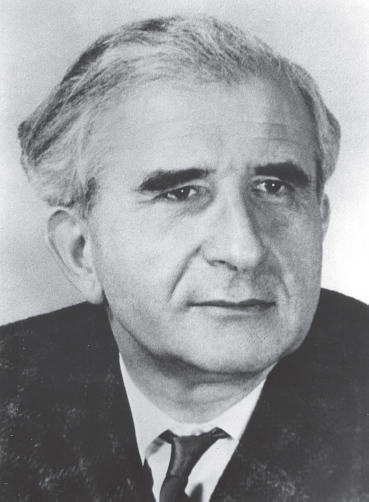

JOHN PLAMENATZ WAS BORN IN 1912 in Cetinje, the capital of Montenegro. Both his parents belonged to the ruling families of that old, pre-industrial, half-pastoral society, and although his life was lived almost entirely in England, his imagination and his feelings were dominated by his deep attachment to his native land. In 1917, when he was five years old, he was taken by his father to France, and soon after that to England, where he was placed in Clayesmore School, near Winchester, whose headmaster his father knew. There he stayed for the next eleven years, while the school moved from place to place, until he came to Oriel College, Oxford, in 1930. From time to time his parents summoned him to visit them during his school holidays, to Marseilles or Vienna, but for long stretches of time he lived apart from his family, and became used to solitude. He spent four years at Oriel; illness prevented him from completing his papers in PPE1 and he obtained an aegrotat; and, a year later, a First in History. In 1936 he was elected to All Souls, the first fellow to be elected by thesis since Dearle, early in the century.

He spent the rest of his life in Oxford, and his work and his influence are part of the intellectual history of Britain and of that university. But there is a sense in which he remained in exile all his life. He was never wholly assimilated either to England or to Oxford: when he said ‘we’ – ‘This is the way we think’, or ‘This is how it is with us’ – he usually meant Montenegrins. He once said to me that he had made personal friends among individual English people; that he could feel at home with two or three at a time; but that when more than two or three were gathered in a room, he would become aware of a relationship between them, from which he felt excluded. He explained this by saying that he was rooted in a remote culture, that the sudden break in early childhood – the emigration to an alien environment – had forced him to turn, to some degree, in upon himself. Those who knew him can testify to the fact that, like Joseph Conrad (whom in some ways he resembled), all his life he displayed the pride and independence of a noble exile.

‘Displayed’ is the wrong term: John Plamenatz displayed nothing; he was reserved and reticent; he did not seek to put himself forward or impose his personality in any way on any occasion that I know of. He spoke his mind with candour and precision, and with the great natural courtesy that was an essential attribute of his character; yet, at times, one could not be sure about what was going on inside his mind – there was something remote and unapproachable about him; but when one came to know him well, this melted – he was a warm and affectionate friend. But neither friendship nor its absence ever blinded him to human character and motives; he was acutely perceptive – that somewhat myopic eye saw a very great deal. He was occasionally deceived by persons and situations, but not often. Above all, he was not anxious to judge. At times he commented upon individuals, or on the social scene, with amused irony, but in general he showed the kind of tolerance that only deeply civilised or saintly people can achieve. But, of course, there were qualities he found unbearable: he disliked shoddiness, triviality, ostentation, stridency, vulgarity and opportunism of every sort; he detested rudeness; he was upset by lack of manners, the sources of which he found it difficult to comprehend. He prized privacy and personal relations above all. He was gentle, dignified and wholly uncompetitive; he was interested in the character of others, and sensitive to their feelings, particularly to the feelings of those who, like himself, wished to walk by themselves and found it difficult to fit in with established social patterns. He spoke to such people more easily, and defended them against the criticisms of those who thought them farouche or unattractive. He understood loneliness, unhappiness, vulnerability better, I think, than anyone I have ever known. All Souls, in the years before the war, was full of animated talk by politicians and academics about the burning social and political questions of the day: John Plamenatz avoided such gatherings; his interest in the problems was just as great as that of a good many others, and his understanding of them sometimes more sensitive, but he disliked the noise, the jokes, the rivalry, the repartee, the high spirits – genuine or false – of such exchanges. He seldom attended gaudies.

College meetings were another matter. These he took very seriously and, though he spoke little, when he did intervene the effect was sometimes decisive: he spoke quietly, with obvious conviction, without the slightest hint of rhetoric. He did not speak unless he had something of central relevance to say or ask: his motives were so completely free from any touch of calculation, his sincerity was so evident, that his apparently simple statements or questions, penetrating as they often did to the heart of some debated issue, tended to have a devastating effect. The word ‘integrity’ might have been invented for him. His words were listened to with deep respect, and on the rare occasions when he felt genuinely moved, he almost always carried the day. The independence, the scrupulous regard for the truth, the shining impartiality of his judgement were a unique moral asset to every society of which he was a member. It was so at All Souls, and, I am told, it was so at Nuffield also.

