CHAPTER 18

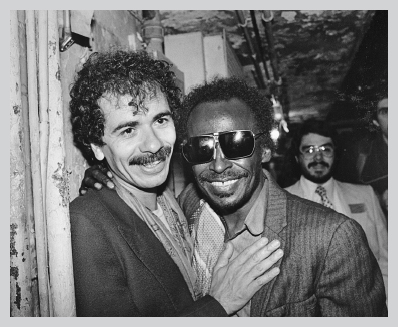

Miles Davis and me at the Savoy, New York City, May 5, 1981.

In the ’80s Santana could tour just as much as we wanted. We navigated across the country, playing the same venues in the same cities, from Detroit to Chicago to Cleveland to the usual places in the New York area—Nassau Coliseum, Jones Beach. You could hear us on classic rock and oldies radio stations. I’m proud that those songs kept good guitar playing out there for many years, even when there were few guitar solos on popular songs. You could hear oldies on the elevator or at Starbucks with a solo by Eric Clapton or Jimmy Page, and sometimes the solo itself was more memorable than the song.

One of the best compliments I got after Supernatural was from Prince. He said, “Carlos, because of you I can play a guitar solo on one of my songs and it’ll be on the radio.” I had never thought of that. I replied, “Yeah, it wasn’t cool to have guitar solos on songs for a while.”

In the ’80s, radio wasn’t making or breaking Santana. I think our reputation was always more about our shows, because people need to be given chills. When you get chills you immediately become present in the now. And because of that our audiences can feel that the intention and purpose of the band is a whole lot more than entertainment. It’s to remind everyone on a molecular level of their own significance, to convey the idea that each of us has the power to bring forward abundance from the universe right now. Santana is a live experience, bringing the moment more than the memory. That will never change.

In 1981 it was time for a new start and a new home—a family home. Deborah and I left the East Coast and moved from Marin County to Santa Cruz. It was the first house we bought together since we had met, and right after that her parents and my parents came to visit. We started to spend more time with our friends, and Carabello and I reunited because he had married Mimi Sanchez, who was still one of Deborah’s best friends. They started coming to the house a lot. We were both older and smarter by then.

Watching Carabello grow to become a proud man who is positive and honorable has been gratifying to see, because I want people to understand that we need to believe in each other. It makes us stronger than we are by ourselves, and it can make us change. There’s always someone in every neighborhood who in the end redeems himself. In my neighborhood it was Carabello—we have so much history between us, which goes back to my Mission High days, and I’m very pleased about that.

Just as I did, Carabello remained friends with Miles—he stayed at Miles’s town house when he visited New York City. In ’81 Miles was coming back after he had stopped playing in ’76. Nobody had heard from him for around five years. All the stories said that he was in a dark place with the curtains closed. I sent him cards and flowers once in a while, and I heard through Herbie and Dave Rubinson about him because they used to visit him. I know he thought of me, and I thought of him.

Santana played Buffalo that year, and as we were getting ready to come to New York City to play the Savoy we were listening to some Miles. I remember Rashiki asking if I thought Miles would ever put the trumpet to his lips and play again. We still didn’t know. I said, “Nothing is really impossible—maybe when he gets bored.”

Sure enough, a few days later, when we got to New York, I heard Carabello was coming to our show at the Savoy and bringing Miles. I couldn’t believe it. We finished doing the sound check, and there they were backstage. Miles had on a suit that made him look a little raggedy, like he was living a funky life.

It didn’t matter. Man, it was beautiful to see him. Bill Graham was producing that tour and got as excited as a kid. “Miles, it’s so great to see you! Thanks for coming out. How are you doing? How do you feel?”

Miles seemed to think Bill was checking up on him. “What?” he said.

“How do you feel, man?”

Miles said, “Put your hand up like this.” Bill put his hand up, and Miles punched it real hard—a Sugar Ray Robinson jab, up close and hard. “I feels fine, Jewboy.” Same old Miles.

I went to my room to meditate, as I do before I go onstage, and Miles followed me. I told him what I had to do, and I closed my eyes and started getting quiet and going inside. I wanted to do that for at least ten or fifteen minutes. Miles was very respectful—he didn’t talk, but I could feel his eyes, like two lasers, focusing on the medallion I was wearing. I could hear him breathe, and I opened my eyes. He was looking at the medallion like he was going to pierce it with his gaze, so I said, “Miles, do you want it?” He said, “Only if you put it on me.” I took it off, put it on him, and he said, “I pray, too, you know.”

