![]()

![]()

‘HOW WAS YOUR SHOPPING then, chaps?’ asked Miriam, once we were back at the hotel.

‘Excellent,’ said Morley. ‘Excellent. Look at this magnificent trug.’

‘Hmm,’ said Miriam. ‘Yes. Quite magnificent, Father. Fabulous, in fact. Astonishing.’

‘Now now,’ said Morley.

‘Was that really the best use of your time, though, Father? Trug shopping? Fiddling while Rome burns?’

‘I think if you’re referring to the proverbial, apocryphal story of Nero, Miriam, you’ll find that Rome burned around AD 64, fiddles weren’t invented for another millennium, and that anyway Nero wasn’t anywhere near Rome when it was burning.’

‘But my point still stands.’

‘It would, my dear, except for the fact that we managed to make some considerable progress on important matters.’

‘Which important matters?’

‘I think we’ll save that for the moment, Miriam. We need confirmation on a couple of things.’

‘I think we might need confirmation on more than a couple of things, Mr Morley,’ I said. I still had no idea in what direction Morley’s investigation was headed.

‘Well, let’s get to the museum, shall we, have a quick word with this chap, Lizzie’s boyfriend, and then we can regroup and see where we’ve got to?’

![]()

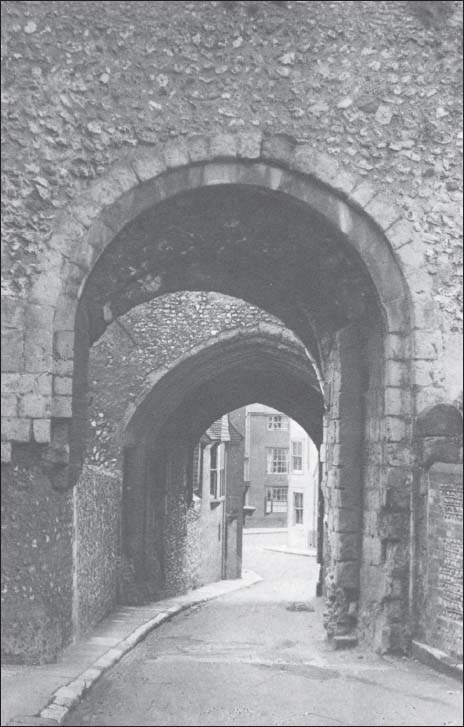

The museum in Lewes is by Lewes Castle, which is entered by and through a magnificent barbican which, according to Morley in The County Guides: Sussex, is highly sketchable. So highly sketchable, indeed, that before we entered the museum, Morley paused to sketch it.

‘Look at that flint work, Sefton.’

‘Indeed,’ I said.

The flint work looked exactly like flint work.

One of Miriam’s rules for dealing with her father, which she had explained to me when we first set out on our adventures together, was never to let him get on to flint work. There were a lot of other forbidden topics, it has to be said, ranging from anthropometrics to Ottoman history. (Notably, in the context of our trip to Sussex, we were supposed never to allow him to discuss Piltdown Man. Morley was with Ramström of Uppsala, in believing that though the skull may have belonged to prehistoric man, the jaw definitely belonged to an ape. Piltdown Man was an absolute no-no.) The trouble with Morley was that he was simply too curious about everything, which was an affliction rather than a skill or a gift, and which meant that, say, the study of flint work might easily occupy as much of his time and money as, say, the study of world political and economic systems, or the future of farming in an age of scarcity.

Some Highly Sketchable Flint Work

‘He is obsessed with blasted flint work, Sefton. Knapping, coursing, cobbling and goodness knows what else-rying.’

Back at Morley’s home in Norfolk I had indeed already enjoyed many conversations with him on the subject of flint knapping, so I always did my best, wherever we were, to steer him away from flint work. On this occasion, however, Lewes Castle had caught me off-guard. From bitter experience, I knew that the only thing to do, once the subject of flint work was introduced, was to try to steer him immediately into a conversation about some other building material. Exactly which building material, and indeed what was the building, was irrelevant.

‘Mmm,’ I said, looking around. ‘Look, Mr Morley—’

‘Yes, black-glazed bricks,’ said Morley, nodding towards a building, which I hadn’t even noticed, to our left.

‘Yes.’

‘But the flint work, Sefton!’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘But what about the …’ I pointed randomly towards the top of the barbican.

‘Machicolation?’ said Morley.

‘Yes, exactly, the …’

‘Machicolation,’ repeated Morley. ‘I am right in thinking that you did study history at school, Sefton?’

