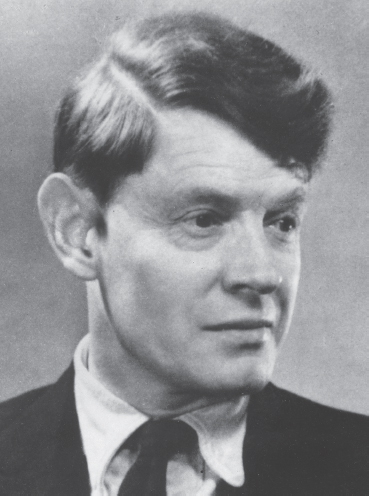

WHEN I FIRST knew Richard Pares, in the early 1930s, he was an unmarried research fellow of All Souls, and lived an ordered life, governed by strict self-imposed rules, dedicated to teaching and to scholarship. He looked much younger than his years, like a shy, distinguished, clever undergraduate; this alert and youthful look he retained to the end of his life. His intellect, clear, formidable and with a fine cutting edge, left no one in doubt of its elegance and power. With this he possessed charm of manner, a discriminating (at times almost feminine) love for whatever possessed style and form, and an ironical humour which alternately delighted and alarmed his more impressionable colleagues. He lived behind doors through which none but his intimate friends were permitted to enter; but his gifts, his distinction both as a scholar and as a human being, still more his uncompromising moral and intellectual principles, and his originality and strength of character, made him a natural leader of the younger, reforming party in All Souls. His moral influence upon his colleagues was very great. He talked very well: and his ascendancy was in part founded on his talent as a college orator. Few who heard it will forget the blend of original thought, caustic wit and controlled passion, expressed in apt and classically lucid sentences, that more than once altered the tone and direction of a college debate.

I remember no one, old or young, who failed to respect his intelligence, his unsleeping integrity, or the combination of piety towards traditions and institutions with his own independent judgement which he brought to the defence of whatever he deeply believed in – historical scholarship, the sanctity of personal relations, the maintenance of rigorous standards in the College or the University. Yet, with all his pride, his talent, his fastidious intellect and temper, he was kind, affectionate and gay. His moral feelings, which he did not trouble to conceal, did not make him censorious or priggish; they were allied to his deep and critical aesthetic sense. He chose the eighteenth century as his field of historical study, partly because he was attracted by order and formal beauty (he later occasionally complained that the human beings he found in it proved more brutal, coarse, bleak and repulsive than he had conceived possible). He read and reread Jane Austen, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf; he adored Mozart, and this aesthetic sensibility and understanding entered into all his relationships.

With all this, he belonged to the central stream of Winchester and still more of Balliol: he had a tender social conscience; he respected earnestness and public spirit; he was very just; he was a willing and lifelong slave of self-imposed obligations; and in consequence wore himself out by his devotion to research, his pupils, and later his service to the State. But he was not dulled by this stern self-discipline; he liked to be amused and exhilarated; he delighted in every form of artistic and intellectual virtuosity. As is sometimes the case with delicate and slightly wintry natures, he needed, and was sustained by, the greater vitality of others, and rewarded it with grateful and lasting affection. He had a keen sense of pleasure, and, despite his Wykehamical piety towards established values and his careful judgement and sense of measure, he welcomed eagerly almost any kind of original gift, however extravagant or eccentric, if it raised his own at times somewhat melancholy spirits.

But he did not, I think, count on such moments; when they occurred, they were for him a kind of windfall; he did not hope for much. To his mediocre pupils, he remained a conscientious, acute, sympathetic and stimulating tutor. He never allowed himself to intimidate or pillory the weaker among them, or to ignore them, or treat them with disdain. He disliked only the idle and fraudulent. But to those among them who displayed exceptional gifts he responded beyond their expectations: they found the most sensitive understanding and wide encouragement to the freest play of their imagination. Imagination, but not ideas. His distaste for philosophy, which he acquired as an undergraduate reading for Greats, developed into distrust of all general ideas. He disliked speculation and preoccupation with questions capable of no clear answers. There was always a predictable limit beyond which he declined to move. His values were fixed by the good sense and the authority of the moral and social order in which he consciously believed. Attempts to raise fundamental issues, whether personal or historical, were stopped with a few dry words, and, if pressed, with growing impatience and even irritation.

