CHAPTER 7

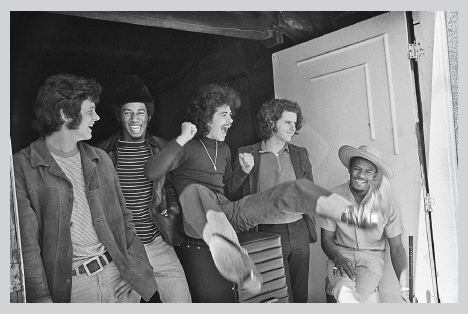

Santana in late 1968. (L to R) Gregg Rolie, David Brown, me, Doc Livingston, and Marcus Malone.

Before I was twenty, I could hear the difference between a weekend musician and a full-time musician. I could tell from a person’s playing if there was enough conviction to elevate the music, to make it come together. When I started playing with people I knew in high school, I could tell how the music changed depending on whom I was playing with. In our group we’d try out various tunes or keep old ones, but the songs we played were not as important as the new players who came into the band. I think I was lucky to have started so early in Tijuana—even the little group that had the two fighting brothers on guitar and me on violin helped me to hear what works and what doesn’t in a group situation.

I think if you look at rock groups in their first few years you find two ways they got their sound. Groups like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Grateful Dead mostly came up together. Their lineups changed very little; sometimes not at all. They got better together. I think Santana developed more like a jazz band does, with different musicians coming and going until the right parts are together and the music grows into itself. We also came from R & B and Latin music: our instruments were guitar, organ, and percussion—no horns. When we started we didn’t have a plan for what our sound would be like, but we knew it when we got it. I think Santana is still developing a sound that depends on the people who come into the band.

One thing we had in common with groups like the Dead and the Stones is that everyone in the band started as equals. Early on, these groups all were collectives. Then each band got tested and got successful until a leader had to step up.

I think it was a good thing Santana began that way. I think if it started out with my being the leader I might have wanted to do only whatever songs were already in my head, and maybe I wouldn’t have been open to hearing the music that we were developing. I would have tried too much to control what was happening. Even with the Santana Blues Band, the idea of letting the music lead the way was there at the beginning.

The summer of 1967 was the Summer of Love in most people’s minds. Flower power and psychedelic rock and hippie chicks. The Monterey Pop festival. Everybody was talking about how Jimi Hendrix burned his Strat and broke it onstage and How could he? Then Are You Experienced came out, and suddenly the sound of the electric guitar was dive-bombing, supersonic jets, roaring motorcycles, and rumbling earthquakes. Jimi made sonic sculptures out of feedback. Jimi’s first album took music from the days of gunpowder to the time of laser-guided missiles. I remember someone turning me on to “Red House,” and I knew immediately this was where electric blues were going—everybody was going to be following Jimi.

For me and many musicians, this was also when we started to feel that the resonance of our convictions could change the world. People like John Coltrane and John Lennon felt their music could be used to promote compassion and wisdom. It could make people better human beings. Later, Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, and Bob Marley did the same thing—“Amazing Grace,” “What’s Going On,” “One Love.” Their music infused people with a different kind of message that went beyond entertainment: “We are one!” It wasn’t just a cliché. It had real power to unite, just as Woodstock and Supernatural did. There can be unity, and music can be the glue. That’s the big message, the one I’ve been hearing and believing since I was a teenager.

For me, the summer of 1967 was also the summer of decisions.

One day I saw the Grateful Dead stop by the Tic Tock in a limousine. Everyone in the city knew they had signed a big record deal the year before and had their first album out. I saw them from the sink where I was washing dishes and said to myself, “I shouldn’t be doing this anymore.” It wasn’t because of the limousine. It was the idea of making a full commitment to music. I had to take the whole plunge—music had to be my 100 percent, my full-time thing. My office and my home. My eight days a week, as the Beatles said. Who you are going to be decides what you’re going to do, and what you’re going to do decides what you’re going to be. I was telling myself, “Dude, make the eight lie down like infinity.”

The decision to leave had been building up for a while. It was really motivated by seeing those Chicago blues guys playing the Fillmore in that first year. Man, I would be in such a daze for weeks after that, I don’t know how many dishes I broke at work. It seemed like they were calling me—calling me to abandon, as my good friend the saxophonist Wayne Shorter would say. Abandon the need to ask permission to do this or that, to live my life. I could hear the level of the commitment they had in their music; I could hear their commitment to the way they lived their lives. I could even smell it. The other decision I had to make was to finally leave home. I could not be like those bluesmen and still be living under my mother’s rules.

Then everything seemed to happen at once. We had showed up late to play the Fillmore and lost any chance at playing there again. A few days later Danny Haro’s brother-in-law was driving Danny’s green Corvette and crashed. He was the first person close to my age to suddenly die like that. Then I dropped LSD and had a bad trip. It wasn’t my first time tripping, but it was my first bad trip. A really bad trip.

The problem was that I was in the wrong environment when I dropped. First I dropped with a guy who started freaking out, which made me freak out a bit. Then I left him and was hanging with Danny and Gus in the house they were living in in Daly City. They were eating pizza and laughing in the kitchen—“Ho-ho-ho, hee-hee-hee, ha-ha-ha.” In my ears they sounded just like the Beatles’ “I Am the Walrus.” I turned on the TV, and the movie The Pride and the Passion was on—Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, and Sophia Loren hauling a cannon across Europe and killing thousands of people. Not a good movie to watch on LSD. I was beginning to lose myself in a sea of darkness and doubt. It was almost like a box of firecrackers was going off in my brain, a lot of negative explosions—fear of what’s going to happen to me, fear of a world that is so sick and so negative and dark. I had all these thoughts and couldn’t come up with the words to describe what I was seeing. I don’t remember how I did it, but somehow at five in the morning I got the mechanics together to call Stan Marcum and ask him to come and get me.

