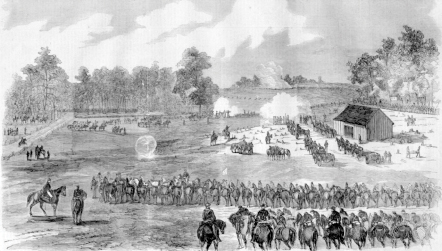

Alfred Waud made a sketch of the opening of the battle of Hanover Court House that appeared in Harper’s Weekly on June 21, 1862. Branch’s brigade, particularly the 18th North Carolina, can be seen on the hill in the background. Harper’s Weekly

“Boys, you have stern work before you.”

After the disastrous battle of Manassas in July 1861, Federal forces retreated into Washington’s defenses. Abraham Lincoln, seeking a new army commander, selected Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who strengthened the capital’s defenses while building a 100,000-man command he christened the Army of the Potomac.

The new commander was charged with two tasks: protecting Washington and crushing the rebellion while capturing the Confederate capital at Richmond. At first, he wanted to take his army along the same route used in July 1861, an attempt to outflank the Confederates dug in around Manassas. Lincoln favored this plan. It kept the Federal army between the Confederates and Washington. However, McClellan, citing strong Confederate defenses and exposure of his own flanks and supply lines, came up with his own plan. McClellan wanted to sail down the Chesapeake Bay, disembark at Urbanna on one of the peninsulas east of Richmond, and quickly move against the city before the Confederates could respond. Lincoln eventually acquiesced, providing McClellan left enough men to protect the Federal capital.

Alfred Waud made a sketch of the opening of the battle of Hanover Court House that appeared in Harper’s Weekly on June 21, 1862. Branch’s brigade, particularly the 18th North Carolina, can be seen on the hill in the background. Harper’s Weekly

Since Manassas in July 1861, Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston had labored to fortify their position. Johnston, a 55-year-old West Point graduate, commanded the Confederate forces in northern Virginia along a 50-mile front from Dumfries in the east to Leesburg. However, he could only muster 36,207 officers and men to cover this area. So in late February, he chose to abandon northern Virginia, consolidating his forces behind the Rappahannock River. With the Confederates around Fredericksburg too close to Urbanna, McClellan was forced to adapt, landing instead at Fort Monroe on a different peninsula east of Richmond. Lincoln once again approved the plan, only asking that “adequate” forces be left behind to defend Washington. On March 17, the lead elements of the Army of the Potomac got underway. Confederate forces scrambled as McClellan’s soldiers landed on the peninsula and began moving inland. Yet the Confederate bluff had been so convincing McClellan believed he faced superior numbers and called for a siege of the city of Yorktown. It took weeks for McClellan’s soldiers to dig embrasures and haul heavy cannon to the line. All the while, Johnston was transferring his army from the Fredericksburg area to Yorktown to oppose the Federals.1

While Federal soldiers labored in the swamps southeast of Richmond, Confederate authorities began transferring troops from other states to stymie McClellan’s advance. Seven brigades containing 30 infantry regiments, two infantry battalions, and three artillery batteries were sent to Virginia in the space of just a few weeks.2

Orders arrived in early May 1862 for the transfer of Branch’s brigade. Robert E. Lee wrote Branch’s superior of the necessity to concentrate forces. Each regiment was issued three days’ rations for the move. The regiments boarded a train in Kinston, which took them to Goldsboro, where they boarded the Weldon Railroad and made their way north. They moved in this order: 37th Regiment, 903 officers and men; Latham’s Battery, 80 horses and 99 men; 33rd Regiment, 644 officers and men; 28th Regiment, 1,217 officers and men; Brem’s Battery, 51 horses and 97 men; 18th Regiment, 816 officers and men; 7th Regiment, 876 officers and men, and Bunting’s Battery, 70 horses and 91 men. The brigade’s sick were to be transported to a general hospital, and the number of available surgeons increased.3

It took time to gather enough rail transportation. The 28th NC departed on May 2, The 7th NC left on May 4 and arrived in Richmond on the evening of May 6 after a “very disagreeable” trip, according to John Johnston, “in open flat cars.” William McLaurin wrote that his regiment, the 18th, departed on May 7 and arrived in Richmond the next day. The trip proved fatal for some men and dangerous for others. According to Bennett Smith, Hugh Icehower of the 37th, “was a drinking he had un cupled the cars 3 times and them a running he was on top of the train and would cimbe down between them and pull the cupling pin out and on the 4th time he fell between and the wheels cut him in 3 pieces.” Near the Virginia-North Carolina line, the train carrying the 37th Regiment derailed, injuring several men who were transported to a field hospital in Petersburg.4

Richmond was the largest city most brigade members had ever seen. Since becoming the Confederate capital in May 1861, its original population of almost 40,000 more than doubled. Richmond was a center of the war industry as well: scores of businesses, both private and government, produced necessary munitions and accouterments of war. Marching between railroad stations to swap trains was about the only experience the Tar Heels had in Richmond proper, unless ill or wounded in battle, when they required treatment in one of the numerous hospitals that sprang up in the city during the war. Richmond “is a big place” wrote one brigade member. “I saw the Statute of Washington he was sitting on a horse Jest like [a] man drest in military clothes … ; the nigurs was drest finer than the white people.” The 37th NC’s chaplain, Albert Stough, recalled the cheering ladies “waiving white handkerchiefs from every cottage. … Southern flags waving [and] … many bouquets thrown to our boys as we passed by.”5

