CHAPTER 22

I’m not a big fan of awards shows, whether I’m watching them or in them—all the performers are going for the big bang, the big moment when they get to bring down the house. Too many times you can feel that desperation—“This is it, man. I got to take it to the top!” It’s the same kind of desperation felt by those guys who get to sing the national anthem, which is so difficult to sing because it’s such a strange song. I was watching an NBA game sometime in the ’90s, and I remember a guy who was dressed in a red suit and was a sports star who was not known for his singing at all who got up there and said, “Are you all ready?” like he was going to knock it over the fence. I was thinking that was a pretty cocky thing to say, but now you’d better bring it like Caruso, my friend.

I knew he was in trouble from the first note, because he started much too high—I was thinking he’d need an express elevator to get to the “rockets’ red glare,” you know? I believe if you’re going to go for the moment it should be the same moment you try to hit every night—success comes from lots of practice and supreme confidence in knowing who you are.

I’ve gotten better at playing awards nights and TV shows and knowing what to say when I’m asked to say a few words. I like it best when the band gets to play—I’m proud that Santana will bring it in one take, no matter when the red light goes on. We always know what we’re doing and what we’re going to sound like.

I also like some moments when it’s not Santana—it’s Carlos with somebody else, such as the time I got to play “Black Magic Woman” with Peter Green when they inducted Fleetwood Mac into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998. I was proud Santana got in the year before, but that was also when I gave them hell for not already having Ritchie Valens in there. I mean, what’s rock and roll without “La Bamba”? Rock and roll doesn’t mean white and popular—it means forever relevant. Ritchie was finally inducted in 2000.

I’ll tell you one of my all-time favorite moments. In 2004 I was being honored with a Latin Grammy Person of the Year award in Los Angeles. It was the usual scene—famous people in tuxedos and long dresses getting out of limos; lots of speeches and ovations. Quincy Jones and Salma Hayek presented me with the award, and before I even started talking someone yelled, “That’s my brother!” It was Jorge. The way he said that out loud and straight from the heart was so endearing I almost lost it.

Please don’t ask me to walk the red carpet. I did it for Deborah when her book came out—and I would do it anytime for Cindy. But most times when I show up to these kinds of awards shows, I go through the kitchen and greet the cooks and waiters and dishwashers. I still remember the feeling of my fingers in that warm greasy water and my hands getting all wrinkly.

And don’t ask me to sing the national anthem. I get invitations all the time to play it on the guitar; all I can do is try to play it as well as Jimi did. That guy who sang it at the NBA game? Clive introduced me to him one time at a Supernatural party—he was standing there with the saxophonist Kenny G. I didn’t laugh or smile, but I was going crazy telling my brain not to think about what I felt about smooth jazz and that performance at the basketball game. My inner voice said, “Just don’t go there, man.”

In 1997 I started to have a feeling that I was pregnant with something new—I had a new album inside me, and it was going to be something special. At that time I was going to call it Serpents and Doves, and it was going to consist of singles—the kind of songs that grab you immediately, something powerful with a message that can uplift and teach. It was time for some new music for the new millennium.

That year I was asked to speak in a documentary about Clive Davis and his philanthropy. I hadn’t seen or talked to Clive in more than twenty years at that point, but I knew that since CBS let him go in ’73 he had started his own record company called Arista and he’d had hits with people like Barry Manilow and Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin. I also had heard about his philanthropic work because of what we were doing with the Milagro Foundation—we were all in the same world.

I said I’d be happy to say a few words about Clive. “I’m going to tell the truth: the guy is really important to the music world and the well-being of people, too.” The producers sent a crew with a camera, and when Clive saw the interview I did he called me up. “Hey, Clive, how are you, man?”

“Carlos—thank you for what you said. What’s going on—what are you doing now?”

It was a good question. I hadn’t made a new Santana album in more than four years. “I’m trying to get out of my contract with Island Records. I owe them two more albums.”

“Well, as soon as you’re out of it, call me.”

By this time, Island was just part of the big salad at PolyGram, and it felt like Chris Blackwell was on his way out, so I was going to be stuck there in limbo with nobody. Chris heard I wasn’t happy, so he came to see Santana play in London, and he knew that the group was kicking booty as much as we ever did. Then he flew out to Sausalito to meet with me. We met at a restaurant called Horizons. He was going to try to convince me to stay. I remember he had to take a phone call, and when he came back he was complaining that he was having trouble with the new configuration at the record company. “They won’t spend the money to make sure I have good phone communication with my people.”

