade chasing them. But using their increasing momentum under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Murray Bourchier, the 4th and 12th Light Horse Regiments, which had fought together so well at Beersheba, charged the Turkish frontline and overcame their resistance.

At the same time, the 5th Brigade rode rapidly north to the west of Damascus to encircle and cut off the Turks fighting at Kaukab, who surrendered knowing they could neither escape nor defeat the Australians, who were by then reinforced by French cavalry. Kaukab, by the way, is said to be the exact spot on the road to Damascus where Saul aka Saint Paul converted to Christianity.

By now, with Damascus in sight, it was on for young and old. The 5th Brigade positioned itself on top of the steep Barada Gorge, and, from these rocky heights, shot at Turks fleeing north. When Wilson’s 3rd Brigade joined them, the retreating Turks, by now evacuating Damascus in droves, did not stand a chance. With frightened Turks fleeing left, right, and centre, Damascus had all but fallen.

Everybody wanted to be first into Damascus — the finishing line. So the rivalry intensified between all attacking forces: the British, Lawrence, and the Anzacs. Even different Light Horse brigades and regiments were talking competitively about who would be first to ride into this almost mythical capital city of the desert. This was the end point of a long series of battles that had started with the Anzac Mounted Division’s great breakthrough at Romani in August 1916.

It was very important at the highest level, because whoever entered first could claim victory and then assert control of Damascus and Syria. As the commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, Allenby had given strict orders that nobody was allowed to enter Damascus without his permission.

Everybody had different expectations, official and secret.

Lawrence wanted to be first with his Arab Army to install Feisal as king; in fact, he had already smuggled in flags to be hoisted on key buildings to proclaim Feisal’s new possession. As Lawrence confirmed in his post-war book Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926), the British ‘promised to the Arabs, or rather to an unauthorized committee of seven Gothamites in Cairo, that the Arabs should keep, for their own, the territory they conquered from Turkey in the war. And that glad news had circulated throughout Syria’.

But the British and French had also created that secret and more powerful Sykes-Picot Agreement sabotaging that promise. Signed in May 1916, it proclaimed that all territory conquered would be divided between the British and French superpowers. Their agreement, with a map featuring different coloured regions (blue for France and red for Britain), awarded the coast of Syria (which became Lebanon) to France, and Iraq (both the central Baghdad region and the Basra region in the south) to Britain. The French would also control the north of Syria, Iraq, and Jordan, and the British the south, but with an Arab chief allowed to manage affairs under the colonial powers. Palestine was awarded to international control, but with the British becoming the dominant player. There was nothing left for the Arabs to control.

The British sought as much control as they could and planned to either govern the lands they conquered or to install puppet governments to do so for them; especially where explorers discovered oil, in places like Mosul.

Although the stakes were very high for the three main players — the British, French, and Lawrence — the Australians really just wanted the thrill, honour, and glory of being first.

But, in the end, it was a case of first come, first served. On 30 September, the eve of the planned event, the Australians were well out in front, ahead of both Lawrence and the British.

In fact, any Australian unit from the Desert Mounted Corps could have been first. The 5th Brigade, now commanded again by Brigadier-General Macarthur-Onslow, took the lead initially, racing along the road to Damascus, but was then ordered to go up into the hills on the road towards Beirut. Even though Macarthur-Onslow wrote that ‘All ranks were greatly elated at the prospect of being the first troops to enter DAMASCUS!’, the troops were ordered to bivouac high in the Barada (Abana) Gorge above the Beirut Road and railway line (full of fleeing refugees) to capture or shoot retreating Turks. Lieutenant-Colonel Bourchier’s 4th regiment (with Cameron’s 12th Regiment, which had charged at Beersheba) was also eager to be first, but was diverted with other duties. Finally, Wilson’s 3rd Brigade hoped to be first, but at the last minute were ordered to wait in the hills closer to Damascus, then to send their 10th Regiment (which had fought at The Nek) ahead to the north of Damascus and cut off Turkish troops escaping on the road to Homs.

