chapter eleven

IN AN IMPORTANT SERIES OF PAPERS, Rachel Kranton and George Akerlof (the latter of “market for lemons” fame) made one of the more successful efforts to apply game theory ideas to complex social questions – in particular setting out to broaden the “utility” that the players of their games maximize by incorporating into it the idea of “identity.”1 Taking the idea of identity from the disciplines of psychology and sociology, Akerlof and Kranton postulated that each of us carries around a self-image, in the form of an internalized set of prescriptions of how “a person like us” should behave under certain circumstances, and that our choices are ways of expressing who we are.

There is no need to posit a single source for this self-image: social conventions and expectations, internal psychological factors, genetic makeup – any and all of these produce our self-image. Whatever its source, if we violate the set of prescriptions that govern our identity, we experience an anxiety that game theory expresses as a cost: it reduces the utility that we would otherwise gain from the choice that produces this anxiety. Gender roles are an obvious example of how self-image can influence the choices that people make. A man who chooses an < option that society regards as feminine can experience a sense of anxiety, because it damages his image of his own “manliness.” Similarly a woman might experience anxiety if she acts in a way that society says “a good mother” should not act.

Such considerations start to take us away from the formulaic, one-dimensional characters of Whimsley and, more importantly, of standard economics textbooks. They bring us closer to the real world. What’s more, these ideas shine a new light on a whole set of real-world behaviours that have commonly been seen as “self-sabotaging choices” (property destruction in ghetto riots, for instance) or as genetic predisposition (women who abandon prestigious career paths), and show that these may be perfectly rational responses to social exclusion. But these responses do not lead to good outcomes.

The “ultimatum game” is one of those things that game theorists like to explore. So seemingly trivial it can hardly be called a game, it is even simpler than the prisoner’s dilemma. According to Martin Nowak, Karen Page, and Karl Sigmund, it goes like this: “Two players have to agree on how to split a sum of money. The proposer makes an offer. If the responder accepts, the deal goes ahead. If the responder rejects, neither player gets anything. In both cases, the game is over.”2

Many economists argue that the only rational action of the responder is to accept any offer given. Let’s say the players are asked to split $10, with offers allowed in increments of $1. As Sigmund, Ernst Fehr, and Nowak explain it:

The only rational option for a selfish responder is to accept any offer. Even $1 is better than nothing. A selfish proposer who is sure that the responder is also selfish will therefore make the smallest possible offer and keep the rest. This game-theory analysis, which assumes that people are selfish and rational, tells you that the proposer should offer the smallest possible share [$1] and the responder should accept it. But this is not how most people play the game.3

In real life – and the game has been tried out in many cultures in many places around the world – about half of the responders reject offers below 30 per cent, so that neither party gets any money at all. What is more, proposers often recognize this likelihood and make surprisingly generous offers, with the majority of them offering 40 to 50 per cent.

So what is happening here? Are humans being irrational in making such high offers and in refusing low offers? Or is our idea of rationality mixed up?

The answer lies in the utility function that most of us maximize. The assertion that “even $1 is better than nothing” insists that the monetary payoff in the game is the only outcome that individuals care about. But such an action is only “rational” (that is, utility-maximizing) if utility is the same as money. Once we accept that a player’s utility may include some aspect of self-image, we can see why rejecting a low offer can make personal sense. As Jon Elster points out, “People have material interests, but they also have a need to see themselves as not motivated exclusively by material interest.”4 Accepting a low offer would impose a cost on our self-image (am I the type of person who can be bought that cheaply?) that is just as real as the money being offered, and that at some point outweighs that offer.

One way of thinking about this problem is to imagine the construction of a game in two stages. The first stage is to construct what we might call a “bare” game, which is a game in which utility and money are the same thing and there is no account taken of identity or other interpersonal utilities. The second stage is to add the effects of identity to the mix to “dress” the outcomes and so produce the real-world version of the game being played.

