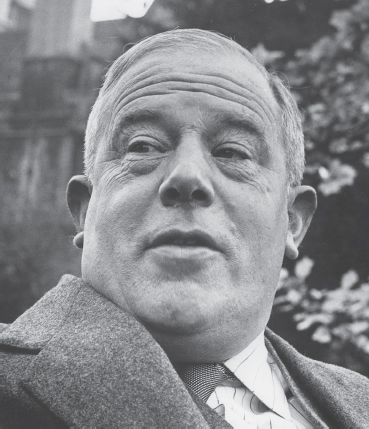

MAURICE BOWRA, SCHOLAR, critic and administrator, the greatest English wit of his day, was, above all, a generous and warm-hearted man, whose powerful personality transformed the lives and outlook of many who came under his wide and life-giving influence. According to a contemporary at Cheltenham, he was fully formed by the time he left school for the army in 1916. In firmness of character he resembled his father, of whom he always spoke with deep affection and respect; but unlike him he was rebellious by temperament and, when he came up to New College in 1919, he became the natural leader of a group of intellectually gifted contemporaries passionately opposed to the conventional wisdom and moral code of those who formed pre-war Oxford opinion. He remained critical of all establishments for ever after.

Bowra loved life in all its manifestations. He loved the sun, the sea, warmth, light, and hated cold and darkness, physical, intellectual, moral, political. All his life he liked freedom, individuality, independence, and detested everything that seemed to him to cramp and constrict the forces of human vitality, no matter what spiritual achievements such self-mortifying asceticism might have to its credit. His passion for the Mediterranean and its cultures was of a piece with this: he loved pleasure, exuberance, the richest fruits of nature and civilisation, the fullest expression of human feeling, uninhibited by a Manichean sense of guilt. Consequently he had little sympathy for those who recoiled from the forces of life – cautious, calculating conformists, or those who seemed to him prigs or prudes who winced at high vitality or passion, and were too easily shocked by vehemence and candour. Hence his impatience with philistine majorities in the academic and official and commercial worlds, and equally with cultural coteries which appeared to him thin, or old-maidish, or disapproving. He believed in fullness of life.

Romantic exaggeration, such as he found in the early 1930s in the circle formed round the German poet Stefan George, appealed to him far more than British reticence. With a temperament that resembled men of an older generation – Winston Churchill or Thomas Beecham – he admired genius, splendour, eloquence, the grand style, and had no fear of orchestral colour; the chamber music of Bloomsbury was not for him. He found his ideal vision in the classical world: the Greeks were his first and last love. His first and best book was a study of Homer; this, too, was the topic of his last book, had he lived to complete it.1 Despite the vast sweep of his literary interests – from the epic songs of Central Africa to the youngest poets of his own day – it is Pindar, Sophocles, the Greek lyric poets who engaged his deepest feelings. Murray and Wilamowitz meant more to him than scholars and critics of other literatures.

Endowed with a sharp, quick brain, a masterful personality, an impulsive heart, great gaiety, a brilliant, ironical wit, contempt for all that was solemn, pompous and craven, he soon came to dominate his circle of friends and acquaintances. Yet he suffered all his life from a certain lack of confidence: he needed constant reassurance. His disciplined habits, his belief in, and capacity for, hard, methodical work, in which much of his day was spent, his respect for professionalism and distaste for dilettantism, all these seemed, in some measure, defensive weapons against ultimate self-distrust. So, indeed, was his Byronic irony about the very romantic values that were closest to his heart. The treatment of him at New College by that stern trainer of philosophers, H. W. B. Joseph, undermined his faith in his own intellectual capacity, which his other tutor in philosophy, Alick Smith, who did much for him, and became a lifelong friend, could not wholly restore.

Bowra saw life as a series of hurdles, a succession of fences to take: there were books, articles, reviews to write; pupils to teach, lectures to deliver; committees, even social occasions, were so many challenges to be met, no less so than the real ordeals – attacks by hostile critics, or vicissitudes of personal relationships, or the hazards of health. In the company of a few familiar friends, on whose loyalty he could rely, he relaxed and often was easy, gentle and at peace. But the outer world was full of obstacles to be taken at a run; at times he stumbled, and was wounded: he took such reverses with a stiff upper lip; and then, at once, energetically moved forward to the next task. Hence, it may be, his need and craving for recognition, and the corresponding pleasure he took in the many honours he received. The flat, pedestrian, lucid, well-ordered but, at times, conventional style and content of his published writings may also be due to this peculiar lack of faith in his own true and splendid gifts. His private letters, his private verse, and above all his conversation, were a very different matter. Those who know him solely through his published works can have no inkling of his genius.

As a talker he could be incomparable. His wit was verbal and cumulative: the words came in short, sharp bursts of precisely aimed, concentrated fire, as image, pun, metaphor, parody seemed spontaneously to generate one another in a succession of marvellously imaginative patterns, sometimes rising to high, wildly comical fantasy. His unique accent, idiom, voice, the structure of his sentences became a magnetic model which affected the style of speech, writing, and perhaps feeling, of many who came under its spell. It had a marked effect on some among the best-known Oxford-bred writers of our time. But his influence went deeper than this: he dared to say things which others thought or felt, but were prevented from uttering by rules or convention or personal inhibitions. Maurice Bowra broke through some of these social and psychological barriers, and the young men who gathered round him in the 1920s and 1930s, stimulated by his unrestrained talk, let themselves go in their turn.

