9

The Highest Ground

Once the command of the air is obtained by one of the contending armies, the war must become a conflict between a seeing host and one that is blind.

H. G. Wells, Anticipations

Eric Sundberg needed a rocket engine. Not to propel anything into space, but rather to use its components to burn hydrazine. A joint team of NASA and U.S. Air Force engineers were tasked with developing an on-orbit test to transfer the highly toxic lifeblood of a spacecraft from one tank to another after being connected by a spacewalking astronaut. One of the many problems they were faced with was the fact that a spacesuit glove acted as a wick that would soak up stray hydrazine during the tests. “He’d be a very unpopular person in the crew cabin,” explains Sundberg, “because hydrazine is about half as lethal as saran when you get close to it. When you can start smelling hydrazine, you’re in trouble.”

Walking by an open office door at the Lockheed Missile and Space Company one afternoon in 1984, Sundberg happened to spot an old motor set off to one side of the engineer’s floor. “I’m taking this,” he stated flatly. “This works doesn’t it?” The stunned worker’s head nodded in the affirmative. “Okay, good.” With that, he picked up the old relic and marched out into the hallway with his commandeered rocket engine. But the real fun began when he arrived at the airport to take it back to Los Angeles with him, as Sundberg recalled: “I packed it in a big suitcase and got on an airplane. It was fun because they were just then starting to inspect luggage. And they wanted to know what was in this fairly heavy package, and I said, ‘A rocket engine.’ And the guy looks at me like, oooh, I don’t know about this. And I said, ‘It’s for the shuttle.’ And all of the sudden it’s like ‘It’s for the shuttle’ became magic words because [he said], ‘Oh, yes, let me help you!’”

Sundberg’s caper was just one example of how the manned spaceflight engineer group had to improvise to accomplish their individual assignments within the NASA bureaucracy. From the very beginning of their involvement with the program, they had been coming to terms with just how little the air force knew about the orbiters and how their payloads would interface with them, and in many cases, it fell to the MSEs to make it all work. While the shuttle was physically sized to accommodate DoD payloads, the means to interact with those payloads electronically were never considered in the design.

“It’s like all of the sudden, we don’t know this,” recalls Sundberg, “and then it came time to start looking at flying things in the shuttle, and you say, ‘Well, where do I plug this in?’ Uh, there’s no place to plug it in. Now, physically, was the hole big enough? Yes, but the other parts were not.” These problems became readily apparent when Col. Larry Gooch, then head of the SPO that managed the MSEs, came to Sundberg early in the program and assigned him to develop an instrumentation package to fly on the orbital test flights to measure the dynamic environment of the payload bay during flight.

So, in addition to his developmental tasks with his primary payload, Sundberg and his team also had to scrape together all the necessary parts to assemble the package and make it flightworthy. With time of the essence, Sundberg relates, “we had to go steal parts from everywhere. All the transducers we got—and everything else—we basically took off other programs, put them together, and got them running. Connectors turned out to be our long pole—the RF connectors and electrical connectors. We actually ended up taking used ones, electrostripping them, replating them, and using them because we couldn’t manufacture fast enough.”

The device would be fed data from instrumentation throughout the payload bay, including thermometers, acoustic sensors, and accelerometers. Even though they worked feverishly, it was too much to ask to have the package ready for STS-1, but the team had the equipment ready for the remainder of the test program. The air force needed this critical data in order to confirm that their payloads could safely ride aboard the shuttle, and from the time the requirement was identified, Sundberg’s group had the gear ready to fly in just eight months. “It’s fun to have a project where there’s this tremendous urgency,” he recalls, “because all of the BS and all the posturing goes by the wayside and it’s, ‘Let’s get the job done.’ But [we] got tremendous help out of the Kennedy [Space Center] people and the Johnson [Space Center] people in terms of putting that package together and getting it flown.”

Special Projects (SAFSP) in and of itself was not classified, but virtually every program in which the office was involved fell into that category. The organization was tasked with some of the nation’s most closely guarded secretive space programs, and since the first MSE group was assigned there, it too was kept under wraps. But at the Los Angeles Air Force Station, right across the intersection of Aviation and El Segundo Boulevards, another office building housed the Space Division (SD). This organization was responsible for the DoD’s communications, weather, and soon-to-be-launched navigation satellites.

Since the space shuttle was to be carrying virtually all these military assets into orbit, SD leadership decided to have its own group of engineers selected to accompany its spacecraft into orbit. The group, recruited exclusively from air force personnel, was composed of James B. Armor Jr., Michael W. Booen, Livingston L. Holder Jr., Larry D. James, Charles E. (Chuck) Jones, Maureen C. LaComb, Michael R. Mantz, Randy T. Odle, William A. Pailes, Craig A. Puz, Katherine E. Sparks Roberts, Jess M. Sponable, William D. Thompson, and Glenn S. Yeakel.

LaComb and Roberts were the first women selected for the program; and Holder, the first African American. The group also differed in that they came from a wider range of backgrounds than the first MSE cadre. Some had scientific backgrounds, while several were computer specialists. Two of the new group, Armor and Puz, had held the keys of nuclear-tipped Titan II and Minuteman missiles deep inside their hardened silos, ready to launch them in an all-out strike against the Soviet Union. Only Pailes, a pilot with two degrees in computer science, had any flight experience.

Bill Pailes, born in 1952 in Hackensack, New Jersey, spent most of his formative years in the small bedroom community of Kinnelon. “I did well in school, and I really liked math and science,” he told the authors. He earned an appointment to the U.S. Air Force Academy but was disqualified from pilot training when he failed a color-vision test during his entrance physical. “I wasn’t pilot qualified when I chose my major as a sophomore at the academy, so I was focused on academics,” Pailes recalled. “I really enjoyed my freshman computer-programming course and chose this as a major simply because I liked it.”

Flying had never been a boyhood dream for Pailes, yet in his junior year, he took another color-vision test and unexpectedly passed. The opportunity to become a pilot was something he couldn’t turn down, so he took an assignment to pilot training after graduating in 1974. Toward the end of that training he had to decide what type of flying he wanted to do: “Because flying had not been a long-time goal or aspiration, I gave a lot of thought to what kind of mission I wanted. One of the biggest motivations for me was to have a peacetime mission. I asked specifically for HC-130s because of the variety of missions HCs were used for in the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service—combat search and rescue (SAR) and rescue helicopter air-refueling, equipment drops, and pararescuemen (PJ) deployments, peacetime humanitarian SAR, helicopter deployments, fighter deployment escort, and, sometimes, recovery missions.”

Pailes thoroughly enjoyed his training and assignment as an HC-130 Hercules pilot. Being a devoutly religious person, he found great satisfaction in helping those in need—be they combat troops requiring supplies or a lost civilian hiker seeking rescue from the mountains of Washington State. “I participated in a medivac mission in Iceland, to get a woman—who was pregnant, if I remember correctly—to a hospital,” Pailes shared, and “escorted and air-refueled an AF helicopter out to an Islandic fishing vessel, so a PJ could help an injured fisherman.”