It was a singular irony, therefore, that the D.Phil. thesis that he submitted should have been failed by the examiners, on the ground, it was rumoured, of ‘lack of judgement’. This was the very thesis on the strength of which he was, a little later, elected to All Souls. When it was published, its quality was plain for all to see. He came to be critical of it himself in later years. Nevertheless, it was, in the opinion of competent critics, probably the best work on political theory produced by anyone in Oxford since the First World War.1 It was the first in a long line of books that did more than any other single factor to transform the level of the entire discussion of political theory in Oxford. His work served to raise its standards to that of serious philosophical argument. The judgement passed upon it was perhaps the greatest miscarriage of academic justice known to my generation. He was, of course, hurt by it at the time, but in the end ignored it – it left no obvious wound.

His intellectual weapons were derived from that sober, pre-positivist, pre-linguistic, realist tradition in moral philosophy to which his tutor, W. G. Maclagan, belonged, and which was dominant in Oxford in the early 1930s. The purpose of its method was to state the arguments – one’s own or those of others, particularly the great thinkers of the past – in the clearest possible fashion – to avoid all vagueness, obscurity, rhetoric, confusion; to expose incoherence; to arrive, by the use of rational methods, at conclusions acceptable to reasonable and self-critical beings. He believed in this method and defended it, and used it all his life. His purpose was to elucidate and criticise the ideas of those writers who seemed to him to address themselves to problems that were central to men everywhere and at all times. Like Machiavelli, he found a door into a timeless world of the great figures of the past, and questioned them, and sought to understand their basic concepts, their views of man and of society, of what they were and should be. He was never pedantic, and he did not niggle. If the thinkers whom he examined seemed to him dark or confused or even dishonest, he persevered with them if they appeared to him to reveal even glimpses of something important or profound about man’s nature, his goals, or his moral or political experience or needs. And while he found clear writers like Machiavelli or Hobbes or the Utilitarians, if not more congenial, at least easier to deal with, he struggled with formidable and difficult theorists in whom he perceived glimmers of genius – Hegel, Marx and his followers – like Jacob, who, when wrestling with the Angel of the Lord, could not let him go until he had received his reward.

His chapters on Hegel and Marx are among the clearest and most valuable expositions of these thinkers in the English language. He worked on these texts with immense tenacity, reading and rereading, writing and rewriting, paying the most scrupulous attention to the criticisms of friends and colleagues, and was more critical of his own work than others were. When argued with, he held on to his own positions with great stubbornness, but nevertheless went back to the texts and to his own commentaries; if the criticisms appeared to him to have any element of justice, he acknowledged them fully and altered his views; the second edition of his book on utilitarianism contains his own review of the first edition, far more severe than anything said by others. His purpose was not to detect inconsistencies in the thought of others, or merely to expose error, or to interpret, but to achieve at least the beginnings of some vision of the complex and elusive truth which thinkers whom he respected seemed to him to approach from this side and from that. His works greatly added to the dignity of the entire subject in England, and indirectly in every English-speaking country.

He was admired by his pupils, and respected by the most distinguished of his opponents, but he occupied no recognisable position and founded no school. Perhaps this was so because he simply said and wrote what seemed to him to be true, in his own unemphatic, careful prose, with all the qualifications that the truth seemed to demand; he did not modify or shape his thought to make it fit into a system, he did not look for a unifying historical or metaphysical structure, he did not exaggerate or over-schematise in order to obtain attention for his ideas – so that those who looked for a system, an entire edifice of thought to attach themselves to, went away dissatisfied. He had no ambition to shine, or to defeat rivals, or to proselytise or found a movement. He only wanted to discover and tell the truth. His methods were essentially English, and indeed local, characteristic of the Oxford of his youth: but they were superimposed on a temperament and outlook very different from the masters who impressed him, Prichard, Ross and the others.

His view of human nature and its purposes and its potentialities was taken not only from his reading of the classical philosophers, but equally from his upbringing, from solidarity with, and indeed much nostalgia for, his native land, the customs and outlook of that almost pre-feudal community; and also from his lifelong love of French literature and thought, which he found more sympathetic than its English counterpart. He responded to Donne, Herbert, Wordsworth, but the prose of Montesquieu gave him physical pleasure. The French theatre of the eighteenth century – Marivaux, Jean-Baptiste Rousseau, Beaumarchais – moved him to enthusiasm. His letter to a journal defending Marivaux against charges of shallowness and artificiality, and praising him for true insight and exquisite description of the movements of the shy and innocent human heart, was itself a masterpiece of literary sensibility.

