I FIRST MET MAYNARD KEYNES when I was placed next to him at dinner at King’s College, Cambridge, in the early 1930s, before reading a paper to the Moral Sciences Club. At first he did not speak to me. Then, at the last stage of dinner, when we were eating the sweet, he turned towards me. He asked me, ‘Why are you here? What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I am reading a paper to the Moral Sciences Club later this evening.’ ‘What about?’ he asked. I said, ‘Pleasure.’ It sounded absolutely absurd as I said it. ‘What?’ he said. ‘Pleasure,’ I replied for the second time, and as I did so it sounded even more absurd. He then said, ‘Really. What a ridiculous subject. Now, what are we eating?’ – he looked at the menu – ‘We are eating “potage de something or other”. Why don’t you read about that? Just as good a subject.’ Then a silence. Then ‘What do you think of Whitehead?’ I said that the early chapters of Science and the Modern World seemed interesting to me. Then – a much longer silence. Then ‘I don’t agree with you.’ After which he turned away from me. I did not see him after that for some time.

The next occasion was at the Arts Theatre, Cambridge, in the second week of its opening in 1936, when Lydia Keynes was acting in The Master Builder by Ibsen. Everyone came up to him and said how marvellous she was, and what a superb actress, and that they had hardly ever seen the part better played. I could not bring myself to speak such words because I thought he would see through them: I thought he saw through the others, too. She was wonderfully spontaneous and had great charm on the stage as well as off it. But she was not made to act Ibsen, and the whole thing was to me acutely embarrassing. I said nothing at all. Once again, I got rather a severe look from him.

After that, I met him four or five times in Washington during the war, when we had long conversations, which I found immensely enjoyable. He was charming to me, delightful to be with, indeed literally fascinating, and certainly the cleverest man I have ever met in my life. His intelligence seemed to me uncanny. He knew how one’s sentences would end almost before one began them; his comments were sharp, illuminating, witty, and had extraordinary – unconveyable – intellectual gaiety, sweep and brilliance. At a dinner in the British Embassy in Washington, I was introduced by someone as ‘Professor Berlin’. I said, ‘No, no, I am not a professor.’ Keynes said, ‘And neither am I, and as you may imagine people are always calling me that. When that happens, I invariably say I reject the indignity without the emolument.’ I once asked him for his impression of Lord Halifax, the ambassador. By 1944, they seemed to me to be flirting with each other. Halifax had great charm when he chose to exercise it, and liked Keynes, but I did not know whether the feeling was mutual. I wondered about this and I asked him. He said, ‘Well, I don’t know whether I like him or not, but I find his company agreeable. Not as agreeable as Bob Brand’s1 is, but agreeable. I was particularly pleased when he said to me, “Lord Keynes, I wonder if you would help us. Would you look at a document about economic policy which my party may soon publish? I know that we do not hold the same views, you and I, but why I should like you to read it is because we don’t want to talk rot.” ’ I do not know whether Keynes ever did read the draft Conservative manifesto.

Lord Robbins told me a characteristic story about him. Sir Kingsley Wood, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, died suddenly from a heart attack in 1943. This happened to be at a time when there were informal meetings of the American and British financial experts in Washington. Keynes was head of the British Treasury delegation and Harry Dexter White the head of the American equivalent. Harry White got up at a lunch of the two delegations and said how very distressed his colleagues were at the news of the death of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and that they wished to convey their deep sympathy to the British delegation. Keynes rose to reply, and in his opening remarks said that he wished to thank Mr White for his words, which had greatly touched members of the British delegation, and then said something like this: ‘The late Chancellor possessed one gift which I think that some of the highly intelligent and indeed brilliant people around this table might do well to note and perhaps even strive to emulate. No matter how dark, how tortuous, how complicated and how apparently incomprehensible an economic proposition seemed to him to be, he then had the gift of converting it with a few words into a platitude intelligible to the merest child. This is a great political gift, not to be despised, and some of us round this table could do well to cultivate it.’ Robbins said, I think, that the Americans seemed rather shocked by this: such words when the corpse was hardly cold. It is probable that Keynes meant exactly what he said. The mixture of truth and irony, the wish to épater the solemn, somewhat humourless American officials, was very typical.

