CHAPTER 12

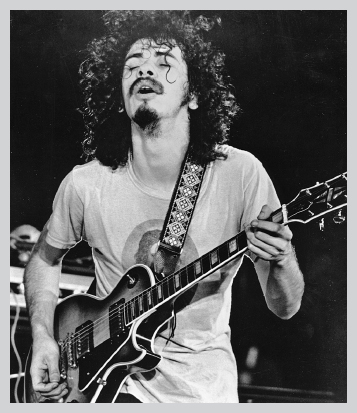

Me in my Jesus T-shirt, Ghana, March 6, 1971.

I want to talk about Africa. I’ve only been there a few times, but each time I’ve gone the first thing my whole body is thirsty for is the rhythms—to hear the music and see the dancers. It’s about connections between us and where we came from. To this day, African music is my number one hunger. I can never get enough of the rhythms, the melodies, the second melodies, the colors, the way the music can suddenly change my mood from light and joyful to somber. If people ask me, I tell them that we play 99.9 percent African music. That’s what Santana does.

Ralph J. Gleason reviewed our album Santana III in Rolling Stone —everything he said was right on. He said that the rhythms we use should be put under a microscope so people can tell how each one leads back to Africa. In my mind, I can see a map that shows how we can trace all the rhythms we have over here in America back through Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean and Latin America, all the way to different parts of Africa. What was the rumba before it was a rumba? The danzón? The bossa nova? The bolero?

Maybe music doesn’t always fit into maps so well, but I’d like to see someone try. Some places need to be bigger on the map than they actually are because they’re more important than people know—Cuba; Cape Verde. It’s crazy—Cape Verde gave birth to music in Mexico and all over South America, especially Brazil. When you hear a certain kind of romance in music—the bolero, the danzón, the slow cha-cha—it all came from that one little island. You would have to bring the focus in on Colombia, too, with those bad cumbias that Charles Mingus loved to play. Then you have Texas, Mississippi, and Memphis shuffles, and all those street rhythms from New Orleans. It would be fascinating to see where the arrows point.

I wish there was a school here that just taught one thing—how to have some humility and recognize that Africa is important and necessary to the world—and not just because of its music, either. When it comes to African music, I got nothing but time to learn. I think I’ve surprised a few African bands because I was able to hang with the music—there’s too much groove not to!

One more thing about Africa: one of the greatest compliments I ever received was not on an awards show but from Mory Kanté. He’s a great singer and guitar player from Mali. I love, love, love his music. He was part of the “Dance to the Beat of My Drums” concert we did with Claude Nobs in Montreux. I was there in my tuning room, and an African gentleman came in and said he was Mory’s representative and that Mory apologized because he did not speak English, but he had a message to tell me. He told me the message in their language, then he translated: “Mory wants to tell you that your belly is full, but you’re hungry to feed the people.”

Then the man bowed and walked out.

Wow. It sounded like a great compliment. I’ll take it.

If music is from many places it’s also from one place, and Santana could not have happened without San Francisco. If you needed to meet a good bass player, somebody always knew somebody else, or maybe you’d hear about a new piano player or drummer or group you had to check out. My own brother Jorge was coming up with his band, the Malibus, and getting a reputation on guitar—then they changed their name to Malo and got together their own mix of rock and Latin rhythms and Spanish lyrics. A few years later some musicians from Malo would come to Santana as well as certain players from Tower of Power, the great horn band from Oakland. Even today I look at bands close to home for people who might come into Santana.

That’s how things flowed in San Francisco. Santana was never exclusive—like many bands, we played and jammed and did sessions with each other and found new ideas and people to go on the road with. Just as Neal eased into the band, we were open to thinking about playing and recording with other musicians. We were open to having other people sing lead besides Gregg, too—as we did on “Oye Como Va.”

You get all that on our third album. We started the sessions for Santana III at the beginning of 1971. Rico Reyes came back to sing on another song in Spanish, “Guajira,” and Mario Ochoa played piano on it. We had the Tower of Power horns on “Everybody’s Everything,” which became the first single from the album later that year. We opened the door and invited Luis Gasca to play on “Para Los Rumberos,” another Tito Puente song we wanted to cover. We made it our “Dance to the Music”—we sang the names of Carabello, Chepito, and me before playing our parts. Greg Errico from Sly’s band and Linda Tillery from the Loading Zone played percussion on some songs, and we had Coke Escovedo playing percussion all over the album.

Coke came in and added so much to the sessions from the start that we had to give him credit for the inspiration he brought to that album. Coke’s roots are Mexican, and he had played with Cal Tjader before he played with us. He’s one of the famous Escovedo brothers—the whole family makes music. His brother Pete also plays percussion and is Sheila E.’s father. The brothers had a Latin jazz group together that played around the city, and in ’72 they formed Azteca, the Latin rock-jazz group that many musicians got started in. Coke helped write “No One to Depend On,” the second single from Santana III, and he started touring with us.

The challenge of the third album was finding new tunes and new ideas to fit with our sound. We put the pressure on ourselves because, for a little bit longer, we were still at a point where we could be a unit. We would be rehearsing, and suddenly someone would say, “Hey, I have an idea” and play it, or someone would want to start playing a Latin tune or a B. B. King riff he had been hearing, and we’d work out our own interpretation of it right on the spot. The tune “Batuka” came from a musical arrangement that Zubin Mehta sent to us to play with the Los Angeles Philharmonic on The Bell Telephone Hour on TV. The piece was written by Leonard Bernstein as “Batukada,” and it’s a long score, and we were looking at it like monkeys trying to figure out schematics for a computer! “What the fuck is this?” But we liked the name, so we shortened it to “Batuka” and said, “Let’s just make up our own shit, man.” That’s how that tune came about—it was just based on the name of the score Mehta gave us.

