chapter three

THE PRISONER’S DILEMMA, although thought-provoking, is a little artificial. Only two players who will never meet again and who have no way of communicating: it hardly seems any more of a model for the world around us than MarketThink does. But the forces at work in the prisoner’s dilemma turn out to be at work in more complicated situations too; and co-operation can be even more difficult to achieve in situations involving many actors.

The prisoner’s dilemma has a number of key features.

1. Each player has an unconditional best choice: Player A’s best choice is the same, no matter what choice Player B makes.

2. Each player has an unconditional preference regarding the other’s choice: Player A wants Player B to make a particular choice, and that choice is the same regardless of the choice that Player A makes for himself.

3. These two preferences go in opposite directions: the choice that A prefers to make is not the choice that she or he prefers B to make.

4. Both players are better off if both make their own unpreferred choices than if both make their own preferred choices.1

So we could say that a multi-player prisoner’s dilemma occurs when a number of factors are in place.

1. Each player has an unconditional best choice: each player has a single preferred choice, no matter what the others do.

2. The best choice is the same for each player.

3. Each player has an unconditional preference regarding the others’ choice: there is a choice that each player hopes all the others will make, regardless of what choice that player personally makes.

4. These two preferences go in opposite directions: the choice that each player prefers to make is not the choice that the player prefers others to make.

5. If enough people reject their unconditional best choices, and instead choose their unpreferred alternatives, each is better off than if all of them had chosen their own unconditional best choice.

These multi-player prisoner’s dilemmas are also called free-rider problems, “tragedies of the commons,” and public goods problems.

This story shows the logic of the prisoner’s dilemma at work in a setting that involves fifty-one people instead of only two.

It is a sunny morning, and Jill decides to walk to work across Whimsley Park. Before she reaches the park she visits a local coffee shop and picks up a double-double to go. She drinks the coffee as she walks. Halfway across the park Jill drains the last of the coffee. She looks around, but sees no garbage bins in sight. She is left holding the paper cup and has a decision to make, with two choices.

Does she drop the cup in the park, or does she carry it to work and put it in the bin there? As a good resident of Whimsley, Jill takes a methodical approach to her decision-making: she assigns numbers to the costs and benefits that may accrue to her as a result of her decisions.

In the case of Jack and Jill’s divorce, it was fairly easy to think of the outcome in terms of numbers, because we were looking at money. In this case no money is involved, but thinking numerically can still help to clarify things. Let’s listen in to Jill’s thoughts as she wonders what to do with the cup.

• I enjoy walking across the park. It is a meditative time for me, and if the park is clean I get a benefit, say, of 60 points.

• Unfortunately, the presence in my hand of this empty coffee cup disturbs my reflective frame of mind. If I carry the cup out of the park, the irritation will cost me 5 points.

• I enjoy the pleasant surroundings of the tree-lined green park, and my enjoyment of the park would be lessened by the presence of litter. However, just one piece of litter makes very little difference: almost none in fact. So dropping the cup in the park does not make much difference. It cuts into my benefit by just 1 point.

If Jill carries the cup out of the park, she gets 55 points, but if she drops the cup she gets 59 points. So Jill drops the cup and continues her walk. The irritation of the extra litter costs her less than the irritation of carrying the cup to work.

But just as Jack was not the only person to change shopping habits, Jill is not the only person to walk across Whimsley Park. For the sake of simplicity (this is Whimsley after all), let’s imagine that 50 other people make the same walk, and that each of them makes the same analysis of their costs and benefits as Jill did. Let’s also assume, just to make the arithmetic easier, that the cost imposed by each successive cup dropped is the same: 1 point.

For each person, the “best choice” is the same as Jill’s: drop the cup. But where does this leave them? Each of them will have to face 51 cups drifting around the park, while getting the benefit only of dropping their own cup. They now get only a measly 9 points (60 -51) in crossing the littered parkland, whereas if they had each carried their own cup out of the park they would have enjoyed the walk to the tune of 55 points.

They have all taken a decision that would seem to have left them, individually, better off, yet they are each, individually, worse off than they would have been had they taken the old advice “do as you would be done by.” Just as in the case of the divorce, perfectly good choices have become tangled, producing bad outcomes. Choice and preference are out of alignment, and externalities have produced a bad equilibrium.

Just as in Jack and Jill’s divorce, not only are the participants worse off as a group, but also each and every one of them is worse off than if all the people involved had made the other choice. Jill and the others crossing the park all have freedom of choice, and each made the best choice under the circumstances, but each individual ends up being unhappy with the outcome.

To show how free-riding works, we can use a graph to indicate Jill’s individual benefit, depending on the number of others who are good citizens and carry their cups out of Whimsley Park (see FIGURE 4).

The two lines on the graph show the different outcomes of choosing to carry the cup or choosing to drop it and litter the park. The left-hand side of the graph shows Jill’s points when everyone else drops their cups in the park. The right-hand side shows her points when all others carry their cups out of the park. In the graph, a high number of points is good – it represents a high benefit to Jill. All the way across the graph, the line for dropping the cup is above (preferable to) the line for carrying – indicating that Jill is better off to drop her cup than to carry it out, no matter what percentage of other people carry their cups out. But, as we know, the story does not end there.

The low values on the left-hand side of the graph reveal that Jill will pay a heavy price for the messy park regardless of what she does. The actions of others have cut the enjoyment she gets from the park from 60 points down to only 10. However, if she drops her cup she will lose only i more point, leaving her with a benefit of 9 points. If she carries her cup out of the park, she will lose 5 more points, leaving her with only 5 points.

FIGURE 4. Jill’s best choice. No matter what others do, Jill’s best choice is to drop her cup (bold line). The black square represents the equilibrium outcome.