“You pray, Miles?”

“Of course. When I want to score some cocaine I’ll say, ‘God, please make that motherfucker be home.’”

I was like, “Oh, dang!”

There’s a thing I used to do whenever we played and Miles was near—I still do it when we’re in New York City. I’ll play a little bit of “Will o’ the Wisp” from Sketches of Spain. We played it in the concert at the Savoy, and after the show Miles mentioned it for the first time. “Yeah, I like the way you play that. A lot of people don’t know how to do it right.” I said, “Miles, we got a limousine. Would you like us to take you home?” So five of us got into the limo—Miles, Carabello, saxophone player Bill Evans, Rashiki, and I. When Carabello got in the front he slid the seat back, which hit Miles on his foot, which was already hurting for some reason. Miles got real brutal, and he immediately went off on Carabello.

We started driving around, then suddenly Miles turned to me and said, “Carlos, this Puerto Rican bitch tried to get some cortisone in me to help me with this thing I have with my foot. She was saying, ‘Cortisone this, cortisone that.’” I thought about it and laughed. “Miles, she’s saying corazón—that means ‘sweetheart.’ She loves you.”

God loves characters, and God loves Miles. That whole night was incredible, crazy. It felt like we had fallen into someone else’s weird version of Wonderland—like we had slipped down a rabbit hole into some other dark, scary world. Miles was telling us where to go. He was in charge, and everywhere we went you could see that people knew him well. Whether they were happy to see him was another thing. He’d try to get away with a lot of stuff—testing people, doing his street act.

Miles took us to one of those nightclubs that looked like it had come out of Escape from New York. It had steel shutters everywhere. We got out of the limo, and I was wondering why we were there, because it looked like an abandoned factory. Then a big security guard carrying a baseball bat came up to us. He said to me, “You guys are all right. I know who you are.” Then he pointed to Miles and said, “Why do you have to bring him here?” Miles walked right past him into the dingy building, and I just followed.

Miles went straight to the piano, which was beat up and out of tune. He said to me, “Come here—I want to show you something.”

I said, “Okay,” and went over to him. Miles looked at the keyboard and stretched those long fingers of his. Man, you could do a whole movie just on Miles’s hands. He was doing the same thing Wayne does at the piano—look, wait, then pounce. It’s funny—my wife eats that way: Cindy with food, Wayne and Miles with chords. That night, when Miles hit the chord, the whole club just disappeared—suddenly I was in Spain, in a castle in an old adventure movie. Miles said, “Do you hear it?”

I said, “Of course—that’s incredible. Thank you.” He got ready to show me something else, but some guy got up and put a quarter in the jukebox, and the song “Muscles” by Diana Ross came on, totally changing the mood. Miles looked over at the guy, who knew what he had done, because he was looking back. Miles stared at him some more and then said, “Man, you know who I am?” He said, “You’re Miles Davis. Big deal.” Just like that. That was all Miles needed to hear. He smiled and went up to the bar. “Give me a fucking rum and Coke. And whatever he wants.”

Miles started to get bored with the place, so we all got back in the limo, and Miles said, “Carlos, are you hungry?”

“Yeah, I could eat something.”

“I know a great place where they have black bean soup.” So he told the driver where to go, and we got to talking. Suddenly Miles looked up and saw that we’d driven too far. This was through his sunglasses and the tinted windows and all that. He opened the partition behind the driver and shouted, “Hey! You passed it—it’s two blocks back. Back up the car!” The driver said, “I can’t go back: it’s a one-way street.” Slap! Miles reached through the little window and whacked him on the back of his head! “I’m telling you—go back!”

So we backed up the narrow New York street and went into the restaurant, another funky place. We found a table, and Miles said, “I’ll be right back; I got to go pee.” On the way to the men’s room he saw a woman and stopped and started talking to her and then whispered in her ear. When he was gone, she turned to me and said, “You’re a nice man. Why are you hanging around this filthy-mouthed guy?”

While Miles was in the bathroom, the soup arrived, and a big, burly waiter with huge arms came over and said, “Hey, Santana, want some bread with that soup?”