That’s also how we were able to come up with “Toussaint L’Ouverture” in the studio. It was one of the last things we did with Albert Gianquinto. “Everybody’s Everything” was based on a 1966 song called “Karate” by the R & B vocal group the Emperors—it had a great hook that I couldn’t get out of my head. I had heard it once on the radio, then a few years later I was in Tower Records, where I always did some research, buying 45s of old hits from the ’50s and ’60s. I found it still on sale, and the staff played it for me, and I was thinking, “Damn—this is like black hillbilly, hoedown kind of music,” and I loved it.

The song was about a new kind of dance, but that wasn’t what Santana was about, so I made the thing happen with the lawyers, who called the two guys who wrote the song—Milton Brown and Tyrone Moss—and got the okay for us to come up with our own words. Neal played the solo, and we kept the “Yeah, I’d do it” from the original.

I looked through my Rolodex of music that I loved and brought in “Jungle Strut” by Gene Ammons. I played it for the band, and they said, “Yeah, that sounds like Santana. We can do that.” We wrote “Everything’s Coming Our Way” together—it was my way of sneaking some Curtis Mayfield into our music. David was getting into Latin and Afro-Caribbean music more and more—he worked out some ideas with Chepito and Rico Reyes and came up with “Guajira.”

We normally did one song a day in the studio, but because of our touring in ’71 the sessions for Santana III stretched over more time than any other Santana album—we started in January and were still recording in July. We would record in San Francisco, hit the road for a while, and on the way back home go into a New York studio with Eddie Kramer. We were crossing those time zones—both in the United States and overseas. The road could be rough if you let it get that way. Chepito could burn like a two-ended candle—but then he had an aneurysm and got so frail he couldn’t play for a while. We asked Willie Bobo to come in and take over timbales, and he did.

In March we got on a plane in New Jersey that took us farther from home than we ever thought we’d go. We received a phone call about going to Ghana to help celebrate the country’s anniversary—they wanted Santana to play in a festival with Ike & Tina Turner, the Staple Singers, the Voices of East Harlem, Les McCann, Eddie Harris, Wilson Pickett, and Roberta Flack. We had a choice: we could go to Ghana or stay home and see Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles at the Fillmore West—they were recording a live album. That was tough. But we said, “Let’s go to Africa.”

Next thing I knew I was on a flight sandwiched between Roberta Flack and Mavis Staples, and they were singing “Young, Gifted, and Black”—I got it in stereo. I said, “Whoa. This is going to be fun.” Next to us was Wilson Pickett’s horn section.

The whole plane started partying as soon as we took off. There was no one but musicians on board—everyone started smoking weed and doing coke. Willie Bobo turned out to be like a running comedy act, an instigator of practical jokes and funny stories. He knew how to poke you to see if you had the wisdom to laugh at yourself, although a lot of people may not have been ready for it. You’d either get pissed off or you’d laugh. It seemed that half the material he could have created for Bill Cosby. Willie had that kind of presentation. He and I got really close at that time.

It was the longest flight I’d ever been on—more than twelve hours. When we landed the whole airport looked like a tsunami of Africans—they were all there to greet us, all colors, sizes, and shapes. Some were so black they were almost iridescent blue. It was beautiful—they came right up to the plane. We walked down the stairs, and the crowd started parting like the Red Sea in front of Moses, and suddenly there was a line of local people representing Ghana’s twelve nations coming to meet us. Each nation had its own dancing style and costumes, some decorated with big buffalo horns and seashells. Each group greeted us one at a time, then the mayor of Accra and his party got their turn.

The whole scene was incredible to see and hear first thing after landing. Then we saw a witch doctor kind of guy—he was wearing animal skins and shaking a big gourd that was as big and round as a basketball. He made it rattle like a Buddy Rich roll. It was obvious by the way he took center stage that he commanded a lot of respect. Even the mayor’s people got out of his way, and the people who were filming the trip and concert loved him. We were like, “Who is this guy?”

Willie decided he would show off—he had an amulet that he wore, and he started saying that his voodoo was more powerful, that he had his own thing going on. Back then I figured we all had our own way of dealing with the invisible realm. I just wasn’t flaunting mine. But that holy man fascinated us and scared us at the same time. I could tell right away that he was a sorcerer and had a way of dealing with the invisible realm—he could reach the spirits. And that wouldn’t be the last time we saw him.

We got through customs and went straight to the hotel to get ready for a big dinner that the president was hosting. Before we started eating everyone was asked to rise, and a group of men and women sang Ghana’s national anthem, which was in a kind of call-and-response form. Suddenly I recognized it—it sounded very close to “Afro Blue.” I couldn’t believe it. If this wasn’t where Mongo Santamaría got the song, then they were close cousins, man. Both were coming from the same place.

We were there for almost a week, and there was a lot of looking and learning going on. The next day Carabello ate or drank something and came down with dysentery, which kept him in the hotel, close to the bathroom. Shrieve and I went into town to the market to just look around, and our taxi got stuck in traffic—bumper to bumper, all the windows down. I had brought a cassette player along and was listening to some Aretha Franklin on my headphones. A woman who was walking by stopped right next to the car and was staring at me like I had just stepped out of a flying saucer. I took the headphones off and showed her how to put them on her head. She did, and her eyes got real wide, and she smiled a huge smile. It was connection with penetration—it was like family there.