If everyone else carries their cups out of the park, as the high values on the right-hand side of the graph show, Jill and the others will be pretty happy with the outcome because of the clean park. But, again, Jill can improve her own outcome by littering. If she carries the cup out, she pays a price of 5 points; if she drops the cup, she pays a price of only 1 point; so again her best choice is to litter.

The right side of the graph has higher values than the left side, meaning that the outcome to Jill for carrying along with everyone else (bottom line, right-hand side) is better than the outcome if she and everyone else drop their cups (top line, left-hand side). And this introduces the basic element of the problem with individual choice in such a situation: it leaves everyone worse off.

• Whatever other people are doing, the outcome is always better for Jill if she litters than if she carries. (The drop-cup line is always above the carry-cup line.)

• The more players litter, the worse the outcome for each of them. (Both lines slope down, right to left.)

• The outcome is better, for Jill and for everybody else, if they all carry, than if they all litter. (The carry line on the right-hand side is above the drop line on the left.)

Littering is an example of free-riding. As in the prisoner’s dilemma, the problem arises from how the best choice for each actor alters the outcome for the others. Jill’s decision to drop her cup is an individual decision, but it has an unavoidable impact on each of the other people who cross the park: it has an externality.

In the case of Whimsley Park, the bad effect of each individual decision is small. From a selfish point of view, the best thing that any one person can do is to enjoy the scenic park created by other people’s good behaviour, but not behave in such a fashion themselves: that is, to get a free ride on others’ good behaviour. However, the bad effects of those choices accumulate. The end result is that, as in Jack and Jill’s divorce, the bad effects outweigh the good, and there is nothing that any one individual player can do about it. The structure of the problem encourages bad outcomes.

The root of free-riding is that the cost of carrying the cup is private, while the cost of dropping the cup is public: it is shared among all those who cross the park. For this reason it is also common to refer to free-rider problems as “public goods” problems. A public good does not have to be physical. It can be anything that is, like the litter-free nature of Whimsley Park, inherently shared.

In the free-rider problem any one person’s choice has only a small effect on others’ outcomes, but because these small effects are shared among everyone, they accumulate and become significant. In the prisoner’s dilemma the effects of A’s choice on B, and vice versa, are so large that they dominate even though only one other person is playing.

Examples of the free-rider problem are everywhere. Community health provides some of the most familiar examples. It is best for a community if all children are vaccinated against common infectious and dangerous diseases, but there are known risks with some vaccinations, such as the one for whooping cough. The best outcome for any one family would be for everyone else to be vaccinated, so that whooping cough is not a problem, while their own children do not get their shots and so avoid the dangers of a bad reaction. If vaccination were left to individual choice, the most likely outcome is that the level of vaccinated children would be insufficient to keep the infectious diseases out of our communities. As a result, in many countries vaccinations are made compulsory – individual choice is removed – and community health is better as a result.

The use of antibiotics presents a similar problem: overuse leads to the presence of resistant strains of the diseases that antibiotics are meant to fight. Yet when an individual parent is faced with a sick child whose sore throat may be either the result of a bacterial infection treatable by antibiotics or a viral infection against which antibiotics are useless, the wise choice is to request antibiotic treatment immediately rather than force the child to wait through several painful days for test results showing whether the infection is actually bacterial. While the vaccination problem has been resolved by removing individual choice, the problem of antibiotic overuse persists.

Economist and philosopher Amartya Sen makes the same point in the context of malaria prevention in tropical countries:

I may be willing to pay my share in a social program of malaria eradication, but I cannot buy my part of that protection in the form of a “private good” (like an apple or a shirt). It is a “public good” – malaria-free surroundings – which we have to consume together. Indeed, if I do somehow manage to organize a malaria-free environment where I live, my neighbour too will have that malaria-free environment, without having to “buy” it from anywhere.2

Although the graph showing the walk through Whimsley Park (Figure 4) and the table of the prisoner’s dilemma (Figure 2) look quite different, they really show the same information.

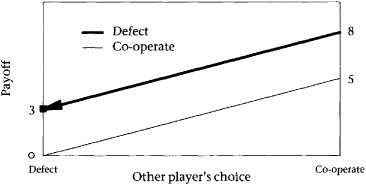

Figure 5 presents the prisoner’s dilemma in graph form. The lines moving across the graph are for clarity only: the only places on this graph that have real meaning are at the left-hand side (where the other person is defecting) or at the right-hand side (where the other person is co-operating). The choice is to co-operate (bottom line) or to defect (top line). The defect line is above the co-operate line at both sides of the graph, showing that defecting has a higher payoff than co-operating no matter what the other person chooses.

FIGURE 5. The prisoner’s dilemma as a graph. The black square is the equilibrium outcome.

If both people defect, the outcome is the top line on the left side. This is the equilibrium, and it is marked by a black square. On the other hand, if both people co-operate, the outcome is a value of 5 points for each person: the lower line on the right-hand side of the graph.

The outcome can be thought of as “sliding down the top line” to the equilibrium. Imagine the players making their choices in sequence. The first player, realizing that the defect line is the best choice no matter what the other player does, chooses to defect. From the point of view of the second player, this has the effect of sliding the decision over to the left side of the graph. The second player also chooses to defect (the top line), fixing the outcome at the equilibrium.

Some of the clearest examples of free-riding in the real world arise in our treatment or management of the environment – which is not surprising, given that the environment is a shared resource. In this context the problems are often referred to as “the Tragedy of the Commons” after a 1968 article by Garret Hardin in the prestigious magazine Science. The public good that is depleted in his illustration is a common grazing ground, and individual villagers have a choice of whether to add an extra head of cattle to the commons. The analysis is identical to that of Whimsley Park – it is to each villager’s individual advantage to add cattle, but when all of them do this the commons gets overgrazed, and everyone suffers.

