CHAPTER 16

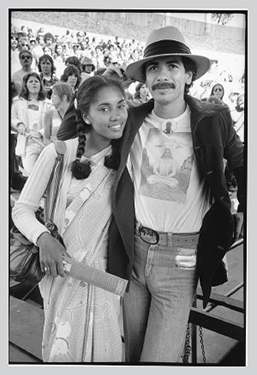

Deborah and me, Day on the Green at the Oakland Coliseum, July 4, 1977.

Around 2004 I had a very, very meticulously detailed dream. Check this out: I was in a building in Milan at night. John McLaughlin was there, too, and we could see outside through a window to a park with really bright lights in the middle. They were like interrogation lights, so it was dark everywhere except where the lights were shining, and some guys were playing soccer there, but they couldn’t go too far because they had to stay in the light. So John and I were watching this soccer-in-the-lights game, and suddenly I saw Todd Barkan—the guy who ran the Keystone Korner jazz club in San Francisco—walking across the park, and with him is somebody who’s carrying some saxophones and pushing a bicycle. It was John Coltrane!

John and I watched the two men come up to the building we’re in, and we were getting more and more excited. Coltrane left the bicycle outside, came up with his horns and some sheet music, and Todd introduced us. “Hey, Carlos, John’s got a song that he’s working on, and I think he wants you to play with him.”

“What? Really?”

Coltrane looked at me. “Hi; how you doing?”

“Uh, hi, John.” I was so nervous, just thinking, “Oh, my God, I’m with John Coltrane, and he wants me to play something with him!” I looked at the music as Coltrane was taking his horns out, and it was a black church song, something like “Let Us Go into the House of the Lord.” I was thinking, “Oh, yeah. No problem. I can handle this,” and I started working on my part.

But when I looked up Coltrane was suddenly gone. I asked Todd, “Hey, what happened to John?”

“Oh, man, somebody just stole his bicycle, so he went looking for it, but I think the thief got away.” So I decided to help him and left the building, and suddenly I was on the parkway between Nassau Coliseum and Jones Beach. I saw Coltrane’s bicycle, but it had been stripped—the wheels and the seat were gone. I picked it up anyway and brought it back with me and found John. Then, with a jolt, I woke up.

Man, that dream left a powerful impression on me. It was still early in the morning, but I had to tell somebody, so I called Alice: “Turiya, I’m sorry to call at this time.” She said, “That’s okay—I’ve already done my meditation. How are you?” I told her about the dream, and she said to her it made perfect sense. She broke it down this way: she felt that the kids playing in the park were the kids who listen to music today, bouncing in and out of the dark, looking for music that will bring them into the light, music like John Coltrane’s. The stolen bicycle with no wheels represented how difficult it was for that music to find a way to get to people. There was no vehicle anymore to help carry Coltrane’s music to those who need to hear it. His music gets so little airplay and so little press, but it’s important to bring people into the light of his music—to make Coltrane a household name.

I’ve been trying to put the wheels back on that bike since 1972 —recording “A Love Supreme” and “Naima” with John McLaughlin, recording “Welcome” and “Peace on Earth,” pointing people to John’s music and to Alice Coltrane’s sound, which, I believe, is sadly overlooked—but her music is really timeless, too.

I have lots of other ideas. I went on a quest to get the Grammy people to name their annual lifetime achievement awards after him: the John Coltrane Lifetime Achievement Award. I’d like to put together an entire album of Coltrane performing “Naima”: three or four disks that include some of the best performances he did of that beautiful song, live and in the studio. I support Ravi Coltrane, John and Alice’s son, and his wife, Kathleen, in all they’re doing to preserve the Coltrane home in Dix Hills, on Long Island, where Coltrane wrote A Love Supreme and where he started his family with Alice.

There’s another thing about that dream of John Coltrane and the bicycle, and people are free to say that I’m tripping. They wouldn’t be wrong, either—in some ways I think I was born tripping! But many times it’s hard to tell the difference between dreams and imagination. Anyway, the same morning that Alice Coltrane interpreted the dream, I got a phone call from my friend Michel Delorme in France. I told him about the dream, gave him all the details, and he kind of shrugged it off in his typical way: “Poof! Of course, Carlos. I am on the road with McLaughlin. We were in Milan just last night, talking about you and John Coltrane.”

The year 1973 was one of spiritual discipline, and it was also a year of extreme endurance and madness. It felt like Santana was on the road more than we were at home—some nights we did two sets. By my estimation I think we did more than two hundred shows. Why did we work so hard? A big part of it was the feeling that while people were paying, we should be playing. We didn’t have enough confidence to believe that the audience would still be there if we took time off and then went back to New York or London or Montreux. We also didn’t know better—if our manager was telling us that we needed to be making a certain amount of money, and if we were hurting because of the IRS, who among us had the experience to stand up to that? We were young, we were eager, and we believed in our new music. It was our decision. Nobody was putting a gun to our heads.

What helped me was that I was meditating and my diet was healthy and I wasn’t partying, and Shrieve was the same way. This was when we started to have incense onstage and when I put a photo of Sri Chinmoy in deep meditation on my amplifier. I don’t think I could have made it through that year without the spiritual strength to support what we were doing on the road. We had traveled a lot before, but you can ask anyone who was in Santana that year—there were times it was like going to war. For me, it felt like Shrieve and I were comrades on the battlefield. It was hard, but we were in love with the music, and nobody ever complained.

