CHAPTER 1

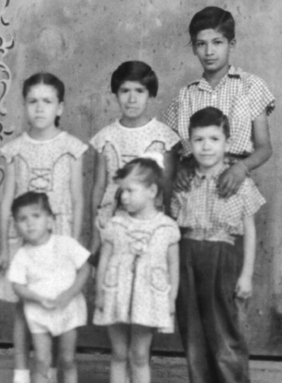

(Clockwise from top left) Irma, Laura, Tony, me, Lety, and Jorge in Autlán, 1952.

Maria, 1959.

I believe I grew up with angels. I believe in the invisible realm. Even when I’ve been by myself, I’ve never been alone. My life has been blessed that way. There was always someone near me, watching me or talking to me—doing something at the right time. I had teachers and guides, some who helped me get from one place to another. Some saved my life. When I look at the whole vortex of things that happened in my life, it’s amazing how many times angelic intervention came through various people. This book is because of them and is written to acknowledge them. It’s about angels who came into my life at the point where I needed them the most.

Bill Graham, Clive Davis, and my high school art teacher, Mr. Knudsen. Yvonne and Linda—two friends in junior high school who accepted me and helped me with my English. Stan and Ron—two friends who gave up their day jobs to help me get a band together. The bus driver in San Francisco who saw me carrying my guitar and made me sit near him to keep me safe when his route went through a very rough part of town. Musicians I played with who were my mentors—Armando, Gábor, and many, many more. My sisters and brothers, who helped me grow up. My three beautiful children, who are so wise and are now my teachers. My mom and my dad. My beautiful wife, Cindy.

I believe the world of the angels can come through anyone at any time, or at just the right time, if you allow yourself to move the dial on your spiritual radio just a little bit and hold it at the right frequency. For that to happen, I have to avoid making my own static, avoid ego rationalization.

People can change the way they see things by the way they think. I think we are at our best when we get out of our own way. People get stuck in their stories. My advice is to end your story and begin your life.

When I was just a kid, there were two Josefinas in our home. One was my mom, and the other was Josefina Cesena—we called her Chepa. She was a mestiza, mostly Indian. Chepa was our housekeeper, but she was more like one of the family. She cooked, sewed, and helped my mom raise all us kids. She was there before I was born. She changed my diapers. When my mom would try to spank me, I’d run behind Chepa and try to hide in her skirt.

When moms are pregnant, they spank harder and more often. When I was little, it seemed like my mom was always pregnant, and Chepa protected me from a lot of whippings. She was also the first angel to intervene on my behalf.

Things were already hard for my family. Dad and Mom had been married ten years, and he was traveling more and more to play his music and make money. Autlán did not have enough opportunities for a professional musician, so he started to travel for work and was gone for months at a time. You can tell his travel schedule by looking at his children’s birthdays. Starting in 1941, every two years another child was born. My three older siblings were all born in late October. The other four of us have our birthdays in June, July, and August.

When my turn came, Dad decided another child was one too many. The family was struggling financially. “Go over there and cook the tea,” my dad had said to Chepa when he found out my mom was pregnant again. He had gone out and come back with this bag of tea that was toxic and meant to induce an abortion. I’m not sure how many times that happened before I came along, but I know that in total my mom was pregnant eleven times and lost four of her babies. After Antonio—Tony—then Laura and Irma, I was the fourth to come along.

“Boil this thing, and I want to see her drink all of it,” my father told Chepa. But she knew my mother did not want to lose the child. When he wasn’t looking Chepa pulled a three-card monte—substituted one tea for another. She saved my life before I was even born.

It was my mom who told me this story—twice, in fact. The second time, she forgot she had told me and was totally surprised when I told her I knew. It could not have been an easy thing for her to do. Can you imagine telling your child that he was almost aborted? Or that he was almost called Geronimo?

I was born on July 20, 1947. My dad wanted to name me Geronimo. I would have loved it, personally. It was because of his Indian heritage—he was proud of that. I think it was the first and only time my mom put her foot down about our names and said, “No, he’s not Geronimo. He’s Carlos.” She picked the name because of Carlos Barragán Orozco, who had just died. He was a distant cousin who had been shot in Autlán. I had light skin and full lips, so as a child Chepa used to say, “Que trompa tan bonita”—what beautiful lips. Or they would just call me Trompudo.

I’ve seen my birth name listed in some places as Carlos Augusto Alvez Santana—who the hell came up with that? My given name was Carlos Umberto Santana until I dropped the middle name Umberto. I mean, Hubert? Please. My full name now is simply Carlos Santana.

