YITZHAK SADEH IS TODAY chiefly known as one of the heroes of the Israeli War of Independence. This is doubtless his chief claim to immortality, but his earlier life was so unusual and filled with such peculiar contrasts that its claim on our interest is scarcely smaller.

His father, Jacob Landoberg, was a rich merchant, a man of considerable charm, vitality and sense of pleasure, and a deeply sensual nature, which made the confines of an orthodox Jewish marriage intolerable to him, with the result that he left his wife Rebecca, the handsome, opulent-looking daughter of one of the most celebrated and saintly rabbis of his time, idolised by his community in the city of Lublin in Russian Poland, and led a feckless, unhappy but not uninteresting life, in the course of which he scattered his originally considerable fortune, and, it is said, died in poverty and illness.

His son was somewhat spoilt in childhood, grew up as a rich, good-looking, physically well-developed, precocious boy, adored by his mother, and determined, as soon as he reached maturity, to break away from the suffocating atmosphere of philistine respectability and conventional religion in which prosperous middle-class Jewish families then lived, and their deeply provincial outlook: against these restrictions he spoke with vehemence for the rest of his life.

Isaac was a wayward, obstinate, strikingly handsome young man. He obtained a normal Russian school education, but refused to go to university, which appeared to him to be a waste of his talents.1 In sharp reaction against what was in effect the vast ghetto in which the Jews of Russia were then confined, he developed a fanatical passion for physical self-improvement. He became a boxer, a wrestler and, what was very rare indeed in Russia at the turn of the century, a passionate footballer, who played the game as often as he could, taught it to others, and became a notable sporting figure in his (and my) native city of Riga.

Riga at this time was a city largely dominated by German culture, which derived both from the Baltic barons, who owned vast estates and formed a solid and fanatical caste of servants of the Russian monarchy, and the solid German middle class, which in Riga created an outpost of German nineteenth-century culture, a German opera, a German theatre, and a nationalist outlook directed against all efforts at assimilation by its Russian overlords. At the bottom of the social hierarchy were the original natives of the country – the Letts, a severe, industrious, oppressed population of Lutheran peasants, who at this time began to generate the beginnings of an intelligentsia, and were making strides particularly in the graphic and plastic arts. In the interstices of this social structure was to be found the small official Russian establishment which governed the Baltic provinces, and finally the Jews, who were divided into the upper stratum of those whose language and habit were German (together with some surviving descendants of the community of pre-Petrine Swedish times) and the lower stratum of the mainly Yiddish-speaking Russian Jews, whose children spoke Russian and were moving in the main directions which divided Russian Jewry at that period: liberal bourgeois, socialist and Zionist.

Isaac Landoberg, we are told by his nearest relations, looked upon all these movements and strata of population with equal contempt. He was filled with the romantic ideal of personal self-realisation: this took, in the first place, the form of physical self-perfection; that once achieved, he turned towards moral and intellectual self-education. He cut himself off from his parents, who were by this time divorced – he despised his mother’s second husband, Isaac Ginzburg, and hardly ever spoke of him – and with such money as his father had left him, determined to make his own life and career. An expert in nothing save boxing, wrestling and football, he was too lazy and too bohemian by nature to wish to acquire any kind of professional skill. Consequently he decided to become an art dealer – this would shock his milieu, and afford him an opportunity, as he supposed, of a free and imaginative life, meeting painters and sculptors and other free spirits and living an independent, gay and, above all, gentile life, free from the cramped, over-intellectual, orthodox life of the Jewish merchants and scholars of whom his family was composed.

His mode of life was extraordinary: his shop remained closed in the mornings, which he devoted to boxing, organising football matches, wrestling and posing as a model for painters and sculptors. He was proud of his appearance, and the fact that his well-built body at times attracted the interest of some of the young naturalistic painters and sculptors who were then to be found in Riga flattered him greatly, and he took pleasure in the thought of how profoundly outraged his mother and relations would be by accounts of this pagan activity. He had read Nietzsche and determined to cultivate the Dionysiac side of his nature. Sexually he seems to have been perfectly continent at this period, although later he was to become a lover celebrated for his infidelities.