While a copilot in his first operational flying assignment, in the Forty-First Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service Squadron at McClellan Air Force Base near Sacramento, Pailes had the opportunity to fly several air-to-air recovery missions in Panama. Researchers using high-altitude balloons would package their instruments in a pod that was released to descend by parachute, and Pailes helped the aircraft commander snag them in midair. Much like the recovery technique used for the reentry film pods of the military’s spy satellites, long poles extended from the open ramp of the HC-130 with cables strung between them were used to capture the descending parachute with a very close, precisely timed flyover by the pilots.

After a year and a half at McClellan, Pailes flew air rescue missions from Woodbridge, England, for almost three years before returning to earn his master’s degree in computer science from Texas A&M University in 1981. Following graduation, Pailes was sent to a “rated-supplement assignment,” a nonflying position in a computer services squadron at Scott Air Force Base, Illinois, where he could use his new advanced degree. That assignment would be the first in a string of events that would unexpectedly lead to Pailes flying in space:

Early in 1982—I’d just been at my assignment at the computer services squadron for about two months—my wife and I attended a church event, and the speaker encouraged us to just ask God for something . . . kind of personal, something that’s important to us. And I had the thought of asking him for an assignment in the space program. I wasn’t thinking about going up into space, I was just thinking about doing something that was a little more interesting than what I was doing right then. And it was about six weeks later that I read about the MSE program in the Air Force Times. My wife and I talked about it; we agreed that that was an answer to the prayer.

Pailes honestly didn’t think he had even a remote chance of getting selected for the program, given the fact that he hadn’t done anything associated with space in his career to that point. In addition, the ad didn’t even specify a need for rated pilots. “That was not only not a requirement; it’s pretty obvious that that was not an important qualification,” he recalled. Almost immediately, his flying experience caused an issue that could have disqualified him.

In order to be considered, the air force required a rated pilot to have met the first flying gate in their military career, which meant seventy-two months in the cockpit, but Pailes had only seventy-one. Fortunately for him, though, the flight management office took another look at his records and found that they had made a mistake, failing to credit him for his first month of pilot training. “All of the sudden, I went from not being eligible to being eligible,” Pailes recalled. What followed was a comprehensive review of his military records and a thorough medical examination at Brooks Air Force Base, Texas.

The Space Division, however, did not conduct interviews for their group of MSEs. Pailes only needed to provide a recommendation from his unit commander. He’d only been in his current assignment for six months, but after talking to his commander about what he was applying for and because his air force record was good, his commander felt very comfortable recommending him.

The closest Pailes ever got to an interview for the MSE assignment was the psychological exam at Brooks. “Mine was pretty positive, and obviously he must have recommended me, because I guess nobody said no.” When the selection announcement was made in December 1982, Pailes remembers being “a little bit surprised,” yet he reflected on how many things had fallen into place to make it possible. He was able to get his flight records corrected, and given that the project he was assigned to was nearly over, his commander was able to let him go— something that may not have happened had he remained in a flying assignment.

The men and women of the second MSE group reported to SD at the LA Air Force Station in January 1983 and immediately got down to training. Much like the first group, they too were sent to various shuttle and payload contractors for training on various systems and NASA processes. In preparation for their EVA training, they were also sent to the U.S. Navy Dive School in Coronado for scuba training. By the time the second group arrived, however, much of the exploratory work had been accomplished by the first cadre, and the space walk training was more intended to simply familiarize them with the operational environment they were to be working in with NASA astronauts. “I never heard of any MSEs planning to do an EVA,” recalled Pailes. “Beyond the turf and responsibility aspect, I’m sure NASA, for very good reasons, would have wanted to maintain complete control over training and certifying people for EVAs, which are difficult things to do.”

Sundberg would often watch over the new cadre during the course of their training. As a practiced free diver, he could hold his breath longer than most men and would routinely jump into the pool without any breathing apparatus and drop right to the bottom. “They had the safety divers on scuba equipment and everything else, and I could get in the water and go down and sit with them without tanks on,” he recalled. “Yeah, forty feet down—that usually gets people’s attention.”

Another unique opportunity for the second group came when the MSE support office arranged for them to go to the Martin Marietta Corporation to fly the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) simulator. The MMU was to be test-flown on an upcoming mission before being utilized by a NASA astronaut to recover the failed Solar Max satellite later in 1984. “At the Martin simulator, they had this rotating Solar Max thing, and you flew the simulator with the MMU controls to see if you could latch on to it,” recalled Pailes. “It gave us an appreciation for what the Solar Max mission entailed, but it also was a fun thing to do.”

During that first year of training, each member of the second MSE cadre was assigned to a specific SPO—the DoD payload that they would become experts in and presumably fly with. Pailes, along with Mike Booen, was assigned to the Defense Satellite Communications System (DSCS, pronounced “dis-cuss”). Declassified some years later, these spacecraft operated multiple channels of super-high X-band frequencies and were extremely resistant to jamming by potential enemies.

When Discovery returned from the first classified mission in January, the space shuttle program was in high gear, and the DoD’s part in it took on a much more visible and important role in terms of ensuring the nation’s edge in the Cold War with the Soviet Union. But even with the momentum building up toward regular DoD shuttle operations, the air force and the NRO had begun to lament the continuously slipping schedule of what was supposed to become their sole launch vehicle. Proponents for a mixed-fleet strategy, most notably Undersecretary of the Air Force Edward Aldridge, pushed to ensure rapid, timely access to space for the intelligence-gathering fleet of spy satellites.

Within the Special Projects Office, the first signs of frustration had already become evident back in March 1983, when Gen. Ralph Jacobson convened a meeting of the first MSE group for what would come to be known as the Saturday Morning Massacre. The general wanted to make it perfectly clear to his aspiring astronauts that his command had one primary mission—launching critical national security payloads in defense of the United States. The delays in the shuttle schedule were interfering with that goal, and in his mind, it didn’t matter how those secret satellites were launched or that his MSEs were involved. Their dreams of flying in space were of little importance compared to the national security interests of the country.

Things got worse for the team when Secretary of the Air Force Vernon Orr handed down a new directive that officers were not expected to spend any more than four years in a particular assignment before moving on and that any deviation could result in being held back for promotion. Many of the first MSEs had already been at SAFSP longer than that and were forced to begin considering other postings without ever flying in space. One of the first to leave was Eric Sundberg; as he told the authors, “It had become very clear to me that my chances of flying were essentially zero, and by that time, all of the military programs were getting off of the shuttle program itself. And so I had sat down with our director of Special Projects at that time, and he counseled me to move on and asked me where I’d like to go, and he said, ‘I can set you up.’ It had become clear to me that the MSE program had run its course.”

“We were well aware that there were issues between NASA and the air force about military payload specialists being on shuttle flights,” recalled Pailes, “but we MSEs (at least in the second group) did not have to fight those battles.” Even as the DoD and NASA continued to work toward an improved working relationship and the future of the MSE program was not clearly defined, the air force decided to bring on board five new engineers in August 1985—Joseph J. Carretto, Robert B. Crombie, Frank M. DeArmond, David P. Staib Jr., and Theresa M. Stevens.

Paul Sefchek, of the first MSE group, had been attached to one of the air force payloads that was planned to fly aboard STS-62A, the program’s first launch into a near polar orbit from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Like every officer who had signed up for the MSE program in the first place, Sefchek fully expected to get a mission to space. “There were those who wanted to fly because it’s a neat thing to do, and there were those who wanted to fly because of the alpha male type of stuff,” remembered Brett Watterson, who clearly considered Sefchek to be in the first category. But in late 1984, when the air force decided on crew assignments for two upcoming missions, Sefchek’s name was not on the list. The top brass had instead selected Watterson for the historic, coveted position, along with Randy Odle from the second group. According to Watterson, Sefchek was “one of my erstwhile buddies,” and the assignment would strain their relationship.