Workers were still constructing the stage when we got there, so we had to wait for them to finish. At night we were on our own and would all hang out in the only place we could—in the lobby lounge of the Holiday Inn. We ate there, drank there. We laughed when Willie Bobo was holding forth, making everybody hoot. One night he started picking on Wilson Pickett—“Hey, Wilson Pickle. Wilson Pickle.” Pickett could be a tough dude. He was serious, like Albert King—he didn’t take any mess. But Willie kept at it. “Man, let me show you what you’re going to be doing in your show.” He got down on one knee and put his coat on like it was a cape. “Just like James Brown, but it ain’t gonna work, because here in Africa, James Brown is number one. Sorry to tell you.”

I couldn’t believe it—I got myself over to the other side of the lobby as fast as I could, away from the intensity. I think we were all getting itchy to get out more, and at the same time I remember wishing some of us had been more understanding and respectful of the people and their culture. I remember Pickett would say that Africans needed to use more deodorant, and Willie was ragging on the holy man we met at the airport—he was really a charlatan, a guy who had people convinced he had some kind of power. I also remember hoping that the witch doctor didn’t pick up on any of this—just in case.

The next night in the lobby bar I heard an African guy in a suit and tie talking about how we were there just to steal their shit and exploit their music. He said it just loudly enough for me to hear him. I walked up to him and said, “Excuse me.” Then I handed him my guitar and said, “Here, man, play me something.”

He said, “What? I don’t play the guitar; I’m a lawyer.”

“Then it’s not your fuckin’ music—it’s only yours when you play it.” I could be cocky, too, and I liked to make my point. He grabbed his drink and gave me my guitar back.

I went back down the next day—it was the same place, the same people, like they hadn’t moved from the night before. Later that afternoon, someone came up to me in the lobby—“Mr. Santana? Mr. Pickett wants to see you in his room.”

“Uh, Okay.”

I went upstairs, knocked on the door. A young lady opened it. I heard a voice from inside go, “Who is it?”

“I think it’s Carlos Santana.”

I went inside, and Pickett and Ike Turner were doing coke. “Come on in, man.”

“How you guys doing? What’s going on?”

Pickett looked me up and down. “So you’re the magnificent one, huh? You’re the Santana? You’re that guy?” I knew from back in my Tijuana days where this was going—I didn’t want any of that. “I heard that you wanted to talk to me, so I’m here, but before we do that I just want to let you know that I have all your albums. I play all your songs and love them. ‘In the Midnight Hour,’ ‘Land of 1000 Dances,’ ‘Mustang Sally,’ ‘Funky Broadway,’ ‘Ninety-Nine and a Half (Won’t Do)’…” I kept going down the list, and it was true—I learned all of them. “I love you, man.”

Wilson looked at Ike. Ike, to his credit, just shook his head, like, “It’s cool. Carlos is okay.” I politely got out of the room.

It wasn’t the first or last time that happened—meeting a musician I love who was mistrusting or not happy with praise. But I have to say it very rarely happens—I think over the years I can count on one hand the number of those kinds of meetings.

I met Eddie Harris in Ghana on that same trip and asked if we could play together on one of his songs. “Hey, Eddie—you want to jam? Let’s do ‘Listen Here’ or ‘Cold Duck Time.’” He shook his head. “No, Santana, you’re not going to beat me with my own shit. That ain’t going to happen.” I wasn’t looking at it like that and tried to explain. “Man, I just love your music.”

It happened another time just a few weeks after we got back from Africa, when we shared the bill at the Fillmore East with Rahsaan Roland Kirk. The night Miles was there and flicked my ear, I knocked on the door to Rahsaan’s dressing room, something I rarely did. It opened, and I remember it was almost pitch-black in there. Rahsaan and some of the guys in his band were in the room. “Mr. Kirk, my name is Carlos Santana, and I’m just here to thank you from the center of my heart for bringing so much joy in your music, man. I’ve listened to Volunteered Slavery and The Inflated Tear…” As I had with Wilson Pickett, I started naming the songs I loved, then I waited. All of a sudden they all started laughing like hyenas, just laughing and laughing. I quietly found the doorknob, opened it, and walked out. I told myself, “Okay. I’ll never do that again.”

Another thing I won’t do is mess with any black magic. We ran into that holy man again walking near our hotel in Ghana, and a chicken crossed his path. He stopped and looked at it in a weird way, and pow! The chicken suddenly fell over dead, even though it had just been looking fine and healthy. Everyone backed up and gave the guy room. We got back to the hotel, and at the restaurant all the guys in Pickett’s band wanted to tell him the story. “Pickett, man, you’re not going to believe what this voodoo guy did. Man, it was freaky!” Pickett kept saying, “No, no. I don’t want to know. Don’t tell me, don’t tell me.” But they wouldn’t stop—they were like kids coming back home and needing to tell their parents about something that happened at school. They told Pickett about the chicken, and he just shook his head. “I told you not to tell me this shit, man. Now I’m going to have nightmares.” Meanwhile Willie Bobo was cracking up.

The last day before the concert in Ghana, the organizers found something for us to do. They invited us to the Cape Coast Castle, which was a place where Africans were held before they were put on the slave ships that would take them to various parts of America. It was basically an old brick fort painted white, right next to the ocean, with cannons in front. We had a tour guide explain what had happened there. He showed us the “gate of no return,” which the slaves went through as they walked on African ground for the last time. He took us down into a horrible, hellish basement where the slaves were stuck waiting for the ships. All of us got really quiet—you could still feel the intensity from all the souls that had been crammed in there.

The wind picked up on cue and started making a whistling, lonely sound as it blew through the cracks and crevices in that old fort. All of us got chicken skin—it was like the sound of souls howling in pain and horror. Woooohaaauuuiiiiiii! Tina Turner heard it, and her knees got weak and she started crying and people had to carry her back to the bus. The wind kept blowing harder, and the whole thing got more and more creepy. Thinking about it now still gives me chills.

