October 1908, and Muriel Matters, back from vanning, was concealing something beneath her garments that no one expected. The conception had been sharp and painful. Some saw it coming; others smirked. It was inevitable, they said. It’s a wonder it didn’t happen sooner. As Muriel stood outside the House of Commons, waiting to enter, she had only a moment to pause and reflect on the origins of her secret.

Sunday 11 October. The summer had been a protracted and fiery one, by English standards at least, with temperatures reaching into the eighties Fahrenheit (high twenties Celsius), and the heat continued well into autumn.1 Truly our British climate plays strange freaks, wrote the COVENTRY EVENING TELEGRAPH on 30 September of the abnormal heat wave.2 Emmeline Pankhurst remarked that the summer was one of the most oppressively hot seasons the country had known.3

And the citizens were getting not just sweaty but toey. At the end of June, a hundred thousand people had gathered outside parliament to no avail. That evening, a suffragette threw a rock through the window of the prime minister’s residence at 10 Downing Street. (The smashing of windows, remarked Emmeline Pankhurst, is a time-honoured method of showing displeasure in a political situation.4)

No one was more impatient than Emmeline. She was waiting for a reply to a respectful letter she’d written to Asquith asking whether his government was planning to debate a Women’s Enfranchisement Bill in the autumn session of parliament. The bill had been before the Commons for nearly a year, since late 1907.

On 9 October, Emmeline received her reply. To no one’s surprise, Asquith nixed the bill.

A plan of action was ready to go. Women, Emmeline warned the government, would enter the House to plead their cause in person.5 If they could not vote, the women would have no other recourse than to assert the essential justice of making women self-governing citizens.6 Speaking in the Commons was, technically, the last constitutional means open to them.

Emmeline now called a mass public demonstration for Sunday 11 October. She, Christabel and a pregnant General, Flora Drummond, rallied the troops from the plinth of Nelson’s monument in Trafalgar Square, a traditional place to vent communal unrest. The three suffragettes exhorted Men and Women to join them to Rush the House of Commons on 13 October. If they could barge their way in en masse, someone could exercise the oldest of political rights… the constitutional right of the subject to petition the Prime Minister as the seat of power.7

They didn’t make it as far as the front gate of Westminster, let alone the seat of power. Police had been taking notes at the Trafalgar Square rally, and the following day all three—Emmeline, Christabel and Flora—were arrested on a charge of ‘inciting to riot’.

Christabel represented the trio at the ensuing show trial. The magistrate denied her request for a jury. Christabel decided they might as well make it a real celebrity circus and subpoenaed Gladstone and Lloyd George, who had both been present at the Trafalgar Square demonstration. In her cross-examination, Christabel pointed out that it had been the home secretary himself who had advised the women to take matters into their own hands.

The press devoured her brilliant show of legal nous, with one paper calling her London’s Lady Lawyer. Miss Christabel Pankhurst would have been a barrister had the man-made rules of Lincoln’s Inn allowed her to eat her dinners there, said the WILLESDEN CHRONICLE, and the indications she gave the other day show that it is a profession in which she is likely to have achieved fame.8 All three women were found guilty nonetheless.

It was a result the Pankhursts had anticipated. I may not see you again for six months, Emmeline wrote to Elizabeth Robins, head of the Actresses’ Franchise League, for I have a feeling that the magistrate means to give us as long an imprisonment as the law allows him.9 She was right, and wrong. All three women were to be incarcerated in Holloway, Emmeline and the General for twelve weeks, Christabel for ten. Before being taken away, Emmeline addressed the magistrate:

I want you, if you can, as a man, to realise what it means to women like us. We are driven to do this, we are determined to go on with this agitation, because we feel in honour bound. Just as it was the duty of your fore-fathers, it is our duty to make this world a better place for women than it is to-day…We are here not because we are law-breakers; we are here in our efforts to become law-makers.

With that, the magistrate sent the women—mother, daughter and expectant mother—to gaol, not with the status of political prisoners, but as common criminals, to be treated as pickpockets and drunkards, as Emmeline lamented. There they joined scores of other suffragettes who had chosen prison rather than paying their fines for window-smashing, using insulting language, failure to move on, obstructing the pavement and other petty crimes of protest.