I was thinking, “Dang! What kind of message is that? Now he’s going to try and convince me to stay?” I didn’t want to take any more of his time or mine, so I jumped in.

“Chris, I respect you, so I want to be really up front with you. I have deep admiration for everything that you’ve done with Bob Marley and Steve Winwood and Baaba Maal and so many other musicians from Africa, Haiti, and around the world. To me you’re an ally and you’re an artist. But I know I have a really good album coming—I can feel it right here in my belly. It’s really important that I don’t give it to a label that’s going to let it sit in the back of some warehouse and end up being a tax deduction that nobody is going to hear.

“From one artist to another, let me go.”

Chris looked at me, and he looked at the ceiling for a while. He could see I wasn’t going to change my mind. Finally he said, “Carlos, tell your lawyer to call my lawyer. You’re free.” Just like that. He could have asked me to pay for the albums I still owed him or charged that amount against Supernatural when it came out—but he didn’t. He let me go with no strings attached, in a way that had a lot of integrity. For that I’ll be forever grateful to him—you could say that the first person responsible for creating Supernatural was Chris Blackwell.

The other initiator who brought me together with Clive and must get credit for making Supernatural happen is Deborah. Once I was free from Island, she was the one who said, “Okay, now you have to get back with Clive. It could be a good opportunity for you to hook up with him again and maybe get back on the radio.”

Radio? I remember wondering whether that was still around and whether it mattered anymore. It had been so long since Santana had any music on the radio. There was part of me that was thinking, “I just don’t have the wherewithal to understand radio now.” Not that I really did in the beginning, either.

I resisted calling Clive at first, because our last interaction had been way back in 1973, and Clive hadn’t been happy with the direction of Santana at the time. I knew that to work with Clive now would mean more than just discussing a song or two and then saying, “See you later—I’ll send you the album when we’re finished.” But Deborah told me to hear what Clive had to say. She was the key to us getting back together. She helped me get out of my own way when an angel was trying to help me.

I called Clive and invited him to come hear Santana at Radio City Music Hall. I stopped the show at one point and acknowledged him from the stage. “Ladies and gentlemen, we have in the house someone who, like Bill Graham, is an architect of this music. Without him it would have been really difficult for you to know who Janis Joplin, Sly Stone, and Simon and Garfunkel are—and a lot of other bands, too, including this one here. His name is Mr. Clive Davis.” It felt good to do that: it was the first time I had the chance to publicly acknowledge him that way. The audience gave him a standing ovation.

We talked after the concert. There really were only two questions: did we want to work together? And if so, how would we do it? Clive said something I liked—he was very direct, and he used a very spiritual word. “Do you have the willingness? Do you have the willingness to discipline yourself and get in the ring with me, to work together when I start calling everybody in my Rolodex? Will you trust me?”

He explained that he wasn’t into doing just another Santana album—he wanted hits. Anyone who has worked with him knows that Clive Davis only has one thing on his mind—it has to be number one on the radio every time. The message was that he would be involved from top to bottom—picking out songs, suggesting things in the studio, and deciding on the promotion strategy.

Clive told me something else. Even before we got together, he’d spoken to a bunch of musicians he was working with and asked them, “Would you be interested in working with Carlos Santana? Do you want to write with him?” I was surprised, because I was thinking he might have gone to some classic rock people—people from my generation. In ’95, we had done a tour with Jeff Beck that was great, and Santana—the original lineup—had been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in ’97. I was thinking old school, but Clive said, “Yeah, Lauryn Hill from the Fugees, Rob Thomas from Matchbox Twenty, Dave Matthews, Eagle-Eye Cherry—all those incredible artists and musicians, they want to work with you.” I knew the names and some of their music, and I liked this idea.

“They want to bring it to me, help get Santana back on the radio? Okay, then—let’s do this.” We signed with Arista.

Later, Clive told me that what persuaded him to do the project was that when he started making phone calls to see who’d be interested, everybody said yes. “I’m not lying—everybody. I knew I was going to do something with you, because no matter who I went to, the answer was yes.”