Technological advances mean that large fishing fleets can now catch so many fish that the stocks cannot be naturally replenished. Like many countries, Canada has well-defined fishing boundaries, but the fish know nothing of such boundaries and cross into international waters all the time. Ocean fish stocks are therefore a “commons” or public good accessible to anyone.3

In the long run it might be better for all fishing countries to cut back on the amount of fish they catch rather than to deplete the fish stocks by overfishing. But it is better for any given country if everyone else cuts back while that country avoids the private cost of reducing its own catch. The externality is that those who overfish today are running down the stock of fish for other fishers and for future generations, but those who refrain have no reason to believe that the fish they spare will survive the nets of other fleets. For each fishing ship, and for each country, the problem is an exact analogue of Whimsley Park: no matter what others do, their best reply is to collect all the fish they can.

The end result – the equilibrium – is just what we would expect: the depletion of the cod and turbot stocks off Newfoundland has led to international disputes with Spain and the closure of entire fisheries. At the other end of the country the disputes have been with the United States rather than Spain, and the species of fish is the salmon rather than the cod and turbot, but otherwise the story is much the same.

The story has been repeated in many other parts of the world. The Rome Consensus on World Fisheries adopted by the 1995 UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Ministerial Conference on Fisheries stated that “additional actions are urgently required” to eliminate overfishing and to rebuild and enhance fish stocks. It also stated, “Without such action, further declines will occur in the 70 per cent of the world’s fish stocks which are now regarded as fully exploited, over exploited, depleted or recovering.”

Realizing how the temptation to free-ride encourages overfishing helps to avoid the good-guy/bad-guy oversimplification of the debate. The fish stocks are not being run down because there are evil people who enjoy driving fish species to extinction, or even necessarily because there are people who selfishly don’t care about the long-term sustainability of the fisheries, but because no individual player acting alone can significantly improve the overall outcome. Market-Think would argue that the solution is to establish clear property rights, but fish do not respect such rights and will swim across what-ever boundaries are drawn. Even if no one would prefer the fish stocks to be depleted, for each country involved the best reply to the situation is to overfish. The more the country depends on fishing, the stronger the short-term incentive to overfish.

Littering is, of course, a simple form of pollution, and pollution on a larger scale essentially represents the same problem as dropping a coffee cup in Whimsley Park. The cost of any one company reducing pollution is borne privately, while the benefits of a clean environment are shared by everyone. The problem is made more severe than that of Whimsley Park because it is not only, or even mainly, companies that bear the cost of a polluted environment, but people in general. Indeed, companies per se do not care about the environment except insofar as it has an impact on their operations. If factories built around a lake need a source of clean water and also put waste into the lake, it might be better for all companies if they treated their waste before expelling it into the lake than for all companies to have to clean the water they take from the lake. But it would be slightly better still for any one company if all the other companies treated their waste while that company avoided the private cost of treating its own.

It is not required that companies be run by evil cigar-smoking industry barons for pollution to take place. One economics textbook describes the issues facing any one company:

When a firm pollutes a river, it uses some of society’s resources just as surely as when it burns coal. However, if the firm pays for the coal but not for the use of clean water, it is to be expected that management will be economical in its use of coal and wasteful in its use of water.

Even well-intentioned companies are put in a position where their best reply to the actions of others is to pollute. It is the structure of the situation that creates the problem, and the structure that must be changed.

Environmental free-rider problems abound. Here are just a few others.

OZONE LAYER. The ozone layer is a “public good” or “commons.” It is only to be expected that, if it is left up to individual countries to recognize their long-term interests and refrain from damaging the ozone layer, the result will be a failure – not because countries are too stupid or too short-sighted to act in their own interests, but because any one country contributes only a little to the problem. Each country’s own interest is best served if others restrain themselves, while that country continues using the chlorofluorocarbons that damage it. End result: big holes in the ozone layer.

CLIMATE CHANGE. Why should any one country spend the money to decrease its emissions of carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse gases,” when that action will have only a limited effect and other countries may renege? End result: global warming.

ACID RAIN. The bad effects of acid rain are inherently shared, while the benefits of acid-rain-producing technologies are private. End result: dead lakes.

What can be done to get out of the problems of environmental mismanagement?

There are ways of changing the structure of free-rider situations to encourage better outcomes. One of the most obvious is to change the payoffs by penalizing free-rider behaviour or, what amounts to the same thing, rewarding co-operation.

The incentives to free-ride or to co-operate are not determined by the absolute value of the payoffs, but by the differences between the payoffs for free-riding and co-operation. Punishment lowers the payoff for free-riders, while reward raises the payoff for co-operators. Both aim to tip the balance between the choices: to change the structure of the game to favour the co-operative choice over the free-riding choice.

Penalizing those who drop litter is one way of maintaining a clean park. Jill may know that if she is caught dropping her coffee cup she will be fined, or at least embarrassed by a reprimand, and this possibility makes the cost of dropping the cup a bit higher – perhaps high enough to shift the balance and keep the park clean.

Jill may choose to be subject to fines as long as it helps to improve the state of the park: that is, as long as the other coffee drinkers are subject to fines as well. There is no contradiction in this: it makes perfect sense for Jill to drop her cup on the way to work, but also to vote for a bylaw to ban littering and introduce park patrols. Wise people often take steps to eliminate choices that they know will lead to bad outcomes. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus wanted to hear the song of the sirens and yet knew that he would not be able to resist its lure. His solution was to order himself tied in advance to the mast of his ship so that when he became vulnerable to the song he would be unable to exercise his freedom of choice.

Consider this comment from a hockey player in the times when wearing helmets was not mandatory.