“No thanks—I’m cool. Just the soup.” But when Miles came back he didn’t see a bread basket, so he told the guy to come over. “Hey, motherfucker, where’s the bread?” The waiter looked at Miles and put his big arm on the table right next to Miles’s face and said, “Man, what did you just call me?”

This is the part that was like Alien vs. Predator. Miles had some really long fingernails, so he put his beautiful black hand around the guy’s arm really slowly, looked up at him, and in a really creepy way said, “I’ll scratch you.” The guy shook his head and kind of slithered away. Rashiki and I were looking at each other like, “Man, this is some scary shit.”

A whole night with Miles in New York—it was really challenging sometimes to be with that dude. That night ended when the sun was starting to come up and Miles took us with him to score some coke. We drove to a neighborhood where I didn’t want to get out of the limo, so I told him that I had to get back to the hotel because we had an early flight later that morning. Rashiki and I stayed in the limo—I took some money out of my wallet and gave it to Carabello and said, “Here’s some cab money for you and Bill Evans.” I waved good-bye to Miles, but he was already walking away into the dawn, getting smaller and smaller.

I remember thinking he seemed like a kid walking through Toys“R”Us who knows he can pick out anything he wants. Everybody in New York knew him. He had carte blanche—he was Miles Davis.

I saw Miles again later that year in New York City when he played Avery Fisher Hall. He came right up to me and gave me a hug, which was the first of only two times he did that. I really cherished those moments—I didn’t see him hug many people. At Avery Fisher it was the strangest hug—he locked his hands behind my head and put his nose to mine, so we’re looking straight into each other’s eyes, then he picked himself up from the ground while holding on to my neck. So he was hanging from me, and he looked at me and said, “Carlos, it means so much that you’re here.”

The second time Miles hugged me was at his sixtieth birthday party in 1986, on a yacht that was docked at a marina in Malibu. I felt so moved afterward that when he went to greet somebody else I went off the boat just to take a moment. I was looking at the ripples in the water when his nephew, Vince Wilburn, came over, and I said, “Man, it really affects me when he greets me like that.” He said, “I saw that. Right after you left he said, ‘That’s a bad motherfucker right there.’”

It’s something to be validated by a giant like that—a giant who was a divine rascal, too. I remember he was an hour and a half late to his own party that day, and while we were waiting I was talking with Tony Williams, who was smoking a cigar next to the boat, and he told me, “This isn’t the first time he’s done that.”

Zebop was the album I made when I started playing a Paul Reed Smith guitar—which would become my main guitar. Paul is still my main guitar maker to this day. He and Randy the Boogie Man have given birth to creations that have done so much for guitarists and pushed the boundaries of excellence, each in his own way—Paul with his guitars and Randy with those Boogie amplifiers.

Paul Reed Smith—I like his heart and the people he hires. His workshop is like the set of a science fiction movie. More science than fiction. From the carving to the measuring to the fine-tuning to the varnishing, he knows the science of it and how to get the balance right so the guitar has—here’s the word: consistency. No matter the weather or the place or the circumstances, a PRS guitar will not fail you, because it behaves itself. One other thing: whenever Paul ships them, the guitars always come out of the case in tune. It’s a personal touch.

The funny thing is that when I first fell in love with two of those PRS guitars, they were the prototypes. I had models 1 and 3, but meanwhile Paul had moved on and redesigned his guitars and was manufacturing them. It wasn’t just the shape—the new model of what I had been playing sounded different to me, a little more nasal. I asked Paul to go back to the old style, but he said it was cost-prohibitive at that point to redo the guitar. My argument was that I know what happens when somebody sees Tony Williams playing a Gretsch or Jimi Hendrix with a Stratocaster or Wes Montgomery with a wide-body guitar. I just knew if kids could see me with that guitar they’d want the same thing—and I knew there would be enough of those kids to make it work on the business side. I had a feeling about product endorsements—my name could sell things besides albums and concert tickets.

Around 1989 some of my guitars got stolen, including those original PRSs—we had someone in our organization who trusted somebody he shouldn’t have to store some equipment he shouldn’t have stored. We did a big APB campaign to get them back, and by the grace of God we found them in hock somewhere because they were so unique. The happy ending of that story is that we found the guitars, and Paul decided to use the original mold to make some new guitars in the old style, and now we’ve had a long relationship and PRS has my endorsement.

