KERNIS’S MILLENNIUM PRAYER that the twenty-first century, through its children, would usher in a “new era” of humanitarianism and peace shattered almost immediately after the century dawned in the devastating terrorism of 9/11. Aaron and Evelyne had just returned from California on the evening of September 10, 2001. Like many others around the country, they heard about the disaster after the first crash and watched on television as the other plane slammed into the second tower. From the George Washington Bridge, they could see the clouds of smoke downtown; the smell engulfed them as the wind blew north. That night they huddled with neighbors and a cousin visiting from Belgium.1

Although Kernis had previously written some of his most powerful compositions in reaction to war and devastation, this time he was “very certain” that he “could not and would not write music in direct response to the attack.” But after many months, he said, when the initial numbness had become “somewhat internalized, parts of the slow movement of my second string quartet suddenly re-sounded in my ears and expanded in sound and mass for a large … group.”2

It was two years before that expansion materialized, spurred by the efforts of Linda Hoeschler—to whom Kernis had dedicated the entire Second String Quartet. In 1990 Hoeschler had organized six couples into the “Minnesota Commissioning Club.” Each couple contributed $2,000 per year (later raised to $3,000) with the express purpose of commissioning new works. The club now gave its resources to Kernis to create an orchestral version of his “Sarabande Double, Sarabande Simple,” originally dedicated to the memory of arts supporter and friend Bette Snapp. Thus the quartet movement grew from a “private mourning for four instruments” and one individual into a public “sonic mass” for “far too many victims.”3 The Orchestra of St. Luke’s, conducted by Donald Runnicles, first performed Sarabanda in Memoriam on February 26, 2004, in a 9/11 memorial concert at Carnegie Hall. Runnicles programmed it along with Strauss’s Meta-morphosen (composed in 1945 as a memorial to the destruction of Dresden), Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Concerto funebre (“a lamentation against the 1938 Munich agreement that allowed Hitler to annex the Czech Sudentenland”), and Shostakovich’s Ninth Symphony. Poetry readings separated the musical works.

Perhaps in part to dispel those 2001 images of death—and with fatherhood on the horizon—Kernis composed two buoyant works the next year, the Concerto for Toy Piano and Orchestra, commissioned for Margaret Leng Tan, and the second Superstar Etude. The Toy Piano Concerto had its premiere in Singapore in January 2003 and its U.S. premiere in New York the following December (in a version for chamber ensemble). Kernis’s interest in this project stemmed not only from owning a toy piano as a child but also from his love of John Cage’s Suite for Toy Piano, which he calls “the essential ur-composition of the instrument.”4During the composition process, he also recalled Henry Cowell’s 1934 percussion octet Ostinato Pianissimo, in which eight ostinato figures of different lengths interact simultaneously.5 Kernis, who had used ostinato patterns as an organizing principle since his student days, based the opening movement on the model of the Indonesian gamelan. Throughout the five-minute movement a series of repeating motives freely overlap. He referenced gamelan music in other ways as well: a pseudo-pentatonic melody at the beginning, a texture evoking the polyphonic stratification of Indonesian music, the use of metallic percussion, and the ending stroke on the low gong. (In gamelan music, gong strokes mark the ends of major sections.) As usual, though, Kernis combined cultural influences. The slow movement is a gentle lullaby, and the finale introduces jazz and a whirling surface similar to those in some of his earlier works. He has since recast the concerto for standard grand piano with the title Three Flavors.

Superstar Etude no. 2 celebrates Thelonious Monk’s 1944 jazz standard “Round Midnight.” The Italian pianist Emanuele Arciuli commissioned it as one of twenty short pieces based on the same tune. He played all twenty in a concert at Columbia University on November 14, 2002. Kernis, in his version, made use of the principal five-note motive of “Round Midnight,” introducing it in various guises and clothing it in increasingly virtuosic attire. Arciuli characterizes the piece as “funny, crazily—even paradoxically—fast, humorous, and full of irony.”6 Indeed, the four-minute etude is a tour de force; it was, after all, influenced by, and written for, a “superstar.”7

If in the 1990s Kernis’s works had been stimulated, to a large degree, by public happenings (whether the opening of a new concert hall, urban riots, or wars past and present), those of the first decade of the twenty-first century drew primarily on private experiences, the most important being the birth of his twins and the death of his parents. Jonah David and Delphine Emalyah Kernis were born on February 23, 2003. (Both children now attend an advanced music school. Jonah plays the cello and Delphine plays the violin.) At the time of their birth, Aaron was in the midst of writing a choral work for the Dale Warland Singers, a three-movement composition, The Wheel of Time, the Dance, setting secular texts by Wendell Berry. The poems, says Kernis, celebrate the “dream of America’s heartland, an America concerned with good air, unpolluted food and water … a love and respect for nature.”8 They also deal with cycles of life, a topic that had attracted Kernis since his college years and now, in addition, reflected his new role as a father. On the private, personal plane, those new young lives helped combat the recurring images of the deaths of so many others.

Unfortunately, Mildred and Frank only enjoyed their grandchildren for one year before they too died. Mildred had developed recurring lymphoma, which subsided but then re-emerged in the form of uterine cancer. Frank, for his part, had not had an easy life after the family returned to Pennsylvania in 1970. When Aaron was in high school, Frank suffered a heart attack after slipping on the floor in a supermarket. The postal service assigned him to office work and then laid him off after determining that he couldn’t walk a full route. He found work in other areas (for example, in delicatessens and factories), but he had lost the job he loved. Then he suffered a second heart attack and required double bypass surgery, which “left him mentally and physically compromised,” says Kernis. By the time Mildred’s cancer returned, Frank was nearly eighty and was “getting a little far away.” During the final stages of Mildred’s illness, Aaron arranged for twenty-four-hour hospice care for her in the family home. Frank, at one point, stepped outside for the newspaper, neglecting to tie his shoes. He tripped on the concrete, hit his head, and never emerged from a vegetative state. Mildred died on March 26, 2004, at age seventy-seven; Frank passed away four months later, on July 7, at the age of eighty.

