CHAPTER 20

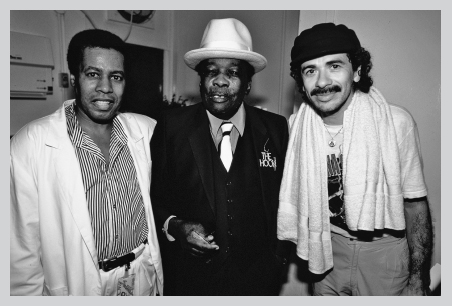

Wayne Shorter, John Lee Hooker, and me, backstage at the Fillmore, June 15, 1988.

Maybe it looks like I’ll record with anybody, especially after Supernatural —“Carlos the Collaborator.” And maybe I still have a lot of spiritual books to read, because I’m supposed to see the same thing in everybody, but in music I don’t, and I won’t. There are some songs that even if you put them into me intravenously my body’s not going to let them go in. It’s like, “Thanks for asking me to play on this tune—I mean, thank you for inviting me, but I don’t hear myself in that.” I’ve said no to certain musicians because quite frankly I don’t like their music. I’m actually surprised they would even invite me. It’s never been about money at this point: it’s mainly about whether I’ll like a song ten years from now.

In the ’80s I recorded on albums by McCoy Tyner and Stanley Clarke and my old friend Gregg Rolie and Jim Capaldi from Traffic. In ’85 Clive Davis asked me to play with Aretha Franklin, which was perfect because I was working with Narada Michael Walden at the time, and so was she. She is the queen of soul. I could not say no to her. Or to Gladys, Dionne, or Patti, but I did once say no to another R & B singer because her version of “Oye Como Va” was a little too LA slick for me. I know she was disappointed, because I had told her that I would do it.

It would be a privilege to do something with Willie Nelson again or Merle Haggard. Anybody in the Coltrane family of musicians I would say yes to, and I would say yes to almost everybody in the Miles family. I said no to a West Coast rapper because the song he sent sounded corny and plastic. I can still hear myself with Lou Rawls.

These days collaborations don’t happen in the studio—they’re just files e-mailed between engineers. I’ve adjusted to that. I’m lucky because I was born with a highly active imagination. I can close my eyes and you can grab a Sam Cooke song and I can play on it as if he were next to me and I can say, “It’s an honor to work with you, Mr. Sam Cooke.” Imagination gets past time and distance and separation, which is what any collaboration has to do, too. Imagination is like, “I’m right here, and you’re right here, and let’s get it on.”

Prince is a bad dude, a giant dude. It would be an honor to do something with him from scratch. I have the songs that would work for us. He’s a hell of a guitar player, a hell of a rhythm guitar player, and he’s sat in with Santana a few times. I’ve heard him play piano, and sometimes he goes into a Herbie place. He’s a genius genius. The only thing is, we’d have to find common ground—swamp–African–John Lee Hooker stuff—so it doesn’t get slick-a-roni. I like it down and dirty and barefootin’, and I think that’s what he loves about the music, too. We got to go to the jungle, man.

The best-paying jazz gigs today are usually the festivals, and many of them take place in the summer. The winter before the summer of ’88 I asked Wayne Shorter if I could start a rumor. “A rumor about what?”

“That you and I are in a band going on the road.”

He smiled with a twinkle in his eye, as he often does, and said right away, “Yes, you may.”

Wayne and I brought together a group that we thought was perfect for both of us: there were two keyboardists—Patrice Rushen, who brought an element of Herbie Hancock, and CT, who brought elements of Joe Zawinul, the church, and some McCoy. Plus we had Alphonso, Ndugu, Chepito, and Armando. We split the set list between some songs Santana usually played and Wayne’s originals. I asked him if he would mind doing “Sanctuary” in a boogie way. I think I got a couple of dirty looks from somebody in the band, but Wayne smiled and said, “Yeah, let’s do it”—and he took that song back to his early days in Newark.