Many years later my mom told me that she had a premonition of what kind of person I would be. “I knew you were going to be different from your sisters and brothers. All babies grab and hold on to the blanket when the mother covers them. They pull on it until they have a tiny ball of lint in their little hands. All my other babies would rather bleed than open up their fists and give it to me. They’d scratch themselves first. But every time I would open your hand, you let it go so easily. So I knew that you had a very generous spirit.”

There was another premonition. My mom’s aunt, Nina Matilda, had a head of hair that was totally white, white as white can be. She would go from town to town selling jewelry like some people sell Avon products. She was good at it, too—a very unassuming old lady who would show up on people’s doorsteps and open up a bunch of handkerchiefs containing all this jewelry. Anyway, Nina Matilda said to my mom after I was born, “This one is destined to go far. El es cristalino—he is the crystal one. He has a star in him, and thousands of people are going to follow him.” My mom thought I was going be a priest or maybe a cardinal or something. Little did she know.

People ask me about Autlán: what was it like? Was it city or country? I tell them, “You know that scene in the movie The Treasure of the Sierra Madre when Humphrey Bogart is in a shootout in the hills with banditos who claim to be Federales? And one of the banditos says, ‘Badges? We don’t need no stinkin’ badges!’”

That’s Autlán—a small town in a green valley surrounded by big, rugged hills. It’s actually very pretty. When I lived there in the early ’50s, the population was around thirty-five thousand. Now it’s around sixty thousand. Only recently did they get paved roads and traffic lights. But it was more together than Cihuatlán, and that’s what my mom wanted.

My memories of Autlán are those of a child. I was only there for my first eight years. At first we lived in a nice place in the middle of the busy town. To me, Autlán was the sound of people passing by with donkeys, carts—street sounds like that. It was the smell of tacos, enchiladas, pozole, and carne asada. There were chicharrónes and pitayas—cactus fruit—and jicamas, which are like turnips, big and juicy. Biznagas—sweets made from cactus and other plants—and alfajor, a kind of gingerbread that’s made with coconut. Yum.

I remember the taste of the peanuts that my dad would bring home, still warm from being roasted—a whole big bag of them. My brothers and sisters and I would grab them and crack them open, and he’d say, “Okay, who wants to hear the story of the tiger?”

“We do!” We’d get together in the living room, and he’d tell us a great story about El Tigre that he would make up on the spot. “Now he’s hiding in the bushes, and he’s growling because he’s really hungry.” We would start huddling close together. “His eyes are getting brighter until you can hear him go… roar!!”

It was better than television. My dad was a great storyteller—he had a voice that triggered our imaginations and got us involved with what he was saying. I was lucky: from as early as I can remember I learned the value of telling a good story, of making it come alive for others. It permeated me and I think later helped me in thinking about performing music and playing guitar. I think the best musicians know how to tell a story and make sure that their music is not just a bunch of notes.

We lived in a few different houses in Autlán, depending on how Dad was doing bringing in the money. There was one that was on a little run-down parcel of land in between other houses—my dad probably got a deal on that because he had friends. The best one was more like a house with a number of rooms and a big yard with a working well. There was no electricity or plumbing—just candles and an outhouse. I remember this house was closer to the ice warehouse than the others. The ice was stored in sawdust to keep it from melting, and we could go get it anytime and bring it home.

From Autlán to Tijuana and even San Francisco, it seemed like we never had much space. We usually had just two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a living room. Mom and Dad always got their room, and the girls got theirs, so we boys would sleep on the couches or in our own room if things were going well with Dad and the money.

I guess my dad must have been doing pretty good when we started in Autlán. Tony and I, and later Jorge, shared a room. But there were compromises. The roof was a little rotten, and I remember getting ready to fall asleep one night when suddenly there was a thud. My brother Tony said, “Don’t move—a scorpion just fell, and it’s next to you.” Next thing I heard was the creature skittering across the floor, running away. Man, that was a creepy feeling.

A sound that is really beautiful is the plop of mangos falling down when they’re ripe. They’re big, red, and they smell really beautiful. I would play in the yard, which had mango and mesquite trees, and there were these chachalacas—little birds that are a cross between a pigeon and a peacock. They’d wake us up in the morning because they can be so loud.

That yard had a dried-up well, and for some reason when nobody was looking I decided to throw some little baby chicks down there. Tony saw me and said, “Hey, what are you doing?” and I started climbing down to go get them, and he grabbed me before I hurt myself. “Hey! Don’t go in there, stupid. It’s really deep.” We covered up the hole later on to make sure nothing bad happened.

