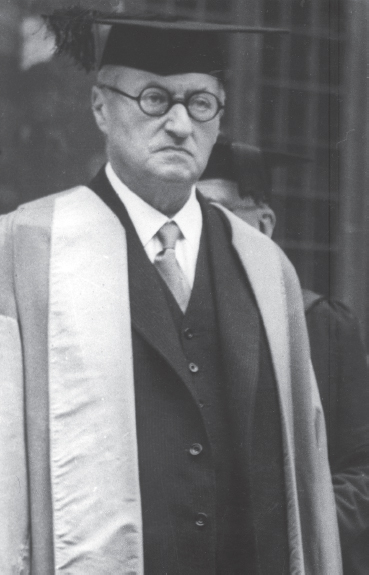

THIS ACCOUNT OF LEWIS NAMIER is based upon no research and is composed purely from memory. Namier was one of the most distinguished historians of our time, a man of fame and influence. His achievement as a historian, still more his decisive influence on English historical research and writing, as well as his extraordinary life, deserve full and detailed study. For this task I am not qualified. My sole purpose is to describe to the best of my ability the character and some of the opinions of one of the most remarkable men that I have ever known. I was not at any time one of his intimate friends; but his immediate intellectual and moral impact was such that even those who, like myself, met him infrequently but regularly, and spoke with him, or rather were addressed by him, on matters in which he was interested, are unlikely to forget it. It is this impression that I should like to record for the benefit of those who did not know him and may be curious about the kind of man that he was.

I first came across his name as an undergraduate at Oxford, in, I think, 1929. Someone showed me an article by him in the New Statesman on the condition of the Jews of modern Europe.1 It was the best and most arresting piece on that subject that I or, I suspect, anyone had ever read. Much was being written on that topic then; for the most part it was competent journalism: a combination of intellectual power, historical sweep and capacity for writing clear and vigorous prose was seldom, if ever, to be found among the writers on this subject, whether Jews or Christians. This essay was of an altogether higher quality. In reading it one had the sensation – for which there is no substitute – of suddenly sailing in first-class waters. Namier compared the Jews of Eastern Europe to a glacier, part of which remained frozen; part of which had evaporated under the influence of the rays of the Enlightenment; while the rest had melted and formed violent nationalist or socialist-nationalist torrents. He developed this thesis with incomparable imagination and a power of incisive historical generalisation that was at once factually concrete and had great historical sweep, with no attempt to play down disturbing implications. I wondered who the author might be. I was told that he was a historian whose work had caused some stir in the world of learning, at most a respected specialist, but not a scholar of the same order as Tout or Barker or Fisher, not to speak of Halévy or Trevelyan. That was that: the author was a minor historical expert with a fairly high reputation in his own profession. I heard no more until 1932, when I was elected to All Souls.

There I found that a higher opinion of Namier was entertained by my new historical colleagues – G. N. Clark, Richard Pares, A. L. Rowse and others. From them I learnt something of Namier’s real achievement. My election to All Souls had evidently intrigued Namier, who had failed to secure election himself some years before the First World War.1 I received a note in which, in huge majuscule letters, the author informed me that he proposed to call on me one afternoon in the following week and hoped that I would be free to receive him. The letter was signed ‘L. B. Namier’. When he arrived, he said in his slow, deliberate, ponderous voice that he wished to see me because his friend Richard Pares had told him that I was interested in Karl Marx, of whom he held a low opinion. He wished to know why I was engaged in writing a book about him. He had some respect for the fellows of All Souls. He believed them, for the most part, with certain exceptions which he did not wish to mention, to be intellectually qualified to do genuine research work. Marx appeared to him unworthy of such attention: he was a poor historian and a poor economist, blinded by hatred. Why was I not writing about Freud? Freud’s importance for historical and biographical science had still been insufficiently appreciated. Freud’s books were, unlike those of Marx, works of genius, and far better written. Besides which, Freud was still alive and could be interviewed. Marx, fortunately, was not; his followers, especially in Russia, which was now intellectually dead, had used up far too much printer’s ink, and were comparable in this respect with German philosophers, who suffered from an equal lack of sense of proportion and of literary talent and taste.

He stood in the middle of my room and spoke his words in a slow, somewhat hypnotic voice, with great emphasis and in a continuous unbroken drone, with few intervals between the sentences, a strongly Central European accent and a frozen expression. He kept his eyes immovably upon me, frowning now and then, and producing (I realised later that this was how he drew his breath without seeming to do so) a curious mooing sound which blocked the gaps between his sentences and made interruption literally impossible. Not that I dreamt of interrupting: the entire phenomenon was too strange, the intensity of the utterance too great; I felt that I was being eyed by a stern and heavy headmaster who knew precisely what I was at, disapproved, and was determined to set me right and to get his instructions obeyed. Finally he stopped and glared in silence. I begged him to sit down. He did so, and went on glaring. I made a halting defence of what I was, in fact, doing. He scarcely listened. ‘Marx! Marx!’ he kept intoning, ‘a typical Jewish half-charlatan, who got hold of quite a good idea and then ran it to death just to spite the Gentiles.’ I asked whether Marx’s origin seemed to him relevant to his views. This turned out to be the stimulus that he needed to plunge into his own autobiography. The next two hours were full of interest. He spoke almost continuously.