As the 28th Regiment passed through Richmond, Col. Lane visited Gen. Robert E. Lee personally to request better weapons for his command. The general promised to send rifles to Gordonsville, and then, following up on current matters, inquired about Lane’s flank companies. On May 10, Lane had written Branch about trying to get at least 130 rifles for his command. Branch responded that “400 Enfield Rifles” had been ordered for the flank companies of the 28th and 37th Regiments.6

Strategically important Gordonsville sat at the intersection of the Virginia Central RR, running from Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley, and the Orange & Alexander RR, which ran north, all the way to the outskirts of Washington, D. C. The connection to the Shenandoah Valley was crucial, a lifeline funneling both soldiers and supplies from the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy” to the Eastern theater of war. Branch’s brigade was placed under the command of Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell, whose division was located in the Shenandoah Valley. Confederate forces spread out in a huge front across central Virginia. Joe Johnston, with the principal Confederate army of 60,000 men, confronted McClellan’s 100,000-man host east of Richmond,. At Fredericksburg, Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. Charles Field with 2,500 soldiers, faced a Federal force of 30,000 men. There were an additional 6,500 Federals in the upper Rappahannock River area. Ewell and Jackson, with 8,000 men in the Shenandoah Valley, watched 20,000 Federals. Beyond the Shenandoah Valley were an additional 20,000 Federal soldiers. General Lee, on assigning Branch to Ewell’s division, wrote that Branch was to remain east of the Blue Ridge, not to be called upon unless absolutely necessary.7

On May 10, Branch’s movement toward Madison Court House was interrupted by a note arriving from Ewell that the Federals were breaking camp, possibly heading toward Fredericksburg. Branch was ordered to Orange Court House. Word then arrived the Federals had merely changed camps. On May 14, Ewell directed Branch to take the troops in and around Gordonsville “into the valley… to Lurary.” Ewell believed Branch’s men should have at least five days’ rations, but needed to travel light. “The road to glory cannot be followed with much baggage,” explained Ewell.8

Branch’s men set out on the evening on May 16 in torrential rain and managed to cover 12 miles before orders came from Ewell to halt. At noon on May 17, Ewell told Branch to continue, but after covering three miles, he was again ordered to halt and return to Gordonsville. The next day, Ewell ordered Branch simply to remain where he was. This constant stream of conflicting instructions frustrated everyone. Branch believed it originated “from rivalry between Gens. Jackson and Ewell,” and declared it “very unfortunate” that so many junior officers “of the old army” had been transformed “into Brigadiers and Major Generals.” Sergeant John Alexander (37th NC) confided to his wife that he had never been “so completely worn out in my life as when we halted Saturday night. … you know that I was always opposed to walking.” Colonel James Lane told a fellow former Confederate officer after the war that Ewell’s order

to the Valley, as was publically understood, to join Ewell; but really, as it afterward turned out, to deceive the enemy & make him believe that reinforcements were being sent to Jackson. After passing through a little town or village called Criglersville, not far from the eastern base of the Blue Ridge, we were kept moving slowly forward during the day in full view of a Yankee signal station & at night we were marched back & ordered into bivouac … None of us went over the mountain.9

George Johnston (28th NC) recalled the brigade received orders on the afternoon of May 19 to proceed toward Ewell and Jackson. “In high spirits, with many a shout and song, we pressed manfully on.” They marched into early evening before stopping, and watched a thunderstorm break upon the mountaintop. Up early the next morning, the brigade began to ascend the mountain, enjoying the scenery as they climbed. After three miles, Johnston’s regiment was resting by the roadside, when a “courier came dashing through our ranks” with urgent orders from General Johnston himself sending Branch’s brigade to Hanover Court House. At Madison Court House, Branch informed Ewell about the new orders, and even while marching in the opposite direction, told Ewell he hoped to “soon have the opportunity to report to you in person.” Branch obviously wanted to join in the action in the Valley and possibly restore what reputation he had lost at New Bern.10

Down the mountain went the brigade, covering the first eight miles in three hours. From the end of the column George Johnston witnessed “poor fellows … dropping out by scores, and lining the road-side with their woebegone faces.” Johnston recalled leaving a fellow officer in the 28th who had completely given up “stretched on his back in a thicket.” The brigade covered 22 miles before going into camp. The next day, they arrived in Gordonsville and began to transfer via rail to Hanover Court House, arriving on May 22.11

Like Gordonsville, Hanover had an important railroad junction. The Virginia Central ran through Hanover County and intersected with the Richmond, Fredericksburg, & Potomac RR at Hanover Junction. It was a crucial line for men and supplies coming to Richmond. Branch’s redeployment from the Gordonsville area to Hanover placed him between two large Federal forces. General Johnston ordered Branch both to protect the railroads, and, if a battle commenced, to attack the enemy’s flank.12

