CHAPTER 11

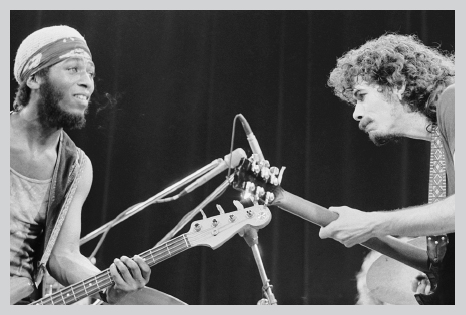

David Brown and me at Tanglewood, August 18, 1970.

I know jazz puts certain people off. I think when it comes to some jazz, people pay attention to the tools instead of the house. When you hear music, you don’t want to see the tools. You don’t want to know how many nails it took to build the house. Some people just haven’t heard Kind of Blue yet, or A Love Supreme. They haven’t heard Wayne Shorter’s music.

Until I knew about Miles and Coltrane, I listened to jazz without calling it jazz—groups I heard live, or maybe a hit on the radio. I liked Chico Hamilton and Gábor Szabó and Wes Montgomery, but if anyone said the word jazz, I didn’t want to listen to it. That word made me think about bands in tuxedos playing while people who were also in tuxes ate dinner. It didn’t have fangs and teeth and claws. I wanted stuff that scratched you.

It was Michael Shrieve who got me to listen to Miles and Trane and corrected my twisted perception that jazz is only for old, fuddy-duddy people. He went through my record collection and saw what I didn’t have, and he decided I had to hear Miles and Coltrane. So he brought over a big stack of records for me. I started to listen—“Whoa, what is this shit? This is really different from John Lee Hooker.” I started playing it back and forth. Miles and Trane. Miles and Trane.

I started to get Coltrane inside of me with Africa/Brass and the 1962 album Coltrane, which included “Out of This World,” and of course A Love Supreme. With Miles, In a Silent Way and the Elevator to the Gallows sound track started it for me, then Kind of Blue.

I would look at Shrieve and say, “Wow, this is the blues? And this is the same guy who did Bitches Brew?”

“Yeah, same guy.”

I was like, “Oh, damn.” I was able to feel what Miles was doing with modal jazz. You could just sit in one groove and make it happen. After a while, his music became more endearing, closer to me—I got more into it because his path really was a story, all the way back to his first records with Charlie Parker.

The album that really, really opened it up for me was Miles’s Bitches Brew. It had long tracks like “Pharaoh’s Dance” and “Spanish Key”—on that one I could hear the connection to his Sketches of Spain album. Those tracks made you want to turn the lights down. One writer called it “a light show for the blind.” It was very visual music. It made so much sense with everything that was happening then—like a man walking on the moon. When it came out I played it nonstop, nonstop, nonstop. I read Ralph J. Gleason’s liner notes over and over—the notes in which he said that after Bitches Brew, the world would never be the same. Not just jazz—the world.

During the first part of 1970, we played Europe a few times—the Royal Albert Hall in England, venues in Germany, Denmark, and Holland, and the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, where I met Claude Nobs for the first time. Claude was one of the first people I could respect the same way I did Bill Graham—he had persuaded the government and local businesses to invest in his idea to start a jazz festival, and it quickly became one of the music world’s crown jewels. I could tell Claude liked us a lot, which was a good thing, because even though we had played on the same bill with jazz groups, it had always been for a rock audience. This was different, because this was really a jazz festival. We were the strangers there, playing for the people who came to hear Bill Evans and Tony Williams Lifetime and Herbie Mann, when he had Sonny Sharrock on guitar with him.

Claude made it work. He asked us to play outdoors next to the pool, not inside the casino, where most of the big concerts happened—that’s the casino that burned down and that Deep Purple sang about in “Smoke on the Water.” We did as Claude asked, and it was the first place in Europe where I felt a camaraderie that was even more pleasant than the feeling I got from hanging with hippies at the old Fillmore. At that time, people who were different from one another—who came from different generations and wore different clothes—were usually very guarded and polite around each other. In Montreux, it was loose and free—all sorts of people were hanging together, having a great time.

I played Montreux so many times over the years and did so many special shows there that it was really like another home. Seriously, if I could make three or four of me, one of them would live in Switzerland and just soak up the vibe over there. Claude and I quickly got tight, and Santana played there more than a dozen times. Every time we got there he’d open his home to us and show us his collection of recordings and videos—it was like a music museum up there, high in the snowy mountains looking out at the world. Claude was a friend and a collaborator—if I wanted to try something new, he would help make it possible—a concert with John McLaughlin; a blues night with Buddy Guy, Bobby Parker, and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Or the event we did in 2006—we invited African and Brazilian musicians for three straight nights, which was like a festival within a festival. We called it Dance to the Beat of My Drums after a song by Babatunde Olatunji, who also had given the world “Jingo.” If I wanted to keep playing for three hours, it was cool with Claude. I think it’s important that he be validated in every way possible for all that he brought professionally and personally to musicians—we need more musical laboratories like Montreux, where musicians can come and be open, collaborate, and experiment.

I was still shy onstage then. I didn’t say much into the mike, and I wasn’t doing interviews. But if I wanted to meet someone I was fearless. When Santana played New York City in August—our third time there during 1970—I got to meet some of my biggest heroes, people who were resculpting the musical landscape. Nobody was bigger in my eyes than Miles Davis.