We did twenty-nine concerts together, and we should have called it the Let’s Do It tour—it was fun and different every night. I think Wayne could feel that there was a camaraderie in the group. I’m glad Claude Nobs helped us record our performance in Montreux. We did a concert at the Royal Festival Hall in London. Backstage before we went on, Wayne, Armando, Ndugu, and I were hanging with Greg Phillinganes and a few guys from the Michael Jackson tour, which was in London at the same time. John Lee Hooker, the original Crawling King Snake, was also in London, and he came by. I called it Hanging with Some Heavy Hitters. I couldn’t have been happier than I was that night.

Playing with Wayne taught me how he goes into a melody. It’s like a blind man checking out a room for the first time, or like a dancer trying out a stage so he can memorize it. He purposely plays almost as if he doesn’t know how to play, with a lot of innocence. But his playing is not naive: it has an innocence and purity, without desperation. It’s like he’s having fun discovering even though he already has everything that he’s looking for.

Playing with Wayne gave me courage—courage to go deep and high. It made me play with more vulnerability instead of just bringing the hard licks that I’d practiced and prepared, which can be like a shield that you carve carefully before you come out of your room. Wayne taught me to present myself as open and vulnerable, inviting the other player to present his or her wisdom. It’s an invitation to learn together.

Wayne does that when we talk—he’ll ask a question not because he doesn’t know the answer but because he wants you to hear the answer yourself. Then all of a sudden things start to fix themselves. You don’t have to try so hard—sometimes you don’t have to try at all, and if you try harder you end up making it worse. That’s what I really learned from Wayne—and Herbie, too. Okay, you can be upset. But like Wayne told that member of his band one time, “What did you learn?”

There were some strange things, too, that happened on that tour. Every night it seemed Chepito was going through a new crisis. Thank God Wayne’s wife, Ana Maria, was there, because she would dismantle it. He seemed close to the edge all the time, saying stuff like, “Chepito is very upset today” and “Poor Chepito. He’s going to die next Tuesday.” It was always going to happen on a Tuesday. Armando would look him at him and say, “Why wait? Do it now, goddammy.” You could hear the tears suddenly stop. “Okay. What time is rehearsal tomorrow?”

Miles was part of the big jazz tour that we were on, and when he peeked in on our show in Rochester and was getting ready to leave before we had played, Chepito almost lost it. He went running up to Miles. “Wait—you haven’t heard Wayne and Carlos and me. Where you going?” Miles looked at him and just said, “Chepito, you’re still a bad motherfucker,” and walked away. “Did you hear what Miles called me? I am a bad motherfucker!” Then the tears started again, because he was happy.

Chepito always reminded me of Harpo Marx with a voice. Clown, troublemaker, and super talented—all in one. Earlier that year there had been a memorial concert for Jaco Pastorius, who had been killed in ’87. He had come to our concert in Miami the night he died, but afterward he hadn’t been able to get in some other club, and that led to a fight with a bouncer. Jaco went into a coma that he never came out of. Backstage at the tribute concert in Oakland was everyone who had a connection to Jaco or Weather Report or Miles: Wayne, Joe, Herbie, Hiram Bullock, Peter Erskine, Armando, Chepito. I had a bootleg tape of Coltrane we were listening to, and Marcus Miller came in. He said, “Hey! How’s everyone? What’s going on? What are you listening to?” We waited a second, and I said, “It’s good stuff—you should check it out.”

“Yeah, okay. Sounds good!”

I’m not sure if Marcus could make out who it was—the recording wasn’t the best quality—but Chepito picked up on this and couldn’t resist. He went, “So who are you?” Marcus looked at him and said, “I’m Marcus Miller—I play with Miles.”

“Yeah, I know Miles, but I never heard of you. What do you play?”

“I play bass.”

“Hmm. Okay, never heard of you.”

Marcus was hooked, and he tried explaining some of his other credentials, but Chepito just kept saying, “Never heard of you, man. Sorry.” Of course Chepito was just pulling his chain. By the third time he said that, Wayne and Ana Maria and Herbie were cracking up, and Marcus finally realized: “Oh! Okay—very funny.” That was definitely one of Chepito’s finest moments.

One night on that ’88 tour I said, “Hey, Wayne, you look so happy, man. What happened?”

“Miles just gave me back the rights to my song.”