I don’t think I was a troublemaker—I was just a normal, curious kid. I knew right from wrong. The yard had this old wall that I didn’t know was starting to fall apart. It had all these vines on it, and one day I started pulling on them to get at the seed pods. I’d open them so the seeds, which each had little parachutes, could go whoosh and fly away. I was really enthralled with them, so I kept pulling on the vines until suddenly part of the wall collapsed and landed right on my feet, tearing up my huaraches and smashing my toes.

My feet were bleeding, and I was scared to death that my mom was going to beat me because the huaraches were brand new and I had destroyed the wall. Everybody was looking for me for a long time. Chepa finally found me hiding under my bed. “Mijo, what are you doing there?” She saw my feet and gasped. She told my mom, who felt really bad that I was so afraid of her that my first reaction was to run and hide. She didn’t spank me—that time.

Life at home was about living by Mom’s rules. She was the disciplinarian, the enforcer. It was her house, and she was in charge. Dad was gone most of the time, so it was just us kids and our mother, and she could be real intense. My mom and dad were not really good at showing affection and demonstrating their love—to us or to each other. Of course we honored our mom, but she was not the huggy-bunny kind.

Looking back, I realize that she was learning to be a mom while doing all the mom stuff and Dad was learning to be a father—and a husband. My parents did the best with what they had and who they were. They didn’t have any formal education. I don’t even know how they learned to read or write. They taught us, by example, that you make your own way. “Maybe we don’t have much in the way of education or money, but we’re not going to be ignorant or dirty or lazy.”

Mom had a modest beauty about her. She was tall, and her style was elegant but not lavish. She didn’t like extravagant stuff—but she never wore anything that made her look cheap or desperate. We kids saw how she carried herself—she walked differently from the way most other women walked. Even when we were very poor, you could tell she came from a certain kind of upbringing, some kind of privilege.

My mom had a system with us kids. We all had roles, starting from an early age. “Today you two will clean the beds and the floor, and you two will do the dishes and get the pots and pans clean. Tomorrow you guys’ll switch. And when you sweep I want you to straighten up and make your back look like that broom—straight. Put your spine behind it, and don’t just move that dirt around; get rid of it. When you wipe the dinner table don’t just smear it, clean it up. Get a hot, hot towel so the steam can wipe out the germs. I don’t want any mugre, any filth. We’re poor, but we’re not filthy poor. No one is going to embarrass the family or embarrass the name Santana.”

It was amazing. She could tell if we were putting our backbones into it, and if we didn’t—pow! We would get it. Now we appreciate what she did, because she created a certain thing that all my sisters and brothers and I have—a pride in what we do and in our family. But back then it was tough. My mom was really intense to live with. We were both the same kind of intense. She questioned everything, and so did I.

I remember one time she was angry at me for some reason, and I just took off. I must have been all of five or six years old. I left the house, pulling this little toy crocodile on wheels behind me. I wasn’t crying or sad, I was just exploring and getting away from Mom, thinking about avoiding the rocks with my crocodile and not hitting certain lines in the pavement. I got involved with people in the market and the horses passing by. I was also thinking, “This is really cool—I can put a distance between my angry mom and myself for a little bit.”

When my sisters found me, they ran up to me. “Weren’t you afraid, being by yourself? Didn’t you get lonely or scared?” Truth is, I didn’t have time to think about it. I think I was born living in the now, not being concerned with what’s up ahead. I think that experience planted a seed in me so that in years to come I wouldn’t limit myself or be so self-absorbed with fear. I would feel welcome walking into new and strange places, like, “Oh, I’m in Japan!”—and my eyes would get bigger as I would start noticing the beautiful temples. Or, “Oh, I’m in Rome; look at this street; look at that one!” and I’d be off exploring.

When you’re a child everything seems new and wonderful—even the scary stuff. I first saw a fire when the local supermarket burned. Apparently even back then somebody wanted to collect insurance, so he burned down his own store. I had never seen flames so big. The sky looked red and everything.

Another time I saw a man almost die when he was badly gored by a bull. I must have been five or six. I remember a bunch of men walking through town with posters announcing a bullfight. That weekend my mom dressed me up, and we went to the Plaza del Toros, which was on the other side of town from our house. I walked in the parade at the start of the event—marching to the pasodoble next to this little girl who was also dressed up. Years later I was able to tell Miles Davis that he and Gil Evans got it right when he did “Saeta” on Sketches of Spain. That’s the tempo and feel at the start, when everyone walks around the ring.

You only have to see a few bullfights to know that when most bulls enter the ring they run to the center and look around, snorting and angry. But that day a bull came in and just looked at the toreadors. He was cool, like a fighter sizing up his opponent—like Mike Tyson before he had money. Then he ran. But he jumped over the fence, and people were leaping out of their seats and running for their lives!