Bill was booking a summer weekend up in Tanglewood—an outdoor festival in Lenox, Massachusetts. It was all rock bands except on Sunday, when he put us on a bill with a big group of singers called the Voices of East Harlem as well as Miles Davis—jazz, gospel, R & B, and Santana. This was Bill’s genius—he created that multidimensional environment consciously and honestly and brutally, and he got a new generation to hear the beauty in all this music. And that was the deal: if you want to hear Steve Miller or Neil Young or Santana, you’ve got to hear Miles Davis. We need more promoters like that today: if you want to hear Jay Z or Beyoncé, you have to hear Herbie Hancock or Wayne Shorter. Wouldn’t that be incredible?

We went up to Tanglewood, and I remember getting there and meeting a photographer who was selling big black-and-white prints of Miles and Ray Charles performing at the Newport Jazz Festival. I bought some, and just as I’m carrying them backstage an amazing yellow Lamborghini drives in, and Miles gets out. I wasn’t afraid, so I went up to him.

“Hi; my name is Carlos—would you be so kind as to sign this for me?” He looked at me and looked at the photo, grabbed a pen, and signed “To Carlos and the best band” or something like that. He knew who I was, so we started talking, and after a little while he said he had something for me. He went into his shoulder bag and pulled out a tube that looked like a big eyedropper wrapped in cowhide, and of course it was cocaine. Miles looked at me and said, “Try it.”

I hadn’t slept the night before, I’m with the Miles Davis, and I did something that I later felt I shouldn’t have done. Cocaine put a distance between my heart and me, between me and the music. My body rejected cocaine as something that made my soul feel disenfranchised—it would say, “This is not for you.” When I remember that Tanglewood performance, I still cringe because it felt like I couldn’t get myself into the center of my heart. It wasn’t the same problem I’d had at Woodstock, but I have the same kind of regret. I decided again to make it permanent: I’d never take what someone else gave me, no matter who it was.

Tanglewood had a beautiful audience with all kinds of people, many of whom, as they had at Woodstock, came up from New York. The festival was much, much smaller and was run much tighter. There were only three bands that Sunday. I loved the Voices of East Harlem. They were all about power to the people and positive message music, and they had that black church energy. There’s also something about a hip choir, you know? Donald Byrd and “Cristo Redentor”; the Alice Coltrane albums, with their heavenly voices; Duke Ellington’s Sacred Concerts. I think it’s the prayer feeling about them that I like—the sound of voices together going straight up to God. If it has a funky, African feeling in it, I can never put it aside. The Voices had a great bass player, a young guy with a huge Afro—Doug Rauch. I called him Dougie. He became a good friend of the band and even traveled with us before he joined us. He had a nice, burly sound on bass, like an older, acoustic tone, but with a Larry Graham technique—slapping, funky. He was part of a new wave of bass players that included Chuck Rainey and Rocco Prestia with Tower of Power and Michael Henderson with Miles—they were all moving the music forward and playing music that wasn’t just R & B and wasn’t completely jazz. They were all supremely important to Dougie. The next year he moved out to San Francisco and ended up playing with the Loading Zone and Gábor Szabó and finally Santana.

At this time, Miles’s band was getting big with the rock audience. Other jazz musicians had played for hippies, but I think the difference with Miles was that he had been listening to rock and funk groups and was bringing his music closer to rock. Without a shadow of a doubt Betty Mabry, who was his wife then, was a big reason for this. She helped transfigure her man. She got him out of those Italian suits and into leather trousers and platform shoes. She didn’t want to hear any old, mildewed music at home, so she got him listening to Sly and Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, the Chambers Brothers, and the Temptations. His record collection started to be broader—as they say now, Miles expanded his portfolio. I’m pretty sure Betty turned him on to Santana.

Another thing was that, like Betty, most members of Miles’s band were closer in age to the hippies than they were to Miles. You can hear that in the way Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland played; you can hear that they had been listening to Sly and Larry Graham and Motown. Some of them were starting to use fuzz tone, and Chick was using a ring modulator. Even Miles was using wah-wah and echo.

When I heard him in Tanglewood, Miles’s music was already changing from Bitches Brew. His group played a song called “The Mask” that made you feel like you were in an Alfred Hitchcock movie—something’s about to happen, and you can’t get out of the way. Miles’s bands were masters of mystery and tension—they never played anything mundane or obvious. It was like what my friend Gary Rashid told me once—he agreed that Miles was a genius, but he said a big part of that genius was Miles’s habit of surrounding himself with four or five Einsteins. The music always depended on who was in the band—also on what they ate and what they were thinking that day and what was going on between them.

I began to keep track of all the musicians who played with Miles—my own little list in case I got lucky enough to play with any of them somewhere down the line. At Tanglewood, Miles still had Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette with him as well as Gary Bartz, Dave Holland, and Airto Moreira. By the end of the year, the band started to change—Jack, Dave, and Chick were gone, and Michael Henderson and Ndugu Chancler were stirring the pot. Keith had stayed.