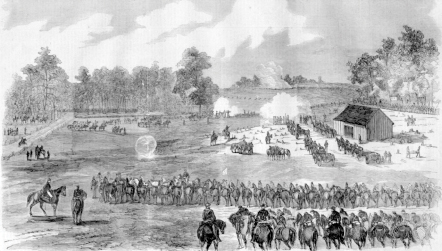

This First National flag, made of silk and presented to the 33rd North Carolina in September 1861, was the banner the regiment most likely carried during the battle of Hanover Court House. North Carolina Museum of History

When McClellan personally left Washington, D.C., he forwarded a memo to the war department outlining the 74,000-plus soldiers he left behind to protect the capital. However, upon recalculation by Federal officials, it appeared McClellan had left a scant 26,761 men, too few for Lincoln’s definition of “adequate” defenders. The president ordered Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s I Corps to remain behind. and over time, augmented McDowell’s force with additional troops, including some from the Shenandoah Valley. About the time Branch arrived at Hanover Court House, McDowell’s force numbered around 40,000 men. These men were posted just north of him, at Fredericksburg, while southeast sat McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. McClellan, always believing he was outnumbered, repeatedly requested McDowell’s men. Lincoln eventually conceded, but required McDowell to stay between Washington and the Confederate army. McClellan thus had to extend his right flank to link up with McDowell’s men. This required eliminating the Confederates in Hanover County.

The arrival of Branch’s brigade did not escape notice. A party of Pennsylvania cavalry reported on May 24 a Confederate force composed of “not less than 3,000 infantry, six pieces of cannon, and 300 cavalry, four regiments having arrived day before yesterday.” Confederate pickets spotted the Federal soldiers who were as close as Taliaferro’s Mill, reconnoitering the Confederate position. George Johnston recalled being at Colonel Lane’s tent on May 24 when the drummers beat the “Long Roll.” Soldiers scrambled into ranks, marched to a large field, and formed a line of battle where they stood “in a drenching rain,” before being allowed to return to camp. The enemy had been only 30 Federal cavalrymen instead of an entire regiment as originally reported. The next day the brigade repeated the drill, marching two miles to meet an illusory enemy force. Branch ordered his regimental commanders to ship some 309 sick men and the excess baggage via rail to Richmond, while he abandoned camp near Hanover Court House and moved toward Ashland. On the evening of May 26, Branch established his headquarters at Slash Church. His command now contained not only his five regiments, but Latham’s Battery of four guns, the 12th NC, the 45th GA, and an undisclosed number of Virginia cavalry.13

Cavalry pickets were positioned at the intersection of local roads. Around midnight, two companies of the 37th were dispatched toward Taliaferro’s Mill to reinforce the Confederate pickets. Branch bedded down at the church for the evening, sleeping in his clothes in one of the pews. He was joined by his staff, as well as by Lt. Col. Edward Haywood (7th NC) who was suffering from a toothache. An increasingly active Federal presence undoubtedly worried Branch. He hoped for the arrival of Brig. Gen. Richard Anderson he had told his wife earlier. “He ranks me and I would rather be relived of the responsibility of chief command.”14

Stonewall Jackson’s activities in the Shenandoah Valley postponed the planned conjunction of McDowell and McClellan, with some of the troops sent from the Shenandoah Valley ordered to return and try to trap Jackson’s force.

The others were ordered to remain in place near Fredericksburg. McClellan still believed that at some point McDowell would join him and decided to clear the Confederates between his force and McDowell. He assigned the task to Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter and the V Corps. Porter’s men set out early on the morning of May 27, but the incessant rains turned the roads into quagmires, slowing the march to a crawl. The Confederates fared little better. One officer in the 28th NC complained that “all suffered much that night as we had no tents neither had we slept in tents one night in five weeks, traveling all the time in the mud & rain.” Porter divided his force into two columns. The first was composed of a division of infantry, with artillery and cavalry support. This force advanced northwards along the New Bridge Road. A single brigade of infantry, with cavalry, composed the second column, and it advanced along a road running next to the Pamunkey River. Porter assumed that Branch’s small force was still near Hanover Court House, and this second column was ordered to strike Branch’s flank and rear.15

As the Federals struggled through the mud, they encountered Confederate cavalry at every intersection. At times, the Federals had to deploy infantry and artillery to assist the cavalry. Branch received reports of a small body of Federals moving toward the picket post belonging to the two companies the 37th NC sent out the previous evening. He ordered Lane to take the entire 28th Regiment, along with a section of Latham’s battery, to reinforce the pickets. At the same time, he sent the 45th GA down the Ashcake Road toward Ashland to repair the railroad and to keep open the Confederate line of retreat. Lane led the 28th past the rest of the brigade, across the railroad tracks, and to the farmhouse of Dr. Kinney. Ten men from each company were detailed to fill their companies’ canteens at a nearby well. From the Kinney farm, Lane marched his regiment down toward the Pamunkey River. However, when he reached the picket post, he found it abandoned. Lane searched for the pickets until a courier informed him of Federals troops advancing in his rear. Then he quickly turned his column back toward the Kinney farm.16