Asquith had locked up many of those who had thrown their bonnets in the ring for the cause; now he had the ringleaders. Nailing the Pankhursts was the cherry on top.

So on 28 October, there was Muriel Matters: standing outside the House of Commons while the Trafalgar Three awaited their sentence. She had no intention of rushing anything. She would execute her purpose steadily, with systematic calm, knowing that her secret weapon was safely concealed beneath her clothing. Fortunately, the autumn days had finally cooled, so it was not conspicuous that the woman showing her ticket to climb the stairs to the Ladies Gallery was bundled up in a heavy coat.

When Teresa Billington-Greig conceived of the plan to show the government that suffrage militancy could be fought on many flanks simultaneously, Muriel had eagerly volunteered to execute it. Another young WFL member, Helen Fox, agreed to accompany her. On the morning of 28 October, according to Sylvia Pankhurst, all the world had awakened to find little placards posted on every hoarding. (It is quite possible that this is one occasion when Dora and George Coates tiptoed around at midnight, paste pot in hand.) The posters read: Proclamation. Women’s Freedom League Demands Votes for Women This Session.10 The stage was set.

At 5.30 p.m., the actors took their positions. Muriel and Helen were escorted to the eyrie of the Ladies Gallery by Stephen Collins, the well-meaning MP who had unwittingly agreed to provide two gallery tickets to a pair of curious ‘public servants’. Muriel, costumed in her heavy coat, carrying a book of Robert Browning poetry and a box of chocolates, mellifluously thanked Mr Collins and entered the small, airless chamber. She saw that the other WFL members had already arrived—there was her dear friend Violet Tillard, a Votes for Women poster obscured beneath her cloak. The gallery was surprisingly full of MPs’ wives, considering that it was a banal licensing bill that was being debated.

Muriel took a seat in the second row and waited. For three hours she waited. The minutes dragged, then flew, alternately, according to the beats of my heart, Muriel later recalled.11 Finally, it was the droning of a Tory MP, the Dickensian Mr Remnant, that gave Muriel her cue. At 8.30 p.m., a woman in the front row abandoned her seat and Muriel darted to take her spot.

She was now sitting within spitting distance of the despised metal screen that separated the Ladies Gallery from the floor of the House below, that vile grille behind which women have had to sit in the House of Commons for so many years.12 Though Muriel had only been in England for three years she well understood, as she later explained to Australian readers, that to suffragists the grille was one of the symbols of man’s conventional attitude towards women.

The House of Commons represents men’s opinions solely. The actual building plainly demonstrates this. All kinds of men are admitted freely to various parts of the House, but to women is allotted only a small, remote gallery in an obscure corner with a heavy iron grille in front, quite an Oriental custom.13

Reduced to a faceless blur in a distant harem behind the nine panels of iron lacework, women could neither see nor be seen. There was only one thing for it. These stupid conventions, founded on and nourishing inequalities, must be broken down.

There were two exquisite ironies in what happened next. The first was that the woman who volunteered to symbolise the rebellion—to emancipate myself—was already a politically enfranchised woman. The second was that she used the symbol of servitude—the chain—to execute the revolt.

Muriel Matters, an Australian suffragette, as the papers made sure to note the next morning, now stood, reached beneath her coat and unfurled the heavy link of chain she’d wrapped in muslin to stop it clinking and giving the game away. She had a leather belt around her waist and, around that, one end of the chain was securely fastened with a keyed padlock. The other end she quickly bolted to the grille with a self-locking Yale padlock. Snap! Muriel had travelled thousands of miles to reach London and now she wasn’t going anywhere. It was over, she realised exultantly, over in a second.

But that was only the start of the performance. Muriel had a speaking part and now, over the tedious oration of the unsuspecting MP on the floor of the House, she began to recite her lines, her flat Adelaide accent modulated by years of elocution training.