Keith’s amazing, man. I have to say something about him for a minute. He’s just fucking unbelievable the way he can create right on the spot. You can tell by the way he sits at the piano and improvises a whole solo show. To me, he represents a brand-new soul coming to this planet with no fingerprints, no preconceptions, no preconceived notions of what music should be. He’s a giant of innocence and courage to be able to come in with a blank mind and sit down and play the way he does. I’m totally the opposite—I honor myself with melodies. I have to have some kind of melody that I can dismantle in different ways; then I try to refine it and present it the best way I can. I collect melodies like a bee collects pollen—“The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”; “Wise One”; “Afro Blue.” To hear a person who discards all of them and gives you something that’s 100 percent fresh—that’s why I love Keith so much. What he does honors music: he goes onstage absolutely not knowing what he’s going to do.

I’ve studied and listened to so many tapes of Miles’s bands from around this time that I could tell how the sound of any given tune would be different each time they played it. The rhythm was always flexible, and the music always seemed to match the players. When Wayne Shorter was with Miles, the music sounded perfect for his horn. When Bartz came in the music sounded like it was a comfortable fit for him, too.

Miles knew what he was doing even when he didn’t know beforehand what was going to happen. He was playing for a young rock crowd, and he knew he was bringing his music onto their turf, but rock bands could not come into his jazz world. He wasn’t shy about it. I met him for the first time that day in Tanglewood, and we got to be very close. Later he used to tell me, “I can go where you guys are, but you can’t come to where I am.”

Miles was right. We didn’t understand harmonically or structurally what he and his band were doing. That took years and years. They had another kind of vocabulary, which came from a higher form of musical expression. It came from a special place—from Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane—and at the same time it was deep in blues roots and expanded into funk and rock sounds. The sound of Miles back then was a microscope that showed everything that had happened before in jazz and a telescope that showed where the music was going. I was blessed to be around and to hear this music when it was happening. I think if you start by listening to the music he made when he played for Bill Graham at the Fillmores, you can hear how Miles helped people expand the boundaries of their consciousness—his music put stretch marks on their brains.

There’s a story I love to tell about Bill and Miles because it says so much about each of them and about their relationship. I call them both supreme angels because of what they did for me and their impact on my life—and because the way they lived their lives was an example to everyone. They were both angels, but they also had feet of clay. They were divine rascals.

I first heard this story from Bill. The way Bill told it, after he got that letter from Clive Davis asking Bill to start booking Miles at the Fillmore—the one that calls Santana unstoppable—Clive left the job of persuading Miles to Bill. Bill already loved Miles, but who tells Miles what to do?

Miles couldn’t get into the idea at first. A lot of it was about the money. Bill offered him a different kind of deal from what he was used to in the jazz clubs, where he would play for a whole week. So Bill made it more attractive financially for Miles. Bill also made the argument that Clive was making—that it’s an investment in the future. If Miles played the Fillmore, his name would be on the marquee next to rock bands and he’d be getting through to new listeners—the hippie crowd. It might not mean so much right away, but the following year he’d double or triple his audience and then double or triple his record sales.

Bill finally persuaded Miles, got him into the schedule, and told him, “I have these dates open, and you’ll open up for so-and-so and so-and-so.” Bill’s thinking was that even though he respected Miles he could not let him be the headliner. All those hippies coming to hear Neil Young or Steve Miller or the Grateful Dead would not stick around for Miles, and he wanted to be sure they heard Miles. He wanted Miles to go on first so he’d be sure to have a full audience, even if it looked like Miles was opening for them.

Miles did not know these bands—their music did not resonate with him, and for whatever reason he didn’t see himself opening up for them. So Miles showed up late for his first show at the Fillmore East. Really late. Neil Young was the headliner, and Steve Miller was on the bill, too. Miles was so late that Steve Miller had to play first, and they were getting ready to ask Neil to go on. Somebody got through to Miles and got him to hustle down to the club.

I remembered how Bill would be if a band dared to show up late—he would stand with his arms folded across his chest. When Miles got there, Bill was looking at his watch and looking at Miles.

Miles played it cool—“What’s up, Bill?” Miles knew he had him. Bill had made the mistake of telling him that Sketches of Spain was his number one album of all time, the one album he would take to a desert island. The redder Bill got, the calmer Miles was. Bill wanted to let loose some of that New York language that he had educated me with, special words like schmuck. But he couldn’t. This wasn’t some teenage rock group. This was Miles Davis.

Finally Bill let it out. “Miles—you’re late!” Miles looked at him innocently and said, “Bill, look at me. I’m a black man. You know cab drivers don’t pick up black people in New York City.” What could Bill say, right? Meanwhile, Miles had his Lamborghini parked around the corner. Bill probably knew it even then.

After we met in Tanglewood I would see Miles almost every time we played New York City, sitting right in the front row, wearing something flashy, with a fine woman in the seat next to him. He would call me to hang out—he’d find out where I was, track me down, and the phone would ring. “Didn’t I tell you never to come to New York without calling me first?”

“Hey, Miles—what’s up?”

“Whatcha doin’?”

What was I doing? It was three in the morning. “Oh, just having fun and learning.”

Miles also liked to hang out with Carabello—they would get some cocaine and get into it together. I remember a bunch of us from both groups were together at a 5th Avenue hotel—it was Keith Jarrett, Shrieve, and I in the elevator, holding it and waiting on Miles and Carabello, who were getting something from a dealer in the lobby. We were waiting and waiting, and Shrieve turned to Keith and said, “How do you do it?” He meant, how did Keith put up with all the cocaine and stuff? Keith said, “Like this.” He snapped his fingers. “I just turn it off, like a button.” I remember thinking, “Whoa—what button is that?” I wondered what it would take for me to turn off the cocaine conversations in Santana.