He told me that he was born the son of a man called Bernstein (or Bernsztajn), the Jewish administrator of a large Polish estate, and that his father had been converted to the Roman Catholic faith, which, he said, was common enough in his family’s class and circumstances. He had himself been given the education of a young Polish squire, for his parents believed that assimilation to a Polish Catholic pattern was a feasible and desirable process if one wanted it strongly enough. They supposed that the only barrier between Jews and Gentiles was the difference of religion, that if this were abolished, the social and cultural obstacles which it had historically brought about would fall with it. Conversion could bring about the total integration of the Jews into the prevailing social texture, and would put an end to the insulation, ambiguous status and, indeed, persecution of Jews sensible enough to follow this rational course. His parents’ theory was essentially the same as that which had moved Börne and Heine, as well as Heinrich Marx and Isaac d’Israeli – two fathers of famous sons – to embrace Christianity. The hypothesis was, in his view, baseless and degrading; and he, Ludwik Bernsztajn as he then was, came to understand this when he was still quite young, sixteen or seventeen. He felt himself in a false position, and realised that the converted Jews in his circle lived in an unreal world – had abandoned the traditional misery of their ancestors only to find themselves in a no-man’s-land between the two camps, welcome to neither. His father’s conventional, bourgeois outlook repelled him in any case. He decided to return to the Jewish community – at any rate in his own mind – partly because he believed that to attempt to cut oneself off from one’s own past was self-destructive and shameful, and in any case impracticable; partly because he wished to show his contempt for his family and their unworthy ideals. His father thought him ungrateful, foolish and perverse, and refused to support him. He went to England, which to him as to many Central and Eastern European Jews appeared the most civilised and humane society in the world, as well as one respectful of traditions, including his own. As part of his general revolt against his father’s way of life, which was in his mind associated with the mixture of corruption, hypocrisy and oppression by which the Austro-Hungarian Empire was governed, he was attracted to socialism. The false and humiliating lives lived by his parents and their society seemed to him largely due to systematic delusion about themselves and their position, and, in particular, the attitude towards them of the Poles, whether Austrianised or nationalist, among whom they lived. Marxism was the leading philosophy which attempted to explain away and to refute such liberal fantasies as so many disguises intended to conceal an irrational and unjust social order, and one based on ignorance or misinterpretation of the real (largely economic) facts.

When he arrived in London, he became a student at the London School of Economics, then dominated by the Webbs, Graham Wallas and their followers, who, if not Marxists, were socialists and militantly anti-Liberal. However, in due course he realised that he had simply left one set of delusive ideologies for another. The principles and generalisations of socialism were as silly and unrealistic as those it sought to supplant. The only reality was to be found in the individual and his basic desires – conscious and unconscious, particularly the latter, which were repressed and rationalised by a series of intellectual subterfuges, which Marxism had detected, but for which it had substituted illusions of its own. Individual psychology, not sociology, was the key. Human action – and social reality in general – could be explained only by fearless and dispassionate scientific examination of the roots of individual human behaviour – basic drives, permanent human cravings for food, shelter, power, sexual satisfaction, social recognition and so on. Nor was human history, and in particular political history, to be explained in any other way.

He was not disappointed in England. It took, as he had supposed, a humane, civilised and, above all, sober, undramatised, empirical view of life. Englishmen seemed to him to take account, more than most men, of the real ends of human life – pleasure, justice, power, freedom, glory, the sense of human solidarity which underlay both patriotism and adherence to tradition; above all they loathed abstract principles and general theories. Human motives could be illuminated by attention to unexamined, occult causes which Freud and other psychologists had begun to investigate. Nevertheless, even such overt considerations as were present to the mind of an average Englishman, far more than to that of, say, an average German or an average Pole, accounted for a great deal of human behaviour – a far larger sector of it than had been explained by the ‘ideologists’.

At some point in this discourse, delivered with a kind of controlled ferocity, Namier spoke – as he often later spoke – of the absurdity of those who attempted to account for human behaviour by invoking the influence of ideas. Ideas were mere interpretations by the mind of deep-seated drives and motives which it was too cowardly, or too conventionally brought up, to face. Historians of ideas were the least useful kind of historians.

‘Do you remember’, he asked me, ‘what Lueger, the anti-Semitic Mayor of Vienna, once said to the municipality of Vienna when a subsidy for the natural sciences was asked for? “Science? That is what one Jew cribs from another.”1 That is what I say about Ideengeschichte, history of ideas.’ Perhaps he saw a discontented expression on my face, for I well remember that he repeated all this again in still more formidable accents, and emphasised it over and over again in a slow, heavy, drawling voice, as he often did on later occasions.

The London School of Economics was not the England that he had admired from afar, and he felt this still more strongly when he met it face to face. It was a pathetic offshoot of the worst continental nonsense. He migrated to Balliol College, Oxford, and was there taught history by A. L. Smith and others. Oxford (he continued) had less truck with ideologies: here he could freely profess what he thought to be the deepest factor in modern history – the historically grounded sense of nationality. The notion that rational men, Jews or Gentiles, could live full lives either by dedication to a religion (organised falsification – rabbis were worse than priests, and lived on and by deception), or by abandoning their religion, or by emigrating to lands beyond the sea, or by any means other than those by which all other human communities had done so, that is, by organising themselves into political units and acquiring a soil of their own – all such notions were sheer nonsense. Self-understanding was everything, both in history and in individual life; and this could be achieved only by scrupulous empiricism, the continuous adaptation of one’s hypotheses to the twisted and obscure windings of individual and social lives. Hence his respect for Freud and other psychological theorists – including graphologists, in whom his faith was very strong – and his lack of respect for Marx, who had, indeed, correctly diagnosed the disease, but then had offered a charlatan’s nostrum. Still, that was better than Burke or Bentham, who peddled mere ideas rooted in nothing, and were rightly distrusted by sensible, practical politicians.