I was excited, because I had already started recording. Some of the songs on Supernatural I’d been wanting to record even before we talked. You can guess which ones. They sound like typical Santana, the kind my dad would have picked out: “(Da Le) Yaleo” and “Africa Bamba.” Clive got more involved with the sessions over time because of the collaborations and because of who he is and how he works—he can be hands-on, with supreme dedication to details such as song form and the match between musicians and producers. I had worked on collaborations before, but this was a Santana album that would have different groups and different producers on each track, depending on the style and direction of each song. That was a new thing for us.

I was blessed at the time with an amazing band—CT was with me, as were Benny and Rodney Holmes, who is a superb drummer with really incredible energy, a killer-diller. It was an honor to create Supernatural with him and some of the other people in Santana, as well as with the many other musicians who came in for each track.

I have to stop and focus on Rodney and some other drummers for a moment. Rodney is one of those musicians who is the whole package: he’s smart and can listen and react, and he has the right combination of chops and musicality. I first saw him play in a New York City club—I noticed that the pianist Cecil Taylor was there and went crazy just checking him out. Wayne Shorter called him Rodney Podney and put him in his band in 1996.

I’m particular about drummers. I make no apologies for that, because I’ve known for a long time that for Santana to be Santana we need a drummer with a nice fat groove and fearless drive—and the ability to listen and learn, to get into the music and make it spark. Just before Rodney we had Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez, who brought a strong Cuban feel, and a few years after Rodney, Dennis Chambers came into the band. Dennis is maybe the best power-groove drummer on the planet right now—such a serious pocket. He’s an institution unto himself—just mention his name and most drummers will get down on their knees to pay respect. Dennis was with Santana longer than any drummer—I think he intimidated some of the guys in the band at first because of his reputation, but as they got to know him they realized that he loves to joke and is very easy to hang with. Funny thing is that I met Dennis when he was playing with John McLaughlin in the ’90s. Right in front of John he said, “So when are you going to call me?”

That was one of the most important signatures of Santana through the years—a flexible drummer with a serious pocket and powerful drive, and two percussionists who can play anything and make it all happen together. We kept that sound for Supernatural.

Clive would call me. “I have a song for you. I’m coming over.” Or he’d say, “Wyclef Jean has something he wants you to hear.” Wyclef showed up and sang the song right there in the studio. He came in and walked up to me and put his face close to mine. It was like he was reading a musical score in my eyes—the next thing he was showing us the words to “Maria Maria” just as if he knew all about my family watching West Side Story and what that movie meant to Mexicans like us.

Clive could really get into the details. One time in the studio we were recording a tune, and he went right up to one of the singers. “Make me feel it. Make me feel it now, do you hear me?” His veins were popping out. I was like, “Oh, damn.” I didn’t know this side of Clive—I never saw it back in 1973! But he was right—that’s the same thing I ask for from singers: don’t be selling something, offer your heart. It impressed me that Clive could hear the difference. The singer looked at me like, “What’s going on?” I was thinking, “You should have brought it in the first place, man.”

The sessions were fun because they were all different. New people were coming into the band, such as “Gentleman” Jeff Cressman on the trombone, and I was getting to meet more musicians than I usually would. There were two I got to know really well and I’m still very close to—Rob Thomas and Dave Matthews. They’re both people who are very present with their music and their spirit, and they’re dedicated to both the spiritual and the outer realms. They want to make this world beautiful, and I think Clive knew that about them when he put us together.

The last two songs that we made for the album were “The Calling”—the blues workout with Eric Clapton—and “El Farol,” which has a melody that Sal helped write and is really a testament of the love that my son and my father had for each other.

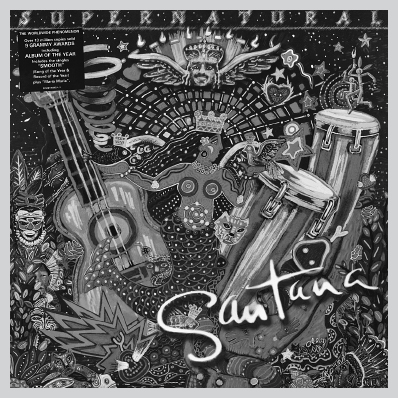

By the time we started recording, I had a name for this album: Mumbo Jumbo. I liked it because there really was a Mumbo Jumbo—an African king. We even had the artwork ready for the cover—a painting called Mumbo Jumbo by the artist Michael Rios, who designed many of the T-shirts I like to wear.