Captain George Johnston and Company A were now in the lead. “I had the privilege of heading the noble column,” he recalled in his diary,

marching by the side of our gallant Col. Every moment we expected to fall upon them. I was as cool and collected as ever in my life, and, though busily engaged in cheering up my men, thought often of my beloved Nannie wife, and asked God to cover my head in the hour of battle, for her precious sake. … We were looking for the foe upon our right; a thick wood lay in that direction; in this the Col. feared an ambush, and ordered me to deploy my 1st platoon as skirmishers through it, to look out for the enemy, and to hold them in check until he could form the regiment. I obeyed and soon had my men beautifully deployed for nearly quarter of a mile to the right of the head of the column. Half of my 2nd platoon was deployed in like manner upon the left, under command of 2nd Sergt. Martin. … At every step we knew not but that the next would throw us in their midst—but my brave boys pressed on unfalteringly. … Suddenly I heard the report of several rifles; I listened and in the distance heard the clear voice of Col Lane, ‘Halt, Front-By Co. left wheel, march.’17

Lane had stumbled upon Federal skirmishers from the 25th New York Infantry. After properly aligning his Tar Heels on the road to his front, Lane bellowed, “Charge—charge them, brave boys!” The 28th Regiment, some 900-men strong, crashed through the woods, through a ditch, and over a fence, chasing the New Yorkers on the east side of the New Bridge Road to the south. Lane led the 28th into the yard of the Kinney House, and the fighting quickly turned into a hand-to-hand struggle with the Federals on the west side of the road, often with bayonets, swords, and knives. A New Yorker reported one of his officers lay dead near the house, “and all through the yard and around the house the dead of both sides covered the ground.” What was left of the four Federal companies on the west side of the road quickly retreated. During the attack, the reserve of the 25th New York tried to advance toward the fighting, but portions of the 28th redeployed and opened fire, driving them back.18

Lane quickly re-formed his men to confront other enemy troops forming to his south. Lane ordered his men to drop their rain-soaked knapsacks and to lie down behind a fence. He then deployed the two guns of Latham’s battery, while sending word to Branch that he needed reinforcements. Prisoners the 28th captured were passed on to a detachment of the 4th VA Cavalry, while with the infantry coming up in support, the artillery pulled back behind the Kinney farmhouse structures. William Speer recalled the deadly Federal artillery fire. While the regiment redeployed, “a shell passed so near my head I dodged to one side & came near to falling, the shell striking the flagbearer & a private in Company C.” In another instance, he saw “a shell strike a young Mr. Roberts of Co. A injuring him badly fracturing both of his thighs from which he died. Also I seen two more men of Co. A killed with shells, taking the top of one of their heads & cutting the other” in two. At the advance of a Federal brigade, despite Lane’s attempts at extending his flank and redeploying his men, he couldn’t withstand the onslaught until reinforcements arrived. In their hasty withdrawal, the Confederates had to leave their dead, seriously wounded, knapsacks, an ambulance, wagon, and one of the artillery pieces. The bulk of the regiment headed back toward Hanover Court House, with the Federals in pursuit. The remaining Confederate artillery piece stopped at least once and opened fire at the pursuers. Under the impression they had finally found the main Confederate line, the Federals deployed their infantry and artillery; all the while the Confederate infantry continued to retreat beyond the court house.19

Lane’s requests for reinforcements had not gone ignored. Unbeknownst to Lane, Branch was contending with a fight of his own. As enemy forces pursued Lane, two other Federal regiments and a section of artillery headed down the Ashcake Road, intent upon cutting the telegraph and wrecking the railroad. A Confederate cavalry picket spotted and reported the advance. Colonel Lee of the 37th NC ordered Lt. Col. William Barber to deploy two companies into the woods beyond Lebanon Church while Lee rode to Slash Church to report this movement. Barber withdrew his two companies, falling back and reforming on the rest of the regiment. Latham’s other section of artillery arrived and soon commenced returning fire. Lee realized upon returning that the enemy force was much larger than his own and called for the 12th NC to come to his aid.

Federal artillery fire soon found the range on the Confederate guns and destroyed one caisson, whereupon Latham redeployed his artillery. The Federal brigade commander, Brig. Gen. John Martindale, requested Porter send reinforcements. Porter’s answer flabbergasted him: he was ordered to send one regiment up the railroad tracks to destroy bridges and structures, while the other regiment and artillery moved off to the right toward Hanover Court House. Martindale dashed off another note, reiterating a large body of Confederates to his front and left, not his right. But he obeyed his orders and broke off the engagement. Mud and a broken caisson caused a delay, and Martindale used his remaining regiment, the 2nd Maine Infantry, as a rear guard. Porter’s second reply again informed Martindale there were no Confederates in his front. Disgusted, Martindale sent a third courier to Porter, while gaining permission from his division commander to assume responsibility for his own actions. A Federal cavalry picket soon reported that the Confederates were advancing, and Martindale ordered the 2nd ME back to the intersection of the New Bridge and Ashcake Roads.20

About the time the long-range artillery duel ceased, Branch arrived on the field from his Slash Church headquarters. Lane’s request came shortly thereafter, and Branch chose to send the 18th, 33rd, and 37th regiments to the 28th’s assistance, but discovered the road blocked. As Martindale was posting the 2nd Maine, he spied the 44th NY Infantry, with a section of Martin’s Massachusetts Battery in tow. When Martindale explained his plight, the commanders of the infantry and artillery agreed to place themselves under his command. Martindale also sent for the fought-out 25th New York. He positioned his men with the 2nd Maine on his right, masked by a thick timber, then two artillery pieces, the 25th and 44th NY on his left. Meanwhile Branch quickly developed a plan of attack. He ordered the 33rd NC toward the Federal left and the 37th to attack the Federal right, both regiments through the woods. The 18th NC would move across an open field and attack the center. The 12th NC was held in support.