He returned to his autobiography: he had not been too well treated by England. He deserved a permanent post in Oxford, which he had not obtained. Scant recognition had been shown him by many established scholars, because they knew that he could ‘show them up’. Nevertheless, it was the only country to live in. It was less fanatical and closer to empirical reality than other nations, and there was in its political tradition a certain realism – some called it cynicism – which was worth all the vapid idealism and idiotic liberalism of the Continent. There were Englishmen who were taken in by continental ‘-isms’–here followed names of some eminent contemporaries – but they were relatively few and not too influential: the majority wisely went by habit and well-tried practical rules and kept clear of theory, thereby avoiding much nonsense in their ideas and brutality in their action. He could not talk to English Jews about Zionism. The Jews of England were victims of pathetic illusions – ostriches with their heads in some very inferior sands – foolish, ridiculous creatures not worth saving. But Englishmen understood its appeal and its justification. The only Jew he had ever met who in this respect could be compared to an Englishman was Weizmann – indeed, he was the only Zionist for whom he had complete respect. Upon this note he ended, and having, as must be supposed, diagnosed me sufficiently – although he took not the slightest notice of my occasional queries – he marched out of my room to tea with Kenneth Bell of Balliol, ‘whose family is very fond of me’, he added.

I felt flattered by his visit, as well as deeply impressed and slightly bewildered by his lecture. In the five or so years before the war I met him more than once. He spoke bitterly about the policy of appeasement. He felt that their sense of reality and their empiricism had evidently deserted the ruling classes in England: not to understand that Hitler meant everything he said – that Mein Kampf was to be taken literally, that Hitler had a plan for a war of conquest – was self-deception worthy of Germans or Jews. The Cecils were ‘all right’, they understood reality, they stood for what was most characteristic of England. So was Winston Churchill. The men who opposed Zionism were the same as those who were against Churchill and the policy of national resistance – Geoffrey Dawson, the editor of The Times, Chamberlain, Halifax, Toynbee, the officials of the Foreign Office, Archbishop Lang, the bulk of the Conservative Party, most trade unionists. The Cecils, Churchill, true aristocracy, pride, respect for human dignity, traditional virtues, resistance, Zionism, personal grandeur, no-nonsense realism, these were fused into one amalgam in his mind. Pro-Germans and pro-Arabs were one gang.

He spoke a good deal about Zionism to me, no doubt because he thought (rightly) that I was sympathetic. Gradually I became convinced that this was the deepest strain in him: and that he was fundamentally driven into it by sheer pride. He found the position of the Jews to be humiliating: he disliked those who put up with this or pretended that it did not exist. He wanted a free and dignified existence. He was intelligent enough to realise that to shed his Judaism, to assume protective colouring and disappear into the Gentile world, was not feasible, and a pathetic form of self-deception. If he was not to sink to the level of the majority of his brethren (whom on the whole he despised), if he had to remain one of them, as was historically inevitable, then there was only one way out – they must be pulled up to his own level. If this could not be achieved by slow, gradual, peaceful, kindly means, then it must be achieved by rapid and, if need be, somewhat drastic ones. He had not believed this to be wholly possible until he had met Weizmann, whom he admired to the point of hero-worship: here at least was a Jew whom he did not find it embarrassing to associate with, indeed, even to follow. But the other Zionist leaders appeared nonentities to him and he did not trouble to conceal this. He called them ‘the rabbis’ and said that they were no better than priests and clergymen – to him, then, terms of abuse. His Zionist colleagues valued his gifts but could scarcely be expected to enjoy his open and highly articulate contempt. Despite Weizmann’s favour, he was never made a permanent member of the World Zionist Executive – a fact that rankled with him for the rest of his life. Despite all his talk of realism and his historical method, he had the temperament of a political romantic. I am not sure that he did not indulge in daydreams in which he saw himself as a kind of Zionist d’Annunzio riding on a white horse to capture some Trans-Jordanian Fiume. He saw the Jewish national movement as a Risorgimento; if he was not to be its Garibaldi, he would serve as the adviser and champion of its Cavour – the sagacious, realistic, dignified, Europeanised, the almost English Weizmann.

Privately I used to think that in character, if not in ideas, Namier was not wholly unlike his bête noire, Karl Marx. Namier too was an intellectually formidable, at times aggressive, politically-minded intellectual – and his hatred of doctrine was held with a doctrinaire tenacity. Like Marx, he was vain, proud, contemptuous, intolerant, quick to give and take offence, master of his craft, confident of his own powers, not without a strain of pathos and self-pity. Like Marx, he hated all forms of weakness, sentimentality, idealistic liberalism; most of all he hated servility. Like Marx, he fascinated his interlocutors and oppressed them too. If you happened to be interested in the topic which he was discussing (Polish documents relating to the revolution of 1848, or English country houses), you were fortunate, for it was not likely that you would again hear the subject expounded with such learning, brilliance and originality. If, however, you were not interested, you could not escape. Hence those who met him were divided into some who looked on him as a man of genius and a dazzling talker and others who fled from him as an appalling bore. He was, in fact, both. He aroused admiration, enthusiasm and affection among his pupils and those who were sympathetic to his opinions; uneasy respect and embarrassed dislike among those who did not. If he came across latent anti-Semitism he stirred it into a flame; London clubmen (whom he often naively pursued) viewed him with distaste. Academics and civil servants – whom he bullied – loathed and denigrated him. Scholars looked on him as a man of prodigious powers and treated him with deep, if at times somewhat nervous, admiration.

