CHAPTER 15

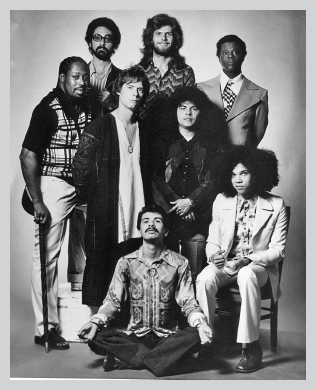

Santana, 1973: (L to R, top) Tom Coster, Richard Kermode, Armando Peraza; (middle) Leon Thomas, Michael Shrieve, Chepito Areas; (bottom) me, Dougie Rauch.

My time with Sri Chinmoy lasted from 1972 until 1981, and I believe both Deborah and I felt we got what we needed, that we benefited from his style of spiritual discipline—and that’s exactly what it was, a discipline. In an interview I did back in the late ’70s I said that I was “a seeker with Sri Chinmoy… even music is secondary to me, as much as I love it.” I think many people were surprised to read that then, and it’s still true. I was a seeker—now I feel I’m a guider.

I should be clear: it’s not about music or spirituality. For me, music is part of being spiritual, an extension of my aspirations in this lifetime. If I wake up only to be a musician, or only to go to work, or only to do this or that other thing, then I would be missing the big picture. But if I wake up and my first thought is that I am here to be a better person, then the musician in me is just going to come out naturally.

Music is the amalgamation of sound and intention and emotion and wisdom. To this day my chant is the same—“I am that I am. I am the light”—and that’s what I chant if I feel myself scattered, pulling away from my core, if I feel the Universal Tone separating into different notes. I need all that I am to hit that one note and be in tune. Five things go inside that one note: soul, heart, mind, body, and cojones.

I knew I had made the right decision to be a disciple of Sri Chinmoy when that feeling I had when I closed my eyes and heard him talking and chanting did not go away. The joy, the light, the lightness. When I went back to San Francisco and would visit the meditation center that Sri had started there, it stayed with me. When I would wake up to meditate at four in the morning, I felt the same way.

Love, devotion, and surrender—that’s the name of the path of Sri Chinmoy. Most people think of it as the album I did with John McLaughlin. Some even think that I joined Sri so I could play with John. That’s funny. First, it’s not easy to tell yourself to play guitar next to someone like John; and second, it’s much, much harder to be next to Sri! It was not like joining a garden club and meeting every Wednesday night.

The love part of Sri’s path is the thing that all gurus and spiritual leaders agree on—love is the unifying force of the universe; it’s what holds us together and brings us life. Love is the breath that flows through us all and connects us. Devotion is the commitment to living with spiritual priorities, which was the direction I was already going in when I started to move away from drugs and toward the idea of inner work; it was where I was going when I met Deborah, who was moving in the same direction. Devotion is not just inner dedication but also listening and learning a new vocabulary so I could talk about the incubation I was going through.

The surrender thing—that part was 100 percent Sri. Surrender was discipline—Sri’s discipline. It wasn’t just about short hair and guys wearing white shirts and pants and looking neat and women wearing saris. It wasn’t just abstinence from drugs and smoking. Surrender was about a pretty strict diet and schedule—agreeing to stop eating meat, agreeing to wake up at five in the morning and meditate for an hour or two hours straight, even when the brain and the body both want to do other things—anything but that. Sri was also one of the first gurus I know of who had exercise as part of his path. Sri was healthy, and he looked it, too.

One of the most important lessons I learned from Sri was his fearlessness—he believed so firmly in what he was doing that even before the whole guru thing was popular, he was doing it right in the middle of New York City. He wanted his disciples to be healthy, so he got us into jogging. Later he got into tennis and he put together teams and played with professionals. He wanted his disciples to be vegetarian, but there weren’t many places that served that kind of food back then—so he inspired people to start restaurants. John McLaughlin and his wife, Eve—Mahavishnu and Mahalakshmi—helped invest in and run a place called Annam Brahma in Queens, which was close to Sri’s ashram. Later, Deborah and her sister, Kitsaun, and I put together one of San Francisco’s first vegetarian restaurants—Dipti Nivas. I think eventually there were more than thirty of them around the world that Sri had helped bring into being.