From the start, Branch’s plan fell apart. The 33rd entered the woods on the right and promptly got confused. Companies A and B were deployed as skirmishers, and as they advanced, a courier arrived, directing the regiment to fall back. However, regimental commander Lt. Col. Robert Hoke couldn’t recall his skirmishers who continued to advance toward the New Bridge Road. At the edge of the woods, they discovered a small group of Federal soldiers in a clearing. Captain Joseph Saunders wanted to capture them and ordered a detachment to circle around to their rear. Once in position however, the detachment fired and charged, driving off the bluecoats. Saunders then proceeded to capture a Union field hospital, rounding up a couple of mobile prisoners and releasing some members of the 28th NC captured earlier that day. Some of the escaping Federals alerted Martindale, who sent half of the 44th NY back toward the area. Saunders beat a hasty retreat. At some point, the Federals abandoned their task and fell back to their original position.21

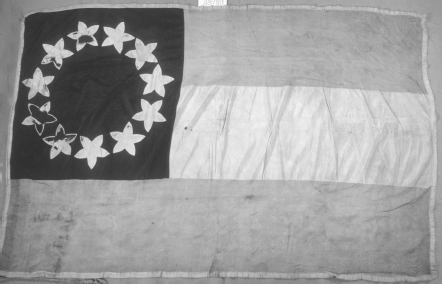

Colonel Robert H. Cowan advanced the 18th North Carolina across an open field during the battle of Hanover Court House.

Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina

As the 33rd dithered about in the woods, the 18th and the 37th Regiments launched their attacks. Colonel Cowan ordered the 18th to fix bayonets and move forward at the double quick. One of the participants said the men had been “told to hold our fire, charge with loaded guns, and capture the battery, if possible.” After passing through a small belt of timber, they entered a large cultivated field. The enemy was reportedly just 200-250 yards beyond the timber. Yet the Confederates soon learned the Federals lay some 600 yards away. Cowan ordered the regiment “forward at charge bayonets” and the 18th started to move across the field. “The artillery was playing upon our men all the while,—throwing shrapnel principally; and soon the Minnie rifles began to assist.” Federal artillery and infantry had no other targets on the field at this point. An officer from the 2nd ME recalled “The enemy … appeared boldly in our front, advancing in perfect order, … the Stars and Bars defiantly flying.” Despite the severity of the fire, the 18th got to within 75 yards of the Federal position. Cowan, with an unaided advance or a retreat equally unthinkable, “halted his line—gave the command to fire—poured in four or five destructive volleys; and under the cover of the smoke threw the regiment into the piece of woods” to his right. There Cowan reformed his lines and continued to fire away.22

“Boys, you have stern work before you. It is no child’s play—do your duty,” admonished Colonel Lee. It had taken the 37th NC much longer to get into position. Undergrowth choked the woods; the adjutant estimated visibility at not more than 30 steps. About the time the Carolinians should have been able to wheel to the right and capture the battery, up rose the 2nd ME, delivering a volley that stopped their advance. Moses Hart attested that he and his comrades had gotten to “within 30 yards of the enemy before we discovered them.” And while the conflict lasted, it “was as fierce as any during the war.” And losses were heavy. “I went into the fight with 60 men and came out with 36 … When we met the enemy we thought there was 1500, but I don’t suppose there were much less than 15,000.” Stalled in the thick woods, the 37th Regiment rose to fire, then dropped to the ground to reload. Federal artillery began to enfilade their right, and the four companies there bent back at roughly right angles to the troops on their left, a maneuver called refusing the flank. Part of the regiment fired toward the artillery, while the rest engaged the 2nd ME. One Tar Heel in the 37th Regiment recalled exploding shells knocking both Colonel Lee and Major Hickerson from their horses. Both Lieutenant Colonel Barber’s and adjutant William Nicholson’s horses were killed.23

Caught in a crossfire, both the 25th NY and the Federal artillerymen began to give way, and soon portions of the 44th NY as well. Had the 33rd NC been able to get into position to sweep down the New Bridge Road, the battle of Hanover Court House might have concluded differently. However, both the 18th and 37th Regiments ran low on ammunition. Moreover, the noise of the battle alerted Fitz John Porter to his blunder. Confederates were in his rear, and Martindale was engaged with them. Porter quickly dispatched several regiments back to Martindale’s position, and these five regiments outflanked both the 18th and 37th and forced them to retreat. Branch had kept the 7th Regiment as a reserve, despite Colonel Campbell’s appeals otherwise. In the gathering darkness the 7th was finally ordered in and delivered several volleys ending the pursuit for the day. Branch’s brigade fell back to Ashland that evening.24

While the 7th and 33rd Regiments sustained few losses, Branch’s three other regiments did not. Total Confederate losses are estimated at 798, including 59 killed, and 210 wounded, 59 fatally. Losses in some community-based companies were tragic. Company G of the 37th Regiment lost James, Joel, John, and William Robnett, possibly brothers from Alexander County. Marvin and James Key, along with their cousin R. J. Key, of the 28th NC were all killed in the fighting around the Kinney farm.25