I never experienced boredom in his company, not even when he was at his most ponderous. All the subjects that he discussed appeared to me, at any rate while he spoke about them, interesting and important; when in form he spoke marvellously. He spoke with sovereign, and often wholly unmitigated, contempt about other scholars, and indeed most other human beings. The only living persons wholly exempt from his disparagement were Winston Churchill, who could do no wrong; Weizmann, in whose presence Namier was simple, childlike, reverent, uncritical to the point of worship; and his great friend Blanche Dugdale, Balfour’s niece. He was said to be transformed in her presence, but I never saw them together. Nor do I know how he felt and what he said in the country houses which he visited for the purpose of examining their muniments and family papers. His pleasure in staying in them was part of the romantic Anglomania which remained with him to the end of his days. The English aristocracy was for him bathed in a heavenly light. His interest in history is certainly not alone sufficient to explain this radiant vision. Rather it is probably the other way about: his interest in the history of individual members of the English Parliament during a time when many of them were members of (or closely connected with) a powerful and gifted Whig aristocracy was due to his idealisation of this style of life. He has, at times, been accused of being a snob. There is something in this; but Namier’s snobbery was of the Proustian kind – peers, members of the aristocracy, rich, proud, self-possessed, independent, freedom-loving to the point of eccentricity – such Englishmen were for him works of art which he studied with devoted, indeed, fanatical attention and discrimination. He was not carried away by the fascination of this world, as Oscar Wilde, or even Henry James, appear to have been. He was content to remain an outsider. He gloried in his vision of the English national character, its strengths and its foibles, and remained a lifelong passionate addict to a single human species, to the analysis and, inevitably, celebration of which his life – for psychological reasons which Freud had certainly not helped him to understand – was devoted. He studied every detail in the life of the English governing class, as Marx studied the proletariat, not as an end in itself, as an object of fascinated observation, but as a social formation; in each case from an outside vantage-point, which neither bothered either to emphasise or to deny.

His origins obsessed him. His morbid hatred of obsequiousness, which may have had something to do with his memories of Poles and Jews in Galicia, often took ferocious forms. Meeting me in the corridor of a train, he said, apropros of nothing: ‘I have been visiting Lord Derby. He said to me: “Namier, you are a Jew. Why do you write our English history? Why do you not write Jewish history?” I replied, “Derby! There is no modern Jewish history, only a Jewish martyrology, and that is not amusing enough for me.” ’ He spoke of Jews as ‘my co-racials’, and clearly enjoyed the embarrassing effect which this word produced on Jew and Gentile alike. In All Souls one afternoon someone in his presence – he was in the common room at tea as a guest – defended the German claim to colonies, a topic then much in the air. Namier rose, glared round the room, fixed a basilisk-like eye on one of his fellow guests, whom he had, mistakenly as it turned out, assumed to be a German, and said loudly, ‘Wir Juden und die anderen Farbigen denken anders.’1 He savoured the effect of these startling words with great satisfaction.

He was an out-and-out nationalist, and did not disguise his far from fraternal feelings towards the Arabs in Palestine, about whom his position was more intransigent than that of the majority of his fellow Zionists. I well recollect a meeting to interview candidates for a post in English in the University of Jerusalem, at which Namier would fix some timid lecturer from, say, Nottingham, with his baleful, annihilating glare, and say: ‘Mr Levy, can you shoot?’ – the candidate would mutter something – ‘Because if you take this post, you will have to shoot. You will have to shoot our Arab cousins. Because if you do not shoot them, they will shoot you.’ Stunned silence. ‘Mr Levy, will you please answer my question: Can you shoot?’ Some of the candidates withdrew. No appointment was made.

As the 1930s wore on and the position of the West steadily deteriorated, Namier grew steadily gloomier and more ferocious. He would visit me in All Souls, and later in New College, and say that as war was now inevitable, he proposed to sell his life as dearly as possible, and paint imaginary pictures involving the extermination of a good many Nazis by all kinds of diabolical means. The position of Zionism – one of the victims of British foreign policy at this time – depressed him further. The villains in his eyes were not so much the Conservative leaders – some of those were members of the aristocracy and as such enjoyed a certain degree of exemption from blame – but the Arab-loving ‘pen-pushers of the Foreign Office’ and the ‘hypocritical idiots of the Colonial Office’. He would lie in wait for these – particularly the latter – in the Athenaeum. There he would drive some unsuspecting official into the corner of the smoking-room, where he would treat him to a terrifying homily which the victim would not soon forget, and which would probably increase his already violent antipathy to Zionism in general and Namier in particular.