Miles and Carabello finally got on the elevator, and when we were going up Miles looked at me and out of nowhere said, “You gotta get you a fuckin’ wah-wah—I got one.” He wasn’t taking any argument. The thing is I already used a wah-wah on some Santana songs, such as “Hope You’re Feeling Better,” but it wasn’t something that was onstage with me. But the way Miles said it, it was like, “Come on—keep up, man.”

Miles was right—Hendrix had used it, then Clapton with Cream, and Herbie Hancock had it in his group. After a while it felt like any band in the ’70s had to have a wah-wah and a Clavinet or some kind of electric piano. I obeyed Miles and started using a wah-wah in all my live shows. I remember looking at Keith as Miles was giving me that advice, and he just rolled his eyes.

I got a lot of advice from Miles over the years. A few years later, after we hadn’t been in New York for a bit, he called me. “What are you doing now?”

I said, “We’ve been on the road for a while, so we decided to take a break, record an album, and replenish.”

“Well, don’t stay out there too long, man. You don’t want to lose the momentum. You’ve got it going, so don’t stay off the stage too long.” I said, “Okay.”

Another time, Miles told me, “You can do more than just ‘Black Magic Woman.’”

“Thank you, Miles. I’ll give it my best shot.” It wasn’t a spanking, it was an invitation.

I know Miles went out of his way a lot of times to find me and teach me the ropes, tell me when to duck, stay away from this, and have you checked out that? I don’t know how many other musicians Miles showed that side of himself to, but I got the feeling not many. The more I’ve read about Miles, and the more I’ve talked with other people about him, the more surprised I became that he would sometimes drop his guard and mentor me. Because Miles usually would get very intense, and he could read people, and if he saw that he could ride someone, he would mount that person psychologically. I saw him do that to a lot of people.

Miles could push it too far. There’s a story that Armando Peraza told me after he joined Santana. Armando was one tough dude—he came up from Cuba in the ’40s and played percussion with Charlie Parker and Buddy Rich almost immediately after he made it to New York City, and he had no problem going into the roughest part of town to collect money that somebody owed him. One time Armando was playing with George Shearing at the Apollo, and Miles was on the bill, too. Both Miles and Armando were kind of pint-size—when they met, Miles started messing with him in his usual way, and Armando got him in a corner and told him in his accent, “You doan wanna mess wid me. I break you jaw—you never fuckin’ play trompet again.” I can see the words Miles was thinking in a balloon over his head—“Uh-oh. That motherfucker is crazier than me.” Miles was smart—he knew when to back down.

I liked to use the term “divine rascal” to describe Miles. I later heard that around this time, Gary Bartz knocked on Miles’s hotel room door and said, “Miles, I got to talk to you. I can’t fucking play anymore—that Keith Jarrett is fucking up my solos, playing all the wrong shit, never backing me up. I’m going to quit, man.” Miles said, “Okay, I got it. Tell Keith to come over.” So guess what he tells Keith? “Hey, Bartz just told me he loves what you’re doing: do it some more.”

Sometimes we’d run into each other. One night I was hanging backstage at the Fillmore East checking out Rahsaan Roland Kirk playing flute on Stevie Wonder’s “My Cherie Amour.” Fwap! Someone flicked my ear from behind me—really hard. I’m thinking, “Oh, man—that fucking Carabello…” I turn around and fwap, in my other ear. I turn again and there’s Miles running away, almost to the elevator. He saw that I saw him and came back slowly, grinning. He said, “What you doin’, man?” I rubbed my ear. “I was listening to Roland Kirk.”

He said, “I can’t stand that n .…” He used the n word.

“Oh?”

“He plays some corny-ass shit.”

I was thinking, “Okay, that’s between you two, because I like Volunteered Slavery.”

Miles was way ghetto. I don’t think he cared so much about what other people thought about him or about what he said, but a lot of times he used words just to fuck with people’s heads. Once I asked Miles if he liked Marvin Gaye. “Yeah—if he had one tit, I’d marry him.” He called Bill Graham Jewboy, and Bill would just go, “Oh, Miles.” Bill wouldn’t take that from anyone else—not Hendrix, not Sly, not Mick Jagger. Later he’d come up to me and say, “Can you believe the way Miles talks to me?” I knew underneath it there was mutual respect, but I still couldn’t believe how Bill’s macho thing could melt away that easily with Miles.

People could be envious of him—even scared. He made some people angry and feel hurt. Some people saw Miles as abusive toward white people. I never saw that. I thought he just abused everybody.

Backstage at the Fillmore I changed the subject. Jack Johnson had just come out, so I said, “Miles, man—your new album is incredible.” He looked at me and smiled. “Ain’t it, though?”

I met two more heroes in New York that summer of 1970, both of whom connected with Miles—Tony Williams and John McLaughlin. Tony played drums with Miles through most of the changes of the 1960s and on an album I loved, In a Silent Way. He was leading his own group, Tony Williams Lifetime, with John McLaughlin on guitar and Larry Young on organ. It was like all roads led to Miles—Larry and John had also played with Miles on Bitches Brew.