I suspect that it was “Sanctuary,” because that was one of Wayne’s tunes on Bitches Brew, and it ended up with Miles’s name on it. I was happy for Wayne, but this happened almost twenty years after that song got recorded. Some things you have to watch out for in your life as a musician. Sometimes you have to stand up and say, “Look, man, this song is my song.” And you have to do it yourself. Even if you’re standing up to someone like Miles. That was the kind of advice I got from Bill Graham and Armando—you don’t have to be crass or vulgar or get upset, but speak up. The worst thing anyone can say is no.

The other thing that happened on that ’88 tour was that I got to see firsthand how certain jazz musicians were treated on the road compared to the way a Santana tour was run. I expected that things would be different in terms of the quality of hotels and the backstage thing—I’m not talking about that. Although I did get upset once when we were picked up in what looked like a laundry truck instead of a car.

I’m talking about a lot of stuff the concert producers were not paying me and Wayne for, like putting our likenesses on big posters and T-shirts and broadcasting the concert on the radio and recording it. None of that was ever okayed by us; we were getting paid only for the gig. Even then it was standard practice in the industry that if your show was to be recorded for radio or TV you were to receive another payment besides the fee for the concert. Same with merchandise.

So I found myself speaking up a lot on that tour, and I know to some people I must have looked like a prima donna—I remember some of the other jazzmen on that tour looking at me that way. But I just didn’t want to cooperate with an old-fashioned plantation mentality that seemed to be standard for jazz festivals and clubs. “Turn off those cameras, man, and don’t turn ’em back on until you guys ask permission and negotiate with us properly.”

Experiencing all that on the ’88 tour made me realize that it was imperative for me to be more hands-on with my own business. I have Wayne to thank in a way, because that tour forced me to be even more of a leader with Santana. I realized that some people around me weren’t even asking me questions, like whether I wanted to be on the radio and how much I thought I should be paid for it.

“Oh, it’s for later release on CD, but it’s to raise money for a charity.”

“Okay, what charity?”

The fact that these questions weren’t coming my way really started to bug me, and suddenly it all became a priority, and I became more involved with the band’s business decisions.

In a way I was waking up to the responsibility of caring how Santana was presented, so that the feeling and the message and even the spelling was all correct and accurate on album covers and posters and advertising and tickets. A lot of times other people just don’t have the same consciousness as you do or are too busy or just don’t have good taste. I remember thinking about how abysmal some of Miles’s and Coltrane’s album covers were. I started to demand to see everything—artwork, photos. “Okay, these three are the best—we’ll choose from these. These over here I don’t ever want to see again. Got it?”

The first example of this was Viva Santana!, which came out in ’88 and was a compilation that showed how far Santana had come in twenty years. It wasn’t just a “best of”—it told the Santana story through thirty songs and included a booklet with new original artwork that also used images from the covers of older albums. There were a lot of details and work that went into it, and everything came through me—this album I actually produced from top to bottom. We also did a documentary in which I talked about the band and myself and which included footage of Santana performing. It came out on VHS, then later on DVD, and now I think you can find most of it on YouTube. It really was the first attempt to show and explain Santana’s complete history, from “Black Magic Woman” to “Blues for Salvador,” in one package and in all the new technology and formats of the time.

At the same time we wanted to do a twentieth-anniversary reunion tour. It made sense—Viva Santana! was all about our history, so why not? Things were good between Gregg and Shrieve and me; Chepito and Armando were still in the band; and we had Alphonso to play bass, because Dougie was gone. David was not well at all, and we already had Armando and Chepito, so Carabello, who had his own band, didn’t come. We did a lot of tunes from the first three albums mixed with newer songs, and we ended the show with “Soul Sacrifice.”

I remember that whole project—the CD and the documentary and the tour—gave me more confidence in taking charge and having opinions about things beyond just the music. And I learned to have more and more confidence after the tour with Wayne—in many ways, I think the anniversary and tour helped to give birth to a whole new Carlos. The old Carlos was a nice guy who left a lot of things for other people to do and didn’t want to know about them. “I’ll just play the guitar, and you go take care of that.” The new Carlos didn’t want to be a control freak, but he decided there were things that he needed to be more hands-on about. It was that simple.