Fresh from his assignment to the investigation of the IUS failure, Watterson had been far removed from the highly competitive environment of SAFSP for a year and a half. “I neither lobbied for nor said I wanted that job,” he recalled. “I was just called up to the general’s office one morning, and [he] said, ‘We’ve made a decision, and you’ve been selected as a crew member.’ I wasn’t given a chance to turn it down.” Much like the mysteriousness surrounding the astronaut assignments of George Abbey, JSC’s director of Flight Crew Operations, the decisions being made by the air force generals left many of the other MSEs in the dark, and in some cases, animosity would be directed toward the selectees. “A lot of people I thought were friends were competitors,” Watterson revealed.” The angst over his assignment to STS-62A on the part of several of his fellow officers soon washed away his initial excitement from hearing the news.

More politics would soon intervene in the crew assignment for Discovery’s maiden flight from Vandenberg. Pete Aldridge had been representing the DoD in endless meetings with Congress and NASA over shuttle launch pricing, the mixed-fleet strategy, and the possibility of procuring a fifth orbiter. With a price tag of over $2 billion, Aldridge was very publicly opposed to the need for another shuttle. Senator Jake Garn and Congressman Bill Nelson, who would both garner rides aboard space shuttle missions, had been in favor of the fifth space plane, suggesting that as many as thirty-three flights per year would be required to support the space station and the Strategic Defense Initiative.

NASA administrator James Beggs, after accusations that the air force was looking to get out of the shuttle program entirely, secured a compromise with the DoD to purchase as many as one third of the shuttle flights per year. Beggs, in turn, would stop publicly arguing against the production of the expendable launch vehicles. Both NASA and the DoD would work together to design and fund the next-generation shuttle replacement. In attempting to reestablish a cooperative partnership between the two agencies, Beggs made an offer, as Aldridge related to NASA’s Rebecca Wright:

Jim [Beggs] decided that it would be appropriate to have an Air Force official fly. Well, they asked the Air Force official according to the pecking order. The first person on that list is the Secretary of the Air Force. So Jim asked Verne Orr . . . would he be interested in doing that. Orr at the time says no, he would not, because one, he was older; I think he was in his 70s at that time, and the more appropriate person to do this would be me anyway. So Beggs offered for me to fly. Since the Air Force responsibility was to build Vandenberg Air Force Base, the SLC-6 [Space Launch Complex-6] there, it would be very appropriate for the first [Air Force] official to fly out of Vandenberg.

In August 1985 Orr made it official and announced that Aldridge would be a payload specialist aboard Discovery “to illustrate the Air Force’s commitment to the [shuttle], enhance the cooperative spirit between NASA and the Air Force and DoD, and provide valuable insights to guide our future space transportation system developments.”

Decades later Casserino finds it easier to laugh about the arrangement. “Well, the [under] secretary of the air force can kind of go wherever he wants to go,” he surmised. But immediately upon getting involved in the planning for the Vandenberg mission, Watterson realized that the challenge ahead for him was no laughing matter. He found that the justifications for having MSEs on board at all were “less than optimum.” There were two primary payloads on the mission. AFP-675 consisted of a cryogenically cooled experiment to observe auroral and airglow phenomenon, which would remain within the payload bay, and Teal Ruby was a free-flying, experimental sensor package that would be left in orbit.

Watterson had primary responsibility for the stationary AFP-675. “They designed this thing so it didn’t have any telemetry,” he explained, “nor did they route any telemetry through the shuttle, so it was all on tape recorders. In fact, they had built this thing such that it required a payload specialist.” The on-orbit and malfunction procedures for these payloads were a jumbled mess, and the first thing Discovery’s commander Bob Crippen charged Watterson with was to rewrite the “very abstract and obtuse mission plan,” which only the air force personnel could interpret, into a checklist format. Thus, he enlisted the help of group 2 MSE Scott Yeakel and set about reorganizing the procedures into documents the entire crew could understand. “Scott, he was like a brother to me,” remembered Watterson. “He was smart. In fact, there were times if I could say, ‘This isn’t for me,’ I would have forwarded Scott Yeakel’s name. He was a great guy.”

Teal Ruby was a troubled program dating back to 1977. Notoriously over budget and fraught with technical problems, the system utilized charge-coupled device technology in a cryogenically cooled telescope to detect the infrared signatures of missile launches and jet aircraft exhaust in the atmosphere. The two-thousand-pound P-80-1 satellite on which it was mounted was originally intended to be deployed at an altitude of four hundred nautical miles, but shuttle performance from Vandenberg would make that impossible. The mission plan, as Watterson recalled, was for Discovery to take P-80-1 (later designated AFP-888) up to an altitude of 250 to 270 nautical miles, deploy it, and then drop down to 200 miles and spend the remainder of the seven-to-ten-day mission operating his payload.

By early 1985 Watterson had packed up everything he owned and was transferred to the air force detachment at JSC. There, he took up residence in building 4 and would soon become an officemate and friend of teacher-in-space selectee Christa McAuliffe and her backup, Barbara Morgan. “I couldn’t tell anybody why I was down there,” he explained. “And really why I was down there was, one, 62A was an important first-of-a-kind mission, but second, I think it was the way they had to get me out of Los Angeles, because I had too much time on station.” With eight years tenure at Los Angeles, getting reassigned to detachment 2 in Houston allowed Watterson to avoid being sidelined by Secretary Orr’s recent directive.

On 15 February 1985 the crews for two upcoming classified missions were named. Karol (Bo) Bobko’s crew would eventually become STS-51J, and Bob Crippen’s would undertake the inaugural Vandenberg flight. Just ten days later President Ronald Reagan signed the National Security Launch Strategy, directing the air force to purchase ten expendable launch vehicles and “launch them at a rate of approximately two per year during the period 1988–92.” As had become the norm, no MSE payload specialists were publicly named with the NASA crew announcements. But at the program’s headquarters at the Los Angeles Air Force Station, the word had come down—Odle was replaced on STS-62A by Aldridge, and the next DoD mission to fly in the fall of that year would include an MSE from the second group, Maj. William Pailes.

STS-51J would loft the first two DSCS III satellites, and as it turned out, these came from the SPO that Pailes was assigned to when he joined the MSE program. When the decision was made to fly an MSE on STS-51J, the air force decided to draw from that office. “Theoretically, every MSE in my group was a candidate,” explained Pailes, “but SPO assignment, apparently, was a big factor.”

Pailes would be joined by his backup Michael Booen, also of the second group, in training for the classified mission. The news came as Frank Casserino and Daryl Joseph, who had been left in limbo with their payload when the IUS failure occurred, still waited for their first spaceflights. Their payload had not yet been remanifested, and now they watched as two officers selected for the program after them were assigned to a mission just a few months away.

Casserino and Joseph had been targeted for STS-16 when the original assignments were made in the summer of 1983. “Daryl was seven years older than me,” Casserino explained. “He graduated from the academy in 1970. I graduated from the academy in 1977.” Yet it was Casserino who got the prime MSE spot for the mission.

