CHAPTER 2

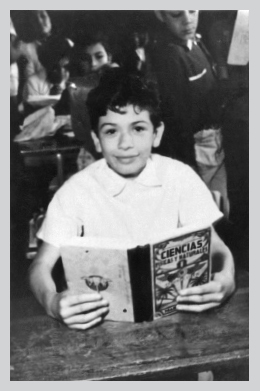

Me in grade school, 1954.

In Tijuana, very early in the morning, when the sun was just coming up, I would walk to school. Just outside of town I would see a line of people—Indios, mestizos—walking like they were in some religious procession, going up into the hills, where they could get red clay. They’d take chunks of clay home, where they’d mix it with water and shape it into two-feet-high figurines, about as tall as from your elbow to the end of your fingers. They’d let them dry, then paint them white and add other details, and there! You’d have the Virgin of Guadalupe—the patron saint of all Mexicans. She would look really beautiful by the time they were done.

They’d take the statues into town to sell to tourists or anyone near the cathedral in downtown Tijuana—Our Lady of Guadalupe. Or they’d walk between the cars in the middle of the road, the way they sell oranges and stuff like that. People would buy the statues, take them home, put flowers or candles on them, and start praying from the heart to these little figures. Who’s to say whether their prayers were answered? Just days before, they had been nothing more than some red clay up in those hills.

When I arrived in Tijuana, I was a Mexican kid like so many others. I was just raw material, man. I didn’t have much hope to go anywhere or get any higher than I was. Everything that I became began to crystallize in that border town—becoming a musician and becoming a man. Miles Davis used to compliment me in a way he understood. “You’re not the little Mexican who walks around with his tail between his legs apologizing for being Mexican and asking permission to get a driver’s license.” That kind of validation and approval has meant more to me than anything.

Here’s something else Miles told me: “I’m more than just a little guy playing some blues.” I feel the same way. I’m all the animals in the zoo, not just the penguins. I’m all the races, not just Mexican. The more I develop spiritually, the less nationalistic I am about Mexico, the United States, or anywhere else.

I am sure a lot of people get pissed off. “You’re forgetting your roots. You’re not a Mexican anymore.” But I am still working out my own identity, crystallizing my existence, so that I can be more consistent in saying I am proud to be a human being on this planet, no matter what language I am speaking or what country is collecting taxes from me. I came from the light, and I’m going to return to the light.

Those statues of the Virgin had a very special look to them—you could recognize them right away. After Santana hit it big and we began to tour the world, I would come across those Virgins in America and in Europe—even once in Japan. Somebody had been to Tijuana and bought one and brought it home. It was like seeing an old friend again.

The trip from Autlán to Tijuana took place in August of 1955, just after my birthday, and we traveled for almost five days. It took a long time to get there because not all the roads were paved. I remember that each of those days felt like a week. It was hot, and we were cramped against each other in the car, and it didn’t get much better when we stopped. Barranquilla was crabby and grumpy, complaining the whole time. My mom would say, “I ain’t got time for that, you know? Take it up with José.”

There weren’t any hotels or motels along the way, and even if there had been, we didn’t have money for anything but gas. We slept in the desert under the stars, worried about scorpions and snakes. The food ran out. So every time we stopped somewhere, Mom would try to buy something that we could eat. We had to eat at truck stops, where the food was horrible. I have never smelled or tasted beans that were so rancid. How can somebody screw up beans? I still can’t understand that—it’s like messing up granola. There were these ugly frijoles, and we kids were getting sick left and right. So we drank a lot of Kern’s canned juices. I can still taste that sandpaperlike sap. To this day I don’t want to see another one of those juices ever again.

I can still hear the music from the radio on that trip—especially Pedro Vargas. He had the baddest trumpet players at the time—they could play high and clean, like Mexicans. All his songs were romantic. What they were really about was sex.

We came to a big river, and we had to put the car on a raft that was just a bunch of planks. Then people would pull the rope from the other shore to get us across. I remember Barranquilla told us there had been rain upriver the night before and that the river was going to swell up, so if we didn’t leave right then it’d be another three days before we could even think of getting across. Man, it was scary. The water was already starting to get rough, but my mom decided we had to go.

We got into Tijuana around two thirty in the afternoon. Mom had the return address on my dad’s letter. The car pulled up, and my brother Tony remembers that he and my mom got out of the car alone and told us to wait. My memory is that we all stumbled out of the car, tired, hungry, and cranky. Either way, I know we all needed baths badly. Mom knocked on the door, and nobody answered. She knocked again, and a woman answered. It was pretty clear, as I look back on it, that she was a prostitute.

To be honest I didn’t know what a prostitute was, or a floozy, or anything like that. I didn’t even know the words yet. Later on I would figure it out. But she looked like something the cat dragged in, and I knew enough to know that she wasn’t someone like my mom. My mom carried herself very differently.

This woman started screaming at my mom. “What do you want?” My mom stood up to her: “I want to talk to my husband, José. These are his children.”

“Ain’t no José here.”

Bam! She slammed the door. My mom just broke down crying. I still feel it in my gut. Mom was crying and getting ready to leave and give up, and we were all wondering what would happen to us. We could see it in each other’s eyes.

It was time for another angel to appear—someone in the right place at the right time, guiding us and saying, “Don’t quit.” This time it came in the form of a wino who was lying next to the building, asleep. He woke up because of all the commotion and asked, “What’s going on?”

“I’m looking for my husband, José, and this is the only address I have,” my mom said.

“You got a picture of him?”

She showed him a photo, and he said, “Oh, yes. He’s inside.”

So Mom knocked on the door again. The lady came out again, screaming. And this time all the screaming woke up my dad. He came out, and I was the first thing he saw. Then he saw everyone else, and I saw his face starting to look like a bowl of M&M’s. I mean, all the colors in the rainbow: red, blue, yellow, green. His face went through all the emotions and all the colors.

Dad grabbed my mom by the arm and asked, “Woman, what are you doing here?”

“Don’t grab me like that!” And they started into it.

I’m amazed every time I think about the pure, steel-like conviction my mom had. She would not be deterred, even when her friends and family told her that she was crazy to do this, that she didn’t know what was going on in Tijuana. “You’re crazy—what if he doesn’t take you back?”

“Oh, he’s going to take me back. If he’s not, he’s got to look me in the eye and say that—and look in his children’s eyes.”

Dad got hold of somebody he knew and found a place for us to stay. They were building a house that didn’t have any windows or doors yet, and it was way up in the worst part of town, Colonia Libertad—ghetto, ghetto, ghetto. That neighborhood is still there. We had gone from the ghetto in Autlán to the ghetto in Tijuana. At first my dad wasn’t staying with us. My mom was pissed. He would come and visit us and bring a bag of groceries, but he would only stay for a short time.