But when we were down to the last song, Clive told me, “You know, Carlos, I’m going to have to respectfully disagree with you. Most people think that ‘mumbo jumbo’ is a negative thing, like magic words that aren’t really magic, which is not what you want. Also, I think the press would have a field day with that name, and not in a complimentary way.” I said, “But Mumbo Jumbo was a real dude, you know—he was historic, and he healed people.” Clive said, “Yeah, okay, but… well, whatever it is, we need to go to press pretty soon.”

We came up with Supernatural, which has two meanings—“mystical” and “extra natural.” I was definitely okay with the invisible realm and with being very authentic. Plus it did bring to mind Peter Green and his instrumental “The Supernatural”—that’s a tune I still love. So okay, Clive—call it Supernatural, then.

Clive called a meeting when the album was done to get the troops ready, and he wanted me there. I was in his office with all the soldiers and warriors who were going to push the album—promotion people, marketing people, publicists. Clive played the whole album, and they gave me a standing ovation. I said that I was really grateful to Clive and to each of them because I knew that was the first time we were working together. Then I talked about the music. I said I tried to make sure that each note I played was as genuine and as fresh and as dangerous as a first French kiss in the backseat of a car—as fresh as the eternal now.

Suddenly Clive said, “Hey, Carlos—I’m very sorry for interrupting, but you just said something that I think says exactly what I feel about this album. Everyone knows you have a long history, but that’s not what is most special about this music. It’s so new and different, just like you were saying, and that’s what people need to know. We’ve got to work on it like it’s your first time making music.” I was thinking the same thing Bill Graham said: “Didn’t I just say that?”

Clive and I were really on the same page with Supernatural, all the way. He made sure that the world knew Supernatural was coming soon, in June of 1999, with magazine ads and billboards in Manhattan and Las Vegas. We were on tour that summer with Dave Matthews, and I remember Dave was always talking about how much support we were getting from Arista, and he was being very supportive too.

Dave really believed in the music—he came onstage one night in Philadelphia and introduced us, and we played “Love of My Life” together, and the audience loved it. We had written that one together—he came up with the words, and I got the opening part from a Brahms melody I had heard on the radio. After I went to Tower Records and sang it for the sales guy in the classical department, he recognized it right away. I got the CD, and Dave and I built the song around it.

I loved the way Dave shared his audience with me—talking to them about the music we had just made and opening his heart about how he felt. That was what I try to do with my own audience—putting stretch marks in their brains, opening some ears. That was the first time I really felt that this new music was going to be big—when the audience loved it. Just a few days after that Philadelphia show we were playing at the Meadowlands arena in New Jersey, and Dave looked up and saw an airplane pulling a gigantic banner that said THIS IS THE SUMMER OF SANTANA. He said, “Clive really likes you, man. You guys got it going.”

Clive had been saying that even before the album came out: “Carlos, this isn’t going to be just one or two million sold. This is going to really, really be something.” Then the music came out, and “Smooth” started slowly, but pretty soon it took off like a rocket. Supernatural starting selling hundreds of thousands of copies a week, and Clive would call me wherever I was and give me the updated sales numbers. I was in a taxi one time, and he was on the phone saying, “Carlos, they’re playing your music everywhere.”

I was having trouble hearing him. “I know, Clive—it’s on the cab’s radio right now.”

It went crazy, just crazy. Then “Maria Maria” came out, and it pushed sales to another level—even higher—and it just never came down.

The Santana lineup on the first Supernatural tours was on fire—we had CT, Benny, Rodney, and Karl, plus the horn section with Bill Ortiz and Jeff Cressman on trumpet and trombone. Because of them we were able to do some melodies from one of my favorite Miles albums—his sound track to the 1958 film Elevator to the Gallows. We also had René Martinez, who is a classical and flamenco guitarist who actually was our guitar tech, but he played with such dignity and elegance that we gave him a feature spot just before we did “Maria Maria,” and he’d bring the house down.

