chapter seven

NOW FOR ANOTHER GAME, one that is as simple as the prisoner’s dilemma and has as many implications.

Two people are walking directly towards each other along a side-walk, and they are faced with the problem of avoiding a collision. If both of them, from their own perspectives, step to their left or both step to the right, they avoid the collision and are both happy. If one steps to the left while the other steps to the right, they collide. In this game the best choice for each player depends on the choice that the other player makes, and the best outcome happens when both make the same choice: when their choice is co-ordinated. For this reason, the game is called the co-ordination game.

The co-ordination game is like the prisoner’s dilemma in that it involves two people, each of whom has a single choice to make (which way to step) between two alternatives (left or right). In other ways the co-ordination game is the opposite of the prisoner’s dilemma:

• In the prisoner’s dilemma, each player has an unconditional preference: the player prefers the same choice, irrespective of which choice the other person makes. In the co-ordination game each player has a conditional preference: the preferred choice depends on the choice made by the other player.

• In the prisoner’s dilemma, each player has an unconditional preference regarding the choice made by the other player – each player would like the other to co-operate. The preference is not affected by the choice one makes for oneself. In the co-ordination game each player has a conditional preference with respect to the other’s choice: it is affected by one’s own choice.

• In the prisoner’s dilemma, the preferences of the two players go in opposite directions: the choice each prefers to make is not the choice that the player wants the other to make. In the co-ordination game the two preferences go in the same direction: the choice that each prefers to make is the choice that the player wants the other to make.

• In the prisoner’s dilemma, the strengths of the preferences are such that both players are better off if they make their unpreferred choices than if both make their preferred choices: there is a single, predictable, unhappy outcome. In the co-ordination game, there are two equilibria: as a result there are multiple, unpredictable out-comes, which can be more or less happy.

To take a closer look at the co-ordination game, let’s return to the town of Whimsley.

Jack’s nephew Bill, who lives with his own family in Whimsley, is a style-conscious nineteen-year-old, and when we catch up with him he is off to the mall with his friend Adrian. Both of them are looking to buy a pair of sneakers.

In Whimsley, of course, the simplicity of things extends to footwear, and the stores carry only two brands of sneaker – let’s call them “Nike” and “Adidas” – as opposed to the half a dozen or so other brands available in most towns. Still, in the shoe store at the mall Bill and Adrian are confronted with shelf after shelf of footwear. There are liquid-filled shoes with extra bounce, shoes inspired by aerospace engineering (“the technology-packed Nike Shox 664 is the same hoop shoe worn by Vince Carter”), shoes of all kinds of colours and designs – but there are only the two brands.

Bill and Adrian are faced with a choice of buying Nike or Adidas sneakers. They each have their brand preferences, but these preferences are weak compared to their desire to establish a group identity, and wearing the same brand of sneakers, no matter which it is, is a part of that identity. Adrian would, other things being equal, prefer Nike to Adidas, while Bill would prefer Adidas. Other things, however, are not equal, because if they choose different brands they lose a piece of their group identity.

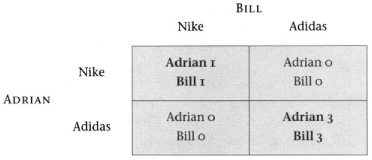

As genuine residents of Whimsley, Bill and Adrian weigh their choices numerically. If they both buy Nikes, Adrian gets 3 points, while Bill gets only 1. If they both buy Adidas, it is Bill who gets 3 points, while Adrian gets but 1. If they are both stubborn and buy different sneakers, they lose their group identity and so get no points whatsoever. This is the co-ordination game (see Figure 9).

FIGURE 9. Sneaker preferences at Whimsley Mall. The equilibria are in bold.

• If both buy Nike (top left corner), Adrian gets 3 points, and Bill gets 1 point. If Adrian changes his choice and buys Bill’s preference, Adidas, we are in the bottom left corner, in which both get no points, so changing his choice is not a good thing for Adrian. If Bill changes his choice to Adidas while Adrian buys Nike (top right corner), then again both would get no points. Bill may not be doing so well if both buy Nike, but he does even worse if the two of them buy different sneakers. Neither player can improve his outcome by a unilateral action, and so this outcome is an equilibrium for the game.

