CHAPTER 21

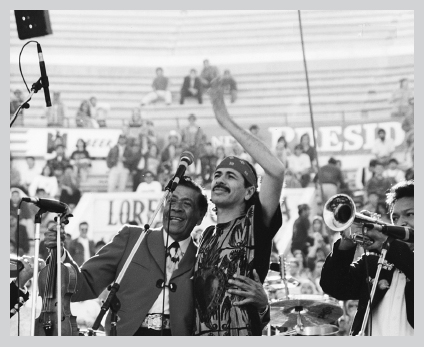

My dad, José Santana, and me at the Bullring by the Sea, Tijuana, March 21, 1992.

When I became a dad, I let my kids know I love them all the time. And naturally I would think about music and my obsessions and my kids. Of course I knew I wouldn’t be disappointed if Salvador, Stella, or Jelli chose music for a career—we’d have more to talk about. But they could have done anything they wanted and I’d still have been proud of their life choices. The only thing that would have made me disappointed would have been if they had let stuff get in the way of achieving what they want to do. Our family is a no-excuses family. Our children are responsible for their own quality of thoughts so that they can choose to turn them into actions and deeds and create their own lives.

It takes strength, man, to know when to let go of your kids—really, really let them go and trust them with the one who made them in the first place. One time in the mid-’90s, when Sal was a teenager, I needed to talk to him. I had been on the road for five weeks and had just come home. I understand that for kids between the ages of twelve and twenty-two, parents are the most uncool people ever. Right then Sal needed to play that out. I was thinking, “The kids’ll get over it, as I did, and then they’ll realize that their parents are exceptional.” But back then I was feeling a separation between father and son.

“Salvador?”

“Whattup?” That was his thing to say then—“Whattup?”

“Son, I’ve noticed lately that it’s your duty to contradict whatever I say. It seems to be a real 24-7 job, you know?” He kept looking at me. “But look outside: it’s an incredible day—the sky is blue, the weather’s warm. We can’t argue about that, right? Would you consider taking the day off with me and just sitting on top of Mount Tamalpais and looking at the hawks and the eagles and getting quiet?”

He surprised me a little, because he only thought about it a few seconds. “That sounds good.” We went up there and took our time, lay back, and looked up at the birds floating on the updrafts, and I didn’t say a word. In fifteen minutes he opened up, telling me stuff about himself and his girlfriend and school and the way people treat him because he’s a Santana and the fact that people are always asking him for money. It was a challenge to sit there and listen, just listen. I had answers and ideas to tell him. But I tried to look at him and see him as his friends and teachers do, and I saw that he was starting to figure things out on his own. He was always well behaved and respectful—he still is.

I’ll give you an example. We were on tour together in 2005—Santana and the Salvador Santana Band—and we were in San Antonio. Someone knocked on my dressing-room door. “Who is it?”

“It’s me, Dad. Salvador.”

“Son, you don’t have to knock. Come on in.”

“Dad, I need to ask you something.” I put my guitar down. “Can I get a bottle of water from your cooler? We ran out in our room.” I mean, he really does that. My heart just burst open.

“Sal, you can have anything, man, my heart included. Anything.”

“Uh, okay, Dad. Thanks—have a great show.”

I still embarrass him, I know. But I’m not changing, and neither is he. “How you feeling, Salvador?”

“Thanks for asking, Dad. I’m feeling good.”

You know, I want to be like him when I grow up.

In 1997 Prince called me to tell me he was playing in San Jose and asked me whether I wanted to come by the show and jam and just hang out. Did I? I love Prince. When I got there, he said, “Come here; I want to show you something.” Okay—what? Maybe a new guitar? He took me to a room backstage and opened the door, and his whole band was in there, watching a video. Prince was smiling. “They can tell you: every time before we go onstage, man, I play Sacred Fire. I tell them that this is what I want them to bring.” I looked at the band and thought, “Great—here’s another whole band that I’m telling what to do.”

It was an honor to be shown that by Prince—especially because Sacred Fire: Live in Mexico was as personal and special to me as Havana Moon was. It was a live video, and there was also a live album—Sacred Fire: Live in South America—that all came out together, the first time I did that sort of coordinated package—a tour, an album, and a video.