‘I did, Mr Morley, indeed.’

‘And French?’

‘And French, sir, yes.’

‘So, machicolation, from the French mâchicoulis, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, yes, I think so.’

‘And it is therefore …’

‘It is …’

‘The opening between the supporting corbels of a battlement. There, see?’

I eventually saw what he was pointing to.

‘Yes, yes,’ I agreed.

‘Machicolation. Through which rocks or boiling oil can be dropped on attackers at the base of the wall.’

‘Lovely,’ I said.

‘Very common in France,’ said Morley. ‘Less so in England. Which is what makes it so remarkable.’ He then went on to explain the differences between English and French fortifications and defensive tactics during the Middle Ages.

But at least we avoided the flint work.

Lewes Museum was housed in the Barbican House, a big red brick building, which according to the small brass plate outside was officially the home of the Sussex Archaeological Society. We entered the building through a magnificent stone-floored hallway, hung with paintings and with some rather half-hearted displays of pottery ware and old flint arrow heads in half-empty display cabinets: a typical English provincial museum. So typical, in fact, that, typically, there didn’t seem to be anyone about.

‘Hello?’ called Miriam. ‘Anyone there?’ There came not a sound, not a peep, not a creak, not even the slightest museum echo. ‘Hello? Anyone in? Shop?’

Morley was already venturing up the ancient staircase, taking the steps two at a time.

‘This way!’ he called.

‘Father!’ said Miriam.

‘This’ll be the way,’ he said.

And he was, as so often – when he wasn’t utterly incorrect – absolutely correct.

At the top of the house there was a vast room with great tie-beams. ‘Look at the tie-beams, Sefton!’ said Morley, and look indeed I did, and I can confirm that the tie-beams of the Barbican House in Lewes are truly great tie-beams. The room resembled a library, though with rather fewer books, and at the far end, working at a table with a heavy serge cloth upon it, haphazardly piled with books and papers, and looking for all the world like Dürer’s St Jerome in His Study, though without the lion, and some years younger, and with a full head of hair, was Michael Anderson, Lizzie’s boyfriend – the rather weak-featured fellow we’d already met at the dinner at the White Hart.

‘I really don’t see what she sees in the chap,’ whispered Miriam to me.

Michael, for his part, was delighted to see us.

‘Mr Morley!’ he said, getting up from his chair. ‘How delightful. And Miriam. And …’

‘Stephen Sefton,’ I said.

‘Yes, of course, the assistant.’

‘We couldn’t leave Lewes without a look round the museum,’ said Morley.

‘Well, I am truly honoured,’ said Michael.

‘So you are the director? The curator of this …?’ asked Miriam.

‘I am officially employed by the Sussex Archaeological Society, which is one of the nation’s great ancient societies.’

‘How old is the Sussex Archaeological Society, Mr Anderson?’ I asked, reaching instinctively for my German notebook, in the full knowledge that if I didn’t quickly start taking notes, Morley would soon be asking me to take a note, so I might as well start.

‘We were founded in 1846.’

‘Not that ancient, then,’ said Miriam. ‘Not that much older than Father.’

‘Thank you, Miriam,’ said Morley.

‘We were founded after the discovery of the ruins of the Cluniac Priory of St Pancras at Southover, when the railway was being developed. You know the story of the priory of course?’

‘Henry VIII decided he had the right to the priory’s wealth, and Thomas Cromwell had it destroyed?’ said Miriam off-handedly.

‘Yes,’ said Michael, with something of a snort. ‘In a nutshell I suppose that’s it.’

‘And how did you end up here, Mr Anderson, in this wonderful place?’ asked Morley. ‘You’re not local? I’m not picking up the accent.’

‘The house once belonged to my great-uncle, actually.’

‘Ah,’ said Miriam.

‘But he – having no children – was succeeded by my father, who was the son of his brother, who was an 8th Hussar, reputed to be the bravest officer in the British Army.’ He gave a bitter little laugh.

‘Very good,’ said Morley.

‘And who as a young subaltern eloped with the colonel’s wife. Hence me, and hence …’

‘I see.’

‘I was a teacher at the Berlitz School in Brussels for a while, and then I returned to London, where I was living in Chelsea.’

‘Well done,’ said Miriam.

‘I then ended up in Crawley, whose only distinction is that it’s halfway between London and Brighton, but it allowed me to pursue my studies.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Miriam. ‘Bad luck. Crawley’s awful.’

‘I don’t think Crawley’s that bad, Miriam,’ said Morley.