In 1912 he married my father’s sister Evgenia (Zhenya) Berlin, his first cousin: their mothers were sisters.1 This lady, the very opposite of Landoberg in every respect, a socialist who proposed to devote her life to the improvement of the lives of workers and peasants, a graduate of two faculties, humourless, earnest, respectable, idealistic, without any feminine attainments, exceedingly plain, with a cast in one of her eyes which gave her a peculiarly governessy appearance, fell passionately in love with the splendid savage whom Landoberg delighted to impersonate. He did not reciprocate her passion, but was impressed by her intellectual attainments, by the fact that she had braved the anger of her parents and respectable friends by taking part in the revolutionary activities of 1905, that she was sought after by the police for two years; consequently he permitted her to marry him. The wedding, which relieved their common relatives by its respectability, was celebrated in the best bourgeois style at an immense party at which the bridegroom became somewhat intoxicated, to the mingled horror and pride of the bride. The life of boxing, wrestling, art dealing continued until 1914.

As soon as war broke out Landoberg immediately volunteered for service in the army. As he was an only son and a married man it was not legally necessary for him to become a soldier: his rich relations promptly bought him out of the army. He allowed himself to be brought back to his doting wife and child, a daughter called Asya; after a few weeks of tranquillity he deserted his wife and secretly joined the army again. He was ‘bought back’ again. He did this for a third time and disappeared – his relatives were discouraged by the two earlier flights and ceased to trouble about him.

In 1917 he appeared in Petrograd as a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, dedicated to the peasants’ cause, armed with an enormous Mauser revolver and an armband proclaiming him to be a member of the People’s Militia. He was at this stage filled with revolutionary zeal and childish pride in his new uniform, his pistol and the intoxication of the Revolution. He appeared in the Petrograd flat of his very respectable brother-in-law and cousin, Mendel Berlin, and his wife Marie – my parents – and boasted about his revolutionary exploits with such innocence and charm, such infantile delight in the violent upheaval then in progress, that he enchanted us all. His hostess, also a cousin, took his revolver away and plunged it in a bath of cold water as if it was a bomb which might go off. He allowed himself to be disarmed and sat in our flat till three or four in the morning regaling his goggling relations with his own and his comrades’ exploits as heroes of the Revolution, under the ultimate command of Pinchas (in those days Petr) Rutenberg, whose view of Lenin and Trotsky he shared: he told us, I remember, that they were a couple of dangerous fanatics and should be suppressed. His wife took a more serious view of events, but allowed herself to be carried away by his exuberance and his utter unconcern and irresponsibility.

He was a man of considerable temperament, a gifted actor, and a great wooer of others, particularly women. He was followed by adoring ladies and addressed revolutionary meetings, although those who heard him could never remember anything in particular that he said. He was a natural orator, fiery, convinced, rhetorical and inspiring: with this went a quality of gay and cynical frivolity, not unlike that of the greatest of all Russian revolutionary tribunes, Mikhail Bakunin, in the nineteenth century. Like Bakunin, Landoberg was fundamentally a pleasure-loving anarchist, irked by all ties and frontiers, heartless, as innocent children are heartless, in pursuit of some goal on which he has fixed his fancy, but, like a child, naive, transparent and affectionate.

He stormed round Petrograd in 1917, and probably effected nothing. After the Bolshevik Revolution he disappeared again. For some months his wife had no idea where he was and had to be supported by her relations. He left her with no means of subsistence and appeared to take not the slightest interest in either her or his child. He was subsequently discovered to have joined the Red Guard – simply from love of action, as he later told me – and to have wandered about with his detachment in central and then southern Russia. Then he reappeared in Petrograd, went to see his wife in Moscow, where by this time she was living with her brothers; she was overjoyed to see him and asked no questions – he showed concern about his child’s illness, but almost at once disappeared again, promising to come back very soon. He duly deserted the Red Guard, whom he found too violent and too brutal, and somewhere joined a detachment of Whites at the beginning of 1919. His mother, meanwhile, had died, but this appeared a matter of no concern to him. One of his half-brothers had been shot for commercial speculation, and another had become a member of the Cheka or secret police. Neither of these facts caused him the slightest anxiety; he communicated with neither brother and wandered about with merry unconcern, proclaiming the evils of Communism. With a White regiment he reached the outskirts of Theodosia, on the shores of the Black Sea.