Sacred Fire came out in ’93, and the tour came from Milagro—my first album for Polydor the year before. There’s no doubt about it—there is a certain amount of spiritual confidence in Sacred Fire. My going to Mexico and playing there is a little like Bob Dylan going to play in Jerusalem. These are your people. You better bring it. In fact, I take a lot of pride in saying that Santana has never dropped the ball in Mexico City, New York, Tokyo, Sydney, Paris, Rome, London, Moscow—or any of the big cities. Yes, we have dropped the ball in other places because we’re human and we’re fallible, not because we planned to. Whenever it’s a major gig, I just take a deep breath and I say, “May all the angels really come forth and help me with this one.”

Milagro was a good-bye letter written especially for Bill and Miles. It opened with Bill’s voice introducing us as he always did—“From my heart, Santana!”—then followed with “Milagro,” which means “miracle,” because that’s what those guys were and what each of us is. That song used a line from Bob Marley’s “Work.” “Somewhere in Heaven” was the next tune, and it began with Martin Luther King Jr. speaking about the promised land. I didn’t know exactly where my angels were, but I knew Bill and Miles would still be calling and connecting, giving advice and spiritual blessings. I asked my old friend Larry Graham to sing on the album, and he came up with “Right On.” I put on “Saja” as the intro—that came from a very rare album called Aquarius and was written by the saxophonist Joe Roccisano. When I heard that song it sounded so much like something Santana would do if we had worked with Cal Tjader. I added that “Shadow of Your Smile” feel, then it slips into a soulful guajira.

I still like Marvin Gaye’s words, like “For those of us who tend the sick and heed the people’s cries / Let me say to you: Right on!” They have a strong message. I think it conveys the same message that’s in Santana’s music—it’s what I thought still needed to be heard in the ’90s. Still today.

I remember that after Larry’s first take, he asked me, “What do you think?”

I said, “Larry, you’re going around the block—you need to get inside the sheets.”

He laughed. “Okay! Got it.” The next take was it. Everyone knows about Larry’s bass playing, but he’s an incredible singer, too—at that same session, he did this amazing vocal warm-up. He went to the piano and played the entire keyboard, from the lowest to the highest key, and matched every note with his voice.

Another great Santana lineup came together on that album—I had CT, Raul, Benny, and Alex, plus we added Karl Perazzo, who had played congas and timbales with Sheila E. and Cal Tjader; Tony Lindsay, who had been singing around the Bay Area and had a nice, clear R & B voice; and Walfredo Reyes Jr., who’s from Cuba and played drums with David Lindley and Jackson Browne before he came to us. I also had a horn section that included Bill Ortiz on trumpet. Bill, Tony, Benny, and Karl are all still with Santana today. That pairing of Raul and Karl was especially nice and flexible—they respect the clave. They honor it: they know exactly where it is, as Armando did, but they’re not fixated with it.

The Milagro tour was going to Mexico, and my brother Jorge had already come along and played on a number of legs, so the idea of family was in the air. The plan was to shoot and record our Mexican dates: my father would come down to help open the show in Tijuana; César Rosas from Los Lobos and Larry Graham would play, too. I remember we took a flight to San Diego from wherever we were before, and the weather was really bad. It got so bad we thought the plane was going to go down. It started shaking a lot, then suddenly it dropped, and the coffee mugs the flight attendants were rolling down the aisle all hit the ceiling. One flight attendant ran to her seat, and I could see her crossing herself. The plane dropped again, and a little girl who was sitting near me started screaming—and laughing. “Whee! Do it again! Do it again!” Everybody started laughing, and that got us all relaxed. Then the shaking stopped.

In Tijuana, the local promoter called the concert a regresa a casa—a “homecoming.” They put the name on posters, and they got permission to use the city’s Bullring by the Sea. I think you could say that was really a turning point for me, when I became fully positive about and supportive of my Mexican self. It was a lot easier to go to Autlán, because so few people remembered me there. But in Tijuana a lot of people still knew me, and the whole town knew about my beginnings there on Avenida Revolución, though I didn’t have time to visit the old bars or clubs—and El Convoy was gone. We drove down the road, and in some ways it looked like it probably hadn’t changed that much. There were different names, different clubs, new places to dance, and not so much live music, but being in Tijuana was definitely like a homecoming.