When your eyes are open, inspiration can come from anywhere. Here’s one example. I’m a huge fan of Anthony Quinn. Some people think he’s Greek, but he’s actually Mexican. He’s my favorite actor. I liked him in Zorba the Greek because of the advice he gives to the white guy: it’s a very important part of the movie. Zorba tells the man he needs some madness—because how else can he cut the rope and be free? Anthony Quinn was crazy—good crazy. I’ve seen his sculptures. And I know Miles, and the two of them had a profound mutual admiration for each other.

In ’75, when I was reading Sri Chinmoy’s books or other spiritual stuff, I was more interested in Anthony Quinn’s book The Original Sin, the first autobiography I ever read. He wrote about driving in Hollywood with a little kid in the passenger seat who did nothing but rag on him, telling him that he wasn’t worth anything, that he was nothing but a Mexican monkey playing plastic games, like all the people in Hollywood.

Of course that kid was part of himself—it was his guilt trying to put him in his place. We all have that same guy inside. There ain’t nobody who’s going to put you down more than you. But there’s a difference between being brutally honest and just being brutal. It really was a therapeutic book for me, because it connected with the same ideas and philosophy I was reading elsewhere. Anthony Quinn was asking the same questions—how to evolve and not make the same mistakes everybody around you is making. How to develop a bona fide spiritual discipline, with or without a guru.

He also wrote that he didn’t want to go to church because he didn’t want to apologize for being a human being. Whoa—Original Sin. I got it. Just what I had been thinking.

At the end of 1988, I was watching Quinn in Barabbas, in which his character is in prison and gets out because Jesus took his place on the cross, and in my head I kept hearing “You need to play San Quentin.” I was thinking, “What?”

“You need to play San Quentin—that’s the message of this movie.”

“This movie I’ve seen so many times?”

“Play San Quentin.”

I used to be able to see the prison from one of my first homes in Marin County. By ’88 I was living just a mile away. Having kids and a family makes you think about what you have and other people don’t and about the freedom you have to find your purpose and fulfill it. Those days there weren’t that many people wanting to play prisons—B. B. had played San Quentin a few years before, and I heard that only black prisoners went. I also knew about Johnny Cash playing Folsom State Prison—everybody did. My level of confidence was very high, having just done the tour with Wayne, and the guys in the Santana reunion band were gracious enough to be crazy enough to go do it with me.

I put that concert together myself—I arranged a meeting with the warden, Dan Vasquez, a Mexican dude. He said, “Let me get this straight. You want to do a concert in San Quentin? You need to come and walk the yard with me so you can see what you’re getting into.” I said, “Okay.” So even before I signed a contract to perform there I had to sign a waiver saying that if I got caught in any kind of trouble—if I were held hostage, for example—my family and I wouldn’t hold the prison responsible for whatever happened.

Then I stepped outside the offices, and we walked to the prison gates. I had guards with me, and as we stepped through and the gates slammed shut, the sound felt like a chunk of ice running down my spine. The first thing I saw were four guards, all with shotguns, walking a black prisoner somewhere. He was shuffling along in chains, and he had more hate in his eyes than I’ve ever seen in a human being. Then one of the guards with me said, “Look up at the ceiling,” and it was pretty high, but it was full of holes from shotgun blasts. “Those are from warning shots. Normally we have to shoot only one time up there—they know that the next time we’ll shoot them.”

We got to the yard, where everybody was doing things like lifting weights and playing basketball—whites, blacks, Latinos, Native Americans—and people started to recognize me. “Hey, ’Tana, is that you? What you doin’ in here, man? Hey, Carlos, what you doin’?” One guy got my attention. “Carlos, I just tried to cross the mountains from Mexico, and the next thing I knew they put me in here.” He was just a misplaced soul trying to get in the country, and he wound up in San Quentin. The warden said, “I see you’re connected with everybody here, man.”

