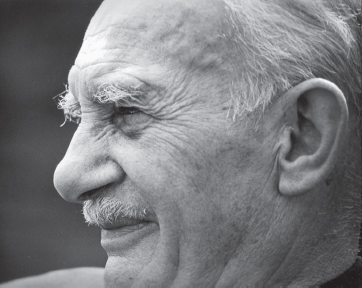

Martin Cooper in 1980, aged 70

MARTIN COOPER WAS ONE of my oldest friends. From the beginning there was a natural bond of sympathy between us which never grew weaker, and made communication between us, at all times, easy and usually exhilarating. I remember our first meeting: it was in the spring or summer of 1930 (or 1931) in the anteroom of the Holywell Music Room in Oxford, after a recital of his own piano works by the now largely forgotten Russian composer Nikolay Medtner. We walked away together and discussed the quality of Medtner’s music, the possibility of the influence on him of Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, the social views of Russian composers at the beginning of the twentieth century (I remember that one of Medtner’s works was called Ode au travail, which seemed to indicate vaguely socialist sympathies). Then we talked about contemporary English composers, about whom Martin tended to be moderately critical. I thought I had never before met so spontaneous and fascinating a talker, with so wide and lively an interest in the European art and culture of our time. We agreed to meet again, and so began a happy personal relationship which lasted to the end of his life.

His friends, I discovered, were some of the most original and celebrated figures in Oxford – Maurice Bowra, John Sparrow, Goronwy Rees, A. J. Ayer, Alan Pryce-Jones, Duff Dunbar. Martin had been educated at Winchester, but there were not, it seemed to me, many Wykehamists among his friends – John Sparrow was one, but apart from him I knew of no schoolfellow of his who could be described as an intimate friend. One spring vacation – it may have been in 1931 – he invited me to stay with him at his parents’ house in York. His father was a canon at the Minster, a charming, gentle, welcoming host; his mother a rather more formidable and firm figure, who seemed to me to dominate the household. I stayed for about a week. In the evenings I tried to read philosophical books as part of my academic course. The old canon would come up to the chair in front of the fire in which I was sitting, look over my shoulder, look at my worried expression, and ask ‘Stiff?’ ‘Yes,’ I would answer, ‘very.’ He would shake his head in sympathy and pat me gently on the shoulder. Martin and I went for walks in York and its environment; I remember he took me to a tea shop near the Close, which entertained its customers with some kind of forerunner of the jukebox – when I put the relevant coin in it, it played the Dance of the Seven Veils from Richard Strauss’s Salome. I don’t know why, but I thought it curiously incongruous in those clerical surroundings, for all its biblical associations. Martin thought it would do the pious nothing but good.

Martin Cooper in 1980, aged 70

In Oxford I saw a good deal of Martin. He had plenty of time to spare: he was not a particularly assiduous student, and, after failing in some examination, was requested to leave Hertford College, of which he was an undergraduate, and migrated to St Edmund Hall, which was more tolerant of lively academic dilettanti. His company was a source of endless pleasure to me: he was spontaneous, affectionate, imaginative, gifted, amusing, with an acute and often ironical interest in the characters or peculiarities of human beings, in literature, in the arts, in, so it seemed to me, every aspect of the life he led, or that of writers and composers in whom he took an interest. He was infinitely gay and responsive to both ideas and works of art, and reacted to them at once more impulsively and more intelligently than most of our common friends.

After he took his degree I did not see him for a year or two. I knew that he had gone to Vienna and had become a student of the head of the conservatoire in that city, the celebrated teacher and composer Egon Wellesz. When Wellesz, who was by origin a Jew, was driven out of Vienna in the later 1930s, Martin had a large part in getting him domiciled in England – Wellesz spent most of his remaining years, contentedly enough, I thought, as a greatly respected fellow in music of Lincoln College, Oxford. Martin remained attached to him, and learnt a great deal from him about out-of-the-way subjects in which he delighted – the music of early Ethiopian and Armenian churches, the influence of Venice upon the Armenian church in that city and vice versa; the development of atonalism in Vienna, and its musical politics and its impact on composers; and, in addition to this, much solid learning. I remember meeting Martin at the Salzburg Festival in, I think, 1934, armed with sheets of music paper on which, he told me, he proposed to inscribe four songs which he had composed, somewhat in the style of Schumann, but very different from him too. At that time he wished to be a composer and a pianist, and it was only after he had convinced himself that his work in both these spheres did not come up to his unshakeable critical standards that he abandoned this for the history and criticism of the work of others.