Britain’s 5th Cavalry Division, commanded by General Henry MacAndrew, approached Damascus from Kuneitra as far as it could, competing with the Yeomanry Mounted forces commanded by General Barrow, but they were still 21 kilometres away.

Lawrence and his Arab Army were mustard-keen and rode though the night, hoping to be first and to liberate their treasured city, as a first step to establishing the free Arab nation state they had been promised. They were well behind the leading Australians, however, and although Lawrence arrived overnight and set up camp near Damascus, he made the mistake of getting up too late in the morning.

1 October: Enter the Australians — then Lawrence

The highly symbolic entry into Damascus became a fiasco. It was important, because traditionally the first conquerors to enter could take control in their own name. Although Britain’s top brass, General Allenby (who had earned this honour), wanted the Australians to wait for the British to enter Damascus first, and Lawrence and his Arab Army (who had also earned this honour) wanted the British and the Australians to wait for the Arab Army to enter first, a bunch of Australians mucked the whole thing up by just cruising in unofficially, unannounced and by mistake.

Having won so many battles in the Palestine campaign, the Australian Light Horsemen had become a bit of a legend by the time they captured Damascus — even if some of them seemed to know it, according to artist David Barker.

4–5am

The Australians who had crawled out of their blanket rolls and saddled up at 4am were the troopers of the 10th Regiment, who had just been ordered to get up early and stop any Turks escaping along the Homs road to Aleppo, north of Damascus (including their old foe Mustafa Kemal, believed to be in Damascus). But as they could not work out how to find that road, they trotted into Damascus to ask directions! So the first into Damascus — and for purely practical reasons — were the battle-hardened troopers of the 10th Regiment. And according to Henry Gullett, these Australian troopers riding towards this holy grail could not have been less official or appropriate as conquering heroes: ‘Unshaven and dusty, thin from the ordeal of the Jordan and with eyes bloodshot from lack of sleep they rode with the bursting excitement of a throng of schoolboys … exuberant horsemen … some with their swords flashing in the early sunrise’.

As Bean also reported, once the 3rd Brigade commander Wilson got the orders from above, during the night of 30 September, he sent his 10th Light Horse Regiment to find and block off that road to Aleppo. So, as Bean continued, these unassuming Australians were the first to enter the long-desired city of Damascus at 5am on 1 October — only because they were looking for the way to the Homs road.

After being ordered to block escaping Turks, Wilson, who did not have a good map of Damascus or the area, reckoned the easier route to the road to Homs was not over rugged hills but straight through Damascus — so he sensibly got permission to ‘pass through’ the city. It would be the quickest way, though more dangerous, as thousands of German and Turkish troops could still be inside Damascus. Even so, Wilson thought his men would get through the narrow streets of the enemy stronghold if they galloped as fast as they always did.

‘Believing that Damascus was still in Turkish hands’, Bean wrote in his official history, ‘the 10th Regiment headed by the brigade scouts and Major Arthur Olden (from Ballarat) — after making its way through the terrible debris in the Abana Gorge (littered with Turkish corpses) reached an open road running alongside the Abana River, which was empty. So they spurred on their horses from a walk to a trot as they saw before them shafts of sunlight bathing the minarets of Damascus with the early dawn light also shimmering on the exotic gardens of the city. Soon as the sun rose further they could see the bright city shining in all its glory like some mythical treasure — and so they broke from a canter into a gallop (leaving a cloud of dust behind them) and stormed into the great and ancient city of 250,000 souls’.

Nevertheless, even though they were just looking for locals to give them directions, the men of the triumphant 10th Regiment were now greeted as conquering heroes.

The locals certainly all stepped back for them — the noise of their horses’ hooves on the cobbled streets would have been so dramatic, especially echoing from the ancient buildings either side as this rising, thunderous roar got closer and closer.

