![]()

![]()

WE AGREED THAT while Miriam would set about charming the various butchers, bakers, fishmongers, greengrocers and the icemen of Lewes, in the hope of finding someone who might have seen something suspicious on the morning of 6 November, I would accompany Morley to Lizzie’s school, where he had been scheduled to give a talk on the unprepossessing subject of ‘Sussex: Then and Now’.

Wherever we went on our travels, Morley always insisted on visiting the local schools and colleges to deliver some such encomium or to award some prize: in many ways, schools and colleges were his natural territory. In the grand country houses and literary salons of England he was often treated as something of an adornment, or an amusement, the pet autodidact, the rare working-class specimen of the genus writer. Specialists and scholars had little time for him or his work, regarding what he produced as little more than cheap entertainment for the masses. They were not entirely wrong. R.G. Collingwood he was not, but then who now reads R.G. Collingwood? There were – I’ll admit, as the author of more than one or two of them – some inaccuracies in the books. Quotations often came closer to paraphrase than they did to absolute accuracy. Broad generalisations often took the place of careful discussion. He was prepared to swoop low in his rhetoric, just as much as he was prepared to swing ludicrously high. Often humourless, and entirely lacking in satirical aim and intent, he could yet be enormously funny and piercingly keen in his insights and ideas. Children, obviously, loved him.

Mr Johnson, the headmaster of the school, was a man who rather strained towards a military bearing, I thought: ramrod, flinty, no-nonsense. Barrel-shaped, red-faced, he struck one as the sort of man who might have a full set of Blakey’s in his shoes: heel plates, toe plates, dozens of treble hobs; a strider and a stamper; a strict disciplinarian; the sort of chap who prided himself on taking no nonsense, no prisoners, and little or no pleasure in anything, like so many teachers back then, sharp of tongue and dull of mind. He explained to us on our arrival, after a perfunctory handshake and welcome, that though many of the children were aware of the death of Lizzie Walter, he and his fellow teachers were not discussing the exact circumstances of her ‘demise’ – his word – since so many of the children had learned to swim in Pells Pool. He would be grateful, he said, if we made no mention of recent events.

‘Of course,’ said Morley, clearly offended that anyone would assume that he would make mention of such a terrible tragedy to young children. ‘Under no circumstances, sir.’

‘We don’t want to put them off getting into their swimming togs.’

‘Indeed we don’t,’ agreed Morley.

‘Healthy and wholesome exercise,’ said the headmaster, jutting out his chin, puffing out his chest, and straightening his posture.

‘And a sort of performance, of course,’ said Morley, rather pointedly. ‘Of the self, in public.’ He knew a fellow spoofer when he saw one.

The talk took place in the school hall, with Morley encouraging the children to persevere, to study hard, to be good Christians and citizens: it was boilerplate stuff, yet in Morley’s hands, and in front of this audience, it seemed to have an electrifying effect. There was barely a fidgeter in the hall, and no call upon the teachers to impose discipline or to remind anyone not to do this or that or the other. The children sat, cross-legged, arms folded, heads unscratched, pigtails unpulled and noses entirely untended, staring up at this man whose words they had only previously read, or heard read aloud from books and newspapers. It was as if the good Lord Himself had suddenly stepped forth from the pages of the Children’s Bible – in tweeds, brogues and with a broad Empire moustache. Underneath it all, underneath the words and the outfit, the manner, in his speech, as in his prose, through its many varnished layers, you could still discern in Morley the figure of the child. Which of course is why children loved him: he was exactly like them.

During my many years with Morley, he spoke rarely of his own childhood and upbringing – only ever, in fact, when speaking to children. I suggested to him on a number of occasions that he should consider writing about his memories of childhood but he was always amazed at the suggestion. Surely every word he wrote stood as a testament to his childhood? There was no need for further elaboration. Like a child, he was curiously uninterested in his own past: he was somehow innocent of himself. The past made little or no claim upon him, though this morning he spoke movingly to the children of growing up in the sawmills and timber yards of Norfolk, full of energy and optimism, and how, without opportunity for education or advancement, the world had become his textbook and his teacher.

People often tried – adults, that is – to penetrate to the true meaning of Morley and his work, to try to work out what he was really all about. Because he appeared so self-contained and was not susceptible to self-revelation or to self-analysis, it meant that he could sometimes seem cool and aloof and uninterested in others. Yet the opposite was the case. He really was, very simply, like a child, a part of and yet entirely apart from the realm of adult thoughts and concerns. There was always more association than logic in his thinking, for example, his speech and his sentences that morning leaping from one to another, with the carefree joyousness of a small boy kicking a stone down the road. Capable of extraordinary absorption in a subject, he was also infinitely distractible. The children clearly recognised in him one of their own. They recognised that he was not using them for any purpose: he was simply enjoying their company.