We did two concerts outside in the yard—one for the hard-core criminals and one for the lifers. We did the set we were doing for the reunion tour but included some special songs that you’d think of doing in a prison: Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released,” Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal,” the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine.” We knew this was going to be a tough audience because we needed to reach blacks and whites and because maybe this wasn’t any one person’s music anymore. You can’t buy enthusiasm in San Quentin.

At first they were all just checking us out. By the second song they started to loosen up. I could see the energy changing in their postures and faces. By the third song it felt like they were thinking, “Hey—these guys can bring it.” By the fourth song they started to let the music in and smile and forget for a moment where they were. I mean, when I first walked in there I could smell the fear and the controlling of emotions, how bottled up everything was. How they could just explode. I could smell their skin, the clothes they were wearing, even their thinking.

There’s a photo from that show in San Quentin that’s on the wall in my office. I’m playing, and you can see some very hard-core prisoners on one side. You can zero in on them and see that they were hearing the music. I didn’t say much in those concerts—I let the music carry the message: this is required listening to help you not be a victim or a prisoner of your self, to help you change your mind about things and change your destiny. The message is the same inside prison walls or on the outside.

In a funny way, my life has always been local—everything that happens comes from where I am. John Lee Hooker was living in the Bay Area at this time. He was the Dalai Lama of boogie. Shoot, he should have been the pope of boogie as far as I’m concerned. We got to know each other. A lot of times we’d be playing, and he’d say, “Carlos, let’s take it to the street,” and I’d say, “No, John, let’s take it to the back alley,” and he’d say, “Why stop there? Let’s go to the swamp.” I miss him so much.

A John Lee boogie pulls people in as strongly as gravity holds them to this planet. He is the sound of deepness in the blues—his influence permeates everything. You can hear him in Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” or in Canned Heat’s boogies. That’s nothing but John Lee Hooker. When you hear the Doors, that’s a combination of John Lee and John Coltrane. That’s what they do; that’s the music they love.

The first time I heard John Lee, of course, was in Tijuana—on records and on the radio. As I said, there were three guys that had a lot of deep roots in their blues—Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jimmy Reed, and John Lee Hooker. Lightnin’ lived in Texas, and Jimmy Reed was probably the most viral when I was listening to the blues in Mexico, but he was long gone by the end of the ’80s. He made Vee-Jay Records a lot of money.

In ’89 John Lee was local to the Bay Area. He was living not far from me, in San Carlos, which is near Palo Alto. We met a few times and talked, and at some point he actually invited me to his house for his birthday, which was the first time I really hung out with him. I brought a beautiful guitar to give him.

When I walked in, I saw that everyone was watching the Dodgers on TV, because that’s John Lee’s favorite team. He was eating fried chicken and Junior Mints. No kidding—Junior Mints. He had two women on the left and two on the right, and they were putting the mints into his hands, which were softer than an old sofa. I stepped up and said, “Hi, John. Happy birthday, man. I brought you this guitar, and I wrote a song for you.”

“It sounds like the Doors doing blues, but I took it back from them and I’m returning it to you and I’m calling it ‘The Healer.’”

John Lee chuckled. He had a slight stutter that was very endearing. “L-L-Let me hear it.”

I started playing, and I made it up right on the spot—I knew how he did the blues, how he played and sang. “Blues a healer all over the world…” He took the song, and when he recorded it, he added to it in his own way. I said, “Okay, we’ve got to go to the studio with this, but I just want you to come at one or two tomorrow afternoon, because I don’t want you to be there all day, man. I just want you to come in and just lay it. I’m going to work with the engineer—get the microphones ready, get the band to the right tempo. You just show up.”

“Okay, C-C-Carlos.”

When John Lee showed up we were ready. I got the band warmed up—Chepito, Ndugu, CT, and Armando—no bass, because Alphonso didn’t make that gig. John Lee and Armando were checking each other out like two dogs slowly circling each other—they were the two senior guys there, and you could really tell that Armando needed to know who this new older guy was. He was looking at him slowly, all the way from his feet up to his hat. Just sizing him up. John Lee knew it, but he just sat there, tuning his guitar, chuckling to himself.