In addition to the personal events that stimulated Kernis’s change in direction during this period, he also instituted alterations to his working methods and his artistic representation. While he was composing Garden of Light, Kernis began to use the computer to help him sort through preliminary ideas. For previous works he had simply made “zillions of hand-written sketches.” Now he tried “writing hundreds of sketches on paper, and when I was happy with some, I would put them into the computer and start printing them out.” Using the Sibelius music engraving program with a MIDI interface, he could then listen to these ideas, “testing counterpoint or voice leading” in situations where he “couldn’t hold all the notes” in his head (or in his fingers). The ability to reproduce complex counterpoint immediately in sound was, of course, attractive, but Kernis found that the computer-generated output could also prove frustrating. “It’s utterly wrong when it comes to balance,” he notes. Thus, although the new technology was seductive, in some ways it made the compositional process more difficult by creating “an artificial orchestra that, once heard, had to be forgotten.” Nor did it reduce the volume of paper he generated. He would end up with piles of print-outs by the time a piece was finished.

The change in artistic representation also turned out to be less than successful. In January 2002 he signed an exclusive contract with Boosey and Hawkes. His motivation for leaving Schirmer at this point was to keep ownership of his copyrights. In this regard, Kernis cites the advice of Philip Glass, who served as a model and guide for many younger composers. Ultimately, however, Kernis was attracted by the Schirmer staff’s enthusiasm, knowledge, and support, and he soon returned to the firm. At the same time, however, he heeded Glass’s advice. In 2007 he established “AJK Music” and designated Schirmer as his exclusive representative and administrative agent.

When the twins were six months old Kernis began another orchestral work, Newly Drawn Sky, a seventeen-minute tone poem stimulated by a commission from the Ravinia Festival in honor of James Conlon’s first year as music director. Welz Kauffman, president of the festival, had been artistic administrator of the New York Philharmonic during the millennium symphonies project. He chose Kernis for the Ravinia commission, he says, because of “Aaron’s rigorous technical mastery, orchestration skills, and Romantic sensibility.”9 Kernis described the new work as “a lyrical, reflective piece for orchestra, a reminiscence of the first summer night by the ocean spent with my young twins … and of the changing colors of the summer sky at dusk.”

Newly Drawn Sky (2005) has a very different cast to it than Kernis’s previous works. There are no Jewish influences, nor any references to popular musics. Jazz—such a strong force in other recent works—is nearly absent. Even dance has a limited influence, and Kernis’s beloved mediant progressions are rare (although there is a lovely one near the end, at mm. 248–49). Kauffman’s faith in Kernis’s imaginative orchestration is well rewarded, but the individual virtuosity seen in many previous works is less in evidence here.

Despite the lack of some previous stylistic markers, Kernis’s individual voice—in the language he had come to find compelling—shines through clearly. The opening melody in the celli, for example, is formed from a rising scale with an upward leap at its end. In shape it resembles many others that had inspired him over the years, while paying tribute, in particular, to the beginning of the Symphony in Waves. And as in previous works, Kernis introduces this melody in an additive fashion: Two notes, G–A♭, then G–A♯, grow into a longer scalar line combining half and whole steps. The melody rises to the tritone C♮ and then exuberantly leaps up a fifth. This theme forms the basis for the opening and closing sections of the work, always evolving and transforming, taking on the different hues of the waning light of evening. Its reemergence near the end in two significant moments of arrival (mm. 163 and 198) gives an overall A B A' form to the piece.

With regard to harmony the work is also typically Kernisean. The guiding principle, presented at the outset, is a series of three-note, nontriadic chords in close harmony whose progression is governed by voice leading. As in previous works, Kernis uses cadential points to signal sectional divisions, although they come less frequently here than in other recent works (for instance, Garden of Light). At the same time, Kernis does not shy away from the grand gestures so apparent in other compositions. The orchestral sound is lush, and he gives vibrant solo passages to some of his favorite instruments: the trumpet, the English horn, the cellos, the violas, and the horns. And in typical fashion he frequently subdivides the violins to provide a dense texture. Contrapuntal elements predominate for most of the piece, but imitation (in contrast to his earlier works) is rare. The pervasive polyphonic texture makes the few moments of homorhythm stand out dramatically. One, in which almost the entire orchestra plays in unison, emerges starkly as a bold gesture. Another, near the end, features the opening theme in the winds and strings in hymn-like fashion. During this two-minute section the theme is underscored by rolls on tam-tams and cymbals that repeatedly swell and subside. The effect here, however, is nothing like that in the Second Symphony. Rather, it resembles the wash of metallic sounds at the end of Lament and Prayer. And like Lament as well, the end introduces a shimmering A major triad, over which the horns quietly articulate repeated chords based on A lydian. The final sonority mixes elements of A and E. This mixing of tonal and modal elements brings back images of the opening of the piece.

Overall, Newly Drawn Sky is a big, serious work, yet it is in no way sorrowful. Rather, the piece is grandiose and majestic, reflecting an awe of life on both the macro and the micro scale: the changing colors in the evening sky and the wonder of the new lives developing in Kernis’s private domain.

In five works from this period Kernis paid tribute to his parents: a ballad for cello solo and seven cellos (or recorded cellos, or piano, 2004), the third Superstar Etude for piano (2004, revised in 2007), Two Meditations for chorus and organ (2005–6), Two Movements (with Bells) for violin and piano (2007), and the Symphony of Meditations (Symphony no. 3, 2009). Mildred Kernis loved ballads, and Aaron had acknowledged her preference as early as 1993 in the third movement of 100 Greatest Dance Hits (“MOR Easy Listening Slow Dance Ballad”). Now, reflecting on her life, he explored the style at greater length, both in the cello piece and in Superstar Etude no. 3, which is titled Ballad(e) Out of the Blues (a live recording by Mihaela Ursuleasa is included on the book’s Web site).10 At ten minutes, it is the longest of the three superstar piano etudes, and it is also the most technically difficult. (To a great extent it is a study for the left hand.) Compared to Newly Drawn Sky, Superstar Etude no. 3 shows much greater affinity with previous works. There are overt references to popular musics (in this case blues) and to Debussy, Messiaen, Ives, and Gershwin. Strong tonal elements devolve into dissonance. Here, as elsewhere, Kernis looks at color, exploiting the many hues possible on the piano.