I have learned about the value of product endorsements and have also learned to trust my first instincts about some things. Here’s another example: like Paul Reed Smith, I will always have affection for Alexander Dumble and his amplifiers and of course for Randy the Boogie Man and his Boogie amps. In 2013, Adam Fells, who works in our office, sent me a video that the people at Sony Music had found of Santana in Budokan in ’73. I watched it and heard the guitar sound and looked closely at the amplifier and it hit me—“That’s my old friend. I miss that sound!” It was Randy’s original snakeskin Boogie amp that I had long ago moved on from and hadn’t thought about in years. “Adam, you guys got to find me one of those snakeskin Boogies!” He told me, “We still have them—we haven’t seen them in a while, but they’re in the warehouse.” Adam found them, then Randy fixed them up and worked on the contacts, and I plugged in—and there was that voice. That’s what I’m playing now, along with a Dumble, and I’m getting the best from both.

The point is that after this Randy went back to that old model and design, too. He made more than seven hundred snakeskin Boogie amplifiers. Then he and I signed them, and now everybody wants them. They’re selling like crazy in Japan. So please don’t tell me about something being cost-prohibitive.

By 1981, it felt like the spirit of the ’60s had left America and gone overseas—that was the year Santana played the Live under the Sky festival in Japan, an event that put rock and jazz together. Santana played, Herbie Hancock’s V.S.O.P. band played, and then we played together, along with Herbie and Tony Williams. The old Fillmore Auditorium spirit was alive again—there, anyway.

At that point, when everything in America got so big and was sounding the same to me, I felt free enough with Bill Graham to express myself and call him on what was happening in the music business. If he could walk around with a clipboard taking notes on my show and critiquing me—well, it goes both ways. At least we had that kind of relationship. So I asked him, “What happened to you, man?”

“What do you mean, what happened to me?”

“You used to put Miles Davis and Buddy Rich and Charles Lloyd on the bill with rock acts. You used to stretch everyone’s consciousness and show us all that there was great music out there that was not just what we heard on the radio. But now you’ve stopped.”

He looked down. “Good point.” He had stopped doing concerts in ballrooms and theaters and had started packaging stars such as Peter Frampton.

“I’m sorry,” I said to him, “but why are there no more jazz musicians on the bill?” It was still possible to make that Fillmore spirit happen again—that was my message to Bill. Yes, I know—the business had changed. But it was Bill who had built the business and set the example, and he still had the power.

I’m proud of all the albums Santana recorded in the 1980s and ’90s. Each of those records captured a moment in time; they’re like snapshots of where I was and what I was listening to at the time. They each had an identifiable spirit. With each Santana album I had learned to be present with openness—to listen a lot and be open to not only the musicians and the music itself but also to the producers, because Santana is like the Raiders or the Seahawks—a team. Maybe I’m in charge, but Santana is a collective vision and includes many spirits and hearts and aspirations. We’re going to have to carry that music out of the studio, take it on the road, and play it night after night—maybe not all of it, but you never know until you see how the songs feel and how they are received after the album comes out.

When I did my own albums, my only responsibility was to myself—it was just my vision. In ’82, I made Havana Moon on my own as Carlos Santana, with Jerry Wexler producing. The album started from the idea that Chuck Berry wrote the title song, which is part of the architecture of rock and roll, by pulling from T-Bone Walker and Nat King Cole, especially Nat’s “Calypso Blues,” which had Nat, accompanied only by a conga player, singing as if he had been born in Jamaica. My dad got to play and sing on Havana Moon, and we recorded my mom’s favorite song, “Vereda Tropical.” I also got to collaborate with the fabulous organist and arranger Booker T. Jones as well as one of my favorite vocalists, Willie Nelson.

The songwriter Greg Brown wrote a song that Willie was going to sing called “They All Went to Mexico,” and when I heard the lyric “I guess he went to Mexico,” I thought, “Whoa: this is like something that Roy Rogers or Gene Autry used to sing; it’s like Wayne Shorter’s quotations from ‘South of the Border’ in his solos.” Then it dawned on me that most of my friends saw something about Mexico that was different from what I saw. But I was still a little too close to it all. I grew up in Tijuana, so a lot about Mexico was not necessarily all that groovy for me. But others see something good in the country, and I was trying to see that and see myself in a different light, too. I also started thinking that Willie is from Texas, and that used to be Mexico, so really Mexico is part of his roots, too. Then I thought, “It all connects—we are all part of it. Let’s do this song.”