They somehow got the bull, opened the gate, and led him back into the ring. He went running into the middle again and stopped and just stood there, still saying, “Okay—who’s got the guts to come and deal with me?” One bullfighter stepped up with his red cape, but this was no idiot bull—he wasn’t going for the color. He was going for the guy. The bullfighter got too close, and one of the bull’s horns got him right in the side. They had to distract the bull so they could rescue the man. The guy lived. I don’t know what happened to the poor bull.

I remember when I started going to Autlán’s public primary school, the Escuela Central. There were paintings of all the Mexican heroes on the walls—Padre Miguel Hidalgo, Benito Juárez, Emiliano Zapata—and we began to learn about them. I liked the stories about Juarez best because he was the only Mexican president who had worked in the fields as a peasant and was a “real Mexican”—that is, part Indian, like my dad. My favorite teachers were the best storytellers: they would read from a book and make it all come alive—the Romans and Julius Caesar, Hernán Cortés and Montezuma, the conquistadors and the whole conquest of Mexico.

Mexican history is a hard subject to talk about now, because as I grew up I quickly learned that it’s pretty much been a merry-go-round of everybody taking turns raping the country: the pope, the Spanish, then the French and the Americans. The Spanish couldn’t beat the Aztec warriors with their muskets, so they spread germs to kill them off. I could never swallow that one. The history I was taught was definitely from a Mexican perspective, so I was curious about this country up north that was founded by Europeans who took it away from American Indians and then from us Mexicans. To us, Davy Crockett got killed for being in a place he shouldn’t have been to begin with. The next thing you know, Mexico lost all its territory, from west Texas all the way up to Oregon. All that originally belonged to Mexico. From our perspective, we never crossed the border. The border crossed us.

Our awareness of America was through its culture. My mom wanted to get away from her hometown because she saw a world of elegance and sophistication in the movies of Fred Astaire and Cary Grant. I learned about America from Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, and Gene Autry. And Howdy Doody. I would learn a lot more later through the music, but first it was through the movies. In Autlán there wasn’t a proper theater, so the people used to wait until nighttime and hang a big sheet across the middle of a street and project the movies on it, like a drive-in without the cars.

I’ve always been conflicted about America. I would come to love America and especially American music, but I don’t like the way America justifies taking what didn’t belong to it. On the one hand, I have a lot of gratitude. On the other hand, it can piss me off when it puffs up its chest and has to say, “We’re number one in the world, and you’re not!” I’ve traveled the world and seen many other places. In many ways, America’s not even in the top five.

I was not a great student. I didn’t enjoy the classes. I got bored very quickly and had trouble sitting still. As a child I never wanted to sit and learn things that didn’t mean anything to me. At recess time, I was allowed to go home for lunch. It was a long walk, and I liked doing that, though one time I remember going back home to find that my mom had prepared some chicken soup, even though it was hot outside. I said, “I don’t want to eat soup.” Of course, like any mom, she said, “Eat it; you’re going to need it.”

When she turned her back, I grabbed a whole wad of red chili powder that was on the table and dumped it in the soup. “Mom, I made a mistake. I wanted a little bit of chili, but the whole thing went in there!” She saw right through that. “Eat all of it.”

“But Mom…” So I ate it. Man, I got back to school fast after that!

I was young and could be foolish, but I was always learning, especially out in the world. In Autlán, I was old enough to understand that my father was a musician, that he made a living playing the violin and singing. My dad played music that was about functions. It was music to celebrate by—we need some happy music, music to raise our glasses to. Can’t have a party without some polkas to dance to. Music to help someone serenade his girl, to get her back after he messed up. Music to feel sorry for yourself—cry-in-your-beer music. I could never stand that last kind of music—there’s way too much of that in Mexico. I love real emotion and feeling—I guess you call it pathos—in music. I mean, I love the blues! But I don’t like it when the music is about whining or feeling sorry for yourself.

I got to know the kind of music Dad liked—Mexican popular music of the 1930s and ’40s was his bag. Love songs that everyone would hear in the movies, and the ballads of Pedro Vargas, a Cuban singer who was really big in Mexico—“Solamente una Vez,” “Piel Canela.” He’d play those melodies with such conviction, slow them down, either by himself at home or with a band in front of an audience. It didn’t matter. But he knew a wide repertoire of Mexican music—he had to. Mexican music is basically European music: German polkas—oompah, oompah—and French waltzes.