The teachers were in fact the first to fidget. I noticed the early signs – some tell-tale eye rolling – when Morley embarked upon a story about a trip he had once made to Iceland, during which he claimed to have met the huldufólk, the hidden folk.

‘Sussex is thick with little people like that, with fairies and stories of fairies, just like Iceland. The Pucks and the Pooks and the fairy rings on the Downs.’

The teachers began to exchange disapproving glances.

‘The little people are written into the landscape in Sussex as perhaps nowhere else, children – Iceland excepted. You have Pookhill, Puxsty Wood, Puckscroft—’

A little chap put up his hand.

‘Yes, young man?’ said Morley.

‘Pucksroad,’ he said.

‘Very good!’ said Morley. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Sidney, sir. Pucksroad,’ he repeated.

‘You live on Pucksroad?’

Sidney shook his head, suddenly aware of the sentinel stares of his teachers.

‘No?’ said Morley sympathetically. ‘Near Pucksroad? By Pucksroad? You made it up?’

He nodded.

‘Good. Good! Stand up!’ said Morley.

Sidney stood, abashed.

‘A plucky little chap from Pucksroad!’ said Morley. ‘Well done! Let’s give him a round of applause.’

The children erupted into applause.

Sidney looked like the sort of little chap who was probably unaccustomed to the applause of his classmates: he looked indeed the sort of little chap who might more usually have spent much of his time being pummelled by his peers. He now beamed in the glow of their regard.

‘Very good,’ said Morley. ‘Now, sit down, Sidney,’ and Sidney sat down. ‘In Iceland,’ continued Morley, ‘they’re the huldufólk. In Ireland they’re the leprechaun. What other names do you have for the fairies here? If you tell me, I shall write their names in a book.’

Lots of little hands shot up.

Morley picked out a young girl.

‘Yes, my dear, what do you call the fairies?’

‘Pharisees, sir.’

‘Pharisees? As in the Pharisees?’

‘Pharisees,’ said the girl again.

‘Wonderful.’ More applause. ‘Sefton,’ he said to me. ‘Make a note.’ Which I duly did. More applause. More disapproving glances.

I noticed then that there was a sort of tapping that continued on beyond the applause. Sitting at the front of the hall with Morley, I could see what neither the children nor the teachers could, but which everyone could hear, which was the headmaster, in his gown, ramrod, flinty, no-nonsense, rocking backwards and forwards on the Blakey’s on his shoes, and tapping at his watch, indicating that it was time for Morley to conclude. Morley glanced at his own watch. And then his other watch. And then his pocket watch. He had been asked to speak for half an hour. He had so far spoken for only twenty minutes. The headmaster had made a serious miscalculation: you didn’t challenge Morley over time.

The next ten minutes – exactly – of Morley’s talk were a bravura performance, packing in history, economics, natural history, art, science, music, agriculture, and encompassing encomiums to the Sussex lane (which are ‘haunted by the ghostly swoop of the barn owl at night’, apparently), the Sussex stook (a term which was entirely new to me, but which seems to have something to do with the harvesting of corn), tales of Sussex grey ladies and black dogs (which sounded similar to the tales of grey ladies and black dogs we encountered in every other county we visited, but anyway), and a tribute to the Greyhound Inn at Tinsley Green, which had hosted – who knew? – the World Marble Championship since 1932. Details about the marble championship went down particularly well with the children, all of whom solemnly vowed to practise their marble skills in time for the next championship, to bring glory to their home county, Morley leading them in a chant of ‘Marbles! Mibsters! Ducks and Taws!’, the headmaster’s tapping effectively drowned out by the sound, which was presumably Morley’s intention.