Eventually Dad left the other woman, and we were all together again. Later on we started moving up, living in better places with electricity and plumbing, but I remember that the summer of 1955 was so hot we couldn’t even sleep. We were tired and cranky all the time. We had no money at all. We were hungry. There were fields nearby filled with big tomatoes and watermelons, and at night we kids would go and gorge ourselves. I think the owners looked the other way because they knew we were hungry.

My mom and all the other ladies in that part of Colonia Libertad did their washing using water from one particular well. They would haul these big cubas—laundry tubs filled with dirty clothes—and work those washboards. The well was so deep that the water had a sulfuric smell to it. One time I suddenly realized something: we didn’t have plumbing—we should have plumbing. If we did, Mom wouldn’t be washing clothes outside, using dirty water. I said, “Mom, someday when I grow up I’m going to get you your own house and a refrigerator and a washing machine.” She just kept washing and patted me on the head. “That’s nice, mijo, that’s really nice.”

“Hey! Don’t dismiss me like that,” I was thinking. “I am going to do it.” Of course I didn’t know then how I was going to do it; I was still just eight years old. But I made a promise—to my mom and to myself. As it turned out, it only took fifteen years. It felt so good when it came to be in 1970. I did it with my very first royalty check from the first Santana album. Even after everybody took a cut—the accountants, managers, lawyers—there was enough to keep my promise. I know it made her and my dad really happy. That was the first time they started looking at me like I wasn’t so crazy after all. They thought I had lost it after smoking all that weed and hanging around the hippies. To this day I can’t think of them in their own house in San Francisco without thinking about that disgusting well. It still feels good that I was able to come through.

Despite the circumstances, it was actually a nice transition from small-town Autlán to Tijuana. It was new, exciting, and different. I have great memories of learning to play marbles. My brother Tony taught me; he was really good with them. They looked like diamonds to me—I used to hold them up to the sun and look at them sparkle.

The tastes of Tijuana were a change from those of Autlán, because as I started to grow up my tastes were changing, too—from sweet to savory. There was pozole, a stew that my mom always ate when she was pregnant—that and tamales. There was mole sauce—which is like chocolate, just not sweet—and pipián sauce, more orangey and made from pumpkin seeds. Man, she could stretch the chicken with those sauces. She was great with shrimp and chiles rellenos, which are fried with cheese inside and batter outside—very few people know how to make it so it doesn’t get soggy and weird. My mom had that down, and she was an expert with machaca—shredded beef with eggs and so much spice that you’d get a good heat going. Wash it down with agua de Jamaica, which is made out of hibiscus petals and tastes like cranberry juice, only better.

I also remember that I started hearing more music than I had ever heard before. Right across the street was a restaurant with a very loud jukebox. It sounded like we were just one room over. That was the summer of Pérez Prado—“Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White.” He was Cuban but moved to Mexico. A lot of Cubans came over, and they’d record and get big in Mexico City, then humongous all over. Those mambos sounded so good. It was like an ocean of trumpets.

In the middle of the 1950s, Tijuana was a city with two sides to it—depending on which way you came into town. If you were American and drove south, it was Fun City, another Las Vegas. It had nightclubs and racetracks, late nights and gambling. It’s where the soldiers and sailors from San Diego and all the actors from Hollywood went to party. Tijuana had nice hotels and five-star restaurants—like the one in the Hotel Caesar, where they invented the Caesar salad.

For those of us heading north into town, Tijuana might as well have been the United States. It didn’t matter that we hadn’t crossed the border. There was a flavor of America, and a lot of Americans were always there, walking down our streets in nice suits and new shoes, making us think of what it was like just across the border.

The streets of Tijuana were not like those of Autlán. Autlán was the country as far as the ways people thought and treated each other were concerned. Tijuana was the city, and you could immediately feel a difference. People were drunk, angry, or upset about something at all times of the day. I soon started to learn that there was a way to walk those streets—a different kind of walk. Without disturbing anybody, you could project an attitude of “Don’t mess with me.” You don’t want anybody to mess with you there. When I got older and people would tell me about tough neighborhoods in Philadelphia or the Bronx, I would say, fuck that. That ain’t nothing compared to Tijuana. There’s a code of survival there that you learn very quickly.

You realize it’s true what they say—don’t mess with the quiet ones. They were the most dangerous. The ones that shot off their mouths—I’m going to do this or do that—they didn’t do shit. I also learned you didn’t want to mess with the Indians or mestizos. The cholos and pachucos might pull a switchblade. But those Indians would whip out a machete and could chop up a body like it was a banana.

I saw it almost happen one time just after we got to Tijuana, right outside of church. The machete hit the ground when one guy missed chopping another guy’s leg off. Sparks flew off the street when the blade hit it. You don’t forget stuff like that—the sound or the sparks. It was scary. Next thing, the police came over and started shooting in the air to break up the fight before the men did some damage. I realized that this was not a movie. This was real life, man. I also learned that very seldom was the fight about money; it was almost always about a woman.

I don’t remember being hassled at all in Autlán. We kids had to fight more in Tijuana. The good thing was that it was more about bullies than gangs. The gangs would come later, after I left. Bullies used to pick on me, and looking back on it I see that it wasn’t personal. It was just that ignorance is ignorance, and the hood was nasty. I had to be able to know when to walk away and know when to hold my ground so they didn’t keep piling up on me. I learned that if they thought I was crazier than they were, they would rather go around me. A few times I had to do that—fight and act crazy. It got to the point where I would find a rock that was the size and shape of an egg, and if things got weird I would put it in between my fingers and get ready to punch.

At the time I looked a lot different from the way I look now. I had fair hair and was light-skinned, and my mom dressed me like I was a little sailor kid. I mean, come on—of course I was going to get into fights. One time I got to school—Escuela Miguel F. Martinez—just after my mom had spanked me for some reason, and I had a lot of anger in me. Sure enough, some guy said something like, “Look at this guy! You can tell his mama dresses him.” I had the rock in my hand, and I nailed him hard! Everybody was standing around, waiting to see what he was going to do. I was looking at him like, “I hope you try to do something, because I’m ready to die.” There’s two kinds of desperation: one is born of fear and one is born of anger, and in the one born of anger you just don’t want to take it anymore. I forget his name, and I didn’t realize then that he was one of the street bullies. He never bothered me again.

The thing is, he was right—my mom was dressing me. I used to tell her, “I’m getting beat up in school; you got me in short blue pants and stuff. This is like saying, ‘Come and get me.’”

“Oh, you look so nice,” she’d say.

“Nice? You’re dressing me like a choirboy. Mom, you don’t understand.”

“Shut up!”