Mr Speaker, members of the Il-Liberal government. We have sat behind this insulting Grille for too long. It is time that you ceased to legislate merely on effects, it behoves you to deal with primary causes. You are discussing a domestic question, and it is time that the women of England were given a voice in legislation which affects them as much as it affects men. We demand the Vote.14

Now for the chorus. In the commotion, Helen Fox had similarly fastened herself to the grille. The women of the country demand the vote, she roared, her lips poking through the grille like a child trying to taste ice on a lamp post. Violet Tillard jumped to her feet and pulled out the poster she had hidden beneath her cloak, the same as the ones all London had woken to that morning. Violet pushed the poster through the lacework of the grille, whence it unrolled to reveal the ‘proclamation’.

Now a diversion. Someone stood up in the Strangers’ Gallery. I am a man, Thomas Simmons cried out, and I protest against the injustice to women. The Strangers’ Gallery was elevated, but not obstructed by an iron screen. Simmons tossed a sheaf of pamphlets over the simple railing, showering the House with suffrage propaganda.

There was now no doubt as to what was occurring. It was an ambush. While the leaders of the WSPU were anxiously awaiting their fate in court, the press hanging off every detail of the trial, the WFL had swooped in to launch a surprise attack. It was, wrote the league’s Stella Newsome, a red letter day in the history of the women’s suffrage agitation15—the particular genius of the action being that it was now incumbent on the politicians present to decide what to do next: a choose your own political adventure. Adjourn the session, or ignore the ruckus in the gallery and continue with business as usual? Valiantly, Mr Remnant prattled on while the parliamentary SWAT team went to eject the insurgents.

But when the attendants burst into the gallery to apprehend Muriel and Helen, they soon discovered the women were immovable. Where was the key? they demanded. (The key was in fact tucked down the back of Muriel’s dress.) You cannot get me away, Muriel laughed defiantly, and she was right. One man tried to rip Muriel from the grille, jerking her head back violently and knocking her into a chair. Another grabbed at her mouth, attempting to muzzle her with his hand. A WFL accomplice sitting in the gallery jumped on the man’s back, and it was on for young and old. Cowards, bullies, shouted the remaining women in the gallery.16

Since they couldn’t remove the women—who were still crying continually in shrill voices their demand for immediate votes for women, according to the NOTTINGHAM EVENING POST the next day17—from the grille, they would have to remove the grille from the gallery. In sheer desperation, the HAMPSHIRE TELEGRAPH reported, the guardians of law and order had to wrench the panels of the grille from their sockets and bodily convey ladies, grille, chains, and all out of the gallery. THE TIMES described the scene as a farcical procession, as the women were dragged, carried and pushed out of the gallery and down the staircase, still attached to the panels of iron trellis. Muriel was taken first. One of the policemen had his hand around her throat. The gallery had been cleared of women, who now formed an impromptu honour guard for Muriel and Helen’s journey along a corridor to the committee rooms. They cheered the women and jeered the police. Mr Remnant, determined to be the last man standing, continued to expostulate on the position of the Licensing Commission and its attitude in relation to the assessment of compensation. He could barely be heard over the din coming from above. Many MPs left the House to get a front row seat in the committee room.

Inside the room, a legion of police waited for the two malcontents and their iron appendages. A blacksmith filed through the chains. Muriel fully expected to be arrested, but to her surprise, she and Helen were escorted from the premises and released via a back entrance.

By now, crowds had gathered around the front at the St Stephen’s entrance. In part, the crowd was composed of spectators who had come to see what the morning papers would call Extraordinary Scenes in the House of Commons.18 The sea of intrigued onlookers was swelled by a scrum of reporters vying for a scoop. But there was also a vocal group of WFL members who had staged a co-ordinated demonstration inside St Stephen’s Hall, leading police in another game of tig when the long arm of the law tried to move them on. Finally ejected from the building, some women mounted the statue of Richard I, near where Nellie Martel had begun the first open air protest on that fateful day of 12 May 1905. Almost three and a half years later, with no victory in sight, the women could do little but hang on for dear life as police tried to rip them bodily from the statue.

