CHAPTER 9

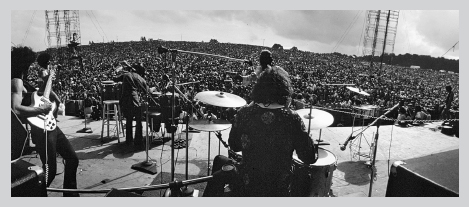

Santana at the Woodstock Music & Art Fair, Bethel, New York, August 16, 1969.

In 2013, when President Obama welcomed me as a Kennedy Center honoree along with Herbie Hancock, Billy Joel, Shirley MacLaine, and Martina Arroyo, what was the first thing he said when my turn came? Something about my being twenty-two and playing in an altered state of mind at Woodstock—not the usual stuff people talk about at the White House. Everyone laughed, and so did I. Obama’s not alone—to most people that’s the Santana moment. People still see it in the movie about Woodstock—Santana playing “Soul Sacrifice”—and writers still ask about it. Yes, I was tripping, and yes, the guitar felt like a snake in my hands. No, I still can’t remember much about it, but I’ll tell you everything I do remember and what I think about it today.

I’ll also tell you this: having the president talk about you is a true opportunity to accept with nobility and humility the greatness of your own life. At the same time, it’s a rare moment when you can see that, with humility, you must accept that you do not control your own life—that you are not separate but connected to a bigger whole. At Woodstock, I think Santana played a great show, but I do not think Santana was responsible for all that happened afterward. That’s like a cork floating on top of a wave in the middle of the sea, bobbing up and down and telling itself it’s controlling the entire ocean—that’s an ego out of control.

There were a lot of things that nobody planned at Woodstock but that made it work for us. If we hadn’t stayed in the town of Woodstock for the week before the festival, we probably would have gotten stuck in traffic and showed up late or not made it at all. And if some groups hadn’t been late getting up there, we wouldn’t have gone on early in the day and we could have gotten caught in the rain later that day and had our show messed up or even been electrocuted or forced to quit. And if any of that happened, maybe “Soul Sacrifice” would not have made it into the Woodstock movie and nobody would have seen us.

There were a lot of angels stepping in and making a way for us—the more time goes by, the more I can say that with clarity and confidence. I’ll say it again: the one angel who deserves the most credit is Bill Graham. He got us the gig when nobody had heard of us. We had just finished our first album, but it hadn’t been released. When Michael Lang, who was producing the festival, asked Bill for his help, Bill told him, “Okay, this is a big endeavor. I’ll help you with my connections and my people. They know how to do this. But you need to do something for me—you need to let Santana play.”

“Okay, but what’s Santana?”

“You’ll see.”

Most people cannot think of Santana without thinking of Woodstock at the same time. I don’t mind being linked to it—in fact I’m really, really grateful. But people need to know that Woodstock had everything stacked up against it—and that against all odds three days of peace and love and music prevailed.

Bill called a meeting for everyone in the band. It was sometime in July of 1969. He was living in Mill Valley then, the white side of the Bay Area, where the hoity-toity rich people were. We all went over, looking at the houses—he had put together a nice outdoor buffet for us. We were all impressed. Then he sat down and told us why we were there. Usually he was always hurrying, but he took his time—he had a lot to say.

“Some groups are not doing so well right now—Hendrix is not selling; Jim Morrison’s in trouble for exposing himself. I hear that Sly is doing too much coke.” He gave us the full picture of what was happening in rock right then.

“I’m sending you guys to the East Coast, and when you come back everything will be different. First you’ll go to Atlantic City and New York City, then Boston and Philadelphia, and finally a big festival in Texas—you’ll play there with Sam and Dave, Led Zeppelin, and B. B. King. You’ll go from playing small halls that hold fifteen hundred to two thousand people to festivals where there are fifteen thousand to thirty thousand people, then a huge festival in upstate New York where there will be maybe eighty or ninety thousand people. You’ll do great.

“The festival in Woodstock is going to change everything for Santana. After that, people are going to recognize you everywhere, and it will totally fuck up your head. You’re going to think you’ve always been famous. People are going to treat you like you’re a god. The next thing you know you’re going to need a shoehorn to walk into a room because your head’s going to be so big.” Bill was being direct. “Keep your feet on the ground—don’t get swept up by all that.”