It would also have been a spectacular sight. The men were brandishing swords that gleamed in the sunlight. Bean wrote: ‘They were greeted by a fusillade of shot but mainly from excited Arabs firing into the air in friendly demonstration.’

6am

Soon they reached the centre of Damascus and found a crowd at the Serai — the central civil administration building. Here, the bemused 10th Regiment reined in their horses, sleepy-headed troopers rested in their saddles, some with heads drooping from the early start and others looking around wide eyed at the odd assortment of locals gathering around them. Major Olden and Major Timperley dismounted, pulling their revolvers out of their holsters, and walked right into the building, which was full of robed Arabs.

This was a noisy and excited gathering of Arab notables, who had already taken control of the city from the Turkish administration. When the civil governor stepped forward, the 10th Regiment leader, Arthur Olden, warned him that Chauvel’s Mounted Desert Column now surrounded Damascus with thousands of troops. Suitably impressed, the governor quickly wrote an assurance promising peace and safe conduct for Olden’s troops on their mission to ride through the city en route to the road to Homs. The governor even provided a guide for the ‘liberating’ Australians.

6.30am

Olden accepted the surrender note and then sanctioned Emir Said as governor, taking the Arab’s word for the fact that he was now the official ruler of Damascus.

6.45am

When Olden and Timperley emerged back into the sunlight, clutching this document guaranteeing safe passage, they were amazed to see hundreds of cheering Arabs surrounding the troopers sitting astride their horses. The grateful Arabs were even feeding grapes, peaches, and sweet cakes to the astonished horses and fastening colourful flowers to their bridles!

Bean says that ‘It was only with great difficulty that the Australians disengaged themselves from the Arab welcome’. But they were there on another mission. In fact, according to the Regimental Diary, one increasingly impatient Light Horseman called out in a broad outback accent to the Arabs mobbing their horse, ‘Could you just get out of the bloody way, mate, we’re trying to find our way to that blooming Homs Road’.

7am

Eventually, having obtained their guide — an Armenian, Zeki Bey — to the Homs road, by 7am the 10th Regiment (having made history on the side) ‘were soon clear of the cheering shooting crowd’, the official correspondent Bean concluded.

Later, the 10th Regiment made more history: they fired the last shots in the Palestine campaign when they reached Khan Ayash, 30 kilometres out of Damascus. When ordered to attack the enemy, one of their officers, Colonel Daly, led a mounted charge that not only defeated the Turkish troops but also — for the first time in any Australian Light Horse mounted charge — snatched and captured an enemy flag. And this was also the last Light Horse engagement in Palestine.

Meanwhile, Lawrence woke up in his camp 25 kilometres south of Damascus, slowly shaved, had breakfast, and got dressed in his best flowing robes, determined to make a big impression for his grand entry into the city he had been dreaming about for years. He wore these robes, he said, because, ‘The Arabs never had to ask who I was, for my clothes and appearance were peculiar in the desert. I always wore the pure whitest silk, with a gold and crimson Meccan headrope, and gold dagger. By so dressing I staked a claim, which Feisal’s public consideration of me confirmed’. It was a big day for the leader of the Arab Army; he knew he had to be first to Damascus to claim victory for his Arabs and thus control of Syria, which he had promised them once he had installed Feisal as the king. Lawrence knew the future of the whole country would depend on who entered Damascus first.

He knew Allenby was at least a day or two behind him. He also believed Allenby’s ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement’ would hold: Allenby had by now agreed to allow Lawrence and his Arabs to enter first, because the Arabs could then assume control of Syria, which had been awarded to the French in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. (Allenby, who secretly resented his French Allies, preferred the Arabs, as they would limit French influence in this important oil-rich region). Lawrence also believed Allenby’s order that ‘no British or Australian troopers were allowed to enter Damascus unless absolutely forced to do so’.

