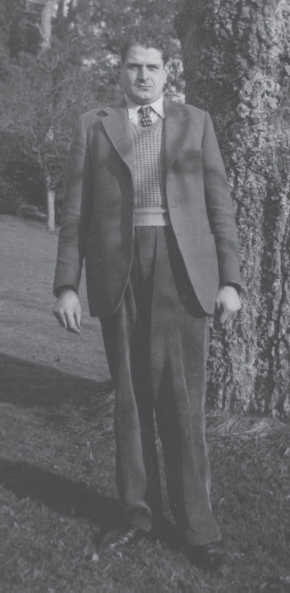

IN THE EARLY SPRING OF 1946, when I was still a government official, I had occasion to go to Paris for a few days, and was staying as a guest in the British Embassy, then presided over by the infinitely hospitable Duff and Diana Cooper. At dinner on my last night in Paris I found myself sitting opposite an officer in uniform, proclaimed by the metal strip on his shoulder to be a member of the Polish Army. He was tall, generously built, with a fine Roman bust and head, looking like (as someone once described him) a kindly Nero. For a Pole, which I took him to be, he seemed to me to speak English with remarkable purity and a rich and imaginative vocabulary; some question on my part about where he had served stimulated him to a magnificent outpouring of words reminiscent in style of an older and more stately world. Although I am far from taciturn myself, I was, for once, perfectly content to listen. The stream of vivid, somewhat formal, eloquence flowed on like a mountain torrent, carrying all before it; at moments it was diverted this way and that by questions or interruptions by the other guests, but not for long: it always returned to its original course, sweeping away, or twisting round, every obstacle in its path, until a full account had been given of the picaresque adventures of his wartime experience.

He continued to talk to me, to my great pleasure, after dinner. Held, like the wedding guest, by this strange and plainly gifted Pole, who plied me with drink after drink long after the hosts had gone to bed, I finally made my excuses and made my way to my bedroom for a few hours’ sleep, until the car that was to take me to Boulogne arrived at five in the morning. This was not to be. My new friend followed, settled himself on the edge of my bed and continued to talk. Some might have found this excessive. I did not; I thought it a strange but delightful experience.

By this time I had discovered that he was Auberon Herbert; that his father had died before he could know him, that he was devoted to his mother and his sisters; that he had joined the Polish forces because he had been rejected on medical grounds by those of his own country. I learnt, too, that he had, not very long before, nearly lost his life in a fracas with some Canadian soldiers, which he described in horrifying detail, mitigated by his rolling Victorian periods. His gift for languages was remarkable: he spoke Polish, Ukrainian, Dutch, as well as French and German, a little Russian (enough to indicate his extreme disapproval of the regime of that country), some Czech, and, of course, Italian, since he had spent many months in his family’s house in Portofino. (He could manage some Genoese and Provençal too.) We turned out to have a good many acquaintances in common, of each of whom he was prepared to provide pungent vignettes; and he judged them by the ancient criteria of the traditional ruling classes of many lands: whether they had courage, moral or intellectual distinction, nobility of character, generosity, personal beauty, charm, breeding, and – most important of all – correct political and religious beliefs. These standards were applied in a confident, direct, unswerving fashion, with fine extravagance of speech and expression. I found that on a good many of our common friends and acquaintances his judgements at times diverged sharply from my own. He listened to my qualifications courteously, but without much attention: everyone he knew had his and her place in the coherent and vividly coloured world constructed by his fervid imagination, which now and again seemed to me to exist at a certain distance from the world of what most of us regard as reality.