We crossed paths with Sting in Germany in 2000 at a few festivals, and he was scheduled to go on after us, but the first time he heard us, it was obvious he was impressed. Sting told me this in my dressing room one night when I was having a beer with my friend Hal Miller, who can be a real funny guy sometimes. “Carlos, who the hell is that drummer?”

“That’s Rodney Holmes from New York. He played with Wayne Shorter and the Brecker Brothers.”

“He’s amazing!” Sting said. “And who the hell is that guitarist?”

“Oh, that’s René Martinez, my guitar tech.”

Sting got quiet for a second. “Wait: he’s your tech? Unbelievable.”

Like clockwork, Hal stepped in and said, “Yeah. Wait till you hear the drum tech sit in—his name is Elvin.”

Sting just started laughing, and then we all did. That really was an incredible lineup, and I’m proud that many of them are still playing with Santana.

It’s really hard to describe how it feels when something hits that big, all around the world, and you’re in the middle of it. It’s like being that cork floating on a big ocean wave—how much am I controlling, and how much is controlling me? Every day the ego games have to be checked, and you have to find your balance again.

In February of 2000, Clive told me that Supernatural had been nominated for ten Grammy Awards. Deborah started calling me a new name even before we got to the show. “So, Mr. Grammy, how many do you think you’ll win?” The kids were like, “Yeah, Dad, how many?” I was feeling that I’d be lucky and happy with one. That’s why, when I won the first one during the event that takes place in the afternoon, I thanked everyone I could—Clive, Deborah, my father and mother and the kids. When I won the next one, I was thanking my siblings and the musicians and songwriters. By the time of the evening event, which was on TV, I felt like one of those dogs playing fetch with a Frisbee, and it became something to laugh about: winners in other categories, such as classical music and country, started thanking me for not doing an album in their genres.

The whole thing was a blur, really. The two things that I was most proud of were playing “Smooth” onstage, with Rob Thomas singing and Rodney Holmes bringing everything he had. I hit that first note, and everyone in the whole place jumped to their feet. My other favorite moment was when Lauryn Hill and my old friend Bob Dylan presented the Album of the Year award—that was the eighth and last Grammy that Supernatural won. They opened the envelope, and all Bob did was point to me—no words. I got up to accept it, and suddenly it was clear what I had to say.

“Music is the vehicle for the magic of healing, and the music of Supernatural was assigned and designed to bring unity and harmony.” I thanked the two personal pillars who first came to mind: John Coltrane and John Lee Hooker.

I have so many thank-yous to give, and a big one is to Deborah for helping me see the anger that was still inside me when I first went public in 2000 about being a victim of molestation. I hate that word—victim. I’m not someone who would walk into a room and say, “Hi, I’m the guy who was molested.” Survivor is better.

It used to piss me off, what had happened to me in Tijuana, and it pissed me off that I didn’t have a support system to protect me. At the same time, why didn’t I say something about the abuse myself? So it was anger and guilt and blame, spinning one to the other to the next, and it felt like a ball and chain. Even when I didn’t know what to call it, I knew I wanted a higher level of consciousness because I could tell that low consciousness is always dragging a ball and chain.

I think all people have something from the past, some pain or suffering that they must deal with, a negative energy that they need to transform and direct toward a place and time where it’s not hurtful to themselves or anyone around them. You have to heal yourself, and one thing I’ve learned in all my years on this planet is that if you want to heal something, you can’t do it in the dark. You have to bring it into the light.

That was when the angel Metatron said to me that it’s a must—I had to speak publicly about my past.

Metatron is the archangel whom I spoke about in all my interviews that year, the one who had promised to put my music on the radio and make it heard more widely than it had ever been heard before. “We kept our promise,” he told me. “We’ve given you what we said we would. Now we’re going to ask something from you.”

To explain it further, Metatron is an archangel, the celestial form of the Jewish patriarch Enoch, who appears in many books. I had been introduced to him in ’95, when I found The Book of Knowledge: The Keys of Enoch, which at first went whoosh!—right over my head. But the closer I studied it, the more I realized that in many ways it was a companion to The Urantia Book and continued what I now call a velocity to luminosity—understanding how the physical and spiritual planes, the visible and invisible, are interconnected in so many ways and how certain books can attain a divine synchronicity.