Stan was the kind of friend who would say, “I’ll be right there” and mean it. He picked me up, and the first place he took me was to the woods in Fairfax, in North Bay. I was watching a beautiful golden sunrise, but what I was seeing was the world burning itself down. Suddenly I felt like I was Nero, fiddling away while a huge fire was happening all around me. I felt that the world was destroying itself and needed to be helped.

My mind was still higher than an astronaut’s butt, so Stan took me to his house, and he and Ron put me in a room to try to sleep it off. But I was wide-awake. Then they put on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The album was only a few weeks old then, and I heard “Within You Without You”—George Harrison playing sitar and singing about spiritual principles.

I needed that. Everything came together, and I finally started to come down. Stan asked me, “What happened this morning? What did you see?” I told him that I had seen the world on fire, crying for help. He asked, “What are you going to do about it?” I told him I had been thinking about that for a long time. This is what I said: “I want to help it heal.”

I felt like I actually gave birth to myself that day. I went from believing the world was coming to an end to figuring out what I had to do to stop that from happening. It had been a long, long night and day—I felt that the whole experience had given me power and brought me to my purpose in life.

Stan and Ron listened to me talk. They heard the conviction. “We’ll be your managers,” they said. “We’ll quit our jobs—no more bail bondsman, no more barber. We’re going to join you, man. We’re going to help you. We’ll dedicate all our energy and money to you and the band.” I was blown away—these two hippie dudes were ready to invest in my career. They became two more angels stepping up—coming in at just the right time. I think about it now, and it felt like they’d been waiting to hear me say what I said as much as I’d been wanting to say it.

Stan said one more thing. “You have to get rid of Danny and Gus—that’s the way it is, man. They’re not bad people, but they’re not committed. They’re weekend musicians; you’re not. We can tell that. We’ll drop everything for you, but you got to drop them.”

I was like, “Oh, damn.” I could tell that Stan and Ron had been thinking about this for a while. I knew they were right, but Danny and Gus were my oldest friends in San Francisco. Making us late at the Fillmore kind of sealed it, but if anybody was going to tell them, I would have to be the one.

Danny and Gus were upset—really upset—and they got pissed off at Stan. I told them it wasn’t about their playing. It was because they just weren’t ready to take the plunge. That LSD trip made me realize that our thing was done—they were my friends, I grew up with them, but it was not something that I needed to hang with. It would have been like wearing shoes that didn’t fit anymore.

We stayed in touch over the years, but they never stuck with music, at least not as a profession. They’re both in heaven now—they left way too early. Cancer got Gus, and diabetes got Danny—he lost a leg, and the last time I saw him I got the feeling his soul was broken because he had lost his parents and his two sisters, and he was the last one left.

I said good-bye to Danny and Gus, and I finally said good-bye to living with my mom and dad and moved in with Stan and Ron on Precita Avenue. That was the nest that nurtured the birth of the band. Their place was just ten blocks from my family’s house, but my parents wouldn’t know where I was for almost two years. They would look for me all over the city even though I was right next to them. But I didn’t want them to do the same thing they did in Tijuana. I left without even taking my clothes.

That really was the beginning of Santana right there.

Bands living together in San Francisco was normal back then—it helped focus the energy, and it saved money. The Grateful Dead and Big Brother had their houses. So did Sly. Some were in poor, funky neighborhoods, but that was okay if it helped you to afford it. This kind of thing still goes on in Paris now among African musicians—they’ll rent one apartment and cook and play music together. Same thing. You learn to trust each other.

When I moved in with Stan and Ron, I took over a small room. I borrowed clothes when I needed to and bought some stuff at Goodwill. We cooked together and closed the curtains and brought chicks in and out. People would come around, because Stan was a very social guy in a nice way, not a bullshitter. We’d smoke weed, take acid, and drink wine and discuss Miles and Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa. Whoever we were listening to. We listened to a whole lot of Bob Dylan. Stan and Ron had a lot of jazz in the house, too—that’s when I really got to hear more of Grant Green and Kenny Burrell as well as Wes Montgomery.

The three of us—Gregg, Carabello, and I—still went to the Fillmore, sneaking in under Bill Graham’s eyes. We’d stand in front of the stage, look at the bands, and say, “You better bring it, man. Let’s see what you got.” We heard the Young Rascals and Vanilla Fudge from New York, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Procol Harum from England. Certain bands didn’t disappoint us. Steppenwolf was mean—they had charisma. We opened for them a lot in Fresno and Bakersfield and Lake Tahoe.

Other bands were like copies of copies. A few of them had some corny one-song hits. We’d say, “Nah—this sounds like a bad rehearsal. Let’s go.”

Not B. B. King. I had been so excited to see him for the first time in February of 1967. Finally, the teacher I had started with and kept coming back to was coming to the Fillmore! The first time I had heard his music was in Tijuana at Javier’s house—all those LPs on the Kent and Crown labels.

B. B. was the headliner after Otis Rush and Steve Miller. Another great triple bill. I was there for the opening night. Steve was great, Otis was incredible, and then it was B. B.’s band onstage, vamping. (Later on, I learned what his close friends call him—just B.—but in my mind he will always be Mr. King.) Then B. walked onstage, and Bill Graham went up to the mike to introduce him: “Ladies and gentlemen, the chairman of the board—Mr. B. B. King!”