Sri’s fearlessness in inspiring all this to happen in a world that mostly didn’t understand what he was about was one of the qualities I most respected. He didn’t just take his disciples and move to some jungle overseas, like Jim Jones did in Guyana. Jonestown was all about self-deception and darkness. Sri was self-discovery and light—right in the middle of Jamaica Hills, Queens.

If anyone asked me where Deborah and I lived in the years from 1973 to ’81, I would have said Queens first and San Francisco second. The reality was that between all the touring and recording and running the restaurant, which we opened in September of ’73, we would come out and stay in Queens usually three or four times a year. Each time it would be for around two weeks of meditation and exercise, like a pilgrimage. It was usually spread out through the year, and we were there for some special occasions, such as Sri’s birthday and Christmas, when we had to be there, and I’d make sure Santana’s schedule did not interfere with those dates.

When we were in Queens Deborah and I could relax and settle into the routine that Sri made for us: on most days around 4:00 a.m. we would wake up, take a shower, then go over to Sri’s house, because we were two of the few privileged ones—the first circle of disciples—who would meditate on the porch with him, which was a great honor. Then we would walk or take a nap, and later we’d have breakfast together. Deborah would work in the kitchen or some other enterprise such as the store, selling books and Indian saris, and I would help her or spend time speaking with Sri.

Later in the day Sri would talk to the disciples, play a little music on a toy organ, and get everyone to sing with him. Sometimes he’d sing songs he had written himself; sometimes he’d make them up right there and teach the words and melody to everyone. Then we’d stop and close our eyes and he would speak about music and its special power to make us aspire faster, to achieve a universal feeling of oneness, and to connect the outside—the music that man makes—with the music that everyone has inside but doesn’t always hear. One type of music helps reach the other—from one note to the Universal Tone.

The relationship I had with Sri was different from the relationship Deborah had with him, because I was not with him as much as she was. She would spend a lot more time with him while I was out on the road. I would come back and be overflowing with questions, wanting to know about how things functioned on the way to finding the light, and whether this or that was proper, and what she thought about various things. All the time I was with Sri I never called him Guru or Master or anything like that, but I showed him respect. He was a guide more than anything else, and it felt like I was part of a fellowship. It was a fellowship that I needed to return to so that I could be with souls who were aspiring toward the same path—just as certain people who want to climb Mount Everest or explore Africa will need to hang together and speak and support each other. Like attracts like.

It took a major commitment of time and energy from Deborah and me, and because of Sri and who he was, we were prepared to do it—a commitment of energy to excellence. For a number of years through the 1970s, our work with Sri was more rewarding than all the things the world was offering—the money, the praise, the other rewards that came from being in Santana.

I knew that I needed to surrender and do the things Sri required if I wanted to get past the ego games, get outside of myself, and have a different view of my persona. It was a commitment like being in the Marine Corps. Once you put on the uniform, you wear the uniform. This was spiritual boot camp—24-7—not just going to church on Sunday. I kept my conviction and my consciousness high, and I could feel much of myself changing. Everything started to change.

I think about it now, and these changes all made sense. It was as if they had been planned. One life change led to another and another and then one more—turning away from drugs and the crazy rock-and-roll lifestyle; thinking about spiritual questions and changing my diet; the band coming apart; finally accepting that I could not fix the break between Gregg and me; going in a different direction with the music; meeting Deborah; meeting Sri. I can’t see any of that happening if I’d still been smoking cigarettes or weed or eating junk food. It felt like it was all supposed to happen—later I understood inwardly that it was the invisible realm working its way through me.

It was my own inner journey, but to the fans of Santana and people around the band I was still the same Mexican guy onstage with a guitar every night hitting those notes. They didn’t know what was going on until I showed up dressed all in white, with my long hair cut short. Even people close to me, including other members of Santana, didn’t see these changes coming. When Deborah and I got to London at the end of 1972 for the European shows, everyone thought I’d gone off the deep end. Everyone except Shrieve, of course, who joined Swami Satchidananda.