We did two nights in the bullring, and the concert went on and on. It started with my father singing and playing with a band of local mariachis; then Pato Banton played, because reggae was really getting popular in Mexico then; then Larry Graham went on; and finally Santana played—with my brother Jorge and even Javier Bátiz gracing us by coming up and jamming. It was footage and music from other cities on that tour that became the DVD Sacred Fire. We also decided to shoot some black-and-white stuff in Tijuana, and we used that in the video for “Right On,” which was the lead single from Milagro—that’s the Tijuana bullring you see me playing in. Those shots of people crossing the border at night? That wasn’t staged—that was real.

There’s a tape that I found of that concert years afterward. I finally sat down with it and listened to it, starting at the beginning and going all the way through to the end. It was significant for me because that was the first time I heard my dad validate my music. At the end of his mariachi set, he spoke to me backstage. He was speaking a lot more than he usually did. “You know, Carlos, I heard your music many times on the radio, and I’ve seen you play, and there’s something very distinguishable about what you do. When I hear ‘Batuka’ or ‘Ain’t got nobody that I can depend on’—that’s Santana.”

I had never heard my dad say anything like that. I didn’t even know that he knew the names of any Santana songs, much less the lyrics. He knew the melodies. We had gotten so big so fast that I never got to see how my dad’s feelings about my music had changed. Anyway, he never did say much. He honored me by allowing me to become what he had been. It was like I became him, but on a vaster scale, and that was enough for him to stop telling me what to do and what not to do.

I got a chance to tell my dad what I had been holding inside me for many years. In ’93 the whole family got together for two weeks in Hawaii—it was all my brothers and sisters and their kids, plus my ex-wife’s parents and my parents. I said, “Hey, Dad, let’s take a break from all this—let the kids blow off some steam.”

We started walking, and I said, “You know, I’ve been wanting to tell you something.”

“I need to tell you how proud I am of you for taking care of all of us with that violin. I know you had to travel without knowing how much money you were going to get. We never missed a meal. I wanted to thank you.” He just looked at me. It felt good, like the look between any father and son that says, “We’re interconnected.” I could see validation not just for himself but for his father and my son, too.

I didn’t know he was only going to be around another five years. I still get choked up when I hear the tape from that bullring in Tijuana.

Playing in Tijuana was very difficult because of the local government and politics and the corruption that we had to deal with, but the guys at Bill Graham’s company—Bill Graham Presents, or BGP—get the thanks for making that happen.

But let’s just say I’m not a huge fan of what happened to BGP after Bill died. I think a few of the people who took over were the ones who would tell Bill what he wanted to hear, and they didn’t share his vision or his priorities or his commitment to music and the music community. I used to tell Bill flat-out that he’d never find out I was speaking about him behind his back because I didn’t mind saying whatever I had to say to his face. I wouldn’t kiss his ass, like some people who worked for him—but some of them talked horribly about him. I don’t think Bill had taken care of that side of his business before he died, because there had been no reason to—of course he hadn’t been planning on leaving that soon. Today some of Santana’s business is still in BGP’s hands—they own the memorabilia site Wolfgang’s Vault, for example, and you can find Santana posters and T-shirts there. We’ve learned to do business together, but I still feel like part of what Bill created was sold down the river.

Bill used to describe himself as “a sentimental slob.” I’m not that way. I learned that even if you have a sentimental attachment to some people, in this business it’s sometimes better not to have too many emotional ties. Then if you need to dismiss someone who isn’t helping things along or who can’t keep up while you’re moving forward, it’s okay. I know there are a lot of people who I have carried and kept with me when I should have let them go because they weren’t bringing in any vitality or adding anything to the energy or vision of the organization. It’s never easy—but in 1995, when I finally started my own management company, it was time to start looking at things that way.

We had started to handle all Santana management in ’88, and for a while Bill Graham had been like an overseer, with Ray Etzler as manager. We were still sharing office space with BGP. Then Bill died, Ray left, and Barry Siegel, who was our accountant, came in as business manager and worked with Deborah. She and I—and later my sister-in-law, Kitsaun—all became part of our own management company and learned a collective lesson about being more hands-on with the business, talking with lawyers and accountants, signing our own checks. Deborah was always in and out of the office, questioning whether things could be done better or cheaper. Her years running the restaurant with Kitsaun helped.

Kitsaun King was already a very important part of our family. She was working for United Airlines when we started Santana Management. During the ’90s she eventually became a full-time part of our musical family. She could be tough—over the years we butted heads about some band issues—but her instincts were usually right, and I never doubted her loyalty or her absolute determination to do what was best for Santana. I offer my condolences to anyone who was foolish enough to attempt to put me down or say anything bad about Santana in her presence. Auntie Kitsaun did not tolerate that.