It was like it had all been planned to build up to this. Everything just stopped, and everyone stood up and applauded. For a long time. B. hadn’t even hit a note yet, and he was getting a standing ovation. Then he started crying.

He couldn’t hold it in. The light was hitting him in such a way that all I could see were big tears coming out of his eyes, shining on his black skin. He raised his hand to wipe his eyes, and I saw he was wearing a big ring on his finger that spelled out his name in diamonds. That’s what I remember most—diamonds and tears, sparkling together. I said to myself, “Man, that’s what I want. This is what it is to be adored if you do it right.”

Gregg, Carabello and I saw B. in concert when he came back in December of ’67, and I was able to study him almost in slo-mo, waiting for him to hit those long notes of his. I was thinking, “Okay, here it comes—he’s going to go for it. There it is. That note just freaked out everybody in the place, man.” People were in the hallelujah camp. I noticed that just before he would hit a long note, B. would scrunch up his face and body, and I knew he was going to a place inside himself, in his heart, where something moved him so deeply that it was not about the guitar or the string anymore. He got inside the note. And I thought, “How can I get to that place?”

Years later I was invited to the Apollo Theater to play in an event with, among others, Natalie Cole, Hank Jones—the great jazz pianist—Bill Cosby, and B. B. King. B. came up to me beforehand and said, “Santana, you going to play it tonight, man?” He rarely calls me Carlos.

I said, “I’m waiting for you to tell me, man.”

“Come on: we want to hear the blues.”

So I hit it. After I played, we walked out, and B. grabbed me. “Santana, I want to tell you, you don’t have a good sound—you have a grand sound.”

Shoot. I graduated right there. To be knighted by B. B. King himself? “Thank you, sir.” That’s all I could think to say. I don’t remember getting back to the hotel that night.

Bluesmen are not always so gracious. Buddy Guy can be a headhunter. If you’re playing with him and don’t come in the right way, he’s going to make sure he’s looking at you while he’s dissecting you. His attitude is, if you can’t keep up, get the hell off the stage.

Albert King wouldn’t even wait for you to start. Once at a blues festival in Michigan, Albert Collins went to meet Albert King and said, “I just wanted to meet you, shake your hand, and tell you how much I enjoy your music.”

King replied, “Yeah, I know who you are. I’m going to kick your little ass when you get onstage.”

I love these kinds of blues stories. To me they grab the essence of what the blues life is about—the attitude and the cockiness and the humor. Here’s another one: there was a blues revue in 2001 at the Concord Pavilion in Concord, California, with an incredible lineup. I had to be there. I got there just as Buddy Guy was arriving. “Hey, man, good to see you here!” he said to me.

“What’s going on, Buddy?”

He looked me up and down. “I hope you didn’t make the same mistake Eric Clapton made.”

“Oh, yeah? What mistake is that?”

“Coming over to see me without a guitar! But you know I always bring two.” He started laughing, with all his gold teeth shining.

Then he pulled out a flask. “Santana, I know you meditate and stuff, but I got to have my little shorty dog. I need to tune my guitar—why don’t you pour me some and help yourself to some, too?” So I did, and immediately he said, “Hey, whoa! You trying to get me drunk? You put more in mine than yours.”

“No problem, Buddy. I’ll take the bigger one, man.” He’s constantly testing me. I’ve gotten used to it.

That night he played an incredible set, connecting with people as he always does, walking out into the audience while he plays a solo, because he wants people to smell him, and he wants to smell them, too. He’ll do his big buildup thing, playing a solo and building the energy to the point where you know a big sustained note is coming. There’s a noise he makes with his mouth that you can hear—a grinding and churning, like it’s coming from all the way down in his gut—before he hits the guitar and the note comes up and hangs forever: loud and long and deep and soulful, and he’s got everyone in the crowd with him and he knows it. He grins with all those beautiful golden teeth, like he’s saying, “Shit—I willed this goddamn amplifier and this guitar to sustain like that. I can do it as long as I want.”

Then there’s the song that has the lyrics, “One leg in the east / One leg in the west / I’m right down the middle / Trying to do my best”! And the women start screaming. Every time I see Buddy, he’s creating a riot, you know?

He brought me out, and we jammed a little bit. He finished his set, and we were backstage, hugging and sweating, and I was just floating, man. Off to the side, we saw some people coming like it was high noon at the O.K. Corral: four big bodyguards, dressed up real sharp, two on the left, two on the right. Behind them was… who else? B. B. King himself, on the way to the stage—his band was already playing.

Buddy pushed me around a corner. “Carlos, stand here so B. won’t see you. When I call you, come on out, okay?” He had a twinkle in his eye.

“Sure, whatever you say.”

Buddy stepped in front of the whole procession, blocking the way. They got up real close, and B. said, “Hey, Buddy, what’s up?”

Buddy looked at him without a smile. “B., how long have you known me?”

He said, “A long time. Where you goin’ with this, man?”

Buddy took his time. “Well, there’re things about me you don’t know—like I have a son you didn’t know I had.” Then he called to me: “Come here, man,” and he put me right in front of B., holding my shoulders. B. was still focused on Buddy, wondering what he’s up to, and all of a sudden he sees me and starts laughing. “Buddy, you ain’t nothin’ but a dirty dog—come here, Santana!” He gave me a huge hug.

Buddy was right. I am his son, just as Buddy and I are B.’s sons.

B. grabbed our hands. “You’re both walking out with me. Come on!” We went onstage together, and B. raised our hands above our heads like we were prizefighters, and the crowd went, “Yay!” Then B. turned to us with a serious look. “Okay, you guys can get out of here.”