It was a great moment for the Australian Light Horse when they conquered Damascus: it brought to a triumphant conclusion their campaign — which had started with the Battle of Romani in August 1916 — to rid Palestine of the Turks and dismantle the Ottoman Empire.

Setting off in his Rolls Royce, he had no idea that he was already well behind the Australian 10th Regiment (who argued later they had only entered Damascus because they were ‘absolutely forced to do so’ to find the Homs road to Aleppo). Then, to make matters worse, Lawrence was delayed for a while when a non-commissioned Indian officer guarding the approach to Damascus stopped him for questioning, thinking Lawrence and his party were Turkish, and trying to take them prisoner.

Eventually, the Rolls drove off again towards Damascus, led by Lawrence’s advance guard of the 5th Cavalry Division and some of his own Arab leaders on horseback, Nasir and Nuri.

8.30am

Lawrence and his party drove through the ancient main streets, which were still crowded with spectators who had greeted the 10th Regiment and who now assumed this party was a follow up from the Australians; and so they were not so welcoming nor excited. Gullett described this entry: ‘Lawrence rode into town with a few Arab horsemen on the heels of the advance guard of the 14th Cavalry Brigade. The Arabs believed that they shared with the Indians the honours of the first entry. Galloping with loud shouts down the streets, trailing their coloured silks and cottons and firing their rifles — they made a brave display. Their melodramatic demonstrations were in sharp contrast to the casual hard-fighting Australians who had risked all, nearly two hours earlier, thrilled the Christians but aroused the great Moslem crowds to a frenzy’.

Arriving at the city government building (the Serai), Lawrence leapt out of his Rolls, ran up the crowded stairs in his flowing robes, and entered the antechamber where his advance guards, horsemen Nasir and Nuri, were already meeting with ‘the new governor’, Emir Said, a pro-Turkish Algerian (anointed by the 10th Regiment just hours earlier). Emir Said announced he was now the governor, with his pro-Turkish Algerian brother Abdul Qadir (an old opponent of Lawrence) as his deputy! They were already governing Damascus with the support of Shakri el Ayubi, whom they pretended came from the house of Saladin. This carried weight, as the body of the last great conquering Muslim warrior, Saladin, who had captured Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1187, was buried in the Umayyad mosque in Damascus, which Muslims revered. Emir Said and his brother had authority, they claimed, because they had personally greeted the conquering 10th Regiment and surrendered the city.

Lawrence was furious; as leader of Feisal’s Arab Army, he had anointed Feisal as king and appointed Ali Riza al Rikabi as governor back in June 1917, when the Committee of the Seven had met and agreed on the post-war rule of Syria. Lawrence had even set up a committee for the transition of power to Feisal from the Turks. Shakria el Ayubi was only supposed to be the deputy to Lawrence’s pick, Ali Riza al Rikabi. But Ali Riza al Rikabi had earlier deserted his post in search of Chauvel, whom he believed had more power than Lawrence and could install him as governor with greater authority. While his back was turned, the Algerian brothers had taken over the transitional committee, got the numbers, and seized power. It was a mess. Lawrence later wrote he was ‘dumb with amazement’.

Meanwhile, when one of the disgruntled Arabs from one faction suddenly hit another from a rival faction on the cheek and threatened to kill him, they started punching and fighting each other until Lawrence and others pulled them apart. Lawrence may have ridden for two years with the Arabs, learnt their language, lived their lifestyle, and fought their cause, but he still could not understand them, let alone predict or control their behaviour.

And so the post-war political racial, religious, and tribal bickering had begun on day one.

9.30am

Chauvel left his base at Kaukab, a few kilometres south of the city, at 8.30am and drove into Damascus, arriving at 9.30am. He went in search of Lawrence, with whom he planned to establish the new government. The quick-thinking Lawrence, on meeting Chauvel, pretended that a ‘majority of the citizens’ had elected Shakri el Ayubi (who he wanted to govern now that his first choice Ali Riza al Rikabi had left town) as the head of a military government. Chauvel believed him and committed his Desert Mounted Corps to support Shakri’s new (but unofficial) government. Later, realising Lawrence’s power, Qadir, one of the Algerian brothers, fled, and so Lawrence imprisoned the other one, Emir Said, to avoid any future challenges.