We were like, “Oh, man, don’t bring us down with that hippie shit. We’re from the ghetto, we’re real. We don’t think like that.”

Bill got serious. “Believe me: as true is true, it will happen.”

Our first album was about to come out, and before we left California Columbia Records had one of their annual conventions in Los Angeles, and we went down there and played a special show for all the sales and marketing people and publicists and bigwigs like Clive Davis. I didn’t get to meet Clive that time, or at least I don’t remember meeting him then.

The point of the show was to get the record company people all excited about the label’s bands and their new records—to get them to give us an extra push. It was there where we decided on an obvious name for the album—Santana. I always felt like a cat in a dog pound at those so-called industry events because of the way certain people would wear their suits and walk and “Hey, baby” you. People who’d take all the credit and the money from your music and tell you that without them you wouldn’t be who you are. Clive was an exception to that rule, I later found out.

The night after we played the convention we were in New York City, playing the Fillmore East, the hall that Bill opened the year before so he could bring the San Francisco magic to the East Coast. We were back at the bottom of the bill—in fact we weren’t even on the marquee, because it could only accommodate so many names and we were opening for Three Dog Night, Canned Heat, and Sha Na Na. That’s a lot of letters. I remember Bill telling me that once he booked Rahsaan Roland Kirk there, and Rahsaan insisted that his name be on the marquee, so Bill built an extra wooden sign to hang from the bottom to accommodate him—and Rahsaan was blind!

We could feel immediately how different the crowds were from those in California—a different kind of energy, a little intimidating. New York City people don’t come to you; you have to go to them. They’re very astute, like sharks. They can tell if you’re feeling out of place—they can smell fear. That first time we weren’t anything but polite: “It’s nice to be here, and we hope you like our music.” Then we just played.

The other bands were looking at us like, “What is this kind of music?” and we were looking at them the same way. Three Dog Night had a smooth rock sound from Los Angeles with very radio-friendly songs. Sha Na Na was a kind of parody act of ’50s doo-wop—they might as well have been a Broadway show. Canned Heat was closest to what we were doing, and you could hear they had that John Lee Hooker boogie in their music, and that was okay with me.

It was helpful to be in that kind of show so we could learn not to be afraid of competition or new audiences. Back then we were constantly monitoring ourselves to see how we fit into the music of the time—what do we like? And, just as important, what do we want to stay away from? Everybody in our band was really vigilant about not letting the band be talked into something we didn’t want to be. It was fun playing with that kind of freshness—audiences still not knowing who we were, opening up for everybody, then grabbing the audience and pulling them our way. I really dug the reaction of the people to our sound back then.

Even though Bill had called it, we didn’t really know that our first trip east was going to be our last chance to be that anonymous—that after the next few weeks we would never again be the new and unknown band coming into town. That was going to change forever, thanks to Bill, who really, really nurtured us meticulously. With that first tour he prepared us psychologically and physically for all that was going to happen.

Santana stayed in New York City for a while, playing a few shows after the Fillmore East gigs—a festival in Atlantic City, the World’s Fair in Queens, and a gig in Central Park. We got to know the city on that first visit—we stayed in some hotel on 5th Avenue and walked around a lot. Bill turned us on to Ratner’s, a kosher restaurant next to the Fillmore East. We took a cab up to Harlem and saw the Apollo Theater. It was August, and if you know New York City, it has its own smells in that heat, and you especially notice it if you’re coming from California. It’s different: the pizza joints and the sandwich shops and the garbage and the sewers—everything. It’s all mixed up together.

It was amazing how fast things moved in New York. I remember walking down the street and seeing a taxicab that had been in an accident and was upside down. You could feel that energy pulsating with a kind of audacity and insanity. I would be telling myself, “You don’t scare me. I’ve walked your streets and now I’m one of you and I smell like it.” Once you claim New York you draw energy from it—it doesn’t drain you and it doesn’t scare you. The next time Santana came through was in November, and it was already feeling like home.

Then we played a college up in the Catskills and ended up in the town of Woodstock. Bill had rented a house for us, and that’s where we stayed almost a whole week before the festival. There wasn’t that much to do—so we all found people to hang out with. I remember Chepito complaining—he was sharing a room with David, who was meeting chicks and bringing them back to the house. “I’m like a mouse smelling the cheese,” Chepito said. “But he’s not sharing.”

