14

On the Way to Disney World

This is really tough on the families. The career guys, most of the wives married test pilots, so they knew what they were getting into. You look at the PSs, and they married engineers, not this guy that’s going to go sit on 4 million pounds of explosives so they can light it!

Robert Cenker

At the RCA Astro Electronics division in East Windsor, New Jersey, Bob Cenker was shuffling through some mundane paperwork one afternoon in March 1985. He had just wrapped up his responsibilities managing the systems integration on the company’s Satcom K-2 communication satellite and was looking forward to a few months of downtime before taking on a new assignment with the fledgling space station program.

An accomplished aerospace engineer, Cenker had joined RCA almost thirteen years earlier and worked closely with NASA engineers and astronauts on the Satcom series of communications satellites. He even leveraged this experience in applying to be an astronaut himself on two occasions. Both times, for reasons unknown to him, he was rejected early in the process. For now, he would live his dreams vicariously through his NASA colleagues, watching the fruits of his labor soar into orbit aboard the space shuttle in a few months’ time.

As he shared with an audience at KSC in March 2015, “I enjoy being an engineer. I like to build things. But I need some fire and smoke in my life once in a while. I need a launch. So I’ve spent my career working on commercial communication satellites because we typically launch one every two, two and a half years. So every couple of years, I get an opportunity to do that.”

As he busied himself, the phone rang. “Bob Cenker,” he spoke quickly, as he pushed up his oversized glasses and immediately recognized the voice of the division’s vice president of engineering. “Hey, Bob, remember that payload specialist slot we talked about? Well, we got it approved. Are you still interested in flying?” Stunned, Cenker blurted out, “Gee, let me think about that—yes!” Rather than explaining further, the voice on the other end of the phone left him with a cliff-hanger. “Okay, I’ll get back to you” were his parting words as he hung up, leaving the bewildered engineer to wonder what exactly had just occurred.

“I was a wreck. I couldn’t work,” Cenker told the authors. Not yet fully comprehending the news, his mind spun with questions. He pushed aside the stack of reports on his desk, swiveled out of his chair, and marched up to the vice president’s office. There he found the vice president’s smiling secretary, who let on that she already knew why the young engineer was there. She sent him directly into the office, where it became immediately clear to Cenker how real the offer was. “Now what?” he asked his boss. “You can’t just lay this on me. How long is the line? Who do I kill to get to the front of the line?” he joked. The VP’s response shocked him once again. “But we haven’t picked your backup yet,” he told Cenker. “My backup? Are you telling me that as long as I pass the physical, I’m flying?” Cenker could barely contain himself. “Yeah,” the boss said.

It finally dawned on him that the next “fire and smoke” he might experience was going to be propelling a space shuttle that he would be sitting atop. His work on the space station would have to wait. Bob Cenker, the twice-denied astronaut hopeful, was going into space.

Growing up near Uniontown, Pennsylvania, Robert J. Cenker was always fascinated by anything that flew. As a young boy, he would nail pieces of wood together in the rough shape of an airplane and toss them into the air. Lacking any semblance of aerodynamic stability or control, they would come crashing down to Earth, leaving him to ponder why his glider didn’t fly. He later found that he had a good head for mathematics, and once he got settled on attending Pennsylvania State University, aerospace engineering seemed to suit his interests and abilities. This would, in his mind, fill one of the prerequisites to becoming an astronaut, the other being joining the military to become a jet pilot.

“I was not a genius, but I had good grades,” he recalled. Despite his natural abilities and burning desire to pursue an aerospace career, one subject stood in his way:

The general consensus was that the “aero” courses—the fluid dynamics, were the weed-out courses. They were going to separate the men from the boys in aerospace engineering. And I poo-pooed that. Not gonna be a problem. I can learn anything I set my mind to. I almost flunked! And it wasn’t for lack of effort—I actually felt badly for my professor because he spent a lot of time with me. The head of the aerospace engineering department had both of us in his office trying to explain what was going on that this guy was flunking an honors student. I came into the program as an honors student, and I literally got a D in the first course in aerodynamics. And God’s honest truth, I think the reason they passed me was because we all knew I was going into the space program and that spacecraft dynamics, orbital mechanics, which is what I would wind up doing for a career, had nothing to do with fluid dynamics.

Still drawn to the physical sensations of flight while at Penn State, Cenker spent his free time launching himself into the air by any means possible. He worked out on the pool’s diving boards and introduce himself to bouncing and flipping high above the gym’s trampolines, experiencing a precious few seconds of stomach butterfly–producing weightlessness. Cenker figured due to his imperfect eyesight that this was about as close to real flying as he would ever get, since the military would accept nothing less than twenty-twenty.

When graduation came in 1970, entry-level jobs for a young aerospace engineer were scarce. With his bulletin board wallpapered with rejection letters from all the big-name companies, Cenker eventually settled on a position with Westinghouse in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, designing nuclear reactors for the U.S. Navy. And he hated it. He spent a year in the job before he learned that with the coming space shuttle program, NASA might be looking for scientists and engineers for the astronaut corps. So he formulated another plan to make himself more attractive to the space agency when the time eventually came to apply. Since his eyesight would preclude him from becoming a military pilot, he figured that perhaps experience as a rear-seated flight officer or navigator might get him some time in the air, operating as an integral part of an aircrew.

Cenker took physicals for both the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Navy flight, but when he went to talk to the navy recruiter, he could sense that the military had other ideas for him, given his experience. While they would be willing to grant his first choice of aviation, he was reluctant to sign up.

The navy wanted me to sign a document that says, “Oh by the way, if you flunk out of flight school for any reason, we can put you anywhere we want to.” And I said, “No—hell no, that ain’t happening—this is not flying by any stretch of the imagination.” I’m thinking with a year of mechanical design in nuclear submarines? I know where they’re going to put me, and I don’t want to go there! Because I was realistic enough to know that you never know when something would come up that you wouldn’t make it in flight school.

With the option of joining the military now far less attractive and still desperate to get out of the Westinghouse job, Cenker accepted an apprenticeship with his old advisor at Penn State working on spacecraft dynamics and orbital mechanics. Cenker would earn his masters in aerospace engineering by 1973 and was again having difficulty finding a job appropriate for his skills. Commiserating with his professor one day, he was asked if he had looked at RCA. “RCA builds TV sets!” Cenker responded incredulously. “I’m going to go from nuclear reactors to TV sets?”

In fact, the Astro Electronics division of the RCA Company also built satellites, going all the way back to the TIROS 1 weather platform launched in April 1960. The division, based near Princeton, New Jersey, was in the process of developing and building Satcom 1, one of the world’s first geosynchronous communications satellites. The project would open a whole new business line for RCA as a satellite manufacturing and operating company. “And so the fact that I had no experience meant nothing, because nobody did,” remembers Cenker. “I interviewed for the position, I worked on Satcom 1, and as the Satcom series and commercial communication satellite business exploded, my career just got sucked along with it. I couldn’t have timed it any better.”

While a number of Satcoms had been launched on expendable launch vehicles, RCA had booked two Satcom spacecraft for launch aboard the space shuttle missions in 1985, reimbursing NASA for “launch services associated with” each payload. One of those services associated with launch was the accommodation of an RCA payload specialist. Ironically, of the potential justifications for having a company representative on board, none of them included any responsibilities associated with the RCA-built satellites.

RCA’s Advanced Technology Lab, the U.S. Air Force’s Rome Air Development Center, and RCA Astro had worked together on a new infrared camera. “They came up with this staring focal plane,” explains Cenker, “which you can now buy in your local camera shop, but it was brand new thirty-some years ago.” The concept was a great advance over the current state of the art, in which infrared imagery was taken by a scanning method. This required the scanner to be ratcheted back and forth repeatedly, and if one were looking for a transient event, it could easily be missed, depending on where the device was in its sweep.