J. J. Hurtak is the author of The Book of Knowledge: The Keys of Enoch and a metaphysical historian and multidimensional archaeologist. I met him and his wife, Desiree, around the time of Supernatural, and they’ve become for me thought adjusters and enlightenment accelerators—like Jerry and Diane, Wayne, and Herbie. J. J. created a video of symbolic imagery, light, and color that corresponds to and almost dances with some prayer music by Alice Coltrane when I played them at the same time. That realization led me to introduce the two of them and suggest they work together. The result was an amazing album called The Sacred Language of Ascension, which combines Turiya’s melodies and organ playing with lyrics and chanting in English, Hebrew, Hindi, and Aramaic and which will, I hope, be released soon.

Back to Metatron—after The Book of Knowledge: The Keys of Enoch, I found The Revelations of the Metatron, in which Metatron takes center stage, and after studying that book I found that he would sometimes speak to me when I meditated. One night when I was in London doing promotional stuff for Supernatural—TV shows and interviews—Metatron spoke and said, “Now that you’re on the radio, you have to remind everyone they have the capacity to make their lives a masterpiece of joy.” But there was another thing.

“Then we want you to reveal that you were abused sexually, because there’re a lot of people walking around with that same kind of wound. Invite them to look in the mirror and say, ‘I am not what happened to me.’”

I resisted. I had to battle myself, because I knew my parents, my kids, and all my sisters and brothers were going to see whatever interviews I did. The Supernatural album was the biggest thing that year, so the spotlight was on me. It was time to get out of obscurity and go back into the mainstream—but I told myself, “No; I won’t do this.”

The angels didn’t back down—Metatron required selflessness. There was an interview in Rolling Stone and one with Charlie Rose coming up. I didn’t want to do it in either interview; I didn’t want to do it at all. I didn’t sleep for nights thinking about that. Then I did it in Rolling Stone: I told the world about what happened to me when I was in Tijuana. No dirty details—just the plain fact that I had been molested as a child and that I am still with purity and innocence.

It’s my inner voice—everyone has it. I had it at the Tic Tock, even in Tijuana. It stayed with me. If you don’t hear that voice you’re like a boat without a rudder. You learn to trust it. When I chanted or when it was quiet and late, I could hear it and would write down what it said. I told Rolling Stone about Metatron, too. “My reality is that God speaks to you every day… you got the candles, you got the incense, and you’ve been chanting, and all of a sudden you hear this voice: Now, write this down.”

Supernatural did so well and helped bring in so many new fans that all Santana albums were selling again, including the first album and even Caravanserai. Abraxas was a hit again—on CD. Young people were checking out our history, our whole catalog. Because of Bill Graham and the “all future formats” clause he had included, we were earning money on those albums at the same rate as when they first came out.

Santana used to travel sometimes in business-class seats and sometimes in economy and sometimes we stayed in motels. After Supernatural we were flying first class and staying at really amazing hotels. We started doing business as a partner with other businesses—helping to make their products, not just giving product endorsements. Our first partnership was with the Brown Shoe Company. We created a whole line of shoes under the name Carlos. Now we also make hats and tequila through these same kinds of relationships.

Our deal with Arista had to be redone, because they had gotten us cheap for Supernatural and they wanted to be sure they had our next album. The usual way that big record companies followed up a megaplatinum album was to give the musicians a big bonus, which really was an advance that had to be paid back in the end. But if the next album didn’t do as well, then the musicians would be stuck owing money until they had another hit. That’s what happened with Prince and Warner Bros.

Deborah came up with another idea, and we told our lawyer, “Let’s ask for a nonrecoupable bonus—so it’s really a bonus, not an advance that we have to earn back.” It would be a lot less, but we didn’t mind. “Let’s see what they offer,” we said. Arista made a nice offer, and that’s why Shaman came out on Arista. Real money is when you don’t have to pay it back.

The album changed our live shows, too. Our set lists were changing more and more back to songs. We pulled away from jams, and Chester and I didn’t write as much as before. CT stayed with us until 2009, but I think his desire to leave started with the Supernatural tours and the changes we were going through. After Supernatural, we pursued some albums that came out of the same idea, working with a lot of artists who brought their hearts so graciously to the collaborations—from Michelle Branch and Macy Gray to Los Lonely Boys and Big Boi and Mary J. Blige and all the others.