Doctor Robert Gibbon, the 28th NC’s surgeon, established his field hospital during the battle near a stream, about 200 yards from Kinney’s home. The rest of the surgical team established the brigade hospital at Lebanon Methodist Church. As the Confederates retreated, Branch ordered John Shaffner, the 33rd’s surgeon to move all his ambulatory patients to Ashland. When Shaffner relayed this order to the brigade surgeon at the hospital, three surgeons “disgracefully” mounted up and “left the wounded, ambulances, instruments and supplies lying unprotected in the yard.” Shaffner dismounted, loaded the wagons with medical supplies and “whatever was of value,” along with 30 of the wounded soldiers, and sent them toward Ashland. Overall, 105 of Branch’s wounded fell into enemy hands, including Shaffner while attending to “some of our wounded men, who had been necessarily left behind.” Assistant surgeon W. R. Barham and hospital steward John Abernathy of the 28th Regiment were also captured. Barham apparently escaped while Abernathy was imprisoned at Fort Delaware. The Kinney farm grounds were used later as a hospital. A member of the 28th NC, captured late on May 27, passed by the Kinney farm the next morning. “I beheld an awful sight,” he remembered,”the houses, corncrib, shuck pen, wagon & yard full of wounded, with their cries & moanings from the affect of wounds & the surgeon’s knife & here & there lay a poor soldier who had expired during the night.”26

Lane was forced to abandon a cannon and caisson during the fight between the 28th North Carolina and Butterfield’s brigade. They were later photographed in the camp of the 17th New York Infantry. Library of Congress

The loathsome task of burying the Confederate dead fell upon the Federals. One member of the 5th NY recalled seeing a young Confederate frozen in the act of loading his musket, “his hand was still on the ramrod having rammed the charge about half home.” This same New Yorker recalled burying “a fine looking young fellow about 18 years old, his Bible was in his shirt bosom and we left it there. It was a pity but we had not even an old blanket to wrap around him.” Captain Speer (28th NC) complained he saw members of the 5th NY pillaging Confederate dead taking “money, pocket knives and other little tricks. I felt sorry for these poor men far from home and friends.” Members of the 14th NY dug a trench and buried 25 Confederates together, placing an “orderly sergeant at their head, the post he occupied when alive; at each corner of the plot they placed stakes, and at one end of it, cut on a tree, ‘25 N.C. X killed.’” The Federal dead buried on the field were reinterred not long after the war. The final disposition of Branch’s dead remains a mystery.27

Branch’s biggest loss came from men unable to evade the enemy. Federal forces captured 609 of them, including the 105 wounded. Many of the captured came from the 28th NC, elements of which had been left to fend for themselves after Colonel Lane’s position collapsed. Capt. George Johnston ran into the two companies of the 37th during the retreat. Johnston wanted to turn around and try to cut his way to the main Confederate lines but was persuaded otherwise. His ad hoc command spent the night huddled together, without fires, “the most cheerless, comfortless night” he ever passed, he said. The next morning, Johnston was determined to cross the Pamunkey River. The men made a raft to float their weapons over and strung rifle slings together to combat the current. After several trips, Johnston discovered the majority of his men couldn’t swim, and “dreaded the water more than the Yankees.” Already crossed over, Johnston implored them to cross. Instead they tried to find a boat and were discovered by Federal cavalry in the process. Now Johnston’s men from the opposite bank beseeched him to return, which he did. He was captured with his soldiers. Captain Speer recalled seeing men broken down in every direction as they neared the Pamunkey River. Like Johnston, Speer could have made it over the river, but many of his men could not. Speer remained with them and was captured about dusk on May 27. On May 28 the prisoners marched 18 miles, and another eight miles the next day Numerous groups of Federal soldiers aside the road along the way cussed and berated them “as G. D. dirty rebels, Rebel cut throats, you ought to be hung, have your throats cut, burnt, etc. No one would give us the credit of being humans; [we] did not have horns nor tails but, damn them, they are Rebels.” From White House landing, the prisoners were loaded aboard a steamer, chugged past the wreckage of the USS Congress, and transferred at Fortress Monroe to the Star of the West for a voyage to New York. Confined at Fort Columbus, most were paroled in August.28

James Atkinson of the 33rd North Carolina was captured at Hanover Court House, but managed to escape that evening. He would be wounded at Sharpsburg, Chancellorsville, Reams Station, and Jones Farm, but made it to Appomattox, where he was paroled.

Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina

Many North Carolinians avoided capture and eventually returned to their commands. Captain Nicholas Gibbon (28th NC) led 70 men through the swamp, evading Federal cavalry, only to be accused of abandoning his regiment when he reported to Branch, who apologized to Gibbon a few days later. Lane led other remnants of his regiment through Taylorsville and on to Ashland. He not only discovered Branch gone but also little food to feed his famished men. Several barrels of whiskey were uncovered, though, and Lane ordered one of them rolled out into the street. “I did not have to repeat the order,” Lane wrote, “and you can imagine the effects upon empty stomachs.” Suitably fortified, Lane’s men, “with songs, old rebel yells and a general waving of caps,” struck out for Branch’s main force. Lane asked Branch to send Dr. Gibbon with wagons to transport the sick and broken-down men back. Henry Bennett (37th NC) “managed to slip about till he got seven miles from the battle field, and finally reached our lines in safety,” reporting to his captain, John Ashcraft. Confederates continued to trickle in over the next few days. Portions of the 37th’s Company D who had been sent out on picket and then cut off, arrived back on May 31, many so fatigued wagons were sent to retrieve them.29

Jubilant Union soldiers swept through the former Confederate camp, capturing two company-level flags. On hearing of the battle, McClellan informed his superiors in Washington, D.C. of the victory and claimed the Confederate force completely destroyed. McClellan himself visited the battlefield, calling it “a glorious victory.” McDowell crossed a portion of his command over the Rappahannock River on May 25, and moved towards the Federals at Hanover. Richmond was aware of McDowell’s movement, and of course, Branch’s defeat at Hanover, and on May 28, the papers from the various departments were boxed and ordered to the railroad depot for transport south. But nothing came of McDowell’s move: he never joined the main Federal army, and after their victory at Hanover, Porter’s troops returned to their former position. The pressure from the north was mitigated.30

While his soldiers rested and refitted, Branch was fighting a new battle. An article appeared under the pseudonym “Hanover,” giving a detailed account of the fighting and criticizing Branch’s generalship. Branch’s headquarters were more than a mile from his command, “Hanover” claimed, and the general had missed the entire first part of the battle and failed to reinforce the 18th and 37th which were engaged. So for “the men, company and regimental officers” the battle below Hanover was “a brilliant affair for North Carolinians. Of the rest the public must judge.” Several newspapers in North Carolina did just that. The Spirit of the Age concluded if just half of the reports about Branch’s conduct as a commander were true, “he is very incompetent and so obtuse or excessively vain that” he didn’t even know it. “[H]e ought to be immediately cashiered.”31

The “grossly slandering” letter infuriated the general, and his search for “Hanover” soon succeeded. The newspaper article bore similarities to the official battle report Colonel Lee of the 37th NC had filed, and it wasn’t long before Lee was pressured to reveal his adjutant, William T. Nicholson, had penned the letter, possibly with the help of an officer from the 33rd. When confronted, Nicholson confessed. Branch preferred charges against him, citing his “monstrous and abominable slanders.” Nicholson now felt moved to write a follow-up letter, stating he had subsequently discovered “some facts had been unintentionally misstated, and that certain expressions had been used which might, if unexplained, be constructed to reflect upon the personal bravery or generalship of General L. O’B. Branch.” He went on to add that he now believed Branch had been on the field before the first gun was fired, directing each of his regiments during the battle, and that no less a person than General Lee had sent congratulatory orders to Branch afterwards.32

On June 3, after receiving Branch’s after-action report, Lee wrote approvingly of Branch’s activities at the battle below Hanover Court House. Lee realized Branch had faced superior numbers and asked the North Carolinian to convey to his men “my hearty approval of their conduct, and hope that on future occasions they will evince a like heroism and patriotic devotion.” Undoubtedly, Branch needed the praise. He had fought in two battles as commander of all of the Confederate forces engaged, and had lost both. The press, some of which was already hostile to him, was having a heyday over the accusations of one of his junior officers.33

Dissatisfaction also ran throughout the brigade. Captain Morris (37th NC) wrote home: “we was Defeated through General Branches Bad Management.” Colonel Cowan received so many letters that he submitted his own to the Wilmington Journal, stating he had not been arrested “for using abusive language of Genl. Branch.” His relationship with Branch was “pleasant and friendly,” Cowan said, and he found all the rumors “excessively annoying, but well calculated to impair the efficiency of our Brigade at a time when all our strength is wanted.” But greater events would soon transpire to take the focus off of Branch and his brigade.34

1 OR 5:1086. Including the Valley and Aquia Districts, Johnston had 47,617 men present for duty.

2 Steven Newton, The Battle of Seven Pines, May 31 – June 1, 1862 (Lynchburg, VA, 1993), 104, 109-10; According to Freeman, there were no exact figures for Branch’s brigade, but it “was one of the largest in the Army.” Douglas Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants: A Study in Command, 3 vols. (New York, 1942), 1:201n3.

3 OR 9:471; Order from Branch’s headquarters, April 30, 1862, Lawrence Branch (LB) Letterbook, NCDAH.

4 Clark, Histories, 2:21, 545; J. H. Johnston, Diary, Civil War Collection, NCDAH; Bennett Smith to Wife, May 8, 1862, private collection. At least four were reported injured: Clarence Carter, Fielden Asher, George Norris, and William Helms. Jordan, NC Troops, 9:474, 486, 494, 515. Branch reported on May 10 the 18th Regiment was delayed “by a break down on the R. R.” LB to Richard Ewell, May 10, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA.

5 Bennett Smith to Wife, May 8, 1862, private collection; Biblical Recorder, May 14, 1862.

6 JL to LB, May 10, 1862, LB to Lane, May 11, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA; Hardy, Thirtyseventh, 55.

7 Richard Ewell to Robert E. Lee, May 13, 1862, Heartt-Wilson Papers, SHC.

8 LB to Richard Ewell, May 10, 13, 1862; Richard Ewell to LB, May 11, 12, 1862, all in Brawley, “Branch,” 161; Richard Ewell to LB, 12 May 1862, Branch Papers, UVA; OR 12/3:890-91.

