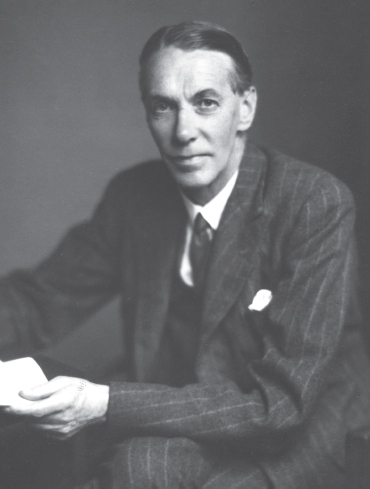

WHEN HUBERT HENDERSON first came to All Souls in 1934 he was not known to many of its fellows. D. H. Macgregor, the Drummond Professor, who, like Henderson, had come from Cambridge, had, I think, some acquaintance with him; R. H. (later Lord) Brand and Sir Arthur Salter knew him well, and one or two of the relatively senior fellows had come into contact with him in the course of his public activities. But to the majority of the junior and academical fellows who formed the bulk of the College he was virtually unknown. He appeared gentle, shy and a trifle vague. He was courteous, amiable, but reserved; and seemed a little bewildered. All Souls was, and still is, sui generis, and the effect it will have upon those who come to it in middle life is difficult to foretell. Henderson had been deeply involved in public life both as editor of the Nation and as joint secretary of the Economic Advisory Council. All Souls must have seemed to him a curious private world, exceedingly unlike either Cambridge or the larger world which he had inhabited.

It took him a little time to assimilate, but when he did so he came to occupy a distinguished and unique position in the College. He liked conversation; he was interested in many topics and was glad to speak about them with anyone who responded to his own detached, disinterested and essentially middle-road notions; he did not particularly expect or take pleasure in agreement. He was a man of deep convictions, which he held with clarity and a kind of tranquil passion; in argument he was eloquent, lucid and tenacious; and since he was free from solemnity and priggishness, and liked to discuss whatever interested him, he took equal pleasure in analysing personalities and in dissecting abstract topics or political issues, and treated them always in the same scrupulous, and sometimes animated, fashion. He talked well, and with a courtesy of manner which never abandoned him even in moments of acute provocation; nor were either his juniors or his seniors ever made to feel that he put them into any category or box, or that he was conscious of being in one himself. This made the experience of talking with him, whether à deux or in company, particularly delightful and profitable. Nobody, I think, felt about him that he belonged specially to any one section of the College, of the senior fellows, or of the junior fellows, or of academics or of ‘Londoners’, or of conservatives or of progressives. He had a genuinely independent personality, and held sharp ideas and opinions both about persons and about issues, and spoke about them without rancour, without self-consciousness, moderate in judgement, intellectually intense, and naturally civil.

I dwell upon the quality of his talk because All Souls has been, as long as anyone remembers, a college of talkers, and his own genuine love of conversation and debate caused him to fit into it without effort. He liked to talk an issue through and he liked argument; he wished to make his own views entirely clear to others and to grasp theirs as fairly and as accurately as he could; and since he had an intellect of exceptional acuteness and integrity, and a genuine desire to establish the truth, and sincerely believed that this could sometimes be done by means of rational discussion, he used to argue on and on, with tenacity and absorption, and infectious spontaneity. His face would assume a puzzled, sometimes bewildered or incredulous, expression when, as occasionally happened, his opponent seemed to him to advance opinions which no sane or well-informed person could conceivably hold. He would ruffle his hair, his voice would rise in pitch, he would make gestures of despair, but, whatever the hour, he would go on. He would never willingly let go. He would never grow angry, or rude, or waspish, no matter how maddening his opponent seemed to him to be. The hour would grow late, it would be past midnight, and the ashtray beside him would become filled and overfilled with the stubs of du Maurier cigarettes. If, as sometimes happened, the argument broke down under a hail of mere counter-assertions, he would simply grow silent and avert his thoughts; if the tone grew too sharp he would look at a newspaper or quietly leave the room. He was not at his ease save in an atmosphere of courtesy, intelligence, moderation and a modicum of intellectual goodwill.