I have Willie Nelson to thank for helping push me with that tune. Two years later, after Deborah and I were blessed with Salvador, I went to visit Mexico on my own, and the real reconnection began.

As a result of Havana Moon I also discovered Jimmie Vaughan, whose playing I just loved. Jimmie and his band, the Fabulous Thunderbirds, could play shuffles like nobody else, and Jimmie had that Lightnin’ Hopkins and Kenny Burrell thing down to perfection. We bonded right away, and he kept telling me, “Wait until you hear my brother.”

When I met Stevie Ray Vaughan for the first time in 1983, he had a little bit of an edge to him. He tried to challenge me: “Here’s my guitar; show me something.” Show you something? I looked him straight in the eye and told him to put the guns back in the holster. “I love your brother, I love you, and I love what you guys love. Let’s start with that.” He stopped right away and apologized: “Sorry, sir.” I told him he didn’t have to call me sir, but don’t come at me like that.

As I had with Jimmie, I had a profound connection with Stevie from the start—both of us had an incredible, deep devotion to the music we call the blues. When I say “deep,” I mean from the center of the heart. Stevie Ray knew that, and you could hear it in his music, the same way you could hear it in the music of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, and Peter Green before him. Now there are people like Gary Clark Jr. and Derek Trucks and Susan Tedeschi and Doyle Bramhall II and Warren Haynes, along with many others, who keep the flame burning.

The thing that was so different about Stevie Ray is that he wasn’t playing just the flavor of the blues, as many others were at that time. Maybe you can do that with some kinds of music, such as “lite rock” or “soft rock” or “smooth jazz,” but not with the blues. For it to ring true, you got to be all the way in it. Believe me, Stevie Ray was all the way in it. Man, I miss him.

In the fall of ’82 Deborah and I went to Hawaii, and our parents came along, too. One day in front of everyone, my mom told Deborah, “I had a dream that you were pregnant.” I remember my dad jumped on her for saying that, for saying that out loud in front of everyone and putting her on the spot. My mom said, “What? I can’t tell someone about a dream I had?” Mexican moms take their dreams seriously—I guess that’s where I get that.

It turned out that Deborah was already two months pregnant—she asked me how my mother could tell. “She was pregnant eleven times—she knows.” The following May, when I was home from a long tour of Europe, Salvador was born. Just like that you become a parent.

I believe Salvador was a culmination of many, many years of praying by both of our moms. He also came from divine design. Deborah and I would meditate and ask for a special soul to be selected, and then we each took a shower, and we got together. Salvador was conceived with divine intentionality. So were all our children.

Years later I told Sal how he came to be—a few times—and the older he got the more he understood. The first time was when he was just five or six years old and going to public school. Deborah and I knew we could afford to send him to private school, but we wanted him to have a full experience of cultures and people and not be separated by privilege. Sal was very smart—he understood what we were trying to do, and he was okay with that. When he didn’t understand something, he would ask questions.

I came home one day, and Deborah told me, “Your son wants to talk to you,” which was code for “This isn’t going to be a piece of cake.” He had heard some rough words at school—one in particular—and he could tell it was wrong for some reason and didn’t want to talk about it with his mom. I asked Salvador what word it was. “It sounded like ‘duck,’ but it started with an f.”

I was proud of Sal for figuring out a way to say the word without saying it. I explained to him that it was a bad word for something that could be very good, and that something was part of why he was here. I said, “Your mother and I—we prayed for you, we lit a candle, we meditated, we asked for your soul, and then we got in bed and we made love and that’s how you got here. You were made in love. That’s the opposite of that word.” I remember Sal looked at me with his head to one side. “Oh, okay. Thanks, Dad.”

Then he thought for a second. “But what’s it mean?”

“You’ll really have to find that out for yourself when you’re old enough, son.”