It’s foolish not to wear a helmet. But I don’t – because the other guys don’t. I know that’s silly, but most of the players feel the same way. If the league made us do it, though, we’d all wear them and nobody would mind.4

This player is saying that hockey players would be better off if they gave up the choice of wearing helmets by giving an external group (the NHL) the right to make this restriction. Likewise, removing the matter of choice can improve Jill’s outcome as long as other people’s choices are restricted too, and the cost to her is that she carry her cup out of the park.

Warfare provides an archetypal example of removing choice to improve outcomes in the face of free-riding. Economist David Friedman states:

In modern warfare, many soldiers don’t shoot and many who do shoot don’t aim. This is not irrational behaviour – on the contrary. In many situations, the soldier correctly believes that nothing he can do will have much effect on who wins the battle; if he shoots, especially if he takes time to aim, he is more likely to get shot himself....

The problem is not limited to modern warfare. It is a thousand years ago. You are one of a line of men on foot with spears, being charged by a mass of men on horseback, also with spears. If you all stand, you will probably break their charge and only a few of you will die; if you run, most of you will be ridden down and killed. Obviously you should stand.

Obvious – and wrong. You only control you, not the whole line. If the rest of them stand and you run, you run almost no risk of being killed – at least by the enemy. If all of them run, your only chance is to start running first. So whatever the rest are going to do, you are better off running. Everyone figures that out, everyone runs, and most of you die.5

On landing in England in 1066 William the Conqueror is supposed to have burned the boats that brought his army there. This removed the “choice” for his men to flee and ensured that his soldiers would fight harder. End result: military victory and a better chance of survival for each soldier.

Friedman also suggests that one role of the neat geometric formations and bright uniforms of European soldiers in Napoleonic times was to make monitoring of free-rider behaviour easier: individual soldiers found it harder to unobtrusively fall to the rear.

Once this tension is understood, we can see through some of the standard arguments concerning consumer preferences. Journalists sometimes point out that the very people who oppose the building of a Wal-Mart or some other big-box store sometimes end up shopping there after it is built, as if this shows that the protesters changed their minds, or that when it comes down to it they may even like Wal-Mart. Just because they shop at Wal-Mart does not mean that Wal-Mart is “popular” with them, any more than the littered state of Whimsley Park shows that the people passing through it want it to be an unsightly mess. Just as Jill can enjoy a clean park and still drop her coffee cup rather than carry it, so consumers may find it makes sense to shop at Wal-Mart even if they wish it had never been built.

Historically, environmental activists and economists have not always got along particularly well. Generally, economists tend to phrase problems in terms of individual incentives and solutions while environmentalists tend to think that people can move beyond such short-sighted thinking. Oddly enough, however, you can open any economics textbook and find a perfectly good explanation of why “leaving it to the market” leads to bad environmental outcomes.

The belief that markets, as constructed, fail to properly conserve environmental resources was reflected in a 1997 “Economists’ Statement on Climate Change” calling for serious measures to limit the emissions of greenhouse gases and signed by no fewer than 2,500 economists. Paul Krugman, a thought-provoking economist and an innovator who has helped to develop new ways of thinking about international trade, was one of the original signatories of the statement. In defence of his profession he points out:

Economists generally believe that a system of free markets is a pretty efficient way to run an economy, as long as the prices are right – as long, in particular, as people pay the true social costs of their actions. Environmental issues, however, more or less by definition involve situations in which the price is wrong – in which the private costs of an activity fail to reflect its true social costs.6

One way of making choices and outcomes align, then, is to require participants to pay for the right to free-ride. If pollution is taxed, firms will be more careful about how much they pollute. An alternative to taxing is for a government to fix a total pollution target and to distribute credits to the members of the industry, an approach inspired by the ideas of Nobel Prize-winning economist Ronald Coase. By letting firms trade these credits rather than trying to impose a uniform limit on all firms, those who have the ability to cut pollution easily have an incentive to cut a lot – the more they cut their pollution, the more they can make by selling their pollution credits to others. Those companies that are less able to cut pollution levels can buy credits from others. As long as pollution can be monitored, and as long as the total target is a realistic one, there is a lot to be said for this approach.

Taxes and credits are not as different as they may seem. Both are an alternative to fixed-limit legislation as a way of tackling the pollution problem. The tax acts like a penalty on the act of pollution (although without the stigma of “breaking the law”), while credits accomplish the same change of incentives by use of the carrot rather than the stick.

Although the concept of pollution credits was originally proposed by Dan Dudek, an environmentalist with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) – and other environmental organizations have joined EDF in supporting the plan – some environmentalists have not welcomed the idea. The critics present strong arguments – for example, that monitoring of pollution is so unreliable that enforcement would be difficult, as in the case of the ocean fish stocks. Other arguments are weaker: for example, the contention that credits place a price on pollution and that “buying and selling” pollution is simply wrong. Environmental scientist Barry Commoner, for instance, calls the plan “an abomination.” He argues, “It legitimizes the production of pollution.” Peg Stevenson of Greenpeace concurs with Commoner’s analysis, saying that pollution allowances “create a right to pollute.”7

Krugman provides another point of view:

It used to be that the big problem in formulating a sensible environmental policy came from the Left – from people who insisted that since pollution is evil, it is immoral to put a price on it. These days, however, the main problem comes from the Right – from conservatives who, unlike most economists, really do think that the free market is always right – to such an extent that they refuse to believe even the most overwhelming scientific evidence if it seems to suggest a justification for government action.8

Just because solutions are based on the market doesn’t make them immoral. On the other hand, just because market-based solutions are not immoral, we cannot conclude that all market-based solutions are good. Suspicion of some of the more prominent market-based proposals is well-founded. For example, many participants at the Kyoto environmental summit in 2000 saw the U.S.-sponsored pollution credits initiative as simply a way in which a state could avoid making any significant commitment to reducing pollution, and they were right. But that was because of the particulars of the plan, not because of the very notion of pollution credits.