When I look back on those times, I realize that I wasn’t always the easiest guy to be around. I was like an ex-smoker hanging with a bunch of smokers and telling them that they needed to change. I think that like most people who are not ripe with maturity or spirit, I tended to get all huffy and puffy and holier-than-thou. Maybe I did come across as having a sense of superiority and some kind of rigidness about the spirituality thing. I’ll put it this way: there was room for me to grow, and it took me some time to realize it.

I think a few of us who were following Sri Chinmoy back then felt that we had some sort of key to heaven and that everybody else was a dumbass. I wish Sri in his teachings had also said, “Look, if you’re going to be on a spiritual path you need to be gentle with people who are not going the same way.” I didn’t know it, but I had much growing to do—I was still very, very green at conducting myself with gentleness toward people. By contrast, I could tell from listening to the interviews John Coltrane did that he was very considerate of other people’s spiritual unfolding, or their lack thereof, whenever he spoke. That was what I needed to aspire to—not just his music. There was a lot of learning going on in 1973.

The other thing that made it easier for me that year was that I think the band was one of the most amazing versions of Santana ever. Actually, I’ll put it this way: in hindsight, that 1973 band—with Leon Thomas, Armando and Chepito, TC and Kermode, Dougie, Shrieve, and me—was musically the best and most challenging band I’ve ever been in. And the thing is, when we were playing at our best we were really just trying to find ourselves.

That lineup was the closest I think Santana ever came to being a jazz band. At sound check we would try out new things, and it was fun. I remember we would take inspiration from little musical segments written by a keyboardist named Todd Cochran, who wrote for Freddie Hubbard and others and recorded his own music, too. He had a song called “Free Angela” that we started doing, which I thought sounded like it could have been on Herbie’s album Crossings. To this day we have sound checks and try out new stuff all the time, even if we’re in the same place for two or three nights and have already tested out the system. “You still want to do a sound check?”

“Yes, of course. Let’s try something new…”

I think the best way to explain that year is to start with Japan—that was our first time in that country and that part of the world. Like Switzerland, it became a country Santana came back to again and again, and it was where we found another enlightened music lover, like Claude Nobs in Montreux, who had become a big music promoter there—Mr. Udo. Some people call him the Bill Graham of Japan, because he was the man who really started bringing big rock acts there. I agree with that, but he also earned his moniker because he respects the music and treats the musicians well. He never stopped believing in Santana and what we were doing—ever. He’s always been dignified, a snappy dresser, and always has some great stories—when he laughs he doesn’t hold back. He’s another keeper of the flame, one of the angels who arrived at just the right time to guide and support us. Mr. Udo is the only promoter I have ever worked with in Japan.

When we came through in ’73, Japan was still very traditional—you could see there were as many people in kimonos as there were in suits. McDonald’s wasn’t there yet, and neither was Kentucky Fried Chicken. Mr. Udo made sure we ate well, though, and he was always the perfect host, taking us out to dinner—he still does that, and I still make sure we leave time for it when Santana goes to Japan. On our last visit there he presented Cindy with the most beautiful, mind-blowing kimono decorated with all this embroidery, which made her just melt—it was fun watching my wife turn into a six-year-old!

Japan has always been the best place to get the newest electronics, especially stereos. The Japanese had Beta-format videos when those first came out and compact discs and DATs when no one else had them. That first time we were in Tokyo, we discovered Akihabara, the district where all the electronics stores were set up, and that’s when I found out that Armando, with all his supreme confidence, was also a supreme bargainer.

He was amazing to shop with and watch. Armando had a routine in which he would go into a store and pick up a tape player or something, put it back down like it smelled bad, go away, and come back to it as if he felt sorry for it. Then he’d say to the salesman, “Remember me? My name Armando Peraza. Here with Santana. This… thing… special price for me? How much?” The salesman would be smart enough to know what to say. “It’s three hundred and ninety-five dollars. But for you, three hundred and fifty dollars. And maybe a good deal on some headphones.” Armando would say, “Hmm. That’s not too bad. Write that down for me.”

Often I could tell that this was the first time anyone had asked the salesman to do that. So the man would write down his offer, and immediately Armando would go across the street to another store, where he’d been just ten minutes before. “Hey, remember me? Armando Peraza from Santana? Look at this—same thing you have here. He wants three hundred and fifty dollars. What can you do for me?” So he would get the price down to three hundred and twenty dollars. “That’s the best you do? Because everyone in Santana is looking for this thing, too—I bring them all here to you. Just write the price down for me—I show them.” You can guess what would happen next. Armando would go back to the other store and walk away with something like a 40 percent discount. Then the two salesmen would phone each other to talk about that crazy Cuban!

Armando wasn’t that way just with electronics—he loved nice coats, and he was a shoe addict, too. It was fun to watch Armando at work—I learned a lot.

In Tokyo, Mr. Udo had us play a whole week at the Budokan, a beautiful arena that had been built for judo competitions. The Beatles had been there in 1966, and it became another jewel in the rock touring world, one of those places every group had to play—and record, if they were lucky. Our shows were taped for TV broadcast and packed every night. I thought maybe it was time for the first live Santana album to come out—and so did Mr. Udo. So we also recorded our concerts in Osaka in another beautiful theater called Koseinenkin Hall. It was such an amazing experience: the love and respect from the audiences, the support from Mr. Udo, the level on which we were playing. When we left Japan to play Australia and New Zealand, I knew we had recorded some of the best music we had ever performed.