It was time for Daddy to go to work.

Back in San Francisco when I was living with Stan and Ron, every few weeks we’d put on classical music and clean the house with hot water and ammonia from top to bottom. It was easy for me to get used to that kind of group living because of how I grew up with my family, especially my mom. She encoded that in my DNA. And when you’re a hippie, man, everybody wants to share that joint. We shared food and weed and money and chores.

In our house, most days we woke up, ate breakfast, and went to work getting gigs and finding new musicians. Intention was focused on the band: time, energy, money. Sometimes Stan would bring musicians over—we would play with them until six in the morning. We were trying out new players, but we were also just jamming and being social.

We did a few gigs at street fairs and small clubs like the Ark in Sausalito with the bass player Steve LaRosa, who was really good and very attentive to what the drummer was doing. Drummers went in and out for a while. There was Rod Harper, who was good on certain kinds of songs but not on others. Then we found Doc Livingston, who came from somewhere in South Bay. He had certain mechanics—he could play double bass drums, but the thing I most liked about him was that when he played with mallets he could create a kind of vortex to play in. Real drummers don’t need to be told when to get some mallets out. But he didn’t know about just playing funky. That was too bad. I had a feeling he wasn’t going to last, because he was a real lone wolf. Every time we had a meeting Doc would be off somewhere else, looking at the floor.

One night we played in a jazz bar. It was called Grant & Green because that’s where it was. A bassist jammed with us on “Jingo”—he was tall with green eyes and dark skin and was really the most gorgeous-looking black man I’d ever seen.

David Brown was basically a silky person to be around—never angry, no strife. He loved Chuck Rainey’s bass playing. As Jimmy Garrison was with Coltrane, David was always way behind the beat, never in the middle. I knew it was on when I heard him—I don’t like bass players who play with too much precision. But I couldn’t look at David’s feet when we’d be playing a song because it would throw me off—he was that far back. Later, when Santana got its sound together, it all made sense—David laying back in the beat, Chepito Areas hitting it way up front—a balance of precision and conviction, you know?

He may have been behind the beat, but I’ve never seen anyone pick up women faster than David Brown. He was a chick whisperer. He would scratch his chin and go up to a woman real close and say something in her ear. He’d take her by the hand, and they’d walk off.

We asked David to join us that same night.

We started to look for another conga player, too. I’m not sure why we had to, but Carabello could be such a goofball sometimes, showing up late or not at all. He’s the only person I know who made a U-turn driving on the Golden Gate because he forgot his Afro comb. One time we were playing the Ark, and Carabello was using the kind of conga that has the skin nailed onto it, so the only way to get the right pitch is to warm the skin. He put the conga near a stove in the kitchen to heat it up and left it while he checked out a chick. He came back, and that thing looked like a pork rind—it had a big hole in it, and it smelled horrible.

I said, “You know what, man? You’re not getting paid.”

“Oh, man, that’s cold, man.”

“No, it’s not cold. You don’t play—you don’t get paid. You should have stayed here with the conga, man.”

Anyway, we had to drop Carabello for a while. Then Stan was down listening to the congueros at Aquatic Park when he met this cat named Marcus Malone. He was really good—self-taught, a self-made showman. He had no knowledge of clave or anything Cuban or Puerto Rican. But that wasn’t going to stop him. He had the idea for “Soul Sacrifice” and could make “Jingo” pop. I started hanging around with him more and more.

He was very, very sharp. Marcus “the Magnificent” Malone. Everything he wore was burgundy. He had a brand-new Eldorado: the upholstery and everything was a beautiful maroon. You can see it in the early photos—Marcus rocked a different style. We were street—he was slick. He was a player, and he was a street hustler. He’d step out from rehearsals and say, “I got to call my bitches”—and we would wait.

I was with Marcus the night that Martin Luther King Jr. got shot. We had a gig that night at Foothill College in Palo Alto, and he was driving. I started crying, and he said, “Man, what’s wrong with you? Why are you crying?” He was too tough, I think, to let his emotions show that way.

“Man, what’s wrong with you?” I replied. “Didn’t you hear they just shot Martin Luther King?”

He was like, “Oh”—and he just looked straight ahead.

Marcus was a tough dude, man. He had a lifestyle that was very different from ours. I don’t think we could ever get him to come over to our side of thinking—to let his girls go and trust the music to make it happen for him. He’d say, “No, man. You’re freaking hippies taking all that LSD and smoking pot and shit. I gotta deal with my bitches—they’re taking care of me.”

The band and I got tight with Marcus’s mom for a little while. She had a big garage and didn’t mind if we kept our instruments there and used it to rehearse. Years later I figured out that her place was very close to what is now the Saint John Coltrane Church. The one thing she asked was that we help her by painting her kitchen—so one day we all got to it and painted that kitchen. Of course I had no experience with that, but I don’t think we made too much of a mess of it.

It only took a few weeks—but by July of 1967 we had the foundation of Santana. I’m still amazed at how fast it came together. That’s how much talent was walking around San Francisco then. Also, it’s not like we said, “Let’s make this a group of people from different backgrounds—black, white, Mexican.” It’s just that we weren’t cut off from that opportunity. Among all the bands in San Francisco, we were closest in this way to what Sly did with the Family Stone. The city had all these cultures living close together, and when Stan, Ron, and I started to look for musicians, we opened a door and it didn’t matter who walked in—they fit if they had the music and the right personality.