Once my mother wanted me to wear some pants I didn’t like. She got angry and said, “You’re like a crab. You’re trying to straighten everybody else out, but you’re the one who always walks crooked.” That stayed with me. I said to myself, “I’m no crab, and now there’s no way I am going to wear those pants.”

It took a while to convince my mom, and I talked to my dad to help me out. Slowly they came around. They were so involved in trying to make it to the next day, so concerned with food and getting the washing done—it wasn’t like we sat down to break bread and talk about these things. All of us kids had stuff like that to deal with, and we just had to get through it.

It was toughest on Tony. He was a teenager and new to town. And he was dark-skinned, but I was fair-skinned and had light hair back then. When we would go out together, they really picked on him a lot. “Hey, Tony, how much do they pay you?” He didn’t know yet to ignore them. He’d say, “Who pays me for what?”

“Aren’t you babysitting that kid?”

“No. He’s my brother.”

“No, he ain’t—look at you. He doesn’t look like he’s part of you!” They’d start laughing, and he had to answer them somehow, and the fists would start flying.

The worst that happened was a few years after that, when Tony got hit in the head with a hammer in some street brawl. He told us that he could have avoided it, but his friend wanted to come home the same way they had gone into town, back on the same street where they had gotten into an argument with some guys. He survived, but that was what it was like. Welcome to Tijuana.

I’m glad I’m not the oldest in my family. The ground was tested by Tony, Laura, and Irma before I came along, and whatever was going on with Mom and Dad, Toño—that’s what we called him—got the brunt of it. He got the main bruises because my mom and dad didn’t know yet how best to deal with kids. He was like my buffer and second father and has always been in my corner—my first defender and my first hero. I’ll always be so proud of him.

I love my family, man. They’re all so different, each one of my sisters and brothers. Laura, she was in charge when my mom and Tony weren’t around, since she was the oldest girl. She was like the scout and would be the first to check things out when we moved into a new place—very curious and mischievous. She was an instigator, too, like, “Let’s cut school and go get some jicamas!” Or “Let’s go pull some carrots out of the ground and eat them!” Like I needed convincing. “Sure, okay—sounds good to me.”

I remember one time Laura decided to get some candy on credit from a store, and she shared it with all of us. When my mother found out about it, there was hell to pay—for all of us. I wasn’t even there when all this went down, but when I got home there was another beating waiting for me. That was what Laura was like—a troublemaker and fearless! Irma was more introverted than Tony and Laura, more on her own planet, and she also was the first of us kids to get into music. She told me that she used to peek into the room where our dad would be practicing his violin until he said, “Venga”—come here. He started teaching her songs and some piano, how to read music. She was a natural.

In Tijuana, the rest of my sisters and brothers were all small and growing up—Leticia, Jorge, and Maria. I didn’t get as much of a chance to babysit or take care of them, as Tony and Laura had done for me. I feel especially bad for Jorge that I wasn’t as much a big brother for him as Tony was for me. He would have to figure out a lot of things on his own. After we left Autlán, I was either out on the streets or hanging with Dad.

From the moment we got to Tijuana, we started to learn to survive another way, too—it was time for all of us to go to work, to start supporting the family. All hands on deck, you know? I give the credit to my mom and my dad for all that. They implanted in us some really no-nonsense, hard-core values and morals. You never borrow or beg. What doesn’t belong to you, you don’t take. What’s yours, you fight to the death for it.

One day when my father woke us up, he had with him a couple of boxes of Wrigley’s spearmint gum and a shoe-shine box. He gave half the gum to Tony and half to me, and he gave the shoe-shine box to Tony. “Go down to Avenida Revolución, and don’t come back till you sell all of it,” he said.

Avenida Revolución was our Broadway, the center of downtown Tijuana, where the bars and nightclubs were and where all the tourists went—American and Mexican. Tony and I would go up to them, selling gum and shining shoes. That was really the beginning of my introduction to American culture. It was the first time I saw a black man—a really tall dude with big feet. I just stared at the size of his shoes while polishing them. I began to learn a few words in English, and I learned to count. “Candy, mister?” “Ten cents.” “A quarter.” Fifty cents, if I was lucky.

We would get just enough money to take the bus, so we had to make enough money to pay for our inventory and supplies plus enough to ride home and get there the next day. Sometimes we ended up walking because we had no bus fare—like the time Tony got a huge fifty-cent tip on a shoeshine and we decided to take the rest of the day off. We were rich for an afternoon, watching a movie and eating candy, but we forgot to save something for the ride home. The next day, it was back to the same schedule—wake up early, help out at home, go to school, take the bus downtown, and sell, sell, sell—help Mom and Dad with the rent.

I think I did miss out on a certain part of my childhood, as many kids do. In the first ten years I was with my first wife, Deborah, I would sneak into toy stores and buy little figurines, action figures. Thing is, a few years after that, in 1986, I was hanging out with Miles’s drummer, Tony Williams. He started his career as a teenager, and I saw that his house was full of toys that he got from Japan—the first Transformers and all that. He saw me looking at them, and I said, “It’s okay; I do the same thing.”

“You do?”

“Yeah. What’s this one do?” Suddenly it was not the same guy who played at Slug’s with Larry Young and John McLaughlin or who drove Miles’s band in the ’60s. It was, “Oh, man, look at this!”

I’ll tell you, that was a revelation to me. I think Michael Jackson was like that also. There was part of us that missed out on being a kid, and we didn’t wean it out of our systems till much later. After a while, you grow up and put the toys away, but for a while that child needed to be expressed. I’m sure Deborah must have thought I was a peculiar dude.

What I went through was what all we Santanas went through. Everybody worked. After we were old enough to take care of ourselves, Chepa left (plus we couldn’t afford her anymore), and Mom needed help to run the house, clean, and cook. So Laura and Irma helped Mom at home. All of us did whatever we needed to do to make the rent and get the food on the table. That part of my childhood I’m really proud of—nobody ever complained or asked, “Why do I have to do this?” or anything like that. It was just understood.

We moved a lot during those first two years—it felt like almost every three months we moved to another place in Colonia Libertad. Then we moved across the Tijuana River, which runs right through the middle of the ghetto and into the United States, to a small place on Calle Coahuila, in Zona Norte, a neighborhood that was a little better. Two years after we came to Tijuana, we moved to Calle H. These were bungalows, almost like a trailer park. I was ten years old, and I noticed people around us had little black-and-white TVs. We kids used to sneak around to the neighbors’ houses and stand on our tippy-toes, peeking in their windows until—snap!—they closed the curtains. That’s how I discovered boxing. It was funny—I remember every few months there was a matchup between Sugar Ray Robinson and Rocky Graziano—on TV, in the headlines. And there was my first hero hero: Gaspar “El Indio” Ortega.