Three times it happened—and it was almost always the same thing. Deborah got to the hospital first, and I would get there and see my parents and in-laws waiting. Then the nurse would come with the baby wrapped in a blanket, and we’d all crowd around to get a peek. The first thing we’d see would be the eyes, sparkling just like diamonds. All our children—Salvador in ’83, Stella in ’85, and Angelica in ’89—were born with their eyes open. They were so pristine—we’d all look at Deborah and go, “Good job, Mom.” Then each time I would need to go to the car and suck up some fresh air because the experience was so intense. I’d be alone, sitting there quietly, and slowly I’d start to hear a song.

Every child brings a song with him or her. It’s up to the parent to hear it and get a tape recorder or a pen or something and get it down. “Blues for Salvador,” “Bella” for Stella, and “Angelica Faith”—each one of our kids has a special song, whether it was written for them when they were born or it came later. You look at the child and you just hear the melody. Probably some of my best melodies fell into the couch and got lost while I was sitting there making up a song to sing to the babies—to stop their crying and get them to sleep again.

At three in the morning, when the baby can’t stop crying and his mother is already spent and out like a light—just gone—it’s your turn. So I learned how to hold the babies, strong and secure, tummy-down, and they’d relax. It would get them out of the crying mode. We had a clown doll that you could knock down but it always sprang back up. I hit it by accident one time, and the baby stopped crying, looking to see what happened. We turned it into a game, and it worked almost all the time, at least to break the crying rhythm. There are things any parent can do to be creative with silly stuff lying around at home.

Even before Sal was born, Deborah and I agreed that once he arrived I would never go on the road for more than four weeks—five weeks at the most. Five weeks and home, no exceptions. This was family time. Maybe I could do some recording, but only in San Francisco, and we kept to that. This way I did not miss birthdays or graduations. We have a lot of family videos that I am in—I’m very proud of that.

Sal was only a few months old when we took him to Japan in the summer of ’83, and he was pretty happy his first time over there. He was a big boy, a butterball, for his first few years. He looked like a sumo wrestler. Mr. Udo was helpful, but for Deborah and me it was a wake-up call because of all the crazy hours and the fact that we got sick for a few days. Then we thought about all the germs we could catch by traveling on a plane. Rookie parent stuff. We said, “Let’s not do this anymore.” But when our next two children were born, we still took them with us as much as possible until they started school. I wanted them to see their dad at work, to know what he did when I couldn’t be at home with them—I wanted them to see the world.

I was amazed, but I shouldn’t have been surprised. As soon as the kids came, so did the family. My mom came around, and my sisters and brothers would help out, and Deborah of course had the support of her mother and father and sister, whom the kids loved. They would yell “Auntie Kitsaun” every time they saw her. Not long after Stella was born, we decided to move back to Marin County to be nearer to family and friends. We also had to think about schools. All this pulled me closer to my parents and got me thinking about the fact that my son was part of their legacy.

In 1985 Salvador was almost three, and Deborah and I visited Mexico incognito—my hair was still pretty short, so no one recognized me. I have to say that one of life’s greatest luxuries is to be anonymous in a crowd. Most people should take that to heart. We had decided to go with my mother to visit her relatives in Cihuatlán, so because we were in Jalisco anyway we made a snap decision to visit my hometown of Autlán. We had a driver, but for some reason it took most of the day to get there—four hours there and six hours back.

We met a lot of people who remembered my mom. I was still a kid when I left. Sal was still just a baby but was starting to grow, and he had big feet then. He still does—size 15, bigger than Michael Jordan’s. I know that because when he was a teenager Sal got to spend some time at Michael’s summer basketball camp. It’s crazy sometimes the details I remember.

The whole town was passing Sal around as if he was the first baby they’d ever seen, to the point where Deborah and I were getting paranoid. “Hey, where’s our baby?”

Autlán was so much smaller than I remembered, which of course is normal because I was much smaller the last time I had been there. It felt like what it was—a small town, or a big village. I started kissing my mom on her forehead, kissing her hands. It was in that moment that I began to see clearly what she had done for us. I was thanking her for taking us out of that town and to a place that had bigger opportunities and better possibilities. This is not a put-down or a negative comment about Autlán. I’ve gotten to know the town again, and I’m proud to call it my original home. This is about the immensity of my mother’s conviction in taking us to a place so far away and changing the destiny of our whole family—all because of just one decision in her mind.