This chance meeting resulted in an acquaintance which ripened into friendship. We met occasionally in London and Oxford; from time to time he would invite me (I was then single) to Pixton, but something always intervened. Ten years passed since our first meeting in Paris. In 1956 I married, and that September my wife and I, with some friends, came to stay in Portofino. There we saw a good deal of Mary Herbert and Auberon, who was most hospitable to us all; we greatly delighted in their company. In Portofino even more than in England, Auberon’s quixotic qualities became overwhelmingly evident. He was high-souled and morally fastidious, fearless in his devotion to noble, knightly virtues, and the order in which alone they could flourish, deeply repelled as he was by the modern world, from which he sought refuge in an imaginary older world, to which his social, moral and religious code could be made to apply. Like Don Quixote, he was, above and beyond everything – to use that obsolescent concept – a gentleman. He was totally free from anything in the least small-minded, ignoble, petty, opportunist – anything that in Bloomsbury used to be called ‘squalid’.

His passion for the causes of the oppressed, which he supported in his own exceedingly individualistic manner, seemed to me to stem mainly from his religious convictions, with which his chivalrous instinct was closely inter-woven. Don Quixote may not have achieved worldly success, but his life was nothing if not a triumphant affirmation of the Christian soul in a workaday society. Neither Don Quixote nor Auberon were realists. But then, when men say ‘I am afraid I am rather a realist’, what they often mean is that they are about to tell a lie or do something shabby. From this Auberon was immeasurably remote. Everything that was eccentric and, at times, comical about him sprang from his inability to compromise with the exceptionally ‘realistic’ values of some of the times and places in which he spent his not altogether happy life.

This was very evident in Portofino. The inhabitants of that portion of the Ligurian coast are not given to exaggerated idealism. They are dry-eyed, tough-minded, not liable to excessive compassion, and concerned with their immediate interests, beyond, perhaps, those of other Italian provinces. Auberon was, in a sense, well aware of this – he talked about it often and amusingly, but his penchant for living in an idealised universe led him to magnify the minor intrigues of the inhabitants of this resort, as well as his own relationships with neighbouring landowners and peasants, into dramatic feuds or wonderful alliances, conducted in a world drawn from the pages of Scott or Manzoni or Mary Renault, or at times even from the fantasies of J. R. R. Tolkien, to whose works he was deeply addicted; and this enabled him to live his life at a level at which he could breathe without too much moral discomfort. His vision of life was filled with plots and counter-plots, sinister political conspiracies, secret alliances and mysterious operations of men engaged sometimes in local purposes in Portofino or Genoa or Rome, around the papal throne, or in far-flung worldwide political or financial schemes into which ruthless and wicked men lured innocents to their destruction – schemes which, at any rate at the local Ligurian level, he believed himself able to penetrate and even to foil and turn to his own or other good people’s advantage.

All this was done with immense gaiety, fancy, and sometimes obsessive saga-spinning (which not everyone was always prepared to hear out to the end), but also with a certain unexpected half-awareness of its incomplete reality: moments of fancy (which stimulated some of his ‘business’ activities) were, it seemed to me, succeeded by periods of clear-eyed vision in which he knew that the world, as he described it to himself and others, was not perhaps wholly what he insisted on its being. Heroes and martyrs who had died for his faith populated his world; so, of course, did the oppressed peoples whose causes he took up zealously: Poles, Ukrainians, Belorussians. What the members of these movements in fact thought of him I do not know, but they were fortunate to find someone who was prepared to work for them so passionately, so disinterestedly, and to involve so many of his bemused friends, bemused but loyal to him, and therefore prepared, against all motives of prudence, to be wafted by him into all kinds of unlikely predicaments, on public platforms and stranger places, in pursuit of some usually utopian goal.

Auberon was not only pure-hearted, generous, honourable, and a generator of marvellous Chestertonian fantasies, but warm-hearted, morally perceptive, and always responsive to the states of mind and fortune, the feelings, the moods, the joys and the miseries of his friends. Passionate and unswerving as his political convictions were – no one who approved of the Yalta agreement could be spoken to, at any rate with comfort; as for those who were tolerant of the totalitarian regimes east of the Iron Curtain, they were either fools or knaves and to be treated accordingly – the claims of friendship transcended even these barriers. Although he saw the world politically in terms of black and white, this nevertheless did not blind him to the true character of the human beings he met and came to know. More often than not he recognised honesty, goodness, purity of heart when he met them, however deplorable the political or religious opinions of those who possessed these properties; but sometimes he was deceived, and found his trust betrayed, especially by those he helped, who, at least on one occasion, exploited him shamelessly and used him ill. He bore no grudges and harboured no resentment. He was entirely free from malice and from ill will.