The new device was extremely sensitive. “The staring focal planes that they had—and I think this is about a thousand by thousand pixels—typically you could only see a difference of one degree Celsius from pixel to pixel,” Cenker explained. “The one that the guys came up with would see one-tenth of a degree Celsius. When we played with it on the ground, if I held out my arm, you could see the blood vessels in my arm, because they were a different temperature than the rest of my arm. It was fascinating playing with it on the ground in training.” The objective of flying the infrared camera was to observe various phenomena in space such as aurora, volcanoes, zodiacal light, and the moon to evaluate what the new invention was capable of seeing.

RCA had designed and built the payload bay television cameras for the space shuttle, and the labs were able to package the infrared camera into the standard camera housing, which would occupy the aft starboard corner of the cargo hold during the mission. While the technology did have potential military applications, the results of the test were considered to be RCA’s proprietary information rather than anything classified. “At the time, any data that a NASA astronaut took was public information,” surmises Cenker. “RCA didn’t want this to be public information, so they wanted to send one of their engineers along to take the data.”

And so when RCA Americom—the division that would own and operate the Satcom K series satellites—signed the launch agreement with NASA, they included the provision for the payload specialist. And once the word got out, Cenker would make it abundantly clear to anyone who would listen that he was interested in the job. “I used to joke with RCA management—joke nothing—I used to tell them,” Cenker says with a chuckle, “if you guys were really serious about the space program, you’d be flying a payload specialist, and oh, by the way, I’ll go.” But unfortunately for him, RCA had already selected their man.

In December 1984 Cenker was sent to JSC to brief the flight crews on the Satcom satellites they would be deploying on their missions the following year. While there, he ran across another group of RCA employees, one of whom was a PhD physicist from the company’s Advanced Technology Laboratory. He introduced himself to Cenker as RCA’s designated payload specialist for the infrared camera. “Congratulations! I hate your guts!” Cenker retorted, only half kidding. Somewhat deflated by this introduction, he shared with his RCA peers that he had long dreamed of spaceflight, even confiding that he had applied to NASA without success. Before long, the awkward conversation concluded, leaving Cenker wondering how management could have overlooked him.

With the conclusion of his work on the systems integration on the latest Satcom, Cenker anticipated being transferred to work on RCA’s slice of the newly announced space station project. The company was awarded a work package to develop both a coorbiting platform—a free-flying vehicle that would provide experiment support free of the manned environment of the station—and a polar-orbiting platform to host civilian and defense payloads launching from the Vandenberg launch site in California.

Not long after the trip to Houston, RCA’s corporate headquarters placed an inquiry with the Americom division, asking about the pending flight of their company’s representative. Being far removed from the day-to-day operations, they were curious what his role was at Astro Electronics. The problem was, unbeknownst to the management, their payload specialist worked at the Advanced Technology Laboratory, not at Astro. “No” was the answer from the company’s leadership. “If RCA is flying somebody in space, that person has to work at the space center.” Cenker later learned that a simple solution was proposed—RCA offered to transfer the researcher into the Astro division for a year or two in order to satisfy this requirement. The researcher declined.

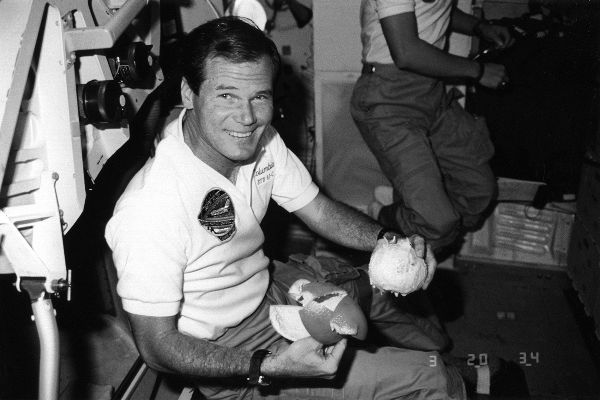

36. RCA’s payload specialist for STS-61C Bob Cenker. After applying to NASA’s astronaut corps twice and being turned down, he jumped at the chance to fly with the company’s Satcom satellite on the last mission before the Challenger disaster. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

“Obviously, it must not have meant too much to him,” assumes Cenker, “because if somebody had told me, ‘You’ve got to transfer to Timbuktu for two years, and you’ll fly on the shuttle,’ I’d say, ‘Where do I sign?’ And I’m gone.” Apparently, that one man’s decision opened the door for Cenker. In many ways, Cenker was the ideal candidate: “I was manager of systems engineering on the satellite that was deployed, so if anything went wrong with that spacecraft on deployment, I was the logical choice. Because I was in systems, I can understand the infrared camera. I can understand its workings. And we had already delivered the Satcom satellite. My work on that program was essentially done. But I hadn’t picked up any responsibilities yet on the space station, so if I disappeared for six months of training, nobody would know I was gone.”

From that unforgettable day in March 1985 when he marched into the vice president’s office and got the news, he became known throughout the company as the guy who was going to space. He could hardly believe the sequence of events that led him to a point in his life to realize his childhood dream. Once the company had announced his selection, along with fellow engineer Gerard (Jerry) Magilton as his backup, he would repeatedly be asked around Astro how he managed to be selected. On a few occasions, he would use the term “dumb luck.” But after a while, RCA management came to him and insisted, “Please don’t say dumb luck. We did not pull your name out of a hat! Say right place at the right time.”

Payload specialist Bob Cenker would happily oblige them.

Robert “Hoot” Gibson was one of the best pilots to have ever come to NASA. A former navy combat and test pilot, he excelled at everything he undertook and had fun doing it with an infectious sense of humor. His crew of Charles Bolden, Steve Hawley, George “Pinky” Nelson, and Franklin Chang-Diaz were an extremely tight, fun-loving team, despite coming from a wide variety of backgrounds. Hawley and Nelson were both astronomers; Bolden, the mission’s pilot, was a Marine Corps test pilot; and Chang-Diaz had earned a PhD in applied plasma physics. Gibson, Hawley, and Nelson each had one spaceflight under their belts, and Hawley had also been aboard Discovery when its engines shut down in the program’s first launch abort.

Easygoing as he was, Gibson had one firm rule, the infamous Hoot’s Law. As the seasoned navy pilot would instill into his crew, the law stated a simple observation based on his decades of flying air- and spacecraft—no matter how bad things are, one can always make them worse. “There are lots of ways that you can,” explains Gibson, “but one of the easiest traps to fall into is rushing.” He would impose strict cockpit discipline whenever a critical task needed to be accomplished, and if he were to throw a switch that might mean life or death, Gibson insisted that another crew member verified he had the correct switch first.

In addition to RCA’s Satcom K-1 satellite, NASA had originally manifested a Hughes Leasat spacecraft for deployment during the mission. Hughes engineer Greg Jarvis, who had previously been bumped from the STS-51D crew to accommodate Senator Jake Garn, would serve as payload specialist. Following unrelated failures of the two previous Leasats deployed from the space shuttle, the payload was removed from the mission, but NASA retained Jarvis on the crew to finally satisfy the Hughes launch agreement from the prior year. He would perform fluid-transfer experiments to test satellite fuel systems that his company was developing for future spacecraft.

Following a somewhat nerve-racking medical exam, both Cenker and Jerry Magilton settled into their training routine. “I think when I arrived, they gave me a stack of videotapes and books to read,” Cenker said, “because before we can start training, you have to have all of this background information before you’re smart enough to learn.” But there was never a lack of support from his NASA colleagues in learning the basics of flying aboard the orbiter. In his recollection, those in the Astronaut Office welcomed them as part of the team almost immediately: “I was amazed how well I was accepted. I fully expected there to be some level of bad feelings but didn’t find anything like that. You know they talked about the NASA family,” Cenker recalled, “most of whom would have given their right arm to fly, all of whom knew that I had literally walked in off the street and was flying. And I didn’t get one hint of resentment or hard feelings.”