In ’95 we found some office and warehouse space in San Rafael. Before that we were all over the place—renting storage space and rehearsal rooms when we needed them. So we came up with the idea of bringing everything all together under one roof. Deborah was the one who had the vision and intention to make that happen, and soon we had set up our own company. We got some of our favorite people from BGP—such as Rita Gentry and Marcia Sult Godinez, both very capable and easy to work with—because we wanted some familiar faces. I will be the first to say that working for me is no picnic. In fact I don’t need anybody to work for me—I do my own work, thank you. But if you say we’re working together toward a common goal, and that this is my role and this is your role, then yes, you should be working for me.

The funny thing is that even though we were taking better care of our business, I think that during those first years of having our own management company Santana was quieter in the studio than we had ever been in our history. We went almost seven years with no new Santana recordings, from ’93, when we recorded the concerts in Mexico and South America for the Sacred Fire project, to ’99, when I started to work on the songs for Supernatural. It wasn’t that there was a creative or musical problem. I never doubt myself with that kind of thing—I don’t get writer’s block. I know the music will come through me. It just felt like there was no need. I didn’t feel like recording. And we didn’t stop playing live—our touring schedule was busy.

I’d rather do nothing than make an album just to keep a music company happy. Also, Davitt Sigerson was gone from Polydor, so they moved us over to Island Records, where Chris Blackwell was in charge. Part of the new deal was that I got my own label, which I called Guts and Grace. There were four albums that came out on it—two by Paolo Rustichelli, one called Santana Brothers—that was Jorge and I and our nephew Carlos Hernandez, who plays guitar and is a solid songwriter—and one called Sacred Sources: Live Forever. That album compiled live recordings by Jimi Hendrix, Marvin Gaye, Bob Marley, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Coltrane, all message givers. It was a challenge to get all the parties to agree—all the estates and their lawyers—but it was worth it to release a lot of the rare music in my collection that maybe would never have gotten out otherwise.

Guts and Grace isn’t around anymore, but the good thing that came out of it is that I learned for myself that anybody can have a record label, but if you can’t get the music into stores or on the Internet and accessible to the public it’s like having a car without tires or gasoline. You need to have serious juice backing you up at the company you’re part of. Today, of course, it’s all different, with online sites and MP3s, but back then we didn’t know that the whole system of music stores and physical formats was going to change.

I felt bad because I didn’t have enough juice on my own to push Island to take care of my releases. It seemed like Chris Blackwell wasn’t all that hands-on by that time. In my eyes, Island had done some great things by bringing out Bob Marley and reggae music and all that African music on Mango Records, but by the end of the ’90s I think Chris would agree that nobody at Island was really present.

Managing your own career is not easy at the start—there’s a lot of stuff we didn’t know. We met with lawyers and accountants and other businesspeople to find out how we could get more money from old recordings and the group’s images and album covers and the name Santana. We started to study how other bands handled their business—Dave Matthews, the Grateful Dead, and Metallica helped us and showed us what they did. We started to ask the same questions other bands did—how can we use our money to help people directly instead of paying taxes that only end up supporting the Pentagon? We learned that everything in life is a process of learning.

In 1998 through Santana Management we set up the Milagro Foundation to help empower children and teenagers in crisis. That’s still the mission of the foundation. At the start, Deborah and Kitsaun helped manage it. Then we found Shelley Brown, who had been principal at Salvador’s elementary school in San Rafael. Her experience dealing with a public school, making it work for a rainbow of children, and basically holding them all together—black, white, Asian, and Latino—made us think she was the right person. She’s been amazing. Now it’s Shelley, Ruthie Moutafian, my sister Maria, and a full staff taking care of it. Since the foundation began, we’ve given away almost six million dollars to support youth in all parts of the world.

Why the name Milagro? Because I think life is about making miracles happen—that no matter how much money we give, the most valuable gift we can offer young people is to help them go outside the norms of belief, empowering them to believe that their dreams are not impossible and that they can allow the voice of divinity to take over their lives. If we can teach people to shoot three-pointers in basketball and how to have a healthful diet, we can also teach children in crisis to be happy for just fifteen minutes a day—then an hour, then the whole day—and that’s a miracle. If we can get people to stop criticizing each other—and themselves—and see the bright side of life, that’s a miracle. The foundation is about raising consciousness and awakening divinity at an early, vulnerable age.