Willie didn’t come with us to the castle because he wasn’t feeling right. When we got back to the hotel he was really sick—sweating with a fever and vomiting. It was the same thing that Carabello had during most of the trip, but worse. He had a serious fever, and it wouldn’t go down. We all took turns staying with him and putting cold towels on him throughout the night. Around midnight, a local doctor in a suit and tie came by while I was watching him and started looking at him.

The doctor said it was dysentery, and I couldn’t help thinking about that holy man and all the things Willie had been saying and wondering—well, we all felt that way, suspicious and not sure what to believe. Just then somebody knocked on the door, the doctor got up to answer it, and sure enough, there he was—the holy man, stopping by to look at Willie. The doctor let him in, but I got up and blocked his way. Our eyes were locked on each other, and we had an inner conversation—I spoke to him inwardly.

“Man, I know you got the power, and I know you did this to him.” Then I pointed to my T-shirt, which had a picture of Jesus on it. I kept talking to the holy man in my mind. “I respect and honor the beliefs that people have all over the world, as I do yours—but can you get through Jesus? You may be able to go through me, but you also got to go through him, because I am not only with him but I also belong to him.”

You have to understand that I respect and honor Jesus Christ—he was a remarkable historic figure who stood up to authority and believed in common people and the power of his message—and he was killed for it, pure and simple. The thing about Jesus that gets lost, I believe, is that he was a man—that he was born and that he had to grow up to become who he was. He was a man, and he must have been a very attractive one at that, because he had charisma and people loved him. Women loved him. It’s strange that the Bible says nothing about when he left home as a teenager and came back later. Where was he between the ages of thirteen and thirty? I believe the man went around the world—to Greece and to India. He got around, and he did things. He had to so he could learn to feel what it’s like to live, how it is to eat well and be loved but also to be hungry and scorned. To feel the sensation of what it is to be a man and also hold divine mysticism.

There’s a scene in Franco Zeffirelli’s TV miniseries Jesus of Nazareth that’s one of my favorites: Jesus walks into a temple just when the rabbi is about to open the holy scriptures and read from them, but Jesus politely asks the rabbi to move over. He does, then Jesus grasps the open scrolls and closes them, saying, “Today before your eyes the prophecy is fulfilled” and “The kingdom of heaven is upon you.”

The people in the temple all get twisted and think it’s blasphemy, but they don’t understand his message: we can stop suffering—the divinity is already here, in each one of us, which ultimately is not what the church wants us to hear because they want the control and the message to come through them. From his aerial view of the situation, whether he speaks through Jesus or Muhammad or Buddha or Krishna—or whether he communicates directly to each of us—God can reach any part of anyone and say what we need to hear. No one should have a monopoly on that connection; no one can say with certainty, “You have to go through me to get to him.” That sounds like a pimp to me.

I have a problem when that message gets twisted so that certain people are in a position to control and manipulate others, which is what religion has done for centuries, without coming to the aid of people who need help—when religion lets people suffer because of its dogma and traditions.

There’s something else I like about that scene: Jesus was one of those guys whose duty it was to stand in the middle of a crowd and say, “Hey! The world is not flat,” and that takes a lot of courage. It’s how I feel about someone like Ornette Coleman, who came to New York from out of town with a different kind of music when everybody else was doing a more established kind of jazz, whatever that was. I have a lot of respect for people who not only have the clarity to see but are also not afraid to step up and speak out.

If Jesus were around today in the flesh there wouldn’t be a Christmas. That’s about business, and religion is an organized institution like the Bank of America, and it has a lot more money than the Bank of America. There’s a saying that I love: “You got to give up the cross, man. Get down from there—we need the wood!”

Jesus was never about rules and requirements. He had a Christ consciousness, and he was not interested in dividing the world into believers and nonbelievers and saints and sinners and making everyone feel guilty about being born into sin and telling them they need to suffer because of that.

It wasn’t a “my God versus your god” thing when I stood up to that shaman in Ghana. I was just facing my fear and calling on the power of love, which is the most supreme force of all—love and forgiveness, allowance and willingness. With just those few things, miracles can happen and human consciousness can be advanced and fear can be eradicated.

The holy man glared at me. I could see he understood what I was thinking. He looked at my eyes, then at my T-shirt, then he turned to the doctor, and they nodded at each other. It almost seemed to me like they had a thing going—one of them would get people sick and the other collected when he brought the medicine. Then that holy man walked out. Nothing happened to me—I didn’t catch dysentery.

Check out Soul to Soul, the movie of the concert—Willie was able to play the next day, but you can see he was very listless. You can also see the crew getting fascinated with that holy man, turning the cameras on him whenever they could. Who knows? Maybe he worked some voodoo on them, too.

I remember Ike and Tina went on first—they had the theme song for the concert, “Soul to Soul.” Wilson Pickett was the top headliner, and I think we played pretty well. What was peculiar was that the crowd didn’t know when to clap. We would finish playing a tune, then… nothing. You could still feel that they were thinking it was really cool, that they really liked us, but I think the long songs and the various sections confused them, as they did with my father. They were learning through all the music, though, because they applauded when we finished the set and were clapping and dancing by the time Pickett played.

The Voices of East Harlem, with Dougie Rauch still on bass, played that night, too, and they impressed me more than the first time I heard them, in Tanglewood. They had a great song called “Right On Be Free” that sometimes I will play with Santana even now, more than forty years later. I like music with a message like that, music that I call brutally positive—such as Curtis Mayfield’s songs or Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” or the Four Tops’ “A Simple Game”—because people need a constant jolt of “Kumbaya” that’s not goody-goody. There’s a lot of African music like that, too—I love Fela Kuti and his son Seun, who does a song that goes: “Don’t bring that shit to me… don’t bring bullshit to Africa.” I love songs that say, “I’m going to take all those words and tell you straight about what’s goin’ on and whoop your fears with it.”

