For millennia women have sat together spinning, weaving, and sewing. Why should textiles have become their craft par excellence, rather than the work of men? Was it always thus, and if so, why?

Twenty years ago Judith Brown wrote a little five-page “Note on the Division of Labor by Sex” that holds a simple key to these questions. She was interested in how much women contributed to obtaining the food for a preindustrial community. But in answering that question, she came upon a model of much wider applicability. She found that the issue of whether or not the community relies upon women as the chief providers of a given type of labor depends upon “the compatibility of this pursuit with the demands of child care.” If only because of the exigencies of breast feeding (which until recently was typically continued for two or three years per child), “nowhere in the world is the rearing of children primarily the responsibility of men. . . .” Thus, if the productive labor of women is not to be lost to the society during the childbearing years, the jobs regularly assigned to women must be carefully chosen to be “compatible with simultaneous child watching.” From empirical observation Brown gleans that “such activities have the following characteristics: they do not require rapt concentration and are relatively dull and repetitive; they are easily interruptible [I see a rueful smile on every care giver’s face!] and easily resumed once interrupted; they do not place the child in potential danger; and they do not require the participant to range very far from home.”1

Just such are the crafts of spinning, weaving, and sewing: repetitive, easy to pick up at any point, reasonably child-safe, and easily done at home. (Contrast the idea of swinging a pick in a dark, cramped, and dusty mine shaft with a baby on one’s back or being interrupted by a child’s crisis while trying to pour molten metal into a set of molds.) The only other occupation that fits the criteria even half so well is that of preparing the daily food. Food and clothing: These are what societies worldwide have come to see as the core of women’s work (although other tasks may be added to the load, depending upon the circumstances of the particular society).

Readers of this book live in a different world. The Industrial Revolution has moved basic textile work out of the home and into large (inherently dangerous) factories; we buy our clothing readymade. It is a rare person in our cities who has ever spun thread or woven cloth, although a quick look into a fabric store will show that many women still sew. As a result, most of us are unaware of how time-consuming the task of making the cloth for a family used to be.

In Denmark fifty years ago young women bought their yarns ready-made but still expected to weave the basic cloth for their households. If they went to a weaving school rather than being taught at home, they began with a dozen plain cotton dish towels. My mother, being a foreigner not in need of a trousseau, and with less than a year at her disposal to study Danish weaving, consented to weave half of one towel to get started. The next assignment was to weave three waffle-weave bath mats. (Indeed, the three were nicely gauged to last a lifetime. The second wore out when I was in college, and we still have the third.) Next came the weaving of woolen scarves and blankets, linen tablecloths, and so forth. Most complicated were the elaborate aprons for Sunday best.

Thirty years ago in rural Greece, much had changed but not all. People wore store-bought, factory-made clothing of cotton for daily wear, at least in summer. But traditional festive outfits and all the household woolens were still made from scratch. It takes several hours to spin with a hand spindle the amount of yarn one can weave up in an hour, so women spun as they watched the children, girls spun as they watched the sheep, both spun as they trudged or rode muleback from one village to another on errands (fig. 1.1). The tools and materials were light and portable, and the double use of the time made both the spinning and the trudging or watching more interesting. In fact, if we reckon up the cleaning, spinning, dyeing, weaving, and embroidering of the wool, the villagers appeared to spend at least as many labor hours on making cloth as on producing the food to be eaten—and these people bought half their clothing ready-made!

Figure 1.1. Seventeenth century woodcut of women in the Balkans spinning while traveling. Spinning was such a time-consuming yet simple and necessary job that women frequently spun thread while doing other things.

Records show that, before the invention of the steam engine and the great factory machines that it could run, this sort of distribution of time and labor was quite normal. Most of the hours of the woman’s day, and occasionally of the man’s, were spent on textile-related activities. (In Europe men typically helped tend and shear the sheep, plant and harvest the flax, and market any extra textiles available for cash income.)

“So why is it, if women were so enslaved by textile work for all those centuries, that the spinning jenny and power loom were invented by a man and not a woman?” A young woman accosted me with this question after a lecture recently.

“Th[e] reason,” to quote George Foster, writing about problems in pottery making, “lies in the nature of the productive process itself which places a premium on strict adherence to tried and proven ways as a means of avoiding economic catastrophe.” Put another way, women of all but the top social and economic classes were so busy just trying to get through what had to be done each day that they didn’t have excess time or materials to experiment with new ways of doing things. (My husband bought and learned to use a new word-processing program two years before I began to use it, for exactly these reasons. I was in the middle of writing a book using the old system and couldn’t afford to take the time out both to learn the new one and to convert everything. I was already too deep into “production.”) Elise Boulding elaborates: “[T]he general situation of little margin for error leading to conservatism might apply to the whole range of activities carried out by women. Because they had so much to do, slight variations in care of farm or dairy products or pottery could lead to food spoilage, production failure, and a consequent increase in already heavy burdens.” The rich women, on the other hand, didn’t have the incentive to invent laborsaving machinery since the work was done for them.