Pollution credits have some benefits as a way of tackling particular pollution problems. For instance, they may work well for pollutants such as greenhouse gases and ozone-depleting chemicals, which are distributed globally. Because the impact of these gases and chemicals bears little relation to where they are produced, shifting pollution from one site to another does not make the problem better or worse.

But for other kinds of pollution problems the credits fail to deal with the real issues. Liquid industrial effluent travels only down waterways, and heavy waste such as the mercury from coal-fired power stations does not travel far even if it is emitted from smokestacks. In such cases allowing some companies to maintain or even increase their level of emissions if they can buy credits from those who have implemented anti-pollution measures will lead to the creation of highly polluted “hot spots.” Despite this, in March 2005 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency adopted regulations that used pollution credits to tackle the problem of mercury pollution, arguing, “There is similarity in how these emissions are produced, and there should be similarities in how they are controlled.”9 The use of tradeable credits makes life easier for the companies producing the pollution, but does not tackle the damage inflicted by mercury.

Farmers throughout Canada and other countries are planting more genetically-modified (GM) crops each year, with Monsanto’s Roundup Ready strains, first introduced in Canada, being the most widely used. Roundup Ready canola was the first to be developed, Roundup Ready soy and corn are on the market, and Roundup Ready wheat is under development.

Monsanto advertises its product to farmers by claiming that Roundup Ready crops require less herbicide than do “conventional” crops. The canola or other plant is engineered to be resistant to the broad-spectrum herbicide Roundup (made, of course, by Monsanto). Roundup is good at killing weeds, but cannot easily be used on conventional crops because it would kill them too. When farmers plant Roundup Ready crops, the weed killer kills the weeds and leaves the crop growing healthily. By using Roundup Ready crops, farmers can replace applications of a cocktail of selective pesticides by applications of this single herbicide.

Monsanto puts “Grower success stories” from Canadian farmers on its website to encourage others to adopt the product. For example, Brian Harvey of Durban, Manitoba, reportedly said: “The Roundup did a tremendous job. It wiped out the wild oats and all our other weed problems – wild mustard, wild buckwheat, lambs-quarters, green foxtail and sow thistle. The weed control has been exceptional.”10

Environmental groups argue that farmers are being forced into dependence on Monsanto by the introduction of GM crops. At first sight there appears to be little basis for this claim: after all, no one makes farmers plant GM crops. But with a closer look the claims of environmental groups become more plausible. Just as with Jill and her coffee cup, the reason is that farmers’ actions have externalities: one farmer’s choice has an impact on other farmers.

Herbicides are like antibiotics: overuse can degrade their effectiveness as resistant strains develop. Application of a herbicide gives an evolutionary edge to genes that confer immunity to that herbicide. While small amounts of herbicide are unlikely to prompt a shift in the genetic makeup of weeds, large-scale applications can and do, and the move to replace many different pesticides with a single one (Roundup) only makes that shift happen faster.

Widespread application of Roundup promotes the spread of resistance to that herbicide – the spread of what could be called “Roundup Ready weeds.” Each field of Roundup Ready canola (with its attendant applications of Roundup) slightly accelerates the appearance and spread of resistant weeds.

But for an individual farmer, choosing not to plant Roundup Ready canola is not necessarily a good alternative. Roundup Ready weeds may harm Roundup Ready crops, but they also harm conventional crops. Fields of conventional canola will then be hurt by both Roundup-resistant weeds and weeds that Roundup can control. Meanwhile, Roundup Ready fields will be hurt only by the Roundup-resistant weeds. Roundup resistant weeds are a shared form of pollution or “public bad” that cannot be avoided by any one individual. There is no reason for any one farmer to plant conventional crops, because that farmer will get both kinds of weeds on his or her fields.

The testimony on the Monsanto website may well be misleading, then, especially because it comes from early adopters. These farmers are able to drop their cups in the park, but they don’t have to face the prospect of a littered park because most other farmers do not yet have the same choice. But this does not mean that, once everyone can make the choice, they will all be better off. Although Roundup Ready crops are sold on the basis that they need fewer herbicides than conventional crops do, and while this claim may be true on an individual basis, widespread Roundup Ready adoption may actually increase the long-term need for herbicides.

The same “perverse logic” was apparent decades earlier in the case of another pesticide, DDT, as Edward Tenner points out in his book Things Bite Back: “The more effective a pesticide, and the more widely and intensively farmers apply it, the greater the potential reward for genes that confer immunity to it. In Sweden and elsewhere in Europe and North America, DDT-resistant flies appeared as early as 1947.” In 1944 in Naples DDT was applied to over a million residents of Naples in a campaign to get rid of body lice and thus prevent an incipient typhus epidemic; but, according to Tenner, “By the mid-fifties, only ten or fifteen years after the Naples campaign, body lice in many parts of the world were already unaffected by DDT treatment. So were many farm, orchard, and forest insects in the United States.”11

Reports are already emerging that this is exactly what is happening with the Roundup Ready campaign. One report indicates that total herbicide application on Roundup Ready soy beans in the United States is expanding compared to herbicide use on conventional varieties. As well, according to the report’s author, Charles M. Benbrook: “Intense herbicide price competition, triggered by the commercial success of RR soybeans, has reduced the average cost per acre treated with most of today’s popular herbicides by close to 50 percent since the introduction of RR soybeans. In response farmers are applying more active ingredients at generally higher rates.”12

In areas in which Roundup Ready soybeans are in heavy use, according to Benbrook’s study, all farmers are using more herbicides than in low Roundup Ready-use areas. An individual farmer cannot avoid the need to apply herbicides by shunning Roundup Ready soybeans. In fact, in areas of high Roundup Ready use and in areas of low Roundup Ready use, farmers using conventional varieties (other than organic farmers) may need to apply more herbicides than are farmers using Roundup Ready varieties.