Ortega was a welterweight and was the first boxer to come out of Mexico and go all the way up. His hometown was Tijuana, so as you can imagine the whole place talked about him and supported him. We followed every one of his fights, especially the one in ’61, when he fought Emile Griffith and lost. It didn’t matter—he was our hero.

Ortega was one of the first boxers to be very evasive in his fighting. He knew how to bob and weave. Years later I got my chance to meet him—he was living in Connecticut then and had to be in his eighties. He was proud of his fights, but he was proudest of one thing. “You know what, Carlos?” he told me. “I still got all my teeth. They never knocked them out.”

I can still remember those fights, watching them and getting down on my knees and praying for Ortega and for Sugar Ray. “Don’t let them beat him,” I would say and squeeze my eyes shut. That’s when I really learned to pray from the gut—when I first began to realize that God might be listening.

If it had been up to my mom I would have been doing my praying in a different place. As usual, my mom was diligent and relentless—“You’re going to do this and you’re going to do that.” One time she decided I had to go to church and learn to be a monaguillo, an altar boy. It’s all about ritual and regalia, learning where to be at the right time, grabbing the book when you’re supposed to. The very first time I was in a mass, there was this other boy who was training me—he had done it, like, five or six times—and I remember he was a jokester.

At one point this guy started cracking up. Then I started cracking up, and the more we got to laughing the angrier the priest got. Then the next thing I know, all the people in the church started laughing, too. I didn’t know what was so funny—I was just trying to keep it together. Then the priest picked up the chalice, and I tried to pass him the book at the same time—“Okay, here it is; now read it.” The boy didn’t tell me exactly what I needed to do—I didn’t know you’re not supposed to give it directly to him. You’re supposed to put it in a certain place, and he’ll pick it up.

After the mass, the priest gave me a smack in the head. Of course that put a damper on my wanting to go to church ever again. I was thinking, “If you’re going to be with God, aren’t you supposed to be merciful and nice?” That priest single-handedly separated me from the church right there and then. I mean, what’s wrong with smiling and laughing in church? Are these not the things that God wants us to be doing—enjoying ourselves? I remember the Bible stories—the Flood; God asking someone to sacrifice his son. “Your God is an angry God; he’s a jealous God,” things like that. Come on, that’s not God—that’s Godzilla. I think God has a sense of humor. He has to.

I learned a few things in church—just the other day I made the gesture of a blessing onstage, like the one a priest would make over his sacred chalice, before I took a sip of wine. We were in Italy, so I figured everyone there would get what I was doing—the sign of the cross, hands like they’re praying, look up to heaven before raising the glass, which these days is usually Silver Oak Cabernet. I didn’t think it was sacrilege. I think any kind of spiritual path should have some humor.

Still, my mom persisted and persisted—two years after I got smacked in the head for laughing in church she was still trying to get me to go back there. She dragged me to confession at five in the afternoon. “We’re going there, and you’re going to tell the priest your sins.” I was twelve at that point. “What sins, Mom?”

“You know what I’m talking about!” She wouldn’t let go of me, and she had a strong grip. I’m young and I’m pissed, and I’m feeling guilty because you’re not supposed to be angry at your mother—that’s enough sins right there!

So we went to the church, and the little door opened, and I went in. I heard this voice on the other side of the wall say, “Go ahead, tell me your sins… go ahead… go ahead!” I didn’t know what to say, so I finally thought, “The hell with this,” and I ran out. My mom was so pissed. I told her the story of being smacked as a choirboy and reminded her that she didn’t want to hear about that. I told her that if God can hear me, I’ll talk with him directly, and that’s it. “You can make me do a lot of things, but you can’t make me do this, because I won’t do it.”

Nothing infuriated my mom more than her children standing up to her. That really pissed her off, and for some reason I was the only one who would argue with her. Everybody else just tucked in and took it. I was getting bigger, but she still would try to beat me. She was right-handed, and by then I had figured out that when she grabbed the belt—or extension cord or anything she could find—to swing at me, if I ran toward the left she would hit nothing but air. My sisters and brothers would start cracking up, which only made her angrier. I would get out of her grip and get out the door like a jackrabbit.

I would run away—I did it three times in Autlán and at least seven times in Tijuana. Then my brother Tony would have to come find me and bring me back. “When are you going to stop doing this?” he would say.

“When she stops hitting me.”

“You just don’t know the stuff she’s going through.”

“Yeah, but she doesn’t have to take it out on me!”

I remember wandering around Tijuana after one fight. It was Christmastime, and I was looking at window displays—little trains and toys and puppets, all that stuff. For years after that, every time I saw Christmas decorations those feelings would come up. All that anger and frustration I had toward my mom stayed with me.

My mom had her own special relationship with God, her own way of getting him on her side. When she needed something for the family, or when she thought something needed to happen, she would sit in a chair, cross her legs, fold her arms, and put all her focus on something far away. You could feel the determination. As kids, we got to know that look of supreme conviction. It was like, “Uh-oh, get out of the way—Mom’s doing that thing.” If we got close, we could hear her saying to herself, “God is going to give me this.” It was like she was willing a miracle to happen. “I know this will happen. God will make it happen.”

They weren’t big things: money for food, a better home for the family, health stuff. One time my youngest sister, Maria, was having trouble conceiving a baby. She had polio as a child, and her husband had just undergone an operation for testicular cancer. It looked like it was just not going to happen. Every time we would visit, my mom would be in her chair, folded in on herself, with that look of 100 percent determination, talking to God, until she told my sister, “You should adopt a baby, and as soon as you do you’re going to get pregnant.”

“Mom, what is wrong with you?” my sister said. “I can’t get pregnant—a bunch of doctors told me.”

“Yeah? What do they know? They’re not God. Do what I tell you.” Maria went ahead and adopted a baby boy, Erik, from a Mexican mother and German father.

A year later I was in Dallas at a festival with Buddy Guy and Miles Davis. We were all in the hotel lobby, and a phone call came in—“Paging Mr. Santana!” It was my wife, Deborah. “You’re not going to believe this, but your sister is pregnant.”

“Which one?”

“Maria!” She called her baby Adam—we all called him the miracle baby.

My mom would go to church in the middle of the week, when everybody was making confession, and bring a couple of big bottles of water. She patiently waited for the last person to finish, then she would go up to the confessional, and the priest would say, “Yes? Would you like to confess?”

“No, Padre, I’m all right now, but can you bless these bottles of water?”

“The holy water’s over there.”

My mom would say, “I’m sorry, Padre, I don’t want that water for my kids. Está mugre—that’s dirty. It’s filled with everybody’s germs and sins. No. Bless this for me. It’s for my kids.”

Then she would bring those blessed bottles home, and suddenly she was like, “Mijo, how you doing?” Touching us, running her hands over us. “Hey, Mom, you’re getting me all wet!” That’s the way she approached her beliefs and how she went through life. She did things that made sense to her, for the family, with no sense of doubt or shame. When she decided on something, we knew not to get in her way—we didn’t expect her to explain herself, and we didn’t expect her to get lovey-dovey.