At this point his wife, who had with the greatest difficulty traced his movements, joined him with their child. He expressed delight at seeing them and managed to get the White commander to quarter them in one of the unused flats deserted by the inhabitants in the port town. The little girl was visibly worse, and was in fact dying of the croup. Her mother, who had no eyes but for her husband, nursed her as well as a distracted, unpractical bluestocking could, torn between thoughts of revolution, the peasantry, the workers, the rival claims of Marxism and anti-Marxism, and her husband’s peculiar tergiversations between Reds and Whites. They discussed the possibility of joining the Green armies – wild marauding bands of peasants who belonged to an anarchist movement directed equally against Whites and Reds – and in the course of these discussions Asia, his daughter, died. Her mother was broken by this, but Landoberg appeared to feel little.

He developed an immense passion for music at this time, and when not marching or counter-marching listened to an amateur quartet, in which Nicolas Nabokov, later an eminent composer and writer on music, took part. Nabokov remembered him well as one of the small informal audience which gathered to listen to this quartet in the midst of the civil war on the shores of the Black Sea, and recollects that he was a man of irresistible spontaneity, warmth and charm.

Landoberg took part in several indecisive battles between Reds and Whites. Then one night, as he sat near a campfire with a small group of White officers, he listened to one of the staple themes of White soldiers – their hatred of the Jews as members of an international conspiracy, sworn to destroy Russia, murderers of the Tsar, to be exterminated at all costs, both in the immediate future and when victory was finally achieved over the forces of darkness.

This frightened him: there and then he determined to get away from these dangerous allies, and collecting his wife he bluffed his way into a ship carrying refugees from ports in the Black Sea to Turkey. It is not clear how he managed to make his way into a ship of this type without the necessary documents: but he was a man of infinite resource, and his artless charm, then and later, evidently melted the hearts of those in charge.

He determined to go to Palestine. He had never been a Zionist: indeed he had regarded that as a typical piece of bourgeois Jewish folly, an attempt on the part of victims to create a respectable liberal State or community, of the stuffiest, most Victorian type, and to perpetuate all the most philistine and socially mean and iniquitous characteristics of their oppressors. Nevertheless he suddenly decided that a new world was opening in Palestine for the Jews, rediscovered his Jewish origins and emotions, and joined the Zionist pioneer group Hechalutz in the Crimea. Inevitably, he became its leader after the celebrated soldier, Joseph Trumpeldor, who had organised Jewish self-defence against pogrom-makers in Russia, had left the Crimea for Palestine.

He landed in Jaffa at the head of a group of thirty-one pioneers at the beginning of 1920, with his wife and a small bundle of luggage, and two devalued Russian roubles in his pocket. They travelled with a collective visa granted by the British authorities. He later said that they represented themselves as returning refugees from Palestine; when asked how long they had been refugees, they replied ‘two thousand years’. This was very much in the spirit of Russian Zionists of those days.

In common with other immigrants they were taken to a Zionist reception camp. They were kindly treated and he was asked what profession he wished to choose. He indicated that physical labour was what he preferred. This wish was granted. He became a navvy engaged in breaking stones in a quarry. He is next heard of as taking part in the anti-British riots in Jaffa, together with the followers of the revisionist Jewish leader, Jabotinsky, whose by this time violent romantic nationalism was the very opposite of what Landoberg and his wife believed. However, where there was violence, thither he was irresistibly attracted. The British stood for all that was moderate, limited, dull, official, pompous and dead. Moreover they were for the most part pro-Arab and attracted by Middle Eastern semi-feudalism. The revisionists belonged to the extreme right wing of Zionism and stood for passion, militancy, resistance, self-assertion, pride and a nationalist mystique. He never actually joined the revisionists, and remained identified with the Haganah.