When the time came and I got a call from General [Ralph] Jacobson and he told me, “Frank, congratulations, you’re identified as the primary payload specialist,” I was just as blown away about that as I was when I got selected for the program back in 1979. So, it was great; it was humbling. Daryl, then, even though he was seven years my elder, basically was my protector. His attitude was, “I’m gonna protect you from NASA; I’m gonna protect you from everybody. You’re gonna be the most successful payload specialist, and then I’m going to fly after you.” Daryl ended up being a great friend and a great partner.

But for now, all the pair could do was watch as the first two DoD missions were flown in 1985 and as planning progressed for the high-profile Vandenberg flight.

Construction of the Vandenberg launch facility was nearly completed by the fall of 1985. The launchpad, service structures, and two new flame trenches had finally come together. Additional facilities to receive and service the SRBs and external tank were being prepared to accept hardware. The orbiter processing facility was constructed near the facility’s newly extended fifteen-thousand-foot runway at the north base, requiring an arduous twenty-two-mile road journey for the shuttle on the way to SLC-6.

Many challenges still lay ahead before the facility would be ready for Discovery to begin operations from it, the most serious of which being the possibility of unburned hydrogen being trapped in the curved exhaust duct and causing an uncontrolled fire or explosion. Acoustic overpressure reflecting off the launchpad and even the surrounding mountains threatened to damage the orbiter and the service structures during launch. Even the launch control center full of personnel was at risk, being located just 1,200 feet from the pad.

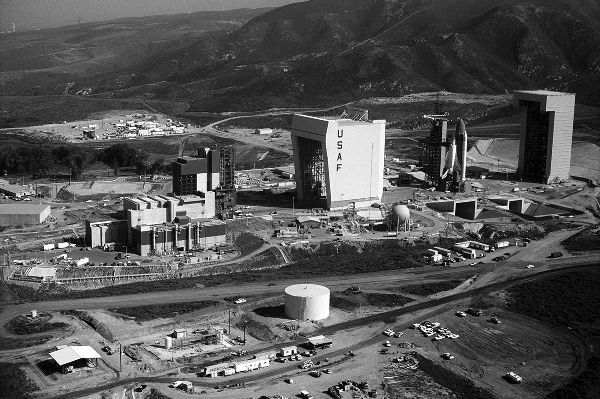

23. Space shuttle Enterprise stacked for fit checks at Vandenberg Air Force Base’s Space Launch Complex 6 in February 1985. Critical to the DoD’s plans for polar-orbiting classified missions, the facility was plagued with technical problems, and no shuttle would ever launch from the West Coast launchpad. Courtesy U.S. Air Force/Retro Space Images.

In addition to the issues surrounding the launch facilities themselves, operational risks for the shuttle’s ascent were a top priority. “There were abort gaps, which violated flight rules,” explained Watterson. “We were firing on 109 percent SSME [space shuttle main engine] thrust.” To cut down on weight and meet the air force requirement to loft a thirty-two-thousand-pound payload into polar orbit, new filament-wound SRBs were to replace the typical steel-cased boosters, and their development was plagued with technical problems. Former flight director Glynn Lunney shared in his NASA Oral History interview that “Vandenberg was a tough place for us, because it’s very windy and it tends to be kind of rainy and cloudy, so a difficult launch, but even more difficult landing site for the orbiter.” As Watterson concluded to the authors, “There was a lot of derring-do on our mission.”

A dramatic glimpse into the future occurred at SLC-6 in February 1985. With the planned maiden flight from Vandenberg still several months away, the prototype orbiter Enterprise was rolled from the processing facility at the north base and driven on a purpose-designed transporter down to the base of the launchpad. There, inert SRBs and an external tank had been stacked awaiting the shuttle for fit checks and prelaunch-procedures testing. Unlike the process used for decades at KSC, the air force would erect the stack on the launchpad and enclose the shuttle inside the massive, movable Shuttle Assembly Building and mobile service tower. It was a surreal sight, with the space shuttle pointing skyward in stark contrast to the backdrop of California coastal hills and the nearby Pacific Ocean shoreline.

Walking through Red Square in Moscow in early 1975, Karol (Bo) Bobko glanced over at Bob Overmyer: “I never doubted that I’d be here. I always thought it would be at two hundred feet and at full afterburner.” The two former Manned Orbiting Laboratory astronauts had spent a majority of their military careers training to fight and later conduct espionage from space against the great juggernaut that was the Soviet Union. As Bobko shared with NASA’s Summer Bergen in a 2002 interview, they now found themselves part of the American delegation working toward the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the first joint mission between the Cold War adversaries.

“I think we were the first people to be down at the launch site in Kazakhstan and to know the Russians, to learn to speak Russian,” he related. “So that was an interesting couple of years.” A decade later, those days of détente were long past, and as the pendulum of history swung back toward chillier times between the two countries, Bobko found himself at long last in command of a military mission to space. Joining his STS-51J crew late in training from his April mission aboard Discovery, he would now command the first mission of Atlantis, with its twin DSCS III spacecraft stacked on a single IUS.

Now heading into his third training cycle, Bobko easily assimilated himself into this crew of mixed experience. Pilot Ron Grabe, mission specialist Dave Hilmers, and Pailes were all rookies, while Bob Stewart had one spaceflight under his belt, test-flying the Manned Maneuvering Unit on STS-41B in early 1984. For the two MSEs assigned to the flight, the transition to being crew members could not have gone smoother, as Pailes recalled: “After I was assigned to my mission, not only did I have absolutely no difficulties with the NASA crew members, but they accepted me completely. Maybe that was a function of the specific individuals, but [they] made me feel as though I was a full member of the crew. The NASA training and support personnel, at both JSC and KSC, treated me and Mike Booen as though we were NASA astronauts. I neither encountered nor sensed any ill feelings, let alone animosity, at all.”

Many of the technical challenges experienced by the first DoD mission crew with their IUS payload were smoothed out in the intervening months, but classification still remained a stumbling block. Checklist books used by the crew for post–orbital insertion and deorbit preparations would have pages of classified changes added to them. “We found this system to be cumbersome, confusing, and possibly error producing,” Bobko pointed out. In one example of the inefficiency of the flight documents, an entry in the deorbit checklist instructed the crew to “perform payload safing.” This led the astronauts to another classified checklist for the payload, which in turn referred them to a third document, which incredulously read, “No action required.”

Secondary payloads on the classified mission became a serious issue as well. “This process evolved as it was ‘discovered’ that our flight existed and that room might be found for additional experiments,” Bobko said of the increasing burden on his crew. Even up to just one month prior to flight, more and more proposals kept coming forward to be stashed aboard Atlantis. The major problem for Bobko to contend with was that given the secrecy surrounding the flight, most of the procedures for these experiments had to be developed by the crew members themselves, due to the complications associated with getting clearances arranged for an increasing number of engineers.

Early on the morning of 3 October 1985 Bill Pailes stood on the launch tower platform 195 feet above pad 39A, waiting for his turn to board Atlantis. Admiring the beautiful, clear, peaceful Florida morning, he took a moment to consider what he was about to undertake:

I could hardly believe that I was where I was—just a couple of hours away from going into space. It wasn’t that it didn’t seem real, because everything about it was very real. It was that I was so fully aware of and so very appreciative of the fact that, not only was I participating in a space shuttle mission, which thousands of people had worked on, but I was in one of the most privileged of positions—the crew members—the people who get to see and experience the culmination and very purpose of all those people’s efforts. I was so thankful.