After a short introduction, Kernis brings in his blues melody, complete with ninth chords and other characteristic jazz harmonies. Over it he lays virtuosic improvisatory-sounding passagework that creates a filigree winding over the tune. Although the harmonies reference the musics of black Americans (at one point he gives the instruction “with a gospel feel”), Kernis casts these iconic models in his own idiosyncratic language. He directly evokes Gershwin in the central section with hints of the piano preludes, Porgy and Bess, and Rhapsody in Blue. After a buildup to extreme dissonance, the piano imitates a harp (Kernis imagined an “Ivesian haze” here), and then the influence of Gershwin reappears for one more fleeting moment. The most unusual effect, however, comes during the last minute of the piece. Here Kernis uses the piano’s lowest range to create a growling sound akin to the percussion parts in many of his orchestral works. The similarity to rolls on metal percussion instruments is enhanced by his instruction that this section be “heavily pedaled, somewhat blurry.” Beginning pianissimo, the rumbling low scales build dynamically to ffff, much like the effect he called for on the tam-tams and cymbals in the Symphony in Waves, the Second Symphony, and other works. The piece ends, however, not with this crescendo, but with two shimmering tremolos and a long held note (a typical feature of jazz improvisations on standard tunes), followed by a quick afterthought: the pianist, with the una corda pedal depressed, rushes “subito presto” down to the bottom of the keyboard.

The year after he completed the third Superstar Etude, Kernis composed Two Meditations for choir and organ. The occasion was historic—the rededication of an organ at the Plum Street Temple in Cincinnati—and the commission came from the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, through its Tangeman Sacred Music Center. The Vocal Arts Ensemble, a long-running professional chamber choir in the city, performed the premiere on April 1, 2006. The Plum Street Temple has a long and illustrious history in the evolution of Reform Judaism in the United States. Its grandiose building was dedicated in 1866 as the place of worship for the Lodge Street Synagogue, which dates its founding back to 1840. In 1853 the congregation arranged to hire as its rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise (1819–1900), who is now widely recognized as one of the most influential leaders in the U.S. Reform movement. Wise was instrumental in the founding of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations—an umbrella organization for U.S. Reform synagogues that was established in 1873—and Hebrew Union College, which opened its doors two years later. (The college is still the Reform movement’s seminary, but now also has branches in New York and Los Angeles). From the start of his tenure in Cincinnati, Wise was concerned about synagogue music. He introduced a choir in 1854 (directing it with his violin) and the following year began advocating for installation of an organ.11 Choirs and organs are not part of traditional Jewish worship; in fact, musical instruments are proscribed in Orthodox practice. Early nineteenth-century German-Jewish reforms, however, reinstated the use of instruments,12 and a choral music tradition began to take hold first in Germany and Austria, and then elsewhere. In a very real sense, these reforms—including buildings such as the Plum Street Temple—imitated Protestant practices and were designed to bring Judaic rituals into conformity with modern religious worship in the Christian world. The Plum Street building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places by the Department of the Interior in 1975. The rededication of its organ capped a wholesale reconstruction of the building and was thus a major event in the life of the congregation.

For texts, Kernis turned once again to Stephen Mitchell, whose Enlightened Heart had inspired Simple Songs in 1991. This time he selected two of Mitchell’s psalm adaptations, contained in a volume of fifty psalms from the Hebrew Bible.13 As in the Enlightened Heart, Mitchell’s poems are not translations but, rather, interpretations. He noted in his preface that he “paraphrased, expanded, contracted, deleted, shuffled the order of verses, and freely improvised on the themes of the originals.” Responding to the deaths of his parents, Kernis chose two psalms that “speak to the acceptance of death and the loving presence of God.” In Psalm 39, the poet notes the transience of life. Mitchell freely renders verses 5–6 as “All of us flash into being, / as insubstantial as breath. / Our lives are a fleeting shadow; / then we vanish into the night.” The second (Psalm 84) concerns the journey to “the place of perfect repose.”

Kernis set both psalms for choir either a cappella or with organ accompaniment. In the first one he applied his practice of moving between tonal or consonant and atonal or dissonant language to individual phrases rather than to the piece as a whole. Numerous phrases begin and end on unisons, triads, or thirds but become dissonant at their midpoints. The movement overall is slow and meditative, with the organ version containing a striking a cappella section near the end.

In the second piece the consonant-dissonant dichotomy plays out on the level of the overall structure. (Again the influences of Messiaen and Pärt are apparent.) It begins and ends with strong tonal statements in D♭ major but becomes highly dissonant at the movement’s center. Also making this movement difficult for the singers are the extended a cappella sections. The texture consists of an alternation between unaccompanied and accompanied sections, requiring excellent choral intonation. In both works Kernis periodically subdivides the choir into as many as eight parts. The writing here, both in style and musical language, anticipates that of the third symphony, which he would begin the following year.

The year 2006 proved extremely productive for Kernis. Not only did he complete the Two Meditations for Cincinnati, but he also wrote a twenty-minute chamber ensemble piece for the San Francisco Conservatory and received a commission for a violin and piano duo from the BBC Proms. The former honored the inauguration of a new dynamic facility in the heart of San Francisco, around the corner from the city’s major performing arts venues. The San Francisco Conservatory had been incorporated in 1923 as an outgrowth of a piano school founded by Ada Clement in 1917, and, since the 1950s, it had been located in the western part of town near Golden Gate Park. Long an artistic bulwark of the city, the conservatory now moved front and center geographically as well. To honor the opening of the facility’s new concert hall, the school turned to its former student Aaron Jay Kernis to compose a new work. The commission was funded by the Fleishhacker Foundation, established by a family with a long history of support for the arts in San Francisco. Banker brothers Herbert and Mortimer Fleishhacker had been among the initial two hundred founders of the San Francisco Symphony in 1911, and Herbert had worked tirelessly to bring about the construction of War Memorial Opera House. (He was part of a two-decade-long political fight to replace an auditorium destroyed in the devastating fires of 1906; the opera house finally opened in 1932.)14

Two Awakenings and a Double Lullaby, for soprano, violin, guitar, and piano (2006),15 honors Kernis’s twins. The first movement’s text, by the English poet Thomas Traherne (1636–74), celebrates in metaphysical language the wonder of the birth of a baby boy. The setting begins and ends quietly (and tonally, in A) with bell sounds but rises in the center to impassioned excitement. For the second movement Kernis again turned to Carol Ann Duffy, author of the texts of Valentines. “The Light Gatherer” centers on the poet’s wonder concerning her young daughter. This movement, in contrast to the first, is lively, energetic, sparkling, and agile. It exudes an exuberance evoking running, playing, swinging, and dancing. For the third movement Kernis chose two texts about angels, recalling, perhaps, the slow movement of his first quartet (musica celestis). Englebert Humperdinck’s famous “When at night I go to sleep” talks of fourteen angels in seven pairs: two at the head, two at the feet, two on the right, two on the left, two warmly covering, two hovering above, and two guiding “my steps to heaven.” The emphasis on the number two clearly references the twins, and the setting at first intertwines violin and soprano in an extended duet. (The piano accompanies this section but plays a role subsidiary to the two treble lines; the guitar does not enter until the last two minutes of the movement.) The second text used in this movement, from an American spiritual, contains the phrase “angels watching over me.” This movement, arguably the highlight of the set, is thus a double lullaby. It begins with a gentle hymn, features in the middle one of Kernis’s favorite mediant progressions taking us to E (the key with which he will also end his third symphony), and eventually winds its way back to the A where the entire work began, as the soprano sings “two, two, two.”