I think my mom went through her life hiding a lot of pain. She had my dad to deal with, and she lost four babies. She rarely opened up, and I’m not sure she ever addressed those things consciously. In her solitude, when nobody was looking, she might have licked her wounds and cried for the children who died. But she never shared her suffering with us. She knew the difference between self-pity and its opposite—healing herself and moving on, restoring herself by looking at her suffering in the right light.

The last time my mom got pregnant in Tijuana she got really ill. I remember I was around eleven. We were living in a place where we used a packing crate as a front step to get into the house, and my mom slipped on that, fell down, and lost the baby. The ambulance came and took her away.

My mom told us later that when she woke up in the clinic there, she got the feeling that this was not a place to get better but a place to die. Nobody was paying attention to her or the other patients. People were dying to the left and right, and she could feel life leaving her. So she pulled out the lines and tubes and whatever they had in her, got up, walked home in her robe, and fucking fought for her life. She was not going to die in that place. She was not going to die at all.

My mom was alone through a lot of this. Because of the culture and who my dad was, she could not lean on him for help. In Spanish we say, “Ser acomedido”—be accommodating, make yourself useful. Don’t be a bump on a log. If you see that you can pitch in and help, do it. Even if you’re a man, it’s okay to wash your own dishes—you’re not gimped, you can help your partner. But that never happened. She was on her own.

It made her strong and independent. But I think it also made her harder than she needed to be. I remember not long after she lost the baby, she was outside talking to a neighbor, and I heard her mention my name. You know how you hear your name in the middle of someone else’s conversation and your ears prick up? I heard my mom say, “Carlos es diferente.” She saw me looking and told me to come to her.

She told me, “Sentarte,” so I sat down on her knee as she wanted me to. Suddenly—pow!—she smacked me right across the side of my head. She did it so hard my ear was going eeeeeee, just ringing! I jumped up and was glaring at her with my mouth open. I just looked at her and she looked at me, and she said, “If you could, you would, huh?” Which meant, “If you could slug me, you would, right?” I just looked at her like, “Don’t ever do that again.” Then she looked at the neighbor. “See? The other ones don’t do that.”

That was cruel and that was ignorant. I wasn’t a toddler anymore. Why would she do that? Just to make a point with the neighbor—am I a guinea pig or something? I think part of the reason for it may have been her anger against my dad, and she took it out on me. He showed a blatant favoritism toward me. Maybe she was jealous; I don’t know.

The ringing in my ear was still going on minutes later. Something had broken between my mom and me that would take years to heal. She and I became rivals. I would buy her a house, but I would not invite her to my wedding. Not until Salvador was born did I start letting my mom back inside my heart and my psyche.

Yes, I was hardheaded. Just as she was. I guess “hardheaded” is the best way to describe it, or you can call it conviction. I’ve read that a person’s cells continue a pattern of emotion from one generation to another, that you can inherit a pattern of resentment or remorse. You can try to stop yourself from doing certain things, but you wind up asking yourself, “Why did I just say that? Why did I do that? Why can’t I stop myself?” That’s one reason I read spiritual books—to get answers that can help me separate the light, compassion, and wisdom from behavior patterns. It can be scary—it’s like letting go of something that is ugly, but it’s who you think you are.

When I became a dad, I let my kids know I loved them all the time. I still tell them, “You don’t need to audition for me. You passed the audition when you were born. I was there when you came out, all three of you, and you opened your eyes. You passed the audition.” The rest—how you’re going to use what has been given to you—is up to you. And I’m not afraid to say, “Come here, man, I need a big old juicy kiss and a hug. I need a second hug because the first one is just courtesy and the second one is long and ahh…” It can get mushy.

Everything changed with my mother when Salvador was born. All of a sudden, she was hugging him as a mother does. It surprised all of us. It changed me, too, and started to give me a stability that I didn’t know I had lost. I could be anywhere in the world at any time, and I would pick up the phone and call Mom: “Hey, how you doing? I’ve been thinking about you all day.”

“Yeah, I know,” she would say. “Because I was asking you to call me.”

Validating my parents was not easy, and it took a lot of work. Part of it is constantly correcting the psyche, freeing myself from what has been put upon me by other people, including my parents. There’s nothing like being in a moment of clarity to let all that stuff fall way. But the worst thing you can say is, “Hey, I forgive you.” I made that mistake just one time. My mom looked at me with this expression and said, “What do you have to forgive me about?”

“Oh, nothing,” I replied, and I changed the subject. In that one look I got her point of view. I didn’t have anything to forgive her for. Not when I had so many things to thank her for.

Around 1956, just as my dad’s father did with him, my father decided it was time for me to learn an instrument. He never really told me what motivated him to get me started, but I knew. Part of it was a family tradition, and part of it was to have something else that could put food on the table. Also he loved keeping me busy. I know he had tried to get Tony to play an instrument, but it just wasn’t part of my brother’s constitution. Tony had a mechanical mind and was really good with numbers. Laura was not inclined that way, either. Irma liked to sing, and Dad was already teaching her songs. Now it was my turn.

I remember the first time my father pulled me away from my brothers and sisters to show me something about music. “Ven aquí,” he said, and he took me out to the backyard. The sun was setting, and everything looked golden. He very carefully opened his violin case, took the instrument out, and put it underneath his chin. “Hijo, quiero mostrarte algo”—I want to show you something. “Estás viendo?”—Are you watching?

“Sí, Papa.”

Then he started pulling the bow across the violin very slowly, playing these little sounds, and out of nowhere a bird flew down and landed on a branch right next to us. It was looking at my dad, twisting its head, and then it started singing with the violin!

I was thinking, “Damn!”—or whatever word I had in my head when I was nine years old. He kept playing and looking at me, watching my reaction, not looking at the bird. They traded some licks for a while, then he stopped, and the bird flew away. My mouth was just hanging open. It was as if I suddenly found out my father was a great wizard like Merlin, and now he was going to teach his son how to communicate with nature. Only this wasn’t magic—it was music.

“Si puedo hacer que un pájaro, puede hacerlo con la gente, sí?”—If I can do this with a bird, you can do this with people—got it?

“Sí, Papa.”

I was nine when my dad put me in a music school that I went to every day after regular school. Originally I wanted to play saxophone—but I would have had to learn clarinet for a year first, and I was young and wanted to shout and scream! My dad tried to teach me to play violin, but it was too difficult. Then he tried to get me to learn the córneo, the same instrument my grandfather had played. I hated the taste of brass on my lips, but at the same time it was my dad. I couldn’t say no, so I tried to stick with it—I really did. After he finished teaching me what to do with my lips and the fingering, and how to clean the instrument with brass cleaner, eventually he realized that I didn’t have a love for the horn, so we went back to a small violin—three-quarter size.