It’s really the same message I tell audiences—you can make every day the best day of your life, starting with today. I think that’s the greatest miracle you can give yourself, and it’s not up to anybody but you. You can make it happen, starting right now.

Milagro started close to home, giving money to an organization that helps runaways who come through Larkin Street in San Francisco—where the bus station is. This organization gets to the kids before the drugs and pimps do, giving them a place to sleep and wash and get themselves together so they can figure out their next steps. We also support a community center in Marin City, where the staff teaches children how to grow plants—and we started sponsoring young musicians.

Another thing the foundation does is encourage programs that get kids away from inner cities even if just for a day—out into nature, to see trees and breathe fresh air. We’ve helped get young people out of Oakland and up to the redwoods, where the trees are like huge cathedrals that hide you from the rest of the world and look like they’ve been there so long you can’t measure them with time. Can you imagine how that looks to a child who’s never seen anything but streets and buildings and concrete? We’re not just raising consciousness—this is more like rearranging it.

Milagro is in Mexico now, too. In border towns such as Tijuana and Juarez, there are a lot of kids who are in crisis, surviving on the streets, and living in tunnels at night. They’re hungry, so they snort a lot of glue to take their mind off the hunger. We are trying to connect with them to save them from that kind of existence. In Autlán there’s now a health clinic and community center called Santuario de Luz—Sanctuary of Light—that Milagro helped found in 2005 with Dr. Martin Sandoval Gomez, and it’s really had an incredible impact on the town. The clinic provides ambulance service and modern facilities that Autlán has never had before. I visited in 2006, and they honored me. People came from various towns around Jalisco to meet me and tell me how their lives were affected by what we were doing with Dr. Martin. Hearing that felt better than receiving any number of Grammy Awards.

I think it’s important to understand that the Milagro Foundation started before we released Supernatural—it wasn’t something that came from asking ourselves, “What can we do with all this money?” It started from, “How can we share what we have?” It really goes back long before Milagro, to my mom and her powerful energy of sharing. She would tell us kids, “Everything tastes better when you share it.” And then she’d put ice cream or tacos or frijoles in front of us. Milagro is about providing food for the soul and the spirit, and just like real food, it tastes better when you share it with those who are in need.

Remember the charitable couple from Saint Louis—David and Thelma Steward—who said something that blew my mind: “It’s a blessing to be a blessing”? That’s right. It’s a blessing to be blessed with the resources and the Rolodex to help lots of people and make it work. It’s a community of giving that I became a part of, and I can’t be fooled by my own ego saying, “Look how special I am and what I’m doing.” I have to be open to meeting and supporting other people doing the same work.

Andre Agassi and Steffi Graf started a school in Las Vegas in the middle of the ghetto, and it has almost a 100 percent graduation rate. Some casino owners give money to the school, and there is a benefit concert every year that supports it—I’ve performed at the concert, as have Tony Bennett and Elton John. There should be schools like that in every city: if there were, I know you’d be able to see the benefits for the people living around them in just a few years. There’s a saying I’d like to see again and again—here it comes: Consciousness can be profitable.

I’m high knowing that there is a confederation of hope—Bill Gates, Paul Allen, Matt Damon, Sean Penn, Danny Glover, Bono, Elton John, Angelina Jolie, Morgan Freeman, Ashley Judd, George Clooney, Bruce Springsteen, the Dalai Lama, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and many others. They are all in line together doing what they really believe in. If only we had the opportunity to bring it all together and implement programs and schools and facilities that can help instill the mechanics of equality, fairness, and justice.

I’m also high that sometimes my phone rings and it’s Harry Belafonte. I don’t think anyone today has the same spiritual clarity and moral compass that he does—definitely no one has had it as long as he has. He was working against apartheid before Nelson Mandela went to prison, and then he fought to get Mandela released until it finally happened. He is a pillar of our community, a person upon whom people psychologically and morally depend to be present 100 percent and to not be any less than his light.