Landoberg was a man not permanently wedded to any ideal or any person. He changed his views, his mode of life, everything about himself, easily, with pleasure, delighting in everything new, exulting in his own capacity for beating any drum, wearing any suit of clothes, provided they were sufficiently gaudy – life was a carnival in which one changed one’s disguise to raise one’s own spirits and those of other people. He was duly arrested for taking part in the riots, and found himself in prison. Lady Samuel, the wife of the then High Commissioner of Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, was a prison visitor, and asked him what he had done. ‘I am Lady Samuel,’ she began. ‘I am Isaac Landoberg,’ he answered at once, and glared at her with amiable insolence. ‘What is your crime?’ she asked. ‘I fight for liberty everywhere,’ he answered. ‘All officials are my enemies. I fought with the Reds against the Whites, I fought with the Whites against the Reds, I fight with the Jews against the British. I am prepared to conceive that one day I may fight with the Arabs against the Jews, or anyone else.’ This was held to be inexcusable insolence. His sentence was doubled.

After his release from prison he broke stones to such effect that he was soon appointed manager of one of the quarries of the Jewish co-operative enterprise, Solel Boneh. His family had heard nothing about him. In 1924 he wrote a letter to my father, who by this time was living in London, saying that he was a happy, patriotic Zionist, with a bright future before him, urging all the members of his family to settle in this new and splendid land, where equality, fraternity and, one day, liberty would reign – a small country in which it was possible to do things impossible in larger, more unwieldy territories.

In the same year he appeared as the representative of the Palestine Jews in the Palestine pavilion at the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley. He was in the happiest possible mood. He visited my father and presented me, then a schoolboy, with a text of Ovid, whom he loved (Latin was among his few, curious scholastic attainments), and a book by Warde Fowler entitled Social Life at Rome in the Age of Cicero, which he thought a good book for a schoolboy to read. He was full of vitality, of wonderful talk; he had tremendous gusto and great charm; he was gay, insouciant and the most delightful company in the world. He taught us the latest Hebrew songs. He taught me a new tune for the song ‘B’tzet Yisrael mi-Mitzraim’ (‘De exitu Israel de Aegypto’,1 which has also been set by Mendelssohn in a very different fashion) and other new Hebrew songs, pre- and post-war. He talked with immense life and imagination, in the richest possible Russian, about a vast variety of subjects. I was completely charmed, and have remained so for the rest of my life. He invited the family to see the Palestine pavilion in Wembley. There we found him seated cross-legged on the stone relief map of Palestine – watched with fascination and horror by the representatives of the Palestine Arabs, who uncomfortably shared the pavilion with the Jews – eating sandwiches composed of Palestine produce, and drinking bottle after bottle of wine.

Unlike most of the Jews of his generation, he was a boon companion with an infectious wit and a most amiable disposition. His wife, gloomy, aware that her husband’s eye was straying elsewhere, not convinced of the value of Zionism, inasmuch as it was a nationalistic patriotic conception, not allied to the social-democratic ideals for which she had suffered in 1905 and which she still carried in her heart, tried to enter his moods of unrestrained gaiety, but did not succeed. This irritated him. He complained to my father about the arid, unimaginative, doctrinaire character of his sister, and said that if this situation continued, he would be forced, in the interests of his duty to his new country, which he must serve with all his heart, to leave her; unable to fly herself, she clipped his wings. My father reasoned with him, fearing what would happen to his sister if she were abandoned; she continued to love her husband with a most violent and ever-increasing passion, despite his lack of interest in her and complaints about her lack of joie de vivre.