In many ways, Cenker’s previous exposure to the people and facilities of JSC benefitted him as a trainee. Being an engineer from the satellite industry, he already understood many of the technical aspects of flying the mission, and his instructors found him to be highly qualified. “They told me that, if push came to shove, and they had somebody from within the space business, that they could probably train them in a month,” he shares. “Because you’re not learning to fly the orbiter, you have no vehicle responsibilities.” He still laughs today at the memory of a reporter from his hometown calling the space center to discuss his upcoming flight. When the writer asked what his training was going to consist of, the NASA spokesperson replied, “Well, we’re gonna teach him what not to touch.”

One afternoon not long after they began working together, Cenker and Greg Jarvis joined Hoot Gibson and the others for the traditional crew photograph. The five NASA astronauts and their payload specialists posed in the light-blue flight suits they would wear on launch day. But within just a few days of having the official photo taken, Gibson received a call from George Abbey to bring his crew across the JSC campus to his office in building 1.

When he closed the door behind them and sat down in front of the stone-faced director of flight crew operations, Abbey wasted no time getting to the issue. One of his crew members would not be flying aboard Columbia with them in December.

Jake Garn had set the precedent, with his flight aboard Discovery, that a congressional observer indeed had the right and privilege to fly aboard a NASA spacecraft. Often derided by the press and therefore the public as “the ultimate government junket,” these missions were not without their detractors both inside and outside the space agency. Don Fuqua, chairman of the House Science and Technology Committee, was notably outspoken against the practice of sending politicians aboard the shuttle. He had himself turned down an offer from NASA administrator James Beggs to fly, as he shared with NASA’s Bill Harwood: “I said, ‘Jim, I don’t want to go. Even if you told me I could go, I don’t want to go. And I’ll tell you why. I don’t think I have any business being there. This is still a very hostile environment. I’m not even sure you ought to have the Teacher in Space Program going. I don’t think I ought to bump somebody to go take a ride in space. I would love to! But I don’t think I have any business doing that.’” But once Garn had successfully navigated the media minefield in the run-up to his flight, others within the Capitol Hill hierarchy took notice and began to entertain their own desires to follow in his footsteps—in particular one junior congressman from Florida, Bill Nelson.

Nelson was a student at Melbourne High School in the fall of 1957 when the Soviet Union placed the tiny Sputnik satellite into orbit, and like most youth of the day, he followed the progress of the early space missions. Being just south of Cape Canaveral’s launchpads, Nelson watched firsthand as his hometown transformed into the center stage of a great new technological endeavor, yet he never saw himself destined to be part of it.

Nelson earned a law degree from the University of Virginia and joined the U.S. Army Reserves in 1965. He would serve two of his six years in the military on active duty and left the army in 1971 with the rank of captain. After practicing law in Melbourne, he was elected by his constituents to a seat in the U.S. Congress in 1978. His district included the Cape Canaveral peninsula and the surrounding communities populated largely by space industry workers, many remaining from the Apollo days. As NASA began painting the picture throughout the 1970s that the shuttle would open the new frontier of space to ordinary citizens from all walks of life, Nelson took notice.

He attended the launch of STS-1 in April 1981 and curiously read a report from James Beggs detailing the requirements for flying “observers” aboard the shuttle. At the time, it seemed a bit of a stretch to suggest that a politician would fit the description of a communicator, whose sole purpose would be to enhance the public’s understanding of manned spaceflight, but that did not deter Nelson.

The congressman rationalized that he indeed met all the basic requirements and set out to prepare himself as much as possible should the opportunity ever present itself. He exercised in the gym and ran daily. He devoured every source of information he could find on NASA’s programs and the space shuttle system. He leveraged his position in Congress to garner familiarization flights in high-performance jet fighters such as the F-15 and F-16, pulling as many blood-draining g-forces as he could stand. He wrote directly to Beggs, taking a gamble by overtly requesting a flight. But after two years with no response, the congressman thought better of pushing too hard and let things play out for a time.

Nelson was single-minded in his desire to accomplish what he could not even dream of growing up around the cape in the 1960s. As was the case with Jake Garn, it was well known around Washington that Nelson was pressing for a spaceflight. In early 1985 he challenged a senior congressman for the chairmanship of the Space Subcommittee and won. This did not only solidify his influence over the concerns of his home community; he also knew that only the respective House and Senate chairpersons were being considered for spaceflights.

Some in NASA leadership were dubious following some adverse public reaction over Garn’s flight and his less-than-satisfactory reaction in adapting to microgravity. Nevertheless, the space agency could not ignore the influence that potential congressional participants could have on the future promotion and funding of space activities. As the head of the powerful NASA oversight committee, Nelson was ideally placed in the budget-authorization world for Beggs to reconsider the benefits of granting him his chance to fly. The two would meet face-to-face a few months after Jake Garn flew in April 1985, and Beggs seemed to imply that a formal offer was not far off. In Nelson’s 1988 memoir, Mission, he shares the letter he received from the NASA administrator dated 6 September, reading in part, “Given your NASA oversight responsibilities, we think it appropriate that you consider an inspection tour and flight aboard the shuttle. While we will be flying quite often in the coming year, we will have to work out with you a mutually acceptable date. There will be a relatively short period of training which we can work out between your office and the Johnson Space Center to fit your schedule.”

Later that month, Nelson was already in Houston to undergo the same medical tests Cenker and Magilton had endured. He was sealed up in “the bag,” a pressurized fabric sphere that was, early in the program, presented as a rescue device for crew members stranded aboard a stricken orbiter. With a limited number of complete space suits on board, astronauts in shirtsleeves could be hauled across to a rescue shuttle for return to Earth, but the bag also proved to be a convenient test for claustrophobia. Nelson, sealed up in the warm, quiet sphere, happily drifted off to sleep.

The congressman would continue to split his time between Houston and Washington throughout his training. He had told NASA that given several important votes coming up, his preference would be to fly either on Columbia’s December mission or on Challenger’s January flight, STS-51L. Beggs wanted Nelson to have as much time to train as possible, so on 27 September he called and offered to have him fly on Challenger with schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe. Nelson accepted the decision of NASA’s leadership yet had confidence that he could be ready for the December flight. Behind the scenes, though, the decision makers at JSC had other concerns about flying the eager young politician.

37. Florida Representative Bill Nelson in “the bag,” a proposed rescue sphere intended to transfer crew members from a stricken orbiter to a rescue shuttle. Tolerating the close confines was one of many tests he needed to pass before being cleared for spaceflight. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

When Gibson and his crew were summoned to Abbey’s office, it quickly became apparent that the administrator had been overruled. The gruff astronaut boss informed them bluntly that they were going to take on Congressman Nelson and make the best of it. Greg Jarvis, with the Leasat satellite no longer aboard the mission, would be moved to STS-51L instead of the lawmaker. As Charlie Bolden shared in his NASA Oral History interview, “Mr. Abbey, in his infinite wisdom, decided that Hoot Gibson and his crew of merry men could better handle the congressman than most other people out there, so he switched us.” However, Cenker recalls that the decision, as it was explained to him at the time, was made for more than just his crew’s ability to accept Nelson into their fold:

McAuliffe was [assigned to STS-51L]. I think what happened was when they brought Bill on board, they had two non-aerospace professionals—Bill and the teacher. They had two aerospace engineers—me and Greg. Greg no longer has any attachment to 61C; there’s no Hughes spacecraft on board, so it doesn’t make any difference where he flies. On the other hand, if you flip-flop him and Bill Nelson, you would at least have Christa flying with another PS, but one that has an aerospace background, rather than having two total outsiders, and two reasonably well-trained individuals, being Greg and I, on the one flight and then those two on the other one. They just swapped those two around. It wasn’t like Greg was bumped for Bill Nelson; it was a logical choice, the way it turned out.