Sir John Shuckburgh, then the Permanent Under-Secretary of the Colonial Office, was a not infrequent target for Namier when he was on the warpath. I was once present when Namier, in his soft but penetrating and remorseless voice, addressed Shuckburgh, who made every effort to escape; in vain. Namier followed him out of the room, on to the steps, into the street, and so on – down the Duke of York’s Steps, probably to the door of the Colonial Office itself. Politically he was as great a liability to his party as he was an asset to it intellectually. His final and most savagely treated victim was Malcolm MacDonald, the Colonial Secretary himself. In 1939, after the Chamberlain government’s White Paper on Palestine, which seemed to put an end to all Zionist hopes, Namier came to lunch with Reginald Coupland at All Souls. Coupland was the effective author of the Peel Report on Palestine, probably the most valuable document ever composed on that agonising subject. Coupland had spoken bitterly of the shameful betrayal of the Palestine Jews by the British Government, and said that he would write a letter to The Times pointing out the shortcomings of both Chamberlain and Malcolm MacDonald. Namier said that he had his own method of dealing with such cases. He had met Malcolm MacDonald somewhere in London. ‘I spoke to him. I began with a jest. I said that in the eighteenth century peers made their tutors Under-Secretaries, whereas in the twentieth Under-Secretaries made their tutors peers. He did not seem to understand. I did not bother to explain.1 Then I said something he would understand. I said to him, “Malcolm” – he is, you know, still Malcolm to me – I know him quite well – “I am writing a new book.” He said, “What is it, Lewis?” I replied, “I will tell you what it is. I have called it The Two MacDonalds: A Study in Treachery.” ’ I do not know whether Namier had actually said this; he supposed that he had and he was certainly capable of it. It was, again, not unlike Karl Marx at his most vindictive, and, like Marx’s insults, was intended to draw blood. Yet he was surprised by the fact that he was feared and disliked so widely.

In 1941 I was employed by the Ministry of Information in New York, and there I met a man who threw a good deal of light on Namier’s younger days. His name was Max Hammerling, and his father had been associated with Josef Bernsztajn, Namier’s father, in the management of his estate near Lemberg in Galicia, long before the First World War. The younger Hammerling was a warm sympathiser with the British cause, and got in touch with me to offer his help at a time when Britain was fighting Hitler alone. In the course of general conversation he asked me if I knew a man called Professor Namier, and was surprised to hear that I did. He said that he used to see him in earlier years, but that since then the connection had ended and he was anxious to hear what had happened to the son of his father’s associate. Hammerling Senior had, so his son told me, emigrated to America and acquired control of one or more of the foreign-language periodicals of New York in the years before the First World War. The young Namier first arrived in New York in 1913 with very little money – supplied by his father – to engage in research on the American War of Independence. Josef Bernsztajn had made an arrangement with his old associate under which Hammerling engaged Namier to write leading articles to be syndicated and translated for a section of his publications. Namier wrote these articles at night, and worked in the New York Public Library in the daytime, and in this way kept body and soul together. According to Max Hammerling, Namier viewed the continued existence of the Dual Monarchy with extreme disfavour, and was a vigorous champion of the Entente Cordiale. Hammerling Senior had many Roman Catholic readers and had no great wish to alienate the Roman Church in the United States, which was on the whole pro-Austrian and isolationist. When Namier’s articles became too violently interventionist, he was told to moderate them: he ignored hints and requests; matters came to a head, and his employment came to an end in the spring of 1914. It was then that Namier, without any obvious means of subsistence, returned to England and was given a grant by Balliol College which enabled him to continue his research. Namier told me that the news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was brought to the editor of The Times, Geoffrey Dawson, in All Souls after dinner. Namier, who happened to be there too, announced to Dawson and his friends that war was now imminent. Dawson indicated that he did not believe this (he laboured under similar delusions in 1938–9) and turned to other topics.

When war was declared Namier volunteered for the British Army. He was evidently not a perfect soldier. Some intelligent person took him out of the army, and put him into the Foreign Office as adviser on Polish affairs attached to the Historical Adviser to the Foreign Office, Sir John Headlam-Morley. ‘I remember’, said Namier to me, ‘the day in 1918 when the Emperor Karl sued for peace. I said to Headlam-Morley: “Wait.” Headlam-Morley said to Balfour: “Wait.” Balfour said to Lloyd George: “Wait.” Lloyd George said to Wilson: “Wait.” And while they waited, the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated.1 I may say that I pulled it to pieces with my own hands.’

Apart from feeling convinced that the Polish National Democratic Party was plotting his assassination, Namier enjoyed his work in the Foreign Office. The Foreign Office showed no desire to retain Namier on its staff after the war, nor did the Treasury, with which he also was temporarily connected. Nor did Balliol College, Oxford, which made him a temporary lecturer for a while – his most devoted Oxford pupils date from this period. Thereupon he left England for Vienna, and there made a few thousand pounds. In the early 1920s he came back to London with his exiguous capital. Here his extraordinary character showed itself at its fullest. He did not do what others might have been tempted to do: he did not try to spend as little as possible while looking for a means of subsistence; he knew that he had it in him to write an original and important book and decided to do so. He spoke of this to friends and allies (some of them connected with the Round Table group of Liberal Imperialists with whose ideas Namier had been in sympathy during the war). He told them that he needed money to write a book; he held out no promise of repayment: the money was to be regarded as an investment in learning and in that alone. Philip Kerr, who was among those approached, told me (in 1940 in Washington, where he was by then Lord Lothian and British ambassador) that he did not find Namier congenial company, but was overawed by his leonine personality and felt him to be a man of unusual intellectual power. He and his friends obtained a grant for him; he was also supported by at least one private person.

Namier felt no false shame in accepting such patronage: this was usual enough in that best of all periods, the later years of the eighteenth century. He felt that he had as good a claim as Burke, or any other talented writer of the past, whom the rich and the powerful should be proud to support; and he bound his spell upon his ‘patrons’, who, as he had always known, had no cause to regret their generosity. The books that he wrote did what he wished them to do: they transformed the standards of historical scholarship (and to some degree the style of historical writing) in England for at least a quarter of a century.