When I got back to San Francisco, everybody including my mother thought I had lost my mind or just given it away. My family and friends from the Mission were the most certain of it. “You’ve been brainwashed. Those people will eat your brain—there is nothing happening but Jesus Christ, and that’s it. Anything else is the devil.” My dad was the one who was cool about it. He honored me by not saying anything, respecting my decision, and allowing me to work it out and find out what it was all about.

To the older guys who had left the band—and of course to Bill Graham and Clive Davis—this was just one more piece of evidence that I didn’t know what I was doing, that I was willing to commit career suicide. Most of them didn’t say anything, but I could feel it—and their suspicions didn’t go away until 1975, when we went back to the older Santana kind of music. Until then, every now and then people would point to other Latin rock groups, such as Malo and Azteca, and say, “Man, they’re playing Santana better than Santana is, know what I mean?” I knew exactly what they meant, but still I’d look at them and say, “No: what do you mean?”

The one guy who kept at it was Bill. He came by the house a couple of times, and I’d say, “What’s up, Bill?” and we’d talk. One time he was being very polite. “Can I come in?”

“Sure.”

“You know I love you like a brother, like my son,” he said, and he started crying.

I said, “Bill, what’s going on, man?” He shook his head. “The decisions that you’re making are breaking my heart because I can see how hard you’ve worked so far, and it feels like you’re just throwing it away.”

Bill had been taking things hard not only because of my decision to go with Sri Chinmoy and to change the sound of Santana but also because there was a big problem with how things had been managed—mismanaged—in our business. Money had disappeared and taxes hadn’t been paid, so the IRS was getting involved, too. Almost all the money we thought we had put away had leaked out. That year, partly because we were told we’d better keep busy to make the money back, Santana played more shows than ever—we were constantly touring.

Yes, our music had changed, but people still wanted to come out and see Santana—they were buying tickets. I said, “Bill, now I’m going to cry. But if I do what everybody tells me to do, man, it won’t be me. I know you want to encourage me to make better decisions, but I’m not going to kill my career, and I’m not going to let anyone kill who I am, either. I have to go through this with Sri Chinmoy, and I’m working on this thing with Deborah.” I told him, “Bill, it’s just that simple.”

By that time Deborah and I were living together. I remember the day I knew we had crossed that line and I could tell that we were a couple. She called me over to her, and she had the keys to the Excalibur in her hand. She was making a face, holding the keys up with just two fingers, like she was holding a dead rat. “What?” I said. I had no idea what she was doing. She said, “Now that you’re with me, you’re not going to need this.” I said, “What do you mean?” Then I got it.

I was thinking, “Who does she think she is? That’s audacity, man.” But I liked how she did that—she had my respect, and I could feel right away what my answer was. I said, “I’ll tell you what—you don’t like it, you get rid of it.” I think Deborah sold it in half an hour.

That’s when I knew that we were in it for the long haul. In April, Sri was talking to us, and he said that he could see we were good together, that we were helping each other with our spiritual progress. He said, “You two should get married.” We looked at each other with questioning in our eyes, because back then young people were not so formal and were pulling away from those kinds of old, traditional ways. I was twenty-five and Deborah was twenty-two and we were in love, but we hadn’t even been together a year by then. I think we could have lived together forever at that point, but Sri convinced us that he saw something more. “I think your souls need to be tied together—this will help you both with your aspirations even more.”

When Deborah and I got back to our place, she asked me, “What do you think?” I answered, wanting to first get her reaction: “What do you think?” We went back and forth like that, neither one of us wanting to take the first step. It wasn’t a very romantic proposal, I admit, but then again I hadn’t really been trained in that department. We did love each other and wanted to be together, and we wanted to be on our spiritual path together, and Sri had told us how that should happen, so we decided to go ahead.

