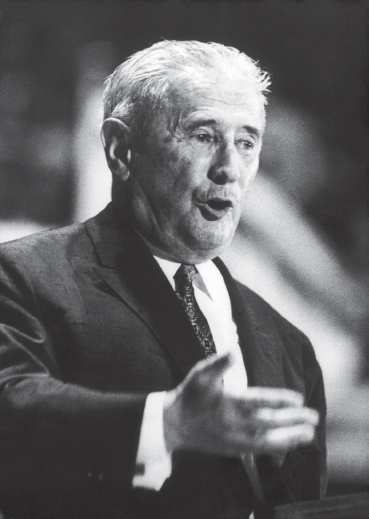

I FIRST MET NAHUM GOLDMANN1 in Washington in, I think, 1941, when I was a temporary wartime official of the British Ministry of Information. Chaim Weizmann, when I told him in London that I was being posted to the USA, said he would write a letter to ‘Nahum’, who, he assured me, was excellent company, likely to raise one’s spirits during the darkest hours: 1941 was indeed an exceedingly dark hour, and Nahum did have the predicted effect. His unquenchable appetite for life in all its manifestations, his perpetually active intelligence, his apparently inexhaustible fund of recollections of men and events, his descriptive powers, his highly infectious sense of the ridiculous both in situations and in the characters and relations of individuals, his total lack of pompousness, his wit, quickness of perception, great charm, his sheer vitality, could not fail to raise one’s morale.

During my years in the British Embassy in Washington he occasionally called on me, usually after a visit to some member of the diplomatic mission – William Hayter or John Russell, with whom, as head of the Jewish Agency office in the USA, he found it useful to keep in touch, and who in their turn found him agreeable, intelligent, well-informed and highly exhilarating. Of all official Zionists – to whom the attitude of the British authorities was, to say the least, ambivalent – he was the least unwelcome representative: his good sense and moderation shone through everything he did and said.

Zionists were in general thought of by the British missions as at best embarrassing allies, more often, in view of the 1939 White Paper policy, as tiresome critics and sources of unfriendly comment in the American press, although not as influential as pro-Irish or pro-Indian groups. Hence the reasonable tone and content of Goldmann’s interventions were greeted with some relief. He had his own emotions under control, and he possessed then and later (and no doubt earlier too, before I knew him) a singular capacity for understanding the minds of others – the rational and irrational foundations of their opinions, the pressures under which they were working, the limits within which they were compelled to operate. He possessed that politically invaluable power of empathy with both friend and foe, and spoke and acted accordingly.

Goldmann was a born diplomat and negotiator: not on the same level as, or with the immense world authority of, a statesman of genius like Weizmann, but at the more workaday level of middle officials, whose influence and goodwill are, if anything, sometimes more important than those of politicians and heads of State. He was, all his long life, as deeply committed to the Zionist cause as any of the leaders of the movement – his faith and loyalty to the movement remained absolute – but he possessed a firmer grasp of reality than the majority of them, and far more tact. It was these qualities that enabled him, by indirect means, to keep President Roosevelt from exploding under what he regarded as the provocative behaviour of the extreme Zionists in Washington in the later years of the war. Goldmann realised only too fully what effect such a revulsion of feeling on the part of the understandably idolised leader of the democracies – a hero to most American Jews – might have had on Zionist fortunes.

It was he, again, whose statesmanship prevented a breach between the Zionist leaders and President Truman in 1946; he displayed not only skill and rare persuasive powers, but political courage, in promoting the Reparations Agreement with Chancellor Adenauer, which led not only to compensation of individuals robbed by the Nazi regime, but to massive economic aid to the State of Israel that proved crucial to its physical survival under attack by its enemies. Goldmann was not unaware of his own talents: as a gifted journalist (he had written articles for a Jewish journal in Germany as early as 1910, and had spoken on Zionist platforms at the age of fifteen), as an organiser, as a man of European as well as Jewish culture, and exceptional sagacity. His masterly critical surveys of the state of the Jewish people in the world – tours d’horizon – were the most brilliant since those by Max Nordau. His speeches and writings were a unique contribution to Jewish self-awareness, to the awakening of a good many sleepers to their true social and political situation. He possessed an exceptional capacity for theoretical formulations – for defining political and social issues and proposing realistic measures for applying his ideas to practical matters.