Armando threw down the first card. “Hey, man, you ever heard of the Rhumboogie?” He was talking about one of the old, old clubs on the black music circuit in Chicago, opened by the boxer Joe Louis back before I was even born. John Lee said, “Yeah, m-m-man. I heard of the Rhumboogie.” Armando had his hands on his waist like, “I got you now.” He said, “Well, I played there with Slim Gaillard.”

“Yeah? I opened up there for D-D-Duke Ellington.”

I saw what was going on and stepped in. “Armando, this is Mr. John Lee Hooker. Mr. Hooker, Mr. Armando Peraza.”

We did “The Healer” in one take, and the engineer said, “Want to try it again?”

John Lee shook his head. “What for?”

I thought about it and said, “Would you mind going back in the booth, and when I point at you, would you be so gracious as to give us your signature—those mmm, mmm’s?” John Lee chuckled again. “Yeah, I can do that.” I said okay. That was the only thing he overdubbed that day—“Mmm, mmm, mmm.”

“The Healer” helped bring John Lee back for his last ten years. He had a bestselling album and a music video—everything he deserved. We started to hang out more and play together. I would see him in concert, too. He had a keyboard player for many years—Deacon Jones—who used to get up onstage and say, “Hey! You people in the front—you might need to get back a little bit, because the grease up here is hot. John Lee’s about to come out!” I have so many stories like that as well as stories about John Lee calling me—sometimes during the day, but, like Miles did, mostly late at night.

I remember John Lee opening for Santana in Concord, California, and we had finished our sound check and he’d been waiting for me on the side of the stage. We were done, and he started talking to me while we walked away. The soundman came running up. “Mr. Hooker, we need you to do a sound check, too.”

“I don’t need no sound check.”

“But we have to find out how you sound.”

John Lee kept walking. “I already know what I sound like.” End of discussion.

One time there was an outdoor blues festival in San Francisco, and I went to support my heroes—Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, and others. The crew came running up to me, saying, “John Lee’s on stage, and he called out to you to come over and join him.” They’d already set up my amp, so I went over, and he was up there by himself, looking great, as he always did, in a suit and a hat. His guitar was on his knee. As soon as he saw me, he said, “Ladies and gentlemen, a good friend of mine—Carlos Santana. Come on, man.”

It was a beautiful day, and from the stage I could see the sky and birds and the Golden Gate Bridge, and all the blues lovers in the audience. I held on to that image and closed my eyes and joined him onstage—just he and I. It was like playing along with a preacher on Sunday morning—I waited for my time to step in, but while he was singing I could hear his voice telling me to start playing. I opened my eyes, and we were together in a groove, playing off each other. I heard his voice inside again, telling me to keep playing, so I closed my eyes and kept going. When I finished there was huge applause—people were freaking out. I looked around, but no John Lee!

I played a little more and thanked the people and went backstage, where John Lee was talking with a young girl. He looked up with that smile he had. “Hey, man, y-y-you did pretty good out there.”

“Yeah, but why did you leave me, man?”

“W-W-Well, I was done.”

I’ve always known where my heart is in music, but I really liked some new bands and guitarists that were coming up at the time. Vernon Reid reminded me a little of Sonny Sharrock and Jimi. His band, Living Colour, was from New York City and was one of the first all-black rock bands. Vernon’s a strong, funky player—fun to play with live. Vernon is a monster freak and has a beautiful heart. He and David Sancious both have quietness in their faces and a lot of wisdom, and, like me, both are into Sonny Sharrock.

Vernon played on Spirits Dancing in the Flesh, the Santana album released in 1990. I think about that album, and I hear the balance of Curtis Mayfield and John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix doing gospel songs, singing God’s praises, and rocking out. Prayer and passion. Alice Coltrane gave us permission to use John’s voice on one song. It was nicely recorded, but I still needed to feel raw emotion—I’d rather hear mistakes, you know what I mean?

There is nothing about singing to God and Jesus that should be whiny. The song should come from your heart and deep inside, not just from your mouth. An album about God has to be very honest and raw. A person who’s a little out of tune but totally for real is better than someone who’s trying too hard or being phony.