After Wembley he returned to Palestine and continued in his quarries. In due course he abandoned his wife and took up with a number of other ladies who were only too delighted with the companionship of this attractive, unbridled, romantic figure of more than ordinary human size. His feeling about the Jews was, in a sense, wholly external; although he was one by birth and education, his behaviour was that of a happy fellow-traveller whom pure accident had brought to an unfamiliar shore, who found the people and their ideals sympathetic, so that although he did not feel bound to them by any profound emotion, despite the ties of blood, he was ready to collaborate with them and forward their ends with the greatest good will.

All this may have been transformed by the years during which no certain information about his psychological state can be obtained. His qualities of leadership, his reckless, lion-hearted courage, the total absence of any physical or any other fear (despite his flight from the Whites, which indicated that he had some self-protective instinct), his rich imagination and love of his fellows, his very childlikeness endeared him to many. Dr Weizmann, when he visited Palestine in 1936, had him assigned to himself as bodyguard, and found him an agreeable, lively and intelligent Russian, a welcome relief from the tense and worried faces he saw round him, and from the political problems and political intrigue to which he was normally condemned. They remained friends until the end. Not so David Ben-Gurion, who looked on him, mistakenly it seems to me, as a dangerous power-seeker.

His wife, despairing of recapturing his affection, returned to Moscow to her brothers, where she duly wore herself out in good works and faded towards an untimely death. His relations found it difficult to forgive Landoberg for abandoning her; judging him in terms of their own morality, they showed, as might be expected, blindness to his heroic attributes. He was a guerrilla by nature, and the rules of settled, non-nomadic populations did not apply to him. In the 1930s, when self-defence units among the Jews gradually coalesced into the Haganah – the underground Jewish army – he was a natural recruit and became its principal trainer in shock tactics. He was a chief architect of the Palmach – the force de frappe, the successor in 1941 of earlier units – which he saw as the heart of resistance, battling against alien rule. I imagine that the Arabs entered his mind no more than they did that of the Yishuv.

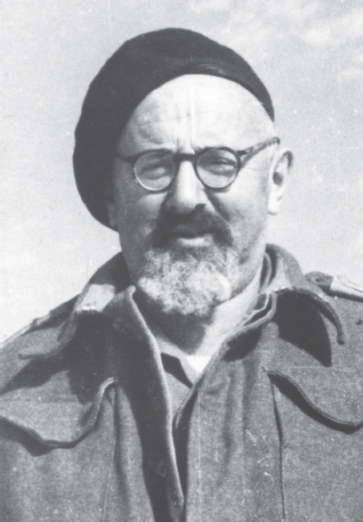

He became one of the principal leaders of the Haganah. At the outbreak of war he fought with the British Army (with which the Haganah was allied), was called ‘Big Isaac’, and fought the Vichy forces in Lebanon and Syria. After the war was over, he grew a beard, went into hiding, and took part in the Jewish resistance to the Mandatory British authorities. A price was put on his head, but he was never caught.

I had tried to find him when I went to Palestine for the first time, in 1934, but no one I knew could tell me where he was. He was presumably at this time engaged in creating the beginning of what later became the Palmach, but of that I was to know nothing at that time. I next met him in 1947, while I was staying with Dr Weizmann at Rehovot. Somehow the conversation turned on my relatives in Russia. I mentioned Yitzhak Sadeh (he had begun to use this name in 1938), and Weizmann said he knew him, and was greatly taken by him: he referred to him, with a smile, as ‘Reb Yitzhok’. The fact that Reb Yitzhok did not greatly care for David Ben-Gurion did not distress Weizmann too deeply. He said he thought he could find out where my uncle and cousin was. It was not too easy, because the Palestine police were looking for him. But I succeeded in meeting him clandestinely in the back of a cafe in Tel Aviv, and had a very good two hours with him. He was in the best of spirits. He told me about his exploits with the British Army. He assured me that no one would inform on him to the authorities. He proved right.