We can see how this works in the case of the ultimatum game, which I further simplify here in order represent it more clearly. In this version, the players are given $10 to share, but the proposer has only two possibilities: offer an even split or offer the responder a token amount of only $1. The game is a little different to the other two-player games that we have seen so far in that it is sequential: instead of both players making their moves simultaneously, the proposer moves first, followed by the responder. We can still represent the game as a two-by-two matrix, but we must remember that the moves have to take place in order.

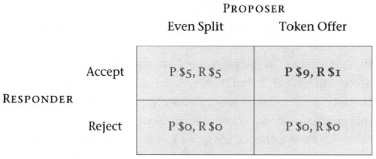

FIGURE 14. The bare ultimatum game, with only two proposals allowed. The proposer’s outcome is marked as P, the responder’s as R. The equilibrium outcome is marked in bold.

Figure 14 shows the possible outcomes for this case. If money and utility are the same, the responder would accept even the token proposal, and so the equilibrium is for the proposer to offer a single dollar to the responder. The proposer cannot improve this outcome by her or his own actions, and the responder cannot improve it either.

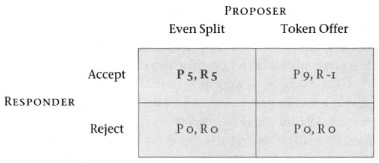

The second stage is to construct a “dressed” game, in which the responder sees the token offer as an affront (see Figure 15). To accept the token offer would damage the self-image of the responder, to the tune of, say, 2 units. Knowing that a token offer would be rejected so that neither player gets anything, the best option for the proposer is to offer an equitable split so that each gets $5 rather than nothing.

FIGURE 15. The dressed ultimatum game, with only two proposals allowed. The proposer’s outcome is marked as P, the responder’s as R. The equilibrium outcome is marked in bold.

All real-world games are “dressed.” The underlying private evaluations of costs and benefits are inevitably and unavoidably covered up by our own moral codes, the expectations of society, and personal likes and dislikes, among other things. The choices in this game are not irrational; they just have a richer utility function. The results are not unique to this game, of course, but apply across the board: research into how people really play these simplified games and why goes back to Anatol Rapoport, who carried out extensive studies of how people play the prisoner’s dilemma.5

Now let’s look at a slightly more elaborate case in which identity again plays a crucial role.

Jill is looking to move from her job in the backrooms of Whimsley Bank, an investment concern, onto the testosterone-charged floor of the trading room. She evaluates the costs and benefits of the move, and meanwhile her boss is also thinking about the possibility of moving Jill. We’ll see what both are thinking.

In listing the factors that Jill and her boss take into account when making their decisions, we will follow Kranton and Akerlof and go further in incorporating the effects of identity. They suggest that one player’s actions may influence not only that person’s own self-image but also the self-images of others around them. As a result there is a possibility that those other players may respond by rejecting the first player in order to restore their own identities.

For example, a woman undertaking something traditionally seen as a “man’s job” may challenge the self-images of the men holding that job: they may feel that the masculine qualities of their job, something that they feel proud of being able to do, are compromised if a woman can do the job just as well. They may respond by rejecting the woman in order to preserve their own self-identities. Someone from a lower social class who embarks on a prestigious career may influence the self-images of those left behind, who may in response accuse that person of having “ideas above their station.”

First, let’s listen to Jill as she considers her options.

• Money. I know there is more money to be made on the trading floor than there is here in my backroom job. That’s worth 2 points to me.

• Challenge. If I get a transfer, I expect the new job to be more challenging. That is worth something too: I’ll assign the new job an extra 2 points.

• Self-image. I do feel uncomfortable at the prospect of being immersed in the masculine world of the trading floor. I may have to act more “like a man,” and I may have to “squeeze the female part of [me] into a box, put on the lid, and tuck it away.”6 In short, there will be a cost to my feminine identity. I assign the new job a value of minus 3 for this damage to my self-image.

• Welcome. I am a bit worried about the welcome I’ll receive. Will I be seen as challenging the masculinity of the floor? If I act masculine, will I be seen by my new co-workers as pushy? And will they reject me in response?7 I assess this risk as worth a cost of minus 2.