I wanted to work with a singer like Tramaine Hawkins, because with spiritual music I have to be very selective: sometimes people can get a little plastic when they praise Jesus. I won’t mention any names because I don’t want to hurt any feelings, but there’s a difference between whining and soul. When I hear Mavis Staples, Gladys Knight, Nina Simone, and Etta James, I hear a huge difference between them and singers from the other side of town, where the girls whine too much—black or white. They might be in tune, but it’s not real.

Tramaine came out of San Francisco and was with the Edwin Hawkins Singers for a while; she was perfect for Spirits. When I was doing that album I also got to meet Benny Rietveld, who was with Miles at the time. Alphonso was gone, so Benny ended up playing bass on the album and has been with me since ’91. He is now the band’s musical director. I’ve come to know and love Benny.

I had just started thinking about the album in ’90, and Wayne told me about the songwriter Paolo Rustichelli, who played synthesizers and was recording with Miles and Herbie and who had written a song for me. I ended up playing on Rustichelli’s album Mystic Man—with Miles on some tracks! Paolo gave me the song “Full Moon” to record, which I was working on when I found out that Benny was coming over. Meanwhile Benny heard we were auditioning bass players. We met, and he asked, “Hey, can I try out?” I looked hard at him. “You’re still with Miles, right? You can play with us, but you got to tell him.” I didn’t want any tension.

Of course you know what happened—Benny didn’t tell him, but Miles found out he recorded on my new album, and he heard we talked about Benny auditioning. I was at the Paramount in Oakland, where I had just given Miles a bunch of flowers and a gift for winning the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. After the show, I was getting ready to leave and was in the parking lot with my friend Tony Kilbert when John Bingham, who played percussion in Miles’s band, came to tell me Miles wanted to see me backstage. “Sure, I’ll be right there.” So I went back inside to his dressing room. “Hey, Miles.”

Uh-oh.

“Thank you for the flowers; thank you for the gift.”

“You’re welcome, Miles.”

“What’s going on with Benny?”

“I don’t know what’s going on with him. He’s in your band.” Benny had to do his own talking. Miles let me slide. The next thing I knew, Benny did tell him, and he joined the band and played on the album Spirits Dancing in the Flesh.

Spirits came out in 1990, but by that time Columbia and CBS had become Sony Music, and they didn’t know what to do with that album or the ones before it, many of which were not available anymore. I remember thinking just before Supernatural came out that I wish the record company would rerelease some of those albums, because they were so great—Freedom, Blues for Salvador, Spirits Dancing in the Flesh. I had that in mind a few years later, when I got a chance to put together Multi-Dimensional Warrior, the compilation of Santana music from the late ’70s and ’80s.

Spirits was the end of Santana’s relationship with Columbia, CBS, and Sony Music. They put a guy named Donnie Ienner in charge, and I couldn’t work with him. He wanted to work with me, but I was more in charge of the business side of Santana than I had been before, and I felt the same thing I think Miles felt when it was time for him to leave Columbia in 1986. Miles couldn’t work with the top guy at his part of the label, and if you feel that way, why stay? I remember my last conversation with Donnie—I listened to what he had to say and responded by saying something about how dealing with the situation was like “artists versus con artists,” and it didn’t get much better after that. I felt Santana needed to be somewhere else, and first we started to go with Warner Bros., then we ended up signing with Davitt Sigerson at Polydor.

The year 1991 was not easy—it felt like the spiritual training wheels were off. My pillars weren’t there anymore. My angels were leaving. It was very difficult. It made me grow up in another kind of way, as if God were telling me, “You’re on your own now.”

It all happened in one month. Santana was playing in Syracuse the day Miles died in California—September 28. Wayne called and told me that night. He said he had seen Miles playing that summer at the Hollywood Bowl. “He played ‘Happy Birthday’ for me, and in the middle of the song he looked at me and I saw a fatigue in his face that I had never seen before. Fatigue from many, many years back.”

I had seen Miles sick before, but I wasn’t expecting him to die. I got on the elevator with Benny and said, “Benny, Miles just passed.”

“No!”

We both looked at the floor, and I don’t remember much else. When someone like Miles or Armando leaves, there’s a vacuum, and you can feel the energy level go down. That’s the best way I can describe it.