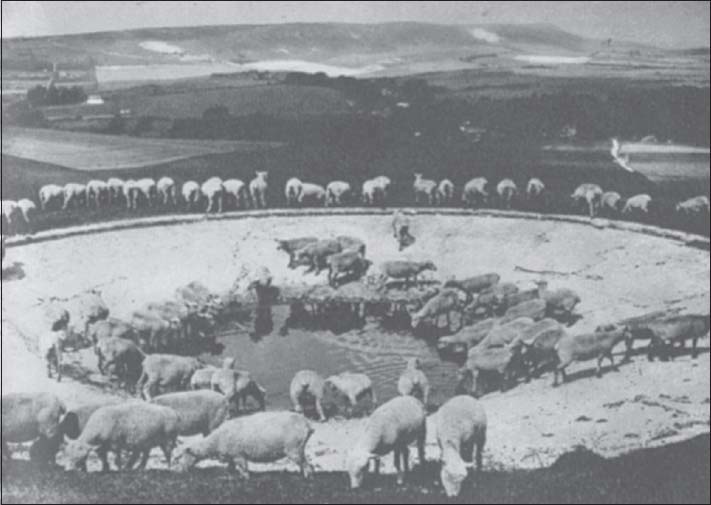

With just minutes of his allotted time to go, Morley concluded with what can only be described as an improvised prose poem on the wonders of the Sussex dew pond, which might easily have come from the lips of Edith Sitwell herself – if, that is, Dame Edith had had any knowledge of Sussex country crafts, country lore and primitive engineering. (Readers keen to experience this prose poem for themselves in all its glory, and indeed at much greater length, can do so by reading ‘The Sussex Dew Pond: A Brief History’ in the Countryman, January 1938.) Like most people, I suspect – and certainly like the children in the school hall, whose attention was, at this point, finally beginning to wander – I was unaware of the history of the construction of these very particular and peculiar Sussex structures, these ‘mirrors of the Downs’ as Morley described them, these ‘wonders of nature and culture’, these ‘testaments to the skills and determination of the Sussex men and women of yore’. I had no idea, for example, that the holes, having been excavated long ago, had been laid with chalk, to be crushed by oxen and carts drawn around and around in circles, with water being continually doused upon the surface until the mush resembled a smooth thick cream and was left to harden like cement. Sensing that he had perhaps rather lost his audience with his story of the dew pond, Morley concluded with a final flourish, asking how many Cinque Ports there were. When came there no answer he turned to me.

A Dew Pond on the Downs

‘Sefton?’

‘Five?’ I hazarded a guess.

‘Seven!’ cried Morley, much to the children’s uproarious hilarity, though none of us really knew why, except we were perhaps all relieved that it was over.

Very occasionally I heard Morley despair of his skills and capacities. He would sometimes repeat the criticism often made of him by others: that by lecturing and writing so much, and about so much, and so fast, with such enthusiasm and abandon, he somehow betrayed himself as essentially lacking in seriousness. His critics seemed to believe that education should be the product of pain and anguish, yet with him the work was always the product of joy. It also counted against him, even among those one might have expected to have approved – teachers, for example – that he sought only to educate the young, the poor and the undeserving. It was felt to be rather beneath the dignity of a serious writer to want to educate and encourage those who were without education and in want of encouragement. Even those who had benefited from his work in their own lives, as they continued on in their journey towards knowledge seemed to feel that he was merely a starting point or an early staging post along their journey’s way. Morley and his work were therefore often abandoned and stranded in that very place that no serious middle- or upper-class writer ever wishes to inhabit: neither quite literature nor simply entertainment, destined to be merely a memory, as something one used to read. As he concluded his talk to the children that morning, I realised that as well as welcoming them into his world he was also simultaneously bidding them farewell.

After the talk, as the headmaster was briskly escorting us out of the school down one of those stinky, interminable and forbidding school corridors that seem to grow no less stinky, interminable and forbidding the older one gets, Morley asked if he might rest and recuperate for a few minutes before setting off again. He seemed suddenly and uncharacteristically tired.

‘Yes, of course,’ said the headmaster. ‘You must come to my office.’

‘No, no, we wouldn’t want to disturb you,’ said Morley. ‘You are clearly a very busy man, Mr Johnson. Perhaps we might just rest in an empty classroom, if you have one,’ said Morley. ‘Just for a few moments.’

‘Well,’ said Mr Johnson. ‘It would be no trouble to—’

‘Ah, here we are,’ said Morley, pushing open the door to what was indeed an empty classroom and stepping wearily inside, almost as though he were about to collapse. ‘Perhaps I could ask your secretary to bring us some tea?’

‘Yes, that’s—’

‘No milk or sugar for me, thank you,’ said Morley. ‘And my assistant will have—’

‘I’m fine, thank you,’ I said.

‘Very good,’ said Morley. ‘Goodbye, Headmaster.’ And he ushered him out the door and into the corridor.

As soon as the sound of Mr Johnson’s footsteps had disappeared down the corridor, Morley – apparently miraculously restored to his former self – leapt up and dragged a desk across the door.

‘What on earth are you—’

‘No time for questions, Sefton, we’ve got about eight minutes, by my calculation.’ He checked both his watches. ‘Let’s just hope the secretary knows how to make a proper pot of tea, eh? Come on, Sefton, kettle’s on.’