Nelson was back in Washington DC on 4 October when Jesse Moore, NASA’s head of the shuttle program, called to inform him that he would be flying aboard Columbia in December. Nelson took it on himself to place a call to his new commander and introduce himself, as Hoot Gibson recalled to NASA’s Sandra Johnson, “We are ‘yes sir-ing’ each other and ‘Mr. Congressman’ and ‘Mr. Commander.’” After a few minutes of this, Nelson asked formally if he could refer to him as “Hoot.” Once that was agreed on, Nelson insisted, “You must call me Bill.”

The congressman would continue to go out of his way to try to fit in with his NASA colleagues. More than anything, he really wanted to be considered “one of the boys.” George “Pinky” Nelson, who would take a major role in watching over him throughout his training, would regard him as “a model payload specialist,” being in better physical shape than many of them and displaying an eagerness to get in the middle of things and be helpful. Sometimes, though, his enthusiasm would get the best of him, and he might not have recognized the limits of his experience. Pinky Nelson remembers what he considered to be one of the most protective things he did for his same-name trainee—holding his two fellow mission specialists back from virtually strangling him.

“Every once in a while, when you’re inexperienced—he would just kind of get in the way,” Pinky recalled in his NASA Oral History interview. “And being the personality that Bill had, [he] wasn’t very good at getting himself out of being in the way, so there were times when you just had to kind of get him out of the way, and you had to be a little careful about how you did that.” Steve Hawley would usually lose his patience first and move in to relocate the rookie crew member, only to be restrained by Pinky or Franklin. “It’s just not worth it Steve!” Chang-Diaz would warn him. After a few weeks of training with the congressman, “It’s just not worth it Steve!” would be repeated many times over, to the laughter of everyone within earshot.

Bill Nelson found that the astronauts tended to keep their emotions to themselves, and discussions about personal beliefs or politics often took a back seat to technical issues. The inherent danger of flying in space had been long accepted by the professional astronauts who expected and even desired to take on multiple rides into orbit. They did, however, possess a wicked, sometimes even morbid, sense of humor, and Gibson’s crew stood out among their peers in this regard.

Given that he came to the crew so late in their training cycle and the fact that he had so little to offer the mission in terms of technical knowledge or operational experience, Bill Nelson got ribbed, hazed, and tormented by this court of jesters more than any other payload specialist who had come along. On the day Gibson was to take him up for a training flight in a T-38, the rest of the crew would put in bids for his personal effects should he not return. Even Nelson’s openness about his religious faith was not off-limits, and Gibson recalled a plan to fire a burst from one of the orbiter’s big thrusters in space and joke to Nelson that they’d just hit an angel. “We’d say, ‘Oh, Bill, don’t look; we just hit one. There’s feathers everywhere. It’s horrible, don’t look!’” Gibson laughed. Fortunately for Nelson, his crewmates never had a chance to hatch the plot.

Bob Cenker approached Gibson and the crew one day with an unusual request—he wanted to go on a second KC-135 zero-g flight. The Vomit Comet was not a favorite training event of many of the NASA astronauts, let alone the neophyte payload specialists, but Cenker loved it. It was the very thing he had dreamed about all those years ago on the diving boards and trampolines of his alma mater; only, the airplane did a better job of allowing him to float freely. His first flight aboard the jet had been cut short due to equipment malfunctions, and he only got thirty cycles of weightlessness, rather than the forty prescribed in the training syllabus.

“Oh yeah, Bob,” his commander said, “We’d like you to get to the point so you’re comfortable with that so that you all actually enjoy it!” Steve Hawley, who had been aboard that flight with Cenker, rolled his eyes and told Gibson, “If he had had any more fun, we would have had to have shot him to get him off the airplane!” And so it was that Cenker found himself aboard the old converted cargo plane once again, along with his backup Jerry Magilton, Bill Nelson, Greg Jarvis, and teacher-in-space selectees Christa McAuliffe and Barbara Morgan. Over the course of the flight, one of the most notable photos of this new age of “ordinary citizens” traveling into space was taken. Soaring through the long, padded cabin of the KC-135 that afternoon, five of the fledgling space flyers—two engineers, two teachers, and one congressman—all joined hands and flew in formation as the cameras caught their laughing, childlike faces in their new, weightless world.

As their training progressed, Bill Nelson took his oversight responsibilities as seriously as he took learning the mountain of new information being thrust his way daily. The congressman was constantly taking notes on various aspects of his training, the safety culture at the agency, and any concerns he could pry out of the tight-lipped professional astronauts. Always mindful of their desire to fly in space as many times as possible, he would occasionally find real issues behind their death-defying humor that they were afraid to bring forward. Other NASA people he came in contact with during their training would also express their opinions in subtle ways.

One of their training tasks was a firefighting drill. A silver-suited instructor ignited a large pool of jet fuel and told the crew he was going to show them how to walk through it. The firefighter gave Bill Nelson the hose and had him set it to “fog.” As Nelson would later share in his book Mission, “Instantly, a great cloud of fog spewed out in front of me, and I was able to walk right up to the blazing inferno without being scorched.” Then the instructor took things a step further, having the crew turn their hoses to a steady stream, parting the searing flames “just like the Red Sea was parted for Moses.”

The fire chief would explain to the crew how to sweep the stream of water back and forth to provide an escape path through the pool of flames. Wondering for a moment what he might be told to do next, Nelson was relieved when the instructor allowed them to back off without actually attempting the daredevil maneuver. When the exercise ended, he approached the silver-clad fireman and asked how effective such a procedure would be on the 195-foot level of the launch gantry, and he was met with a roll of the eyes from the chief. The congressman would come to suspect that many of the emergency drills the crew practiced would only be of use in an extremely benign contingency, not a catastrophic failure on the launchpad involving millions of pounds of volatile rocket fuels.

Nelson had also settled on an appropriate experiment to work on during the mission, a cancer research project sponsored by the University of Alabama. This payload would join a multitude of experiments aboard Columbia, including three that were part of NASA’s Shuttle Student Involvement Program. With the Leasat satellite removed from the manifest, the now nearly empty cargo bay was filled by a hodgepodge of experiments, including the second Materials Science Laboratory; a Hitchhiker payload; and thirteen getaway specials, all but one of which were mounted on a special bridge assembly spanning the aft end of the bay.

In the cabin of the orbiter, the astronauts would utilize an overhead window and attempt to photograph Halley’s Comet with a special camera as part of the CHAMP experiment. This would be the first of several flights of the Comet Halley Active Monitoring Program, an effort to obtain photographs and spectral data of the comet as it swung by Earth in its cyclical, seventy-five-year orbit of the sun.

Columbia’s flight, it was suggested, was something of a “year-end clearance” mission. In fact, as the preparations for the launch played out, there were real concerns that there was but one pressing need to fly it at all. “Here we are—we’re left with just one satellite, with the Materials Science Laboratory,” said Gibson. “[It] has been suggested that the reason we didn’t get canceled outright was because we had Congressman Nelson on board.” The RCA satellite could have easily been remanifested; and the various experiment payloads, spread among several future missions. At just minutes more than five scheduled flight days, it would be one of the program’s shortest nonmilitary missions.

Cenker returned to JSC after the November 1985 Thanksgiving holiday and found a surprise that really brought home the fact that he was about to go to space. The payload specialists had always been set aside in separate offices from the rest of the astronauts, but with the return of Atlantis after STS-61B, Cenker and his crew were now located together and afforded all the luxuries of being the prime crew for the upcoming mission: “The next flight up always took priority [for a] parking slot outside the Astronaut Office—there were seven slots. Whoever was flying next had priority, by definition. It didn’t make any difference—and PS—didn’t matter. When we went back after Thanksgiving, I had a new office, and I had a parking slot right in front of the astronaut building. I had arrived!”

As it would turn out, the astronauts of Columbia’s mission would be the next flight up for far longer than anyone could have anticipated.