If she takes the job, Jill will gain 4 points from the challenge and salary, but will lose 5 from the combination of her loss of self-image and her concern at the reception she will receive. So her best move is to stay put. She decides not to take the job.

Let’s look a little closer at Jill’s motives in avoiding the trading floor. First, she likes the idea of the job in a strict sense – she believes that she has what it takes to do it and that she would like doing it. But a job is not simply a collection of tasks. The conventional business world says that this job requires certain characteristics: aggression, competitiveness, decisiveness, risk-taking, even courage. In short, according to that world, it takes balls. There is a whole culture here that Jill is going to become a part of, and it is not a culture she is accustomed to. This is where the question of identity comes in. Everyone has a certain self-image, and along with that self-image comes a set of expected behaviours. If she were to move into this masculine world, Jill would run counter to those behaviours, and the idea of this makes her uncomfortable. She would risk losing her identity. The same may be true for a man taking a job as a nurse or kindergarten teacher, or for a woman becoming a firefighter. A lot of this is purely cultural, and not part of the job – it used to be that bank tellers and psychology professors were male, and things can change – but the costs associated with self-image are just as much a part of Jill’s decision as the salary is.

The second reason is a fear of rejection. This is Jill’s assessment of the likely reaction to her. By moving into this world and demonstrating that it can be done by a woman she would be challenging and threatening the self-image of the male traders. She realizes that they would feel a little less sure of the masculinity that their profession supposedly requires. There is a cost to the traders associated with Jill’s entry into their world. There is a chance that the cost to the existing traders of driving her out would be less than the cost to them of tolerating her and possibly feeling less manly.

Jill’s choice has consequences that go beyond her own career and has an impact on the prospects of other women. As a result of Jill’s choice the trading floor remains a predominantly masculine environment, a place that continues to be unappealing to other women who consider a move there. The arrangement with “all men on the trading floor” is an equilibrium from which we cannot escape through individual choice alone.

Now let’s look at the decision from the point of view of the bank. It is, after all, a commonplace MarketThink assertion that the market will force firms to eradicate hiring practices based on anything other than merit. Is there an incentive for the bank to put Jill on the trading floor? Jill’s male boss looks at things this way:

• Performance. I’m sure Jill could do the job well. That is, she could carry out the tasks associated with the job: she has the motivation, the skills, and the experience to do the job. I’ll assign her anticipated good performance a value of 3 points compared to her nearest competitor (who is male).

• Team Performance. As a responsible manager, I am worried about the atmosphere on the team if Jill joins. I’m concerned that her presence would disrupt the good-natured, if sometimes coarse, camaraderie that does so much to encourage hard work on the part of the team members. If Jill’s presence does disrupt the atmosphere, it may make a difference of minus 1 point per team member, and there are currently ten people on the team.

• Rejection. The team may recover their spirit by rejecting Jill. The cost of such actions would be 5 points, spread across the team. In addition, if the team does take such action, they will detract from Jill’s performance, to the tune of 4 points.

Looking at these possibilities, the manager decides that whether or not the team acts against her, adding Jill to the trading floor will not improve the performance of the team. And if they do act against her, things will be worse still. Purely in the interests of the bank, he decides to hire her nearest competitor instead. Given the environment, even if the best candidate is female any bank that moves women onto the trading floor will suffer in comparison to its competitors.

So whether Jill makes the decision or her boss makes the decision, the equilibrium outcome at Whimsley Bank is for the trading floor to be all-male. Being the equilibrium does not mean it is a good outcome, though. It may be that it is one of several possible equilibria, some of which could have better outcomes. For example, an all-women trading floor could be another equilibrium: if the trading floor were full of women, Jill would suffer neither the loss of identity nor the fear of rejection, and she would decide to move. Meanwhile, men may fear that it would be unmanly to take a trading-floor job if all the traders there are women. And if the tipping point for acceptability is less than 50 per cent of the population, then there will be equilibria, as there are in many professions, consisting of a mix of both genders: in which there are sufficient from both sexes to make the profession welcoming for both male and female newcomers. But, of course, moving from one equilibrium to another requires a change sufficient to reach the tipping point of a self-sustaining population of women: it requires a co-ordinated and collective action. The existing equilibrium is a fine outcome for the existing male traders, at the cost of the self-excluding female potential traders.