There were other people hanging around up there—Bob Dylan lived near there, and Jimi Hendrix had rented a house, too, but I never saw any of them. I was really shy about hanging out because those kinds of guys didn’t know me then. It made me feel like a fly in the soup, and I didn’t want to be a groupie for anybody—I don’t want to show up unless I’m invited personally. So I said, “No, I don’t think I want to go and just hang.”

We saw Bill around once a day, but he was mostly on the phone, and we could tell there was a buzz going around about the festival. It was going to be big—really big. Some people were getting scared—people who lived around there—because many of the hippies who were coming got there early and started camping out. I remember a rumor that Governor Rockefeller was thinking of sending the National Guard in to make sure it was safe or even shutting down the festival altogether. The newspapers started talking about it like it was a disaster waiting to happen. It wasn’t a disaster for us. The disaster would have been if Rockefeller had taken over and turned it into a fire drill with the police regimenting it.

Then Friday came, and we heard it was an incredible mess—people stuck in traffic on the highway, abandoning their cars, technical problems with the sound. There was no way we could go and see for ourselves. We were scheduled to play the next day and were told we’d have to be ready early to be sure we could get there on time. So we got up at five on Saturday morning, waited, and finally piled into some vans and drove to a place where there were green helicopters that looked like the kind the army used in Vietnam—they were flying people in and out. Next thing we knew we lifted off, and a few minutes later we were swooping over a field, looking down in the morning light at a carpet made of people—flesh and hair and teeth—stretched out across the hills. That’s when it dawned on me how big this whole thing really was. Even with the noise of the helicopter we could feel the people when they started cheering after somebody had finished a song or had said something they liked—a huge roar came up from below.

I remember turning to Gregg and saying, as a joke, “Nice crowd!” I also remember thinking about something my dad taught me—if you’re a real musician, it really doesn’t matter where you are or the number of people in front of you. You could be playing Woodstock or Caesars Palace or an alley in Tijuana or at home. When you play, play from the heart, and take everybody with you.

My father’s relationship with music was on a purer level than mine is. Yes, there was the money side—he did it to provide for us, but he wasn’t distracted by volume. Volume is when you collect a royalty check that’s so big you think somebody made a mistake. My father made a certain amount, and that’s what he knew. He never heard of Carnegie Hall, so he did not factor that into the equation. Any place where he could play and where people were receptive, that was fine with him.

Woodstock was all about volume. First we were above all those people, then we landed and were in it. Right away you could smell what New York State smells like in the summer—very humid and funky, plus five hundred thousand sweaty bodies and all that pot. They dropped us off behind a big wooden stage that looked like workers had just finished building it that day—and from the look of things they still had more to do. They showed us where to put our stuff and where to wait, and I started looking around for someone I knew, and I saw Jerry Garcia having a good time and laughing. He came up to me and said, “So what do you think of this? We’ve been here a long time already—what time are you supposed to go on?” I had been told that we’d be going on three bands after the Dead, so that’s what I told Jerry. He said, “Man, we’re not going on until later tonight.” That meant we were going to be there all day and into the night. So I thought, “I might as well get comfortable.” It was just after noon, and the first band of the day was on.

Then Jerry held his hand out. “Do you want it?”

“Want what—what you got?” It was mescaline. That’s how casual it was in those days—I took it right away. I was thinking, “I’ll have time to enjoy this, come back down, drink a lot of water, get past the amoeba state, and be ready to play by tonight. No problem.” Right.

Things were definitely more messed up at Woodstock than we had thought. Because of all the traffic a lot of bands were having trouble getting to the festival, so the organizers had to ask the bands that were there to play or there would be big gaps in the flow of music. Of course I didn’t know this then. I remember hearing Country Joe and the Fish onstage when things were just starting to get elastic and stretch out. Then suddenly someone came up to us to tell us that if we wanted to play, we had to get on stage now. It wasn’t Bill—I didn’t even see him around. We didn’t argue—we just grabbed our instruments and headed to the stage.