By the late 1940s, around the time I was born, corridos—history songs and all that macho cowboy stuff, including mariachi music—started to push away all the other music. My dad had no problem with that. He would play the mariachi standards that everyone knew. He would get dressed up in those costumes and the wide-brimmed hats. That’s what people wanted to hear; that’s the music that got you paid to play. It’s like so many fathers and sons—he had his music, and I had to have mine.

But that came later. In Autlán I was too young to really appreciate what my dad’s being a musician meant for us. Later on I found out that he was supporting not only our family but also his mother and a few of my aunts—his sisters—with his music. His father, Antonino, was also a musician, as was Antonino’s father before him. They called them músicos municipal—municipal musicians—and they played in parades, at civil functions, and were paid by the local government. Antonino played brass instruments. But he developed a drinking problem and could no longer function. Then he dropped out of the picture. I never met him—the only thing I ever saw of my dad’s father is in a painting. There he looked like a real, real Mexican Indian: he had a large nose, his hair is all messed up, and he was standing with a band and playing a córneo, a small French horn. That’s the look of Mexico for me, the real Mexico.

My father never talked about those things—not then, not really ever. He was one of ten children, and they grew up in El Grullo, a small town halfway between Autlán and Cuautla, where he was born. We only visited a few times, when my mom wanted to appease my dad. I remember my grandma frightened me—her silhouetted shadow on the wall, cast by the candlelight, scared the hell out of me. She was sweet as pie with my dad, but with us and my mom she was a little guarded.

That’s where we met our cousins—my aunt’s kids. My siblings and I may have been from a small town, but we were city kids compared to them. They were country, country, country—which meant that we got a real education. They would say, “Come here; see that chicken? Look in her eyes.”

“Why? What’s wrong with her eyes?”

“She’s going to lay an egg!”

“What?”

I didn’t even know chickens laid eggs. Sure enough, the chicken’s eyes got wide, it started clucking, and all of a sudden—pop! Out came this steaming egg. I was like, “Wow!” Not until we visited my grandparents did I experience that or the sound and smell of cow’s milk when it hits the bucket. There’s nothing like it.

It came to a point one afternoon when nature was taking its course and I had to go to the bathroom. I was used to toilets or an outhouse, but I didn’t see any around. So I asked my cousins. “See those bushes?” they said. “Do it right there.”

“No—outside? Really?”

“Yeah, right there beside those bushes. Where else?”

“And how do you clean yourself?”

“Leaves, of course.”

I was like, “Uh… okay.”

So I was over there doing my business. The next thing I knew I felt this wet, hairy thing touching my booty. I turned around and got the fright of my life—it was a pig’s snout, and he was snorting and trying to eat my stuff! I was like, “Aaaah!!” I ran out of there with my pants still around my knees, trying to get away from that hungry pig, and all my cousins and brothers and sisters were laughing so hard they were falling over. They didn’t warn me to be careful of the pigs and do your business fast, because that’s what pigs love to eat. It was enough to make me stop eating bacon.

When I was seven years old, our family was as big as it was going to get, and things began to get really tough. We were seven kids—from thirteen-year-old Tony down to baby Maria, plus Chepa and a small dog that looked like a white mop and had no name. Some guy had asked my mom to hold it for him and never returned to get it back. My dad was working harder than ever, trying to keep money coming in for food, and he started to leave for longer periods. I missed him all the time; everyone did. When he would come back home, we all wanted to be with him, especially my mother. But they would fight—about money and about women.

Through the eyes of a child, I saw only the fighting. They would yell at each other, and I hated that, because I loved my dad and my mom. I didn’t understand the reasons behind the behavior, and I didn’t know words like discipline and self-control. Hearing them fight when I was a child was like looking at a book with words and pictures, and you get a general idea from the pictures but you can’t read what’s written to get the full meaning.

All I knew is that they would go at it, and then my dad would leave and come back at four in the morning with a bunch of musicians, and he’d serenade my mom from the street outside. You could hear them coming, and all of us would wake up. My dad would stand right in front of our window and play the violin and start singing “Vereda Tropical.” It was their make-up anthem. Like B. B. King, my dad never sang and played at the same time, ever. He’d sing the lines—“Why did she leave? You let her go, tropical path / Make her return to me”—and then to bring it home he’d embellish the melody with the violin.

We’d watch my mom, and if she went to the window and opened the curtains, we said to ourselves, “They’re going to be all right, thank God.” It was beautiful, and we kids felt relieved. “Okay, they’re going to keep it together.” That happened a number of times.

Some of their loyalty to each other I think came from experience, from learning to get past the rough stuff. When they were first married my mother couldn’t cook at all. She’d been raised on a ranch with servants and cooks. When she first tried to bring him food, my dad was rough. “I work really hard. Don’t waste any more money, and don’t ever bring me this crap again. Go next door and ask the neighbor to teach you how to cook. Go ask somebody.”