It took a lot longer for our sound to develop. A few years later Bill Graham would say that we were like a street mutt: we had so many things mixed together we couldn’t know who we were. He said that as a compliment. We continued as the Santana Blues Band—sometimes just Santana Blues—but as our music started changing we didn’t know what style to call it. I already could see that the blues elevator was too crowded and that we needed to let that one go up and wait for the next one. Everybody was playing some style of blues—Paul Butterfield and John Mayall were laying it down. Cream and Jimi Hendrix were playing the blues, only louder. A year later, Led Zeppelin and Jeff Beck’s band would come in with their heavier sound.

In ’67 we had many new ideas and influences in the band. Everyone liked Jimi, the Doors, and Sly & the Family Stone. David was into Stax and Motown. Gregg brought his passion for the Beatles and was into Jimmy Smith and Jack McDuff. Doc Livingston also liked rock bands. Carabello was still hanging with us and still turning me on to Willie Bobo and Chico Hamilton. Marcus loved Latin music, blues, and jazz. He was the one who first turned me on to John Coltrane.

Not that I was ready for that yet. I was at Marcus’s place in Potrero Hill, near the projects and near where O. J. Simpson grew up. He left me in the back room while he went to check on his women. It was like an assignment: he left me with a joint and put on A Love Supreme. “Here, help yourself, man.”

The first thing I heard was Coltrane’s volume and intensity. It fit the times. The ’60s had a very loud, violent darkness that came from the war and riots and assassinations. Coltrane’s loudness and emotion reminded me of Hendrix, but it sounded like his horn was putting holes in the darkness—each time he blew, more light came through. The rest was kind of mysterious—I couldn’t make out the structure or the scales. I mean, I could play blues scales, but it just felt so alien to me. I remember looking at the album cover and seeing his face so calm and intense—it looked like his thoughts were screaming. It was one of the first times I realized the paradox of music: it can be violent and peaceful at the same time. I had to put it aside—it would take some time until I was able to understand Coltrane’s music and his message of crystallizing your intentions for the good of the planet.

California was a conservative place in general, but it seemed like anyone talking about politics at that time was from the left. People were supporting things like public performances and food banks and Cesar Chavez and the Black Panthers. Either you were against the war in Vietnam and against exploitation of workers and against anything that was racist or you were old and part of the problem.

It wasn’t just San Francisco. You could take LSD, turn on the news, and see people dying in Vietnam. They kept showing Buddhist monks pouring gasoline over themselves and burning to death to protest the war. How could your mind not expand? Later you saw the motel balcony where Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. Robert Kennedy lying on a kitchen floor, dying.

The ’60s were in your face, and there was no remote control to turn it off. That came later. When Santana did its first national tour in ’69, you could see the whole country was going in that direction—thinking and dressing differently, experimenting. Talking liberation. The thing is, this all happened in just two years. When Jimi Hendrix and Otis Redding and Ravi Shankar were playing the Monterey Pop festival in ’67, I was just getting started, happy to be opening for the Who at the Fillmore Auditorium. By ’69, I was playing Woodstock.

I was almost eighteen when the world started to ask questions that had not been asked before. Is there a better way than what we’ve been doing all these years? Why are we fighting here at home, and over there in Vietnam? Can we make this world a better place—can we infuse spiritual principles in everyday life? I had my own questions. What does that mean—tune in and drop out? What am I going to do? Where do I fit in all this?

San Francisco was the perfect time and place to experience the ’60s. The combination came at just the right time—a gift. I was a guitar player who had the conviction to make music his life. I was working with songs and vibrations when the sound of the electric guitar was what people were gravitating to. That instrument became another way to take people to new places, to make beautiful paintings. The electric guitar was the new storyteller. Suddenly, with musicians like Hendrix and Clapton and Jeff Beck, it was possible to go deeper into the guitar and transcend its actual construction. Something like the Fender Strat? As Jimi said, “You’ll never hear surf music again.” The electric guitar was able to transcend what it was supposed to do and communicate a state of grace on a molecular level.

It wasn’t just the way the instrument sounded: guitar solos were getting longer, too. The music all around us was starting to get longer. Even on the radio, songs were not just three minutes anymore—some FM stations would play a twenty-minute tune if a band put it out. Creedence Clearwater Revival was just getting started. They were already big in San Francisco and came out with a long version of “Suzie Q.” It was that “East-West” influence, and from the jazz world, too—Chico Hamilton, Gábor Szabó. Hendrix had “Third Stone from the Sun”—jamming with all the psychedelic studio stuff going on and talking about “majestic silver seas” and landing his “kinky machine.” If you played guitar, you couldn’t just make up something to go with a short section of a song and work it again and again. I had to open up to going on with an idea, having your own discussion. It wasn’t that difficult—I could talk. I had to just learn to listen. To hear the music and know when to go higher, when to jump, when to bring it back.

I would embellish a little even when I was playing violin, though my father discouraged that. He wanted me to stay true to the melody, put the feeling into that. This was different. I was opening up to thinking about energy and sound, not just notes and scales.

After leaving home and the Tic Tock, I had more time to listen and really dissect records—listen to them again and again, maybe twenty times. I’d listen alone with my guitar or with the other guys in the house. We would sit around and smoke weed and get fuzzy and hazy. Some music sounded like it was made for that. John Lee Hooker, the Doors, Jimi Hendrix—all weed music. Definitely Lee Morgan. I used to love to smoke to First Light by Freddie Hubbard. If it was Bob Dylan or Miles Davis, you’d get twice as high. When I started really listening to Coltrane, I’d get high, but after a while his music sets you straight, like he had some kind of regulator tone that doesn’t allow for fuzzy and hazy.