After I got back from Africa, that trip stayed with me for a long, long time. I brought albums home with me and started to collect more wherever I could find them. I said, “Thank God for Tower Records” when they made a separate section for African music. I wanted to have one room in my home just for African music because I wanted to learn how to play it. It was rough trying to find the records at first, then starting in the ’80s, when I would be in Paris you could see me making a beeline for the African section in those big music stores on the Champs-Élysées. I’d get a basket and just start grabbing.

Chepito recovered from his aneurysm, and he and Coke Escovedo joined us after we got back from Africa. We toured from the Bay Area to New York and then went to Europe, where we played the Montreux Jazz Festival again in April. We returned to the United States and toured, sometimes with Rico Reyes or Victor Pantoja, who played congas on the first Chico Hamilton record I ever heard. And in July, we finally finished recording for our third album—Santana III.

We were doing a lot as a band, but things were not getting better inside the band. I think the first real cracks in Santana, the cracks that started forming the winter before, had started to show in terms of our musical tastes. At first the differences in what we were listening to helped us develop as a band: we shared it all, and it held us together. But by the time we were in the middle of recording our third album, our differences had us wanting to grow in our own separate directions. Gregg and Neal wanted to do the Journey thing—more of their kind of rock sound. David Brown was getting deep into Latin dance music, and Chepito was already there, listening to Tito Puente and Ray Barretto. I was pregnant with John Coltrane and Miles—Shrieve was, too. I was also getting into Weather Report, which had musicians who played with Miles on Bitches Brew—Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter were the nucleus of that new group.

You could really sense those differences after our shows, when we’d be hanging in the hotel. Shrieve and I would get together to listen to our favorite music in his room or mine, turning each other on to different records that had just come out. It could be jazz or soul or whatever. Girls would come by, looking to get high and party, and they’d get bored when the two of us would be going, “Check out this groove!” or “You gotta hear this solo.” They’d move on to Chepito’s room or David’s.

I’m not judging one thing against another—there’s time for everything. But it wasn’t just music—by 1971 differences were also showing up in the priorities of some people in the band. The rock-and-roll lifestyle was taking over; it wasn’t just the women or the cars or the cocaine and other excesses, it was also the attitude. We used to say that we were from the streets and we were real—we’d look at other bands that were making it and judge how they acted. “We’re never going to be assholes like that,” we’d say. But I saw how some people in the band were acting, and I was thinking to myself, “It’s easy to see why a lot of bands fail—they OD on themselves.”

I thought Santana was becoming a walking contradiction. The soul wanted one thing, but the body was too busy doing something else, and we were trying to be something we weren’t anymore. Everything that Bill Graham said would happen was coming true—our heads were getting so big it was starting to feel like there wasn’t enough room for everyone. I think we were all equally guilty of this.

For me the worst thing still was that we weren’t practicing or working on new music, and I was hungry for that. I’d have to work at getting us together to play. I’d say, “There’s dust on those platinum albums, man. Our music is starting to get rusty. We need to get together, and it shouldn’t be like I’m saying we have to go to the dentist and deal with an abscess. We should get together—I’ll rejoice with your songs, and you’ll rejoice with mine, as we did on the first two albums.”

Being a collective made us possible in many ways—it’s what we were. But there was basically no discipline, and nobody but Shrieve wanted to hear that we might be making incorrect choices. We were very, very young—even our manager was young. He was supposed to be looking out for us, but he was participating in many of those excesses. He was using and helping to supply the band, and he still wanted to be in the band.

Some people in the band were angry at me because I was not happy most of the time. It’s true: I probably wasn’t a pleasant guy to be around, because I was complaining about this and that. I was feeling myself in conflict with so much money and so much excess, and the spiritual side of me was being crushed.

I was starting to lean more deeply in a spiritual direction at this time. It started with a few books. The only thing I had read when I was a kid was comic books—Amazing Stories; Stan Lee’s Iron Man and Spider-Man. At the start of Santana I was already moving over to books about Eastern philosophy. In the Bay Area it was in the air—everybody was reading The Urantia Book and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi and Swami Muktananda’s memoir. I read all of them, too.

There were yogis who came through San Francisco, and they would speak to whoever came to hear them—followers and friends who were curious. Sometimes I heard that John Handy or Charles Lloyd might show up, which was one more reason to go. I got to know the names of various gurus, including Krishnamurti and a young, pudgy guy called Maharaj Ji. There was also Swami Satchidananda, whom Alice Coltrane was into. They’d sell books after they spoke, and I would pick them up.

Everyone had heard about the Beatles and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the guru they followed for a while, and some people saw him as a trickster. I began to understand that these gurus were not charlatans but very wise men who could help people see their own luminosity—the divine light each person has inside, which enables us to lessen fear and guilt and ego. I learned new words for these ideas—words like awakening. That was really the job these teachers were doing: awakening people to a higher consciousness.

The next thing I knew my molecular chemistry began to change just by being curious and considering the metaphysical questions these gurus would talk about. It was a new language I was learning. I started asking questions like, “How can I evolve and not make the mistakes that everybody around me is making? How can I develop a bona fide, tangible spiritual discipline—with or without a guru? How can I connect this to my rock-and-roll lifestyle and the music I’m making?”

I was starting to get an inner urge to read more books and listen to music that resonated on the same frequency. I started to put aside Jimi’s music and even Miles’s for a while. I looked for the resonance I was getting from these gurus and found it when I was listening to Mahalia Jackson or to Martin Luther King’s speeches—just his words and his tone and intention. John McLaughlin came out then with his new group, the Mahavishnu Orchestra—I played that first album over and over and felt their intention.