Hoot Gibson and Charlie Bolden wanted to be anywhere but here—lying on their backs on Columbia’s flight deck bolted to a gigantic tank of explosive rocket fuel while lightning flashed all around the vehicle. “We climbed in, and I’ll never forget when I climbed into the commander’s seat on Columbia. . . . I’m looking up at the window,” recalled Gibson. “It’s raining so hard, and the tiles stick up about two inches around the window, so they form a dam. I’ve got a pool of water in my windshield.”

Bolden agreed, recalling to NASA’s Sandra Johnson, “It was the worst thunderstorm I’d ever been in. We were really not happy about being there, because you could hear stuff crackling in the headset.” They attempted to reassure their crew that the arrester system, an umbrella of cables strung out from the white mast atop of the launch tower, would prevent a direct hit on the external tank, but with every bright flash and thunderclap, their teeth clenched in anticipation.

This was the fourth time Gibson’s crew had climbed aboard the orbiter for a launch attempt. On 19 December 1985 a false reading on an SRB hydraulic power unit stopped the countdown just fourteen seconds prior to launch. With extensive repairs needed, NASA management decided to stand down through the Christmas holidays and tried again on 6 January 1986. This time, thousands of pounds of liquid oxygen was inadvertently drained from the external tank due to a procedural error.

The next day, the crew would again be stuck on the planet when poor weather at both of the transoceanic abort sites was below launch criteria. In a fortunate turn of events, this scrub allowed for the discovery of a broken temperature sensor lodged in the number 2 engine prevalve. It had likely found its way there during the defueling after the previous launch attempt. “That would have been a bad day,” recalled Bolden. “That would have been a catastrophic day, because the engine would have exploded had we launched.”

After hours of hoping that the fickle Florida weather would clear in time to launch Columbia on a stormy 10 January, the team decided to scrub yet again. For Cenker the closeout crew couldn’t get them out of there fast enough. “We had already aborted the launch, and so we got out of our seats, and we were sitting up on the backs of the seats,” he recalled. Pinky Nelson came down from the flight deck and lounged on the lavatory door. Suddenly, another clap of thunder shook the vehicle and filled the cabin with pure, white light. “You can come and get us anytime guys!” one of the crew members called out.

For the astronauts, though, the delays served to further bond them together. Bill Nelson, immediately following the first scrub, had returned to Washington, trying to make the transition, albeit temporarily, back to congressman. But following the Christmas break, he spent a majority of his time with the crew in Houston and Florida. In between January launch attempts, the astronauts spent hours in the KSC crew quarters watching classic comedies courtesy of Steve Hawley, as Gibson remembered: “He had Animal House. I had never seen Animal House until we started going down to the cape. [There was] Life of Brian, and it was The Holy Grail, those two Monty Python [movies]. He’s just a really funny guy.” After multiple viewings, it wasn’t unusual throughout their preparations to hear one crew member or another reciting lines from the films at opportune times.

The downtime also afforded an opportunity for the two payload specialists to approach some subjects with the experienced NASA astronauts that had, up to that point, been pushed to the background. During late-night conversations, Nelson and Cenker would pick the brains of the crewmates on some of the things that could go wrong and what the potential outcomes of these contingencies might be. The accidental opening of the orbiter hatch was brought forth, as was the failure of two main engines early in the ascent. Nelson gradually came to realize just how much of a calculated risk each launch was and the sheer number of catastrophic ways one could fail.

Cenker also clearly remembers a discussion that came up during the wait for the second launch attempt in early January in which the issue of flying payload specialists was broached:

We wound up in isolation over New Year’s Eve, between ’85 and ’86, and our spouses are gone, and we’re sitting there and drinking. . . . We had a few glasses of champagne or wine, and we were talking. The conversation came around to PSs versus career astronauts, and somebody asked the question, “What are you doing that we couldn’t do?” And it’s a perfectly legitimate question. And my answer—this goes back to the reason I believe RCA wanted someone to fly—I said, “With one exception, you can do anything I can. . . . I’m going back to RCA! Would you want to ride in a car that had been designed by somebody who had never even ridden in one? RCA wants somebody that’s been there, working on the spacecraft that are going to be a part of it. And that’s the real difference.” That was the only time the conversation ever came up, and they just sort of, “Mm, okay,” like that’s a perspective to think about. Nothing more was said. I don’t remember any response to that, positive or negative, but I never got a hint of any negativity while I was there.

Finally, after weeks of launch attempts and many more months of training and anticipation, 12 January dawned crystal clear and chilly. For the crew of Columbia, the wait was finally over.

People would often ask Hoot Gibson, “When you’re sitting there on the launchpad, are you scared? Are you nervous about something?” He typically answered, “Yes, I am nervous that something’s going to go wrong, and we’re not going to get to launch today. You’re on your way to Disney World. You don’t want to wait another day. You want to go now.”

“Disney World” lay two hundred miles above and an eight-and-a-half-minute rocket ride ahead for Columbia’s seven-man crew. As each astronaut waited to walk across the access arm into the White Room 195 feet above the launchpad, Bill Nelson, now for the fifth time, contemplated the hissing, creaking, black-and-white space plane standing on end in front of him. He stepped aside on the gantry and checked the right-leg pocket of his flight suit, ensuring that his pocket-sized Bible was not left behind. Kneeling down on one knee on the chilly steel grate floor, he silently bowed his head and said a prayer for his own safety and that of his crew.

Once he was strapped in on the middeck of the orbiter, Nelson glanced to his left just as Steve Hawley ducked his head in to check the progress of the payload specialists’ boarding. Nelson couldn’t contain a burst of laughter as he was greeted by a Groucho Marx–masked astronaut. Hawley, who now had more scrubs than anyone, joked that he didn’t want Columbia to recognize him, for fear of yet another cancellation.

The space shuttle stack vented streams of white vapor into the cold predawn air, bathed in blinding white columns of xenon light that stretched far into the sky above the pad. At T minus four minutes, the launch controller called for the crew to close and lock their visors. “When the visor comes down, it actually seats around that seal, and air comes from the shuttle’s air supply and inflates the inside seal, and it essentially isolates your skull from the sound,” Cenker explains. Bill Nelson pulled back the cuff of his glove, ready to punch his stopwatch at liftoff to keep up with the rapid sequence of events that was about to happen.

Gibson kept a running commentary for the benefit of his crewmates below deck, who had limited visibility into what was going on. “T minus ten . . . minus six . . . there go the engines.” The three main engines came to life and focused three blue shock diamonds of translucent flame into the Niagara-like torrent of sound-suppressing water cascading into the flame trench below. “When they light the main engines, you feel the noise for six seconds before they light the solids,” recalled Cenker.

As the two payload specialists craned their helmeted heads around to the left to peer through the orbiter hatch window, the solid rockets ignited. “Then you find out what noise is,” said Cenker. “I looked out that window, and I watched the gantry move. I didn’t know we were moving. If I hadn’t watched the gantry go by, all I felt was the noise. Now since I started hanging on the wall, as the vehicle turns over and flies downrange, I’m hanging from the ceiling. Now because you’re getting pressed into your seat, it doesn’t necessarily feel like you’re hanging upside down. I’ve got the seat belt and two shoulder straps on; you feel like you’re sliding up in your seat. It’s an interesting feeling.”

As the orbiter cleared the launch tower, control of the mission officially passed to JSC, and Gibson greeted them with a confident, “Houston, Columbia’s with you in the roll!” He could hear the cheers of the launch team over his headset, as the pent-up emotions of so many delays were finally vented with a tremendous roar. “Roger roll, Columbia,” came the response from CAPCOM Fred Gregory. Then all hell broke loose.