My mom did that. “I swallowed my pride,” she told me. The neighbors said, “Don’t worry, Josefina, we’ll teach you. You put grease in here and then a little piece of tortilla, and when it turns a certain color, then you can put the chicken in.” My mom eventually became one of the greatest cooks ever.

Still, in the first years of their marriage, sometimes my mom would take her babies and go back to Cihuatlán. This happened a few times, until my grandfather said, “Look, this is the last time. If I’m going to take you in, you need to stay here. But if you’re going to go back with him I don’t want to hear about him mistreating you. You need to make a choice.”

My mom made her choice—she stayed in Autlán.

After a few years my dad was in better graces with my grandfather, who invited the whole family to come to his ranch. At one point, my mom told me, her father asked my dad to join him and his workers in a big room, and they all gathered around.

My grandfather was going to play a joke on my dad. “José, would you like a coconut?”

“Sí; gracias, Don Refugio.” Don Refugio was what they called my grandfather.

He gave my dad a big machete and a coconut. “Okay, go ahead,” he said. My dad didn’t know how to hold the knife, so he started hacking at the thing, making a mess, and everybody started laughing. My mom immediately saw what her father was doing. She stepped up and said, “Don’t do that, José. You’re going to cut your fingers. You’re a musician.” Then she opened my father’s instrument case, grabbed the violin, and handed it to my grandfather. “Okay, now you play a song,” which of course he couldn’t do.

Everybody was stunned, you know? In that culture at that time, you never questioned your parents. But she didn’t like what her father was doing and wanted to make a point. My mom was really different.

It was years before we kids could piece together the story of her family. My mom would open up now and again and give us a little information, such as the fact that she was one of eight kids and that she grew up with her grandparents. It was common in Mexico: some children were sent to live with their grandparents for a while, then they’d come back home. She never told us why she was the one in her family who was sent away, but from an early age my mother was strong-willed and would speak her mind. I think her grandmother enjoyed hearing her opinions and allowed her to say things and spoiled her a little, so that when she came back home and tried to do that she’d get into trouble. Plus she wasn’t the center of attention anymore.

My mom did mention that her father was well-off, and that after her mother died—this was in the early ’50s, when I was still very small, so I don’t remember my grandmother at all—my grandfather didn’t know how to keep things together. He started lending money to people who couldn’t pay him back, which was something his wife would never have allowed. She had been in charge of the family’s finances. That’s what I heard from my mom. What I heard from other people is that my grandmother died from some intestinal problem that developed because she found out that her husband had a child with one of their maids. From then on, everything went downhill, and my mom was at war with her dad and his new lady.

Later I learned from my mom that my dad was not an easy person to live with, either. He was very old-school in his way of being a husband. My mom told me what he said to her when they decided to get married: “You’re never going to get a ring, or a postcard, or flowers, or something special on birthdays or Christmas.” He pointed to himself and said, “I’m your present. As long as I come home to you, that’s what you get.” I was like, “Damn, Mom! That’s a little intense. Would you still do it all over again?”

“In a breath. I always wanted a real man. He’s a real man.”

My mom never rolled with any man other than my dad. She only danced with him maybe seven times, if that. But she never danced with another man, either. And he never got her a ring. I don’t understand that, and I’m sure a lot of women today would scratch their heads. But most women I know didn’t grow up in that generation or in that culture or experience what she did.

My sister Laura told me years later, when she had a beauty shop in San Francisco, that my mother was there having her hair and nails done, and the women were talking. This one lady is going on about her rings: “See? I got this from my first husband, and I got this from my second husband.” Someone said, “Hey, Josefina, we notice you don’t have a ring.” She looked at them and said, “I may not have a ring, but I still got my man.”

In Autlán, it seemed my dad could not help but play around—he just loved women, and women loved my dad. He was a charismatic man, and he had a way with women. He knew his music had an effect on them—any good musician knows that and can see it. I notice it. If you play from your heart, as my dad would, it can sweep women off their feet. You don’t even have to be good-looking, man: just play from the right part of your heart, and women are transported to a place where they feel like they’re beautiful, too. He was part of a very macho generation. You showed how much of a man you were by how many women you had.

Of course that didn’t square with my mom. She did not buy into that excuse, and it caused problems between them. She took the fight outside the house, and she didn’t care who knew it.

One evening around six or seven my mom yelled, “Carlos, come here!” She started cleaning me up, combing my hair. “Where are we going?” I asked.

“We’re going to church.”

“But it’s not Sunday.”

“Don’t talk back.”

Okay, we’re going to church.