The first time we spoke I called him Mr. Belafonte, and he told me not to look up to him that way. “You’re one of us—we stand equal.” I told him I thought I was still getting there, but I could have melted right then when he said that. We talk a lot, and I think part of the reason we got close so fast is because we both carry a flame for freedom and stand up strong in our words and beliefs. The people who produced the Kennedy Center Honors event were thinking of asking Harry to introduce me at the ceremony in 2013, and I spoke with him about it. Harry said, “First I want you to look at a speech on YouTube.” It was the one he gave at the NAACP dinner honoring Jamie Foxx and others, and he spoke up about gun control and racism: “The river of blood that washes the streets of our nation flows mostly from the bodies of our black children.”

It was true what Harry said, and I was honored that he agreed to introduce me in the end. My friend Hal Miller gave me advice: he said that I was going to Washington to be honored by the nation and that this was not the time or place to go to war. “Enjoy and savor the experience,” he said. He suggested that I ask Harry to tone it down a bit, too. I told Harry, “Let’s take off the war paint.” Harry said, “All right—but not all of it.”

You can watch Harry’s introduction at the Kennedy Center Honors online—including what he said about me and controlling Mexican immigration. He decided to go for the laughs, but he still got his message across. I love his spirit and what he did that night. I’m very proud to call him a friend, and we’ve done a lot of work together, especially in supporting South Africa.

I think sharing and supporting are always about equality and justice. They are blessings—not something to be sold or kept away from people. If that’s being political, that’s okay. Mr. Belafonte—I mean, Harry—can’t be the only one speaking out.

I was once working with the actor Morgan Freeman against an anti-immigration law in Atlanta, and he said most people don’t understand that when politicians pass laws like that, they prevent people from contributing to the community and making it better for everybody. He was right—for society to grow, it must change. Growth means change, and it should be the same for everybody.

At the White House for the Kennedy Center Honors I was talking about this with Shirley MacLaine, and suddenly she stopped me. “What did you just say?” I said, “Patriotism is prehistoric.” She nodded her head. “Is that expression yours?”

I think what I was saying resonated with Shirley because she’s a forward-thinking person. I mean, we do need to upgrade the software in our brains and start looking at our planet from the aerial view. Even though you may not ever travel outside your hometown or even your neighborhood, you still are living here in a world that is all connected. It’s there for you to know and realize and hear—the Universal Tone, the sound vibration that reminds us that distance and separation are all an illusion.

To this day I detest anyone who tries to indoctrinate others into hating people because they are different and trying to get ahead and uplift themselves. I detest it as much as I did when some Mexicans were trying to get me to hate gringos. That’s what they tried to tell me in Tijuana, and I didn’t buy into that lie, either. We’re all people. The other stuff—like flags, borders, third world, first world—that’s all illusion. I like the idea of one global family under a single flag: a sun and a silhouette of a woman, a man, a little girl, and a little boy. All this other stuff keeps us stuck in the same place we were ten thousand years ago: Neanderthals fighting over some damn hill.

Any father can see himself in his little girl or boy. I think each of my children inherited a part of me, and then it got amplified. I also think each one of them—Salvador, Stella, and Jelli—have supreme conviction, like their grandmother Josefina. Sal is about respect and spiritual commitment. Jelli is political, the fighter for rights. She knows history and works in the Santana office with the archives. Stella always has something strong to say—she’s okay with the spotlight.

We used to call Stella CNN because she was always the first one jumping up to tell me everything when I came home. She’d be sucking her thumb, scratching her eyebrow, and talking: “And then you know what happened?” I would say, “No, but I’m sure you’re going tell me.” And then we’d hear about it in full detail. Stella was the one, if she thought she smelled any grass being smoked, who’d threaten, “I’m going to tell Mom!”

Stella’s my Josefina—the one who’s going to test you—more than Jelli and much more than Salvador. She’s also so like me in her feelings about school and church. Once I got a phone call from a teacher at the Catholic prep school that Stella was going to at the time. “I’m sorry, Mr. Santana, we seem to have a problem with Stella. As you know, we are a Catholic high school, and we teach Bible study. Today we were reading about Eve being made from Adam’s rib, and right out loud Stella started arguing about the passage—saying things like, ‘You guys don’t believe this stuff, do you?’”

That’s my girl. Then the administrators asked me to come in to the school about this one morning, and even though I usually am up late, I got myself there at 7:30 a.m. We didn’t really talk that much about Stella, but they showed me around the school for forty-five minutes, and then I knew what was coming. They showed me a space where they hoped to build a new gym, and would it be possible to do a few concerts to raise some money? Or maybe I could donate the money?