My dad was my primary teacher. He would show me a melody and have me play it over and over. “Slow it down!” he would say. “Again, slower!” That used to drive me bananas, but it not only made me remember the mechanics, it also imprinted the music in me. I was learning tunes such as the William Tell overture, Beethoven’s Minuet in G, von Suppé’s Poet and Peasant overture, Hungarian gypsy music, Mozart, Brahms—all with sheet music. I was a clever fool. I learned to memorize a melody and pretend I was reading it. My dad would be busy shaving or doing something and see me looking at the paper. Years later I was in the studio, and Joe Zawinul saw me figuring out some music—“Do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti…” He laughed. “Oh, you’re one of those!”

I would say to myself that I would show my dad how good I could be and practice a song so I knew it cold. “I’m going to learn this.” Stroke, stroke, stroke. Again—stroke, stroke. “Got it, here he comes…” I’d play it for him, and he’d say, “Bueno, campeón.” He’d call me “champion.” “You really know this one. Now here’s one for tomorrow.” Man. I thought I was going to get a reprieve, maybe some time to go play with the other kids, hang out with Tony, or play hide-and-seek with Rosa from down the street because I heard she was okay with kissing and stuff like that. But I couldn’t get ahead of him. By the time I finished the lesson everyone had gone home.

My dad knew how to be effective with music, how to own it—and that was maybe the most valuable thing he taught me. It helped to realize on my own that the violin could be a very demonstrative instrument, very emotional. I realized how to put my finger on the string and how much pressure to put on the bow so it had personality—stroke, stroke—then add a little more tension, like you’re nudging somebody awake. “Mmm…” Nobody can teach you how to develop a personal expression. The only way is to work it out with yourself in your room. The most my parents were able to do was ask me to please just close the door.

My dad was a good teacher, but he wasn’t necessarily gentle. He would push me, and then the shouting would come, and I would start crying. I don’t mean to be melodramatic, but the salt from all those tears started discoloring part of the violin. I just wanted to try to please my dad, and in my mind it all went together—the way the wood smelled, the way the strings sounded, the feeling of frustration.

It wasn’t long before my mom stepped in. “You’re breaking his heart, José. He shouldn’t learn music like that—it’s just too brutal.” She had seen Tony run away from playing music for the same reason. “We don’t have too much money, but why don’t you take a break from teaching Carlos and have somebody else do it?” My dad acceded to my mom’s request and found me a teacher—actually two guys. One was big, like linebacker big, and the other was older. I started going to their houses, which were nearby, to get tips on holding the bow and other things. They were both really good at showing me stuff, helping me build my character, and reaffirming the good things I was doing, which was the opposite of what Dad was doing.

Here’s a story about one of those violin lessons. One time I was at the older guy’s house, and he and his wife were arguing about something in the kitchen, and I was bored sitting there on the sofa. My hands started to go between the cushions and I started feeling coins in there! Sure enough, I found almost two dollars—which was a lot of money for a nine-year-old in 1956. I quickly put the coins in my pocket, I did my lesson, and when I got half a block away I ran right to the store and spent all the money on M&M’s. The guy looked at me as if I were crazy. When I got home, my mom was hanging clothes on the line to dry, so I had the house to myself. I went inside, spread them all out on the bed, and separated them all by color. Then I ate them—first the green ones, then red, then yellow, then brown. I couldn’t stop.

It took me a while to like chocolate again after that. And when my mom found out what I did, of course she scolded me. “We don’t have any money, and you spent it on M&M’s? And you didn’t even share them with your brothers and sisters?” She didn’t spank me that time, but it was clear that she was less angry about my wasting money on candy than she was about my not giving any to my siblings. For her, it was always about sharing what you have with the whole family. That was the lesson that chocolate and money taught me—I think it freed me from thinking only about myself at a very young age.

Feeling the music was the first lesson, but money was a big part of it for my dad. He persuaded me to join up with two brothers who both played acoustic guitars, go out on the street, and make some money. I can’t remember their names, and we didn’t have a name for ourselves, but they were good. They knew the right chords, the right rhythms, and I had to really pay attention to keep up with them. I remember we had a big repertoire and could get the attention of the tourists. We would walk up and down Avenida Revolución, or take a bus to Tecate or Ensenada, and approach people. “Song, mister? Fifty cents a song.”

They would look at us, and we looked young. “Can you actually play those things?”

“Sí, señor.”

We’d play the obvious favorites, like “La Cucaracha” and “Bésame Mucho.”

We were good, and it was a good experience—my first band. Every experience has its lessons. For me, this one began with learning to deal with band members. They were brothers, but they couldn’t have been more different, and they were always arguing. I think they must have had different fathers. I also learned about eating other people’s cooking, because a lot of places where we played would feed us—chicken tacos, enchiladas. It was good, and it was different from my mother’s cooking.

But one of the best lessons I learned from working with those two was how to carry a melody—how important that is on any instrument, an absolute must. It was like learning how to walk with a glass of water, carefully, without spilling a drop, from way over there to this point here. I would find out later that a lot of guys really can’t carry a melody, and if you can’t do that I think you should just find something else to do. Every musician I love can do that, no problem. When a musician can do that one simple thing, he’s going to nourish people’s hearts and not tax their brains.

The other thing I got from playing with the brothers was confidence. I started to feel good about my playing and about doing it in public.

My father saw this and started to enter me into little music contests around Tijuana—at street fairs and radio stations—and I started to win prizes such as food baskets, big bottles of Coca-Cola, and some fancy buttons, all of which I would immediately give to my mom. “Fascination” was the tune that I would kill with—all the ladies loved that one. Most of the time I competed with mariachi singers—but one time when I must have been thirteen or fourteen it ended up that my sister Irma and I were the only ones not eliminated at the end of a contest. She sang a doo-wop song, like “Angel Baby,” and I played my song and I got the bigger applause. “I don’t think your sister took it so well,” I remember my mom told me.

It was around this time that I started to feel very uncomfortable with favoritism, embarrassed by the amount of attention my dad would give me. I could feel the distance that it put between me and my siblings. It was something I came to resent and another pattern that followed me through the years—an uncomfortable feeling that would come over me when certain people, including Clive Davis, Miles Davis, and Sri Chinmoy, would show an obvious favoritism toward me. I would come to see Bill Graham in his office, and he’d ignore other people. “Tell him I’ll call him back—Carlos, how you doing?” Even my mom would do it—she’d hang huge pictures of Deborah, the kids, and me in her house, but there would be smaller—or no—pictures of my sisters, brothers, and their families. I tried to explain it to her. “Mom, this makes me uncomfortable, and it’s not fair.”