These trends, then, only increase the risk of resistance and ultimately lead to less reliable and more costly systems.13 Given the nature of the problem, the response from Bryan Hurley of Monsanto is less than persuasive: “American farmers have planted 60 percent of this year’s soybean crop, roughly 40 million acres, with bioengineered Roundup Ready seeds. They would not be selecting these seeds if it was not to their advantage.”14

But the story does not end with herbicide-resistant weeds. A second free-rider problem is at work here. Roundup Ready crops spread to other fields where they are unwanted, and become weeds themselves (“volunteers”).

What is a crop in one field is a weed in another field. Crop plants growing where they are not wanted become litter. While use of Roundup Ready crops was limited to a small number of farmers, this was unlikely to be a big problem for any one farmer, but as the use of Roundup Ready crops grows, so too does the problem. In Canada the problem of volunteers is compounded when more than one kind of herbicide-resistant canola is being widely planted. These different canola “cultivars” can exchange genes, leading to “the unintentional origin of plants with multiple resistance to two, and in some cases three, classes of herbicide,” according to a report from the Royal Society of Canada. “Such ‘gene stacking’ represents a serious development because, to control multiple herbicide-resistant volunteer canola plants, farmers are forced to use older herbicides, some of which are less environmentally benign than newer products.”15

Of course, the problem will particularly hurt the growers of organic crops, whose ability to sell their product depends in many cases on it being free of, among other things, genetically modified material.

The best outcome for any one farmer may be for every other farmer to not plant Roundup Ready crops, but to take personal advantage of the crop. This is free-rider behaviour, not free-market choice, and the end result is unlikely to be beneficial for farmers as a whole. Farmers are trapped in the prisoner’s dilemma. They are likely to find themselves in a spiral of increased herbicide costs and increased dependence on Monsanto, all the while making their own free choices.

Cities are intricate webs of interconnected systems. Transport, housing, land-zoning, education, public spaces, and services all connect with each other in myriad ways. Externalities are everywhere, and so we should not be surprised if individual choice and the market commonly lead to bad outcomes. In particular, we can expect the free market to value those aspects of city life that are treated as private choices, and to be responsive to those situations in which money changes hands. At the same time, we can expect the market to undervalue public spaces and other non-commercial aspects of cities, where we cannot express our wants through purchases and where free-riding is tempting.

All of us make tradeoffs in choosing a home, a place to live. Budget, the distance to a workplace or school, and other priorities are all part of this. But within these constraints we do still get to choose the kind of dwelling we live in and the neighbourhoods we move to. As a result, it is common to hear that as long as regulations don’t get in the way, cities will evolve to reflect the preferences of their inhabitants: the market will ensure that we get what we want. Yet there is a deep-seated unhappiness about the shape that our cities are taking – and although some of it is a result of “not in my backyard” thinking, there is much that goes beyond mere selfishness.

Many North American cities are now more suburban than urban, with the perpetual development of new subdivisions on the edge of cities adding ring after ring of new houses. The resulting cityscape has many well-known problems. The diffuse layout makes an effective public transit system impractical and ensures that the city will be car-focused. The same diffuseness makes services expensive and may encroach on valuable surrounding environmental features, including water tables. Hollowed-out cities may lack a viable centre, which can in turn lead to a corresponding lack of public spaces.

But no one made us choose this kind of city, so how does the discontent we see around us fit with the choice made by many people to move into these successive rings of new houses? A professor at the School of Policy, Planning, and Development and Department of Economics at the University of Southern California offers one view of the shape and growth of cities: “The development of neighborhoods by private developers is driven by markets, not by public policy. People are getting the neighborhoods they want. And I trust that competing developers are reading the trade-offs that you and I are willing to make and that those trade-offs include our demand for community.”16

This is the ubiquitous logic of MarketThink: leave everything to individual choice and the market will ensure that we get what we want. But the coffee cup debacle at Whimsley Park shows what is wrong with this kind of argument, and why individual choice may not leave us all in a happy state of mind.

It is often pointed out that, no matter what people say about urban sprawl, the most popular choice for housing remains so-called “green fields” development: new houses in new subdivisions on the edge of the city. Let’s accept that for the moment. But, again, the story of Whimsley Park should tell us that there is always more than one side to a choice, and the decision of where to buy a house is only one of many we make.

By following the trends of home-buying decisions, private developers may be driven by customer choices, but they are also, perhaps, getting a distorted version of what the people want. We all have many different preferences about our cities: in addition to preferences about our houses, we also have a preference for the quality of the air we breathe, the schools we send our children to, the services we get from the city, and the taxes we are prepared to pay to get those services. Perhaps we even have a preference for “green fields” that are actually green and actually fields, or for a city that is small enough to bicycle across. Still, all of these preferences are prone to the principle of free-riding. Jack may like the idea of having both a compact city and a house overlooking green fields, but he cannot choose a compact city by himself so he chooses the house overlooking green fields – and contributes to urban sprawl. Jill might like both low property taxes and a spacious lot, but she cannot by herself keep municipal budgets trim so she chooses the spacious lot – and contributes to a thinly populated city that needs extra school buses and longer sewage pipes. If city councillors rely on house purchases as a measure of our preferences, they will ensure that all those other preferences will vanish into thin air – or, more likely, into thick smog-filled air.

The web of choices can become complicated, and the line between public and private is hard to discern. My new house on the edge of town makes the countryside just a little more difficult for you to reach. If your backyard happens to be close to my balcony, then my “panoramic view” is your loss of privacy. My speedy route to work along a wide road is a dangerous barrier on your child’s walk to school. If, to protect your children from my car and from the other cars speeding along the nice wide road, you drive your children to school rather than letting them walk, then you are adding another car on the road and lowering the number of children walking to school. As more children stop walking, we end up with unsafe empty sidewalks and unsafe crowded roads outside the schools. And I still have to drive through a crowded street because of all the extra traffic. All of this is a result of perfectly reasonable individual choices.