Having discharged this intellectual obligation, Namier threw himself, in the later 1920s, with passion and ferocity into political work in the Zionist Organization. This gave full play to his formidable gifts: his polemical skill, his sense of history, his pride, his nationalism, his passion for exposing weakness, cowardice, lies and unworthy motives. He derived deep satisfaction from these labours. In the course of them he managed to irritate and humiliate his less talented collaborators, to impress some members of the British intelligentsia, astonish and anger others, and permanently upset and infuriate a number of influential officials in the Foreign and Colonial Offices. After the Second World War, when it became plain that his unwavering and withering contempt for most of his Zionist colleagues had made it certain that if an independent Jewish establishment ever emerged he would not be amongst its guides, he turned his back upon Zionist politics, without changing his moral or political convictions. He returned to the study of history.

He hoped and expected, not without reason, that he might yet be appointed to a post by his alma mater. This was not to be. Whenever a chair in history (or international relations, on which, too, he had made himself a leading expert) fell vacant, his name inevitably came up and was duly dismissed. Those responsible for such appointments in Oxford often said that it was a crying shame that some other group of electors had failed to appoint Namier to one or other of the three or four chairs for which his distinction fitted him pre-eminently. But when their own turn came, such electors or advisers acted precisely like their predecessors. He was invariably passed over. Various reasons were adduced: that his field of specialisation was too narrow; that he was politically intemperate, as his Zionism or his low opinion of pre-war British foreign policy plainly showed; that he would be too arrogant to his colleagues or too exacting to his students; that he would be a terrible bore, intolerable at mealtimes to the fellows of this or that college. The quality of his genius was not seriously disputed: but this was not regarded as a sufficiently weighty factor. He had made some implacable enemies.

Yet, despite his acuteness, he was an unworldly man, and in personal matters clumsy, innocent and childlike. He was easily deceived: he took flattery for true coin. He often had no notion of who was covertly working against him: he was totally incapable of manoeuvre or intrigue. He achieved everything by the sheer weight of his huge intellectual armour. He misjudged motives and often could not tell friends from ill-wishers. He fell into traps and remained to his dying day unaware of this. He was an Othello who retained confidence in more than one minor academic Iago. His failure to obtain an Oxford Chair ate into his soul, as it has into those of others similarly treated. ‘I will tell you how they make professors in Oxford,’ he said bitterly to me during the period when he was delivering the Waynflete Lectures at Magdalen College shortly after the end of the Second World War. ‘In the eighteenth century there was a club called the Koran Club. The qualification for membership was to have travelled in the East. Then it was found that there were various persons whom it was thought desirable to make members of the club and who had not travelled in the East. So the rules were changed from “travelling in the East” to “expressing a wish to travel in the East”. That is how they make professors in Oxford. Do not’, he added, ‘let this story go too far.’

He continued to teach at Manchester, but finally moved to London and was entrusted with the formidable enterprise of the History of Parliament, to be done in his own fashion – by means of detailed, microscopically examined lives of all who ever were members of it. Honours were showered upon him in England and abroad, but nothing made up for the Oxford disappointment. Balliol made him an honorary fellow. Two honorary doctorates were conferred upon him by the University. He delivered the Romanes Lecture. But although this pleased him, as did his knighthood, the old scar remained and troubled him.

It was at this period that he married for the second time (his first marriage had not lasted long – his wife is said to have been a Muslim and died during the Second World War). He was converted to the Anglican faith, and his marriage to Julia de Beausobre finally ended the period of acute loneliness and bitter personal unhappiness, mitigated by rare moments of pride and joy, which had begun for him after the First World War. Friedrich Waismann, an eminent Austrian philosopher whom he had met during his years in Vienna, told me that he had never in his life met an intellectually more gifted, penetrating and fascinating man, or one more deeply plunged in the most hopeless misery and solitude.

His conversion to Christianity cost him the friendship of Weizmann, who did not wish to examine the reasons for this step, but reacted instinctively, as his fathers would have done before him, to what he regarded as an act of apostasy for which no decent motive could exist. This, of course, hurt Namier deeply, but his marriage had created a new life for him and he bore such things more easily. He visited the State of Israel after Weizmann’s death, was profoundly moved, but remained implacably opposed to the rabbis and complained of clerical tyranny. When I made light of this to him he turned upon me sternly and said ‘You do not know rabbis and priests as I do – they can ruin any country. Clergymen are harmless. Nobody ever speaks of being in the hands of the clergymen as they do of the Jesuits and, I fear, now should do of the rabbis.’ During this period I would receive occasional visits from him in Oxford. He had grown mellower with age; he was happier because his domestic life was serene, and because adequate recognition had been given him at last. He took criticism as painfully as ever: when his friend and disciple Alan Taylor wrote an insufficiently respectful review of a collection of his essays in the Manchester Guardian, he, like Marx, took this as a symptom of failing powers on the part of the critic.