Deborah quickly told her parents, and not long after we got back to San Francisco, on April 20, 1973, we got together at city hall to sign the forms. Then we held a small ceremony and reception in Oakland, at SK’s brother’s house—he was a preacher, and he married us, too. I remember wearing funky white platform shoes, which made me a lot taller than Deborah, and I remember I wore a tie. I think I had shaved only half of my face. I also remember that everyone asked if my parents were coming.

In fact, I didn’t invite anybody when I got married—no one. No family and no friends. Deborah’s mom asked, “Where are your parents and your sisters and brothers?”

“They’re not coming.”

The rest of the guests looked at me with their mouths open. “They’re not coming?”

“No.”

“Why aren’t they coming?”

“Because I didn’t invite them.”

In the ’60s, when things were going smoothly, as they were supposed to, almost with no special plan, we’d say it was a groove. That’s what our wedding was like and what my priority was—very quick and simple, no hassles. Deborah and I were in love, and we were living together, and that’s what seemed important then—we knew we would also be having a divine ceremony back in Queens with Sri.

The hassle that I wanted to avoid was my mom—we were probably farther apart then than we had ever been, and we had not seen each other for a while. I was still holding on to all the hurt that came from that list of things she had done beginning in Mexico, such as spending the money I had saved for a new guitar. The tension in my muscles when I thought about that was still there—it would take years before that started to release. That’s how I was feeling about the idea of a ceremony, anyway. When Jo asked me why my mom wasn’t at the wedding, I didn’t know what else to say. I told her, “My mom is very domineering, and she would want to change everything.”

I did call my mom afterward, with Deborah next to me, and told her that we had gotten married. I could tell she was hurt. There was silence, and after I hung up I didn’t know what to say to Deborah. When we had our second wedding in Queens with Sri Chinmoy, another very simple and unpretentious ceremony, Deborah persuaded me to invite my family. I remember flying to New York with my father, mother, and my sister Laura on the plane. The whole way over, my mom was letting me have it—making it really difficult—and she didn’t care who heard. All I could do was sit there and take it—this time I couldn’t walk away; she had me. I remember looking at Laura, and she was just shaking her head, trying to look away.

I’d never seen my mom so hurt; I’d never seen her react that way. The whole trip she would bug out and start crying and then get angry again. Laura would try to step in and be the shock absorber, and I would say that this is what I didn’t want to have happen at the wedding in San Francisco. I knew that I wouldn’t have done anything intentionally to hurt my mom, but still I had done just that by ignoring her and keeping her out of my life. I was already getting closer to Deborah’s family than I was to mine—I remember we spent our first Thanksgiving after getting married in Oakland, cutting the turkey and watching O. J. Simpson break another football record in Buffalo. To me it felt natural. Her family never made me feel anything but invited—“Come on, you want some more sweet potato pie? How about more of this?” Just like that.

I was still young and growing up and evolving, and I still had a habit of going away if I saw a verbal conflict coming, especially with a woman. I could feel a door close, and I would be gone. It was automatic. That was one of the things I had to take care of with the inner work I did. I’ll say it here: all the prayers and the spiritual coaching, all the inner and outer adjusting—I now see that it was really for my mom, which is why I’m dedicating the book first and foremost to her, with my thanks for being so strong and patient.

It would take a few more years for my mom and me to really get together again, and for almost the last thirty years of her life we were the best of the best. Before that, it was rough for a while. It was a crazy time, and I was so discombobulated with thoughts and emotions. I’ll put it this way: I wasn’t all the way present.

Even at our first wedding, when it was just Deborah, her family, and I in Oakland, I told her family that I couldn’t stay for the reception because I had a rehearsal with the band. Once again, they looked at me like they just couldn’t believe it. “Thanks for a great wedding day, everyone, but I got to go and get ready for this next tour.” Deborah knew about it, but I don’t think I was scoring many points in my favor that day. I went out to the car, and because it wasn’t the Excalibur anymore I forgot what to do and had locked the keys inside.

I remember standing there with Deborah while SK worked a coat hanger into the window to open it for me, all the while looking at his little girl so hard I could hear what he was thinking. “Are you sure you want to marry this Mexican cat?” Over the years, whenever Deborah and I got into it, she’d say, “I should have known right then that it wasn’t going to work.” But we stuck it out.