To return to the issue of home-buying: we might all be happier if everyone lived in a smaller house with a smaller yard, but it might be slightly better still for an individual family if its members had a big house and a large yard, while everyone else lived in a smaller house. The urban environment is a shared resource, and the free-rider dynamics of individual choice ensure that this environment will not be treated well by individual choice. End result: sprawling subdivisions, and unhappy city dwellers.

There is more to urban sprawl than this, of course, but it is clear from the structure of the situation that if we leave city development to the free market, it will respect those factors that are private, like big houses for those lucky enough to be able to afford them, and will systematically undervalue those that are shared, like interesting, manageable, and compact cities.

Here is a related urban problem. If everyone took public transit to work, available road space during rush hour in many cities would be increased, allowing everyone to get to and from work more quickly. So why do so many people continue to drive in even the most congested rush-hour traffic? If most people are riding the bus, the best individual choice is to drive your car, because you can move quickly along the empty streets and also avoid the crush and waits of public transit. If most people are driving cars, you would still lose something by riding the bus, because it has to stop to pick up passengers. It is the free-rider problem, and the equilibrium is that everyone takes their car, everyone takes their little piece of the shared resource that is road space at rush hour, the roads become clogged, and everyone takes longer to get to work.

There is more than just transit time to be considered when we choose the freedom and flexibility of car travel as we move around the city. In addition to congested roads, dependence on cars produces bleak parking lots and air pollution. The eyesore of parking lots, like that of litter-strewn parks, is a public “ill” to which everyone is subjected. Pollution is also a shared cost. We can be sure that free individual choice will not get rid of them, even if they are almost universally disliked.

Again, one approach to congestion is to build a system that more clearly focuses drivers’ minds on the cost of precious road space by charging them for it. This is precisely what London, England, mayor Ken Livingstone did starting in February 2003, when London began charging motorists £5 to drive in Central London between the hours of seven in the morning and six-thirty in the evening.17 Every car that drives on a congested street imposes a small cost on all the other road users: a cost that the individual driver is usually not asked to bear, at least alone. Instead the costs are shared among everyone -which means that they add up and, in the end, can easily outweigh the private benefit of driving. They create a trap that catches a lot of unhappy drivers.

With the introduction of a charge, each driver pays a more realistic portion of the cost imposed as a whole on road users. Individual choice remains, but the balance of incentives is tilted to reflect more accurately the true costs and benefits of the decision, including the public costs.

The last 20 years have seen the growth of big-box stores in what have become known as “power centres” around the edge of major towns throughout North America. The result has been the erosion of many downtown areas. The power centres have joined an earlier development, the suburban mall, in pulling commerce ever further away from the centre of cities. Companies such as Wal-Mart, Home Depot, Ikea, and Costco are associated with this trend, and established firms such as Sears and Canadian Tire have followed these newer competitors out to the edge of town, paying them the compliment of imitation.

The growth of power centres and the associated hollowing out of cities have been the focus of many arguments. Many cities, although not all, have taken the view that the success of big-box stores is the voice of consumer sovereignty speaking. To prevent the growth of power centres would be to limit choice, to restrict the freedom not only of the companies wanting to build, but also of the consumers wanting to shop there. As the argument goes, the commercial success of power centres is a demonstration of their popularity, because, of course, no one makes you shop at Wal-Mart. Protesters against big-box stores have focused their efforts on preventing the construction of the stores, accepting that once they are built, there is little that can be done.

But, as the story of Jack and Wal-Mart (chapter i) shows, the success of power centres does not mean what their proponents claim it means. Like Jack, people may shop at them and still end up wishing that they were not built in the first place.

Successful downtowns are public spaces, multiple-use and multiple-owner areas characterized by diversity; and as public spaces, they are vulnerable to free-riding. Jack and the other inhabitants of Whimsley never choose to neglect the downtown area, but once its population slips below a critical point, the whole infrastructure can unravel. City centres are more complex than parks, but we can at least begin to see how a city centre can move from prosperous to decaying without anyone actually wanting it to.

Competition and variety are also public goods: by their nature, neither can be provided by a single store. Jack never explicitly chooses to have a narrower choice of places to shop, and yet he and others like him contribute directly to the problems of the downtown stores.

Of course, individual consumer choices are not the only factors that help to eliminate competition and variety. The story also has a supply-side angle, and that side of the coin is undeniably important. WalMart is a master at exploiting economies of scale, in its use of technology, its placement of stores, and its purchasing power and leverage with suppliers.

When a major store captures a substantial portion of a particular market, a shift occurs in the balance of power between retailer and suppliers. A huge company like Wal-Mart becomes an essential customer for manufacturers, and essential customers can dictate terms to their suppliers. Wal-Mart is able to demand deep discounts from its suppliers. An essential customer’s game of divide and conquer can put suppliers in a prisoner’s dilemma, in which their choices are to sell at wafer-thin margins or to miss out on a large market. Wal-Mart will buy from the supplier that offers the lowest prices – and to win in this competition a supplier may have to cut costs, change its way of operating, move jobs to ever-cheaper Third World sweatshops, and still receive only a slim margin from the sale. If all the suppliers hold out, perhaps Wal-Mart would have to back down and the suppliers could get a better deal, but no matter what the other companies do it is in the short-term interests of each of them to take the deal and sell to Wal-Mart rather than to sell nothing. As a result, the suppliers are trapped.