We did the tour of the Far East and Australia on a plane we rented—an old propeller plane that Chepito nicknamed the Flying Turtle because all our trips seemed to take forever—I remember that going from Hong Kong to Perth felt like a twenty-four-hour flight. But at the time it didn’t matter, because we were so high on the adventure of it. We’d finish playing a great show and be buzzing, then we’d get on the plane and I’d close my eyes and wake up in a new country I’d never seen before—Indonesia, Malaysia, Australia. I was also really high because the press was complimentary, even though they might have been disappointed at not having heard the original Santana band and the kind of concerts we were doing back then.

The last concert of the tour was in New Zealand—Christchurch—and I remember the band being so together, as if we had made it to the summit of a mountain. It really felt like the best concert of the tour, the best that band had ever sounded. We didn’t record all our shows back then, but I knew that fans were able to either record Santana in concert or find people who did. I knew that there were bootlegs floating around, although it wasn’t as extreme as the Grateful Dead’s situation with the Deadheads and all the taping and trading that went on. For some reason, though, I wasn’t able to find a recording of our Christchurch show until 2013, when we got a copy through one of our dedicated Santana followers. We call them the gatekeepers because they know more about the band and its history than just about anyone. The recording needed to be fixed in the studio, because the tape had deteriorated and was wobbly. But once it was repaired, the playing sounded crisp, and it validated everything I remembered feeling about the show. There was a sense of adventure in our playing; we were stretching out and trying new things, even on the last date of the tour, and there was no more turbulence—no problems with the structure of songs or the segues. It felt like the show just played itself—it was that good. It still blows my mind.

From there we went back to the United States and toured for another five weeks. It was during this period that Deborah and I got our spiritual names from Sri, which he had promised us the year before. Devadip, which means “lamp of God” and “eye of God,” was my new name; Deborah’s new name was Urmila—“Light of the Supreme.” At this same time, Deborah and Kitsaun were getting ready to open Dipti Nivas, the vegetarian restaurant that Sri asked us to start in San Francisco because he would not accept any donations. He preferred that his followers do the kinds of things that expanded his message of love. “Do not try to change the world,” he would say. “The world is already changed. Try to love the world.” A new vegetarian restaurant aspired to that spiritual goal and was the kind of contribution he wanted.

The restaurant opened in the Castro, which was becoming known as the center of San Francisco’s gay community, and as the neighborhood grew it helped all the businesses there. At first I wasn’t sure if we were ready to run a restaurant, but I got to see Deborah in charge, and because Kitsaun was also a disciple by then, I knew the two of them would be okay. I remember Deborah once going up to a tall drag queen and saying, “Excuse me, sir. There’s no smoking allowed.” He looked like he had spent half the day getting himself together. He looked down at her and put out the cigarette. Deborah was no-nonsense when it came to that.

Soon anyone who was vegetarian or was thinking about giving up meat or was just curious came by. The frittatas and casseroles and fresh juices were delicious, and the place got great reviews. Deborah and Kitsaun started doing meditation classes there, and bands such as Herbie Hancock’s came in to eat when they were in town. The name for what we were doing was what Sri first called it—a love offering. People could taste our intention and feel what we had to offer on a spiritual level. Dipti Nivas stayed popular for a long time.

The next leg on our tour was Santana’s first real run in Central and South America—ten countries, including Mexico. It was my first time playing there since I left in 1963. In fact the first show was in Guadalajara, in my home state of Jalisco, so you can imagine the attention I was getting. I’ll be honest: I don’t think I was ready for it. I was still getting myself together spiritually, still figuring out my identity. And musically I was much more American than anything else, still loving the blues and the jazz of Miles and Coltrane. In my mind, even before I met the press in Mexico I was already thinking that they’d be wanting to claim me. You know what the first questions were when we started doing interviews? “Why don’t you play Mexican music? Don’t you like music from your home country? Why don’t you speak Spanish?”

Asking me those kinds of questions was like waving a red flag in front of a bull. The reporters would do the press conference in a very confrontational way. My mind was spinning with all kinds of possible answers, like: “I’m not Mexican, I’m a Yaqui Indian, like my father.” Or “You know, what you think is Mexican music is really European—two-beats and waltz rhythms. Even the word mariachi comes from the French word for ‘wedding.’” But interviewers were looking for a lesson in music history about as much as I was looking for an interrogation.

Things between those Mexican writers and me did not get off on the right foot. There was a bit of a war between us that went on for years: even my mom heard about it back in San Francisco. Friends would send her the newspapers, and she’d call me. “Can’t you tone it down a little bit? You might be telling them the truth, but you’re pissing them off like crazy.” She read everything. “Why are you so angry?” she’d say. My whole family has been like that—Tony, Jorge, now Maria—checking up on me, asking me to watch my words. That’s a family tradition now; even if I sometimes have to respectfully disagree with them, I love them even more because they care so much.

Things did get better with the Mexican press over the years, and it never stopped me from going there and playing the same kind of shows I do everywhere else in the world. It took time—when I went back after Supernatural hit I think that was the first time I really felt comfortable being Mexican and being in Mexico, even with all the questions I would get. One thing’s for sure: there never was a time I did not feel the love of the people when I played there. Mexican audiences always made me feel right at home—even that first time, in ’73.