A series of alarms sounded in the cockpit. The most critical of the failures could have had dire consequences. Columbia’s commander would recall the ensuing events vividly even thirty years later: “We got a caution for helium usage on the center engine.” Gibson explained, “What it looks like to the computer and what it looks like to us is a leak. Each engine of the three main engines on the shuttle has its own helium supply bottle. We’ve got to have helium on those engines because the helium is a pressure barrier in the turbopumps between the hydrogen and the oxygen. You’ve got to keep them separated, or you’ve got a bomb. If the helium gets down to a certain pressure, [the computer is] going to shut that engine down.”

The simulator had shaken them but not like this. Bolden had every possible contingency checklist strategically Velcroed around the cockpit within easy reach should they be needed. Only, now his carefully arranged workspace was rocking so violently around him that he couldn’t read any of them. He desperately grasped for what he hoped was the correct card and tried to hold it close to his visor to dampen vibrations of the blurred checklist. Just then, he remembered . . . Hoot’s Law.

“There is nothing we can do right away, no matter how bad you think it is,” Gibson had instilled in him. “Let’s at least make sure there are two of us that agree on the procedure, and then we’re going to start working it. And we’re going to work it as a team.” Gibson and Bolden wrestled with the abnormality throughout the ride to orbit. All the while, Cenker and Nelson listened in as the flight deck crew calmly went through the procedure to isolate the potential leak, while Nelson kept track of their progress through the various abort points. The SRBs separated with a loud bang, and as they passed the seven-and-a-half-minute mark, the crew relaxed a bit, knowing that even with the loss of two engines, they could still abort successfully without ditching.

Bolden troubleshot the reported leak as a false indication, with little input from mission control. Things were happening so fast and this crew was so good that there was little they could add anyway. Gibson took pride in having such a sharp crew: “Those guys were so on top of everything that we couldn’t do anything wrong.” The final minute of the ascent pressed Columbia’s crew into their seats with a crushing 3 g’s. “You feel like you weigh five hundred pounds,” recalled Cenker. As the steady hum of the main engines fell silent, though, he immediately found himself weighing nothing at all.

The instantaneous transition to weightlessness was pleasantly shocking. Columbia had behaved like a vehicle on a shakedown flight during the climb to orbit, following a two-year refurbishment at its birthplace in Palmdale, California. One quick burn of the OMS engines had boosted the ship into an elliptical orbit, and another, longer burn would circularize it once on the other side of the planet. In the meantime, Bob Cenker would have one of the most memorable experiences of his life.

Hoot called out, “Okay guys, everything looked clean. If you want to get out of your seats, don’t start unpacking anything, because we still have to confirm everything, but if you want to just get your space legs, you can unstrap.” And I undid my seat belt and my harness and I came up out of my seat and I was holding on to the seat belt and I was looking down at the seat—and I can picture this like it was yesterday—thinking, “I’m not going to use that seat for the next five days. This is not a carnival ride; this is not twenty seconds of zero-g. I am in space.” And that was just bizarre.

Bill Nelson had his helmet off and his nose pressed up against the hatch window to get his first look at Earth from orbit. Marveling at the beauty of the curved, blue horizon, the congressman caught sight of a sparkling white object tumbling slowly away into the blackness of space—a small sliver of ice shed from someplace on the orbiter. As he watched, the sun set behind them as Columbia passed into the inky darkness of the nighttime hemisphere.

The crew had a lot of work to do configuring the cabin and preparing for the Satcom deployment, but it didn’t take long before Cenker noticed a strange sensation. No matter how he oriented himself, he felt like he was constantly upside down. The heart takes time to recognize that it is in zero gravity and typically keeps pumping the same volume of blood to the head as it does on Earth. This causes fullness in the head and, coupled with the visual cues his eyes were flashing to the brain, made Cenker feel as though his senses were in complete disagreement. “Flight day 1, I was not a happy camper,” he explained. “I didn’t get physically ill but had many of the symptoms of space adaptation.” At his KSC appearance in 2015, he expanded:

They suggested because I wasn’t happy and I didn’t like that feeling, “You might not want to look out the window because everything is upside down. The shuttle is actually flying upside down, so turn upside down in the cabin.” If I turned upside down in the cabin on flight day 1, I thought I was gonna die, because now all of my visual cues are telling me, “You’re upside down.” Now, there is no up or down in zero-g. Visually, it’s amazing how driven we are by what we see and what our perceptions are. It’s one of the things that they believe is a heavy part of the space adaptation process.

From Columbia’s 201-mile perch above the planet, the four-thousand-pound Satcom K-1 spacecraft would be boosted over 22,000 miles higher by the new, larger PAM D-2 rocket motor. Nine hours into the flight, the sunshade was retracted, and the glittering silver-and-gold box began spinning up to fifty revolutions per minute. Cenker took great pride watching the satellite he had shepherded through its birth push up out of the payload bay with an audible thump.

That pride was still evident decades later when he spoke of the satellite with the enthusiasm of a proud parent. “If you had the Primestar direct to your home TV between 1986 and 1998, it came to you courtesy of the Satcom K-1 spacecraft that was deployed on our flight. We had a design life of nine years, and one of my professional accomplishments, if you will, which involves a bit of luck to get anything like this to go longer than its design life—we went twelve years on this spacecraft.”

Bill Nelson struggled a bit getting his protein crystal growth experiment working in the middeck. Working with various proteins, including purine nucleoside phosphorylase, which held promise for cancer treatment, he had an extensive list of tasks to perform to get the gear operating. There were forty-eight chambers in which to mix the various chemical agents, followed by initial photography of the experiment. And all of this had to be done while Nelson was still adapting to space, where every activity seemed to take a lot longer than it did on the ground.

By the beginning of their first full day in space, both Cenker and Nelson felt well enough to start enjoying the experience of weightlessness, experimenting with various oddities the environment provided. Nelson took delight in tumbling slices of grapefruit into his mouth, a fruit he insisted on having aboard the mission that earlier had caused a small controversy. Being a Florida representative, he had specified that NASA pack grapefruit grown in his home state. Worried about the reaction of other states’ citrus growers to this partisan preference, the agency nixed the idea altogether. But Rita Rapp, NASA’s dietician who oversaw all the food selection for spaceflight, managed to get enough deidentified grapefruit aboard Columbia for Nelson to share with his crewmates. Nelson had no idea while he was in space that the public flap had not been easily forgotten by some other parties on Earth, and he had not heard the last of it.

38. Bill Nelson peels a grapefruit from an undisclosed state courtesy of NASA’s space food pioneer Rita Rapp. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

The flight plan for Columbia’s mission was packed with maneuvers to be performed by Gibson and Bolden for the benefit of two of the payloads aboard—the ultraviolet experiment (UVX) and the comet-observing CHAMP. UVX was contained in three of the getaway special cans on the bridge structure, two housing the ultraviolet telescopes and one housing the electronics. CHAMP was to be mounted in an overhead window in the cabin of the orbiter and operated directly by the crew.

Each of these astronomy experiments competed both for crew time and for vehicle attitude, as the orbiter’s payload bay had to be pointed at particular spots in the sky in order for the intended target to be observed. That competition ended abruptly on flight day 2 when Pinky Nelson set up CHAMP, only to find that it had been left powered on since it was loaded aboard Columbia; its batteries were dead. And nobody had thought to pack spare batteries. “Hawley’s Comet,” as the crew came to call the dirty snowball orbiting the sun, would remain unstudied until CHAMP could be flown again on another mission.

Meanwhile, mission managers on the ground had already been considering their options for recovering some of the lost time caused by the multiple launch delays. The decision was eventually made to shorten Columbia’s flight by one day in order to get ahead on processing for the next mission, given that the major objective of deploying Satcom was behind them. With one less day now available to work on all the diverse experiments, several activities had to be replanned. When not maneuvering to various targets in the sky for astronomical observations, the Materials Science Lab 2 required the orbiter to be in free drift to minimize vibrations on the delicate study of various molten materials. Two sets of furnaces mounted on a support structure in the payload bay would melt samples that would then be suspended by either acoustic or electromagnetic levitators. Once solidified, it was hoped the materials would exhibit more attractive properties than metals produced on the ground. Unfortunately, throughout the third flight day, both the electromagnetic levitator and one of the furnaces kept repeatedly powering down.