As had been the case with STS-51C, the morning rituals of a departing space shuttle crew were kept from the view of the public, in order to foil any predictions of the exact launch time. The countdown clock held firmly at T minus nine minutes, leaving reporters and family members to wait impatiently for the first movement toward launch. Atlantis, being a factory-new orbiter, had only fired its engines once before, in a flight readiness firing test on the pad a few weeks before. Now poised to carry out a critical mission to help ensure the nation’s security, the shuttle presented few problems for the crew and technicians to address.

Without warning, the clock suddenly started ticking down the final nine minutes. “It was at that point that the realization that I was about to go into space struck me, and I got really excited about what was about to happen,” recalled Pailes. “The reason, I think, this didn’t happen earlier is that up until those final [nine] minutes, there always was something else that had to be done before the mission. After the hold was done, there was nothing left to be done before the launch. It really was about to happen!”

Finally, at 11:15 a.m. Atlantis roared to life once again. The hold-down bolts were blown, and the shuttle took its first leap off the Florida pad into what would become a storied career. For the first-time payload specialist seated in the middeck, it was an unforgettable ride: “The launch itself was absolutely incredible! I could feel the main engines start, and when the SRBs lit, we were off the pad instantly. The shuttle accelerates faster than a T-38 on takeoff roll and reaches one hundred miles per hour by the time it clears the launch tower. The force of over 6.5 million pounds . . . is amazing. And it was thrilling—nothing unpleasant or the least bit frightening at all. A fantastic ride!”

Pailes would remember over three decades later that he felt absolutely no fear during the impressive ride to orbit. “It wasn’t because I’m any more courageous than others,” he said. “My definition of courage is doing something that is scary. This was not, to me.” While launching into space was a big jump from flying military aircraft, he saw it as a reasonable progression both in performance and reliability. “Military pilots are success oriented. We expect the planes to work, so we don’t dwell on the possibility of failure,” he concluded.

As Bobko and pilot Grabe worked feverishly through their post–orbital insertion checklists, they wanted to snap a few photos of the slowly tumbling external tank as it drifted away from Atlantis. On the middeck, Pailes unstrapped and floated over to an equipment locker. “I’m downstairs in the middeck and Karol Bobko gave me permission to get out of my seat,” he remembered. “I got a camera out and floated up to the flight deck and gave it to Ron Grabe, who could look out the front window and take a picture of the tank. [It was] fun right away,” he said. “It took me just a few seconds to feel comfortable. I’m sure I got better at stabilizing myself over time, but it felt natural and easy immediately.” Contrary to Payton’s initial reaction to the alien environment, Pailes thought the experience of the Vomit Comet had indeed helped him in adjusting to space.

Shortly after the payload bay doors were opened, he floated to a window to see “the most impressive view” of the curved blue horizon of Earth filling the upper portion of the windows of the upside-down orbiter, and the top of one DSCS III satellite sparkling in the harsh, unfiltered sunlight. For Pailes, it was a very spiritual experience. “When I first looked at the entire scene outside the payload bay windows, with the spacecraft in the bay and the earth above, I couldn’t help but marvel at God’s creation, and I felt small and insignificant in comparison,” he recalled. “But God didn’t let me stay on that thought, because He conveyed to me that although I obviously am small in size, I’m more important to Him than His creation.” It was a powerful moment.

Mission specialists Hilmers and Stewart got to work preparing for the deployment of the double-stacked communications satellites on their IUS booster. As the tilt ring was raised up to the proper position, Pailes carefully examined and photographed the two spacecraft and the cylindrical white booster rocket—the same type that had sent Payton’s payload to orbit nine months prior. Several orbits into the mission, at the precisely defined time that the launch had been keyed to, the IUS completed its automated countdown and was sprung from the grasp of its launch support.

24. Atlantis’s payload bay doors are opened to reveal two Defense Satellite Communication System (DSCS III) spacecraft stacked one atop another on their interim upper stage (IUS) booster rocket. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

Gliding ever so slowly up into the inky blackness of the dark side of Atlantis’s orbit, the twin spacecraft began their journey to a high perch above the planet from which they would route military communications for years to come. “Deployment of the satellites was a very straightforward process,” Pailes related. “[Simply] releasing the stack and letting it drift away from the orbiter.”

Bo Bobko made a mental note for his postflight report as he finished the complicated procedure of “taking care of business” without the beneficial effects of gravity. A “coffee can” with a plastic bag insert was used to dispose of wet tissues, which would then be tied closed and placed into a wet-trash container. “The entire operation was clean and efficient,” the commander later wrote, but “the reason for clear plastic sides on the bag is not apparent as none of the 51-J crew members felt inclined to inspect the contents of the bag during its transport to the wet trash compartment.”

Only two technical issues came about that required the crew to perform in-flight maintenance: one repair to an electrical box on one of their secondary experiments and the routine filter cleaning. The latter led to Bobko reporting a minor theft following the mission, in his typical, understated humor: “A large number of hardware items were encountered and collected mostly by hand. These articles consisted mainly of screws, nuts, bolts, and fasteners. The largest article encountered was a substantial coaxial cable connector assembly. One U.S. quarter dollar coin was also collected.” But after landing, Bobko noted that these “space-flown” items, including the quarter, had been pilfered by ground personnel. “This deprived the 51-J crew of their hard earned flight bonus of 5 cents each!”

Over the course of the brief four-day mission, the crew performed several experiments and more medical tests. A black-hooded device designed by astronaut Jeff Hoffman was placed in the orbiter’s windows to block cabin glare while photographing various celestial phenomena. Pailes reveled in the zero-g world of orbiting the planet as he undertook his assigned tasks. “The weightlessness was fine, I was comfortable with that,” he said. “It just felt right. It felt the way it ought to be.”

It wasn’t until the second day of the flight that he had a true opportunity to look at Earth from a place he never imagined he would. The impression he was left with was somewhat different from many others. “Being in Earth orbit is different from being out in space returning from the moon, so you’re not seeing a ball in the windscreen; you’re seeing a big disk,” he related. “I just found the whole thing to be thrilling, but I couldn’t get away from the creation standpoint. I had a chance to look at Earth—this planet that God created—from 350 miles up, and it was just great!”

But in addition to the spiritual experience of it, one other feature of the planet immediately stood out to Pailes: “I didn’t look at the earth as being fragile. It didn’t strike me as being fragile at all. I saw it as a remarkably sturdy planet. I thought to myself, ‘God made a good planet. He made a really good planet that’s serving the needs of the human race.’ That’s not to say I’m indifferent to environmental things, because I’m not. That simply was my reaction, but it doesn’t mean anybody else’s reaction, just because it was different, was any less legitimate. They’re all legitimate.”