A similar divide-and-conquer aspect exists in the construction of a big-box store. When big-box stores come looking for land to be rezoned so that they can build their power centres, city councils can be placed in a prisoner’s dilemma. Power centres are located to take consumers from as wide an area as possible – typically at a location accessible from several urban centres. For each city council, the worst outcome is that a power centre will indeed be established – but in someone else’s location. If that happens, the city loses business in its own shops and gains none of the property taxes from the new power centre. It may be best for all cities to prohibit a power centre from going ahead, but it is better for a city to get the power centre than to have it established in a neighbouring area.

While it may also be the case that big-box stores are more economical or efficient than the smaller stores, it is not necessarily so. A recent Canadian example is the construction by Chapters of a large number of big-box bookstores in cities across the country. In bringing about its growth Chapters paid considerable attention to consumer appeal – it brought to Canada the large bookstore model, with in-house coffee shop and comfortable chairs that encouraged customers to linger, not just to buy and go. As a result of its building spree Chapters came to own 70 per cent of the book market in the country.

Book publishers in turn found it essential that Chapters stock their products. In its attempt to dominate the industry from one end to the other Chapters went a step further than even Wal-Mart. It set up its own book distribution service. That branch, Pegasus, distributed books not only to Chapters stores, but also to some of the competitors. Chapters was able to demand, from publishers, deep discounts and favourable policies for returns, and publishers had no alternative but to accept the terms.

Despite these advantages, the reason that Chapters drove so many bookstores out of business was not because the operation was a more successful business model or that economies of scale would sooner or later make bigger stores more efficient and profitable than smaller stores. In fact, in February 2001 Chapters was ignominiously sold to the owners of its major rival, Indigo, following months of rumour and speculation of financial troubles. And by 2004 Indigo itself was moving to devote more of its floor space to goods other than books. Rather, Chapters drove smaller bookstores out of business because its corporate owners had the deep pockets necessary to back investment in the construction of many large new bookstores. It drove publishers such as Stoddart into bankruptcy because they had little choice but to restructure their operations around Chapters’ needs.

The animosity between publishers and Chapters was such that, when the Indigo purchase was confirmed, Allan MacDougall, president of B.C.- based Raincoast Distribution, remarked, “I don’t know how this business could be in any worse shape and still be called a business.... Let’s just say the last 18 months have been the worst in the history of publishing in Canada.”18

The interconnectedness of choices makes cities what they are, and the MarketThink approach of letting a limited number of individual choices (purchasing decisions) drive the growth of cities is bound to lead to bad outcomes. As Jane Jacobs observed over 40 years ago in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it makes no sense to think of the city as “a collection of separate file drawers” because cities present “situations in which a half-dozen or even several dozen quantities are all varying simultaneously and in subtly interconnected ways.”19

Jacobs spends the first three chapters of her landmark book on “The Uses of Sidewalks.” To focus on sidewalks is itself a novel start for a book on cities: they are exactly those places that most city planners miss. Sidewalks are a physical symbol of the externalities and tangled choices that permeate our cities: “A city sidewalk by itself is nothing. It is an abstraction. It means something only in conjunction with the buildings and other uses that border it, or border other sidewalks very near it.” Jacobs does not even talk about what most of us think of as the “purpose” of sidewalks: “Streets in cities serve many purposes besides carrying vehicles, and city sidewalks – the pedestrian parts of the streets – serve many purposes besides carrying pedestrians.”20

The “uses of sidewalks” that Jacobs investigates are safety, contact, and the assimilation of children into the broader adult society. None of these uses has any significant role to play in a market-based look at cities. Each is a public good: we either have busy, occupied sidewalks or we don’t. No one person can buy a bustling city street for themselves. To introduce a market for safety, for example, is to ask for a gated, segmented city. It is in these neglected spaces, at the edge of vision, that the success or failure of cities gets determined. Thinking of cities as a collection of separate problems makes as much sense as trying to understand a liquid by using the ideal gas law (chapter 2). Interactions and tangles are at the heart of the matter; they are not something to be treated as an imperfection or perturbation.

Among her many examples, Jacobs looks at the problem of a city neighbourhood park.21 The usage of the park depends on many factors, including the park’s own design and who is around to use the park and when. This in turn depends on the uses of the city outside the park itself. Furthermore, the influence of these uses is not just the sum of several independent factors, but depends on the particular combination of uses. These uses near the park and their combinations depend on other factors, including the age and variety of building, and the size of blocks in the vicinity.

We have not, then, chosen the cities that we live in at all, at least in the sense that is usually meant. That is, our cities are not the result of any intrinsic preferences. Instead, we are each making many interconnected choices, and that means we are making choices that depend on those of others. Our decisions of where to live, of how to travel, of where to shop – these are not so much expressions of an intrinsic preference as they are best replies to the environment in which we live, shaped by and in turn shaping the actions of others and the future shape of the city. We may not “want” to drive a car to work, but given that most other people do, it is the best alternative available. We may not want to live in a suburban environment, but if that is where good housing is available, at prices we can afford, where people we know are living, and where the new schools are being built, then perhaps it is the best available option. We might not want to avoid the city centre, but if the houses and buildings there are old and rundown, if the streets don’t seem as safe, and if businesses are closing, there is no point in going there.

There are no magic solutions for the problems of modern cities. There are, however, preconditions for success, and one of those preconditions is to understand that if we divide the problem of city development into separate compartments, and open each compartment to a market model of “choice,” we are most likely to end up in a bad place. MarketThink is guaranteed to erode public space and public goods in the city. If we want to find a favourable equilibrium among the many complex games being played in the city, we cannot hope to do so by avoiding collective decisions regarding the type of city we want.

The lessons that Jacobs draws about cities apply more broadly. There are no simple solutions to the problems of individual choice. But if we think about the problems in the right way, and don’t get misled by the false and simplistic promises of MarketThink, we are more likely to find our way to a happy outcome.