One highlight of that tour made me extra proud of being a Mexican. When we got to Nicaragua, Chepito’s home, we agreed to play a benefit for the survivors of the huge earthquake that had hit there just before Christmas the year before. Actually, this was the second benefit we did—the first one was in California the previous January, with the Rolling Stones and Cheech and Chong. This time we played in a soccer stadium right in Managua, where the earthquake had hit. Who was the emcee for the show? I couldn’t believe it—Mario Moreno, or, as every Mexican knows him, Cantinflas!

Everyone in Central and South America knew the movies of Cantinflas and loved him. He was like all the Marx Brothers rolled into one—making fun of rich society people; getting away from the cops; getting over without changing who he was. The fans crowded the airport when he arrived. When he got onstage at the stadium, the placed was packed. He went up to the mike and said, “Hermanos, hermanas! I got a phone call while I was in Barcelona that I was needed here to be master of ceremonies tonight, and I said right away, ‘Of course! For my brothers and sisters in Nicaragua, of course.’” The stadium was filled to the top, and everyone was cheering. Then Cantinflas got serious. “I have just one thing to ask.” The whole place got quiet.

“Whoever took my wallet, can you give it back?”

Man, I’ve never heard such a huge explosion of laughter. It wasn’t just the sound; you could feel it. In a single moment fifty thousand people who had been messed up by the earthquake and by months of waiting for help all let go of their tension and their worries and were laughing together. It really was spiritual. With one small line, just a few words, Cantinflas connected with every person in that place. That was a huge lesson to me—the power of laughter.

It also reminded me that in church when I was growing up I saw a painting of people on Judgment Day—those who were damned and going to hell and the other, lucky ones who were going to heaven. I was still a kid: this was supposed to inspire me? I would think, “Keep that to yourself,” and I’d take what little money I had and go to the movies to see Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis acting goofy. I’d laugh my ass off. I’ve always loved comedies and comedians—especially those who know how to make fun of themselves without being racist or vulgar.

Laughter can be a very spiritual thing—if you ask me, I think getting in a good, gut-busting round of laughter is worth more than a month of meditating. It can take you away from yourself, help you let go of a lot of layers of fear and anger. If you get someone laughing, really laughing, you’re dealing with Christ consciousness and Buddha consciousness and divine illumination. To me, Rodney Dangerfield and Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor and George Lopez are all holy men in the way that each of them looks at life and finds a way of making fun of it. It still makes me laugh to think of how Mel Brooks dropped Count Basie and his big band in the middle of the desert in Blazing Saddles and had the black sheriff ride by on his horse with the Gucci saddle—that’s comic and spiritual genius. There’s so much going on in that one moment. Laughter is lightness, and if you don’t have a sense of humor things can get dark really quick.

One of the other lessons to come out of that tour of South America in ’73 was that because I spoke Spanish, I got a lot of practice doing interviews and talking to the audience from the stage. More and more I was stepping in front of the band in public, even though Shrieve and I were still making the decisions together about the music.

Bill Graham produced that first Nicaraguan earthquake relief concert back in January of ’73, and I think that had to be another reason he and I were so compatible. I always believed that music could help people who needed help, and I still do, and in fact that’s how Bill got his start—producing concerts to raise money for the San Francisco Mime Troupe, then to help some people who had been arrested, and the one thing that never changed about him was that he never stopped doing benefits and fund-raisers and putting together concerts for good causes, no matter how big he got. Being around hippies and that San Francisco thing, he couldn’t have ended up any other way—doing what he could to help people and to protest what was wrong.

Remember the S.N.A.C.K. concert Bill put together in 1975 with Bob Dylan and Neil Young and other bands that raised money for after-school programs? Or when he helped raise two million dollars after the ’89 California earthquake with all those rock bands and even Bob Hope? Whenever he called me for stuff like that, I would always say yes—put Santana’s name on the list. In fact, put us on the list first, because I know he could then use our name to get other big names.

Just before Bill died, in ’91, we were talking about an American Indian benefit at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View to mark the anniversary of 1492—“ 500 Years of Surviving Columbus,” we were going to call it. The last phone message he left me was about that project: “Stay well, my friend. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

By the end of ’73, we were all tired of being on the road, and Ray Etzler was our new manager. Bill was still overseeing the business side of Santana, and though we really managed ourselves, we hired Ray to take care of stuff that needed taking care of, like dealing with Columbia Records, which seemed to be less and less in our corner.

Welcome came out that November, and we had wanted our next album to be our concert from Japan. We had heard the tapes of our concerts in Osaka, and they were great—they caught the band at its best, and we were really proud of it. We had a great plan for bringing that music out, for making it an entire Santana concert experience: three LPs, with a booklet and images from Japan, including one of the Buddah, all done by talented Japanese artists. The album included a tune we put together during those concerts and named after Mr. Udo.

It was beautiful and ambitious and the music was fresh, but it was nothing that Columbia could handle. With the album cover and packaging and the three disks, it was just too expensive for them. They didn’t believe it would sell enough. Even after the Japanese finally released Lotus in the summer of 1974 and it became the bestselling import at the time, Columbia wouldn’t budge, and even Bill couldn’t make them. That’s how different things were after Clive was forced to leave. I was learning just how bureaucratic things could be in the United States and how differently record companies were run in Europe and Japan. You know what Columbia did around the time Lotus came out? They put together a single-disk greatest hits album, as if we were some over-the-hill group, and released it around the same time. That was a low point.

We’d pushed so hard to be as good as we were on that album, to deliver hundreds of shows that year, that if you look at the Santana schedule for the first half of 1974, you can tell I was recovering—everyone in the band was. There were a few Santana shows, but most of my energy and intention was focused on meditating and being with Deborah in Queens. I did a few spiritual concerts with Deborah and John and Eve McLaughlin, and sometimes with Alice Coltrane and her group, and sometimes when Sri was there he would start the night and read his poetry.