The commission Kernis received in 2006 came from the BBC Promenade Concerts (familiarly known as the Proms), London’s renowned eight-week series of daily concerts, most of which are held in the 5,500-seat Royal Albert Hall. The previous year the Proms had begun to offer a series of chamber music performances as well, held in the more modest Cadogan Hall; for this series the BBC commissioned Kernis to write a piece for violin and piano. The renowned Canadian violinist James Ehnes performed Two Movements (with Bells) with pianist Eduard Laurel on July 23, 2007. Kernis dedicated the seventeen-minute piece to his father, whose “favorite music was jazz and American popular song of the 40’s and 50’s.”16 His program notes state that he was surprised to see how strongly the influence of improvisation in jazz, blues, and ballad singing had emerged in recent years, and he traced the thread back to New Era Dance with its evocations of big band jazz. But Two Movements (with Bells) is very different in character from New Era Dance. It is largely introspective but is interrupted by sections of “restless, often uneasy lines and silences” and wild “outbursts of activity.” In the first movement Kernis evokes bell sounds in the piano part, first underlying leggiero skittering motives in the violin and then broadly dominating the texture in the movement’s extended coda. Bells had figured in earlier works such as the opening of Before Sleep and Dreams, the second movement of the Second Symphony, and, most prominent, the end of Still Movement with Hymn. Furthermore, the overall lamenting character of the piece brings to mind Kernis’s history of works about death. Here, however, there is sadness but none of the anger or bitterness of these earlier works. Frank’s death, though painful, was not unexpected, not the result of violence, not untimely in the broad scheme of life. Indeed, Kernis refuses to link the bell sounds specifically to death. “Are they funeral bells,” he asks in his notes, “bells of distant memory, bells made of dense clusters of overtones which fracture and fragment from the intensity of their physical attack?”

Kernis notes that the first movement of this work is “a free interpretation of sonata form in five sections: slow opening with intensification, an active and improvisatory middle, a return of pensive slow music, a shortened section of faster music, and a calming coda.” In the second movement he provides variations on an original jazzy ballad-like tune.

There is no room for improvisation in the performance of this piece, yet many sections give the impression of written-out extemporizations; they were stimulated, Kernis notes, by the “improvisatory impetuousness” of free jazz. If the bell sounds and lamenting characterization recall earlier pieces, the harmonic language here is more akin to that of recent works such as Newly Drawn Sky. Although this language is, overall, more chromatic and consistently dissonant than that of his earlier pieces, Kernis retains from the past his practice of moving from consonance to dissonance and back to consonance within each movement.

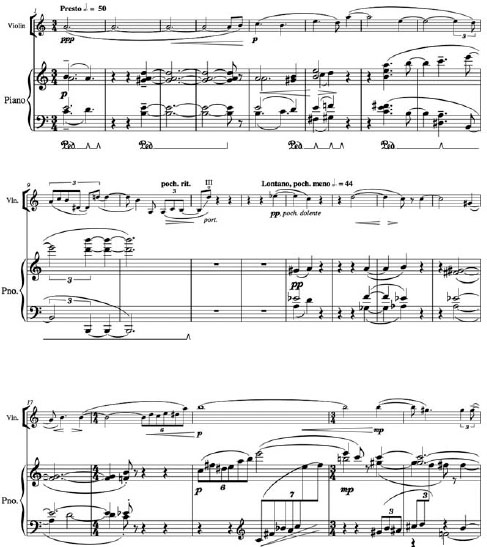

The use of variations on a small motive again forms a theme through the work. In this case that motive consists of three notes. The first two form a sigh motive such as that found in many Baroque works; the third is a long note that usually enters after an intervening rest (see figure 13a, mm. 1–4 and 13–17 in the piano and 12–14 in the violin). The sigh recurs intermittently throughout the piece, making its final appearance at the very end of the second movement. (In figure 13b, note that the sigh appears four times in the piano in mm. 89–91.) Then a gentle cluster in the piano introduces rising lines filled with fourths in both instruments and ending with prominent G♮s and C♮s and a soft piano bell.

Figure 13. Two Movements (with Bells), 2007. (Copyright © 2007 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.)

a. beginning

b. ending

In August 2007 Kernis began work on his third and longest symphony: the Symphony of Meditations for chorus and orchestra. For this piece he assembled a lengthy text from the work of the eleventh-century Sephardic philosopher and poet Solomon Ibn Gabirol (ca. 1021–ca. 1058), using translations by Peter Cole. (The text of the symphony is in English except for a few lines in Hebrew near the end.) The composition process ended up consuming nearly two years; the Seattle Symphony and chorus, conducted by Gerard Schwarz, presented the premiere on June 25, 2009. Kernis dedicated the symphony to Jeff and Lara Sanderson (the commissioners) “in profound appreciation of their support and belief in the transformative power of music,” to Schwarz and his wife Jody, and to his own parents.

Kernis’s third symphony forms a logical extension of (and in some ways an ending to) the direction in which he had been moving for years. Meditative themes had increasingly attracted his attention, from the prayers that concluded Still Movement with Hymn and Lament and Prayer through the universalist spirituality in Garden of Light and Two Movements (with Bells). As we have seen, medieval texts, from Hildegard von Bingen to Mechthild of Magdeburg, had often been the vehicles for these meditations, speaking to Kernis in mystical images that stimulated his musical expression, both vocal and instrumental. But in the words of Ibn Gabirol, Kernis found this medieval mysticism not in the Christian tradition but, rather, in his own. Judaic themes, of course, had motivated him as early as 1981, inspired by Jewish history (especially the Holocaust) and ritual practice (cantorial vocal styles and congregational heterophony). Now this heritage took on a new dimension, for Ibn Gabirol imbued his poetry with neo-Platonist philosophy: the existence, if not the essence, of God can be known, he argues, and the universe, from the divine soul to the material world, is a unity. Kernis emphasized this theme through a cyclical return throughout the symphony to the words “God is One.”