Lifetime was playing Slug’s, a small, run-down club on the Lower East Side. This place was like something in a war zone; it was the club where the trumpet player Lee Morgan would get shot the following year, and they’d close it down for good. I was walking across Avenue A or B, and some guys were sizing me up, like, “What’s this hippie freak up to down here?” John told me he went through the same thing—“Where are you goin’, white boy?”

“I’m going to go play with Tony Williams.”

“Tony Williams? Man, we’ll walk you there. You can’t walk alone here. They’re going to take your guitar.” John’s story gave me the same feeling I had when the bus driver in San Francisco had me sit with him that time I was carrying my guitar. We all have our angels.

Man, the Lifetime show was loud and mind-boggling. It fried my brain. I had never heard rock and jazz ideas put together with so much intensity and with the volume turned up all the way like that. Slug’s was a small, narrow place, and Lifetime filled it with a vortex of sound. Cream sort of had that energy, but not with the same ideas or sounds—it didn’t surprise me so much that Cream’s Jack Bruce joined Lifetime a little while later.

The three of them had an attitude that made them look like enforcers. You almost didn’t want to look at them they were so… menacing. John was killin’ brilliant in his playing, and I know that just as he scared me, I’m sure he scared even Jimi Hendrix. It was like, “Holy shit, he’s got the Buddy Guy thing down and he can take care of the Charlie Parker thing.” There are just not that many musicians who can play fast and deep the way he does. Even today I love to jam with him, then step back and just listen to him soar.

I met John when they took a break, and he recognized me right away. “Santana? Nice to meet you.” Around a month before, I had gotten into Wayne Shorter’s album Super Nova, which had Sonny Sharrock and John on some tracks, so that was the first thing I told him. “I also love what you do on Joe Farrell’s ‘Follow Your Heart’ with Jack DeJohnette.” I think I surprised him a little with what I was listening to, and then he told me what he was into: Coltrane, Wayne, Miles, and Bill Evans—in that order. That’s all we needed to talk about. John wasn’t into Sri Chinmoy at that point, but Mahavishnu was right around the corner.

I didn’t get to talk to Tony or Larry that night, but I would get to know them later, along with many other musicians who played with Miles, including Jack DeJohnette. It was Jack who told me that he suggested John leave London and move to New York City—John, like Jimmy Page, was a session guitarist at the time, and Jack had heard him playing here and there. I always wondered, though, about Tony leaving Miles, which seemed like the perfect gig for him, and then Miles using his new band—John and Larry Young without Tony—on Bitches Brew.

I never asked Tony about that, but I think I can hear the reasons on a live gig at the Jazz Workshop in Boston in 1968, not long after he played with Miles on In a Silent Way. It sounds almost like he’s having a tantrum on the drum kit—like he’s a little kid throwing stuff from his high chair onto the floor. Meanwhile Miles was cool, and so were Wayne and Chick. I would have fired him. I really don’t know what happened that would make someone do that, but he was certainly sending a strong signal.

Tony needed his own band—that’s something I would see time and time again in other groups, and in Santana, too.

In the Bay Area in August was the first time Jimi Hendrix and I really spoke to each other as musicians, but that wasn’t the first time we met. Back in ’67, the week after our band was fired by Bill for being late, Carabello had somehow got us into that Fillmore show to meet Hendrix. We were trying to duck Bill, and we didn’t have any money—we got in just as the sound check was starting. It didn’t matter about Bill anyway, because he had his hands full with amplifiers that wouldn’t cooperate. Everything was feeding back, screeching like electrified pigs. They finally got it together, and we were backstage just before the band was going on. Jimi and I hadn’t said anything between us except hello, and suddenly everybody went to the bathroom—everybody. Somebody said, “Hey, man, you wanna come and join us?” I was young, but I knew what they were doing. “No, man. I don’t want to do any coke.”

“You sure? It’s from Peru, really first class.”

“You go ahead, man. I’m there already.”

That’s when I started to use my mantra about partying too much. “I’m there already, man. I don’t want to get past it.”

Then Jimi played—and it was incredible, both shows that night. I couldn’t believe it—the way he could will his guitar to make those sounds. They didn’t sound like strings and amplifiers anymore—his sound was intergalactic, with spectral frequencies that were notes yet so much more. At times it sounded like the Grand Canyon screaming.

I was like, “Holy shit.” Gábor was on the bill, too, and that first night he sounded good, but I know for a fact that Gábor never wanted Hendrix to open for him again. He told me so when we were living in the same house for a while in 1971 and almost started a band together. That was the impact Hendrix had—he came and marched across the landscape like a conquistador wielding lightsabers and lasers, weapons that no one had ever seen or heard before. I saw him around seven times total, and that night was great. But no Hendrix show topped the one I heard him do at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds in San Jose in ’69. I never heard him do better.

The second time we met was sometime in April of 1970 in New York City. Devon called me from the lobby of our hotel and said, “Come on down. I want you to come with me to a party.”

“What party?” I thought we were going to go somewhere else, hear some music.

“Man, just come on down—we’re going to a Jimi Hendrix party. He’s recording.”