25. Manned spaceflight engineer Bill Pailes, camera in hand, in the middeck of Atlantis during its maiden flight, STS-51J. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

The one surprise that came to Pailes during the mission was the nighttime view of the sky literally blanketed in pure-white, sharp, clear stars. “There were more stars than you can see below the atmosphere,” he remembered. “I was really kind of surprised at how many.” It reminded him of the view from high atop a Colorado mountain on a clear night, only “double that.” On the morning they would return to Earth, Pailes awoke early and, like many of the other payload specialists who had flown, took one last opportunity to savor the wondrous beauty of the planet from space. “I’d have enjoyed a couple more days,” he recalled. “It’s almost like four days—you’re just feeling really comfortable, you’re enjoying yourself, and now you’ve got to go home. But I was and still am thankful for the time in space we had.”

Atlantis arced across the Pacific Ocean on its first reentry enveloped in a neon-orange sheath of plasma. “The high heating phase of the entry was at night with the crew able to witness significant entry glow,” Bobko wrote after the mission. “The orbiter was encased in [a] glow that became brighter as the RCS jets were fired. It appeared as if the Orbiter was flying through an orange-yellow cloud with an occasional lightning strike nearby.” Pailes, seated back in his launch position next to the tiny hatch window, described it later as a very smooth flight, with a gentle buildup to not more than 1.5 g’s. In observance of the protocol for every maiden flight of an orbiter, Atlantis would return to the wide-open expanse of Edwards Air Force Base. Having blown a tire on Discovery just a few months prior while landing at KSC, this suited Bobko just fine.

After slowing to subsonic speeds and taking over manual control, Bobko glided the orbiter to a perfect landing on the concrete runway at Edwards under a clear blue sky with a ghostly crescent moon above. As he slowed with the touchy wheel brakes, though, he felt the right brake pressure being released automatically to prevent yet another skid. “Since we had been briefed that at speeds below 130 knots, it was practically impossible for the anti-skid to release, the [commander] assumed it was a skid and backed off on the brakes,” he reported.

With the call of “wheels stop,” loudspeakers at the desert landing strip blared out the “Star-Spangled Banner” for the small number of spectators and reporters present to hear it. Atlantis still looked virtually brand-new after just four days in space, having travelled 1.7 million miles on its maiden voyage. Upon postflight inspection, though, a significant gash was found in the trailing edge of the left wing—likely caused by a loose gap filler that blowtorched hot plasma onto the spot during entry.

Bill Pailes immediately began readapting to the heaviness of living on Earth, having been off it for several days. “The entire experience was an incredible opportunity. There were no downsides. The NASA crew was great, and working with them was a real pleasure. The actual experience of going into space was absolutely incredible!” But as meaningful as it was to him that he had been part of a vital national security space shuttle mission, he firmly believed that the best part was that God had put him there. “Applying for the MSE program had been His [God’s] idea, and He had gotten me past a couple of the hurdles in the application process. I believe He had orchestrated my selection as an MSE, had arranged my assignment to the DSCS SPO, and, finally, my selection to be the [payload specialist], and the final agreement to include me on the mission.”

Bobko would continue to struggle with some of the awkward arrangements caused by classification following the mission, but for the most part, many of the issues that had pervaded the first DoD mission had been ironed out. “This entire operation was greatly improved over 51C and shows significant development of the system,” he reported. “The smooth working relationship with DoD is also an indication of a mutually maturing relationship that allows complex missions to be effectively flown.”

For Pailes, it seemed everything had fallen into place, and he was even looking forward to another opportunity to fly again as an MSE. “Right after my flight I was told that I might very well go on the next DSCS mission,” he recalled. But the events of the next few months would change everything for the MSEs who remained as part of the air force’s dedicated corps of astronauts.

On 25 August 1985, just weeks before the STS-51J mission, a Titan 34-D launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base failed during ascent and deposited its top secret payload into the depths of the Pacific Ocean. The workhorse expendable booster favored by Aldridge for its capability to launch on demand would now find itself under scrutiny. But no one in the intelligence community could have imagined what would happen over the coming months. Challenger and its crew of seven would perish on 28 January 1986. Barely four months later the unthinkable happened—on 18 April another Titan 34-D, carrying the last Hexagon satellite, exploded spectacularly as it left the launchpad at Vandenberg. A strap-on solid rocket motor had blown apart and destroyed the vehicle, leaving behind a cloud of flaming tentacles that engulfed the pad area like a gigantic smoky octopus. For the immediate future, the DoD had no means of replenishing its critical flotilla of reconnaissance satellites to protect the country.

With the loss of Challenger, the fate of the MSE program was sealed. No one knew at the time how long it would be before the shuttles were able to fly again, but when they eventually did, the air force would have no further interest in having their own personnel accompany classified payloads into orbit. For many of the officers that remained in the MSE program at the time, there was little left to do in the wake of the accident. The program was officially terminated in 1988, and by June of the following year the Manned Spaceflight Control Squadron in Houston was disbanded. After an estimated cost of $5 billion, the SLC-6 launch site at Vandenberg was mothballed and the air force’s Consolidated Space Operations Center in Colorado Springs was, for a time, transferred to the Strategic Defense Initiative.

The MSEs would all move on to other assignments or out of active service altogether. It would be two and a half years before the shuttle once again rose from the Florida coastline, and the air force would have to ground several clandestine payloads that could only be launched on the orbiters until they were manifested onto a handful of early postaccident missions. “After the Challenger accident, you couldn’t separate fast enough,” Frank Casserino recalled. “The air force was happy to get back to controlling everything on their end, and NASA was happy to get back to controlling everything on their end.”

Casserino and Daryl Joseph had been deeply involved with their top secret payload before the IUS failure occurred in 1983. Casserino was to have finally flown into space with that satellite aboard STS-61N in September 1986. Following the loss of the shuttle, that payload had been placed aboard Columbia’s STS-28 mission, commanded by Brewster Shaw. By August of 1989, when their payload was finally launched, the MSE program was a distant memory, but Casserino and Joseph found themselves side by side at the Satellite Test Center in Sunnyvale supporting the mission—their mission. “I had left the air force shortly before the flight, and I was a civilian contractor with the air force to support shuttle missions,” Casserino explained. Joseph was a lieutenant colonel still on active duty and had been assigned to Sunnyvale as well.

Casserino remembers today that, serving once again as paycoms, “[We were] watching the mission that we would have flown going on saying to ourselves, ‘Boy, we should have been there.’” As they monitored their payload from consoles within the Blue Cube, their thoughts rarely strayed far from what could have been. “It was an interesting way to end that whole thing for us,” he shared. Immediately following the Challenger accident, Casserino had been assigned to help reintegrate DoD payloads back onto the expendable launch vehicles, except for those that could only be accommodated on the shuttle. He would continue to work with the STS-28 crew closely, particularly mission specialist Mark Brown, in the months leading up to their flight.

When Columbia launched to deploy the DoD payload on the third post-Challenger mission, the crew took along a photo of Casserino and Velcroed it up in the aft flight deck. Today, framed on his office wall is that very flown photo, along with a photo of the crew with his image on the flight deck in orbit, as if he were part of the crew. Brown had inscribed on the photo, “I’m sorry you weren’t there in person, but at least you had this picture. Hope to see you soon. Sincerely, Mark.” It was a heartfelt tribute to Casserino’s dedication to the mission but also a sad reminder of the loss of a dream.