I also played lots and lots of Coltrane. He stayed on my turntable for a long time. I was learning, trying to comprehend the language of ascension. “The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost” was the door for me. That was not easy, because the first ten times you listen to it you can’t even find 1—the downbeat. It’s all 1, and the only close resemblance to a melody in there is “Frère Jacques.”

I could play guitar and hang with the modal music Coltrane was doing later, around the time of A Love Supreme, but Shrieve helped me get a feel for Coltrane’s earlier stuff—and that of Miles and other jazz guys—because the idea of thirty-two-bar songs and AABA parts was all new to me. He would say, “Here’s the bridge” and “This is a tag.” “See how they modulated to another key?” or “Hear how the first sixteen bars are played two-beat and then the bridge is in 4/4 to get a swing feel?” Shrieve started in a high school jazz band, so he had some training and could be a guide.

As intense as Coltrane’s music is, that was becoming my peace of mind. I’d play Coltrane or Mahavishnu, and I could be by myself. Cocaine and partying and all that fast living do not go well with A Love Supreme and The Inner Mounting Flame—that music was like daylight to vampires. Sometimes I’d play Coltrane for my inner peace, but to be honest sometimes I’d do it to get people who were hanging out too long at my place to leave. It would work every time—whoosh!

I know Coltrane was about peace and nonviolence, as Martin Luther King was—you could hear that in his music. But the intensity that I saw turning some people off was coming from the supreme intention there—the kind of intention I connected with in the Black Panthers across the bay in Oakland. We had gotten to know about them through David and Gianquinto, who was the first white Black Panther I knew. We had learned about the programs they established to help their community, like providing lunch for schoolkids. The government didn’t see it that way—they were coming down hard on the Panthers. By the time we played for them they were on the run—Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale were in jail, awaiting trial, and Eldridge Cleaver was in exile in Africa.

Some San Francisco groups, such as the Grateful Dead, did benefits to raise money for the Black Panthers so they could fight their legal battles. I remember we did two concerts for them, and I got to see how scary things were up close. We showed up in a limousine at the Berkeley Community Theatre, got out, and the first thing that happened was that security guys in black berets and black jackets asked us to stop and assume the position—“We need to frisk you.”

I said, “Uh, okay, but you know we’re playing for you.”

“We know that, and we thank you, man, but up against the wall. We still have to do this.”

Later on I understood that they had many infiltrators and people in their own organization spying on them. They didn’t trust anyone. They had to protect themselves. They were living as if every second could be their last. I could feel that, and that impressed me. I remember talking with one of the Panthers. He pushed his face close to mine, saying, “I got one question for you, man. Are you fucking ready to die right now?” He was talking about what it meant to be in the Panthers back then. “Are you ready to die right now for what you believe in? Because otherwise get the fuck out of here; if you join the Panthers you got to be ready to die right now.” I kept my mouth shut. It was scary. I was like, “Damn. This is not the Boy Scouts.” It was brutal then, and that was their level of commitment.

I know seeing that kind of supreme intention had an effect on me—it felt like it was time to make decisions. Not long after that it was clear to everyone that David was not doing well—his heroin use was showing, and his playing and the music were starting to suffer. Sometimes he’d take too much and would be nodding out and not capable of presenting the music the way it was meant to be. He couldn’t hang on the bandstand, as jazz musicians say. He was too buzzed to be open to any discussion or accept any offer of help.

Drugs had taken Jimi the year before, then Jim Morrison died that summer in Paris. In 1971 many people were getting scared—some of us were feeling that everything we had been building was falling apart. At the end of that summer, it felt like some of Santana was on the same route. Just a few months later, they’d find Janis with a needle in her, and she’d be gone, too.

I felt I had to put a stop to anything that had to do with cocaine or heroin in the band. I didn’t have any problem with marijuana and LSD, but the harder stuff had to go. It was also a matter of who was hanging around with us: dope dealers, pimps—some real San Quentin material. I had the radar for that from Tijuana, and it had gone on long enough—these people were just bad news. It was getting dangerous, and it was making us look bad.

This was when I really started to feel that it meant something that my name was also the band’s name—that started to be my explanation of why I cared so much about so many things. Why I couldn’t chill about people showing up late, or showing up in no condition to play.

“I told you why,” I would say. “This is about the music, not me. But this thing happens to have my name, and since it does I have a responsibility.”

“We just called it that because we didn’t know what else to call it. But it’s not your band,” some people said.

I would think, “Well, not yet.”

I made the decision to fire David. It wasn’t like I fired him directly, but really I did it by saying I wouldn’t play with him anymore. This was the biggest step I had made toward taking charge. I think everyone understood that it had to be that way. But we weren’t getting rid of him—it was more like we were giving David a chance to get straight, because he came back to Santana just a few years later.

We had dates to play, so we replaced David with Tom Rutley, an acoustic bass player Shrieve had worked with in a big band in college. I liked Tom—he was a big, huggy-bear kind of guy, and he had a low, low voice that I could barely understand and a great upright bass tone. He recorded some tracks with us on Caravanserai. He was only with us for a short time before Dougie Rauch took over, but Tom helped us at just the right time—when Shrieve and I were trying to navigate jazz music and imagine we could actually play with people like Joe Farrell and Wayne Shorter.

David might have been gone, and we had a bass player, but many things were still wrong—the drugs and lowlifes and hang-arounders were still getting in the way of the music. It had gotten to the point where people would wake up in the morning still drunk and fucked up from the night before, still totally buzzed on cocaine. Then they’d do more cocaine to wake up, so then they’d be tired and wired, and I was the one who kept putting my foot down. “They” were mainly Stan and Carabello.