It was definitely the wrong time for me. I was just taking the first steps on the first stage of that psychedelic journey, when things start to melt when you look at them. I had played high and tripping before, so I had the confidence to go for it and put on the guitar and plug it in, but I remember thinking this was not going to be representative of what I can do. When a trip starts happening, all of a sudden you’re traveling at warp speed, and the tiniest things become cosmically huge. The opposite happens, too, so everything is suddenly the same size. It’s like that scene in Kubrick’s movie 2001 when the astronaut is traveling beyond Jupiter with all the lights whizzing by—it felt like I was almost at the stage of giving birth to myself again, and we were just starting the set.

When we got onstage we saw that they had set us up really close to each other, which was great because that’s what they normally did back home, and the roadie guys had come through. I think that was the best thing that happened to us that day: we could really see and feel each other and not get lost. Then someone announced us, and we could see the huge crowd in front of us—our album was just about to come out the following week, and “Jingo” wasn’t being played yet on the radio, so unless people in the audience were from the Bay Area or worked for Columbia Records, there was no way they had heard about us. It’s one thing to play to a crowd that big, and it’s another thing to be totally unknown doing that. But I had other things to think about.

The rest of the show is a blur—really a blur. We started with “Waiting,” the first tune from our album, and that was like our sound check. I was tripping, and I remember saying inwardly, “God—all I ask is that you keep me in time and in tune.” I kept myself locked on the usual things that helped me stay tight with the band—bass, hi-hat, snare drum, and bass drum. I was telling myself, “Don’t think about the guitar. Just watch it.” It turned into an electric snake, twisting and turning, which meant the strings would go loose if it didn’t stay straight. I kept willing the snake not to move and praying that it stayed in tune.

Later I saw myself in photos and in the Woodstock movie. All those faces I was making while I was playing reminded me that I was trying to get that snake to hold still. Then I saw the guitar I was playing—a red Gibson SG with P-90 pickups—and it all made sense. I always had trouble keeping that guitar in tune, and even though I needed a new one, the band had voted collectively not to spend the money. That’s how Santana still was then—a collective. It was that way until at least the middle of 1971. Not long after the festival I got so frustrated with that guitar in a rehearsal that I ended up throwing it against a wall and breaking it, which forced the band to get me a new one.

We only played forty-five minutes at Woodstock, but it felt twice as long. Each note I played felt like it started as a blood cell moving inside a vein and pumping through my body. I had the sense of everything slowing down—I could feel the music coming up inside me and out through my fingers—I could watch myself pick a note on the guitar and feel the vibration go into the pickup, through the wiring inside the guitar, down the guitar cord to the amplifier, out the amp speaker into the microphone, through the cable into the big speakers on the side of the stage, out into the crowd, and all the way up the hill, until it bounced and we could hear the echo coming back to the stage.

Later I thought about the tunes we played at Woodstock, and I realized I had forgotten everything about the first half of our set. I did remember the last few songs, including “Jingo” and “Persuasion,” and I remembered that we did “Fried Neckbones” as an encore. And of course “Soul Sacrifice,” which ended up in the movie. I remember hearing the crowd yelling and clapping, then I remember going off the stage and turning back to see Gregg behind me. He had a look of victory on his face, like, “Yeah! We did it.” Then Bill Graham caught his eye and gestured him to turn back around, like he was saying, “Not so fast—look at the crowd. Savor this moment.” Gregg turned around, and his face was like a little kid’s—just amazed. I turned and did the same thing. I think Bill was probably more proud of us than we were, because we were all just a little shell-shocked.

It’s funny when I think about it. With everything else that was happening then, all the people and noise and getting hustled on and off, my last thought before leaving the stage was, “I’ll never trip again—not for a gig this important!”

For me the best thing about being connected to Woodstock is that most of us are still around to talk about it—Gregg, Carabello, Shrieve, Chepito, and I. We’re alive and vibrant. Most of all, we still stand for the same things that Woodstock represented—consciousness revolution coated with peace and love and music. The audience was filled with people who had a deep, emotional investment in making change happen. It wasn’t just people wanting to smoke a joint and get laid—although many did both—and it wasn’t about wanting to sell T-shirts or plastic flowers.

The original Woodstock wasn’t about selling anything. It wasn’t regimented or organized enough for that to happen. In fact that’s the beauty of it, and that’s why people are still talking about it. It came together naturally and was about using music and peace to show the system that there were a lot of freaks out there who wanted their voices heard. They wanted the freedom to be who they were, and they wanted the war to stop: “Hell, no, we won’t go.” We were saying that the war wasn’t over there, in Vietnam. It was right here at home, between the government and the hippies at Woodstock—between the system and the people who have no voice. In ’69, we had a generation with an agenda, and the groups that played Woodstock helped get that agenda out into the world and gave the people a voice.