Yet he knew himself, and often said in his speeches and writings, that these were not – indeed were incompatible with – the qualities of character needed by the radical transformers of society, great revolutionaries, pioneers and creators of new forms of human life, whether for good or ill: these must be dominated by a vision that radically simplifies – oversimplifies – the complex texture of reality. Intent with all its force upon its goal, it ignores – or if it catches a glimpse, closes its eyes to – obstructions, possible dangers, looming obstacles (Goldmann called it a kind of necessary blindness), and so avoids the onset of the fears, doubts, hesitations which a more sober, more realistic, more sensible approach must inevitably generate. He saw clearly that if Theodor Herzl had not possessed this capacity for not seeing the odds against him, or if Ben-Gurion had foreseen some of the difficulties that the creation of the State of Israel in the midst of violence was liable to cause (as, say, Sharett or indeed Weizmann probably anticipated), they might have been paralysed – or at least might have become incapable of that overwhelming force of will by which they were, in fact, driven; nor without it would Churchill, perhaps, have been able to save Britain as he did. That indeed is why Ben-Gurion’s modern heroes were men who resisted what seemed irresistible force: Churchill, Tito and, at least until the Six-Day War, de Gaulle.

Goldmann knew himself not to be cast in that mould. He admired these heroes and recognised their value: but he also knew that some of the obstacles which those great men ignored do not always go away; and he stressed the conditions necessary to the peaceful existence required for Israel’s survival and progress. In and out of season he preached – and caused his followers in the World Jewish Congress to support – a programme based on three cardinal policies which Israel could ignore only at its peril: to integrate itself into the Middle East, that is, to achieve recognition by, and peace with, its Arab neighbours; to obtain a measure of goodwill from other nations; and to secure unbroken support, both spiritual and social, from the Jewish Diaspora. He realised, as a corollary of this, the need for a proper attitude to the issue of double allegiance, which he recognised as a genuine problem to be faced and solved, not put out of one’s mind.

His steady insistence on the need to pursue these goals often made him exceedingly unpopular: it was probably as responsible as anything for his exclusion from the governments of Israel. There were also other reasons for this: he was considered to be, and was, a man much addicted to such pleasures as the world could offer. He had an immense love of life, he enjoyed the society of artists, intellectuals, pretty women, men of power and influence, for their own sakes. His devotion to Judaism, its past and present, remained constant. He carried his Jewish learning – greater, I suspect, than that of any other secular Zionist – lightly. But then he carried everything lightly: he lacked solemnity, he did not display gravitas; it was that that made him so amusing and stimulating a companion.

One of Aristotle’s doctrines in his Physics is that some bodies possess the quality of weight, others possess the quality of lightness. This doctrine, as it turns out, has no relevance to the material world; but psychologically there is perhaps something in it. Some men possess natural moral or spiritual weight: Goldmann was characterised by the opposite – lightness, a tendency not to take things to heart for too long, not to have a tragic sense of life, not to impose his own authority or that of some dominant Weltanschauung (in a sense including that of an inner vision in the creative depths of a lonely thinker’s introspection) on other, lesser, men. He did not wish to bend others to his will. He was compounded of lucid intelligence, a very great deal of good sense, acceptance of life with all its oddities, and an exceptional capacity for sheer enjoyment. He was not given, in my doubtless fallible view (it is a great arrogance to pretend to be able to see into the souls of others), to being tormented by agonising alternatives. He lived his life comfortably, easily, sensibly, and gave a great deal of pleasure to others. In the tense, somewhat puritanical, often stern atmosphere that tends to surround the creation of new societies, with its calls to heroism and sacrifice and martyrdom – as was the case with the rise of Israel – such characteristics are liable not to be highly rated. Goldmann was thought not weighty, not morally serious, enough: too hedonistic, too flexible, too adaptable, too light in the hand. This is intelligible, but was not entirely just: his convictions were both deeply thought out and deeply held, and, in my own view, for the most part valid.

He said as early as 1921:

We are very much concerned about the sympathies of this Lord or that. But somehow no one seems to be worried about the one factor which should be more important to us than the attitude of all the Lords and baronets put together; that is, how the Arabs feel about us. It seems that the question whether the Arabs regard us as friends or foes, whether they trust us or fear us, is of concern only to a few young dreamers and malcontents [he was twenty-six] who have been harping for years on this basic shortcoming in our political programme.1

He was preoccupied with this issue – as any realistic Zionist might be – all his life. He knew by 1937 that, given ‘the ways of extremist and aggressive nationalism’ which ‘the Arabs have learnt from Europe’,2 a bi-national State was impracticable. He felt sure that the way of power politics was not Israel’s way forward: ‘Israel lives in the Middle East and it cannot live there for ever as a fortress, politically, militarily or spiritually. If we did not want to live among the peoples of the Middle East, we should have gone to Uganda and not to Eretz Israel.’3 Hence his proposal that Israel should have been neutralised, like Austria or Switzerland, the inviolability of its frontiers guaranteed by the Powers, as theirs are; this would have freed its Arab neighbours from the fear of Israeli imperialist expansion, and it would have the advantage of Israel’s not being represented in the United Nations, and so being freed from having to take up positions on the conflicts of other nations. This idea, which now seems utopian, was, perhaps, feasible when Goldmann originally conceived it. I have never understood why it has been regarded as absurdly unrealisable.