Sometime in September, before another tour across the country, I opened my mouth, and there was an argument, and by the end of it I said, “I’m not going unless we get rid of Stan Marcum and Carabello, because they’re supplying the band with the heavy stuff and we sound like shit. We’re not practicing, and it’s embarrassing. Either those guys are out or I’m out.” I had to do what I had to do.

Stan and Carabello were in the room and I said this in front of them. They laughed and said I couldn’t do that. “We leave on Monday, man. If you don’t show up, then you’re not in the band.” And that’s exactly what happened. It felt horrible. It felt really, really horrible to be part of a band that had just left on tour without me. But that was it—there was no official separation announcement, no press release, and no legal agreement. Everyone left, and I stayed behind, licking my wounds.

My consolation for the next few weeks was going to various jazz clubs around San Francisco and hanging out, playing with guys like George Cables at Basin Street West. I had gotten tight with George when we both played on Luis Gasca’s album For Those Who Chant that summer. He was playing in Joe Henderson’s group, with Eddie Marshall on drums, and they told me to come down and sit in with them.

I was also hanging with Dougie Rauch, who had moved to San Francisco and was playing at the Matador with Gábor Szabó and Tom Coster on piano and the drummer Spider Webb. This was when Gábor and I got tight—we’d get together and play, then we’d talk and listen to music. I was just breaking up with Linda after almost four years together. He would come over to the house, and he’d feel uncomfortable because of the arguments and the vibe. After I got back with Santana a few weeks later, Linda left, Gábor moved in, and we started hanging out with a group of chicks that included Mimi Sanchez, who was a hostess at the Matador and was an incredibly beautiful, very strong woman.

Mimi is the lady on the cover of Caramba!, the album by the great jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan, and she’s the same Mimi who later married Carabello. I want to mention her—and Linda and Deborah and other women who have been in my life. There are people who are strong, independent forces in the lives of many musicians—there have to be. They help unfold us in a way that makes sense with all the craziness that can go on. They help us to not be afraid of ourselves and to learn to deal with brutal confrontations that seem so important but that really didn’t mean anything. For many of us, these people are our teachers. They nurture us and keep things together when we’re out on the road.

Mimi and my first wife, Deborah, were friends. In the ’80s Carabello and I were also friends again, and when Mimi came down with terminal cancer, Deborah threw a party for her and her family. I remember I didn’t recognize her because of her illness. Mimi had one request—that I play “Samba Pa Ti” for her. Such an outpouring of love came to her that day from her family and from Deborah’s divine giving—she washed Mimi’s feet. There was a reason Deborah and I had thirty-four years together.

Gábor and I stayed close, even after I got back with Santana. I remember so many things about him—he never talked about his time with Chico Hamilton or listened to Chico’s music. I’m not sure why. But I could tell he was thinking about a different sound when we got together—something he was working on with Bobby Womack that he later called “Breezin,’” which George Benson made famous.

One time Gábor invited me to come and sit in with him in the studio—he’d brought in another amplifier for me. “Oh, man, thank you,” I said. We ended up just hanging out, then Gábor wanted to go for a walk. We stepped outside on Broadway in San Francisco, a funky area of town. At one point he stopped, turned, and said, “Carlos, I heard that Santana is starting to have some problems. If you ever want to start a band together, you and I, let me know.”

I was like, “Really? That would be a great honor, Gábor, but what the hell do you need me for?”

One thing I think people have to know about Gábor is that even before Wes Montgomery was putting a jazz thing on rock and pop tunes, Gábor was really the first jazz guitarist to say it was okay to blatantly borrow songs by the Beatles and the Mamas and the Papas and other radio stars and record them in a jazz style, with his own thing. Later other jazz people did that, and no one could help noticing: “Hey, this idea is selling a lot!”

I was honored that Gábor wanted to build a group with me, and I did think about it, but I think he saw me as a freelance musician when really I was still part of a band. I was part of Santana, and I felt connected to Gregg and Shrieve and Carabello, even with the drugs. Later on I developed the kind of perspective that made it easier for me to do collaborations and play with other bands and still be completely in Santana.

Three weeks after Santana left for the road (minus this Santana), the phone rang. It was Neal. The band was going through the East Coast and was at the Felt Forum in New York. “Hey, man, I don’t want to say this, because it’s probably bad for your ego, but the audiences are screaming and booing—they want to hear you. They know you’re Santana. Come on—why don’t you get on the next plane?” I wasn’t changing my mind. “No. Not unless you put Carabello and Stan on the next plane home. Then I’ll be there.”

I heard later that when the band made up its mind to get me back and send Carabello and Stan home, the two of them went around to everyone’s room, letting people know how upset and hurt they were. I got on a plane and flew to New York to meet the band at their hotel. It was really awkward, because when I got there, Stan and Carabello were right there in the lobby, looking daggers at me. Carabello said, “Okay, man, you got your fuckin’ way. This is what you wanted, right?” I didn’t take the bait—I just looked at him and said, “What I wanted is the band to be thriving.”

The feeling right away was that this was going to be a new chapter for Santana. It wasn’t just that we had to find a new conguero; we also needed to do that while we were thousands of miles from the musicians we knew best. So one night in New York City we decided to put it out into the world, and we asked if there was a conga player in the audience. That’s how we found Mingo Lewis. He was a street musician with a lot of energy. We put out the request from the stage—I was probably the one who did it—and the next thing we knew this cat showed up and sounded good with us. He knew almost all the parts for our songs, so we asked him to join the band right there and then.

During those first few shows there was definitely a division, or the feeling of a divide, in the band. Half the members wanted to beat me up, as did some of the crew; they were pissed off because they felt I was killing a good thing. My thing was, “It’s already dead and will be more dead if we don’t cut off the diseased leg.” I also think I might have done some people a favor by helping to prolong their lives.

