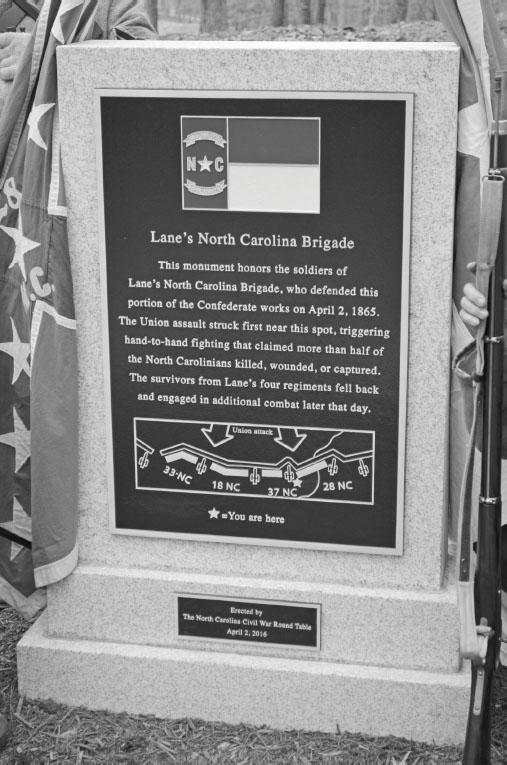

On March 19, 2016, a monument was dedicated to Lane’s brigade at Pamplin Historical Park near Petersburg, Virginia. Brian Duckworth

“[O]ne of the finest fighting records.”

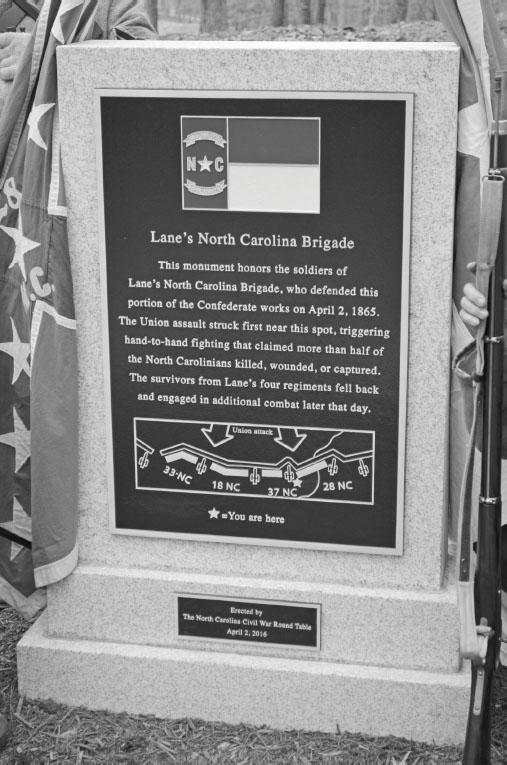

In March 2016, a monument was dedicated to the Branch-Lane brigade at Pamplin Historical Park in Petersburg, Virginia, commemorating the brigade at the spot where the breakthrough took place on April 2, 1865. Efforts were also underway to raise funds for the conservation of Branch’s headquarters flags. After 150 years, the Branch-Lane brigade finally seemed to be getting the recognition Riddick Gatling, Jr., sought in 1888 when he lamented the lack of a history for his comrades.

The Branch-Lane brigade was renowned during the war, with as illustrious a reputation as the Stonewall Brigade or the Iron Brigade. In September 1862, Raleigh’s Semi-Weekly State Journal said that the brigade “had gained a dangerous notoriety, for, whenever Jackson or A. P. Hill has a desperate undertaking Branch’s men are ordered in.” After documenting the various engagements the brigade had fought in just six months, the writer concluded, “We trust enough of these glorious fellows may yet be spared to enjoy the well-earned reputation of their brigade.” Unfortunately, a vast segment of this extraordinary group did not live to see the end of the war, and many who did survive could not merely enjoy the brigade’s impressive reputation. Rather, they often had to struggle for the recognition they justly deserved, both during and after the war, despite being frequently praised.1

On March 19, 2016, a monument was dedicated to Lane’s brigade at Pamplin Historical Park near Petersburg, Virginia. Brian Duckworth

Even after the war, friend and foe alike continued singing the brigade’s praises. Former Federal officer Augustus C. Hamlin, in his book on the battle of Chancellorsville, wrote: “The history of this command [Branch-Lane brigade], under its dauntless leader, throughout the war, and ending at Appomattox, will always be admired and respected by those who believe in American manhood. And the student who seeks to discover a higher degree of courage and hardihood among the military organizations of either army will look over the true records of the war for a long time, if not in vain.”2

That acclaim continues into the twenty-first century. Historian Alfred Young III, to cite just one, examining the numbers of men in Lee’s army during the Overland Campaign, believed Lane’s brigade had “one of the finest fighting records in the Army of Northern Virginia.”3

There were of, course, detractors, former soldiers like Walter Taylor, and at times, historians like Douglas Southall Freeman. The latter contended Lane should have notified Longstreet on July 3 that his line did not extend to cover the entire distance behind Pettigrew’s division. In Lee’s Lieutenants, his three-volume history of the leadership of the Army of Northern Virginia, Freeman fails to mention any contribution of Lane’s brigade at Spotsylvania Court House on May 12, assigning the salvation of Lee’s army to John B. Gordon’s brigade; Freeman also neglects to cover the brigade’s role at Battery Gregg on April 2, 1865. He writes much more sympathetically of General Branch. Hanover Court House was “in no sense discreditable to Branch, and Branch’s failure to support Longstreet at Frayser’s Farm was due to the fact Branch had his hands full on his own front.”4

In the end, the Branch-Lane brigade played an enormous role in the ordeals of the Army of Northern Virginia. Battles such as Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas, Spotsylvania Court House, and Reams Station might have ended differently had it not been for these Tar Heels. With victories, however, came battlefield defeats, like Hanover Court House, and the breakthrough below Petersburg on April 2. And the death of the beloved Jackson at the hands of the brigade cast a pall over its otherwise stellar history. Perhaps it also explains why, despite its many accomplishments, the Branch-Lane Brigade has not always enjoyed the attention its reputation deserves.

“Bravest of the brave” and a brigade with “a dangerous reputation” were terms frequently used to describe the Branch-Lane brigade. Of the 8,975 men who served those four years in the brigade, at least 3,151 died while in service—1,197 on the battlefield. The others died of disease, in prison, or of unknown causes. In the end, the Tar Heels in the Branch-Lane brigade were not necessarily braver than the men of the Stonewall brigade or of Kershaw’s brigade, but these Tar Heels most certainly did earn their dangerous reputation.

1 Semi-Weekly State Journal, September 17, 1862.

2 Hamlin, Chancellorsville, 114.

3 Young, Lee’s Army, 139.

4 Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants, 1:220, 651; 3:184, 388-410.