The role of sexism here is subtle. All the external world sees is that Jill does not apply for the job and there are, after all, several possible reasons for this decision. Perhaps she knows she “doesn’t have what it takes.” Perhaps she isn’t qualified. Perhaps she values her home life too much. But we have the privilege of knowing her thought processes and as a result we know that, even though she could do the job, even though she knows she could do the job, even though she wants the pay and status that would come with the job, she is excluding herself from it and remaining in her relative ghetto. There is no need for the bank to discriminate and no need for the men of the trading floor to do anything other than demonstrate their masculine solidarity in order to frighten off intruders. Jill’s self-exclusion is not a bad choice: we have seen that it is the best choice available to her in the circumstances, and that she makes it for good reasons. But the end result of the good individual choices of the women at her bank is a bad set of outcomes for each and every one of them: the persistence of segregation and exclusion.

Identity, in one form or another, is a strong motivational factor in many decisions. Taking account of identity helps us to move beyond the simplistic association of utility and money. It is, for example, simply not true that money is the only, or even perhaps the major, motivator of workplace performance. One strong motivator is that some people identify themselves as skilled professionals. They work hard and carefully because producing a good product bolsters their self-image. As we have seen, identity can also hold people back in their progress at work.

Identity plays a role in other contexts also. One that Akerlof and Kranton explore is that of apparently self-destructive behaviour such as vandalism in poor and socially excluded communities.8 Members of such a community can take one of two attitudes to the dominant culture: they can adopt it (despite not being a part of it) or oppose it.

Those who adopt the dominant culture face the same dilemmas that Jill faced: dominant groups often identify themselves by exclusionary criteria, and the pursuit of a career that is traditionally associated with the dominant group comes at a cost of compromising or losing one’s original identity. What’s more, the dominant group may respond by excluding those from outside who attempt to adopt their culture, and those in the excluded community who oppose the dominant culture may make life difficult for those who adopt it.

Those who oppose the dominant culture are also faced with a dilemma. The prescriptions for the oppositional identity may involve antisocial or criminal activity that maintains their oppositional identity only at an economic cost to themselves and those around them.

Such a picture leads to several possible equilibria. One is for all members of the excluded community to adopt the dominant culture. Another is for all members of the community to oppose the dominant culture. A third is a mixed equilibrium that includes some of each identity.

The “all adopt” equilibrium may appear to be the “best” outcome, but it is viable only when the dominant group does not reject the excluded group. If the cost of adopting the dominant culture brings with it a loss of identity and a continued exclusion from that culture, the individually “best choice” may be to instead oppose the culture. The option to adopt the dominant culture is most likely to be pursued when there are significant career opportunities for large numbers of people from the excluded group.

If adopting the identity of the dominant culture and choosing its associated prescriptions yield few such opportunities for advancement, the equilibrium outcome is one in which some or all of the excluded community reject the dominant culture and adopt an identity that has different sources of validation.

For example, Akerlof and Kranton describe disruption by Mexican-American male students in a West Texas high school, quoting the only such student whose family had made it into the middle class: “We were really angry about the way the teachers treated us. They looked down on us and never really tried to help us. A lot of us were real smart kids, but we never figured that the school was going to do anything for us.”9

In that kind of environment an individual Mexican-American student has two choices: to adopt the school-promoted identity and follow its prescriptions – working hard, being obedient, and so on – or to reject it. If individual students figure that the school is not going to do anything for them, then adopting the prescribed identity gains them nothing and they risk being seen as a traitor by others who reject the school. But adopting the oppositional culture and following its prescriptions – provoking fights with students of other schools at away football games, breaking rules regarding alcohol, illegal drugs, and smoking – can provide them with a sense of integrity, and at the same time they avoid the cost of rejection by peers.