• If both buy Adidas (bottom right corner), Adrian gets a single point, while Bill gets 3 points. If Adrian changes his choice (top right corner), both get no points. If Bill changes his choice (bottom left corner), then again both get no points. Just as in the case of both buying Nike, neither player can improve his outcome by a unilateral action, and so this outcome is also an equilibrium for the game.

In one case Adrian gets his first choice, while in the other case it is Bill who gets his first choice. But in either case, it would pay neither player to switch, and this is the key to equilibrium. This game has not one, but two equilibria. One equilibrium is for both Adrian and Bill to buy Nike; the other is for both to buy Adidas.

Games with multiple equilibria exhibit co-ordination problems. The rules of the game require that the players make their choices independently and simultaneously. There is nothing in the game itself to help Bill and Adrian decide which choice to make. If Bill expects Adrian to insist on the Nikes, he should accommodate himself to that decision and choose Nikes also. If Adrian expects that Bill will insist on the Adidas, he should choose Adidas as well. On the other hand, if Adrian expects that Bill will be accommodating, he should choose Nike.

Let’s say that Bill and Adrian both buy Nike shoes, successfully co-ordinating their choices. While Bill is less happy than he wants to be, at least Adrian is happy, so that in one way this story has a better outcome than is possible in the prisoner’s dilemma. But in co-ordination problems in general, good choices are no guarantee of happy outcomes. Imagine if both Adrian and Bill preferred Adidas to Nike, but did not know the other’s preference (see Figure 10). The surprising thing is that “both buy Nike” is still an equilibrium, even though both of them would prefer to buy Adidas.

FIGURE 10. More sneaker preferences at Whimsley Mall. The equilibria are in bold.

Without communication, quite possibly they will end up in a bad equilibrium.

The role of externalities in the co-ordination game is even more pervasive than it is in the prisoner’s dilemma, altering not only how each player feels about the outcome, but also how each player ranks his or her choices. The prisoner’s dilemma demonstrates that choice and preference are separate concepts, and that we cannot make inferences about preferences by observing choices; the co-ordination game demonstrates that the nature of choice itself is complicated when choices are tightly coupled.

In situations in which co-ordination is paramount, the choice being made is not the one it seems to be. When pedestrians approach each other on the sidewalk, they are not choosing left or right, they are choosing to avoid each other. In the same way, Bill and Adrian are not choosing Nike over Adidas: instead they are choosing to buy the same shoe as the other one is buying. The particular shoe they end up buying is secondary to the problem. While the sales people at the shop may think that Bill and Adrian preferred Nike to Adidas, we know that they did not.

In situations driven by co-ordination problems, it becomes impossible to avoid the context in which the game is played: we are forced to go outside the formal structure of the game to find a mechanism for selecting among the various possible equilibria.

Thomas Schelling identified what he called the focal point effect.1 Anything that focuses the attention of the players on one equilibrium among many may lead the players to expect that others will make choices compatible with this equilibrium, and so successfully co-ordinate their actions. In one example, Schelling, providing no other information, asked a group of students where they would go if they were asked to meet another person in New York on a particular day. A majority of the participants chose a prominent meeting place (the information booth at Grand Central Station) at noon. That is, without communication, they managed to identify a focal point that enabled them to co-ordinate their actions.2 The goal of game theory is to describe, albeit in a formal and simplified way, real world situations. As game theorist Roger Myerson observes, Schelling appreciated that a “multiplicity of equilibria was not a technical problem to be avoided, but was a fact of life to be appreciated.”3 Myerson argues that Schilling’s focal point effect provides a foundation for the social role of concepts such as justice, tradition, and culture, and so constitutes “one of the great fundamental ideas of social philosophy.”

At first the focal point effect can seem like a cop-out. Having gone to great lengths to establish a mathematical theory of choice, we now throw up our hands and say “anything may tip the balance”: meaningless signals, conventions, traditions, or abstract ideas. And yet in the real world the idea is powerful. For example, social conventions often play the role of focal points: if there is a convention of passing on the left, then a pedestrian will not only choose to pass on the left but also expect others to adopt that convention and do the same: the convention becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, not because left is better than right, but because any convention is better than none.