“Why? This is my house and my choice.”

I had to say, “Well, actually, it’s my house, Mom—I’m paying for it. Please either take down those big pictures or put up the same number of the rest of the family—please.” Finally she understood what I was telling her and took them down.

The more music I played, the more I could appreciate my father’s talent for doing it day in and out. He was a natural-born leader and kept things together—a no-nonsense kind of guy. He had stature in Tijuana. They knew him and associated him with Agustín Lara’s “Farolito,” so much so that it became a signature song. When he performed, people expected it, like people later expected Santana to play “Oye Como Va.”

Years later, I was working with my son, writing the song for my dad—“El Farol”—that we put on Supernatural. What else could we call it? That’s when I got a call from Deborah saying that I needed to call my family right away—somebody had left. “Who? Where’d they go?” I could tell from her voice what she meant. My dad died just as we finished putting that song together. I was equal parts proud and sad when it got a Grammy the next year.

My dad commanded respect without saying a word. I never saw him reprimand or correct or get upset with the musicians he worked with—but he wanted them to respect themselves, too. My dad would look the musicians up and down to see how they were dressed. If he saw someone wearing dirty shoes or a wrinkled shirt, he’d say, “Go home and come back, because you’ve got to be presentable, hermano.” He wanted them to want to look their best.

A lot of it was simply being willing to trust the other musicians, and they paid him the same compliment. He could walk into a room, and people would greet him. “Hola, Don José. How are you?” One time we walked in together when someone was telling a dirty joke, and they stopped immediately.

My dad knew his position, how to work hard. He’s the one who first told me, “Never pay or feed musicians before they play.”

“Really? Okay, Dad.”

In the early days, he would bring me with him to a place where he was playing and put a quarter in my hand so that I could get some candy or grapes—grapes were my favorite. Then he’d tell me where to sit. Soon he had me playing with his band on some shows.

There’s a photo from around this time of my dad and me with a bunch of musicians, all dressed up—we look like Don Corleone’s henchmen, you know? You can tell by the way we’re dressed that we were playing for somebody who had a lot of money, real hoity-toity, a high-society kind of gig for Tijuana. I remember that the occasion was something like a twenty-fifth anniversary, a one-time thing, not a regular band gig. We were playing waltzes and Italian ballads—no polkas or any kind of norteño music for that crowd.

It was during this time, around 1957, that I went to hear my father play one day and met an American tourist who became friendly with my parents. I think the best way to describe him is that he was a cowboy from Burlington, Vermont. He got close to me while my dad played, talking to me and keeping me company. He was a character, and as a youth I was fascinated with him and didn’t know better. Neither did my mom and dad. They couldn’t figure him out. At first they were suspicious of this gringo, but slowly he gained their trust. He showed up a few times after that and started buying me stuff like toy guns and holsters. Then he offered to take me with him across the border to visit San Diego.

What kid wouldn’t want to go? It would be my first time to America. My siblings and I were poor kids—we talked about America with wonderment, wondering what it would be like to cross the border and see the country. We knew about it from TV—Howdy Doody, the Little Rascals, and The Mickey Mouse Club. We could see America from our neighborhood in Tijuana—bright lights and nice buildings. San Ysidro was really just minutes across the border. It smelled different, I knew it. I wasn’t eleven yet, but I was ready to go.

My memories of what exactly happened are very sketchy, like old photographs more than a movie. Everything was going fine, then all of a sudden the man started molesting me. I’m not sure how many times it happened. I remember it sometimes happened in a car and sometimes in a motel room. It was just so sudden—there was the surprise of it happening and an intense feeling of pleasure mixed with confusion, shame, and guilt for letting it happen.

It was like not knowing the words to describe the prostitute who answered the door when we arrived in Tijuana. I didn’t know what to call what was happening to me when it happened—I didn’t even know that there were words for what the guy was doing. I could understand that there was an exchange happening—I do something for you, like buying you candy or toys, and you let me do something for my gratification.

But I had the feeling that something about it was very wrong. Then it was over until the next time. More candy, more toys. Later, when I learned what the word molest meant, I was able to describe it with the vocabulary of a grown man. But I wanted not to think about it—it was painful to remember. I was numb to it for many, many years, until I finally realized where a lot of my anger and negative energy were coming from.

The molesting ended for two reasons—first, my mom heard about his reputation from a friend, and she confronted me. She did it in front of the whole family, in a way that made me feel like I was on trial, as if it were my fault. Man, we didn’t have the wisdom to know how to talk about it. “Carlos, get over here! Did something happen to you? Did he do something?” I was just standing there with everyone looking at me. I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know the words! I was so ashamed and angry at the same time.

My father was silent about it, which I think was for the better, because there was no sense in attacking or killing the guy and then going off to jail with the rest of the family wondering, “What are we going to do now?”

That was the worst part of it—being angrier at my mom than at the guy who molested me, which only created more distance between her and me. It was a negative emotional pattern that took a long time to shed. One of the things I still regret is that I didn’t have someone at that time to sit me down and help me transform my anger, because it put a lot of distance between my mom and me. It was the reason I did not invite her to my wedding in 1973. I explained it to my in-laws by saying that she was a control freak and the event would be better without her. I would keep my distance from her for another ten years after that.

I know it hurt my mom a lot, too. Despite all those bad feelings, she turned out to be my best friend when it came to music, helping me in ways I didn’t even know about till years later.

The second reason the molesting stopped was that the cowboy found someone younger than I was and moved on. That was cool with me. A little while later he was driving in the car with some other kid, and the two of them were doing whatever they were doing, and they ended up crashing into a ditch. He became an invalid, collected some insurance, and moved out of Tijuana. That’s what I heard, anyway.

The whole thing had me growing up really fast, because I was thinking that this is not for me, this is a mistake, and I was starting to pay attention to a Chinese girl, Linda Wong, who lived near us. Her family owned a grocery store where we shopped, and I was totally fixated on her. So it all ended, and in my mind it was like it never happened.

Back in Tijuana I had to go to school; I had to go make money. I had to keep practicing the violin. By 1958 I had sold my last pack of gum and shined my last pair of shoes and started earning money exclusively from making music. I stayed with the violin for almost six years, on and off, from 1955 to 1961. During that time I was turning into a teenager. I was twelve when I saw Linda and had my first crush. She was thirteen but had the body of a twenty-year-old. She even smelled like an adult. I felt like I was eight when I was around her.