The one problem back then was that there was no middle ground—that was not good, either. Some people were saying if you weren’t supporting everything America was doing, you were not being patriotic. Meanwhile a lot of hippies were making rules of their own and talking about the servicemen who were coming back home injured or without legs—calling them baby killers. Now it seems that we are back to that same thing—people judging people and making decisions without knowing enough—and there’s still no middle ground.

The true hippies thought for themselves and helped bring about a change that we needed in America. There are not enough hippies right now, in my estimation. And besides, I don’t care who you are—part of the system or a hippie—you have to learn to think differently from the crowd. Think for yourself and work for a better world. Don’t do anything with violence, but do make an extreme change to your own mentality. Question authority if it’s not divinely enlightened. Thomas Jefferson said it his own way—rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God. In that sense, both Jesus and Jefferson were downright hippies.

That’s the real lesson of Woodstock. The first Woodstock came and went, and two other Woodstocks have happened since 1969, but there’s only one of them that stays in our minds, and that’s because of the peace, love, and joy. I remember when I was asked to play the twenty-fifth anniversary—I was touring Australia. I asked them to tell me who else was in. “Nine Inch Nails, Cypress Hill, Aerosmith, Guns N’ Roses.” I said, “Man, that’s not Woodstock—that sounds like nothing but white guys. In ’69, we had Joan Baez, we had Richie Havens and Sly. What happened to women, and where are the black people?” I believe those are the questions that Bill Graham would be asking if he had been there in ’94. I told them if it was going to be a Woodstock you can’t have just one color of the rainbow, you have to have them all. They heard me—they added black and female performers, and we played Woodstock again.

In ’99 they tried it one more time, but the message was gone—no more peace and love. By then, for the experience to be true to the original Woodstock, they would have had to invite music from all over the world—Native Americans, African people, Chinese people—like the Olympics but without the competition. In ’99, it was about just one kind of music and soft-drink sponsorships and the TV broadcast. It was about corporate stock, not Woodstock. I didn’t play at that one—no way.

In 2010, we did a concert with Steve Winwood in Bethel, New York, just a few hundred yards away from the original Woodstock site. I had just proposed to my wife, Cindy, a few days before, and I was on such a high. I had a free afternoon, so I went to walk around what used to be Max Yasgur’s farm—you can still go there and see the field where five hundred thousand people gathered. It was a very emotional experience for me. They now have a museum there—and there were some people visiting who had seen Santana play that afternoon. “We were here the first time—it’s great to see you again,” they said. It was so gratifying to go back there and hear that.

To tell the truth, I think a lot of my memories of what happened onstage at Woodstock have been shaped by seeing myself in the movie, which didn’t come out until almost a year later. The first time I saw the movie was when Santana was back in New York City in 1970. I remember I liked the way the director showed all the stuff that was happening by dividing the screen into three parts, but I hated that wide-angle lens he used that made me look like a bug.

Devon Wilson, Jimi Hendrix’s girlfriend, took me to see the movie the first time. She told me that when she had seen the movie with Jimi, it had totally messed him up. “When the part with you guys came on, you should have seen his face. He couldn’t stop talking about Santana.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. Jimi really liked your performance, man. He loved the energy.”

I had another conversation with Devon not long after Jimi’s death, and she really shocked me when she told me that Jimi had once said he would have liked to have been in Santana. I still get dizzy thinking what that would have been like!

I think our music was really crisp at Woodstock, and with so many other kinds of bands playing there, I can see that we would have stuck out. Shrieve was really on that day, like a horse running free, and Chepito was playing his timbales with absolute conviction and fire, giving those hippies a taste of a kind of music they’d never heard before. We were rehearsed, like a car ready to hit the track—some of the other groups were discombobulated and still in the pit, waiting to get it together. We were hippies, but we were professional in our way. Also, some of the other groups suffered when it rained after we played—I remember talking with Jerry later, and he told me that the stage was wet when the Dead played and that their guitar cables were shocking them, so they couldn’t really step on the notes. They had no insulation and no ground, so it was literally like putting your finger in an electric socket. Who can do a show like that? Jerry said that it was the worst they ever played.