Everyone wanted Santana on all the TV and awards shows and we were trying to accommodate everyone and it was getting crazy. We even had trouble getting to The Tonight Show, so when we finally were able to get to Los Angeles with enough time we scheduled two tapings in one week. It was fun, and I remember Jay Leno was so gracious—he came up to me after we were done to tell me how grateful he was that we had been cooperative, and if there was anything he could do for me I should just let him know.

I knew exactly what I wanted. “Jay, you know I’m a huge fan of Rodney Dangerfield.” He’d been on The Tonight Show many times, since back in the Johnny Carson days, so I asked Jay if he could get me some of those recorded appearances to watch while we’re on the road.

The next day my office got an overnight package containing some DVDs—three hours’ worth of Rodney Dangerfield on The Tonight Show, from the ’60s up to his most recent appearance. He told some of his funniest jokes on that show. Man, I still watch those DVDs—I think my favorite parts are when Rodney would say something that pushed the limits of mainstream TV, and Jay would say something like, “There goes the show!” and Rodney would remind him, “It’s okay, it’s eleven thirty at night.” I love that kind of back-and-forth—Johnny or Jay reacting to him but really just egging him on.

In the summer of 2000 we did Supernatural live in Pasadena—all the songs with all the singers—and Arista shot it for home video. They asked me who else I wanted on the show, and I told them right away—Wayne Shorter. He hadn’t been on the album, and he was the one who didn’t fit into the picture, but I knew Arista had to say yes. Wayne and I decided to play “Love Song from Apache,” which Coleman Hawkins recorded and which I had played in ’94 in Montreux with Joe Henderson.

Wayne played a solo on the tune during rehearsal that caught everyone’s ears—everything went into slow motion, and the last note sounded like a falling star. You can hear it on one of the bonus tracks on the DVD. I felt so grateful to be able to do that concert, because everybody who played on Supernatural came and brought their best. But Wayne, he’s that bright angel on top of the Christmas tree. Here’s what he said that night about Supernatural: “This kind of album that reaches so many people is not even about the music. This is about social gathering and common knowledge of humans.”

I was thinking, “That’s exactly right. Woodstock was a gathering, and Supernatural is one, too. That’s the hope we should have every time we make an album or do a show: I’m playing tonight, and this won’t just be about the music—it’s a gathering.”

Supernatural happened because I didn’t step in my own way. I had the willingness to trust Clive, and he got on the phone with everyone and made it happen. For years, everywhere I went I heard Santana—radio stations, shopping malls, movies. The strange thing is that Arista fired Clive not long after Supernatural and put L. A. Reid in charge. The deal for Shaman was done with him.

Supernatural’s biggest impact was on my schedule. The longest time I spent on the road with Santana was from the summer of ’99 through 2000, and it required a lot of energy. I found myself doing five to ten times more interviews than I had done for any album in the past. We’d play, we’d travel, and I’d get up in the morning for yet another press conference. I know this is part of the job—it always was. I’m just saying that it was more intense than it ever had been before, and it required me to be present and convincing at a lot of radio stations and to talk about the making of the album again and again. People are curious—they want to know things about their favorite music, and you want to give it to them, but it can take a toll.

The good thing was that Santana is a band that has always been strong and ready for the road, so when Supernatural hit, we could handle all the dates that came to us. We weren’t coming out of retirement or anything like that. But the tours were longer than five weeks sometimes, so we had to suspend the Santana family rule for a while. At the end of 2000 I made a promise to cool things down for at least a year—we didn’t even start recording again for around six months.

Meanwhile, people—a lot of corporations—started dangling obscene amounts of money in front of us just to travel and play just one set. “We’ll pay all the hotels, all the air travel, and you get paid two and a half million dollars for forty-five minutes.”

No, no, no. I said, “There is no Santana right now—none.” I know the expression that you should strike while the iron is hot, but I unplugged the iron. I had to stop. There were problems with my being away so long, and I wanted to keep the family from falling apart. It made me realize that love should not be for sale.