And so for millennia women devoted their lives to making the cloth and clothing while they tended the children and the cooking pot. Or at least that was the case in the broad zone of temperate climates, where cloth was spun and woven (rather than made of skins, as in the Arctic) and where the weather was too cold for part or all of the year to go without a warming wrap (as one could in the tropics). Consequently it was in the temperate zone that the Industrial Revolution eventually began.

The Industrial Revolution was a time of steam engines. Along with the locomotive to solve transportation problems, the first major applications of the new engines were mechanizations of the making of cloth: the power loom, the spinning jenny, the cotton gin. The consequences of yanking women and children out of the home to tend these huge, dangerous, and implacable machines in the mills caused the devastating social problems which writers like Charles Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, and Elizabeth Gaskell (all of whom knew each other) portrayed so vividly. Such a factory is the antithesis of being “compatible with child rearing” on every point in Judith Brown’s list.

Western industrial society has evolved so far that most of us don’t recognize Dickens’s picture now (although it still does exist in some parts of the world). We are looking forward into a new age, when women who so desire can rear their children quietly at home while they pursue a career on their child-safe, relatively interruptible-and-resumable home computers, linked to the world not by muleback or the steam locomotive, or even a car, but by the telephone and the modem. For their part, the handloom, the needle, and the other fiber crafts can still form satisfying hobbies, as they, too, remain compatible with child watching.

Spinning and weaving were such common household activities for millennia that everyone undoubtedly knew how they worked, whether ever performing the actions or not. But now that factory machines have taken over these jobs, most Americans have engaged in weaving only as a childhood game—such as weaving little potholders out of the stretchy loops in a kit—and have never encountered spinning. A brief description of these basic processes is thus in order.

Weaving cloth requires thread of some sort, and thread is made from fibers, so we must begin with the fibers.

Imagine yourself with a handful of coarse fibers, or better yet, go get some. Not cotton: cotton hairs are extremely short and fine so you can’t see how they behave. (They are also not easy to spin for these reasons.) Imagine instead a hank of wool just as it comes off the back of a sheep or goat; you may have seen it stuck to the fence of a cage at the zoo. Or take the long, coarse fibers from a rotted plant stem or from a piece of old frayed rope or twine. (Rope used to be made chiefly from hemp, the species to which marijuana belongs, but now it is usually made from synthetics, which are slippery and therefore hard to work with.)

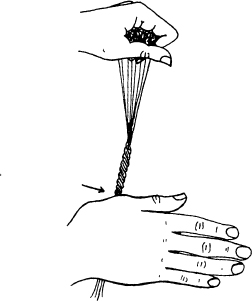

To make thread out of these fibers, you must twist them together longways a few at a time. Although each individual fiber is weak, twisting a number of them together can make a thread that is quite strong. An easy way to do this is to take a small bunch of fibers and roll one end down your thigh with the flat of your hand while holding the other end tight (fig. 1.2). Thus one end gets twisted with respect to the other end, locking the fibers together in the process.

Figure 1.2. Fibers will lock into a strong thread when twisted tightly together. A simple way to make a short thread is to hold the ends of some fibers in the left hand and roll the other end of the bundle down one’s thigh with the flat of the right hand.

If the fibers you begin with are also very long, that may be all you have to do. Hemp, for instance, grows twelve feet high, so you can make a twelve-foot string by doing nothing more than adding twist to the natural fibers. Flax, which gives the fine material we call linen when it is processed, grows to four feet, while silk fibers, which are unwound from the cocoon of a special species of moth, may be as much as a thousand yards long (and incredibly thin). But most fibers are not that long. Wool is at best only a few inches in length and usually much shorter; cotton is shorter still. So we need some way to make thread longer than any one single fiber, extending it as long as we please.

To accomplish that, imagine overlapping the end of one bundle of fibers over the ends of the previous group before adding the twist that locks them together. But you can see that we will get lumpy spots at the overlap and thin spots in between. (Some ancient thread is actually made that way.) What we really need is a way to keep a constant trickle of overlapping fibers flowing into the thread as we make it, instead of adding them in discrete bunches. To do this, we need some preparation and a simple tool, the spindle.

First, the fibers you draw from must be loose and not tangled together so you can get the exact amount you need at all times. Otherwise you will suddenly find you have pulled a big clot of them all at once—or worse, gotten too few somewhere, so the thread gets too thin and breaks.