The Third Symphony also builds on Kernis’s attraction to narrative and his unfulfilled desire to write an opera. He constructed his own story line by choosing and intermingling excerpts from thirteen of Ibn Gabirol’s texts: four independent poems and nine sections of the poet’s major work, Keter Malkhut (Kingdom’s Crown).

When the Chicago Symphony had proposed a commission for a choral symphony back in 1995, Kernis was not ready to write one (see Chapter 6). Now, however, after the birth of his children and the death of his parents—and especially after discovering Cole’s work—the task became for him a fundamental necessity. The Seattle Symphony’s request for a large composition provided the opportunity to fill that need.

In many respects Ibn Gabirol’s themes were foreign to Kernis: praise of and supplication to God; preparation for death and a belief in the afterlife; sin and the seeking of divine mercy. But at the same time he found it “compelling and nurturing to embrace these words … while attempting to grapple honestly with their content…. In crucial ways,” he wrote, “this piece represents to me a statement of my faith and has made me ruminate … upon how it is that we human beings and our souls are created and shaped.”17

Kernis and Cole had met in the early 1990s through a mutual friend. At the time, Cole was guest-editing a volume of Conjunctions and invited Kernis to conduct the interview with John Adams quoted in Chapter 2. When Aaron and Evelyne traveled to Jerusalem in 1997 in order for Aaron to judge the (now defunct) Bernstein competition, Cole acted as their guide. He also showed Kernis the text of Kingdom’s Crown, which he was translating. Kernis was stunned. The poem was “magnificent … symphonic in scope and proportion,” he thought.18

Cole’s collection of translations appeared in print four years later. It contains not only Kingdom’s Crown but also some of Ibn Gabirol’s independent shorter poems.19 Following the death of his parents, Kernis reread Cole’s collection and was strongly moved by it. The symphony “started out to be about twenty minutes,” recalls Gerard Schwarz, “and Aaron said he wanted to use a text. I said, ‘Fine.’ Then he said he’d like to use a sixteen-voice professional choir from Canada … and of course I said, ‘Fine.’ Then he said he’d like to amplify the choir so that he could write freely for the orchestra. I was less enthusiastic about that.”20 The Symphony of Meditations turned out to be sixty-eight minutes long and requires a large (and skilled) chorus along with three soloists. (The small Canadian chorus “was fabulous,” Kernis recalls, but it would not have worked with the massive orchestral forces he ultimately used.) Because the Seattle Symphony Chorus was not on board in 2007–8, Schwarz postponed the premiere until 2009.

As shown in table 6, Kernis pieced together the text by cutting and pasting elements from various parts of Cole’s book. (Cole was supportive of this process and made himself available for extensive consultation about the background of, and symbolism in, the poetry.) Despite the symphony’s narrative structure, Kernis did not assemble the lyrics in the order of the original, nor did he select all parts of the text before he began composing the music. He was first drawn to the words that form the central part of the second movement, which consist of a series of four-line stanzas preceded and followed by this three-line refrain:21

All the creatures of earth and heaven

together as one bear witness in saying:

the Lord is One and One is his name.

The final line of this refrain not only reflects Ibn Gabirol’s postulate concerning the unity of God but also refers quite directly to the Shema, a central prayer in the Jewish service, often referred to as the “watchword” of the faith: “Shema Yisrael, Adonai elohenu, Adonai echad” (Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One). This text proclaiming God’s oneness creates a unity in Kernis’s symphony as well. He incorporates versions of it in movement 1 at the end of the central choral section, in the middle part of movement 2 as the refrain for each stanza, and in the final moments of the forty-six-minute finale (in this case, in the Hebrew original: “Adonai echad,” God is One).

TABLE 6. Symphony of Meditations (Symphony no. 3): movements, text sources, and scoring

* This column provides page numbers in the source text: Selected Poems of Solomon Ibn Gabirol, translated from the Hebrew by Peter Cole (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001).

Kernis composed the second movement first and then the finale (whose texts are drawn exclusively from Kingdom’s Crown) before he selected the poetry for the opening movement whose text puts the emphasis on the speaker: “I look for you early”; “I come confused / and afraid”; “I seek you every evening and dawn”; “I’ll praise the name of the Lord.” Reflecting Ibn Gabirol’s philosophy, Kernis structured his symphony to progress from the individual’s relation to the divine in movement 1 to three manifestations of God (sky, earth, and heart) and the oneness of nature in movement 2 to divine mercy in movement 3.

In addition to the Shema paraphrase, other poems that Kernis selected—in particular, those from Kingdom’s Crown (KC)—contain references to the Jewish liturgy. Several of the texts in the finale will immediately remind modern Jews of prayers found in the service for Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. On this fast day congregants reflect on the previous year, acknowledging their individual failings, and vow to improve themselves in the year to come. The traditional prayers evoke divine judgment through the metaphor of a book in which names are inscribed for the coming year as destined for good or for ill. Although one’s fate can be altered through repentance and meritorious deeds, at the end of the atonement day the gates of mercy symbolically close, sealing the future. (The balance between predestination and free will in this context has absorbed biblical scholars’ attention for centuries.) Cole’s translation of KC XXXVII reads, in part, “For what is man that you’d judge him, / but haunted vanity and breath pursued.” This text brings to mind the fifth verse of Psalm 5, traditionally read on Yom Kippur: “What is man, that Thou art mindful of him? / And the son of man, that Thou thinkest of him?” A hint of the twenty-third psalm appears in KC XXXIX, and a direct reference to the liturgy comes in KC XXXIV, whose text closely resembles the “Ashamnu” confessional prayer, traditionally recited ten times during the Yom Kippur services. During the public recitations of this prayer, the congregation rises as a body and confesses to a list of twenty-four sins: “We have trespassed; we have dealt treacherously; we have robbed; we have spoken slander; we have acted perversely; we have done wrong; we have acted presumptuously; we have done violence; we have practiced deceit; we have counseled evil; we have spoken falsehood; we have scoffed; we have revolted; we have blasphemed; we have rebelled; we have committed iniquity; we have transgressed; we have oppressed; we have been stiff-necked; we have acted wickedly; we have dealt corruptly; we have committed abomination; we have gone astray; we have led others astray.” The communal confession recognizes society’s common culpability for all transgressive acts and allows individual confession without public embarrassment. Compare the text of KC XXXIV, which reads in part: “and too often I’ve uttered blasphemy— / and been perverse and lawless; / fractious and full of violence; / I’ve lied and counseled evil—deceived, scoffed and rebelled; // been scornful, perverse and intransigent, / stubborn, harsh and senseless; / I’ve cut off your reproach and been cruel. / I’ve committed abominable acts / and wandered far from my path.” The wording of the Ashamnu prayer as we know it today was already in use several centuries before Ibn Gabirol wrote Keter Malkhut; indeed, here and elsewhere he was in effect glossing on material that would have been familiar to his readers.22