‘No, no, you’re quite right, Miss Morley,’ said Michael. ‘I’m afraid Crawley is rather Limbo-like. But, by various means, I ended up back here in Lewes. So it’s a sort of homecoming, I suppose.’

‘And what’s your specialism, may I ask?’ asked Morley.

‘Actually,’ said Michael, ‘I’m not so much an archaeologist as a geologist. I’m a bit of an expert in flint.’

‘Oh no,’ groaned Miriam.

‘Flint!’ said Morley. ‘Really? Marvellous!’

‘A fellow enthusiast?’

‘Absolutely!’ said Morley. ‘The great sedimentary rock.’

‘Lot of competition?’ asked Miriam.

‘A naturally occurring mineral that can be used as a weapon and as a tool?’ said Morley. ‘A grey shapeless shape that yet contains within it darkness and sharpness and edge? Can you name another such sedimentary rock?’

Miriam gave a loud groan.

‘Do you have a cigarette, Sefton?’ she asked.

‘Well, you’re certainly in the right county for flint, Mr Morley,’ said Michael. ‘The great hill called Cissbury Ring is of course one of the great repositories of flint in England.’

Miriam looked at me, appalled.

‘Anyway, Mr Anderson, perhaps you’d give us a tour?’ said Miriam, desperate to avoid any more flint talk.

So Michael began to show us around.

‘Now, do you want to start with the shield bosses, or perhaps some brass rubbings? We have an extraordinary collection of old ankle fetters. Take your pick.’

‘Be careful what you wish for,’ I whispered to Miriam, who was now in full fug and furiously smoking.

‘I noted your flint arrow heads downstairs,’ said Morley.

‘Oh yes,’ said Michael. ‘Plenty of flint arrow heads. But I suppose for the general public the most remarkable exhibit is probably the mummified hand of a murderess – everyone wants to have a look at that.’

‘Oh, yes!’ said Miriam. ‘Let’s have a look at the mummified hand of the murderess.’

‘But if we perhaps come over here first, we have a little display – that I must say I’m rather proud of – about Togidubnus, who was a local chieftain who was friendly with the Romans …’

The display consisted of some handwritten documents and some black and white photographs laid out on a small green baize-topped table.

Miriam yawned.

‘Downstairs, miss, there are lots of etchings and some very fine watercolours—’

‘If you think because I’m a woman I’d be more interested in etchings and watercolours,’ said Miriam, blowing smoke in his general direction.

‘No, not at all,’ said Michael. ‘I just thought—’

‘Apologies for my daughter,’ said Morley. ‘If she’d been born a few years earlier she’d doubtless have been a suffragette.’

‘Ah, well, you might be interested in our little display on radical Lewes then,’ said Michael, leading us towards another green baize-topped table, similarly set up with some typewritten documents and copies of engraved portraits.

‘The author of The Rights of Man?’ said Morley, indicating one of the engravings.

‘Correct. Though perhaps more famous for our purposes here in Lewes as the winner of the Headstrong Book, which was an old Greek Homer awarded to the most obstinate haranguer at the White Hart evening club, where we were the other evening.’

‘You don’t have the original Headstrong Book?’ asked Morley.

‘Alas, no,’ said Michael.

‘That’s a shame,’ said Morley. ‘I know just the person we might award it to.’

‘Very funny, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘Paine’s home is just off the High Street,’ said Michael. ‘Almost opposite St Michael’s, if you want to visit. You can’t miss it.’

‘Oh, we shall definitely visit Paine’s house,’ said Morley.

‘We shall definitely not,’ said Miriam to me quietly.

‘Now Paine I am familiar with,’ said Morley. ‘But these other Lewesians?’

‘Oh gosh, yes, we have a tremendous radical history here in Lewes. Home to Dissenters, obviously, Quakers and Baptists, Unitarians. And Lewes Prison once housed Eamon de Valera, after the Easter Rising.’

‘I did not know that,’ said Morley.

‘We don’t have a photograph, I’m afraid,’ said Michael. ‘But you’ll have heard perhaps of Reverend T.W. Horsfield, the historian?’ He pointed at an engraving of a man who looked very much like a Reverend T.W. Horsfield.

‘Ah yes, Horsfield, of course,’ said Morley.

‘And Gideon Mantell, the great Sussex geologist.’ He pointed at another engraving.

‘Discoverer of the bones of the iguanodon,’ said Morley. ‘Now him I do know about.’

‘Yes. Born in Lewes, and made his discoveries in Cuckfield. Many of his finds are now in the British Museum.’