He invested a great deal in his few personal relationships, and breaches were particularly painful to him. His relations with Taylor suffered further deterioration, in large part as a result of the role which Taylor believed him to have played in the choice of the successor to V. H. Galbraith as Regius Professor of History in Oxford. Taylor was not appointed; he blamed Namier for failing to support him sufficiently when he could have done so, and broke off relations. Namier was genuinely fond of him – fonder of him than of most men. He told me that some of his happiest hours had been spent at Taylor’s house; that one must be careful – more careful than he had been – in one’s human relations; but that Taylor, whose gifts were so extraordinary, had disappointed him by what he considered his addiction to popular journalism. ‘And if I have hurt your feelings,’ he said to me, ‘I apologise also. I am not always too careful’: this was a touching and handsome reference to the fact that I had sent him the printed version of a lecture on an abstract subject, which he had acknowledged with the words ‘how intelligent you must be to understand all you write’.1

This was a characteristic gibe aimed at the philosophy of history – a subject which he believed to be bogus, and which had been the subject of my lecture. I was delighted by his letter, which could not have been regarded as offensive by any normal person, still less by anyone who knew Namier and took pleasure in his prejudices and absurdities. E. H. Carr, who was a common friend, came to visit me on the day when I received it, and I read him Namier’s letter with great relish. Shortly afterwards Namier’s comment appeared in a gossip column of the Daily Express. Namier was horrified, and wrote to me immediately to explain that he had not, of course, meant to insult either me or the subject of my lecture. My reassurances did not convince him: he suspected Carr – quite baselessly, since Carr flatly denied this – of communicating the gibe to the Daily Express; serious journalism was, of course, another matter. How could such serious, learned, gifted men, Taylor, Carr, fellows of the British Academy, who had it in them to give so much to historical study, compromise the dignity of their calling – and of academic life generally – by associating with the enemies of learning, however entertaining and informative? And in so public a fashion? At least Butterfield, than whom no one was more mistaken, did not dabble in this. Namier’s suspicions were often (as in this case) without foundations; but he clung to them. My defence fell on deaf ears: an idealised image, which he had carried with him for the greater part of his life – the image of the scholar, and perhaps also of the Englishman – had in some way been damaged, and this was almost more painful than a personal attack.

He spoke often of the dignity of learning: of the need to keep scholarship pure, to protect it from its three greatest enemies, amateurism, journalistic prostitution, and obsession with doctrine. ‘An amateur’, he declared in one of his typical apophthegms, ‘is a man who thinks more about himself than about his subject’, and he mentioned a younger colleague whom he suspected of a wish to glitter. He passionately believed in professionalism in every field: he denounced fine writing, and, still more, a desire to startle or shock the reader, whether he was a member of the general public or of the world of scholars. He spoke with indignation about those who had accused him of wishing to reassess the character and historical influence of George III out of a desire to dish the Whigs and attack their values and their heroes. He would solemnly and with deep sincerity assure me that his sole purpose was to reconstruct the facts and explain them by the use of well-tested, severely empirical methods; that his only reason for distrusting party labels and professions of political ideals in the eighteenth century was his conviction – based on incontrovertible documentary and other factual evidence – that such labels and professions disguised the truth, often from the agents themselves. His own psychological tenets, on which these exposures were in part based, seemed to him confirmed over and over again by the historical evidence – the actual transactions of the politicians and their agents and their kinsfolk – which were susceptible of one and only one true explanation. Whether or not he was mistaken in this, he believed profoundly that he was guided not by theories but by the facts and by them alone. As for the question of what was a fact, what constituted evidence, this was a philosophical issue – something from which he shied with all the force of his whole abstraction-hating, anti-philosophical nature.

Journalism – the desire to épater, to entertain, to be brilliant – was, in a man of learning, mere irresponsibility. ‘Irresponsible’ was one of the most opprobrious terms in his vocabulary. His belief in the moral duties of historians and scholars generally was Kantian in its severity and genuineness. As for doctrinaire obsessions, that again appeared to him as a form of culpable self-indulgence – wanton escape from the duty of following minutely, wherever they led, the often complex, convoluted empirical paths constituted by the ‘facts’, into some symmetrical pattern invented by the historian to indulge his own metaphysical or moral predilection; alternatively it was a quasi-pathological intellectual obsession which rendered the historian literally incapable of seeing ‘wie es eigentlich gewesen’.1 Hence Namier’s distaste for, and ironies at the expense of, philosophical historians; and the emphasis on material factors and distrust of ideal ones. This was odd in a man who was himself governed by so many ideals and indeed prejudices: nationalism and national character, love of traditional ‘roots’, la terre et les morts,2 disbelief in the efficacy of intellectuals and theorisers, faith in individual psychology, even in graphology, as a key to character and action. But it was so.

It is not perhaps too extravagant to classify his essentially deflationary tendency – the desire to reduce both the general propositions and the impressionism of historians to hard pellet-like ‘facts’, to bring everything down to brass tacks – to regard this as part of the dominant intellectual trend of his age and milieu. It was in Vienna, after all, that Ernst Mach enunciated the principles of ‘economy of thought’ and tried to reduce physical phenomena to clusters of identifiable, almost isolable, sensations; that Freud looked for ‘material’, empirically testable causes of psychical phenomena; that the Vienna Circle of philosophers generated the verification principle as a weapon against vagueness, transcendentalism, theology, metaphysics; that the Bauhaus with its clear, rational lines had its origin in the ideas of Adolf Loos and his disciples. Vienna was the centre of the new anti-metaphysical and anti-impressionist positivism. Whether he knew this or not – and nobody could protest more vehemently against such ideological categorisation – this was the world from which Namier came. Its most original thinkers had reacted violently against German metaphysics and had found British empiricism sympathetic. In philosophy they achieved a celebrated and fruitful symbiosis with British thought. Namier was one of the boldest and most revolutionary pioneers of the application of this very method to history. The method – especially in the work of his followers – has been criticised as having gone too far – ‘taken the mind out of history’.1 This kind of criticism has been levelled no less at the corresponding schools of philosophy, art, architecture, psychology. Whether the charge is just or not, even its sharpest critics can scarcely deny the value and importance of the early impact of the new method. It opened windows, let in air, revealed new horizons, made men see what they had not seen before. In this great constructive-destructive movement Namier was a major figure.