The right-hand column in table 6 shows that movements 1 and 2 have a similar musical and textual structure. Each has a tripartite form, beginning with a section for soloist and orchestra, followed by a choral section, and finally by an altered return that combines soloist with chorus and uses texts already sung in sections 1 and 2. The first movement, though the shortest of the three, is imposing in style, dynamics, and emotional affect. If it could be compared to anything that Kernis previously created, it might be the music evoking huge stone tablets that begins the finale of Colored Field. That movement opens with a stark rising melodic second. Here, too, the rising step figures prominently, marking the end of each of the three sections. The opening section for baritone ends with a dramatic arrival on E (m. 35), which Kernis transforms, in a transcendent moment, into a B major triad via the soloist’s step up to the dominant F♮. The choral section that follows concludes with another climactic arrival, on the words “You are One.” Kernis leads into this outburst with a chromatic unison ascent from E to B♭ and then, on the repetition of the text, the B♭ rises to a C major chord, historically a key symbolizing triumph. A grand pause greets this exclamation. The concluding section ends with two rising seconds in long notes in the solo part: C♮–D♮–E♮. The last two notes are sung over an iridescent C♮ major chord in the orchestra.

As in his previous works, Kernis moves back and forth between diatonic and chromatic language. The opening motive in the baritone part centers on A, but by measure 6 it has already shifted to A♭. This opening melody is for the most part angular and disjunct, with prominent descending and ascending leaps of fourths and fifths that convey strength and solidity. At the chorus’s entry in m. 36, the unison melody is identical to the opening but now transposed a step higher. The third section opens with the contrabasses playing a version of the same theme on F♮, now, however, with a soft and subdued character.

In shape this movement thus forms an arch with a double climax in the middle, at the start and the end of the choral section. The second climax emphasizes the symphony’s idée fixe through the twofold repetition of “You are One.” The trajectory of most of the melodic lines is upward, the overall affect suggesting the majesty of God and human arms lifted in praise.

The second movement can stand on its own as a separate piece; Kernis has authorized its independent performance. (The live performance by the Yale Philharmonia and choral ensembles, conducted by Kernis, appears on this book’s Web site.) In contrast to the first movement, it begins introspectively with the high strings divided into seven parts followed by a plaintive melody in the oboe. After the succeeding soprano solo section, the instrumental elements return in reverse order: first the oboe, then the strings. The highlight of the movement, however, is the central choral section, “All the creatures of earth,” which is dance-like and exuberant, centered strongly in B♭ (a mediant relationship to the movement’s opening in F♮). Each time the refrain text appears, its musical setting becomes more ecstatic. In the final rendition, Kernis repeats the last line, “the Lord is One,” forty-four times using jazzy changing meters and a homorhythmic texture in the voices that renders the words clear and the style declamatory. The surrounding orchestral texture becomes increasingly thick and excited, reaching a climactic moment with the piano, strings, and woodwinds in a kind of varied ostinato in repeated notes while the brass and percussion underscore the choral parts. The whole section comes to a crashing arrival on B♭ for the final words of the text: “and One is his name.” The bass instruments and chorus then repeat this pitch in long notes for another twenty-one measures, grounding fragmentary melodic motives in the rest of the orchestra. Then the B♭ continues in the chorus, winding down over the course of another nineteen bars to introduce the tranquil final section for soprano and chorus.

The finale is essentially a forty-six-minute cantata for baritone, soprano, and chorus (with a brief passage for solo tenor) divided into two large sections of nearly equal length, separated by an instrumental interlude. (Kernis envisioned this movement as a gigantic symphonic form.) The narrative structure recounts the journey of the individual from shame and guilt in the first section to redemption through repentance and faith in the second.

The first half of the movement is itself subdivided into two discrete sections, each of which has a tripartite structure. In the first of them (1a), the three parts are defined by their vocal scoring: a section for baritone solo, a choral interlude, and a return of the soloist. The movement opens with a sixteen-measure melody in the unaccompanied solo timpani. The timpanist executes fourteen different pitches by retuning the drums during the course of playing them. Although this highly challenging technique has been used by other twentieth-century composers, the foregrounding of the timpani in such a central and exposed role is highly unusual. Its melody features minor thirds and a series of tritones—an interval that historically has stood as the symbol of sin. The baritone solo section that follows rises to a climax on the words “you are One” (repeated Cs in the voice) and “you are the Lord my God” (a rising third and then a tritone). Kernis juxtaposes the light of the third with the darkness of the tritone to suggest uncertainty and doubt, as the speaker laments his weakness and his shame at his own failings. The choral section reinforces this negative self-image (here Kernis extracts individual words and phrases from Cole’s text: “dust … vessel … shame…. a spider’s poison; a lying heart”), ushering in a slow and introspective solo section with the singer accompanied by harp, piccolo, and soft, sustained strings.