Chauvel then returned to his base to prepare an official parade of the conquerors for the following day.

2 October, noon

Ordered by Allenby — and representing him — as the conquering leader, Chauvel rode through the town on horseback, leading a victory parade that was the biggest and most impressive ever to enter Damascus and one that showed who was in charge now.

This military column represented, Chauvel wrote, ‘every unit in the Corps including artillery and armoured cars, with the three divisional commanders and their staffs riding’ also in the parade. This show of strength would have impressed the locals as it featured the British Yeoman and gunners, New Zealand Light Horse, Indian Lancers, and French Cavalry, while a squadron of the 2nd Light Horse Regiment rode alongside Chauvel as his bodyguard.

Lawrence had asked Chauvel to let Feisal’s Arabs ride ahead of the British forces ‘to clear the way’, and Chauvel allowed ‘a small detachment of the Sharif’s gendarmerie to ride ahead waving large colourful Hejaz flags in the most unmilitary manner’. Although Chauvel thought this would placate Lawrence, he also believed this would show the locals which force had the most military might, as Chauvel’s included armoured cars, heavy artillery guns, and machine guns. Sergeant Frank Organ, who led a squadron from the 4th Light Horse, wrote that the parade was so long that the last members did not arrive till 3pm.

Bean reported the success of this parade and its impression on the locals, saying, ‘On the afternoon of the 2nd October Damascus a city of 300,000 — which till then was in ferment of looting and lawlessness, was quietened down by Chauvel with the age old method of an impressive parade of his battle-stained mounted troops riding through its streets and so the local people then re-opened their shops’.

These local people gawking at the parade included Arabs of every status, ethnic group, clan, religious faction, and background, but nearly all wearing long galabiehs of different colours. The majority of the onlookers were Syrians, of course, some in traditional flowing robes, some in European suits, jackets, and trousers. There was also a sprinkling of armed uniformed men representing the gendarmerie. Displaced Turks were there, too, in a wide range of dress including the classic fez, as well as Armenians, Greeks, and Jews in their distinctive dress. There were also Druze, with their colourfully painted cheeks and exotic hairstyles, from the Hauran region. It must have been an eye-opener for Chauvel and his Australian troopers, most of whom had never left home before. In fact, one of Australia’s youngest soldiers, Alec Campbell, 16, an AIF infantryman from Tasmania, had written home back in 1915, when in Egypt bound for Gallipoli, telling his mother that ‘all the fully grown men over here walk around the street in women’s dresses in broad daylight’.

By the end of that big military demonstration, the people of Damascus were convinced that the British and not the Arabs would be ruling. They may have seen Feisal’s Hejaz flags at the front, but the would-be king himself did not arrive until 3 October — three days after the 10th Regiment had entered the city and won the hearts and minds of the locals.

Lawrence was angry with Chauvel and his Australian forces, saying: ‘The sporting Australians just saw the campaign as a point to point with Damascus as the finishing post. We saw it as a serious military operation in which any unordered priority would be a meaningless or discernable distinction. We were all under Allenby and Damascus was the fruit of his genius’. Not surprisingly, he never admitted in his reports, articles, or books that the Australians beat him to this Damascus finishing post.

After the parade, Chauvel moved into town to set up his HQ. First of all, he cabled Allenby, confirming the capture of Damascus and generously including Lawrence and his Arab Army, saying: ‘The Australian Mounted Division entered the outskirts of Damascus from the north-west last night and at 6 A.M. today the town was occupied by the Desert Mounted Corps and the Arab Army’. Allenby then cabled the War Office confirming this: ‘We took Damascus at 06.00 today. Details follow’. The War Office later issued a communiqué announcing that ‘At 6 am on 1 October Damascus was occupied by a British force and a portion of the Arab army of King Hussein’; and that was how Lawrence and his Arabs, although they arrived later, were able to claim they were equal first into Damascus with the 10th Regiment.