I saw him on and off in London in the 1930s – he came to stay in my parents’ house once or twice, and, as before, we talked about everything in the world. One of his remarkable attributes was his understanding, both intellectual and intuitive, of what a culture is, and what the impact of one culture on another could generate. He understood, and could discuss vividly and with accurate knowledge, the impalpable relationships of art – music, painting, architecture – to social outlooks, ways of life, philosophical trends, and above all the literature, both imaginative and critical, of a given form of civilisation; and, of course, of religion – its ritual, its institutional life, inner spirit, mythology, tradition, which had entered so deeply and inevitably into the European consciousness and creative activity in every sphere, from the earliest days. His deep and sensitive grasp of the strands that bind together different aspects of the life of a given society at some particular stage of its development was something that not many musical critics of his time, at any rate in England, have, or want to have. It was this that enabled him to say and write such illuminating things about, say, the connections of the opera to life of the seventeenth- or eighteenth-century courts, to the literary forms chosen by the librettists, about the effects of patronage on artists, the influence of movements of social revolt or bold, new intellectual ideas on the music composed by the creators of the operatic tradition. I had never heard these topics more brilliantly and attractively expounded than in his conversation directed at increasing my understanding of these things.

Even then – in the mid 1930s – it was plain that what attracted him most deeply was the music (and literature) of Latin countries, particularly France and Italy. His interest in Eastern Europe, especially Russia, developed somewhat later. Martin was, of course, steeped in the German musical tradition (as what writer about music cannot afford to be?), but French eighteenth-century opera fascinated him more than anyone else I know – it was from his lips that I heard such names as Philidor, Monsigny (and much about them), and not only those of Rameau or Gluck; and then of Paer and Méhul (who else at this time could have discoursed on his unperformed Agar au désert, or compared La Journée aux aventures to Le Sueur’s La Mort d’Adam et son apothéose?). It was all far more interesting than anything by Romain Rolland. He adored Berlioz, when not so very many people in England took an interest in him, and spoke of him as a composer whose music possessed magical qualities, who entered realms not traversed by others. He loved Opéra comique as such, on which he wrote, as we all know, excellent studies, both in books and in articles. He adored Verdi, too, and once said to me that he would come from the depths of China if there were a Verdi festival anywhere in the world, whatever the distance.

Needless to say, he profoundly admired the great German masters (his book on Beethoven is evidence enough of that), although he remained somewhat cool to Wagner, and to Schoenberg and serialism. I did not know anyone else in England who spoke so eloquently and, to me, convincingly, of the beauties of Boieldieu, Auber, Meyerbeer, and of course Gounod, but above all Bizet (on whom he wrote an excellent monograph), as Martin. He loved Fauré, Debussy, Ravel – the French ‘silver age’ – and the minor deities too – Chausson, Roussel, d’Indy. He shared my dislike for César Franck (‘the salacity of the organ loft’, he once said of him) and Florent Schmitt. He did his duty to British composers in the British Council booklet – and said that if Vaughan Williams had been called Vagano-Guglielmetti he might have had a better press in Europe. Although his musical heart remained in France (when it did not wander to Russia), he thought that the new generation of British composers was seriously underestimated in that country. I did not see a great deal of him in the immediate pre-war years. I read his musical articles in the old London Mercury, the Daily Herald, the Spectator, and we exchanged occasional letters. During the war I was in Washington and Moscow on government service, and it was only after I returned, in 1946, that he told me that he had been received into the Roman Catholic Church in the first year of the war. I remember telling him that the Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain had once told me that he was converted because he found himself on a path which led unswervingly towards the Church, that he felt no sense of relief by becoming a Catholic, but that he could not do otherwise: Martin said that this was not dissimilar from his own condition, but plainly did not wish to discuss this further, at any rate with me.