If you ask me, from what I heard on the album and saw in the movie, there were three acts that had it together in terms of their music and their energy. Sly was number one—he owned that whole weekend. Then it was Jimi Hendrix, with the amazing way he presented the national anthem and the rest of his show, even though most of the crowd had left by then and it was already the middle of Monday morning when he played. Then there was a bunch of groups fighting for third place—but I think it was either the Who or Santana, and that was it.

We didn’t stick around to see the rest of the festival after our show—it was time to go. The helicopters were flying people out to make room for the bands that were coming in—it was chaotic, and it wasn’t like there was a backstage where you could just hang. I was still tripping and wanted to go and hibernate. The other guys were talking, but I kept quiet—I was afraid someone was going to say something about my playing out of tune. We had had enough, man. We ended up hanging out for a while in the lobby of some Howard Johnson–type hotel away from the festival, and then it was back on the road.

Woodstock was important to Santana: it was the biggest door we would ever walk through with just one step. But until I saw the movie, Woodstock had in many ways just been another gig, and for us 1969 was a summer full of big shows. After Woodstock we played pop festivals in Atlanta, New Orleans, and Dallas. We were on the road for another two weeks before we got back home, so you can imagine that by then it was all fading away in my mind.

I’ll never forget two amazing things from those national tours. The first happened in Boston, where we played just after Woodstock at the Boston Tea Party. We were walking around Cambridge when suddenly we heard “Jingo” on the radio. A rush of energy went through my body when I realized that it was our song. Of course we all started talking about it, and then the excitement shifted to: “Man, it sounds like crap—we got to get a real producer.” It was true—the music sounded really thin. You just couldn’t feel our energy coming out of a little radio speaker. That was an important lesson—to think about how people would be hearing our music. “Jingo” was our first single, but it didn’t get picked up by many stations, so Columbia went with “Evil Ways” as the second single, and that took off later.

The second thing happened when we played a few shows in October in Chicago. It was our first time in that city, and for me Chicago only meant one thing—it was the home of the electric blues! We had a day off, and we were staying at a Holiday Inn. I heard that Otis Rush was playing on the South Side in a rough part of town—it might have been at Theresa’s Lounge. I couldn’t persuade anybody to go with me. “No; today’s a day off, man. I’m going to get a hamburger, then go to my room and relax.”

So I persuaded a cab driver to take me there, and I went by myself. As soon as I got out of the cab, I was like, “Oh, damn. This is a danger zone.” It was deep, deep ghetto—I felt people looking at me like I was a pork chop and they were a bunch of sharks. I quickly stepped into the small club, and there he was—Otis Rush, looking so cool, wearing shades and a cowboy hat, a toothpick in his mouth. I stood by the bar and couldn’t move. I was just listening to his voice and looking at his fingers on that upside-down guitar. I had the feeling that this was just another night for him, that he did this every night he played, but seeing him there—playing with a real Chicago rhythm section, showing me how it’s done and why it’s done—was so different from seeing him anywhere else. For me, there was still nothing else that came close to the feeling that comes from the heartfelt blues—that music was just zipped into my pores. To hear Otis Rush like that, I was ready to go to Vietnam or Tehran or Pakistan. To hear that music, I’d go to hell and make a deal to stay there.

I stood out like a sore thumb in that bar with my long hair and mustache and hippie clothes. I noticed everybody looking at me. Then I saw a policeman talking to the bartender, so I walked over to him. “Excuse me,” I said quietly. He looked at me up and down. “Yeah?”

“I have a hundred dollars for you—can you keep an eye on me? Let me hear Otis, and when he’s finished, can you ask the bartender to call a cab and help get me to it?”

“A hundred dollars? Show it to me.”

I showed him. “Okay, be cool, man. Relax and enjoy it.”

I did, until the end of the very last set. Otis unplugged his guitar, said, “Thank you, ladies and gentlemen—good night!” and split. The cop looked at me. “You ready?” The bartender called me a cab, he walked me over to it, and I paid him for hanging with me. It was worth every cent. I didn’t see the streets or feel the bumps driving back to the hotel. I was still hearing the music—the profound sound of Otis’s voice and the way he bent the notes. Catching Otis and other blues guys like Magic Sam and Freddie King, who still played in small bars around Chicago, became part of every visit.