The choice is not, though, simply a matter of peer pressure. While the reaction of other Mexican-American students is part of the picture, it is only one part. Other factors in the choice are the reaction of the school authorities and the internal sense of self, dictated in part by the existing school dynamic. Choosing what seems to the outside world to be self-destructive behaviour becomes a rational response to a high degree of exclusion.

This book is based on the idea that a good or “rational” choice is one that provides the most of something that is called “utility,” but throughout it has specified that “utility” in different ways. This is deliberate, because utility means different things to different people. For some, the thrill of a fast roller-coaster ride is a significant source of utility, for others it is simply a source of nausea. For some, thrash metal music is electrifying, for others it is as much fun to listen to as fingernails on a blackboard at high volume. There is nothing right or wrong about these preferences; they are simply a matter of different tastes. The idea of “rational choice” has nothing to say about the formation of preferences. It just says that we choose what gives us the most utility.

The utility-maximizing Homo Economicus has been widely criticized as a simplistic picture of human motivations. In response, game theorists justify their apparently cynical assumptions about the selfishness of so-called “rational” behaviour by arguing that the utility may include sympathy for other players (so the utility of player A may be increased by a high score for player B) or spite (the utility of player A is increased by a low score for player B), as long as these utilities are all worked into the scores for the game ahead of time. The difficulty of measuring these internal motivations is too often used as a rationale for ignoring them, so that in too many MarketThink stories the idea of utility is identified with purely private costs and benefits, or more simply still with money. But as the idea of utility becomes based on more realistic scenarios, and as our choices are recognized to be more complex than choosing between apple juice or orange juice, so too do externalities become more and more important, and the dynamics of our individual choices become more tangled.

The notion of utility, then, becomes increasingly complex as we move through the examples in this book. In the story of their divorce, Jack’s and Jill’s concerns were limited to monetary outcomes. When Jill was deciding whether to drop her paper cup or not she did worry about non-monetary gains and costs, but her utility function was a purely private one: the actions of others affected her only through the number of coffee cups she had to see as she walked through the park. When Jack was deciding whether or not to buy a new car, his concern was broader, and included not only the qualities of the car he was to buy, but also his social status – with the way in which he was viewed by others in his neighbourhood.

The co-ordination game is built on a utility function that is sensitive to other people’s actions. Many of our consumer choices were seen to be governed by notions of what is fashionable or cool, notions that depend on how people view each other and how we respond to the gaze of others. The inclusion of complex psychological and sociological ideas such as identity into the “rational choice” model leads to even more complicated and intricately tangled dynamics, in which “individual choice” is an unreliable and treacherous guide in our pursuit of prosperity and happiness.

We can draw a few simple lessons from all of this messy real-life complexity.

INDIVIDUAL CHOICE DOES NOT GIVE US WHAT WE WANT. Some critics argue that the market in its purest form leads to bad results, and so people must be making bad choices. Others maintain that people with free choice will make good choices, and thus individual choice will make us happy. But there is a third option: people make good choices, but end up badly off anyway.

A lot of people shop at Wal-Mart, but – whatever MarketThink would have us believe – these shopping trips are not votes in favour of a Wal-Mart-shaped city. They do not demonstrate that we are happy in a Wal-Mart-driven world, and it is quite possible that we would prefer to have a city with smaller and more central stores. We need the chance to pursue those visions too.