The energy in the new lineup was immediately different onstage, too, where it felt like Gregg, Neal, and I were fencing each other and Michael was the guy in the middle, which actually was a good thing. When Dougie came in on bass, and with Mingo on the congas, it was a whole new kind of rhythm—more flexible and looser. That really was when I started to feel that maybe Santana could go in a different direction, one that would be evident on our fourth album, Caravanserai.

After we finished the US tour we flew for the first time to Peru to do our last concert of 1971—but something happened that stopped us from playing. And thank God we didn’t play, because we probably would have sounded horrible. Just think about it and repeat these words: rock band; Peru; 1971.

The twin brothers who booked us there were heavily involved with cocaine, so they met us at the plane in New York and brought a flour jar that was filled to the top. The party started in the air, and when we landed the whole Lima airport was filled with people—you would have thought the Beatles were coming on the plane after ours. We looked like… well, you know the story about Ulysses and the sailors who are turned into swine and grunt and act like pigs? That was Santana coming off that plane. By the time we landed the jar was almost half empty. I was ready to have another cold-sweat nightmare about going onstage and finding everybody in the band frozen like popsicles.

There was another part of the picture we didn’t know before we got there. Some people were not happy we were there—communist students who thought we represented American imperialism. Not everyone who hears the word America thinks of Howdy Doody and Fred Astaire. There was a protest, and someone started a fire in the place where we were going to play.

Later I heard that Fidel Castro wouldn’t let people listen to our music for the same reason. I also already heard that Buddy Rich used to throw people off his bus for listening to Santana. I’m okay knowing that we are not going to be everybody’s golden cup of tea.

When we got to Lima, we hung out with the mayor while our luggage went to the hotel. We got the key to the city, took some photos, and then we went to visit a few churches at my request—I was in Latin America again, and I wanted to see the churches. We were at the first one for just fifteen minutes when suddenly the place was surrounded by cops. They escorted us to a municipal building, where we waited and tried to figure out what was happening. The cops kept saying that everything was being done for our protection, but they revealed nothing else.

We were supposed to play the next night, and some guys were getting angry. Gregg was like, “Hey, man, fuck this.” I told him not to pull the John Wayne act. “I’m telling you, lawyers are not going to help you here, man. Be cool.” I could see that our situation was no different from being in a Tijuana jail. Then the cops told us there’d been some more problems with students; we were in danger, and we had to leave. They asked a plane that was flying from Brazil to Los Angeles to land and pick us up so that we could get back safely. We went straight to the airport. Our tour manager was Steve Kahn, who worked for Bill Graham—we called him Killer Kahn. He went back later to get all our equipment and luggage, which we had left at the hotel. He had to put on a wig to hide his hippie hair and shave his mustache so that he wouldn’t be recognized as an American.

So we get inside the plane that will get us out of Peru, and there’s only one place for me to sit—next to a weird-looking chick with raggedy blond hair who’s wearing a big muumuu. We took off, and she asked, “What happened?” I told her the whole story, then she looked around and said, “I wouldn’t worry about that. Look what I have.” She lifted up her dress, and it was like that guy in Midnight Express was sitting right next to me. She was a mule, and she had so much cocaine strapped to her that she looked pregnant. “Why don’t we go to the bathroom and do some coke?” Just what I needed. “No thanks,” I said. “I need to sit somewhere else, man.” As soon as we landed at the LA airport, the FBI and other people in uniform wanted to interrogate us about what happened. “Sure thing, man; let’s go.” I wanted to put as much distance as I could between me and that pregnant chick—and fast.

The story we got was that the government actually was trying to help us. I hear that people in Lima still talk about the time Santana came there but never played.

I was talking with Miles one time about changing the players in his bands and always going forward with his music. “It’s a blessing and a curse, man. I have to change,” he said. I liked the idea of a band being like that—loose and natural, open to the gift of new ideas.

I wanted Santana to be that way. But at the end of 1971, Santana was falling apart. Two of my oldest friends were gone from the band, and the mood in the band wasn’t pleasant—things were getting intense.

We could have used some time off the road to turn down the heat. When you’re busy playing and creating new music and recording—repeat, repeat, repeat—you don’t know how long to keep it going. You don’t know how long the phone will keep ringing with offers to do shows and make records. We never asked, “How much time can we afford to take off? A few weeks? A year or two?” But maybe we should have.

Santana III came out in October and was another number one album for us. I say “us” because on the first three albums everybody played his part and nobody told anyone else what to do. But when we started recording Caravanserai in 1972, I began to tell people what to do and what not to do. Santana III was the last album featuring most of the original Santana members, including Gregg. I could tell that there was a hurtful rub when I was in the room with certain people, and I’m sure it was the same for them, but what happened had to happen. When something is over, it’s over.

It would be around eight months before Santana got a new lineup and really got its groove together and went back on the road. It was the only time Santana did that—leave the scene for so long and come back with new personnel and a new sound.

We had gone from rooting for each other to tolerating each other to being two bands in one, in conflict musically and philosophically. On one side you had Gregg and Neal, wanting to do more rock tunes, and on the other side you had Shrieve and me. Chepito was always on his own path—dealing with his distractions and never really involving himself with what the band was doing or where it was going. He had songs that he wrote, and his sound will always be an important part of the band, but through all the changes that would happen in Santana, he always seemed to be in the dugout—never really in the game.

Shrieve and I were like gardeners, trying to let the music relax a little bit and grow on its own. We were listening to and thinking about jazz and rhythms and how many musicians we could meet and jam with. I think our way was more true to the idea of the original band, which gave everyone the freedom to say, “That was beautiful. Let’s try that again a couple more times, maybe in a different direction.” The big change was that by the time we were recording Caravanserai, I was the one saying that.