Casserino would continue to serve in the U.S. Air Force Reserves for almost twenty-four years, retiring as a major general. One of his proudest accomplishments was the development of the first space-dedicated unit in the reserves, the Seventh Space Operations Squadron, in 1993. As he recalled, “[I] got blessed in my career on the reserve side from there, because of all the good people who made me look good and develop to the point that the program that I started with twenty people is now the first Air Force Reserve space wing with over a thousand people in it, which was pretty cool.” Even after retirement, Casserino has on occasion returned to his old unit to reunite with the officers, airmen and airwomen who carry on the mission today. At an April 2017 awards ceremony, the current commander of the 310th Space Wing introduced the former MSE as the “founding father of space” in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.

Following the disbanding of the MSE team, Brett Watterson transferred to another classified assignment in Germany as a station commander for three years. Today, he admits that he “had some interesting feelings about being that close to flying and not flying.” It was the most disappointing “professional regret” he had ever experienced, having put as much as any other air force officer into the program and its mission. But he was able to harness those feelings and experiences later when he was involved in space policy making at the Pentagon, before returning to southern California and retiring a full colonel in 1997.

He would join NASA at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory as the director of system safety, a career that he carried on to the Aerospace Corporation before retiring for good in 2010. At a 2005 reunion of the STS-62A crew hosted by Bob Crippen in Houston, Watterson was joined by all his old crewmates with the exception of Aldridge. In light of the many issues that conspired to delay that flight beyond the tragic loss of Challenger, he recalls that “even though it was a mission filled with risk, everybody—to a man—regretted not flying on that.”

Watterson is today still very adamant about one point—“I’m not an astronaut,” he insists. Even though he invested so much of his life to the space shuttle program, trained as an astronaut, and was assigned to a high-profile mission, he prefers to refer to himself simply as a crew member. “I think that’s right,” he rationalizes, “because I wasn’t just watching; I was participating in the mission’s success.”

Eric Sundberg enjoyed a long career in the air force, government, and civilian sector after the MSE program. After several challenging assignments in the space command and as the space chair at the Air University at Maxwell Air Force Base, he was promoted early to colonel and landed a job at the NRO Headquarters in Washington DC. He would spend seven years there before retiring from the air force in 1997. Through an intergovernmental personnel assignment, he was hired by Georgia Tech and returned to the same NRO offices as a civilian.

Sundberg later left the NRO and joined the Aerospace Corporation just as Watterson had done. When asked if he holds any regrets over not flying in space, he responds with an emphatic, “Well, yes! There is a voyeuristic part of that that says absolutely.” But there was an important lesson, in Sundberg’s notoriously analytical mind, that came out of his time in the MSE program. “I spent five years training for something that would last between three and seven days. That’s not a good ratio.”

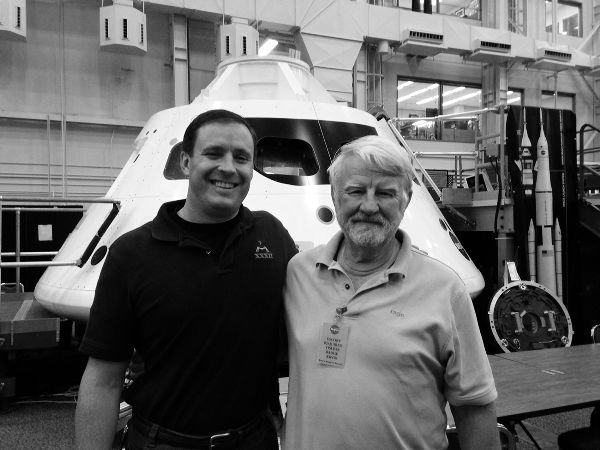

As a senior colonel in the NRO organization, Sundberg was often asked to give motivational talks to contractors and air force personnel on the space activities of the military. During one such visit to the Air Force Academy, he had a chance meeting that would change his life: “I met a young cadet who I just related to perfectly. His name was Jack Fischer. It turned out that Jack had just lost his Dad. He was a little bit in the confusion of where he was going, and at the same time, I had just lost direct contact with my kids through a divorce. The two of us gravitated toward each other.”

Sundberg brought Fischer and several other cadets out to Washington one summer to give them a glimpse into the NRO’s activities and then arranged for them to spend some time working at the nearby Naval Research Laboratory. “Over the years, we became closer and closer until we effectively became family,” Sundberg reflects. As their relationship grew and Fischer was commissioned and got married, he and his wife would ask Sundberg to become a surrogate grandfather to their children, an honor he happily accepted. “It’s nice to be able to choose your family,” he says.

“One of the reasons Jack and I got along so well is that I had this dream of flying on the shuttle and flying in space, and he had the dream of flying in space,” shared Sundberg. Fischer would go on to become an F-15 fighter pilot, attend the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School, and do test work on the F-22 program before being selected as a NASA astronaut in 2009. On 20 April 2017, after years of training and waiting, Fischer launched to the ISS from Kazakhstan aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft along with cosmonaut Fyodor Yurchikhin. Sundberg made the long trip to Russia to see him off and was able to greet him by radio later that day as the hatches between the Soyuz and the orbiting laboratory were opened. Beaming with pride, the former MSE told him simply, “Jack, you are living my dream.” Fischer responded with a heartfelt, “Well, sir, I’ll do the best to make all I can out of it and appreciate it for the both of us.”

Gary Payton never flew in space again, but success continued to follow him in the ensuing years. After nearly a decade at the Pentagon in Washington, he retired from the air force and went to work for NASA, involved in the development of various next-generation vehicles to replace the space shuttle. In addition to management of the X-33 and the X-34 technology demonstrators, Payton would cross paths with moonwalker Charles (Pete) Conrad from McDonnell Douglas while pursuing the DC-X vertical takeoff and landing test vehicle. Single-stage-to-orbit concepts have been investigated vigorously, but to date, it remains an elusive goal.

26. NASA astronaut Jack Fischer (left) with MSE Eric Sundberg. The two met when Fischer was a cadet at the U.S. Air Force Academy, and they became lifelong friends. Fischer would launch on his first mission to the International Space Station in April of 2017, accumulating more than 135 days in space and nearly six hours of EVA time over two space walks. Courtesy Eric Sundberg.

One project from Payton’s NASA days did prove successful, though—the X-37A would be transferred from NASA to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in 2004 and would lead to orbital flight tests and the eventual X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle, the air force’s own version that is still in use today. A smaller-scale unmanned space plane design, the winged vehicle has conducted several top secret missions in orbit, one of which notably lasted nearly 718 days before gliding to an automatic landing at Vandenberg Air Force Base in May 2017.

In 2005 Payton was named deputy undersecretary of the air force for space programs. Reporting directly to the secretary of the air force, he recalls these days as “Mr. Space” at the Pentagon as some of his most rewarding: “I got in on starting a whole bunch of things, some of which have been successful, some of which are not. The X-37’s one of them. I started it the first time—I was at NASA Headquarters—but then worked on it again when it became an air force project. I also started something called Operational Responsive Space, which was another success. I pushed through the Pentagon bureaucracy on new technology demonstrations on orbit that will be the foundation for the next generation of our missile-warning satellites.”

Today, Payton has returned to the Air Force Academy, where his journey to space began. As an endowed professor in the astronautics department, he teaches classes in human spaceflight, incorporating the lessons of the Challenger and Columbia accidents into a curriculum for a new generation of military aerospace leaders. Payton also mentors engineering cadets in the academy’s FalconSAT Program, in which students design and build small experimental satellites for launch into space. Of his experiences passing the torch to the air force’s newest officer corps, Payton relates that “the highlight of this job has been being asked four times to swear in cadets to their commission into the air force. Seeing these bright-eyed, bushy-tailed brand-new lieutenants march off into the sunset is great.”