In April of ’73 we started working on the next Santana album, the follow-up to Caravanserai, staying with the same jazz flavor and spiritual vibe. By that time we were running on our own steam. Who was around to tell us anything anymore? Maybe Bill, but CBS had fired Clive Davis around the time we started the new album, which was called Welcome, and we didn’t have a tight connection with anyone else at the record company—not the way we had with Clive. The people who came after him did what they had to do, but I never really did work with any other record person who understood and could speak to musicians the way he did, except for Chris Blackwell at Island Records.

There was also no one left in the band to complain about changing our style or going in a different direction—Shrieve, Chepito, and I were the only guys left from the original lineup. Still, that didn’t help me with the transition—the change in the band and the changeover to the next part of my life were still spinning around in my mind. I actually played John Coltrane’s music over and over and over and over, for focus. I still do.

This time the title track, “Welcome,” was actually a Coltrane tune. Shrieve and I talked about who should be on the album. We liked the idea of two keyboards and also two percussionists, which we had on Caravanserai, so we kept Richard Kermode and Tom Coster, and there was Chepito, who was the Tony Williams of the timbales, and Armando, who—well, he was the Armando Peraza of the congas! Dougie, of course, stayed with us on bass, with his nice, funky consistency, and we invited some special friends, too—some of the same people from the Bay Area who played on Caravanserai—plus John McLaughlin, the saxophonist Joe Farrell on flute, Jules Broussard on soprano saxophone, and others.

For some reason I didn’t pay as much attention to the guitar player as I think I should have on that album. On Welcome, I focused on the moods of the keyboard players and congas and timbales and stuff like that. The one tune I really thought about for my guitar was “Flame-Sky,” which has McLaughlin on it. The title comes from something Sri said when I played him the song.

“You’re such good boys, you and John”—he said that endearingly about us. “If you could only see how you affect the audience—both of you inflame their hearts to aspire again to be one with God. Most people forget, and they invest in a nightmare of separation and distance from their Creator and they play roles they make up, but the only role that is real is the undeniable relationship with the Creator and being in your own light. When people hear this song, a flame will shoot out of their hearts straight up to the sky, which will tell the angels, ‘This one is ready. This one is aspiring and not desiring.’”

Another thing I remember about that tune: when John and I did our tour together later that year for around two weeks, we played “Flame-Sky” to open our shows and always closed with “Let Us Go into the House of the Lord.” What a great band—John brought Larry Young and Billy Cobham, and I brought Dougie and Armando. I remember that Armando took on Cobham in one rehearsal after Billy said that he’d never met a conga player who could keep up with him—congas versus drum kit. I thought it ended in a draw, but Armando was still unimpressed. He held up his hands and said, “I don’t need no stickets.”

The first three gigs were really fast and loud, and I could see people yawning and covering their ears and walking out. In Toronto I told John we needed to have a meeting with everybody. “Okay, Little Brother. What’s going on?”

“I think we need to do some sound checks and really rehearse some of the intros, the endings, and the grooves, because all our songs are sounding the same. We need to break down the songs, bring down the volume, and put a groove in some parts. Slow down a few and add some variety. I’m not used to people yawning and walking out of our concerts.”

We had our meeting, and I might have been a bit immature in the way I called out the group for being unprofessional, which hurt some feelings. Eventually I heard that John had said that not even Miles talked to him like that. But I was surprised that nobody else had brought it up. I was feeling that if you’re going to pack a place with thousands of people, as we were doing, you owe it to them not to play like it’s a Tuesday night at some little bar. Something good came from my speaking out, because we started playing different moods, creating valleys and meadows and mountains. It was very successful. And yes, I was working on knowing how to talk to the band. I’m still learning.