I was driving back home and was in the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge when I got a call from Stella. “Dad, what did you tell them?” She was asking about her argument over the Bible—she didn’t know about the fund-raising pitch. I told her I had the same answer to both things we discussed—no, I wasn’t going to reprimand her for questioning their beliefs, and when they asked for a donation I said, “Thank you for taking the time to show me the school. I have two questions—you do get tuition from all the students here, right? Also, I saw a huge photo of the pope when I came into the school. The Catholic Church is worth billions—can you ask him?” The principal said that for some reason or another they’d had an official divorce from the Vatican. I said, “Didn’t you get any alimony?”

The way I’d summarize Stella is that she was born to be the center of attention in the way she looks and holds herself, but at the same time she wants to be invisible. I’ll tease her and ask her how she can make that incognito thing work. She’ll just raise her hand and hold it to my face—“Talk to the hand.” I’m always learning new ways of communicating from my kids.

Jelli is the hippie of the family, the one who wants to help save the world. She called me the other day, and she was so excited—“I’m with Angela Davis!” She was at a lecture, and they had just met. Later Jelli told me that Angela had told her something that really stayed with her, something about having had more courage when she was young. I said, “Hmm. What do you think about that, Jelli?”

Jelli’s deep-rooted and no-nonsense. She’s a deep thinker, and she has a way with words. She loves Dolores Huerta. She also got arrested for trespassing last year at a protest in honor of Trayvon Martin. She got handcuffed, and we had to bail her out. I don’t know if she’ll do it again, because that was pretty intense, and you don’t want that on your record. But Jelli is Jelli.

When Jelli graduated from junior high school, all the students had to speak and quote somebody, and she got up and said: “I’m the one that’s got to die when it’s time for me to die so let me live my life the way I want to.” I remember thinking, “Dang!” She was quoting Jimi Hendrix. Jelli’s going to be a tough cookie. I remember looking in her eyes when she was born and thinking, “This one is really going to be intense—she has a different kind of thrust about her. She has the capacity to make a worldwide impact with whatever it is that she decides to be and do.” She hasn’t let me down yet.

My kids, when they come into a room, they bring the light with them. When I talk to them individually or collectively, they aspire, as we all do, to make this world a better place to live. I love them for that.

In the late ’90s, my dad began to play music less and less often. He still liked to walk and had never learned to drive a car. He also liked to listen to his music on cassettes. I think one of the best gifts I ever gave him was a Walkman—he would walk back and forth, listen to his music, and then transcribe the songs onto paper. I would visit my dad, and we’d sit on the sofa together. He’d reach out to hold my hand, and his hands were just like John Lee Hooker’s—incredibly soft. He used to touch my fingers and say nothing. That’s how we communicated at the end. José died on November 1, 1997.

When the end came I was by his bedside, watching and waiting, as everything started to shut down. The spirit stayed strong while the body got weaker and weaker. I went through that with my dad, then with my mom in 2009, and just this year—2014—with Armando. They all started to look like babies after they’re born: wrinkled and nearly hairless. They were filled with a light that got brighter and brighter. I wasn’t afraid, and I didn’t cry—it was time for each of them. I sat with them and held their hands and told them it was all right for them to move on if they wanted to. Everything would be okay here.

I’ve seen a lot of people crying. The only times I cried were at memorial services for Bill Graham and Tony Williams, maybe because their deaths were unexpected. I don’t remember crying for my mom or my dad—I think because I had a chance to say everything I wanted to say to them. When it’s my time to leave I pray that I have the strength to accept that all the things I had—my body, my skills, my brain, and my imagination—were borrowed from God. When he wants them back I’ll say, “Thanks, man, for letting me have fun with all this, because I really did.”

The last time I saw my dad clearly and closely was in a dream I had around a year and a half after he died. He was on a mountain, wearing his favorite blue jacket. I was in a car with my brother Jorge. “There’s Dad! Stop the car!” I ran up to him, and he was looking away, at a river that was bright and sparkly, like it was made of diamonds.

“Dad!” I really grabbed him because if I didn’t, I thought I might wake up and lose him. He turned around, and I could smell his scent. I felt his skin next to mine. Before I woke up, he looked at me and said, “He’s calling me. I need to go to him now. I need to tell you that I didn’t understand a lot of things that you did or said, but I want you to know that I do understand now why you are the way you are.”