I think Brother Otis will always bring out the seven-year-old child in me. I’m not the only one who feels that way—Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page do, too. Even Buddy Guy will give it up for Otis. I remember one time in 1988 I got into Chicago around five o’clock and was checking in to an airport hotel. The phone was already ringing in my room when I put the key in the door—it was Buddy. “Hey, Santana! Listen, Otis and I, we’re waiting on your ass here. You got a pen? Write down this address and come on over.”

The address was that of the Wise Fools Pub, and I didn’t waste any time. I got there early enough, when the place was only half full—Otis hadn’t actually showed up yet, so Buddy and I took some solos, and we were just killing it. Then suddenly I saw that cowboy hat and toothpick come out of the shadows. It was like a scene in a movie. Otis looked around and walked through the crowd like he was in no hurry at all. This was his turf. He grabbed his guitar and stepped into the single spotlight, which hit his face in a very dramatic way. He leaned into the microphone and said: “Give them a hand, ladies and gentlemen!” Then quietly, almost to himself, he said, “Stars, stars, stars…”

It was like Otis was saying, “Oh, yeah? You think these guys were good?” He plugged in and didn’t even sing—he just went straight into round after round of an instrumental blues that showed us who the star really was. He was in the middle of a solo and hit a lick that had Buddy and me screaming like shrimp on a Benihana grill. We couldn’t believe what he was able to get out of each note. It was like getting a real long piece of fresh sugarcane and peeling it with your teeth to get into the middle, where the sugar is, and the sound it makes when you suck the sap out of it and the juice starts running down your chin and onto your hands. That’s what it was like when Otis was hitting those notes—nothing sounds or tastes better than that!

Over the years I’ve gotten to know Otis and let him know how important his music is to me. He’s not one for compliments, though—the first time we met at the Fillmore, I told him how incredible he sounded. His reply was, “Man, I got a long way to go.” What—you? The guy who made “All Your Love (I Miss Loving)” and “I Can’t Quit You Baby”? I think he’s just one of those brothers who has a hard time validating his own gift, who’s distant in his mind from his soul—except when he’s playing. Not long ago Otis had a stroke, and he can’t play anymore, and I make it a point to stay in touch, send his family a check twice a year, and let him know how much he’s loved. He was never really one for words, but he’ll still get on the phone and say, “Carlos, I love you, man.” What can I say? He changed my life.

Back in the Bay Area in December we got asked to play another festival. It was at the Altamont Speedway—and I don’t think I’ve ever been happier to be the first band to go on, then or now. Now that I look back on it, I think that while Woodstock was as close to spiritual as you could get, Altamont was about overindulgence and cocaine and strutting your stuff to see how badass you were. It wasn’t about the Rolling Stones hiring the Hells Angels, though that was part of it. It was just a strange, rowdy kind of vibe—people pushing instead of relaxing, getting upset with each other, just the wrong kind of energy, and the people who were supposed to stop that from happening were getting the most pissed off. It smelled bad, and there was fear and anger. You could see it in people’s eyes. We played and left before it all got weird—later we heard that someone in Jefferson Airplane got knocked out and that the Dead didn’t want to play and that the Rolling Stones went on and a man got killed.

You can see it in the movie Gimme Shelter—it was all so tangible. The Stones wanted us to be in their movie, and I think we were all pretty much in agreement that we didn’t want any part of that. It put everything in a bad light—the atmosphere was dark and brutal and cruel, and we didn’t want to participate. We said no—more than just bad vibes, that experience had a tangibly dark, scary, cruel kind of energy that we didn’t want to be connected to. We’re still saying no today, because every once in a while they want to bring it out again with more footage.

If ’69 was about volume and overindulgence, another part of that year was about speed—things kept happening faster than ever for Santana. How fast? By November, when we came back to New York to play the Fillmore East, we were headlining—the Butterfield Blues Band and Humble Pie were opening for us. There’s a letter from that same month that I got to see years later, sent by Clive Davis at Columbia to Bill Graham, asking him to start booking Miles Davis into the Fillmores and introduce him to the rock audience. In the middle of it, he wrote about the strong sales of Santana and called us “unstoppable.” In December, “Evil Ways” was released, and by early ’70, it was a top ten radio hit. Then we got ready to go into the studio again, and after that, as Clive said, Santana really was unstoppable.