It seems to me unforgivably arrogant to pronounce on the source or, indeed, nature of another human being’s spiritual experience, however well one may believe that one understands it. I go no further than to advance, most tentatively, that Martin’s deep understanding of the Western cultural tradition, especially in France and Italy, in which the ritual, institutions, faith, moral and metaphysical ideas of the Roman Church played so central a part, had something to do with his conversion. It may have been in reaction to the somewhat chilly Protestantism of the north of England into which he had been born, and from which he recoiled aesthetically, and ethically too. His conversion lost him some of his militantly anti-clerical friends, but our friendship remained undisturbed.

One of the links between us – not that we needed it – was our common friendship with and admiration for Miss Anna Kallin, a most remarkable woman who from the beginning had shaped and developed the talks department of the new Third Programme of the BBC, encouraged by her director and lifelong admirer, Sir William Haley. Miss Kallin was Russian, brought up in Moscow, and had spent many years in Berlin. She was a many-sided, highly intelligent woman with a sharp sense of humour and immense culture, lively, amusing and amused, with an exceptional gift for discovering and eliciting broadcast talks from some of the most talented members of the young post-war generation. Her services in raising the intellectual standards of her adopted country are, even now, not sufficiently recognised.

She and Martin took to each other instantly: she took his advice on musical matters, and it was she, perhaps, who awoke his interest in Russian music, which had always been there but became pronounced in the last decades of his life. He learnt Russian, became progressively more and more fascinated by Russian thought, literature, particularly poetry, and towards the end of his life published a brilliant translation of a Soviet book on Stravinsky. He told me that while he owed most to Anna Kallin, he profited a great deal from conversations, much earlier in his life, with such experts on Russian music as M. D. Calvocoressi and Gerald Abraham; his expertise in this field is evident in his book of essays Ideas and Music,1 as well as in articles in the Spectator, in the Musical Times, of which he became the editor, but above all in the Daily Telegraph, where he succeeded Richard Capell as principal music critic in 1954. Miss Kallin had opened certain doors to him, and the devotion and concern for her welfare of himself and his wife Mary did a very great deal to preserve her in her decrepit and lonely old age. To see them together was a great pleasure; intellectual gossip, endless dissection – sometimes mocking, at other times affectionate and admiring – of the personalities and motives of others, free play of irrepressible ridicule of anything that seemed pompous or pretentious or silly or philistine (there had been a good deal of opposition from such quarters to Miss Kallin’s unyielding standards) made their association a source of delight to their friends and themselves.

At some point in his later life Martin’s religious orthodoxy melted away; he did not speak to me of it directly, but when I said one day that I thought that perhaps Dom Lorenz Perosi was the last true Church composer, and compared him to Messiaen, he said, ‘I must tell you that I no longer believe.’ That was all; it was plain that he did not wish to be questioned on the matter. I have learnt from his daughter Imogen that in his desk were found passages of poetry – free translations from the Italian of Leopardi, the Spanish of Machado, the French of the Rumanian Petru Dimitru – which had meant much to him in his last years. They have in common a noble despair, a painful acquiescence in the face of vast, irresistible, unintelligible forces, a longing for the dark path which leads into the night, to le néant – a welcome guest, as in Lensky’s aria before his death in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, or Heine’s poem set to music by Brahms:

Der Tod das ist die kühle Nacht

Das Leben ist der schwüle Tag.1

The Russian poem, much loved by him, which Martin asked me to read at Miss Kallin’s funeral has some bearing on this.2 They might both have agreed with the Russian writer Alexander Herzen, who said that art, which resists decay, and the summer lightning of happy love, are all that we can cling to in our lives, which apparently lack all meaning and purpose.

In our relationship he continued to the end to talk with unique charm and animation about people and things. His critical judgment, his wit, his generosity of spirit were undimmed. His loss of faith and the dark metaphysical questionings did not, it seemed to me, diminish the sensibility with which he responded, often passionately, to anything that seemed to him to possess artistic vitality, to the great monuments created by human genius, to anything that resisted the forces of barbarism and destruction.

His friendship was one of the great blessings of my life, and I shall never cease to mourn his passing.

1 [London], 1965.

1 [‘Death, that is the chilly night / Life is the humid day.’]

2 [Possibly Pushkin’s ‘Ya vas lyubil’ (‘I loved you once’, 1829), which, Martin Cooper’s daughter Imogen tells me, her father did love and talk about. Ed.]