Bill Pailes returned to flying the HC-130 after leaving the MSE program in 1987. “The air force for good reason said, ‘You need to go back to flying, you’re a pilot,’” he recalled. “And I couldn’t come up with a good enough reason to not do that.” The rescue birds were being transformed into a Special Operations mission, “flying at very low level on night vision goggles. It was all more secretive,” Pailes said of his new mission.

After a staff assignment to Twenty-Third Air Force headquarters—which became Air Force Special Operations Command during his tour there—and almost a year at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, he spent the remainder of his military career at the Defense Information Systems Agency, retiring in 1996. Upon entering civilian life, Pailes answered a call to become an assistant pastor at his northern Virginia church, where he spent three years. In 1999 he entered the business world as a consultant for the Swedish company Mercuri-Urval, where he would serve until the post-9/11 recession. But that pivotal event was what led him to an opportunity he had always had a desire to pursue.

He had moved his family to his wife’s home state of Texas in 2000, and with time to now contemplate his future, he learned of an opening as a Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) instructor at a local high school. “I had always wanted to get into teaching in some capacity but hadn’t given it a lot of thought,” he recalled. While he was simultaneously offered a position at Baylor University, “my wife and I prayed about it, and we felt God said he wanted me to teach Junior ROTC.” With nine years at Corsicana High School and now six at Temple High, he has no current plans to quit.

People sometimes politely ask him, “What’s a former astronaut doing teaching high school?” but Pailes doesn’t look at it that way. “If God wants me to do something, I care what it is, but I don’t really care what prestige is associated with it,” he shared. He happily accepts the astronaut title, with one caveat—“I point out that I was an ‘air force astronaut’ and not a NASA astronaut,” he said. “The distinction doesn’t seem to be important to people, but I don’t want to give the wrong impression.” During the course of the JROTC program, his students hear firsthand about his experiences flying, his time as an MSE, and the history of the air force in space and its corps of Manned Orbiting Laboratory and shuttle astronauts.

In June 2011, for the first time since his only spaceflight a quarter century before, Bill Pailes went to KSC to witness a space shuttle launch. Having flown on its inaugural mission, he took the opportunity to witness Atlantis’s last, STS-135. After a brief, unplanned hold, his old ship and the four-person crew roared from the launchpad to be quickly swallowed up in a low deck of clouds. “And that was the only one I saw from outside the shuttle!” he says with a chuckle. “So I’m glad I had that opportunity to get down there for the last one.”

Of the thirty-two MSEs selected, five would go on to become generals in either the active-duty air force or reserves. Michael Hamel and Frank Casserino of the first cadre and James Armor, Larry James, and Katherine Sparks Roberts of the second group would all attain one star or more in the years that followed. “You had a totally disproportionate number of MSEs made general officer,” Sundberg remembers proudly, “and those who didn’t make general officer, a very large portion of them, made colonel—beyond what would be normal air force statistics.”

Many of them crossed paths later in the aerospace world and still stay in touch today, holding each other in the highest regard. Like any group of highly trained, competitive professionals, some had their differences and as a result lost touch over the years. Some have passed on, and in a tragic twist of fate, Charles Jones of the second MSE group would lose his life aboard American Airlines flight 11, at the hands of terrorists, on September 11, 2001.

Looking back on those early years of the space shuttle program and the military’s involvement in it, those who had the chance to participate offer a wide range of opinions about its legacy. “The MSE program was probably an interesting way to try to get two large organizations to work together,” offers Payton. “We ended up being a lightning rod to focus attention on the relationship between the air force and NASA.” Ken Mattingly was once quoted as saying, “I sometimes thought the only people in the air force really interested in the shuttle were the MSEs.” Loren Shriver, Mattingly’s pilot on that first classified mission, suggests, “I think this expression may come from the situation the air force was in. They basically agreed that the shuttle would become the sole launcher of DoD payloads, and I think many in the air force were very uncomfortable with this arrangement. Their concerns were made real by Challenger. For over two and a half years, the air force was left without a launch vehicle for major national security payloads. Quite frankly, it would be hard to dream up a more serious blunder for national security than to limit their space launches to a single launch vehicle.”

Pailes agrees that the decision itself turned out to be somewhat flawed. “I know the air force didn’t want to have to use the shuttle for its launch vehicle, because it was more expensive, more complicated, a security nightmare, and, really, unnecessary,” he offered. Looking back on the MSEs’ viewpoint at the time, he often says that flying on the shuttle was something they would “get to” do, while the air force was told, “This was something you’ve got to do.”

But once the directive was made clear, the two organizations made history by learning how to make the arrangement work. In Pailes’s mind,

I think it’s simply an example of a U.S. military service making the best of a situation after being directed to do something that, basically, made its job harder and not easier. And once committed, wanting to put its own officers on flights was a logical and reasonable idea. As far as the MSEs themselves are concerned, who can fault them for being motivated after being ordered to do something so exciting? Finally, and this probably is the most important part, without help from the DoD to pay for the shuttle program, perhaps the program wouldn’t have been nearly as successful.

He would also point out that even though objectives didn’t “mesh very smoothly all the time,” most of the issues between the space agency and the air force were either resolved or nearly resolved when the program was brought to an end. “Probably half a dozen other MSEs, some in SD and some in SP, were programmed to fly,” Pailes points out. “If it hadn’t been for Challenger, I think the MSE program probably would have turned out to be a pretty good thing with a lot of successes, but we’ll never know.”

The culture clash between the DoD and NASA over the secrecy required of the classified flights still lingers in the memories of the astronauts. Mattingly related to NASA’s Kevin Rusnak, “I still can’t talk about what the missions were, but I can tell you that I’ve been around a lot of classified stuff, and most of it is overclassified by lots,” he explained. But he shifts from that opinion somewhat when recalling the top secret shuttle missions. “What those programs did are spectacular. They are worth classifying, and when the books are written and somebody finally comes out and tells that chapter, everybody is going to be proud.”

Payton’s and Pailes’s flights aboard the space shuttle were the vindication of decades of failed programs, interagency conflicts, technical challenges, and politics. The Manned Orbiting Laboratory and the X-20 Dyna-Soar never got off the drawing board, save for one unmanned test launch, and the space shuttle would never live up to the heady assumptions of NASA, the DoD, or the politicians who attempted to force them into an unwilling partnership.

The men assigned to cram their ultrasecretive national security payloads into a vehicle that wasn’t designed to carry them faced hurdles not only in the hardware but also in a civilian organization with a strong heritage of doing things in its own way and in the full view of the public. However, the promise of ensuring the nation’s security against an unpredictable Cold War enemy, and their dreams to see the planet from a vantage point where no borders exist, drove them to rise above all the challenges. Today, they all exude a sense of humble pride in being selected for such a pioneering experimental program. Payton sums up the entire era of the air force’s long-held desire to put a military man in space as any good officer would and credits the work done by the team he was honored to serve with: “In that era, we were successful at getting shoulder to shoulder on getting the job done on each of the military flights that flew on the shuttle. I think a lot of that is due to the MSEs.”