9 LB to Mrs. Branch, May 18, 1862, Brawley, “Branch,”163 (quoted); John Alexander to “Dear Wife,” May 14, 1862, Alexander Papers, UNC/C; JL to Thomas Mumford, January 4, 1893, Mumford-Ellis Papers, DU. Branch never mentioned the idea that his brigade was being used as a distraction, only his frustration about the indecisiveness of Ewell and Jackson.

10 George Johnston diary, June 8, 1862, NCDAH; Joseph E. Johnston to LB, May 19, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA; OR 12/3:898. There is an annotation on the bottom of the note from Johnston that the telegram was sent the day before, but Branch apparently had not received the telegram.

11 Johnston, Diary, June 8, 1862.

12 OR 11/3:537.

13 Eric Wittenberg, “We Have it Damn Hard Out Here:” The Civil War Letters of Sergeant Thomas W. Smith, 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry (Kent, OH, 1999), 34; Johnston, Diary, June 8, 1862; LB to Joseph Johnston, May 24, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA; B. B. Douglas to LB, May 25, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA. Latham’s Battery arrived on May 26 with only “half enough men for the efficient service of the guns and with horses entirely untrained.” Clark, Histories, 2:469.

14 LB to Nancy Branch, May 24, 1862, May 26, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA.

15 Allen Speer. Voices from Cemetery Hill: The Civil War Diary, Reports, and Letters of Colonel William Henry Asbury Speer, 1861-1864 (Johnston City, TN, 1997), 46; OR 11/1:682, 702.

16 Ibid., 741; Speer, Voices From Cemetery Hill, 46. William Mauney (28th NC) writes they moved a half mile down the road but halted before reaching the mill. William Mauney, Diary, May 27, 1862, Kings Mountain Historical Society, Cleveland County, NC.

17 Johnston, Diary, June 8, 1862.

18 OR 11/1:743; Rochester Democrat and American, June 10, 1862; Speer, Voices of Cemetery Hill, 50-52.

19 Speer, Voices, 52-53; OR 11/1:744.

20 Janet Hewett, et. al., eds., Supplement to the Army Official Records, 100 vols. (Wilmington, NC, 1994-2001), 2:367; OR 11/1:703-704; the 37th Regiment only had seven companies. Two companies had been sent out on picket, while a third was detailed to guard the regimental baggage.

21 Joseph Saunders to mother, June 6, 1862, Saunders Papers, SHC.

22 Philadelphia Times, October 20, 1883; Wilmington Journal, June 12, 1862; OR 11/1:741.

23 Wilmington Journal Weekly, June 12, 1862; Weekly Catawba Journal, June 19, 1862; Spirit of the Age, June 9, 1862; Raleigh Register, June 7, 1862. One account says Hickerson gave his horse to Barber.

24 Schenck wrote Branch’s brigade “so hurt the Northern division opposing them that there was no immediate pursuit.” Martin Schenck. Up Came Hill: The Story of the Light Division and its Leaders (Harrisburg, PA, 1958), 37; Weekly State Journal, October 1, 1862. According to an article on Branch after his death, Campbell sought out the general the next day and “magnanimously told him that he had done the right in holding him in reserve.”

25 The story of the Robnett brothers being killed is often repeated. Some family members believe William and James Robnett were brothers, as were cousins Joel and John C. Robnett. Email, Bill Robinette to author, October 20, 2010, in my possession; Casstevens, The 28th North Carolina Infantry, 239.

26 The Catawba Weekly Journal, June 10, 1862; Louis Shaffner, “A Civil War Surgeon’s Diary,” North Carolina Medical Journal (September 1966), 23:410; Jordan, NC Troops, 8:111, 112, 9:120; Speer, Voices from Cemetery Hill, 57.

27 Stevens [to unknown], June 11, 1862, quoted in Brian Pohanka, Vortex of Hell: History of the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry (Lynchburg, VA, 2012), 230-31; Speer, Voices, 59; Oneida Weekly Herald, June 17, 1862.

28 Johnston, Diary, June 8, 1862, NCDAH; Speer, Voices, 56, 61.

29 Nicholas Gibbon, May 1862, Diary, Nicholas Gibbon Papers, UNC/C; Charlotte Democrat, July 1, 1862; Biblical Recorder, June 11, 1862; JL to Thomas Munford, January 4, 1893, Lane Papers, AU; JL to WB, May 29, 1862, Branch Papers, UVA.

30 Stephen Sears, ed. The Civil War Papers of George B. McClellan: Selected Correspondence, 1860-1865 (New York, 1992), 279; for more information, see Hardy, The Battle of Hanover Court House. The captured flags belonged to Company E, 12th NC State Troops, and Company D, 45th GA.

31 The Spirit of the Age, June 9, 1862.

32 Clark, Histories, 1:24; “Charges and Specifications against William T. Nicholson …” n.d., Branch Papers, UVA; The Weekly Catawba Journal, June 19, 1862. Apparently, the charges against Nicholson were dropped.

33 OR 11/1:743.

34 William Morris to “Deare Companion,” May 30 1862, Morris Papers, SHC/UNC; Wilmington Journal, June 26, 1862.