But Chauvel, who knew his 10th Regiment was really first into Damascus, now got on with the administration of this conquered city, as the civil governor authorised by Allenby. Proudly, he wrote to his wife from the desk of the former Turkish governor of Damascus: ‘I am now writing this on Jemal Pasha’s desk in his own house in Damascus’.

He had lots of work to do before his troops departed for home. This practical work included such tasks as repairing the electricity for the city and cleaning up the collapsed hospitals.

The Australian Light Horsemen had dreamed of conquering Damascus since early 1916 — in fact, Ion Idriess was boasting about riding triumphantly into Damascus when his 5th Regiment was still in the Sinai! Sadly, by the time Chauvel’s grand entrance into Damascus actually took place, the greatest scribe of this whole story was back in Australia, recovering from malaria and wounds. Later, Idriess would embark on an exercise program, teaching himself to walk without a crutch, and working out in a gym to get his shrapnel-wounded body back to normal, which by 1920 he had succeeded in doing, against the odds.

It was probably just as well for Idriess, as this city of their dreams turned out to be a nightmare. These brave and skilled conquering heroes had entered a deadly city of disease, where, soon after the last shots were fired, many gallant Light Horsemen died (as did their vanquished enemy, the Turks, in their thousands). For now, despite surviving battle after battle in the desert over the last three years, Light Horseman after Light Horseman contracted insidious diseases spread by the sick and dying in and around the disgusting hospitals of Damascus, which were rife with malaria and influenza. As Sergeant James Williamson of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade (2nd Signal Troop) wrote to his girlfriend, Maude: ‘I was very pleased to leave Damascus miles behind me with all its filth and diseases — as it is such a filthy city. You could not imagine it Maude — it’s the worst place I have ever seen’.

Once the war ended, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force no longer had to care for the hundreds of thousands of Turkish POWs they had been capturing since the Palestine campaign began in the Sinai in August 1916.

Bean wrote: ‘A most dreadful legacy of war remained in the crowds of sick and dying and dead left behind by the retreating Turks in their appalling hospital, and in the onrush of malaria and pneumonic influenza that now mowed down the divisions of the Desert Mounted Corps. Their recent passage through areas swarming with infected mosquitoes and unequipped for prevention struck down a great part of the force. Yet these weakened Australians tried to help the even weaker Turks. Lieutenant Colonel T.J. Todd of the 10th Regiment’ (which had entered Damascus first) ‘was a sick man himself, but he took charge of 16,000 sick and dying Turkish prisoners organised in a camp at Kaukab and heroically fought for their lives against the apathy of the Arab authorities, before dying himself of the diseases he was treating them for’.

Even Idriess had contracted malaria earlier, well before Damascus. His account of the disease provides a vivid example of how infected Light Horsemen suffered. As he was also then wounded (which he saw as a blessing, as it got him out of the war), his story could apply to thousands, many of whom were not so lucky. As he wrote, ‘It’s a long time since I made an entry in the old diary. Here goes for the last entry.’

Even as the army was advancing north, ‘I felt wretched through some form of malarial fever — Jaffa fever they call it. The last phase of activity I remember was watching New Zealanders charge through the Turkish shells and take a ridge … I can remember the bayonets flashing, the hair-raising New Zealand war cries and the screaming “Allahs” of the Turks’. But ‘From then on I was too sick to notice or care what was happening’. Then Idriess felt worse, complaining, ‘if hell is any worse I don’t want to go there’. Although feverish, sweating, hallucinating a lot of the time, and also being unconscious every now and then, he reported: ‘The doctor with a lot of trouble managed to pull me through and one morning feeling much better, I went on sick parade to get my wretched septic sores dressed’.