The next morning I got up at five to take a plane so that I could attend Stella’s first-grade graduation. I was still numb. That night we played at Ben & Jerry’s One World, One Heart festival in Golden Gate Park. I sat in with the Caribbean Allstars, and we did “In a Silent Way” as a tribute.

I hadn’t seen Miles much in the previous year. I had sent him flowers in the hospital when I had heard he was sick, and he called to thank me. “This means so much, Carlos,” he had said. “What are you doing now?” I told him what I always said: “Learning and having fun, Miles.”

“You’re always going to be doing that—that’s the kind of mind you have.”

That was the last thing Miles ever said to me, and I wish more people could have known that side of him. His autobiography had come out the year before, and when I read it I thought he could have been more supported by the people who wrote it with him; they could have given him more honor. I thought they were overselling the Prince of Darkness bit. Not everything that came out of his mouth had to be written down. I’d rather read endearing things about him and other musicians. I like romance—I’m a romantic through and through.

Like an elephant, Miles remembered things. That time in ’81 when he came by the Savoy and we hung out all night, I had told him when we were backstage that the world would be grateful enough to him even if he never played another note. I said, “We just want you to be healthy and happy.” He said, “What’s that?” like it was a strange thing to wish on somebody. I immediately said, “Miles, you’re not one of those people who aren’t happy unless they’re miserable, are you?” He just stopped and looked at me. A whole year later I played a big rock-and-tennis event in Forest Hills, Queens—John McEnroe and Vitas Gerulaitis and Todd Rundgren and Joe Cocker and bassist Jamaaladeen Tacuma and the jazz drummer Max Roach were all there. We finished playing, and I was getting ready to leave when I heard someone call me. “Carlos! Hey, Carlos!”

It was Max Roach. “I need to talk to you, Carlos.” He looked serious. He said, “Miles came to see me. What did you say to him?”

Man, I had to run the videotape back a long way to remember our last conversation—it was that long night that started backstage at the Savoy. I thought about it, and two things came to my mind. First was the story Miles told in his book from way back in the early ’50s, when Max put some money in his coat pocket when he had been strung out on the street. Miles said that was what had shamed him into getting off heroin.

The second thing I thought about was the look he gave me when I asked him about only being happy when he was miserable. I had called Miles on his stuff that night, and I told Max the story. He listened to me and said, “I want you to know it’s working—he’s starting to look different.”

Who was Miles Davis? What made him do what he did? He maintained a vicious, ferocious pursuit of excellence no matter what he was doing or with whom—black, white, or any other color. As Tony Williams told me, “Before there were Black Panthers or black power or any kind of revolution, Miles wasn’t taking any shit from white or black people.” He had the fire and the fearlessness. But whether he was happy in the end is another thing.

If you look at advertising and movies and magazines, you’ll see that what they tell you is that success comes and then you’re happy. Here’s how to be happy: wear this, eat that, get this, get that. The truth is the other way around. I think what screams out loudest about anyone’s success is whether that person is actually, truly happy.

A few weeks after Miles’s memorial I was home and the phone rang in the morning and Deborah answered it. “No! No, no, no!” She started crying right away. “Bill is gone!” I said, “Gone where?” Then I got it, and that was it, man. For at least two months I was numb. Two of my closest friends—gone. Suddenly Miles was not there to call late at night and tell me when to duck. Bill is not there with a clipboard. Now I would have to do it all inwardly.

The last time I saw Bill was the month before at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. We had done so many shows together by then—it was an incredible evening. I remember being backstage after the concert, holding Jelli, who was just two years old. She was looking up at me with an expression of joy on her face, speechless. During the show, the energy had never dropped. Every song felt as if it had been just the right length and had segued perfectly into the next. The audience was a mix of white, black, Mexican, Filipino—a rainbow crowd. They were on their feet from the start of the show. Like Jelli, I didn’t know what to say. People were all around us—everyone was happy. Just perfect vibes.

Bill came over with his clipboard and looked at me. I waited. He slowly pulled off a page and turned it around to show me. It was blank. “Come on, man. Really? Wow, thank you, Bill.”

“Thank you.” Then he walked away.