I remember talking with a lady who used to live in Mill Valley. She told me, “I heard you play, and I brought you some records.” One of them was by the Gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt. She told me he learned to play even though two of his fingers were stuck together. As soon as she left, I started listening—“Minor Swing” with both guitar and violin! Hearing Django go off on a solo gave me a whole new idea of what to do.

One night the Santana Blues Band was opening for James Cotton. Sometime in ’67, we had begun playing regularly at an old movie house in the Haight that some hippies fixed up and called the Straight Theater. The place was a little raggedy, but it felt right for us. We played Albert King’s “As the Years Go Passing By”—“There is nothing I can do / If you leave me here to cry…” My turn to solo came, and suddenly it was like opening a faucet. The water just flowed out. It was the most natural feeling. I wasn’t repeating riffs. I wasn’t repeating anything. It felt like I had turned a corner.

A writer once asked me what I think about when I’m soloing—this was in the early ’90s, when all three of my children were just kids. I told him I thought about combing my daughters’ hair before they went to bed, how careful I had to be so I didn’t make them cry. Playing a good solo is about being sensitive and not rushing, letting the music tell you what and when and how fast. It’s about learning to respect yourself by respecting the music and honoring the song.

Another time, my mom approached me and said, “Mijo, can I ask you something? Where do you go when you’re playing your guitar and you look up? All you guys look up. What’s up there?” I love my mom for having that childlike curiosity and just coming out with that question. I know she’s not alone. People want to know. “What’s it like in there? What’s it feel like?”

It’s difficult to explain—Wayne Shorter calls it the invisible realm. I call it a state of grace, a moment of timelessness. Playing a guitar and getting inside a groove and finding the notes is like the power that lovers have—they can bend time, suspend it. A moment seems like infinity, and then all of a sudden time meets you around the corner. I began to feel that when I was playing in Mexico—not a lot, but sometimes.

I don’t know if my solo on “As the Years” was recorded, but the band was starting to record ourselves in concert, asking the sound guys to do that so we could listen to our performances, study them. At first it was pretty painful—it always sounded different from the way I’d remembered it onstage, and everything sounded rushed. I’d go home and listen to it by myself, never with anyone else. In fact I still do that—I won’t listen to recordings of Santana in concert if there are people around me unless we’re working on a live album or I want to show somebody something we need to fix.

We also learned to play high. Gregg usually stuck to his beer, and the rest of us would smoke weed when we played—and we tripped a lot. Without a doubt, hallucinogens had a lot to do with the Santana sound. That’s the way it was with many groups then—there wouldn’t be the Jimi Hendrix Experience without them or the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper. There would only have been electric blues and “In the Midnight Hour.” Even the Beach Boys moved on from surf music because of LSD.

LSD was legal until sometime in late ’68. I also took mescaline and peyote—ground ayahuasca buttons—which was a really nice trip except for when you had to go to the bathroom. It wasn’t as electric as LSD, which could be a little intense because we cut it with speed.

Then we’d play.

Hallucinating is another word for seeing beyond what your brain is programmed to see. That’s what those drugs did for me with music—they made me more receptive to ideas and heightened my sensitivity. Normally your brain is on a leash, with built-in filters. When I tripped and played, those filters went away, and the leash was off. I could hear things in a new way. Everything became more watery—thoughts were more fluid, and the music was more flowing. I would drop, and the music didn’t sound so fragmented. It sounded like beads on a string that would go on and on.

That was the deal: it took courage to surrender and trust that when you had those hallucinations you were not in total control—and if you got afraid and tried to get that control back, you were going to have a bad trip. I always did surrender—I knew that it was going to get intense for a while but that in twelve hours or however long it took to finally pee it out, everything was going to be cool again. You learn that you can have fear or trust, but you can’t have both.

We started to really hear each other, get to know one another’s musical signatures. We were a collective, and everyone found a role—everyone had a chance to be lead sometimes. In rehearsals, Gregg was the stable one—he had his six-pack to drink, but he wouldn’t do anything else. He was the rock in the band when all of us were doing stuff, going to extremes. The rest of us could go out with the music or go a little crazy and depend on Gregg to be the stabilizer, holding the beat together with his left hand. Somebody had to be the string on the kite.

From the end of ’67 through the summer of ’68, the Straight Theater gave us Friday-through-Sunday runs and put us on bills with Charlie Musselwhite and various local bands, including one called Mad River. Once we played after a Fellini movie. We started noticing people coming back to hear us, especially women—some we knew from high school and others who were new to us. They started to bring their friends, and we started to get our own crowd.

We did a few shows at the Avalon Ballroom and a few benefits at universities. We got better in front of an audience, and people started to hear about the Santana Blues Band. Then we got our first review. It was Sunday in Sausalito, and we were playing outside for spare change. Someone came up to us and said, “You’re Santana, right?”

“Yes, that’s us.”

“You know you guys are in the Sunday pink section.” That was the entertainment section of the San Francisco Chronicle. Ralph J. Gleason—the newspaper’s top music writer, who also helped start Rolling Stone magazine—had named the top new bands coming out of the city. There were around twelve, including the Sons of Champlin, and we were the first he mentioned, saying that we had the X factor of excitement. I had no idea what that meant. I asked Carabello: “Hey, man, I’m still learning English. Qué es ‘X factor’?” He laughed. “Man, fuck. I don’t know, either. But who cares? We got it.”

I like the fact that even one of the best music writers in the country didn’t know what to call what we had, but he found a way to write about it. It was like the question of where Miles was going with his music by 1969—you couldn’t call it jazz. Miles wasn’t just jazz, and we weren’t just rock. We were listening to jazz records and African and Latin music—which is really all from the same African root—learning things, getting inspired.