The big question for the Welcome album was vocals—who was going to sing after Gregg left Santana? We looked at our record collection again, and we thought about Flora Purim and invited her to join us. She came from Return to Forever and sang “Yours Is the Light.” I really liked Pharoah Sanders’s album Karma, on which the song “The Creator Has a Master Plan” was sung by Leon Thomas, who sometimes liked to yodel. Leon was doing his own albums at that point: he put words to Gábor’s “Gypsy Queen,” and he was being produced by John Coltrane’s producer, Bob Thiele. Asking him to record and tour with us was Shrieve’s idea: “What if we get Leon Thomas to sing ‘Black Magic Woman’? Can you imagine that with him?” I said, “Okay, let’s do it!” and Leon agreed. I love Leon’s singing on Welcome—on “When I Look into Your Eyes” and on “Light of Life,” with strings arranged by Greg Adams.

My friend Gary Rashid—Rashiki—had just started working with us then. His very first job was to go to the airport and meet Leon, and he was asking, “How will I know what he looks like?” Leon arrived wearing a kind of safari outfit with a big hat and a cane. No problem. Leon became an important part of Santana, recording and then touring with us from spring of ’73 through the end of the year. But at the start I don’t think he really trusted us to treat him right. He saw that I was eating a specially prepared vegetarian meal every night, so he told our tour manager he wanted something special. “Okay, what would you like?” the manager said.

“Liver and onions”—which I think was like asking for a high-priced menu choice like steak. So our tour manager made sure that at every meal—in the hotel and backstage—a plate of liver and onions was waiting for Leon, and you can guess what happened. By the third day he was done with that. “Don’t you guys get to eat anything but liver?”

The first tune on Welcome is “Going Home,” which was inspired by Antonín Dvorˇák’s New World Symphony and was arranged by Alice Coltrane. I asked Richard Kermode to play her arrangement on the mellotron and Tom Coster to play the Yamaha organ the way she played her Wurlitzer. I’ll be honest: Shrieve and I had Tom in a headlock, telling him he had to listen to Alice Coltrane, to Larry Young, to Miles playing the Yamaha, and God bless Tom, because he never threw up his hands and said, “Fuck it” and walked away. Instead his attitude was, “Okay, I’ll try it.” Once he got the tone down, it was all easier after that.

“Going Home” came out of meeting Alice Coltrane that year, which for me was maybe the biggest realization of my spiritual dream—going from being a dishwasher to meeting the widow of John Coltrane and then getting to make music with her.

We met for the first time in the spring of ’73, when Alice invited me to come stay with her in Los Angeles so that I could meet her and her friend Swami Satchidananda. By that time she had adopted the Hindu name Turiya. I liked Satchidananda, and maybe he was another guru I could have followed, but I can be intense, and I think that Sri’s own power and intensity were good for me. If there’s such a thing as discipline in romance, then that’s Sri Chinmoy, because he is a lover of the supreme, and I tend to gravitate to lovers. When they hug you it’s really close. They’re not going to let go.

Deborah and I were making a life that had two homes, one in Marin County and the other in Queens, at the place we rented on Parsons Boulevard near Sri’s ashram. We were going back and forth, and we had enough trust already in our marriage that she could go to New York and meditate while I stayed and recorded in San Francisco. So when Turiya invited me to spend time with her, which she did after she got to know about me from Love Devotion Surrender, Deborah knew that it was an opportunity for me to develop an important musical and spiritual relationship—one that needed to be developed. So Deborah went to see Sri in Queens while I went down to Los Angeles.

We’re all interconnected anyway, but I felt more open than I had at any other time about playing music and learning. I tried to take all the lessons I could find from the teachers I could find. You could say that during this period, all the meditating and discussing and listening I was doing were like peeling an artichoke, pulling away the outer layers to get to the core of who I really was, who I’ll always be, without playing the hide-and-seek games that people play with themselves.

I spent close to a week with Turiya. She opened her house to me, and I was very grateful that she did. I remember listening to her speak about music and her spiritual path and of course about John—but she never called him John. It was either Ohnedaruth, his spiritual name, or a few times she called him the Father. She used to tell me that he never stopped playing, even when he was home, long after a gig. When he had the day off, he’d still be at it—she told me that he could spend an hour just looking at the saxophone in front of him and then another hour fingering it up and down, all over the horn. Finally he’d put it in his mouth and start playing—hallelujah! So first he visualized the music, then he got to the mechanics. I think Coltrane wouldn’t stop thinking about and playing the horn because he didn’t want the stove to get cold—if it does, you have to start all over again.