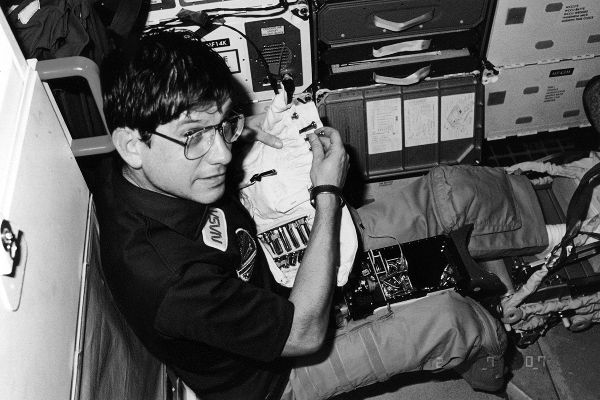

While the NASA crew members tended to their balky experiments, the payload specialists mainly worked in the middeck on a variety of medical supplementary objectives. Cenker took part in an experiment studying space adaptation syndrome. “This was a set of goggles that you actually strapped to your head,” he explained. “It measured your eyeballs’ motion while you were doing things, to try to understand how the mind changes its processing of visual data in zero-g.” This device, too, would experience a failure during the mission, putting Cenker’s engineering skills to work in an effort to repair it.

Bill Nelson continued to monitor his protein crystal growth experiment and assist with the medical tests as well. A man capable of deep observation and introspection, he would frequently pull his small tape recorder out of a pocket and find a quiet place to capture some of his thoughts. At one point, he would retreat to the air lock, where squeezed in between the empty, white space suits; he felt as if there were two astronauts behind the helmets listening in on his dictation.

When it came time for bed, Cenker had no problem at all getting to sleep: “I could sleep anywhere anytime, so I just literally stuck myself to these Velcro strips and fell asleep hanging on the wall.” There was one night when his fellow payload specialist had a little fun at his expense. “At some point in the night, I moved away from the wall, and I’m floating around the cabin,” Cenker recalled. In the continuous flow of air that circulated throughout the cabin, Cenker drifted slowly around in an arched, baby-in-the-womb slump, until he bumped up against a drowsy Bill Nelson. “Bill pushed me away, and the air pushed me back. And Bill pushed me away, and apparently this happened a couple of times,” laughed Cenker. After several interruptions, Nelson decided to put an end to this. He grabbed a nearby roll of duct tape and set about firmly securing his crewmate to a wall, where he would wake hours later struggling slightly to free himself.

39. Cenker puts his engineering and mechanical skills to work, attempting to repair a goggle-like biomedical experiment after it failed on orbit. Courtesy NASA/Retro Space Images.

On flight days 2 and 4, Cenker got to operate the payload he was primarily responsible for. From the aft window in the flight deck, he and Bolden would take turns maneuvering the camera housing in the payload bay to point the infrared device, recording video of auroras, volcanoes, and various cities as they orbited high above. “It was great. We got a lot of data,” Cenker shared. “We were trying to see what we could see with this particular camera. The question is, Okay, what can you tell? Who knows? You won’t know it until you try it, because nobody had done it before. So we took a lot of video, and that experiment worked very well.”

By 16 January, after barely four days in space, the crew was packed up for the trip home. With the payload bay doors closed and the cabin floors crowded with crew seats once again, all seven were outfitted in their launch and entry coveralls, harnesses, and helmets. However, the weather at KSC was not lending itself to the possibility of a space shuttle landing, with low clouds and rain showers. Just five minutes before the burn that would set Columbia on the irreversible path back to Earth, mission control waved them off. Not only would they regain the day lost due to NASA management’s decision to shorten the mission; they would end up setting another record—the number of delays in trying to bring a shuttle mission home.

Columbia’s crew would get very good at stowing the cabin for a landing attempt over the next two days. Backing out of all those preparations was a time-consuming and tedious task. The payload bay doors were reopened, and all of the orbiter’s systems were reconfigured for on-orbit operations. On the first wave-off, they decided to leave the seats installed and the air lock hatch closed to shorten their tasks up a bit. Having already been awake for over eight hours prior to the decision, Bill Nelson actually dozed off to sleep, floating upside down freely in the middeck.

With a few hours left before they were scheduled to prepare for a sleep period, Gibson radioed to mission control, asking if there was anything they could work on in the intervening hours. A few suggestions came up in response, but the final task took the crew by surprise. “Okay, we want to do another run of this . . . and another run of something, and CHAMP.” As Gibson remembers, “Charlie keyed the mike, and he started to say, ‘Okay, we copy.’ From downstairs on the middeck, as Charlie has got the mike keyed, Pinky and Stevie—when they had heard ‘CHAMP’—they spouted a line from . . . I guess it was Monty Python and Life of Brian. They both simultaneously from downstairs called out, ‘Aw, piss off!’ Charlie started laughing so hard he couldn’t finish his statement.”

Unfortunately for Bill Nelson, the shortened flight plan dictated that he deactivate his protein crystal growth gear a day earlier than planned. Now, rather than having additional days of microgravity to work with the experiment, he couldn’t restart it once it had been shut down. He would have to return to Earth with the samples he had and hope for the best. As he would learn after the conclusion of the mission, the experimental crystals he had seeded continued to grow on their own, even after he had stopped monitoring them.

The next day, the crew awoke to find their cabin virtually ready to return to Earth, given that they had done minimal unpacking. Their flight suits were splayed out neatly on the forward lockers, with their pockets full of the necessary items for the return home. But once again, it was not to be. The unpredictable weather at the coastal launch site on the Florida coast was still not acceptable to attempt landing. Cenker knew this had to be their last day in space—tomorrow they would be back home, be it in Florida or at Edwards Air Force Base in California. So he made the most of it. Cenker went to work on the infrared camera again. “Because the mission got extended that extra day, everything else had been packed up,” he explained. “So for that extra day, we had videotape. We got quite a bit of video of engine firings, thruster control engine firings, and scenes from the ground.”

Now six days into what was originally scheduled to be a five-day mission, Gibson’s crew was running short on many essential items. Bill Nelson’s grapefruit was depleted, as was much of the rest of their food. Steve Hawley would offer a glimpse into just how bad it was getting: “We had run out of most everything, including film, and part of our training had been to look for spiral eddies near the equator, because the theory was, for whatever reason, you didn’t see them near the equator, and Charlie was looking out the window and claimed to see one, and I told him, ‘Well, you’d better draw a picture of it, because we don’t have any film.’”

During one of their final television opportunities, the crew sent a special message down to Houston that had the flight controllers bewildered. When the camera was switched on, six of the crew members were all oriented vertically in the middeck, with Pinky Nelson floating horizontally across the foreground. But in the middle of the group was the unmistakable red-suited, white-bearded figure of Santa Claus! Small gift-wrapped boxes spun in the air in front of him as Gibson told them how surprised they were to get Christmas gifts so late. Gibson would later reveal just how the “jolly old elf” himself had managed to rendezvous with Columbia in space:

We were going to be in space, and we were going to land on Christmas Eve. We went and made up a video. We went into the mock-up in building 9. The seven of us and another astronaut dressed up in a Santa Claus suit made it look like we were weightless. We had a couple of presents that actually were hanging by black threads. We’d be spinning them, and they’d be spinning in midair. That astronaut was Sonny [Manley L.] Carter. He was our Santa Claus. So there were eight of us in the picture. We took that to space with us because we were going to land on Christmas Eve, so we were going to call and say, “Hey, we have a special visitor up here that dropped by to bring us some presents.” We actually wound up using it when we did go to space, because we went to all that work to make up that video. Nobody on the ground even realized that there were eight people in the video. They said, “Who was in the Santa Claus suit? Which one of you guys was in it?” We said, “Did you guys count noses in that picture? There were eight people in that video.” Nobody even noticed it.