At the Fillmore shows, I started to hear how loose the time feel could be when I heard certain drummers—like Jack DeJohnette with Charles Lloyd or Terry Clarke with John Handy. I couldn’t believe the elasticity. I started hearing words about making time more liquid, not so wooden. I heard how drums could be played very fast and light, the way some drummers could roll, and wow—everything hit just right. It wasn’t like some bands—clang, clang, like a cable car. I got to hear that jazz drumming on records: John Handy had a great live album from the Monterey Jazz Festival with “Spanish Lady” on it. I would listen to a percussion solo on Bola Sete at the Monterey Jazz Festival that showed me how you can add colors with cymbals and textures with percussion.

I think the most effective thing we were doing was mixing blues with African rhythms—and women really love that because it gives them another way into the music. Most men like the blues, and if you just play blues, like a shuffle, women will move a certain way. You’ll get through to guys and a few women. But when you start adding a more syncopated thing—also some congas—it’s a different feel, and people start opening up in another way. Now women can dance to it. They start swaying like flowers in the wind and sun after it’s been cloudy for a whole month. Something happens with that mix.

There’s another name for this mix—Latin music. All those African beats come through the clave rhythms that became part of the Santana DNA. That’s really what you’re hearing when you listen to Mongo Santamaría and Tito Puente and Santana. It’s Africa.

If you said “Latin” to me at that time, I would think about what I saw on TV—Desi Arnaz and “Babalu” and guys in puffy sleeves shaking maracas—and I knew I didn’t want to go there. To me, Latin music was very, very corny. The music that I did like before I really knew it was called música tropical or música del Caribe long before it was called salsa or boogaloo. I discovered Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri the same way I discovered Babatunde Olatunji and Gábor Szabó—from just listening.

Latin music was everywhere in San Francisco—it was on the radio and jukeboxes, and later on, when I was hanging with Stan and Ron, I was getting it in the clubs. I knew that Ray Barretto had a humongous hit with “El Watusi,” but I didn’t know he had his own band until I started going to the Matador. That’s where I heard Mongo Santamaría with his band. I had never really thought about these percussion guys having their own groups, as Chico Hamilton did. I was learning. Then I heard the percussionist Big Black—Daniel Ray—who had his own thing happening in San Francisco, more jazzy. I used to go see him at the Both/And, where Miles Davis used to play, too.

Everybody was listening to Latin music—my family, too. Irma and Maria still tell me that they used to have parties at our home on 14th Street because my mom wouldn’t let the girls go out. They would invite friends over, and they wore out the rug dancing to albums by Barretto and later El Gran Combo. Maria tells me that the folks who ran the grocery store downstairs would get angry because bottles would fall off their shelves from all the dancing. And poor Jorge—it was like what my sisters did with their Elvis Presley records ten years before. He says he’d go crazy hearing them play the hell out of “Bang Bang” by Joe Cuba.

Even if Santana didn’t have anyone from the Caribbean in the group at the beginning, we came to Latin music naturally. It was the congas—hearing those jams in Aquatic Park and liking them, deciding that we would have some in the band and that they were going to be part of the soup. Then it was, “What music makes sense with congas”? Well, “Jingo.” Then we started to hear music that could work with what we had, blues and congas, like “Afro Blue.” Then it was: “We’re going to write songs around the congas.”

The next thing I knew I was hearing more music with congas, and I started buying Latin records with the same passion I had for the blues. By this time Gregg and Carabello and I were living together in a house on Mullen Avenue in Bernal Heights, near the Mission, and it was like we were all in a study group: “Check out the congas on this Jack McDuff record! Have you heard Ray Barretto on Wes Montgomery’s ‘Tequila’ or on Kenny Burrell’s ‘Midnight Blue’? We gotta go hear him when he comes to town.” Then Carabello heard Chepito playing timbales, and Chepito knew more about clave than any of us and helped us cement the full Santana sound.

We were from the streets of the Mission District, and in the beginning we were sensitive about what the “clave police” were saying. We didn’t want to be intimidated by anyone thinking that we were trying something we didn’t know how to do. When they first came after us, I wish I knew then what I know now—that the feel of the clave was already in blues and in rock. The electric blues guys—Otis Rush, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Magic Sam—they all had songs with that Cuban feel. B. B. King had it—check out “Woke Up This Morning.” Bo Diddley put tremolo on his guitar and maracas in his music and created his own electric primitive clave, and guess what? That shit went viral.

Here’s another thing most people don’t know about rock and clave: Chano Pozo, the Cuban conga player with Dizzy Gillespie’s band, cowrote “Manteca.” You can hear the influence from that song in Bobby Parker’s “Watch Your Step” from ’61. Parker was a blues guy from Washington, DC, who passed away in 2013, and who knows how he got to “Manteca,” but it’s the same pattern. When I was starting, every guitar player had to know “Watch Your Step”—including George Harrison, who played around with it for the introduction to the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine.” Later Duane Allman used that feel on “One Way Out.” People need to know that. It all started with one Cuban song.

In 1968, Marcus really helped us show off this side of Santana—from “Jingo” to Willie Bobo’s “Fried Neckbones and Some Home Fries.” The chords from that one were a big part of our sound. Marcus had riffs that were his alone, and one time he came up with an idea—“Man, I wrote this song; I want you guys to help me out”—and started humming and slapping his knees. Then we each did a thing on it—I did a guitar solo that borrowed a lick that Gábor Szabó played on a Chico Hamilton track. Later we called it “Soul Sacrifice.”