It was here, as one protester clung tenaciously to the legs of Richard’s horse, that a battered and bruised Muriel finally achieved her aim. From the centre of the crowd, she demanded admission to The House of the People, shouting: It is as much a House of women as it is of men. With these revolutionary words, she was arrested for ‘wilfully resisting police’, and taken to Cannon Row police station.

Sylvia Pankhurst later assessed that, although the grille was soon restored, even the temporary dismemberment of a fixture which seemed so strikingly typical of the long enslavement of women was widely regarded as a triumph.19

And this was the beauty of Teresa Billington-Greig’s plan. The poetry of protest. What attracted so many women in such great numbers to the movement, she realised, was not suffrage per se, but insurgence, insurrection: to cast away these chains.

It was women crying to the masculine sovereignty: ‘You do not only deny me the right of self-government, you deny me the right of rebellion against bondage, against the worst servitudes, against every manifestation of your control. This first right I take. I disavow your authority. I put aside your cobweb conventions of law and government. I rebel. I claim my inalienable right to cast off servitude. I emancipate myself. And the liberty I have claimed and taken you shall register in the writings of your law.20

I rebel. Je suis prêt. I am ready. And so is she. And so is she. By such logic is an army raised. Particularly when there is a valiant leader, also equipped for action.

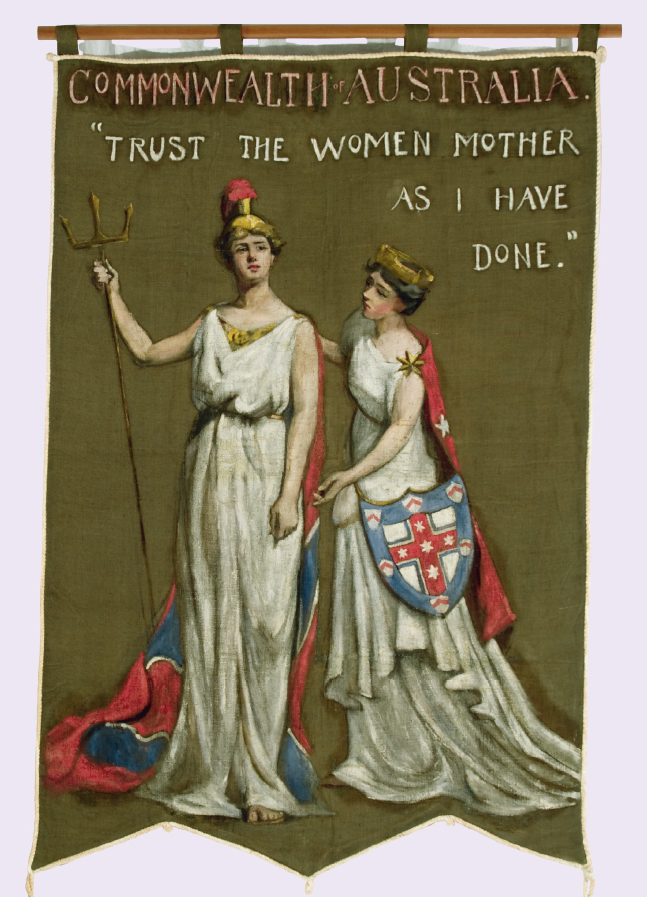

Dora Meeson Coates’ very large banner for the Commonwealth, painted in her Chelsea studio in the summer of 1908.

A meeting of the WSPU inner sanctum at Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s apartment, 1906. From left: Christabel Pankhurst, Annie Kenney, Nellie Martel, Emmeline Pankhurst, Charlotte Despard. The photo was taken by Sylvia Pankhurst.

Up, up and almost away. Muriel Matters in her rented airship, February 1909.

Nellie Martel braves the threat of eggs and peas to front a jocular all-male crowd. Place and date unknown.

Dora Montefiore ‘harangues’ the crowd from her window at ‘Fort Montefiore’ during the Siege of Hammersmith, June 1906.

The London Illustrated News’s depiction of Muriel Matters—the Heroine of the Grille—a media sensation in the autumn of 1908.