Bowra was a major liberating force: the free range of his talk about art, personalities, poetry, civilisations, private life, his disregard of accepted rules, his passionate praise of friends and unbridled denunciation of enemies produced an intoxicating effect. Some eyebrows were raised, especially among the older dons, at the dangers of such licence. They were wholly mistaken. The result, no matter how frivolous the content, was deeply and permanently emancipating. It blew up much that was false, pretentious, absurd; the effect was cathartic; it made for truth, human feeling, as well as great mental exhilaration. The host (and he was always host, whether in his own rooms or those of others) was a positive personality; his character was cast in a major key: there was nothing corrosive or decadent or embittered in all this talk, no matter how irreverent or indiscreet or extravagant or unconcerned with justice it was.

As a scholar, and especially as a critic, Bowra had his limitations. His most valuable quality was his deep and unquenchable love of literature, in particular of poetry, of all periods and peoples. His travels in Russia before the Revolution, when as a schoolboy he crossed that country on his way to his family’s home in China, gave him a lifelong interest in Russian poetry. He learnt Russian as a literary language, and virtually alone in England happily (and successfully) parsed the obscurest lines of modern Russian poets as he did the verse of Pindar or Alcaeus. He read French, German, Italian and Spanish, and had a sense of world literature as a single firmament, studded with works of genius, the quality of which he laboured to communicate. He was one of the very few Englishmen equally well known to, and valued by, Pasternak and Quasimodo, Neruda and Seferis, and took proper pride in this. It was all, for him, part of the war against embattled philistinism, pedantic learning, parochialism. Yet he was, with all this, a stout-hearted patriot, as anyone could testify who heard him in Boston, for example, when England was even mildly criticised. Consequently, the fact that no post in the public service was offered him in the Second World War distressed him. He was disappointed, too, when he was not appointed to the Chair of Greek at Oxford (he was offered chairs by Harvard and other distinguished universities). But later he came to look on this as a blessing in disguise; for his election as Warden of Wadham eventually made up and more than made up for it all.

Loyalty was the quality which, perhaps, he most admired, and one with which he was himself richly endowed. His devotion to Oxford, and in particular to Wadham, sustained him during the second, less worldly, portion of his life. He did a very great deal for his College, and it did much for him. He was intensely and, indeed, fiercely proud of Wadham, and of all its inhabitants, senior and junior; he seemed to be on excellent terms with every undergraduate in its rapidly expanding population; he guided them and helped them, and performed many acts of kindness by stealth. In his last decades he was happiest in his common room, or when entertaining colleagues or undergraduates; happiest of all when surrounded by friends, old or young, on whose love and loyalty he could depend.

After Wadham his greatest love was for the University: he served it faithfully as Proctor, member of the Hebdomadal Council, and of many other committees, as Delegate of the Press, finally as Vice-Chancellor. Suspected in his younger days of being a cynical epicure (no less cynical man ever breathed), he came to be respected as one of the most devoted, effective and progressive of academic statesmen. He had a very strong institutional sense: his presidency of the British Academy was a very happy period of his life. Under his enlightened leadership the Academy prospered. But it was Oxford that claimed his deeper allegiance: the progress of the University filled him with intense and lasting pride. Oxford and Wadham were his home and his life; his soul was bound up with both. Of the many honours which he received, the honorary doctorate of his own University gave him the deepest satisfaction: the opinion of his colleagues was all in all to him. When the time for retirement came, he was deeply grateful to his college for making it possible for him to continue to live within its walls. His successor was an old personal friend: he felt sure of affection and attention.

Increasing ill health and deafness cut him off from many pleasures, chief among them committees and the day-to-day business of administration, which he missed as much as the now less accessible pleasures of social life. Yet his courage, his gaiety, his determination to make the most of what opportunities remained did not desert him. His sense of the ridiculous was still acute; his sense of fantasy remained a mainstay. New faces continued to feed his appetite for life. Most of all he now enjoyed his contact with the young, whose minds and hearts he understood, and whose desire to resist authority and the imposition of frustrating rules he instinctively shared and boldly supported to the end. They felt this and responded to him, and this made him happy.

He was not politically-minded. But by temperament he was a radical and a nonconformist. He genuinely loathed reactionary views and had neither liking nor respect for the solid pillars of any establishment. He sympathised with the unions in the General Strike of 1926; he spoke with passion at an Oxford meeting against the suppression of socialists in Vienna by Dollfuss in 1934; he detested oppression and repression, whether by the right or by the left, and in particular all dictators. His friendship with Hugh Gaitskell was a source of pleasure to him. If political sentiments which seemed to him retrograde or disreputable were uttered in his presence, he was not silent and showed his anger. He did not enjoy the altercations to which this tended to lead, but would have felt it shameful to run away from them; he possessed a high degree of civil courage. He supported all libertarian causes, particularly minorities seeking freedom or independence, the more unpopular the better. Amongst his chief pleasures in the late 1950s and 1960s were the Hellenic cruises in which he took part every year. But when the military regime in Greece took over, he gave them up.

His attitude to religion was more complicated and obscure: he had a feeling for religious experience; he had no sympathy for positivist or materialist creeds. But to try to summarise his spiritual outlook in a phrase would be absurd as well as arrogant. As Warden he is said scarcely ever to have missed Chapel.

The last evening of his life was spent at a convivial party with colleagues and undergraduates. This may have hastened the heart attack of which he died; if so, it was as he would have wished it to be: he wanted to end swiftly and tidily, as he had lived, before life had become a painful burden.

He was, in his prime, the most discussed Oxford personality since Jowett, and in every way no less remarkable and no less memorable.

1 [Nine out of ten chapters were found after his death, and the book (Homer) was published in London in 1972. His first book was Tradition and Design in the Iliad (Oxford, 1930).]