‘How fascinating.’

‘Miriam, radical Sussex,’ said Morley. ‘Your sort of thing, eh?’

‘No women, I suppose?’ said Miriam.

‘I’m afraid not, no,’ said Michael.

‘Hmm,’ said Miriam, wandering off to sulk and enjoy her cigarette in peace.

‘So you’re here to write one of your county books, I understand,’ said Michael to Morley.

‘Yes, that’s correct. We are hoping to be able to travel across the county a little.’

‘Well, the greatest journey across Sussex, as you know, was that taken by Charles II in 1651, escaping with Thomas and George Gunter of Racton.’ Michael led us towards another green baize table, with another deadly dull display – this time of stuff vaguely relating to Charles II. ‘He first crossed the Broadhalfpenny Down, Catherington Down, Charlton Down, Idsworth Down, until reaching Compton Down, and then finally through Houghton Forest and so to Amberley and eventually to Brighton.’

‘Yes, an extraordinary journey,’ said Morley. ‘The definitive Sussex journey, one might say.’

‘Or one might not,’ said Miriam, who had wandered back, bored. ‘Depending on one’s point of view.’

Miriam looked at me and indicated that we should try to move things along.

‘Mr Anderson—’ I began.

‘Where else would you recommend we visit in the county, while we’re here?’ asked Morley.

Miriam shook her head at me in disgust.

‘Oh, there are so many wonderful places, and always new places to discover. I was visiting recently at a clergy house at Alfriston – I’d never been before – and which turned out to be a rare example of a fourteenth-century Wealden hall house.’

‘Really?’ said Miriam. ‘A fourteenth-century Wealden hall house?’

‘Yes, and the churches at—’

‘We don’t do churches,’ said Miriam firmly.

‘Well, Selmeston,’ said Michael, ‘pronounced by the locals Simson. That’s rather lovely. Firle, pronounced Furrel. Alciston, which is Ahlstone. The pronunciation takes a bit of getting used to, I’m afraid.’

‘Lewes almost sounds like Lose,’ said Morley.

‘I suppose it does,’ said Michael. ‘I’d never thought of that.’

‘And how do you find living in Lewes?’ asked Morley.

‘Oh, I adore it,’ said Michael. ‘I rather think of Lewes as like the nation in miniature, actually. You’ve got the Medieval alongside the Georgian alongside the Tudor alongside the—’

‘Knee bone connected to the thigh bone?’ said Miriam.

‘We’ve got the river and the racecourse, and it’s an assize town, of course. I think I like it because it seems … untainted.’

‘Really?’ said Miriam, her interest piqued. ‘Untainted in what sense, Mr Anderson?’

‘It’s a place where perhaps some of the problems and pressures brought by outsiders to the country have not reached.’

‘And the sorts of problems and pressures you have in mind are?’ asked Miriam.

‘Well, undesirables, really, you know, the Jews and their—’

One had begun to hear a certain amount of this sort of talk. One didn’t necessarily expect to hear it under the ancient tie-beams of the Barbican House in Lewes.

‘Oh dear,’ said Miriam, wagging her finger at Michael. ‘No, no, no. I didn’t realise you held such objectionable views, sir.’

‘Everyone is entitled to their opinion, miss, are they not?’

‘If their opinion is based on facts,’ said Miriam.

‘I think you’ll find if you look at what’s happening in London, miss—’

‘Do you know the play Sir Thomas More?’ asked Morley, who had been unusually silent for a moment, clearly gathering his thoughts.

‘I can’t say I do, sir—’

‘It’s about—’

‘Sir Thomas More?’ said Miriam.

‘Precisely,’ said Morley.

‘Relevance, Father?’

‘Bit of an Elizabethan obscurity, admittedly, but in the play – which I saw performed by students in London a few years ago, a really remarkable production—’

‘Anyway, Father.’

‘Anyway, in the play, More asks Londoners to imagine the plight of the “wretched strangers” – something like that – arriving with their children and their worldly goods at the port of London and he asks them – I’m paraphrasing here, obviously – what would you think, if you were the wretched stranger? To ignore the plight of the stranger, in More’s words, is to display “mountainish inhumanity”. It would not do for us English to be mountainish inhumane, would it?’

‘It rather depends, I think, Mr Morley, if one thinks that one does more good by encouraging people to come to this country, leaving behind their own culture and ways, or whether one might do better to encourage them to remain in their own countries and work for the good of their own people.’

‘And if the latter is not possible?’