Hanging around Turiya inspired me to write some spiritual melodies, and when she heard them she surprised me by coming up with some arrangements to go along with them—symphonic oceans of sound, tides flowing in and out. Those first tunes became “Angel of Air/Angel of Water” on the Illuminations album, which was the first album to have my spiritual name on the cover. All the planets aligned to make that one happen: Turiya was in between record companies at the time, and Columbia agreed to it but wasn’t expecting any radio hits, so the attitude was that they’d figure out what to do with it when it was finished. Basically, Columbia told us, “Go and have fun.” The album was like Abraxas—no hassles at all—but the music really took me farther away from that classic Santana sound than almost any other recording—farther away but closer to where my heart was.

We did the sessions at Capitol Studios in Los Angeles, where Frank Sinatra used to record, because Turiya knew it and there was space for a full string section. Everything was done live, and it was amazing to be in the same room with Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland—both of whom had played with Miles—and Armando and Jules Broussard and Tom Coster. There was a great vibe: Armando would tell a story, and we’d crack up, then Turiya would say something that made us all laugh even harder. Everyone thinks of Alice Coltrane as being a serious, deeply spiritual person who was somehow close to the divine and was not allowed to joke around. But she loved to laugh and have fun.

I remember riding with her once in a limousine, and she said, “Carlos, I have to tell you something, but please don’t laugh.”

“Okay, Turiya, I won’t.”

“I want to play you my favorite song now.” She was giggling like a little girl. She put on the track, and it was Ben E. King’s “Supernatural Thing.” I was like, “This is your number one right now? It’s cool—that’s a great tune.” It was great to see that part of her—enjoying music in a pure way, without needing it to be one style or another.

I love the string arrangements on Illuminations and what Turiya played on harp and organ, especially on “Angel of Sunlight,” which, like many of Turiya’s songs, opened with tabla and tamboura; two disciples of Sri Chinmoy played them. I played my solo, and the engineers got an amazing tone on my guitar that I think was partly because of the room but also because the Boogie amplifier I brought with me had a second volume knob, which let me play softly but still with a lot of intensity. There’s a joke that goes, “How do you get a guitar player to turn it down? Put a chart in front of him.” Well, in that session I was tiptoeing, walking on eggshells because of everyone there, so I wasn’t going to blast my guitar, but the Boogie helped me turn it down and still be loud in my own way.

My favorite moment on the whole album came right after I finished that solo. Suddenly Turiya blasted off like a spaceship, playing that Wurlitzer, bending the notes with her knees—she had some gizmo that stuck out of the side of the organ—and Jack and Dave and I all looked at each other like we were hanging on for dear life! It was one of the most intense things I ever heard her play.

It was my idea to get DeJohnette and Holland for the album; Turiya had wanted a young drummer in Los Angeles, Ndugu Chancler. She introduced me to him, and he told me he had played with Herbie, Eddie Harris, and many others. He had a sound that I immediately liked, very much like Tony Williams. In fact, Ndugu had also played with Miles for a little bit. He didn’t play on Illuminations, but I got to hear him play, and I kept his name in my head because I definitely wanted to get together with him at some point. I still do that with musicians I hear and like. I’ll file the name away in my mental Rolodex, and sometimes it will be years later when I think about them and give them a call.

At the start of summer Shrieve and I started working on the sessions that became Borboletta, which I think of as the third part of a trilogy, along with Caravanserai and Welcome. I call them the sound tracks—those three albums were like a set. They all had the same loose, jazzy feel and spiritual mood. The sessions were in May and June, and TC became very important to us in the studio—he would get a production credit with me and Shrieve—and we kept some of the same band as we had on Welcome, with a few changes. Flora Purim and her husband, Airto Moreira, were very important to that album. Leon Patillo—who sang and played keyboards—joined the band, too, and brought a gospel kind of vibe, which was different from what Leon Thomas had brought. We asked Stanley Clarke, who played bass with Return to Forever, to help us out on some tracks, and he did. Dougie left to go work on other projects, such as playing with David Bowie. David Brown came back into the band and played on some of those tracks, too.

They were fun sessions—I was getting used to seeing new faces for each album, and I enjoyed seeing how we reacted when they played with someone new for the first time. There was always going to be someone who would be checking out the other guy, testing him. We were playing “Promise of a Fisherman” when I looked over at Armando and Airto, and they really seemed to be going at it musically, really pushing each other. Airto looked at me as if to say, “What’s with this guy?” Later he asked me, “Is he always that competitive? He has those congas, and all I had was a triangle, but still it felt like he wanted to kick my ass.” I got used to those kinds of surprises.

Another surprise? We were almost done with the new album and getting ready for our first tour in six months when Shrieve got very sick and had to go into the hospital with kidney stones. I called Ndugu—he played on one track for Borboletta because it looked like Shrieve needed more time to recover—and I asked him to come on the road with us.

I could tell immediately that Ndugu was the right choice—he was especially good with a funky backbeat and could still handle the jazzy numbers. A lot of drummers can only do one or the other, and their backbeat can get really stiff and stifling. Ndugu had no rigor mortis—he was open and not suffocating. He was also blessed with knowing how to tell which kind of groove was best and was able to bring the kind of feel that was coming from Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, which helped move Santana toward a ’70s kind of funk. Michael Shrieve was more meshed with Elvin Jones and Jack DeJohnette, and he had his own sense of funk, but it wasn’t as tied into the ’70s as Ndugu’s was. It was just two different ways of playing.