If a mutual friend of Adrian and Bill’s has just bought Nike sneakers, both may deduce that the other is also more likely to buy Nike than Adidas, and so may choose Nike themselves (regardless of their own preferences) in anticipation that the other will choose Nike.

One of the dangers of using numbers to represent preferences, as the people of Whimsley do, is that they can introduce a perception of authority, objectivity, or precision. Such a perception is entirely unwarranted. I am using numbers here as a convenience so that we can talk about one choice being “better” than another, but that is all. What’s more, there is no need for these numbers to be objective, or indeed to have any meaning to anyone apart from the actor making the choice. We are discussing personal decisions, and Adrian’s and Bill’s ranking of preferences as they shop for sneakers is, as with Jack’s ideas about eating corn chips or Jill’s opinions on hiring a divorce lawyer, no one else’s business. There is no accounting for taste.

The numbers form what is called a utility scale. One of the ideas behind rational choice is that people make choices to achieve the best outcome they can, as measured on such a scale, or to “maximize their utility.” It is common for this “utility-maximizing” behaviour to be branded as automatically and simplistically selfish. For example, philosopher Mark Kingwell argues that the “notion of rational choice is the basic assumption of most contemporary economic theory.”

The individual person is reduced to the status of a consumer whose “rational” actions are a result of the presumed basic desire to be as happy as possible. That presumption – that every choice made by a person is what he or she thought rational at the time – is in turn the basis of what is known as rational-choice theory. Here, all decisions and actions decline to a base level of perfect rationality where people are always free of manipulation, coercion and necessity.4

In game theory, Kingwell argues:

The world is conceived of as an aggregation of individuals, lacking both class interests and political convictions, who function as utility-maximizing ciphers in a vast web of market relations. For them, “welfare” is defined hedonistically ... The individual person is reduced to the status of a consumer whose “rational” actions are a result of the presumed basic desire to be as happy as possible.

I am rational when I act efficiently to realize my goals, irrational when I do otherwise. My happiness or unhappiness, by extension, is just a function of how well or badly I am able to perform this series of choices, moving by stages from means to end. Rational choices are ones that contribute to my personal happiness, allowing me to get what I want and so “maximize my utility functions,” as the theorists say.5

But Kingwell oversimplifies the idea of “utility functions.” It is true that in our prisoner’s dilemma examples, the utility functions did not depend on other actors. As Jack and Jill evaluated their options in their divorce case, they did not adjust their points tally to reflect how they felt about the other person getting lots of money or no money. As Jill crossed the park, she did not worry if people would be angry at her: if she had, it might have changed the points she assigned. As The Journal and The Courier made their pricing decisions, they spared no thought for the fortunes of their competitor. In this sense, the actors involved were selfish.

In Bill and Adrian’s story we see something different. As Bill and Adrian assigned points, their assignments reflected a concern about the choice that the other would make. Adrian may be choosing to maximize his “utility function.” However, his utility is geared not to the possession of one or another brand of sneaker, but rather to a wish to identify and be identified with his friend Bill. The story expands the idea of a utility function to include a dependence on other people’s choices.

If we are to assess problems of status (my utility is increased if people see me as being of higher status than you), of “cool” (my utility is increased by the appreciation of my peers), of altruism (my utility is increased by seeing you happy), and of vengeance (my utility is increased by seeing you unhappy), we must necessarily build this new level of interdependence into our models. As long as we take this step, we can still use a game theory approach to guide our thinking about issues of choice.

Kingwell’s argument contains a nugget of truth in that it is indeed difficult to measure utility as seen in this way. Who, after all, can peer inside another’s heart? It is far easier to assume that utility corresponds to something easy to measure, like money, which is the route that much use of game theory in economics takes. In fact, as we’ve seen (chapter 6), corporations are almost required to act as if this is the case, so that when game theory is applied to their actions it makes sense to equate utility and money.

Kingwell is not the only critic who considers the rational choice effort to be misguided. Writer Linda McQuaig also disputes its usefulness: “The central character in economics is Homo Economicus, the human prototype, who is pretty much just a walking set of insatiable material desires. He uses his rational abilities to ensure the satisfaction of his material wants, which are the key to his motivation.”6

Again, there is a nugget of truth here: much economics discussion does tend to identify utility with “material desires.” But the concept of utility is also not quite that simple, as an increasing number of economists have recognized.