“That’s a great video,” remembers Bob Cenker. “When the people on the ground first saw the video, they wondered how the hell we commandeered the KC-135 to get that kind of fidelity.” And the crew had one more surprise for the folks on the ground. Gibson, Hawley, and Pinky Nelson were the founding members of the all-astronaut band Max-Q, named for the period of maximum dynamic air pressure on the orbiter as it rocketed into orbit. Gibson rewrote the lyrics for the song “Where or When,” and when he keyed the mike again, the entire crew joined in for their own rendition of the song, lamenting their seemingly endless circling of the planet, to raucous applause from the flight controllers.

That night, on his final opportunity to enjoy the incomprehensible experience of spaceflight, Bob Cenker didn’t waste a single moment on sleep. Rather, he floated quietly at the overhead windows on the flight deck and took in the majesty of the earth below:

I stayed up all night and looked out the window. Went around the world five times. It just boggled the mind. I watched a thunderstorm over Africa, and it looked like I was watching popcorn in a popper. You could just see the clouds lighting up—almost like you could hear it, it was that intense. A sunrise and a sunset in space were just amazing. Imagine the most colorful sunset you have ever seen. Imagine flying through all of those colors in about five minutes, because that’s what’s happening, you’re flying through the sun’s light as its being bent by the Earth’s atmosphere. And I had told people if I could take my wife and family and move into space, I’d be gone tomorrow. That was the only part that was bad. Whenever I travel on business—when I was traveling to Houston, there was The Galleria—it was a big mall down there . . . “Barbara would love this place.” And you go by the Astrodome . . . “My son would love this place.” Whenever I travel on business, you make those connections. And that night I stayed up all night, I remember thinking, “I’m never going to bring anybody here,” and that was tough. That was tough.

Bill Nelson put on a good face, but he was having an especially difficult time readjusting to the crushing force of gravity, which, aside from the past week, he had lived his entire life with. Wobbling his way up into the transfer van, he found waiting for him a huge basket of oranges with a sign reading, “Congressman Nelson, welcome to the state of California. Enjoy a delicious California orange.” His insistence on having Florida citrus on board had become well known, and astronaut Dan Brandenstein arranged one last prank at his expense. Nelson was less than amused.

Just a few hours before, Columbia had come screaming over Los Angeles at Mach 3, rattling windows for miles around in the predawn darkness. The third opportunity to land back at KSC in Florida had once again been waved off due to the ever-changing coastal weather, and the time had come to bring the flight to an end at Edwards Air Force Base. Only the second time the shuttle had been landed at night, the move not only added days to the turnaround time for Columbia’s next flight but also ruined Nelson’s triumphant return to his home state.

Fortunately for the crew, Hoot Gibson had insisted that most of their simulated landings be practiced at night for just such a circumstance. Columbia once again showed its unique personality to the pilots during reentry, with a series of failures that kept them busy throughout the long glide home. After a ten-thousand-foot rollout on the concrete runway at Edwards, the crew took their time readapting to 1 g. As Cenker recollected, “We waited in the White Room for about twenty minutes to a half an hour to get your legs back. We’re okay coming down the stairs strengthwise, but if you should stumble, your mind’s not going to catch you automatically. Your mind thinks you’re going to float off into space. You need to hang on to something to give yourself a chance.”

Their mission complete, the payload specialists of STS-61C would go their separate ways. Cenker returned to RCA with the anticipation of bringing his spaceflight experience to the company’s work on the space station. Nelson returned to Congress, where he served until 1991. After several years away from the political scene, in 1995 he became treasurer, insurance commissioner, and fire marshal of Florida. In 2001 he once again returned to Washington, winning a Democratic Senate seat for Florida, where he continues to serve as of this writing. Just ten days after they stepped off their orbiter at Edwards, Challenger lifted off from launchpad 39B at Cape Canaveral on its ill-fated final flight.

Bob Cenker to this day has no idea what happened to the data from the infrared camera he operated aboard Columbia. It disappeared into the somewhat-secretive research lab side of RCA, and he never saw it again. “Somebody called me about looking for the hardware, because the hardware came back too, obviously, and they wanted to fly it on an expendable launch vehicle,” he shared. But that too was nowhere to be found. “So, there was interest in it, but it wasn’t really part of my engineering discipline. I operated it as a competent operator, I guess.”

Following the Challenger accident and the subsequent cancellation of shuttle launches from Vandenberg, RCA’s concept for a polar-orbiting platform was shelved. Even though there was a Satcom K-3 satellite coming down the line, Jerry Magilton lost any hope to fly his own mission for RCA with the removal of commercial payloads from the shuttle. “We didn’t know which way RCA might go,” Cenker explained, “whether they would fly the same guy twice, whether they would start with a whole new pair. He and I talked about it, and certainly he wanted to fly. But we never had any insight. And basically, quite frankly, it wouldn’t surprise me if RCA hadn’t contemplated beyond that one.”

Cenker would go on to work on many other satellite projects for what became GE Astrospace, and for several years prior to his leaving the company in 1990, he was the manager of payload accommodations for the company’s contribution to the space agency’s new direction. “[NASA] had started the Mission to Planet Earth,” he reflected. “So they just resurrected all of that old stuff and called it the Earth Observation System, the EOS platform. And I was payload accommodations because originally I had been part of the station program that was going to run those spacecraft.”

Since leaving GE, Cenker has continued to consult with a range of aerospace companies, often leveraging his spaceflight experience yet still reluctant to refer to himself as an astronaut. He occasionally does public appearances in front of large audiences and seems quite comfortable in the role, sharing his story of a single flight to space over three decades ago. “I often refer to myself as a payload specialist astronaut,” he says. And to children and young adults in the audience who line up for photos and autographs, the qualifier doesn’t seem to matter in the least.

When attending functions such as the Association of Space Explorers meetings, however, he is keenly aware of the feelings of some of his fellow space travelers:

I know there are still those with some resentment or questioning, if you will, the qualifications of those of us who did not help fly the vehicle but were merely passengers. And there are many guys who are quite comfortable with it. Some of the old guys treat us like we’re one of them, no questions asked. But then you’ll hear rumblings from other people, “Well, he’s not an ‘RA’—a real astronaut.” It doesn’t really matter to me because I got to fly. It was a dream come true. I’ve done something that the vast, vast, vast majority of the world can only dream about.

He certainly would never hear anything of the sort from his old crewmates. The astronauts of Columbia’s mission have remained exceptionally close over the years, having several reunions and other get-togethers. “We have been dear friends,” Hoot Gibson candidly admits today. “We all dearly love each other.” Having flown five times with astronauts and cosmonauts from all over the world, he still considers these men “by far the closest crew that I’ve ever been with, trained with, and kept up with over all these years.”

Today, they often cross paths with the man Gibson now has to address as “Senator Nelson” in more formal settings. Nelson has continued to be a staunch supporter of NASA’s programs, even throughout the contentious years of the Constellation lunar program’s cancellation, the formulation of new national space goals, and the development of the Space Launch System. Charlie Bolden was named NASA administrator in 2009, and both he and his former commander have been called to testify on numerous occasions in front of the committee chaired by Nelson. Neither Gibson nor Bolden would pass up an opportunity to help shape an endeavor they so passionately believe in and want to see flourish.

Nelson has always favored an inspirational quote that hung on his office wall for years and sums up his motivations perfectly. Harkening back to the risks he took to step aboard a space shuttle in 1986, he sometimes concludes spaceflight-themed speeches with the words of Helen Keller. “Life,” it reads, “is either a daring adventure or nothing at all.”