That sounded so strange. “He’s recording and having a party? When I record I don’t want anybody in the studio.” Devon just laughed. “Come on, don’t be such a square. We do it differently over here in New York.” Devon had taken me to see the Woodstock movie the day before, and now we were going to the Record Plant. Okay, why not?

We got into a cab and got to the studio just when Jimi was arriving with a blond lady who, the last time I saw her, was with Tito Puente. Small world. Jimi opened the door for us and looked at me. “Santana, right?”

“Yeah. How you doing?”

He paid for both cabs, then looked at me. “Man, I like your choice of notes,” he said with a smile.

I said the best thing I could think of at that point. “Well, thank you, man.”

We walked into the studio, and it was packed with people. “Hey, how you doing?… What’s happening?… How you doing, man?” As we walked from the front door down the hallway to the studio, there was a buffet of shit laid out on a table—I mean hashish, grass, cocaine. Really—it was a buffet. Jimi was ahead of me, running his hands through it, sampling stuff. He looked at me and said, “Help yourself, man.”

“Thanks—I’ll just smoke a joint. That’s great; thank you.”

Jimi and his engineer, Eddie Kramer, got started right away, talking about picking up where they had left off the night before, doing a song called “Room Full of Mirrors.” I’m looking and listening, wondering how they do it in the studio—what can I learn? They played back the song, and I heard Jimi singing, “I used to live in a room full of mirrors / All I could see was me…” Then Eddie said, “Go ahead, Jimi, here comes your part.” They were overdubbing a slide guitar part. Jimi started playing, and for the first eight bars he was right with it. By the twelfth bar, it had nothing to do with the song anymore. It would have been okay if he were just blowing over a groove, but this was more a structured song. I was looking around to see how other people were hearing this. Eddie was looking worried, and he had actually stopped the recording, but Jimi kept playing—more and more out.

Jimi was facing away from the window to the control room. Eddie told one of his guys to check on him, and I swear the guy had to physically pull him away from the guitar and the amplifier. He got Jimi up, and when he turned around—I’m not kidding—Jimi looked like a possessed demon. It almost looked like he was having an epileptic attack—foaming at the mouth, his eyes red like rubies.

I remember that the whole experience drained me—and that a feeling of questioning came over me: “Is this how it’s got to be done? There’s got to be a better way.”

The last time I met Jimi was a few weeks later in California, when he played the Berkeley Community Theatre. He had made a change on the bass and was using Billy Cox, not Noel Redding. We caught the concert and went back to hang with Jimi at his hotel. Something told me that Jimi needed help, so I decided I should bring the gold medallion I wore around my neck, which my mother had given me when I was a baby—the kind that all Mexican mothers give their children for protection: Jesus is on one side, and the Virgin of Guadalupe is on the other. I was thinking I’d just grab Jimi’s hand, put the medallion in it, and say, “This is for you—wear it, because I think you can use it.” When we got there, Jimi opened the door and I could see that he was wearing six or seven of these medals already, so I kept mine in my pocket.

A few months after that, Santana was playing in Salt Lake City when we heard that Jimi had died. That night you could hear all the toilets on our floor of the hotel flushing—people dumping all their shit, so angry because we heard he had OD’d. Whether or not it was true, he was the first of our generation to go, and we were sure drugs had something to do with it. That’s how we put it. “Fucking drugs, man.”

I don’t think anybody came through the ’60s without taking some drugs. I also don’t think anyone came through the ’60s without changing—but some people changed a little too quickly. Who can tell someone who’s twenty-one, twenty-two, or twenty-three to slow down? I turned twenty-three that year, and it felt like all the planets were aligning and there was a divine explosion. The Woodstock movie came out, and a few weeks later, in September, Abraxas did, too, and it shot up the charts faster than our first album had. It was all these streams coming together, creating a river that just kept getting bigger and wilder. I started to see rock bands, and some jazz groups, too, getting hold of congas and timbales and making them part of their sound. Celebrities were showing up everywhere we played—stars, stars, stars. Mick Jagger saw us in London. Paul McCartney was at L’Olympia in Paris, so I quoted “The Fool on the Hill” in the middle of “Incident.” Raquel Welch was in the front row at the Hollywood Bowl. Miles and Tito Puente came to our shows in New York and hung out in the balcony.

Everybody wanted a piece of Santana—to be on TV, to be in various projects. In 1970, we played on The Tonight Show for Johnny Carson and we did The Bell Telephone Hour with Ray Charles and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. That was the same time the Rolling Stones asked us to be in Gimme Shelter, the documentary about Altamont, and we had to say no.

Abraxas was on its way to selling more than three million copies that year alone. “Black Magic Woman” was a top ten hit on pop radio, and all the underground FM rock stations were playing the album a lot. When I heard “Samba Pa Ti” on the radio for the first time, everything just froze. I was at home, looking at distant lights twinkling away, not even focusing on them, just listening. It felt good to step outside of myself and just hear the notes, which sounded like somebody else playing beautifully and with heart. At the same time I knew it was me—it was more me than anything I had recorded before. That opening part of “Samba” made me think, “Whoa. I can hear my mom talking, or Dad telling one of his stories.” It’s a story without words that can be played and understood by people no matter where they are—Greece, Poland, Turkey, China, Africa. It was actually the first time I didn’t feel uncomfortable or strange hearing myself.