I did an interview with a newspaper in Australia recently, and the interviewer asked me why I was one of the few survivors of the Woodstock family. I said that I had learned to listen to my inner voice, and my voice told me that it was going to help me so that I would not overdose on myself—so that I wouldn’t OD on me. Too many people who aren’t here today OD’d on themselves.

Then I told him, “When you come to my house, man, there’s no Santana there. It’s just Carlos.”

“What?”

“Yeah, there’re no Santana photos or posters or gold records in the house. I need to separate the person from the personality.” I still have to remind myself to do that. Sometimes it’s as Miles said in the liner notes for Sketches of Spain: “I’m going to call myself on the phone one day and tell myself to shut up.”

Around the time that Supernatural came out, this was our domestic rhythm: we were living in San Rafael in a nice house with a hill in front and beautiful hedges and flowers. There was an A-frame building nearby that I called the Electric Church, which was a term I got from Jimi Hendrix. That’s where I kept my musical life, where I got phone calls about work and hung out at night when I wanted to play music or listen to recordings or watch basketball or boxing. It was where I kept all my guitars, a Hammond and a Fender organ, drums, congas, and other percussion instruments. It had a special place for my records and audio and video collections. When friends such as Hal Miller and Rashiki would visit, they’d stay in the Church—it had guest bedrooms and a kitchen, too—and I’d come by around ten and we’d make plans for the day or they’d just run errands with me. In the ’90s I loved to drive out to Sal’s school to pick him up, even after it wasn’t cool anymore for me to do that.

About a hundred yards from where we lived was a house we built for Jo and SK, Deborah’s parents. My mom and siblings weren’t too far away in the Bay Area, so the kids really got to know their family. Our house was all about Deborah and the kids—no Santana stuff. When Jelli and I started hanging out a lot, we’d especially love to watch MADtv. I’d tape the episodes, then she’d come over to the Electric Church and laugh till she was rolling on the floor. But if the show got into anything that was too grown-up I’d tell her to cover her ears. Then she’d laugh even harder.

All the kids got into playing music for a while. They studied piano with Marcia Miget, and I used to take all three of them to their lessons. Marcia calls herself a river rat from Saint Louis—she knew all about her city’s musical history, including Clark Terry and Miles Davis and Chuck Berry. She taught Sal and Jelli piano, and Stella studied alto sax. I’m happy that I never missed any of their “graduation recitals.” I remember Sal doing a great job with “Blue Monk” and Stella playing a Pharoah Sanders ballad with beautiful tone and flow. Only Sal stayed with music, which is absolutely fine. I like the idea that all three of them have known what it feels like to hold an instrument in their hands and make music. Marcia was like a Santana family member for a while—she runs her own school now in San Rafael called Miraflores Academie.

We had a big German shepherd named Jacob—Jacobee, the kids called him. Sometimes he would get under the fence and go running around the neighborhood and Deborah would call me. “Hey, your dog got out again, and the Smiths want you to get him before he eats their cat, okay?” I’d put down the guitar and stop watching the TV. “Wait: who are the Smiths?” Then I’d go get Jacob.

I loved watching that dog when he was doing the things that made him jump and run around, his tongue hanging out as he was trying to catch up with his breathing. One time I took Jacob and the kids to Stinson Beach, around a half hour away from our house, and the dog found a dead seagull in the sand. It was like he just found a gourmet meal—he jumped on it and bit at it and started rolling in it, man. He needed to get that nasty stink on him.

I was thinking, “Damn. How much do you have to love something to throw your whole body into it like that?” You want it so bad you want to wear its smell. I started to think about how that happens in music—how some musicians go for it, get into a song, and squeeze their bodies in between the notes.

One time Jaco Pastorius and I were playing with some jazz cats at a special session, and the other musicians asked him what he wanted to play. He smiled at me, then said, “Fannie Mae,” which is an old jukebox song by Buster Brown—not the kid who lived in a shoe but a blues singer of the 1950s and ’60s. The tune is a simple blues with a shuffle. The other musicians either didn’t know it or didn’t want to play it, but Jaco started it off and got into it just as Jacob got into the seagull on the beach. He was just so into the feel and heart of that song. I kept thinking, “That’s the kind of spirit and conviction I want to have in Santana.”

I got the kids to jump into the ocean so Jacob could run after them and wash off that seagull funk. It’s really something to watch someone be himself.