But then, having never been seriously wounded since landing at Gallipoli in 1915, Idriess’s luck turned even further. ‘I was sitting down waiting my turn talking to the Red Cross sergeant on a gully-bank when — whee-ee-eezz crash! Instinctively we had thrown ourselves on our faces but the shell exploded too close. I spent awful seconds wondering if I was hit mortally. A whirlwind of bells was ringing within my head, and I knew that until the bells quietened I would not be able to think clearly at all. The first recognisable feeling was the numbness, with my mind trying to telephone to all parts of my body to find out which were still there and which were broken. Then quick as a flash I realized I had a good fighting chance although I still felt numb down my back. The bloody hole in my arm and also thigh did not matter. I should have been blown to pieces but there was not even a bone broken, just a dozen shell splinters’.

Idriess continued: ‘They put me in a sand-cart ambulance … after a painful bumpy journey hallucinating most of the way reached a dressing station … where they probed out some of the shell splinters … then a motor ambulance … then on a stretcher to the Australian Casualty Clearing Station I think in Jaffa … full of men suffering from malaria … where I lay in a restful fever guessing the war was over for me’. Idriess guessed right: after more treatment at Ramleh, where he was treated by ‘a captured Turkish doctor’, he was taken ‘by a captured Red Crescent train … through the desert to Kantara on the Canal and on through the streets of Cairo to a final clearing station with my leg now starting a haemorrhage … where the doctors confirmed the war was over for me’. He concluded: ‘I am to be returned to Australia as unfit for further service. Thank heavens!’

Others were not so lucky. William James Japhet (Billy) Smith, cousin of George Smith from South Australia, made it to Damascus, but that was as far as he got. He had already been stricken with chronic rheumatism, was ‘weak and wasted’, and had to retire from active service and become an ambulance driver. But now he contracted malaria, and sadly died eight days before the Armistice, with the Turks confirming the victory of the EEF, which he had fought so hard to achieve.

But one of those conquering troops who survived long enough to liberate Damascus, James Williamson, who hated the place, envied Idriess, as all he wanted by then was to get back to Australia to see his girlfriend again — hoping he could recognise her. On 7 October 1918, he wrote to Maude: ‘It is five years or more since I saw you last and a lot of changes can take place during that time … although I received your letter containing your photo yesterday at first glance I did not seem to think it looked like you at all but I think I could just still recognise you if we met’. Williamson, from New South Wales, had only met Maude once, as she lived in far-away South Australia.

Even though Damascus had turned out to be a hell-hole, on 2 October 1918, the newspapers broke the story as good news, with varying degrees of accuracy and political bias. The first Official Communiqué announced in different newspapers: ‘Damascus surrendered at 6 a.m. yesterday. On the morning of the 1st October the town of Damascus was entered by our mounted troops and also the Arab army. Over 7,000 Turks surrendered. Half the remaining Turkish Army had been destroyed at Damascus. After guards had been posted the troops were withdrawn from the town’.

Reuters then expanded on the story, claiming ‘the capture of Damascus represents a great Allied victory as it is one of the most important Turkish bases in Asia Minor and the principal supply centre for the captured Turkish armies. Its capture will create an enormous impression throughout Islam’.

Looking back on this historic moment, Australian correspondent Henry Gullett attributed the success of this great ride towards Damascus to efficient organisation. ‘Despite the extraordinary distances covered the Australian horses are still fit. One of the finest features of Allenby’s triumphant progress had been the remarkable efficiency of the Army Service Corps. On every advance the men and the horses have been well fed — there was no sign of the cavalry’s splendid drive weakening’. The mounted men were also given time off for resting, swimming, and fishing in places like the Sea of Galilee, he said. The success of the mounted cavalry capturing Damascus was not only due to their years of experience, he said, but because some carried swords like cavalry of old, which they often used as a more lethal weapon.