Multiple equilibria are the rule rather than the exception in game theory. Even simple games can have an infinite number of equilibria, and this oversupply of solutions is the source of some problems for the theory. In cases in which there is no obvious focal point outside the game that allows co-ordination, game theoretical problems can become intractable; theorists will have difficulty predicting the outcome of a particular situation.

Game theory has a mixed reputation within economics and political science because of this intractability. While many people in those fields recognize that it contains at its core a more realistic description of many situations than do models built on independent actions, others suggest that such a description is not of much use if it is too complex and intricate to make concrete predictions. The complexities of even as simple a place as Whimsley are such that prescriptions should be made very cautiously, and the real world is more complicated than Whimsley.

Economist and free-market enthusiast David Friedman offers a cautionary view of game theory and its applications:

Game theory is a fascinating maze. It is also, in my judgment, one that sensible people avoid when possible. There are too many ways to go, too many problems that have either no solution or an infinite number of them. Game theory is a great deal of fun, and it is often useful for thinking through the logic of strategic behavior, but as a way of actually doing economics it is a desperation measure, to be employed only when all easier alternatives fail.7

Constructing realistic economic models based on game theory has indeed turned out to be fiendishly difficult. As Friedman suggests, economists often find that in the real world of economic exchange there is not one story and one clear outcome – as they would argue there is in the classical competitive market with its many firms – but many stories and many possible outcomes. Along the same lines, Paul Krugman has made major contributions to the theory of international trade using game-theoretic ideas; and yet he writes that, when an industry is dominated by a few major players:

These players are bound to realize that they have some price-setting power. They are also likely to realize both that it is in their common interest to agree, at least tacitly, to set prices high, and that it is in their individual interest to cheat on that agreement and undercut their rivals. Is the eventual result a stable cartel, a perpetual price war, or an irregular alternation between the two? Hard to say.8

The difficulty of constructing realistic economic models of situations in which choices are tangled is a genuine problem, but it should not divert us (whether we are economists or not) from attempting to interpret the world that we live in, that we see around us every day. As Einstein famously said, theories should be as simple as possible, but no simpler. The absence of a single story as compelling as that of the competitive market should not stop us from recognizing the importance of externalities, and seeing how blinkered the MarketThink worldview is. Presenting the free market as “the way the world works,” as MarketThink popularizers do, with its corollaries of consumer power and corporate weakness, is misleading in the extreme when, as Jean Tirole writes in his textbook: “Most markets are served by a small number of firms with non-negligible market power,”9

Literary theorist Jonathan Culler talks about ways of making sense of the world:

Scientific explanation makes sense of things by placing them under laws – whenever a and b obtains, c will occur – but life is generally not like that. It follows not a scientific logic of cause and effect but the logic of story, where to understand is to conceive of how one thing leads to another, how something might have come about: how Maggie ended up selling software in Singapore, how George’s father came to give him a car.

We make sense of events through possible stories; philosophers of history... have even argued that the historical explanation follows not the logic of scientific explanation but the logic of story: to understand the French Revolution is to grasp a narrative showing how one event led to another.10

Game theory is another way of making sense of events in the world around us. For example, Bill and Adrian’s visit to the mall indicates that the choice people make might not be so obvious. According to the bottom lines of Nike and Adidas, Bill and Adrian went to the mall and chose to buy Nike, but we have seen that they really went there to express their joint identity through buying sneakers, and that choice depended on other factors and not just on brand. The criteria in their choices were mainly about each other’s preferences, and only secondarily about the sneakers themselves. The sneakers are a medium through which they express their identities, and pretty much any sneaker would do the job in a pinch.

What the story of Bill and Adrian suggests is that success can be a matter of simple luck. Bill and Adrian both walked out of Whimsley Mall with Nikes, but that says less about Nike shoes than it does about the almost random chance that led Bill and Adrian to settle on that equilibrium rather than on the Adidas equilibrium.

When the best choice is dictated by co-ordination, trusting individual choice proves to be a mistake. It leads to a winner-take-all world characterized by extreme inequality. While the winners in this world may reap a disproportionate share of the spoils, that overly large amount generally has little foundation in either merit or justice.