He was perhaps the most admired and looked up to of the Oxford teachers of his generation. He was attached to his pupils, and followed their subsequent careers with sympathy. But he avoided intimacy and kept himself apart, surrounded by a reserve that few dared to violate. He did not seek to dominate, to form a school, to bask in the easily acquired worship of undergraduates. In the outer field of political or social views he was prepared to be influenced; in the inner citadel of personal life and scholarship he remained self-sufficient, untouched and proudly independent.

He had, in a full sense, belonged to the great decade that followed the First World War. When he was an undergraduate of Balliol he became a close friend of Francis Urquhart and a member of the celebrated group that met in his rooms in Balliol and in his Alpine chalet. In particular Humphrey Sumner, Roger Mynors, Tom Boase, Christopher Cox, John Maud became his friends. And Sligger’s own disciplined life, his deep convictions and tolerance of others, made a lasting impression on him. At the same time he was on terms of intimacy with the leading beaux esprits of his generation: Cyril Connolly, Evelyn Waugh, John Sutro were his close friends, and indeed formed a society in his honour; and although he subsequently, by an act of will, turned away from these companions of his youth, to make himself an austere and dedicated scholar, his taste remained incurably and admirably sophisticated to the end of his days. He renounced what he had admired, even though he continued to admire what he had renounced. He fostered thoroughness, application, the disinterested pursuit of the truth; he told himself that there were no a priori reasons for supposing that the truth, when discovered, would necessarily prove interesting. He defended the duller virtues: he had always detested romantic rhetoric, ostentation, journalism. This became, to the point of pedantry, his conviction and his doctrine, but he was never solemn, was capable of moments of marvellous gaiety and high spirits, and had a strain of childlike innocence and fancy that went oddly but delightfully with the cultivated quality of his taste and intellect.

His lifelong belief in academic life and academic values was the faith of a convert; he wanted no recognition or reward outside its bounds. He was endowed by nature with a wide and generous vision, was very imaginative, and understood almost everything; it was therefore a deliberate self-narrowing – an act of self-imposed stoicism – by which he chose the life of a don, and adhered to it to the exclusion of many other interests. Universities were his home and his world. He was an excellent civil servant during the war; there, too, his colleagues regarded him with deep respect, admiration, and a liking not unmixed with awe. But he returned to academic life with relief. His professorial lectures at Edinburgh were, as always, fresh, first-hand, just; he earned the love and admiration of his pupils and colleagues there as everywhere. But when All Souls offered him the most distinguished research fellowship at its disposal, he resigned the professorship which his progressive paralysis made it hard for him to carry, and came back gladly. His academic distinctions – the fellowship of the British Academy, the Ford Lectures, the honorary fellowship of Balliol – gave him abiding pleasure. He was most happily married and delighted in his daughters. He took as full a part in the life of All Souls as his physical condition made possible. From his wheelchair he made pungent and effective speeches at College meetings, and carried all his old authority. His conversation was as clever and delightful as ever.

Great learning, tireless labours, unswerving pursuit of truth, even brilliant powers of exposition are qualities, if not frequently, yet sufficiently often found in combination not to constitute a unique claim. What was astonishing in Pares was the union of extreme refinement of mind and heart, an intellect of the first order, and rigorous self-discipline with acute perceptiveness and understanding of others, rare personal charm, an unflagging ironical pleasure in the comedy of life, and a disposition to gay and brilliant play of the imagination characteristic of a certain type of artistic genius. And with all this a sense of honour, greatness of soul, an unsullied purity of character, and a capacity for love and devotion which made his moral personality unique, and his example and his influence dominant in his generation.

Until the end he took a conscientious interest in public issues, but they were not central in his life. He was – so far as he had clear-cut political views – a moderate socialist, somewhat right of centre; but his heart was not in politics. He lived his life within the frontiers of a deliberately circumscribed world, a formal garden which he could shape according to his own desire for order and unity, harmonious and enclosed: a universe that consisted of historical study, of personal relations, and of his own full inner life. In this private world – perhaps the final flowering of Winchester and the Balliol of the 1920s – everything had its place, its own private name, its own particular relationship to himself. It was not an attempt on his part to protect his life against the chaos of the public world: within this hortus inclusus he demarcated carefully the realm of objective truth from that of his own sensibility and fancy.

His full height became revealed in the last year of his life, when he gradually lost control of his body, limb by limb, muscle by muscle, and, tended by, as he himself had called it, the loving-kindness of his wife, and by his children, he faced his end, which he knew to be near, with a noble serenity which no words of mine are fit to describe. He had not always been, but he died, a believing Christian. He was the best and most admirable man I have ever known.