There are two basic ways of arranging the fibers for spinning, as you loosen them: laying them parallel to each other or encouraging them to lie every which way in a fluffy mass (this is practical only with fairly short fibers). You can make them sit parallel by combing them, much the way you comb your hair to get the tangles out. Then you get a very strong thread (called worsted) that is also very hard to the touch, because it has no fluffiness. The fibers all are packed in close, lying right next to one another as they twist. Men’s wool suits today are usually made of worsted thread, for long wear.

If you want softness, however, you can use carding paddles to loosen the tangles in the fibers without actually combing them. These flat boards with handles have lots of little bent teeth to pull the fibers apart so they lie in all directions. (The name comes from the Latin word for a thistle, carduus, because in ancient times the teeth of thistles were set into boards for fluffing fiber.) The process of carding is much like teasing your hair to make it fluffy. The problem with yarn from carded fiber, however, is that it is rather weak and breaks easily. Modern knitting yarns are almost invariably carded, and they can afford to be because the knitted loops make the cloth stretchy enough to offset the relative weakness of the yarn. Sweaters knitted from these carded yarns feel soft and even spongy.

Once you have your fibers prepared, you are ready to spin. The crudest way, and probably the oldest, is the one we have mentioned: taking a small bunch of fibers and rolling one end down your thigh with the flat of your hand while holding on to the other end. But to get a constant stream of fibers flowing into the thread as you make it, you need one hand to hold the prepared fibers, another to add them to the thread, a third to keep twisting (the core operation), and a fourth to hold the finished thread—because if you let go of the new yarn at this stage, it will instantly ball up in a snarl like an angry rubber band and then start coming apart. Time for some tools: We don’t have four hands.

A spindle is basically just a stick, usually about a foot long.

When the end of the new thread has been attached to the tip of the stick, turning the stick will force the end of the thread to turn, too, adding twist to the fibers to make the thread. But when some thread has been finished, it can be wound around the stick to keep it from tangling while still more is being spun. Thus the tool that twists is at the same time the tool that holds. That reduces the needed hands to three.

How to get it down to two? One hand must always be used for the crucial job of adding the fibers at a controlled rate into the new thread, while somehow the spindle must be kept turning and the fiber supply must be held near.

One solution is to lay the fiber supply down on the ground, turn the spindle with one hand, and use the other to flick the fibers a few at a time into the growing thread. This is how ancient Mesopotamian women did it, as well as rural women today in the Sudan. (It is practical if and only if the fibers are quite short—less than a couple of inches long.)

The other solution is to hold the fibers and drop the spindle—after giving it a quick flick to start it spinning like a top (fig. 1.3). It hangs in the air like a yo-yo, whirling merrily on its thread, while the spinner uses one hand to hold the unspun fiber and the other to control the feeding of the fibers into the twist. When the new thread gets so long that the spindle reaches the ground, you have to stop and wind everything up on the spindle shaft and then start the spindle twirling again in the air. This is the way European peasants spin, and apparently always have. It has the advantage of being entirely portable since nothing has to be laid down. In fact, I have seen Greek village women spinning quite handily while riding sidesaddle on muleback. In order to be able to carry a big supply of raw material, one can bind the prepared fiber to a long stick or board, called a distaff (from an old word dis-, meaning “fuzz, fiber,” plus staff, a fuzz-stick).

Figure 1.3. Woman spinning with a drop spindle, depicted on a Greek vase of ca. 490 B.C.

Back in the Neolithic era people discovered that to reduce wobble as the spindle turns and to prolong the spin it is helpful to add a little flywheel—a small disk called a spindle whorl. Spindles are usually wooden; whorls are most often of clay. But one can use an apple, a potato, or a rock for the whorl if nothing else is available. Contrary to popular assumption, it doesn’t have to be perfectly round as long as the spindle shaft goes through the very middle of it.

Spinning this way is slow, but far faster than rolling the thread on the thigh with no spindle. Early in the Middle Ages, however, a new invention appeared: the spinning wheel. Just who invented it is still unknown, although an old Chinese device for winding thread may have been the inspiration. The foot-powered spinning wheel allowed people to spin about four times faster than with the dropped spindle, so it was much in demand. But the principle is exactly the same as with a hand spindle: Pull fibers, twist them, and wind up the thread. Finally in the late eighteenth century, early in the Industrial Revolution, a man named James Hargreaves invented a mechanical spinning machine (later nicknamed the spinning jenny) because he was distressed at how hard his wife and daughters had to work to spin their increasingly large quotas of thread for the new power looms. The women in his family were delighted, but his neighbors became fiercely jealous of the “unfair” competition and ran him out of town after wrecking his first machine.

To keep the thread from untwisting when it is taken off the filled spindle, the most efficient remedy is to ply the thread. The word comes from French plier, meaning “to bend,” because if you take a spun thread, bend it in half, and let go, the two halves will briefly twist around each other and leave you with a nice thread of twice the thickness that will no longer try to come undone. Try it. (The same can be accomplished by twisting two separate threads together in the opposite direction from that in which they were spun. This is the normal way to do it.)