In the next part (section 1b), the three-part structure is defined not only by scoring but also by melodic character. Two arias for baritone surround a central section that is primarily for chorus. Preceding both arias are instrumental passages featuring the cello. In the first case, the cello’s line is cantorial, with recitative-like melodic motion and repeated notes in the style of a chant. The first aria is gentle, as the singer appeals to God to allow repentance and spiritual transformation before death: “for if I depart from the world as I entered, / and naked and empty return as I came, / why was I made— / or called to bear witness to struggle and pain?” The soloist’s line begins with a minor third, recollecting the opening motive of the movement in the timpani, but now the tritones have disappeared, replaced by the solidity of rising and falling fifths. The second aria evokes Bach, in part owing to its A B A' form, typical for Baroque arias. It opens with a rising fifth, recalling the first aria’s melody. The B section introduces the Ashamnu confessional—the frightful admission of human frailty and failure—underscored by angry outbursts in the orchestra. Then the melody of the A section returns, its pleading fifths accompanied again by the cello, but now in such a high register that it almost sounds like a violin. That Kernis chose to use the high cello rather than a violin has both aural and symbolic implications. The musical effect creates a rise from a “natural” human plane to an elevated transfiguration, as the cellist literally reaches up the fingerboard to the instrument’s highest notes. “My God,” sings the soloist, “What am I or my life? / What is my might and my righteousness? / Throughout the days of my being I’m nothing / and what then after I die?” The choral section that separates the two arias focuses on the compassion of God and the ability of humans to alter their behavior. A lovely a cappella setting accompanies the text “How much trouble my eyes / have overlooked as you helped me,” and the music builds to a fortissimo outburst in an evocation of the day of judgment. Here Kernis condenses Cole’s translation considerably, eliminating in the process Ibn Gabirol’s original balance between mercy and anger. Kernis retains only the latter. Cole’s original—”Judge me, Lord, by the standard of mercy, / and not in your anger, / unless you’d bring me to nothing”—becomes in the symphony the far harsher “Judge me not, Lord, / not in your anger, / unless you’d bring me to nothing.” Befitting this fearful vision, the section ends with a persistent hammering on E♭ for six fortissimo measures before its energy dissipates to usher in the second aria.

If the first half the movement is filled with self-recrimination, the second half focuses on praise of the divine and the unity of the world. It begins with an a cappella choral prayer (section 2a): open my heart to repentance; protect and shelter me with mercy. The soprano soloist then appeals, at first with the women of the choir and then alone, for the power to see good in the world and to take pleasure in creation (a reflection of Kernis’s personal worldview, articulated in many previous compositions). Section 2b ends with a duet between the solo soprano and the flute leading into a decorative, effusive flute cadenza. (The flute-soprano duet in Garden of Light comes to mind.) The baritone then reenters in humility (2c), but eventually rises to a tonal, melodious exclamation: “Bring me to peace,” which the chorus takes up as the soloist yearns to be placed “among the righteous” after death.

The final part of the movement (section 2d) extols and glorifies God. The chorus breaks into Hebrew at the end of this paean of praise, and then the baritone reenters singing a paraphrase of Psalm 19:15: “May the words of my mouth and my heart’s meditation / before you be pleasing— / my rock— / and my redemption.” These words are nearly identical to those of the “Yih’yu l’ratzon” (“May the words of my mouth”), traditionally recited at the end of the Amida, the central part of the Jewish Sabbath and High Holy Day services. The Yih’yu expresses the hope that the supplications just offered will prove acceptable to God. In Kernis’s symphony, the baritone sings the Yih’yu paraphrase to a stately melody filled with upward leaps of fourths and fifths while the choir chants “Adonai elohenu, Adonai echad” (“The Lord our God, the Lord is One”—the Shema paraphrase) in unison on repeated Es. These repeated notes persist continuously for the final two minutes of the symphony, gradually joined by the instrumental forces and the soloist, who ascends from B to E, sliding between pitches to lend a Semitic inflection to the melodic line. The music builds in density and volume to a triumphant ending on the open fifth E–B (see figure 14).

Given Kernis’s upbringing as a cultural Jew—with a spiritual link to his heritage but without its ritualistic trimmings—the Third Symphony begs the question of his own religious beliefs. It is not a matter for which he has a clear answer. “By no means have I been able to integrate my love for spiritual texts and feelings of inner spiritual experience with rationalism and believing only in what one observes empirically,” he says. “They simply exist side by side; so when my children ask me if I believe in God, I either answer that I believe in people’s desire to have belief in what they feel but cannot explain, or say that sometimes I do believe in God, and feel that the Divine is a source of energy of all things, a life-force that all beings and nature draw upon.”23

Figure 14. Symphony of Meditations (Symphony no. 3), 2009, end. (Copyright © 2009 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.)

In the same year in which the Third Symphony was performed (first in Seattle and then at Yale), Kernis completed two concerti: Concerto with Echoes for chamber orchestra and a voice, a messenger for trumpet solo and wind ensemble (dedicated to the memory of his cousin Michael Kernis, 1955–2009). The first work was commissioned by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra as part of its New Brandenburg Project, the second by the New York Philharmonic and the Big 10 Band Association for Philip Smith, principal trumpeter of the Philharmonic. The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra performed Concerto with Echoes on October 8, 2009, only a month before the second performance of the Third Symphony at Yale, but the trumpet concerto was not performed until April 2, 2013. The Philharmonic had programmed it for December 28–30, 2010, but unfortunately Mother Nature intervened to cause a cancellation—a very rare occurrence in the annals of Philharmonic concerts. The orchestra members had had the previous week off, and so a double rehearsal was scheduled on December 27. But on the 26th a massive blizzard hit the area and players were stranded. Kernis’s concerto was canceled, as was a performance of Christopher Rouse’s oboe concerto and Hindemith’s horn concerto. In their place, the audience heard familiar selections by Sibelius, Debussy, and Tchaikovsky.24

If the Third Symphony is lavish in terms of length and performance forces, paying tribute to Kernis’s Jewish roots, the Concerto with Echoes is quite the opposite: a rather succinct (seventeen-minute) instrumental work for chamber orchestra with no Jewish references, projecting instead his admiration for the German Baroque. The work was inspired directly by Bach’s sixth Brandenburg concerto, which calls for violas, violas da gamba, cellos, bass, and harpsichord, and indirectly by the keyboard toccatas, the C minor passacaglia, and the first ricercar from the Musical Offering (in reality a three-voiced fugue). As in the sixth Brandenburg, Kernis uses violas, cellos, and basses, but no violins. In the second and third movements, he introduces pairs of oboes, horns, and bassoons, as well as a single trumpet and a few percussion instruments such as vibraphone and tuned gongs.

The first movement begins quietly with “two spiraling solo violas [and then two cellos], like identical twins following each other breathlessly through a hall of mirrors.”25 This introduction leads into an extroverted toccata—designated as such in the score. It bears a distinct resemblance to the ritornello form characteristic of the Baroque concerto grosso. A virtuosic tutti theme characterized by fast sixteenth notes, repeated pitches, and contrapuntal interplay alternates with somewhat quieter sections scored for soloists. The three-minute movement is a breathless showpiece for the orchestra, which is divided into anywhere from four to nine separate lines.