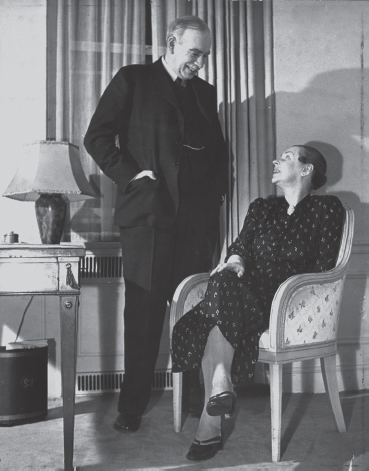

I first properly met Lydia Keynes at dinner in the British Embassy in Washington in November 1944. Maynard Keynes was there for the Stage II negotiations of the Lend-Lease agreement, and it was the night of the re-election of President Roosevelt for his fourth term of office. I was supposed to be an expert in American politics, which I was very far from being, but anyway I was summoned for this purpose, and asked to bring charts which some newspaper had printed as a supplement in order that we might follow the election results in the various States as they were announced on the radio after dinner. It was a small dinner party, so far as I can recollect, consisting of Lord and Lady Halifax, Lord and Lady Keynes, the Social Secretary Miss Irene Boyle, Mr David Bowes-Lyon and myself. I sat next to Lydia Keynes and talked to her in Russian, which evidently pleased her, and she was in a very gay and agreeable mood. She told me about her three journeys in Russia with her husband, and how peculiar these experiences were, and of her curious conversations during one of them, in a sleeping car, with her famous brother, Fedor Lopukhov, the choreographer.

She also said how much she had enjoyed meeting the American Secretary of the Treasury, Mr Henry Morgenthau, who, she said, was very fond of her husband, ‘very fond of Maynar′’,1 as she called him; he hated all bankers, but approved of liberal economists and liked and admired Keynes. One day, when there was some sharp dispute about some monetary problem, she went to see the Secretary of the Treasury in his office, and reported that she said to him, ‘Mr Morgenthau, Maynar′ cannot sleep at night. He says he wants sixpence from you: only sixpence more. Why, Mr Morgenthau, why cannot you give Maynar′ sixpence? I do not know how much money you have, but sixpence is not very much.’ And she assured me that Mr Morgenthau had yielded on the issue, and had given sixpence to Keynes, and had congratulated her on being one of the ablest and most skilful negotiators he had ever met in his life. Her intervention actually had effect. The story is confirmed in a letter from Keynes to Sir Richard Hopkins in the British Treasury, London, dated 6 November 1944, in which he wrote, ‘Speaking of Morgy, Lydia has certainly earned her passage money (let alone her maintenance of my good condition).’2

In this rather happy mood we went upstairs after dinner, spread the various charts on our knees, and the election results began coming in. After we had heard that the State of Alabama had gone heavily for Mr Roosevelt, Lydia began to look bored by the proceedings, and suddenly said to me, ‘Do you like Archie MacLeish?’ (MacLeish was the Librarian of Congress and a poet.) Maynard said, ‘Shoosh, Lydia, not now.’ We went on listening to the results, and after ten or fifteen more, Lydia, who had now become even more restless, said, ‘Do you like the President? Roosevelt? Rosie? Do you like Rosie? I like Rosie. Everybody here likes Rosie? Do you like Rosie, too?’ ‘Shoosh, Lydia, not now,’ said Keynes again. After about another dozen results had come in, she spoke again. She was obviously getting very restive and could hold herself in no longer. She turned to me again. ‘Do you like Lord Halifax?’ The ambassador was sitting about a yard from me at the time. I was speechless, and produced a neighing sound, I think. Nobody (save the radio) uttered a word. Keynes did not shoosh her this time, but stared in front of him with a faint smile on his lips and with his long fingers pointed together upwards. Lord Halifax looking faintly, very faintly, embarrassed, rose from his place, patted his little dachshund, called Frankie, and said, ‘I don’t think that Frankie is very interested in these goings on, you know. I don’t think she is very politically-minded. I am going to find out from Harry Hopkins1 what the position is’, and he strode out of the room. He came back a few minutes later, and said, ‘Harry says it’s in the bag’, after which we left.2

I never met Keynes again. He died less than two years later. But I had several very enjoyable meetings with Lydia, in London, in Cambridge, in Sussex. She talked with great animation about Diaghilev, about the great ballerina Galina Ulanova, about her feelings about Bloomsbury. But I have no clear memories of that now.

1 Principal representative of the British Treasury in Washington 1944–6.

1 [i.e. her pronunciation of his name ended with a soft Russian ‘r’, the Russian soft sign ь being indicated by ′.]

2 The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes (135/79) xxiv, Activities 1944–1946: The Transition to Peace, 161.

1 28/1.

2 [IB told a variant of this story to his biographer Michael Ignatieff – op. cit. (xvi/1), 127–8 – adding: ‘Naughtiness Keynes rather liked, especially against he pompous’ (interview with Michael Ignatieff, 5 June 1994: Wolfson College, Oxford/Sound Archive, British Library).]