We were young—I didn’t appreciate at the time how good Gregg was for us. He’s a great soloist. I can remember watching his posture, and how he’d get into it so deeply, watching the veins appear in his throat, all that tension and conviction. He’s a great arranger, too, which connects to his solo style.

Speaking of arrangers, in 1970 Santana did a Bell Telephone Hour show on TV. I’ll never forget it: Ray Charles was on the same show, so we got to see him do “Georgia.” I remember they were running through it, and suddenly Ray shouts, “Stop! Stop the band! Hey, you—viola in the third row. Tune up!” I wasn’t sure if we should stay quiet or applaud.

Anyway, they wanted us to do “Soul Sacrifice” with the string section, and the whole arrangement was based on Gregg’s solo. That’s how lyrical a player he is. He also has a really, really powerful sense of knowing how to start a story—check out the opening of “Hope You’re Feeling Better” or “Black Magic Woman.” Santana likes dramatic openings, whether big or mysterious.

We started playing “Black Magic Woman” at this time, just after it came out. It was a song by Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac that was a blues-rumba of the kind that Chicago blues guys would sometimes play. It was really Otis Rush’s “All Your Love (I Miss Loving)” with different words. We brought up the Latin feel in Peter Green’s version, and when we played it live it made a great segue to Gábor Szabó’s “Gypsy Queen.”

One of the ways we stuck out from the rest of the bands in San Francisco was that we weren’t really psychedelic or purely blues. We also didn’t have horns, as Sly & the Family Stone did—we didn’t have that funk rhythm, either. That summer Sly became a local hero. His “Dance to the Music” was everywhere, and those different voices really gave it a family vibe. Soon you could hear that Sly “sound fingerprint” all over the radio. Sly changed Motown—the producer Norman Whitfield started doing the Sly thing with the Temptations. Sly even changed Miles Davis. Miles would tell me later about watching Sly & the Family Stone just tear it up at the Newport Jazz Festival. That had to have hit Miles hard, to get him to change his music.

Let’s face it—Sly Stone at his peak changed everything. The only person he did not have to change was James Brown, because James was already there. Sly had to get his funk from somebody, and he got his soul straight from the church. Sly’s father was a minister and a preacher, and Sly was, too—just a more multidimensional one. He was the first guy who had female and male musicians, black and white. We were so proud that a cat from Daly City could go and change the world like that. We still are—in San Francisco, he’s still our Sly, man.

It was around this time that I first met Sly. Carabello used to hang out with the Family Stone in Daly City. He brought me over. “Hey, man, we got invited to go to Sly Stone’s house. He wants us to open up for him on a couple of gigs, and he wants to produce us.”

“Really? Okay. Let’s go.” When we got there, Sly said the wrong thing from the start—with attitude: “So you guys play that blues Willie Bobo stuff, huh?” I’m thinking, “What ‘blues Willie Bobo stuff’? I’m not going to let this guy encapsulate me and define our music that way.” He’s a genius, man, no doubt about it, and he was already on the radio and everywhere else and he had the baddest bass player in the world—Larry Graham. But I didn’t like somebody looking down at me like that.

“I’m fuckin’ out of here, man.”

Sly wasn’t wrong; it was just how he expressed himself. Santana was starting to get it together with a Latin rock reputation. It was a way people could label our sound. Just don’t call us blues Willie Bobo stuff.

That wasn’t the end of that, though. The worst name I think I heard used to describe Santana was in Rolling Stone’s review of our first album—“psychedelic mariachi.” Why? Just because I’m Mexican? What an ignorant, touristy thing to write.

I remember even my Caucasian friends telling me how stupid that was. I don’t like to be reduced to anything other than a person who has a big heart and big eyes for a big slice of life. I’m not necessarily against music writers, but sometimes they don’t think before they write. And when they do get it right? I remember that, too—like the jazz writer who described Albert Ayler’s music as a Salvation Army band on acid. I read that and heard what he meant—and I love Albert Ayler. I thought, “Damn, that’s a real badge of honor.”

Here’s what I think—if you’re describing music that’s original and not clichéd, don’t use clichés to describe it. Be original and be accurate. We were open to Latin influences, and I think when we did it we did it well. Well enough to get back to playing the Fillmore.

I hadn’t known that Bill Graham used to go hear Latin big bands in New York City. It was only later that he told me that he used to hang out at dance clubs in Manhattan and that he could mambo and cha-cha. It was in his blood. He knew about congas and Latin rhythms, and he liked them.

In the spring of ’68 Bill was holding open auditions at the Fillmore Auditorium on Tuesday nights. Despite being unofficially blacklisted, we were welcome to play those, and we did. He didn’t attend every time, but he heard us on a few occasions, and he heard how our music was changing. His ears were working. Speaking of Willie Bobo, Bill was the one who said we should do “Evil Ways” for our first album.

We didn’t know it then, but around this time the Fillmore Auditorium became too small for the crowds. Bill took a plane to Sweden to meet face-to-face with the owner of the Carousel Ballroom, which was on Van Ness Avenue not far from the Mission. But the guy lived in Gothenburg! Bill flew out and met with him. They ate and drank and talked about a contract, then Bill flew back. That’s how he started the Fillmore West. I don’t think anyone else back then was serious enough to do something like that. If Bill believed in something or someone, he’d go after it. I admire that.

Bill would need bands to play this new, larger venue, and he knew we were getting a really good reputation with our shows. In June we played a benefit for the Matrix at the Fillmore Auditorium—the first time we had played there in a year. Stan and Bill talked, and Stan told him we had a new lineup with new songs. We wanted to play the Fillmore West, and we’d never be late.

He also told him the band had a new name—just one word, and it wasn’t blues.