He had an acute sense of humour, and, in particular, of the ridiculous, which found free play in Oxford, together with a boyish sweetness of disposition, and a genuine hatred of all forms of sentimentality and humbug. For those younger than himself (of whom alone I can speak with confidence) he was easier to be with than almost any other of their seniors: he was not in the least pompous, not in the least vain, not in the least difficult; he had an open mind and a natural fund of sympathy and kindness. He treated all men as equals, and contact with him was direct and delightful. One was never reminded, by some unconscious phrase on his part, of his own eminence in the world of affairs, or of particular convictions or prejudices which it was not safe to touch upon. He liked to be amused, he was not censorious or disapproving of high spirits or gaiety or even of a degree of silliness and nonsense in others, and he was not put off by eccentricity; in short, he was in favour of the flow of life, he enhanced it, and was a cause of it in others. What he liked above all was a combination of imaginative ideas and practical knowledge, and at All Souls he found these in sufficient quantity. On committees his good judgement, freedom from bias, clear principles, fearlessness and unruffled good temper (the high falsetto to which his voice rose in moments of excitement sometimes belied him) were a great asset, particularly at moments when these qualities seemed to be on the ebb; at college meetings he spoke with authority. All Souls is a large college, and to be effective at its meetings one must have a certain degree of oratorical power. This Henderson did not possess, but his speeches were listened to with respect because his impartiality and independence were evident and because he was widely liked and admired. I doubt whether he knew how widespread this feeling was until he was elected Warden: he was not a man who spent time on reflecting about other people’s attitudes or feelings towards him; this went with his freedom from vanity and neurotic preoccupation with his own personality or status. He had, to everyone’s sorrow, had a breakdown in health during the last war, but had seemed to make a complete recovery and continued to play his part in College, as a member of committees, and as a frequent assistant examiner in economics in the fellowship elections. His shrewd judgement as an examiner was always much trusted and has vindicated itself, so far as I remember, on all occasions.

After the untimely death of Warden Sumner in 1951 he was elected to succeed him in June of that year. He certainly did not seek the office. If ever there was a popular ‘draft’ of a reluctant candidate, this was an instance of it; for a long time he did not wish to be considered, and when in the end he allowed himself to be discussed, it was due not to ambition, nor even to a sense of duty (for I am sure he did not consider it anyone’s particular duty to seek or hold such office), but because it was part of his inherent modesty not to resist too violently the pressure of his friends. I doubt if he asked himself whether he had much chance of being elected; I am sure that he did not care in the least how great or small it was. I remember very well his air after his election, which was, as so often in moments of crisis, slightly bewildered and incredulous; he was deeply moved by this token of corporate trust and affection.

He scarcely entered upon his reign. A few days after his election he had a heart attack in the Sheldonian Theatre, on the day of the Encaenia. I went to visit him at the Acland Nursing Home and he was, as always, charming and cheerful; with, as the Vice-Chancellor so well said of him in his commemorative remarks, ‘his quiet gaiety and his transparent goodness’.1 To goodness he added purity of character, distinction of intellect and of feeling, a sense of public duty, and a devotion to personal relations and private life, as well as, beneath his vagueness and gentleness, a foundation of Scottish granite which gave him an unsuspected strength of will. He possessed a blend of characteristics which All Souls, in the view of some, should aim at producing: he was intellectual – he was interested in general ideas – but he was neither woolly-minded nor pedantic, nor locked in an ivory tower. He was involved in public affairs, and took a lifelong interest in public issues, but he was not a philistine and did not judge an academic world by the standards drawn from public life, or vice versa. He admired practical good sense and administrative ability, and respected all experts and métiers as such, and was very suspicious of abstractions and theories in his own subject, which he regarded as essentially applied and not ‘pure’. On the other hand, he was not militantly anti-intellectual; he liked any evidence of mental power or elegance; and suffered from neither of those two notorious occupational ‘complexes’ of dons – a repressed yearning for spectacular worldly success and influence, and a resentful odium academicum of those who aspire to it.

His attitude to the great world was balanced and harmonious. He was little worried by official reputations and liked associating with anyone whom he regarded as intelligent, enjoyable or interesting; and of these qualities he was a very good judge. He avoided fools and bores but gave even them little reason for offence. He liked thinking for its own sake and had a streak of imaginative poetry which used to emerge when, in the intimacy of sympathetic company, he would describe old friends or episodes in his Cambridge or London life. His behaviour was always wonderfully normal; there were no antics, no idiosyncrasies, no virtuoso flights, no conscious exercise of charm, no display; yet he felt neither jealousy of such behaviour nor disapproval. He did not resent or dislike cleverness or temperament in others, nor did he resent dimness or pedantry. But he disliked histrionic exhibitions, and every form of hollowness and falsity; he liked the dry and not the wet, the clear and not the obscure, however rich and suggestive. When an occasion presented itself, he took obvious pleasure in torpedoing arguments or schemes which appeared to him foolish or pretentious. He had an acute, ironical humour, was obstinate under attack, and could not be either snubbed or bullied. Ambition he did not seem to me to have, but he had much dignity and a proper sense of his own worth which was never obtruded, but emitted quiet radiations of its own. He did not speak unless he had something to say, and because he often had, talked a great deal, and because he had no fondness for small talk, was also often silent. His mind was just, acute and liberal, free from all personal and social prejudice, distinguished, serious, humane; above all, he was an exceptionally nice man, who remained detached from the normal academic categories, an independent human being on his own; and his premature death was a very great loss to his College and to his University.

1 [Maurice Bowra], ‘Oration by the Vice-Chancellor’, Oxford University Gazette 83 (1952–3), 85–7 at 85.