The slow second movement is a passacaglia in eleven sections. Its principal four-note theme is introduced by the first violas in the opening nine-measure section. Ten variations follow, which vary in length from four to fourteen measures and, typically, move further from the original theme as the movement progresses. The final section—as in previous works by Kernis but also as in variation sets from Haydn to Brahms—returns to a simple but altered version of the opening. Within the variations Kernis uses procedures typical of Baroque music, for example, thematic augmentation in the fourth and eighth sections and partial diminution in the ninth. Mood and texture vary greatly, from the gentle fourth section, which features long notes and a theme in the oboe, to the fast, nearly homorhythmic sixth section, to a grave mood in the seventh, which highlights chimes and trumpet. The savage tenth section contrasts strongly with the quiet meditative return to the theme in the last variation. The movement ends with a tender mediant progression, the final shimmering C major chord embellished with rising fifths in the horns.

The concerto concludes with an aria marked “dolente, grazioso” in 6/8. It is, in fact, like a Baroque siciliano, which is often compared to a lilting cradle song. The second oboist changes to English horn, lending a more subdued tone to the work, but overall the spirit is graceful and even, at times, pastoral. The texture, as usual with Kernis, is contrapuntal and intricate but at the same time features a clarity that makes the movement comprehensible even to novice listeners. The work comes to a conclusion in the very depths of the string range, with the melodic movement in the double basses reaching down to a low D.

In contrast to Concerto with Echoes, the trumpet concerto draws deeply on Kernis’s Jewish heritage, particularly in the finale, whose inspiration was the shofar, a ram’s horn blown on Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year). The blowing of the shofar recalls a ritual practice from the biblical era. The instrument sounds with trumpet-like blasts to herald the coming year and to call urgently on congregants to turn their thoughts to righteous deeds in the future. (Smith, when he asked Kernis to write the concerto, had suggested using the trumpet-like instruments mentioned in scripture as an inspiration.) During the service for Rosh Hashanah and at the end of the Yom Kippur fast, the shofar is sounded publicly, articulating three motives, each of which is preceded by a verbal call by the rabbi or cantor: “tekiah,” answered by a rising fifth (or fourth, depending on the instrument), “shevarim,” followed the same interval sounded three times in a row, and “teruah,” answered by eight repeated notes.26 Kernis titled the finale of his four-movement concerto “Monument—Tekiah Teruah,” and he uses a rising fourth and repeated-note figures as motivic elements.

The first and third movements have a less direct relation to Kernis’s faith, although Jewish elements were always in the back of his mind. “The mood of these movements contains much typically Jewish soul-searching,” he notes. The first is “Morning Prayer,” the third “Night Prayer.” Both are slow. Between them is the lively “Timbrel Psalm.” The timbrel is the biblical precursor to the tambourine. Here Kernis directly references the 150th psalm, a text used by numerous composers because it urges praise of God through music. “Praise God with the blast of the shofar,” writes the Psalmist. “Praise him with psaltery and harp / Praise Him with timbrel and dance / Praise Him with stringed instruments and pipes / Praise Him with resounding cymbals / Praise Him with clanging cymbals / Let everything that has breath praise God” (Psalm 150:3–6).

The timbrel is also associated with women: Miriam, sister of Moses, led the female Israelites in joyous singing and dancing accompanied by timbrels after the people had crossed the Red Sea, freeing them from Egyptian slavery:

For the horses of Pharaoh went in with his chariots and with his horsemen into the sea, and the Lord brought back the waters of the sea on them; but the children of Israel went on dry land in the midst of the sea. And Miriam the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took a timbrel in her hand; and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances. And Miriam sang to them, “Sing to the Lord, for He is highly exalted; the horse and his rider has he thrown into the sea.” (Exodus 15:19–21).

The title “Timbrel Psalm” evokes both the tambourine and Kernis’s exploration of orchestral color (that is, timbre; the pun on timbrel/timbral was deliberate). Rhythmic and lively, the movement also recalls his fascination with jazz.

The concerto thus has a basic slow-fast-slow-fast structure. The first movement, “Morning Prayer,” features melodic lines embellished with grace notes in the cantorial style we have seen in, for example, Lament and Prayer and Still Movement with Hymn. Kernis introduces true heterophony at one point, perhaps recalling congregational singing. In “Timbrel Psalm” the harp and one register of the piano are prepared by threading paper through the strings to create a jangling sound evoking the tambourine. A virtuosic solo trumpet cadenza features repeated notes requiring triple tonguing and fast passages calling for exceptional technical control. The third movement (“Night Prayer”), in which the soloist plays flugelhorn, is in A B C A' form. It starts with a hymn in the brass followed by an expressive melody in the solo part; the intermediary sections gradually increase in tempo. Before the return to A' the timpani and bass drum lead into a roll and a crescendo on the tam-tam, and then huge block chords recall the opening of the finale of Colored Field. The finale is mostly quick, though it has a lento tranquillo section before the conclusion, which reintroduces elements of the opening before drawing to a punchy, hymn-like conclusion. Two additional solo trumpets here flank the soloist, “floridly mirroring the use of trumpets that purportedly was typical during festival celebrations in the Second Temple in Jerusalem before its destruction,” says Kernis.

The sheer breadth of material Kernis produced in this decade—ranging from the four-minute, jazz-inspired Superstar Etude no. 2 for piano to the monumental sixty-eight-minute Symphony of Meditations for orchestra and chorus—make it difficult to draw conclusions about his compositional direction. The works of this period (and others not discussed, such as the miniature orchestral showpiece On Wings of Light, which Gerard Schwarz calls “three minutes of the most colorful, energetic, jet-propelled music” for orchestra)27 show the assured hand of a seasoned creator, who has refined a distinctive personal style, come to grips with the problems of text and music, built on previous harmonic explorations, and reinforced his own aesthetic principles. Whether his medium was solo instrument, voice, orchestra, chorus, band, or chamber ensemble, Kernis’s sensitivity to color, his balance of consonance and dissonance, and his integration of the varied influences that had shaped his compositional language over the past quarter-century contributed to his maturation as a composer with a unique, articulate, and passionate voice. At the same time, however, the diversity of his output points at new directions, which we will see him beginning to explore in his latest works.