I also spent time hanging around Turiya’s children. I watched them jump in the pool during the day, and every night after the kids went to sleep she and I would talk for a little bit. She’d go to her room, and I’d relax on the sofa. Then around three thirty in the morning, we’d both get up, and she would play the harp and the piano. I would listen, then we’d both meditate some more.

One morning, almost at the end of the week, we started meditating. When you meditate at three in the morning, the first half hour is like being on a plane flying through turbulence. Your eyes are red, you know it’s dark all around you, you’re trying to stay awake, and you’re shaking. Then all of a sudden things get really smooth. That morning I could see a beautiful flame in the candle that was burning—it was like a flame inside the flame. So in my mind’s eye I went into it, as I had done many times before. But this time I began to feel the presence of somebody in the room besides Turiya. It was John Coltrane. Then he materialized in my vision. He was looking right at me—and he was holding two ice-cream cones, each of which had three scoops!

I looked at John, and he smiled and said, “Would you like to try some?” Then it was as if Turiya had entered the vision from the corner of my left eye, and she said, “Go ahead and try one.” So inwardly I took one of the cones and licked it, and it was sweet and creamy—just delicious. “Good, huh?” John said.

“Yes, thank you. It’s very good.”

“Well, that’s a B-flat diminished seventh chord.”

“What? Really?”

Then I heard Turiya say, “Try another one,” only it seemed like she was saying this out loud in the room next to me, like she knew what was happening in my meditation.

Man, that freaked me out. How did she know? I have no doubt when people read this they’re going to say something like, “Oh, sure—this cat just took too much LSD, and the hallucinations were still coming.” But I stopped doing drugs from ’72 to ’81. Maybe once, a year later, I’d get curious again and try a hit of mescaline, but at that point in ’73 I was really straight—totally clean.

You have to understand that to this day, when I listen to John Coltrane’s music, it reassures me that God never lets go of my hand. No matter how dark things get, God’s still in me, no matter what. For me his music is the fastest way of getting away from the darkness of the ego—darkness, guilt, shame, judgment, condemnation, fear, temptation, everything.

It’s not just A Love Supreme and Meditations and his more spiritual albums. If I hear “Naima” or “Central Park West” or “Equinox” or “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”—or any of the older ballads he recorded—I find that every note is laced with spiritual overtones. There’s always a prayer in there that anyone can hear.

Even when Coltrane is playing a song, it’s much more than that—and I like songs. I like “Wild Thing.” I like “Louie Louie” and anything by the Beatles or Frank Sinatra. But Coltrane wasn’t just about songs—at least I don’t think he was. His music is about light, and his sound was a language of light. It’s like the solvent that they put into dirty, murky water: stir, and instantly the water goes back to being clean. John Coltrane’s sound is a solvent that clears the muddiness of distance and self-separation. That’s why we all love Trane—Wayne Shorter, John McLaughlin, Stevie Wonder, and so many others—because his sound reminds us that everything is redeemable. That’s what Coltrane was telling people: crystallize your intentions, your motives, and your purpose for the highest good of the planet.

I never was able to meet Coltrane, but I feel him through so many other people—Alice Coltrane, of course; Albert Ayler; John Gilmore—especially through their spiritual practice and their intergalactic music. Today you can still hear Coltrane in Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock and in the music of Charles Lloyd, Pharoah Sanders, Sonny Fortune, and many others.

I know some people scratch their heads when I tell them that John Coltrane’s music has the power to rearrange molecular structures. I found myself once at an Olympics ceremony—I was talking about the healing power of Trane’s music, and Wynton Marsalis was next to me. He shook his head and made a face. I just cracked up. Maybe Wynton’s changed his perspective, but at that time I could tell he didn’t want to hear what I was saying. You know, it’s such a blessing to be able to play from your soul and to reach many people. It’s also a blessing to be able to listen and hear the healing power that comes from other people’s music. That is what I mean when I talk about the Universal Tone.