Recalling one of these sword fights, Eric McGregor of the 12th Regiment wrote: ‘When we marched on the town of Samat under the guidance of the 4th Cavalry Division who directed us to the point of assault and halted for final orders we came under terrific rifle and machine gun fire as the enemy had guns concealed in many buildings. But we attacked along with the 11th Regiment who charged mounted with drawn swords right up to striking distance’. After killing and wounding as many from horseback with their swords, the brave warriors of the 11th leapt off their horses alongside the 12th Regiment and ‘engaged in a desperate hand to hand encounter with their swords while the 12th used the bayonet in and outside the buildings before many enemy dead and wounded lay marking this bloody scene’.

Having demanded swords, McGregor said ‘the cavalry men of the 11th showed how well they could use these age old weapons’. The sword-wielding warriors ‘suffered rather heavily losing many killed and wounded — as the enemy were princely Germans who put up a determined fight but they suffered much more heavily than we did and lost a whole Garrison of prisoners to us. Their superior officers later considered it “a magnificent performance” especially as there had been no artillery support’.

After his Desert Mounted Corps’ epic 200-kilometre advance, Chauvel wrote triumphantly again to his wife: ‘We have had a great and glorious time, and the Chief who motored from Tiberias today to see us, has just told me that our performance is “the greatest cavalry feat the world has ever known”.’

Later military historians would agree with ‘the Chief’s’ assessment.

3 October

Not to be outdone (although he was two days late), Feisal arrived with his Arab Army on a special train from Deraa. He then quickly switched to horseback, and, with his bodyguard of 40 to 50 horsemen, got ready to ride into Damascus. After Lawrence got Chauvel’s permission, Feisal and his mounted men paraded through the already conquered city to stage a triumphal entry with all their Hejaz banners flying. Hopefully, there were still some spectators left who had not become bored with the series of triumphal conquerors riding into town.

Allenby also arrived that day by Rolls Royce, not for another parade, but for meetings with Chauvel and other leading lights, including Feisal, in the newly conquered city, aimed at sorting out who would be boss from then on in Damascus, Syria, and other parts of the Middle East.

Never had so many people had so many different experiences on the road to Damascus. These modern-day experiences certainly rivalled what happened to Saul aka Saint Paul all those years ago.

No matter who was first in Damascus, the fact was that the city was now captured and the Ottoman Empire was on its last legs. It had all been worthwhile, as it then appeared Allenby’s forces had helped bring the war to a close! The Daily News London reported a communiqué received from Zurich on 3 October ‘with the good news that Turkey has informed Germany of her determination to propose peace to the Allies’.

26 October

An Australian armoured-car detachment, which had travelled up the Homs road, finally captured Aleppo. They were supported by the Australian Mounted Division, who followed on from Damascus once they had recovered from sickness. Aleppo was an easy and final battle, as most remaining Turkish troops had all but withdrawn by then.

Bean wrote: ‘These were the last actions of the Light Horse in the war’.

30–31 October

Finally, on 30 October, after a successful negotiating session, Turkey officially signed an armistice at Mudros. It came into effect the next day, putting an end to the fighting in this long Palestine campaign.

11 November

The Armistice with Germany signed on 11 November 1918 put an end to the world’s worst war to date, which had started on 3 August 1914. Twenty million people had been killed and many more wounded and scarred for life.

Sadly, however, it did not stop the political fighting in all theatres of that war. Allenby’s forces had won the war in Palestine and dismantled the oppressive Ottoman Empire, but they never won the political victory that would enable long-term peace. In fact, throughout the Middle East, armistice or not, the different sides continued to fight for control. It was superpower against superpower and Arab against Arab, beginning soon after Allenby’s liberation of Damascus and Syria, which his forces had fought so long and hard to achieve. From that time onwards, the politics of the Middle East and especially Syria would become an unexpected and enduring nightmare that would stretch well into the future. More than 100 years later, as this book went to press, the war being fought for the control of Syria was the major conflict being fought on the planet.