However that may be, Goldmann was indefatigable in protesting against overweening national pride – against aggressiveness, faith in power alone. He tells us that Ben-Gurion argued against him that peace with the Arabs, Palestinians or others, was not attainable in this generation: the Arabs looked on Jews as people who had robbed them of their ancestral land; hated them too deeply to consider the remotest possibility of coming to some genuine agreement with them, no matter how flexible Israel was, compatibly with its own minimum security requirements; and that consequently the survival of Israel did, however sadly, depend on force; and therefore remained precarious. Goldmann understood this. None the less, he thought that some concessions could be made: that evidence of peaceful intent, of a deep and sincere desire to be a Middle Eastern nation among its neighbours – and not a permanent outpost of an alien Western culture – could have been, and still could be, effective.

The leading ideas of the Peace Now movement – although, so far as I know, he had no connection with it – were close to his heart; he thought that unless one worked for what seemed impossible, the future of Israel would be too uncertain; that if Herzl had not worked for the impossible, Zionism would have remained stillborn; that if one knew what kind of society one believed in, simple realism dictated that if one persisted, one might get somewhere – at any rate somewhere nearer one’s ideal than by sheer dependence on armed force and American support, however indispensable these might be for immediate survival.

He seemed to critics too gullible: he believed in the value of conversations with what Weizmann used to call ‘moderate opponents of Zionism’; his view that because the Soviet ambassador in Washington singled him out as a man to talk to, business could be done with the Soviet Union, seemed to them then (and seems now) remote from present-day reality (or even that of the earlier hours of tomorrow). On this they may well be right. But this inclination to accept various devils’ invitations to supper, while it argues a certain degree of vanity, and excessive faith in his own powers as a negotiator in the most unpropitious conditions, does nothing to invalidate his basic theses. He was convinced that it was unwise to flout the opinion of people who have wished Israel well in the past, and could do so again. He believed that justified pride in victories over the Arab enemy, in wars for the most part forced on Israel, could nevertheless go before a fall, and that the transformation of Israel from a hemmed-in, encircled, endangered State into a nation seeking protection principally in military strength could not be a healthy development – equally distant from the dreams of Herzl and Pinsker, Ahad Ha’am, Weizmann and Sokolov, and the founding fathers of the Yishuv, whatever their differences. He deplored the tendency of some among the latest Israeli generation to think of their past as a heroic tale from Bar Giora and Bar Kochba to Trumpeldor and the Haganah, with the intermediate centuries of the Diaspora – and still more the Holocaust – struck from the record as painful and squalid servitude and martyrdom, to be expunged from the national memory of a proud, self-reliant, free people. He held that this attempt to forget the painful past was a form of barbarism, because men should know whence they originated and how they have come to be as they are.

He said that those who died for their religion, or because they chose to live as Jews, were no less heroic than those who fought and died for the State of Israel. And he denied the doctrine that only by becoming Israelis could Jews expect to enjoy full human rights, civil liberties – and consequently was wholly opposed to the view that claims to these rights in the lands of the Diaspora must necessarily come second or third after the obligation to the State of Israel on the part of the Jews of the Diaspora. This, for him, was a denial of the whole of Jewish tradition, the Torah, the prophets, the Babylonian Talmud and its interpreters, the Spanish period – unacceptable to free men, historically, ethically and politically.

All this Goldmann believed and preached, and thereby incurred attacks for insufficient enthusiasm for, or lack of loyalty to, particular policies of Israeli governments and of the more nationalist Zionist leaders. Perhaps if his anxieties had been more agonised – like those of Ahad Ha’am or Einstein, or of Weizmann in the last ten years of his life, or of the more ferocious opponents of Herut or the Gush Emunim – he would have seemed a more formidable figure. He could not convert himself into an angry prophet: he loved pleasure and comfort and delighted in human variety; he remained calm, reasonable, tolerant, civilised, a friend to all the world, prepared to listen to almost any sensible person. Perhaps he was a little too kindly and easygoing, gave himself too freely, at times, to people of no great worth, was too ready to skim happily on the surface of public life.

He was a man of unswerving dedication to the original ideals of the movement for which he worked all his long and useful life. He performed notable services to Jewish self-knowledge. But his greatest merit, and his principal claim to be remembered when the present day is over, is that by and large, and often against the main currents of Israeli Zionist opinion, on the main issues of the deepest concern to him and us, he was, and will eventually be seen to have been, fundamentally much more right than wrong.

1 1895–1982.

1 Nachum Goldmann, ‘Politik ohne Reserven’, Freie zionistische Blätter no. 3 (July 1921), 36–49 at 39. Quoted from an English translation of excerpts, ‘Have We Learned Our Lesson?’, in Nahum Goldmann, Community of Fate: Jews in the Modern World; Essays, Speeches and Articles (Jerusalem, 1977), 6–8 at 7.

2 ibid., ‘Partition: A Jewish State in Part of Palestine’ (1937), 12.

3 ibid., ‘The Jewish Spirit of Israel and the Diaspora’ (1965), 36.