MarketThink asserts that regulations for national media content or urban planning demonstrate a lack of trust in the public to make its own choices: that people left to themselves are incompetent. It maintains that individual choice is all we need to get us where we want to go. Critics of MarketThink too often accept this assertion, and point out the obstacles that prevent people from making good decisions, notably the flood of advertising in which we are all immersed. But most people do make reasonable choices most of the time. It’s just that good choices are not enough.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE PROMOTES THE PRIVATE, DEGRADES THE PUBLIC. There are predictable ways in which individual choice fails to give us what we want. The temptation to free-ride means that anything public or shared, such as an unpolluted environment or a compact city, is vulnerable in a world of individual choice, even if everyone values these things highly.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE PRODUCES INEQUALITY BASED NOT ON MERIT BUT ON LUCK. When the choice is between joining the herd and being trampled by it, we end up in a winner-take-all society, with most of us losers. The winners have much in common with lottery winners, and their rewards are out of proportion to the benefits they have brought to society.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE DOES NOT PRECLUDE THE EXERCISE OF POWER. When value-cloaked ideas such as the “right to work” are used to provide a cover for attacks on trade unions, political power is being exercised. People opposed to those attacks need to be able to assert that collective action and collective choice are legitimate values too. When homogeneous and predictable products from global companies drive out local vendors, economic power is being exercised. Consumers need to recognize that we are not getting what we want, and that instead we are ending up with less choice as asymmetric information takes hold and local networks of expertise unravel. We need the right to act together.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE DOES NOT PRECLUDE EXPLOITATION. The idea of free exchange is at the root of MarketThink ethics – who enters a free exchange if it does not make them better off? – but free exchange in itself is far from problem-free. Can there be, for instance, such a thing as free exchange between unequal parties? In that kind of an exchange the stronger party can afford to walk away from the transaction if they decide it is not to their benefit. The end result is that the lion’s share of the gains go to those who can afford to walk away.

PREDICTABILITY DRIVES OUT QUALITY. Good-quality offerings at the right price will not always find buyers. When one side lacks certainty about the quality of the goods being offered, exchange becomes fraught with uncertainty and many potentially beneficial exchanges fail to take place.

In an advertising-driven world, the franchise model drives out the independent vendor, regardless of quality. In a socially segregated world, the alternative to affirmative action is not hiring by merit, because the market for lemons tells us that insiders will always have a built-in advantage over outsiders, regardless of quality.

SOCIAL EXCLUSION IS SELF-SUSTAINING. The preservation of identity is a powerful force shaping the choices that we make. Our identities and self-images come with a set of prescribed actions that support and maintain exclusions and disadvantages. Members of excluded groups face a no-win choice: abandon the pursuit of the benefits that are enjoyed by the dominant group, or continue that pursuit at the cost not only of losing their identities but also of being rejected by both their own communities and the dominant group.

The ideas of MarketThink clearly work within a limited domain. They do provide insight into some areas of our lives in which only private costs and benefits matter and there are no side effects to our choices, in which we are impervious to the choices made by others. They are limited to choosing between similar commodities in a world in which quality can be appraised at sight (no lemons here), and increasing returns and network effects are negligible.

To sell this picture of choice as “the way the whole world works,” as MarketThink does, is overreaching on an epic scale. To appreciate the richness of the world around us is to appreciate that externalities and the tangles they produce are pervasive: that (to go back to chapter 2), society is more like a liquid than a gas.

It is time to place collective action back on the table. Of course collective action does have its difficulties, but the ideals of collective action have no more been destroyed by, for instance, the failure of communism, than the ideals of individual choice were destroyed by the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Most of all, it is time to embrace complexity. This book is about a worldview; it does not pretend (as MarketThink does) that a single solution exists to solve all our problems. Jane Jacobs got it right 45 years ago when she wrote of the problems of cities:

City processes in real life are too complex to be routine, too particularized for application as abstractions. They are always made up of interactions among unique combinations of particulars, and there is no substitute for knowing the particulars ...

Being human is itself difficult, and therefore all kind of settlements (except dream cities) have problems. Big cities have difficulties in abundance, because they have people in abundance. But vital cities are not helpless to combat even the most difficult of problems.10

Societies, like cities, have difficulties in abundance. It is a prerequisite for successfully overcoming these difficulties that we recognize the complexity of the world we live in. Doing so demands that we reject the worldview and prescriptions of MarketThink and recognize that the “right to individual choice” is a fool’s gold. A reliance on individual choice will lead us not to broadly based prosperity, but instead to ever-increasing inequality and the loss of those things that we hold in common.