That year was jammed, and Bill’s prediction was absolutely right—when the money got more serious, everything got more serious, and there were some ego things happening in the band. People started to change. Stan Marcum started to get the idea that he should be in the band, playing flute. He also called a band meeting around this time with Bill to basically call Bill on the carpet for taking too much money and to work out clearly who the band manager was. It was like he was drawing a line in the sand. Bill took charge of the meeting from the start. He was prepared—he had written down a long list of all the shows and tours and TV gigs he had gotten us and all the other things he did to support us that were beyond the call of duty—such as free rehearsal space and the idea for “Evil Ways.” It was obvious that Stan was not in Bill’s league, yet we felt we had to choose between Bill and Stan. I didn’t say anything. Bill could have just said, “Woodstock.”

Bill had done stuff for us that we didn’t even know about, not until years later. When we were negotiating our very first contract with Columbia, Bill and his lawyer looked it over, and for some reason they inserted a line of small print on the back—something to the effect that if Columbia brought our music out again on different formats, the royalty rate would stay the same as it was on the original releases. When compact discs got big in the ’80s, Santana started getting checks with lots of zeros from sales of the old albums in our catalog, and when Supernatural went worldwide in 1999, the same thing happened. It’s a gift that still keeps giving back—thank you, Bill.

By the end of 1970, Neal Schon had been hanging around for a while, jamming with us. Both Neal and I were playing Gibson Les Pauls, but we had different signatures—so that wasn’t a problem. I had a Les Paul to replace the red SG I had played at Woodstock and subsequently broken.

I liked Neal’s dexterity, and he brought a lot of fire for someone so young, yet in a humble way. We had some tunes he sounded good on, and we started thinking about where to put solos so we wouldn’t have two guitar solos in a row. When Gregg soloed I would comp something that would stimulate him, and Neal was able to do his own thing and find his way through it.

Neal’s playing next to mine made me think of bands I liked that had two guitarists and how they worked together—the Butterfield Blues Band had Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop. Fleetwood Mac had three guitar players back then—Peter Green, Jeremy Spencer, and Danny Kirwan. Eric Clapton had a new band, Derek and the Dominos, with Duane Allman on some of the tunes.

In November, Clapton came to San Francisco with the Dominos, and because Bill was the promoter he arranged a special get-together for all of us at Wally Heider Studios. We were all there with Neal, and when Eric showed up the only problem was that I was tripping and too out of it to jam. I said to myself, “You better sit this one out and just learn.” Eric had heard about us and was really gracious to come over and hang. We all had a good time, and I liked Eric—I was comfortable with him because I could tell we were coming from the same place.

The next thing we knew we were hearing that Clapton had asked Neal to join the Dominos, which made me think that if we wanted to keep Neal with us we only had one choice. It felt good to have another strong melodic voice in the band, and I wasn’t threatened by the idea—I wasn’t paranoid or too proud to have another guitarist with us. It was my decision to ask him to join us, after I spoke with the rest of the band. Neal said yes, and by December he was part of Santana.

I know a lot of people have their own perceptions about whether Santana needed another guitar player or not. I remember Miles had his own idea about it—expressed once again when we were at the CBS offices riding up the elevator one day. “Why did you do that? You don’t need him.” A few years after he said that, Miles had two guitars in his own band—Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey, and then in the ’80s he had John Scofield and Mike Stern together. I’m just saying, you know?

Besides, Miles had no way to know that we had some new tunes we were doing, such as Gene Ammons’s “Jungle Strut,” that would be on the next album and that I wanted to play with two guitar players. I asked Neal to join not because I was thinking about who played which parts or that it would free me up—it was much more about adding more flames to the band, the sound and energy we had together. The fire that Neal brought was a white, white heat.

The year 1970 ended with Columbia getting ready to release “Oye Como Va”—and by January we were preparing to go back into the studio to work on songs for the next album. We kept going ahead, playing shows, not slowing down. It was crazy energy sometimes, and we could be cocky in Santana, even before we got big.

Sometimes it was just playing tricks and pranks: one time Carabello, who was always being a goofball, poured a strawberry milk shake on top of one poor waitress’s beehive hairdo. We also learned that Chepito could be crazy—he always wore long trench coats that had lots of pockets on the inside, and he’d always be filling them up with freebie stuff and other things he’d find on the road—soap and shampoo, towels, even silverware.

One time he bought a really big suitcase and filled it up with all sorts of stupid shit. We’d say, “What are you doing, man?”

“You don’t get it? I’m the Robin Hood of Nicaragua. I’m bringing the poor people back some stuff that I got from the white gringos.”

“Okay, but toilet paper and lightbulbs?”

Sometimes people did stupid things that really got us in trouble. Once, we arrived at LAX the same week that Abraxas came out, and Chepito was carrying a box of albums with him. His coat made the metal detector go off, and they asked, “Okay, what’s in the box?” He said, “Explosives.” Bam! Airport security handcuffed him and hauled him away and really put him through the wringer. We knew this was going to take a while, so we split for the hotel, and Ron stayed behind. Security finally let Chepito go when he told them he was talking about the music being explosive—“Man, it’s the brand-new Santana album.” He really went over the line, but he never wanted to back down from his logic. “It is explosive, man.”