So she’s ready, I’m ready, and we headed out of the house like it was on fire. My feet were barely touching the ground she was walking so fast. We passed the church and kept going. “Mom, the church is over there.”

“I know.”

Okay.

Two or three blocks later we suddenly stopped outside of a store. We waited outside until the last customer left and the lady behind the counter was by herself. My mom went in and said, “My name is Josefina Santana, and I know you’re messing with my husband.” Then she grabbed the long, beautiful braids this woman had, pulled her right over the counter, got her on the floor, put her knee on her neck, and started beating the crap out of her.

You know, when you go to a boxing match it sounds so different from hearing people getting beat up on TV. It’s so different when it’s happening right in front of you—you never forget it. Then when it was over Mom walked out, grabbed my hand, and we walked back just as quickly. My mom was strong. Of course my dad heard about what happened and came home and they fought. I mean really fought—he shut the door to their room, and it was terrible. We kids were all scared. We could hear everything and couldn’t do anything about it.

Years later my mom told me stories that were kind of brutal. She didn’t need to tell me—I remembered hearing those sounds and not being able to do anything about them. I’d say, “I don’t know why you stayed with him so long.” From what I learned later, there were mainly two things that set things off for my dad—my mom getting jealous and her getting between him and his family. My dad loved his mom and his sisters and provided for them when he could. But my mom felt he had his own family to take care of, and sometimes when a letter would come to my dad from them my mom would open it and start arguing with him. He’d get angry because she was opening his mail and getting into his stuff, and bam! That door would slam shut again and we’d hear the fighting.

One time after we moved to Tijuana, Tony came home for something that he forgot and witnessed the whole thing going on. But by that time he was old enough to do something. He kicked in the door and picked up my dad from the floor so that his legs were dangling in the air. They were looking at each other eye to eye. Our dad was tight in his arms, and Tony said, “Don’t you ever touch my mom like that again.” Then he put my dad down slowly and walked out. It got really quiet in there. That was my brother Tony.

The last time any of that happened was in San Francisco. Dad came near Mom, and she grabbed a big black frying pan. “No, José. We’re in America now,” she said. “You try it and you’re going to get hurt.”

I think the cycle of violence has to stop, and it’s up to each of us to do all we can to stop it. So much violence comes from fear and ignorance, and from that word I truly hate: macho. Because macho is fear—fear of being too “feminine” and not being man enough, fear of being seen as weak. It can be like the worst virus, an infection that starts in the family and goes out into the street and spreads through the world. Violence has to be stopped where it starts—at home.

To be honest, I once hit a woman.

When I left home for the first time I moved in with a woman who had two children, and we got into it one night. She got a little crazy, then I did too, and I tried to avoid the argument but the next thing you know we’re throwing punches at each other.

To this day I ask myself why I didn’t just walk away. It wasn’t complicated. I had four sisters and my mom at the time. Now I have an ex-wife, a new wife, and two daughters—I would not want anyone to treat any of them like that. In fact, I don’t want anyone to treat anyone like that, male or female. As men, we are given power, but with that power comes responsibility. I think that’s something that should be part of the curriculum in schools—how to treat yourself and others.

For me it happened that one time, never again. That was enough for me to see what was happening, how I was going down a path of false, macho bullshit. Knowing it happened in front of my girlfriend’s two children made me sick to my stomach. It made me think back to when I was a child in Autlán and the way I felt when I would hear my dad hitting my mom.

I still wonder how much of my dad spilled into me. In so many ways I can thank my dad for being an example of what I should and should not do.

My mom never stopped getting upset when she thought about women messing around with my dad. I remember another time when she was boiling water to throw on this lady. Chepa wrestled it away from her and made sure she didn’t end up in jail. With my mom, when jealousy took over, she didn’t have the benefit of thinking about her children. She just wanted to beat the crap out of any woman who came between her and her man. I’m sure when we left Autlán, the whole town breathed a sigh of relief—definitely the women.

The end result was that my dad stayed away from Autlán more. He was making less and less money in the towns around Jalisco, and he didn’t like Mexico City, so he started to travel farther away, as far north as Tijuana, on the border of the United States. It was the mid-1950s, and Tijuana was a big party town with lots of work for musicians. He’d be gone, and then we’d get a letter with some money and sometimes a photo. One he sent showed him standing next to Roy Rogers and Gilbert Rolland—a Mexican actor who was making it big in Hollywood back then. I used to carry that picture of him in my back pocket all the time. I’d be riding around on a bike, take it out and look at it, and show it to everybody. “Just look at it,” I’d say. “Don’t touch it; you’re going to rip it, man.”