Spinning, incidentally, is a very restful activity. That is a good thing, because it takes an enormous amount of time to make thread by hand. Like knitting, it is pleasantly rhythmic and can be done sitting down, with no physical exertion, just patience.

Once enough thread has been made, weaving the cloth can begin. Weaving consists of interlacing two sets of threads at right angles to each other. But because thread is very floppy, like spaghetti (unlike the materials that mats and baskets are made of), it is almost impossible to weave the one set of threads through the other without one group’s being held down tight—that is, putting tension on one set of threads. The set that is pulled tight is called the warp, and the frame that holds the warp fast is known as the loom. The second set of threads, which needs to be interlaced into the first, is called the weft (an old past tense of the verb weave—that is, “what has been woven in”). The enterprising reader can take a few short lengths of string, lay half of them out parallel on a table, and try weaving the other half into them at right angles. The problems will become clear immediately.

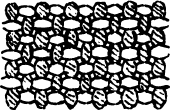

In the simplest weave, called plain weave, each thread of either set goes over one and then under one thread of the opposite set (fig. 1.4). You can see cloth of this sort in any household; simple items like sheets, pillowcases, and handkerchiefs are still made this way. (If you have never thought before about the structure of cloth, take a close look at a sheet or handkerchief right now.) It is also possible to weave various patterns into the cloth by having the weft go over and under different numbers of warp.

Figure 1.4. In the simplest weave (plain weave or tabby), each thread passes alternately over one and then under one thread of the threads at right angles to it.

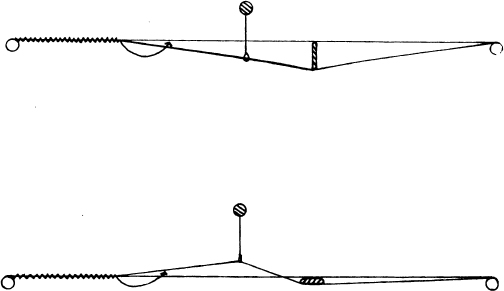

To make these structures—to weave—somehow one has to push the weft under some of the warp threads but over others on the loom. One can do this the tedious way, using a needle to take the weft over or under one little thread at a time, row after row. (This technique is known as darning and is still used as a way to mend socks by those who don’t just throw holey socks away.) Or one can try to lift at one swoop all the warp threads that have to be gone under, leaving in place all the ones that the weft must go over (fig. 1.5). This massive lifting forms a little passageway called a shed (in a vertical loom it looks like the double-pitched roof of a toolshed slanting off to either side), and through this passage the weaver can insert a whole line of weft at once.

How to raise the selected warp threads so nothing gets tangled up? That is not an easy problem. The normal way is to pass each thread through a separate little loop, a heddle (fig. 1.5), in the middle of the loom, and the heddles in turn are tied to bars above the warp (the heddle bars). The warp threads can then be controlled by raising the loops in large groups by means of the bars, much the way the sustain pedal on a grand piano raises a whole row of dampers at once, although the dampers (like heddles) can also be raised one at a time.

Figure 1.5. Diagram of how the warp threads, stretched between two beams (hollow circles), are separated into two alternating sheds (openings) to allow the weft to be inserted. Top: The weft (arrow) is passed through the shed formed by using a shed bar (hatched oblong) to depress every second thread—i.e., half the warp. Bottom: The weft (arrow) goes through the opposite shed formed by raising the same half of the warp with heddle loops attached to a heddle bar (hatched circle). To orient this diagram for a vertical loom, rotate it ninety degrees (clockwise for a warp-weighted loom, counterclockwise for a tapestry loom).

In fact, it seems to have taken several millennia of darning the weft in at a snail’s pace before some genius figured out the principle of the heddle—apparently in the Neolithic (about 6000 B.C.?), somewhere in northern Iraq or Turkey. From there the idea must have spread slowly to Europe, to the Orient, and eventually by boat to South America. It is such a difficult concept that it may have been invented only once. But it is what made weaving an efficient process.

What, then, is the history of this relationship between women and textiles? When did women begin to take up and develop the fiber crafts? How did women and their special work affect society, and how did the societies affect them? These interactions will form the story of this book.

1Notice Brown’s stipulation that this particular division of labor revolves around reliance, not around ability (other than the ability to breast-feed), within a community in which specialization is desirable. Thus females are quite able to hunt, and often do (as she points out); males are quite able to cook and sew, and often do, among the cultures of the world. The question is whether the society can afford to rely on the women as a group for all of the hunting or all of the sewing. The answer to “hunting” (and smithing, and deep-sea fishing) is no. The answer to “sewing” (and cooking, and weaving) is yes.