He understood best lonely and unhappy thinkers, who showed the deepest understanding of what men live by, and what frustrates them, of solitude and alienation – he loved best of all Pascal, Jean-Jacques Rousseau – solitary thinkers, given to painful moral and spiritual self-inquisition rather than rational self-examination. He praised Proudhon for knowing what the workers, or the petit bourgeois, need, what makes them miserable, because he truly understood them, as the far more gifted Marx, who fitted them into a vast theoretical model, did not bother to do. His acceptance of British empiricism, together with a deeply un-British, romantic vision of the human predicament, imparted to his work a tension that nothing else in English seems to me to have. It was never wholly impersonal: thus, after many pages of sober, Oxford exposition and argument, there would suddenly occur a sharp, original, highly characteristic comment – as when he remarks, ‘Passing from German to Russian Marxism, we leave the horses and come to the mules.’1 In these sudden, often ironical, asides his own authentic voice can be clearly heard. There is something wonderfully fresh, and often devastatingly direct, about these personal passages. Indeed, all his writing was authentic and, as it were, hand-made: it was balanced, unexaggerated, carefully qualified, but nothing in it was mechanical, derived from a model. His books give the impression of being written as if no book on the subject had ever been written before. So, too, with testimonials he wrote for pupils: never overstated, never conventional, they were illuminated by flashes of acute psychological insight, and carried total conviction. It is this first-hand quality that, added to all its other attributes, lends his work peculiar and irresistible charm.

The war interrupted his work. On Lionel Curtis’s advice, he became a member of a somewhat peculiar anti-aircraft battery, which gave full scope for the play of his irony. In time he was transferred to the service of the Yugoslav Embassy, and became a member of the war cabinet of King Peter. He wrote a pamphlet to answer the detractors of General Mihailovic (it was published in a private, limited edition).2 After the war he returned to All Souls as a research fellow and began to produce a series of essays and books on political thought. In 1951 he was elected to a fellowship of Nuffield, and in 1967 to the Chair of Social and Political Theory at All Souls.

He told me that a few years later he was visited by some Montenegrin relatives of his, who were engaged in smuggling, I believe, somewhere in the Balkans. They said to him, ‘You are a Professor at Oxford – that is a very strange thing for a Montenegrin to be doing.’ He added that he thought that they were right. He said he did not feel himself a professor. He found administrative duties a burden; he forced himself to perform them; he attended committees and examined, but without pleasure or satisfaction. He wished to read, to write, to teach. He developed warm personal relations with his pupils; he was an excellent colleague; private life meant far more to him than the busy life of institutions. All Souls suited him better than Nuffield if only because it made fewer demands on his time. He was grateful to Nuffield, which had come to his aid at a difficult moment; some of his closest friendships were made there. Looking after the college garden gave him genuine pleasure. But what he loved best was privacy. He might have agreed with Pascal that all the ills of mankind come because men will not stay quietly in a room.

In certain respects he was happier with Americans than he was with the English: like many inward-looking, reticent scholars he was liberated by the openness, the responsiveness, the warmth, the uninhibited natural candour, the unblasé attitude of American students and colleagues, by the deep and genuine desire for the truth with which they sought for answers to intellectual or political problems, by the fact that they took the trouble to understand what he thought and said. He was particularly happy at Columbia University. Yet during the seven long years of his professorship he longed to be released from it. He was not discontented. Indeed, during his last three or four years, he seemed to me to have grown lighter-hearted, and to have come into something like his own. Friendship, and above all the love and devotion of his wife, were everything to him. He told me that he preferred to live in a village because there relations with neighbours seemed more natural and satisfactory to him – more like the life that human beings have led at all times, everywhere, than artificial existence in an academic enclave.

The heart attack which ultimately proved fatal was the first illness he had had since 1933. He died on 19 February 1975, the very day and month when, fifty-six years before, he had landed at Dover.

His independence, his remoteness from all the least attractive aspects of the life of universities – the idea of trying to involve him in some intrigue was unthinkable – his generous, uncalculating character, his refusal to compromise with whatever seemed to him to distort or ignore or even embellish experience, his distinction as a thinker, his nobility as a human being, were recognised by the academic world here and abroad. He had much pride, but was free from all vanity and snobbery, and treated all men alike: he made no differences between the young and the old, the important and the unimportant, the brilliant and the dull, but behaved towards everyone with the same grave courtesy. He possessed what I can describe only as a quality of moral charm that made all dealings with him delightful. His writings – and this was true of the authors he most admired – were altogether unlike any others. So, in the best and rarest sense, was he.

1 [Oxford undergraduate degree in Politics, Philosophy and Economics.]

1 Consent, Freedom and Political Obligation (London, 1938).

1 German Marxism and Russian Communism (London etc., 1954), 191.

2 The Case of General Mihailovic ([London], 1944).