Dad’s career was not stable. Sometimes he got together a group, and they would travel caravan-style to a hotel gig for a few weeks—a large group of eight or nine. Many times he was on his own. He’d take a bus into a new place, find the musicians, arrange a trio or quartet, and play in the town square. They would go to various restaurants and ask if they could play inside or outside or go from table to table. Or they might find the best hotel in town and ask if it was okay to come in. “No, sorry—we already have a band playing tonight.” Or, “Yeah, okay, no one else is here; come on in.”

That’s how they did it back then. No posters or advance promotion, no ticket sales, no box office. All the business was done on the spot—asking the tourists for fifty cents or a dollar per song, asking the restaurant to feed the band if everyone was happy. Then it was back to a couch at one of the musician’s homes or back on the bus. “This place seems to be a little slow. Should we try Tecate? Maybe Nogales?” Then it was back on the bus again.

That’s how my dad made his money—he asked to play. I really admire the fact that he was able to build a career that way, to bring in the money and feed us. It wasn’t easy.

After a while it seemed like he was always gone. When we were in Autlán, it got to the point that my dad would be gone for months and months at a time. Years later, when I’d hit the road with Santana and people would say something about the time I was gone away from my family, I’d say, “Nah, it’s not so crazy.” I would go on the road for four or five weeks at a time when my kids were growing up, but that would be the most that I would do. I learned from what I experienced in Mexico. I think I was pretty balanced compared to what my dad did.

At one point a year had gone by, and suddenly my dad had come back, and I was so happy and proud. He’d take me with him when he went riding through town on his bicycle, and he let me ride on the back, grabbing hold of his belt—he’d wear this thin golden belt, very fashionable at the time. I loved the way he smelled. He’d use this Spanish soap called Maja. I can still remember that scent to this day.

I was so proud—he’d be waving at people, and they would greet him like he was a returning hero. “Oh, Don José!”

“Hey, how you doing?”

Every few minutes someone would stop us. “Do you remember me? You played my quinceañera!” Or someone would say, “You played my baptism!”

“Oh, yes, of course. Please give my best to the family.”

“Oh, Don José, thank you. Can we take a picture?”

I learned early on that I had to share my dad—with my family, his work, and his fans. All us kids knew this. My sister Maria told me that after someone would stop to say hello, she would ask my father, “Do you know that person?” His answer was, “No, but saying that makes them feel good.” I always remembered that about my dad. It was part of the eulogy I read at his funeral in 1997.

When I was eight, we hadn’t seen my dad in almost a year, and we had gone from living in the middle of Autlán to living in the worst neighborhood in the area, just a few blocks from the edge of town. It was a small two-room place filled with cooties—that’s lice. It also had chinches—bedbugs—and pulgas, or fleas. When a letter containing a big check came from my dad, my mom had had it. It was time to leave Autlán.

It was almost like Dad was trying to get rid of us: “Here’s some money for rent and maybe buy a stove or something.” My mom took the letter to the middle of town, where all the cab drivers hung around. She knew a guy named Barranquilla, who was close to my dad. She told him that she had received a letter from José telling her to give Barranquilla some money to drive the family up to Tijuana. “He told me to pay you half and that he’ll pay you the rest and more when you get us there. Take this money and pick us up on Sunday, okay?”

Of course, Barranquilla thought this was weird, since my dad never said anything to him. He asked to read the letter. My mom acted as if he were out of his mind. “No! You can’t read this—you crazy? There’s personal stuff in here!”

So this is Thursday or Friday. My mom started selling off everything she could—furniture, whatever we had. She got together a little bit of food and money for the trip, enough to pay for the gasoline. On Sunday, she got us all up and made sure we were washed, dressed, and looking good. Barranquilla brought the car around, and it was like a big tank—one of those big American sedans you smelled before you saw. My sisters, brothers, and I—our eyes were really big, wondering. “Where are we going, Mom?”

“We’re going to your dad,” she said. I think only Tony and Laura knew before that morning that we were leaving.

My mother put my four sisters, my brothers, Chepa, the dog, and me in the car, got in, and said, “Nos vamos.” It was five thirty in the morning. We were heading for a man we hadn’t seen in a year. We had enough money for a one-way trip and no guarantee we would find him. I remember looking out the back window and watching the town get smaller. We headed east out of town. West would have taken us to the coast, and the east road went for a while and then forked. One way went to Guadalajara, and the other way went left, toward El Norte. That was the road that led to all sorts of possibilities, the promise of a good life—El Norte. Tijuana? Who cared that it was on the Mexican side of the border? To my mom, Tijuana was America. We were going to join Dad, and we were going to America. That was the road we took.