Namier’s most striking personal characteristics were an unremittingly active intellectual power, independence, lack of fear, and an unswerving devotion to his chosen method. This method had yielded him rich fruit, and he would not modify it merely because it seemed to eclectics or philistines to be extreme or fanatical. Like Marx, like Darwin, like Freud, he was severely anti-eclectic. Nor did he believe in practising moderation or introducing qualifications simply in order to avoid charges of extremism, to please men of good sense. Indeed, anxiety to please in any fashion, still less appeasement of critics, was remote from his temperament. He believed that objective truth could be discovered, and that he had found a method of doing so in history; that this method consisted in a sort of pointillism, the ‘microscopic method’,1 the splitting up of social facts into details of individual lives – atomic entities, the careers of which could be precisely verified; and that these atoms could then be integrated into greater wholes. This was the nearest to scientific method that was attainable in history, and he would adhere to it at whatever cost, in spite of all criticism, until and unless he became convinced by internal criteria of its inadequacy, because it had failed to produce results verified by research. This psychological Cartesianism was his weapon against impressionism and dilettantism of every kind. Kant had said that nature would yield up her secrets only under torture, only if specific questions were put to her. Namier believed this of history. The questions had to be formulated in such a way as to be answerable.

He was a child of a positivistic, deflationary, anti-romantic age, and his deep natural romanticism came out in other – political – directions. Dedicated historian that he was, he deliberately confined himself to his atomic data. He did indeed split up his material and reduce it to tiny fragments, which he then reintegrated with a marvellous power of imaginative generalisation as great as that of any other historian of his time. He was not a narrative historian, and underestimated the importance and the influence of ideas. He admired individual greatness, and despised equality, mediocrity, stupidity. He worshipped political and personal liberty. His attitude to economic facts was at best ambivalent: and he was a very half-hearted determinist in his writing of history, whatever he may have said about it in his theoretical essays. Materialism, excessive determinism, were criticisms levelled against him, but they fit better those historians who, using the method without the genius, tend towards pedantry and timidity, where he was boldly constructive, intuitive and untrammelled. He thought in large terms. The care with which he examined and described the individual trees did not obscure his vision of the wood for the sake of which the huge accumulation and the minute analyses had been undertaken; the end, at any rate in the works of his best period, is never lost to view; the reader is not cluttered with detail, never feels that he is in the grasp of an avid fact-gatherer who cannot let anything go, a fanatical antiquary who can no longer distinguish between the trivial and the important. Perhaps, towards the end of his life, trees and even shrubs did begin to obscure his vision of the wood. But when he was at his best he might well have said, echoing Marx, for whom he had so little respect and by whose method he was in practice much influenced: ‘Surtout, je ne suis pas namieriste.’1

1 ‘Zionism’, New Statesman, 5 November 1927, 103–4; reprinted in Skyscrapers and Other Essays (London, 1931). Cf. ‘The Jews’, The Nineteenth Century and After 130 (July–December 1941), 270–7; reprinted in Conflicts (London, 1942).

1 ‘I have always had a certain grudge against Grant Robertson, who, as examiner, had preferred Cruttwell to myself,’ Namier said to me in the late 1930s, ‘but when I think of what he has done for the German-Jewish refugees – I forgive him.’

1 He quoted this with much relish in German: ‘was ein Jud’ vom andern Juden abschreibt’. But for once he appears to have been inaccurate. The real author, I have since learnt, appears to have been Hermann Bielohlawek, a member of Lueger’s Christian-Social party in the Austrian parliament, of Czech origin, who apparently once said ‘Literatur ist was ein Jud’ vom andern abschreibt.’

1 ‘We Jews and the other coloured peoples think otherwise.’

1 Only Namier would have supposed that the average educated Englishman (or Scotsman) would realise that he was referring to the fact that the philosopher Locke had been made an Under-Secretary by his ex-pupil, Lord Shaftesbury, and that Godfrey Elton, who had been Malcolm MacDonald’s tutor at Queen’s College, Oxford, had recently been elevated to the peerage.

1 Namier pronounced this word very slowly, syllable by syllable, which heightened the dramatic climax of his narrative.

1 Letter of 10 February 1955, thanking IB for a copy of Historical Inevitability.

1 [‘As it really was’.]

2 [A recurrent nationalist leitmotiv used by Barrès (and by later writers following his lead). A prominent occurrence is in the title of a lecture written for (but not delivered to) La Patrie Française: Maurice Barrès, La Terre et les morts (Sur quelles réalités fonder la conscience française) [Land and the Dead: The Realities on Which to Base French Consciousness] ([Ligue de] La Patrie Française, Troisième Conférence) (Paris, [1899]).]

1 See A. J. P. Taylor, ‘Accident Prone, or What Happened Next’, Journal of Modern History 1 (1977), 1–18 at 9.

1 Ved Mehta, Fly and the Fly-Bottle: Encounters with British Intellectuals (London, 1963), 182.

1 [‘Above all, I am not a Namierist.’ Marx’s collaborator Friedrich Engels recounts in two letters two versions of a remark made by Marx in French to his son-in-law Paul Lafargue: 2–3 November 1882 to Eduard Bernstein, ‘What is certain is that I am not a Marxist’; 5 August 1890 to Conrad Schmidt, ‘All I know is that I am not a Marxist.’]