I wasn’t thinking of disengaging Michael Shrieve from the band when he got sick, but that was what happened. I knew we weren’t going to cancel the tour, and I was getting very curious to know how our sound could change and develop in a new direction. So there were those reasons for pushing ahead, and I know they didn’t all sit right with him. We never formally decided that he was going to leave the band, and we never made his departure official or public. When I think about it now, it wasn’t handled ideally or in as gentlemanly a way as it could have been, what with Michael being in the hospital. But the decision to go ahead with the tour was what made us realize that we needed to go our separate ways.

I cannot speak for Michael, but I think the separation gave him a kind of freedom to take time away from touring and explore some different music ideas, because that’s what he did. He’s a super-talented drummer who made music in other bands and for film—to this day he still contributes songs to Santana. He moved to New York City and lived there in the ’70s and ’80s, and I visited him there almost every time I came through. He was always gracious and welcoming—I think we had been through too many of the same things together in music and on our spiritual paths for the sediment of anger and resentment to muddy the water between us.

Shrieve leaving Santana was the band’s final step in its evolution from being a collective to being a group with two leaders to finally being a group in which I alone was in charge. Shrieve was the last connection to the old band, the last person whom I would confer with and sometimes defer to. Chepito was still in Santana, but he still had his own agenda; he was more like a hired sideman in the band, and I think that touring so much in ’73 had kind of distanced him from me and strained the relationship between us, the way it strained us all.

If you want the date that I took on the full-on duties of leading Santana and it really became my band, it would be sometime in late June of ’74. Since then I’ve tried to do my best to be true to the original spirit of the band and to the music. And since then it’s been a blessing and a duty. There has been freedom from having to be responsible to another person, but at the same time there is the everyday responsibility of making decisions and plans, and I am still trying my best to navigate Santana with honesty to a place where it’s all milk and honey.

I was almost twenty-eight then, and when I look back I don’t remember it being difficult—switching to that role of being the leader. I didn’t feel too young or too naive or lacking in experience. We’d already been through the big move that put me and Michael at the helm. I’d say it felt natural: the way I looked at it was that Santana was really me even before there was a Santana band. What was difficult was resisting other people’s interpretations of what they thought Santana was or what it should be, both from outside and within the band. The people closest to me who encouraged me to be myself and to trust myself were Bill Graham, Deborah, and especially Armando. He was the only one inside Santana who was always in my corner with a supreme confidence that was contagious. He’d say, “There’s only one Santana in this band—that’s you, Carlo. You tell them this is your shick now.”

In the middle of the 1970s it felt great to be young and leading one of the most important rock bands on the road. The music and the hits from our first three albums and the Woodstock movie were like a wave of energy that did not stop carrying us through those years. The blessing was that we could be as busy as we wanted to be, even without any new radio hits—though we did have a few more hits in us that would come later in the ’70s.

The other blessing was that we had an inner balance and focus that, for much of the time, kept most of us away from the temptations and excesses of the era. We were starting to have a language with which to deal with the spiritual world and the so-called realities around us. There was a bridge between the seen and unseen realms that was important if we wanted to keep going with our music and stay relevant and connect with the past and continue into the future.

When I think of those years in the ’70s, I think of the many musicians and legends I was able to meet because of where Santana was in the music world. Some were heroes, some were friends, and some were not—and there was always something to learn from all of them.

I remember feeling uncomfortable that Muddy Waters was opening for us. We should have been opening for him, always. His blues music was so important to so many people, and he was the one blues legend I was too intimidated to introduce myself to, even in 1974 and ’75. I loved seeing how he put together his shows—who played first; who came on next. For example, I was wondering why Muddy needed three guitar players in his band. But then in the middle of the show he’d point to one of them, who’d play a solo in B. B. King style. Then Muddy would point to the next guy, who would play a solo in Freddie King style. Finally the last guy, who sounded a little like Albert King, would play. Then Muddy would step up with his slide guitar and just kill it—show everyone who was in charge—and bring the house down.

By the end of the show the audience had their mouths open, wondering how it was possible that this older guy had so much energy and soul. Then Muddy would show them one more time in the encore. He’d say, “Thank you so much. It’s so wonderful to play for y’all. Right now I want to introduce you to a very special person—please give my granddaughter a nice hand!” He would bring out a lady who was in her twenties. Big applause. “Okay, now I want you to give a hand to my daughter.” Of course, everyone was expecting a woman in her fifties, but out came this little six-year-old girl. Everybody would suddenly get it, and with perfect timing Muddy would go, “Now you see I still got my mojo working… one, two, three, hit it!” And he’d go into his last number.

You can’t make this stuff up. I have so much love for the mentality and spirit of that dude.

Here’s another special moment from ’75: the same day I got to meet Bob Dylan for the first time, I got to jam with the Rolling Stones! I was staying at the Plaza Hotel, across from Central Park, and so was Bob. I knew his music from the ’60s, of course, but in the years since then I had really begun to treasure his genius. I remember once sitting down with “Desolation Row,” listening to the words and breaking it down for myself: “Einstein, disguised as Robin Hood / With his memories in a trunk / Passed this way an hour ago / With his friend, a jealous monk.” I mean, this guy is like Charlie Parker or John Coltrane the way his imagination flows—absolutely astonishing.