‘Well, I’m afraid I’m an Englishman, Mr Morley, and for me, my nation and my people will always come first. Britain first.’

‘And last, with that sort of attitude,’ said Miriam.

A silence descended upon the great room of the ancient Sussex Archaeological Society, as the great irreconcilable differences between us became apparent.

Morley glanced up at one of the maps on the wall.

‘Regnum, I believe the Romans called it,’ he said, attempting to restart and redirect the conversation. Michael, in fairness, played along, through gritted teeth.

‘Chichester? Yes, Regnum, the great rural capital of England,’ he said.

‘And the southern terminal of Stane Street, I believe, which was one of the great ancient Roman roads, was it not?’

‘That’s right,’ said Michael.

‘The others being, Sefton?’

‘The other?’

‘Great Roman roads in Britain?’

‘Erm …’

‘Never mind. Romans. Anglo-Saxons. Vikings. Normans. Huguenots. Have all trod those roads, and doubtless made their homes here in Lewes, over many generations.’

‘All the more reason for us to protect the place now,’ said Michael.

‘Again, we shall have to agree to disagree,’ said Morley. He pointed to an area on the map.

‘Do you know, Mr Anderson, I’ve always wanted to have a look at Manhood,’ he said.

‘I think we’ve all wanted to have a look at manhood, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘Manhood, the name of the West Sussex peninsula,’ said Morley. ‘Just here.’

‘Lovely spot,’ said Michael.

‘Your West Sussex of course is never to be confused with your East Sussex.’

‘Certainly not,’ said Michael.

‘The West with its Chichester,’ said Morley, ‘its Crawley, its Horsham. The East with its Lewes, its Brighton and its Eastbourne. Anyway. Speaking of manhood.’ He was always liable to such unexpected swerves in conversation. ‘I hope you don’t mind if I ask you a personal question, Mr Anderson.’

‘A personal question?’

‘It’s just, with the terrible tragedy of the death of Lizzie Walter I wanted to check something. Someone mentioned that the two of you were …’

‘Engaged,’ said Miriam.

You will doubtless have heard before the expression that a person’s face ‘drained of colour’. Until one sees it for oneself, it’s hard to believe that a face can actually drain of colour, but that’s exactly what Michael Anderson’s face did at this point in our conversation.

‘Well,’ he said, his face drained. ‘Engaged? No. Well, I mean …’

‘Not engaged then?’ said Miriam.

‘We had been stepping out together for a while, but …’

‘Engaged or not engaged, then?’ said Miriam. ‘There’s a simple answer.’

‘We are – we were – very close,’ said Michael, choosing his words carefully and speaking slowly. ‘But we – drifted apart – recently.’ The colour had now not only returned to his face, he had started to turn a shade of puce that would have suited a spluttering colonel in a children’s comic.

‘Because?’ asked Miriam.

‘If you don’t mind my saying so, miss, I don’t think that’s any of your business,’ said Michael.

‘Perhaps the two of you disagreed on the future of fascism in this country, did you?’ said Miriam.

‘You’ve got a damned cheek, miss!’

‘That’s quite enough, Miriam, thank you,’ said Morley, first laying a hand upon her arm and then stepping towards Michael. ‘Apologies, Mr Anderson. I’m sure there was no intention to offend on my daughter’s part.’

‘It’s absolutely disgraceful,’ said Michael.

‘Now. Calm, please, Mr Anderson. Can I just ask—’

‘Can I just ask that you leave,’ said Michael, squaring up to Morley.

I stepped forward and between the two men, gently pushing them apart.

‘We are leaving, Mr Anderson,’ said Morley, perfectly calm. ‘But before we leave – we are dealing with a serious matter here – I wonder if you could tell me if you think you would recognise Lizzie’s handwriting, if you saw it?’

‘Again, I don’t think that’s any of your damned business,’ said Michael. ‘I have asked you to leave.’

‘We are simply doing our best to establish the facts of the matter,’ said Morley, ‘about Lizzie’s tragic death.’

‘I think you’ll find that’s the police’s job,’ said Michael. ‘Not some crowd of … outsiders.’

‘We are doing our best to assist the police,’ said Morley.

‘I’ll call them then, shall I, and they’ll confirm that?’

‘I am simply asking, Mr Anderson, if you think you would recognise Lizzie’s handwriting.’

‘Of course I would. We frequently corresponded.’

Morley produced the handwritten list of names.

‘And does this look like her handwriting?’

Michael looked at the list, looked at Miriam, looked at me.

‘No,’ he said. ‘Definitely not.’