Things were coming at us fast, and it didn’t help that drugs were getting easier and easier to get the bigger we got—you didn’t even have to look for them; the drugs would find you. I can’t deny that drugs had a lot to do with the environment that Santana came from, but my thinking was always that none of it mattered to me as long as the music kept going at the supreme level that it needed to be on. “Don’t lose respect for that, man, because that’s what got us here,” I would say to the band.

The real problem was heroin—some members of Santana and other people around us were using, and it was starting to get in the way of the music. We were playing a lot, but we weren’t getting together and rehearsing and thinking about songs and melodies and parts, as we had just a few months before. Some people couldn’t hang with the momentum of the band. I’d wake up with cold-sweat nightmares—we’d be scheduled to play in front of fifty thousand people, and they would have been waiting for us for twenty minutes… twenty-five… half an hour, and we’re still not ready to play because some of us are just too fucked up. I kept presenting that picture to the rest of the band. “Man, I keep having this same nightmare. First it concerned me, then it worried me, and now it’s fucking pissing me off!”

They’d look at me like, “Who are you to tell us this stuff? You’re doing the same kind of thing—smoking a lot of weed and messing with LSD.” They had a point—I hadn’t really been in a state to play at Woodstock, but at least I was together enough to pray to God to please help me. I’d tell them, “Yeah, man, but I’m not incoherent. That stuff is not getting in my way.” I always felt that heroin and cocaine were more than disruptive—they were destructive. That’s the best way of putting it.

I wasn’t an angel about this. I tried heroin a few times—the first time because some of the people in the band’s crew were shooting and they invited me to try it, and it was really incredible. I tried it a second time, and it was really, really incredible. I found myself playing all night and drinking water and thinking, “Whoa, this is easy, to play like this.” It felt like worries and fears just went out the window, and you’re super relaxed and just having a good time.

The rush was immediate, and it didn’t make me throw up. I just went to the guitar, and the next thing I knew I’d been playing for so long that my fingers were black from the strings—and they didn’t hurt. Playing after shooting up was very seductive and deceiving—while you were doing it, it felt like you attained a facility to articulate on a level beyond what you had previously known. You could play up and down the neck of the guitar without doing anything wrong—you thought. But the next day you’d listen to the tape you made and realize that you were deluding yourself. Heroin will do this to you.

It was important for me to know, really know, that I never needed heroin to get into that kind of trance with my guitar. On any given day I can be playing and look down an hour later and see drool hanging from my lip down to my shirt—I’m that euphorically into it. I look at myself when that happens and go, “That’s great—that’s a badge of honor.” But I do try not to do that onstage.

The third time I was getting ready to shoot up, I was in a bathroom with a cat who couldn’t find my vein. By the grace of God, just as he found a place to inject me, the door to the medicine cabinet opened by itself, and the mirror swung right into my face. Suddenly all I could see was myself up close, and I looked like the Wolfman in one of those movies on late-night TV. I was like, “Holy shit”—it really freaked me out.

I said, “Hold on, hold on.”

“No, it’s okay—I found it.”

“No. Please take the rubber band off. Don’t put that in me. You can have mine.” He looked at me. “Really—I don’t want it.”

Something in the way the mirror opened up and the way my face looked in it told me once and for all that heroin wasn’t for me and that I would never touch it again. Thank God I wasn’t hooked yet and didn’t need to take it. I’m pretty good at listening to signals, and this one felt like more than an omen. I really got the message: heroin and cocaine are not for you.

So I knew how heroin felt and why people would do it—but by the end of 1970 I couldn’t stand watching what was happening to some of the people in the band and what it was doing to our music. There were more fights and arguments than making music—the joy of it felt like it was leaving. Being onstage in Santana was like being in a football team, but when you start throwing the ball and the same guys keep dropping it, then it begins to wear on everyone, and you can feel it coming apart. But every time I said something about it, people would deny it, and if I said anything about the drugs, they would react like I had a huge thermometer in my hand and I was going to put it in somebody’s butt. People would look at me and say, “There is nothing wrong with us; what’s wrong with you?” It was frustrating—it felt like there was no way to get through that.

On New Year’s Eve we played a festival in Hawaii and had a few days off. The morning after the concert I woke up around five thirty in the house we stayed in, right on the beach. It was still dark, but I couldn’t sleep, so I went and woke up Carabello. I said, “Michael, I need your help, man. I need you to wake up and take a walk with me.” He saw I was serious. We started walking down the beach, and he listened to me.

“You and I started this thing, man. But something has to change, because we’re not making any progress—we’re getting worse with our attitude to the music. We’re getting really arrogant and really belligerent. It’s becoming a drag now to even deal with going to the studio, and if I’m feeling that then I know it’s got to be like that for the others. This merry-go-round is not going anywhere, and we’re not creating music that I feel has the same power as what we were doing at the start.

“Look, I’m in this and with all of you—I’m part of it, but I want to change. I want us to go back to the way we started, rehearsing new songs and trying out different things. I want to bring that joy back. But if things don’t change, I might have to leave the band.

“I need your help, man. I think we need to have a meeting and bring this up and talk about it and really, really deal with it.”

Carabello and I still talk about this conversation today. He brought it up recently, reminding me that I woke him up and took him walking. “You really tried to talk to us about changing our course before we hit a brick wall or went over a cliff. You were right.”

That morning on the beach, Carabello looked at me and said, “Okay, man. Let’s take care of this.” But it was a long time before we did.