We were introduced, and we were hanging out in a suite, just getting to know each other, when I got a call that the people from CBS Japan were there. I remembered that I had a meeting with them. They were there to show me the Lotus album, and I asked Bob if he wanted to see it. So the record people came up and started to take the album apart, spreading the artwork out on the floor, unfolding the pages in the book, and it was just an incredible package. I saw Bob’s eyes getting big.

The phone rang again, and this time it was the Rolling Stones’ people—the band was in town playing Madison Square Garden. Did I want to come and jam with them? “Well, I’m here with Bob Dylan.”

“Well, please bring him, too!”

So a little while later we got into a taxi—Bob, my Mesa/Boogie amp with the snakeskin cover, and I. Nobody sent a limo or anything, which was no problem until we arrived at the Garden, told backstage security who we were, and it was obvious they didn’t believe us. I guess they were probably thinking, “Bob Dylan and Carlos Santana together? Showing up in a taxi? Nah.” We called the Rolling Stones’ people, and they came down to get us.

The concert was incredible—I think it was the last night of the band’s run there, and the place was electric. There was an opening act with steel drums, and Billy Preston was hanging out and playing with the Stones, so I got to meet him. They did their show, and near the encore they came up to me and asked me to come on and play on “Sympathy for the Devil.” Mick sang his part, then turned to me, and I put my finger on the string and… wham!

Suddenly I noticed heads turning and eyes looking at me. I don’t know if the band had miked my amp too hot or something, but somehow I don’t think they were ready for the sound of that Boogie amp—the drive and the intensity. I was thinking, “Yeah, that’s how it’s supposed to sound.”

I’m not taking any credit for what happened after that night, but I will say that if anyone remembers the Stones’ next tour, in ’77, it was all Mesa/Boogie amps onstage. And the year after that Dylan played Japan, and they made a nice-looking double album from the concert.

That same summer I finally got to jam with Eric Clapton. When we play together I don’t hear Eric Clapton or Santana. With Eric, it’s a conversation about whom we love most. “Oh, you got some Otis Rush? How about some Muddy Waters?” When we play it isn’t about crossing swords and dueling, which is how some people think of jamming. It isn’t Fernando Lamas versus Errol Flynn. It’s “You got Robert Johnson, and I got Bola Sete.”

I think the best guitarists have the biggest boxes of heroes—some British cats tend to limit themselves to one kind of style, but not Clapton and Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. They listen to Moroccan and African music—recently Jeff Beck has been checking out Romanian choirs. George Harrison listened to Indian sitar. I think Stevie Ray Vaughan could be fearless when it came to listening: he didn’t just check out T-Bone Walker, he also checked out Kenny Burrell and Grant Green and Wes Montgomery. It wouldn’t be fair to call Stevie a blues guitarist. You can hear it on “Riviera Paradise”: his vocabulary went far, far beyond Albert King. All these guys I mentioned are open to many influences, but they’ll always be rooted in a certain thing. Each musician to me is like an airport—there are a number of different planes coming in and landing and leaving. It’s never just one airline.

It’s always changing—right now I want to hear some Manitas de Plata, because he’s blues and flamenco together. I want some of Kenny Burrell’s Guitar Forms with Gil Evans arranging and Elvin Jones on drums—I could live with that on a desert island forever. As much as I love John Lee Hooker, sometimes I have to say, “Hold that thought: I’ll be right back. I got to hang out with some elegance and ‘Las Vegas Tango.’”

I noticed later that all the heavy metal guys—at least those who play very fast, like Eddie Van Halen and Joe Satriani—remind me of Frank Zappa’s kind of fearlessness, which leans toward a Paganini vibe as opposed to a B. B. King or Eric Clapton vibe. A blues connection might not be there anymore, but that’s not good or bad; there’s a nice contrast to all of it. It’s just a matter of apples and oranges and pears and bananas. Santana’s not going to be everybody’s favorite music every time.

“You’re not made out of gold”—that was my mom talking.

“Oh, yeah? What’s that mean?”

“Not everyone’s going to like you. You can’t be everyone’s golden boy.”

She was right. That was another lesson I learned a few years later. In 1980 we played a double bill in Cologne, Germany, with Frank Zappa—two shows, one that he opened and we closed, and the other that we opened and he closed. I wasn’t thinking that this would be another situation like the ones we had with Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Wilson Pickett, but when I went to Frank’s room to say thanks for the music, I could tell that he was someone who wasn’t going to let me into his awareness. I don’t remember what he said, but I got a feeling that I wasn’t supposed to be there.

I quickly offered my respect and gratitude for his music and left. I was sincere—I liked his music, especially “Help, I’m a Rock” on Freak Out! and that raw and dirty blues, “Directly from My Heart to You,” on Weasels Ripped My Flesh. Whatever it was Frank didn’t like, it came out a few years later when he made “Variations on the Carlos Santana Secret Chord Progression,” and in one listen I knew it was not a compliment. But in a weird way it was like a compliment because he went out of his way and spent time and energy to make a point about my music. You know how I found out about it? I was still buying Frank’s albums even after we met back in ’77. I loved the title Shut Up ’n Play Yer Guitar, so I got the album, and there it was.

My answer to anyone who’s so invested in that kind of criticizing or hating or toxic feelings has never changed over the years. My phone would ring, and it would be Miles or Otis Rush. Today the phone still rings, and it’s Wayne Shorter or Buddy Guy. Do I care what you think about me?