I was beginning to develop my own taste in music. There was a lot to choose from around me—the classical and dance music from Europe that my father taught me and the mariachi and other Mexican music that the tourists always asked for. There were rancheras from the country, cumbias from Colombia, and Afro-Caribbean clave music, which they called salsa and we called música tropical. There was the heavily orchestrated big band music that I first heard when I was trying to learn the córneo—music that I thought of when I heard the word jazz—which I associated with a dinner club in Tijuana called the Shangri-La. I called jazz Shangri-La music until Santana drummer Michael Shrieve introduced me to people like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Thelonious Monk and turned my head around. Then there was American pop music and doo-wop songs on the radio and TV and singers like Paul Anka and Elvis Presley, whom my sisters loved and I hated.

I was still working out what I liked, but I knew what I didn’t like, and a lot of it was stuff I heard at home. My mother liked big bands such as Duke Ellington’s—she really liked Duke, I later found out—and guys like Lawrence Welk. When she played that at home, I’d say, “I’ll be outside, Mom.” When she finished with the record player, then Elvis Presley ruled. My sisters would jump on the turntable with their Elvis records, then jump on me when I tried to leave. They would tackle me like they were football players and pin me to the floor, all four of them. The more I struggled, the more they’d tease me and scratch me. Part of me would be in agony, and the other part would be laughing, and my mom would hear us and come in. “Qué pasó?” Whoosh—they got off me. “What do you mean, ‘Nothing’? What happened to your neck, Carlos?”

Of course none of my sisters remembers anything about this at all. But to this day you won’t find any Elvis Presley records in my house.

It wasn’t that I didn’t like Elvis. I was just starting to know the music that Elvis liked—Ray Charles, Little Richard. Later on, after I started on guitar, I would discover B. B. King, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters—all the string benders. But back then, I was just opening the door for the first time, checking out this Americano music, and leaning in the direction of early rock and roll and rhythm and blues. I didn’t know enough to have a name for it yet—but my dad did.

“You want to play that freakin’ pachuco shit?” Calling it pachuco was like calling it delinquent music, and my dad was not happy about it. I was around twelve at the time. He had made me play with him at a bar in the worst part of Tijuana—it was like tourist hell. The tables were all black from cigarette burns and who knows what else; there were no ashtrays. There was a cop who was putting his hands all over a woman, and I could see that she couldn’t protest because she’d end up in jail. The whole place smelled like piss and puke—worse than Bourbon Street in New Orleans. They expected us to play norteño music—Mexican rancheras with polka beats that they play in border towns and across the border.

Back then I thought that this type of music was meant to drink beer and tequila to, to feel sorry for yourself to. I just never connected with it. It felt like wearing somebody else’s shoes. It wouldn’t go inside my body. Years later I would look back and say I hated mariachi music, but it really wasn’t about that—it was about my feelings. It was because this kind of music reminded me of painful, hard times with Mom and Dad, and it took me a while to look at it differently.

There’s so much that comes from Mexico that I love now that I know more about it—like those big mariachi orchestras with one hundred strings. Incredible. Or son jarocho, which is like flamenco but much funkier—just amazing. Ritchie Valens’s “La Bamba” is a jarocho rhythm brought into a rock-and-roll format. Then there are groups like Los Muñequitos de Matanzas—the little dolls. They’re Cuban, but their lyrics could be totally Mexican: “I’m in the corner at this cantina / Reminiscing about the one that got away / And I wait impatiently for my tequila.” Those guys are still around and huge in Mexico.

I was too young to pick up any of this at the time. I was more focused on practicing my violin lessons for my dad. But I learned later to be proud of all the great music that came from Mexico, or that came through it. There’s so much cross-pollination of music there—from Europe, Cuba, even Africa. But Cuba especially: the son, danzóns, boleros, rumbas. Back in the 1950s Mexico City was like Miami is today: the city where musicians from Central America and South America came to record and go viral. The Havana connection was tight—we had Toña La Negra, the singer Pedro Vargas, and Pérez Prado, of course, who was the most popular one. Mexico City had the studios and radio stations, and they had movies that needed sound tracks, and it was all on the doorstep to the United States.

I was just ten when I first saw the influence of Mexico north of the border. I remember my dad rented me a mariachi suit—size small, but still too big. Then he took me with his band to play in Pasadena, which was around a three-hour drive from Tijuana back in 1957. This was the night before the Rose Parade, so the whole town felt like it was ready for a party. We performed for Leo Carillo, the Mexican American actor who played Pancho in The Cisco Kid on TV. He had this big, lavish house—it was the first time I had been in a place like that. It felt like we were in a Doris Day movie!

Leo was very proud of his heritage—in fact, all Mexican people are really proud of their mariachi and their food and the tequila. I remember Leo was a very happy and gracious person. He had all this Mexican food spread out, and we played all night for his American friends. The whole thing felt good—Dad was proud of me.

But this joint on the other side of Tijuana was something else. It wasn’t just the music—it was the whole scene, because in fact we were playing in a place where the style of music didn’t even matter. Nobody was listening anyway. Most of the people were too drunk or too busy working their own hustle.

I had to answer my dad straight right then, man to man, when he started picking on my taste in music. “Look at where we are and what we’re playing. Could the music I like be worse?” He looked at me and didn’t try to hit or spank me. But he got really angry. “Leave. Go. You always have to have the last word. You are just like your mother.”

He wasn’t wrong. I’ve got my mom’s fire, and it still gets me in trouble. Sometimes I don’t know how to hold my tongue or my temper. Poor Mom—I’m blaming her. My dad was completely the opposite. I never really saw my dad lose it with me—get really angry or anything like that. Later on I realized my dad was an example of what I could work toward—catching myself if I felt I was going to snap. From him I tried to learn to be more considerate and more understanding and trusting. I can tell you for me it’s still an every-day thing. I think one of the truest things I ever heard was Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s observation that we are all a work in progress, a masterpiece of joy still being created.

My dad was the one with taste and practicality. He loved his Agustín Lara and European music, but he played mariachi music to feed us. He never said he didn’t like mariachi or norteño music, but I don’t think he could afford to, and I don’t think Tijuana was meeting our needs anyway. My mother was pushing him to find better opportunities—pushing him north again, just as she had done in Autlán. The next thing I knew he began to go to San Francisco to play. I remember going with him when he went to catch a bus across the border and saying good-bye.

Then he was gone, and I stopped playing the violin. I figured, “My dad’s not here to torture me, to make me play music that I don’t like.” I also never really liked the tone I got on the thing—it sounded corny, like some Jack Benny stuff. Many years later I was walking in Philadelphia, checking out a street festival with my friend Hal Miller, and I heard this young violinist. She could not have been older than fifteen, and she had the most amazing tone. Just lovely. I couldn’t move. I remember thinking if I had been able to get that kind of sound out of that instrument, there’d be one less electric guitarist playing today.

So I decided to give music a rest and play hide-and-seek with Rosa and just be normal with the rest of the kids. Of course my mother was not going to let that happen. She always had ideas—making plans, doing something. She was about to do something that would change my life.