As he explained to me later, Morley, on Molly’s insistence, in an attempt to clear Henry’s name, had embarked upon his own investigation into the death of Lizzie Walter, and had quickly decided that the best approach was not to seek evidence or clues of any unusual activities on the night of 5 November, but rather to study and try to understand Lizzie’s habitual behaviour – thus, beginning in her workplace. There was likely to be only one empty classroom in the school we were visiting that morning, he reasoned, which would be the classroom that had been used by Lizzie. By creating a simple diversion we might have a few moments to see if there was anything interesting in her classroom. In fairness, as a plan, it made about as much sense as Miriam and I drawing up a long list of possible suspects and witnesses from among the early morning men and women of Lewes.

Our first challenge was to somehow crack into the locked stationery cupboard behind Molly’s desk, a classic piece of school furniture, a big old beast of a thing, of the kind small boys have since time immemorial enjoyed locking each other inside.

‘Now,’ said Morley triumphantly, producing from an inside pocket a thin sliver of metal he kept concealed for just such purposes – though, alas, it turned out to be the wrong tool for this particular purpose.

‘Wrong tool,’ he said.

‘A workman never blames his tools, Mr Morley,’ I said.

‘Pot’s warming, Sefton,’ he said, consulting his watches again. ‘No time for levity. Chop chop. Where would you leave a key?’

‘Under a plant pot?’ I said.

‘That’s no good,’ said Morley.

I pointed at the many plant pots lined up on the windowsill in the room.

‘Aha!’ said Morley.

There were no keys under the plant pots.

‘So, if you had the keys and you didn’t want the children to get hold of the keys,’ said Morley, ‘where would you …?’

He reached up by the side of the blackboard and sure enough produced a keyring from a small hook, half concealed behind the frame of the board.

Within seconds, we had the stationery cupboard open, only to find that it was indeed a stationery cupboard full of stationery, rather than a clue to the inner workings of Lizzie Walter’s mind. Morley became momentarily distracted by the stationery – he was an obsessive when it came to the paper and the pens and the inks and the nibs required for the smooth running of his writing business. Since I was responsible for the smooth running of the smooth running of his writing business, I too became something of an expert in such supplies: we had accounts and orders with the biggest stationers in London, Germany, Paris and Geneva. (It was also my job to update weekly Morley’s endlessly updated Catalogue of Items Read, which required a very particular layout, with bibliographical references, quotations and questions, as well as the notes and a series of marginal keywords: the ledgers in which we recorded this information had to be specially imported, at great expense, from Milan.) The stationery cupboard at the King’s Road School in Lewes was far from a treasure trove, but it was more than enough to fascinate Morley, and for me therefore to have to remind him of the urgency of our search.

‘Mr Morley,’ I said, looking at my own watch. ‘I think the brew’s on.’

‘Ah! Yes!’

He turned towards Lizzie’s desk: neat, tidy and paperless.

‘Does that look like a schoolteacher’s desk to you?’ he asked.

Before I could answer he had jemmied open the locked desk drawers with his thin sliver of metal, which indeed was the right tool for this particular purpose. Inside, the drawers were crammed with pencils, pens and paper.

There is, alas, only one phrase to describe what we did next, though Morley would object to the cliché: we rifled through the contents of the drawers.

Mid-rifle, as the door of the classroom noisily banged into the desk that had been wedged against it, Morley lifted up the back vents of my jacket, thrust some papers into my trouser waistband, and rushed over to the door.

‘Apologies!’ he called. ‘Apologies! Didn’t want to be disturbed. Just taking a quick nap. I was quite overcome.’

The desk pulled away, Mr Johnson’s secretary appeared at the open door, holding a tray with a cup of tea.

‘Miss?’

‘Hunter, sir.’

‘Miss Hunter, thank you so much,’ said Morley. ‘That is so kind.’

‘That’s perfectly all right, sir.’

Miss Hunter gazed into the room, as if bewitched, but would not cross the threshold.

‘I’ll …’ She was staring at the desk. Not at the drawers, which we had been rifling, but behind the desk, in the area in which a teacher might be seated, or standing at the blackboard.

‘Ah, yes. It must be difficult, of course,’ said Morley.

‘This was her room,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ said Morley. ‘A terrible loss for you. For the whole school.’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you know her well, Lizzie? Miss Walter, I mean.’

‘We used to go out together,’ said Miss Hunter. ‘Me and my fellow and her with hers.’

‘Henry?’ said Morley.

‘Who?’

‘Henry? The American. Son of Molly Harper, the singer?’

‘No. Her boyfriend was Michael, up at the museum.’

‘The man from the museum?’ said Morley. ‘Which museum?’

‘The town museum. They’d been going out for a long time. I thought they were engaged, but you know how these things go.’

‘Alas,’ said Morley. ‘I do. You have been most helpful. Thank you. Sefton?’ He nodded to me that we should leave.

‘What about your tea?’ asked Miss Hunter.

‘No time, I’m afraid, Miss Hunter. We have much to do in Lewes. Thank you again.’

Young scholars