By ’75, there had been many calls from Miles, especially when I was in New York City. One time back in ’71, Miles called me at my hotel in New York and got me to come down to a weird gig at the Bitter End. “Write down this address. I want you to come over and bring your guitar.”

“Okay, Miles,” I said. I went down there but left the guitar behind. When I got there Miles was screaming at the owner of the club—screaming with that hoarse voice of his. In the middle of all that cussing he suddenly turned to me and got all nice, like, “Hey, Carlos, how you doin’? Thanks for coming by.” Then he turned back to the owner and resumed the yelling and foul language.

Richard Pryor had just started his set—he was the opener, and he was cracking everybody up. Then Miles said, “Where’s your guitar?” I just shrugged my shoulders. “Oh, I see.” I didn’t say anything, but this was the band with Jack and Keith and Michael Henderson on bass. The way those guys were scrambling things, I couldn’t even find 1. They started playing, but Miles was still pissed at the owner, and it was like he went on strike. He stood his trumpet on the floor and then just lay down—right there in front of the stage—while the band was working on colors, not really songs.

Whatever needed to happen must have gotten worked out, because eventually Miles got up, put the trumpet to his mouth, and everything fell together. Suddenly there was a theme and a focus and a feeling of structure. It was amazing—he changed the music without even playing a note.

I think Wayne and Herbie would agree that a lot of what made them the way they are today was because of being with Miles. I think it was like that with anyone who played with Miles—even to this day Keith Jarrett, Chick Corea, Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland, Gary Bartz, and many others are all making music that is the best in jazz, making music that makes other stuff sound like easy listening. I remember Branford Marsalis talking about this after he played on Miles’s Decoy album. He said that with Miles he was able to play stuff he had never thought about playing, but as soon as he got back on the road with his own band he was playing the same old way as before. He credited Miles for bringing new things out of him.

I know how Branford felt, because Miles’s consciousness permeates many musicians, not just those who played with him. It permeated me even before I heard him live, just from listening to his albums and reading the liner notes and playing along with John McLaughlin on In a Silent Way. You know, Miles never really came out and asked me, but I sometimes got the feeling he was checking to see if maybe I would be in his band. He’d ask, “So you like living in Frisco?” It was the closest he came to inviting me, but then my stomach would tighten up and I’d say to myself, “No, don’t do it. It will break up a friendship.” With Miles I knew enough not to get too close. Also it was an honor to think that it was even possible, but I never thought I’d be able to hang with the music he was making then.

The other thing about Miles was that you couldn’t rely on knowing what he had done in the past. That can be intimidating. He was moving forward with his music and not looking back. I only remember one time that he changed his mind, just for a moment. Miles was at the Keystone Korner in ’75, and his band started with some deep funk stuff. Miles was playing organ; his trumpet wasn’t even out of its beautiful leather case. The music sounded like a freaking cat in the alley, with a subwoofer that only gophers could hear, way down there. I was thinking, “Oh shit, that’s the opening song?” All of a sudden a big lady in front yelled out, “Miles! Miles! Play your trumpet!”

The whole place was looking at her, and her date was trying to hush her up, but she wasn’t having any of that. “What? I paid for your goddamn ticket, and I paid for mine, too. Miles, play your goddamn trumpet! We don’t want to hear this shit.”

It was on Miles what to do next. He looked at her, then opened the case, took out the trumpet, and brought down the band. Then he got down on one knee right in front of her and gave her a little taste of Sketches of Spain. Only a woman could have gotten away with that, and I loved the way Miles handled it.

At that time I was starting to see a few things about Sri that weren’t endearing him to me. He was still treating me with favoritism, but sometimes he’d say things that didn’t feel right. I didn’t feel that a holy man should complain about his disciples and be ragging on their imperfections. My feeling was that as disciples we were supposed to be the ones who were human, who needed inner work, and he was supposed to be the one showing us how to be compassionate.

My pulling away from Sri was gradual but efficient and tangible, because for me, everything that used to be honey was turning to vinegar. By ’77 it felt like it was time for me to go. Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin had both left by then, but Deborah wanted to stay. I was starting a long tour with Santana at the beginning of that year, and that’s when I told her I was leaving him. “You can stay with Sri if you want, but I’m gone.”

The Santana tour in the first half of ’77 went on for months and months. I was disconnected and cut off from my life in many ways. Deborah and I were on the same frequency when I left, and I felt our spiritual paths should be together whether Sri was guiding us or not.

But when that long tour came to an end in April I could tell it was time to come home and be with Deborah, or we were done. We got together, and she got very, very serious, and I knew what I had to do to not lose her. I asked Bill to come by our house in Marin. He had booked Santana to do some dates at Radio City Music Hall—after a sold-out US tour, this was going to be the crowning jewel of those four months. I recognized and respected that. I knew what I was risking, but I told Bill, “I can’t make those gigs, man. I need to spend time and reconcile things with Deborah and heal the situation. It has to be now, right away.”

The first thing Bill said was, “Carlos, you must be out of your mind. Those tickets are already on sale!” I said, “Well, I probably am out of my mind, but I feel that right now this is what’s supremely important to me, and there’s nothing that can change my mind.” I put it in words I knew he’d understand. “The Santana machine is not more important than my relationship with Deborah.” Bill looked at me, and in his face I could see him slowly go through a full mix of emotions—anger, hurt, frustration, and finally defeat and deep sadness. Then he said, “Carlos, I hope that someday in life I will know love like this.”