But if my words tend to suggest the character of a remote dreamer, self-absorbed, detached from common concerns, living in a feudal Middle Age of his own, I have failed to convey a true image of Auberon. He was the very opposite of a prig or prude, noble but humourless, not of this world. Unlike Don Quixote, he possessed an acute sense of the incongruous, and, indeed, of the ridiculous, even in his own knight-errantry. He knew that his efforts to be elected to Parliament were not likely to bear fruit, and gave highly entertaining, self-deprecating accounts of his political ambitions and activities. There was a sense in which he knew that he could do relatively little for the Polish or Ukrainian groups which he supported, that a good many of the persons who clustered round him were less worthy than he told himself and others that they must surely be; and that the entire undertaking, however great its moral worth, had rickety foundations in the world of serious social and political action.

It is, perhaps, a property of the romantic temperament to be at once dedicated to pursuing unattainable goals, demanding of the world what it can never give – to develop a kind of spiritual maximalism – and also to remain ironically aware that such claims bear little relation to what can be achieved on earth. It is this that enabled Auberon not to be shocked or offended when he perceived that others, among them persons he liked and respected, stopped their ears to his propaganda, or looked on him as politically inept, whether or not they were personally fond of him, or were touched by his stout-hearted integrity. He was at once prepared to make light of his own endeavours and yet persist with them. The universe of his imagination, the semi-feudal, nostalgic, historical romance which he lived out so movingly, so gallantly and painfully, had become second nature to him, and perhaps, despite moments of penetrating self-awareness – the bitter moments when reality broke through the fantasy – had become one with his basic character and nature.

He was talented, civilised, very well bred, and hated moderation in all things. He was fiercely anti-utilitarian, pursued ends for their own sakes, to extremes, and despised those who did not. He disliked philistines, policemen, cowards and hypocrites more than liars, barbarians or cunning adventurers. More than almost anything he liked style, dash, lunatic courage. He was highly cultivated in an eighteenth-century sort of way. Apart from his gift for languages, he explored byways of philology, preferably of languages and dialects spoken by semi-submerged local populations – Basques or Genoese or Maltese or Lusatian Sorbs, or Dalmatians, or Greek enclaves in Magna Graecia – and had accumulated an extraordinary store of out-of-the-way historical knowledge which fed his past-directed imagination and his acute aesthetic sense. His taste, expressed in the delightful disorder of his life and the charm and distinction of the houses he inhabited in England and in Italy, remained impeccable; so were his manners, whether he was tipsy or sober. He made excellent jokes. Nothing he said could ever make one wince. He was sometimes monotonous and glazed, never embarrassing. He was a loyal and affectionate friend and behaved beautifully to those who worked for him.

His life at Pixton, the management of the broad but not on the whole rich lands which he owned, his country concerns, his hunting and the open-handed hospitality dispensed by his mother – to whom he remained utterly and deeply, perhaps too deeply, devoted – and which continued after her death, not long before his own, were as much as he could do to keep the traditions of an older world going, a world in which he breathed more freely and suffered less acutely. He was visited by a sense of frustration, desolation and, still more, acute loneliness. His faith (if someone as remote from it as I am may speak of it), which was deep, childlike, beset by no genuine doubts, and the supreme value which guided his entire being, preserved him and kept him from ultimate despair. He was, above all, an extraordinarily good man. This shone through everything he did and said. I was not among his intimates, but I knew him, loved and admired him, and mourn his passing, and the world of fantasy which vanished with him.