As for his relations to the British, he said that he had no feeling against them, he liked some of them and greatly admired their qualities; but since their policies were what they were, there was no alternative – they had to be fought tooth and nail. Submission to the Arabs – which the Colonial Office plainly wanted – was unthinkable. He said that the Palestine administration in the 1920s and 1930s really was too much for him: the officials, even when well-meaning and not overtly anti-Jewish or anti-Zionist, were too mean-minded, too pedantic, too narrow. Above all they were philistine; they lacked what he called genuine culture; with few exceptions, it was impossible to talk to them about books, ideas, music, history, particularly the long Jewish tradition with consciousness of which the Jews, of course, were filled. There was no contact: it was never and could never be a marriage, the sooner there was complete divorce the better – perhaps relations would improve after that.

When I first knew Sadeh, he was slender, elegant and had a certain pride in his appearance: now he was plump, had grown a beard, his clothes were ragged, and he plainly did not care what he looked like – he was totally uninterested in the amenities of life, what he adored was action – he enjoyed his hunted existence quite enormously. He was certainly a happy man when I met him in this cafe, with no sign of the slightest nervousness, fear or real concern about the future – every day brought its own problems, every day brought its own pleasures – he simply went from adventure to adventure with the greatest appetite for life.

In 1948, after the British left Palestine, he became a commander of a mobile unit, and captured Egyptian fortresses, and took prisoners. His method, as we learn from those under his command (for example, a grandson of the very Lady Samuel to whom he was so insolent), simply consisted of rushing Egyptian outposts with a grenade in each hand, shouting loudly and telling his men to do likewise. The Egyptians duly fled, leaving their shoes behind. Little blood was shed. He gathered up whatever weapons caught his eye.

The trophies he collected – guns, daggers, yataghans – afterwards proudly adorned his house in Jaffa. I met him there after the War of Independence. By this time he was something of a national hero. He showed me a great many photographs of himself in action against Egyptian troops and strongholds. When I told him that he was a kind of Jewish Garibaldi – the famous Italian national hero who fought the Austrians in the nineteenth century – he was delighted.

He turned out to know all about Garibaldi: his life and campaigns had always fascinated him, he said, and in the postcard he wrote me shortly afterwards he signed himself ‘Garibaldi’. He kept a goat tethered to a tree in the garden, not because he needed its milk, but simply because this was forbidden by the new Israeli laws, and he believed in defying idiotic regulations. He seemed to me totally unchanged. His by this time considerable fame had not gone to his head; he remained simple, informal, with an undiminished gaiety and verve, above all vitality, a love of life in all its phases, a love of action, a love of change, events, a love of whatever might happen, a hatred of peace and quiet and boredom and a settled life. He had a large bottle of vodka on the table – ‘I keep that for the Soviet ambassador,’ he said.

His part in Israeli politics had exactly the same quality of insouciance and irresponsibility as everything else that he did. Adoring children gazed at him rapturously in the streets. Fellow-travellers and Communists gathered in his Sabbath salon. He drank with members of the Soviet Embassy and wondered if he ought to pay a visit to Moscow to see what had happened in his absence. He explained his pro-Soviet attitude by his conviction that the Americans and British would never bomb Israel, but the Russians might: hence the need to keep in with them – he disclaimed ideological sympathies. He said to me in Jaffa: ‘The Russians would like a large Arab federation to include our little State – but that is impossible – we shall never be Communists. The Israeli Communist Party is a ridiculous party, and the Arabs will not be Communists either, whatever they may say. Good relations with the Soviet Union are possible, Communism never. Our problem is not political, our problem is relations with the Arabs, which is a moral and personal problem. At one time I believed in the possibility of a bi-national State of Jews and Arabs, but I see it is impossible – they hate us too much, and I quite understand that. We must live separate lives. Of course, we shall try to treat our Arab minority as well as possible, but I am afraid that will not reconcile them. Still, one never knows – the future is the future, all kinds of things can happen, one must not give up hope, above all one must not be afraid, one must simply regard everything as material out of which to build one’s life, and make it as rich and full as possible.’

He took particular pride in his friendship with his disciples, as he thought of them, Moshe Dayan and Yigal Allon, both of whom he adored – there is a famous photograph, at one time on public sale, showing him with his arms round the shoulders of the two warriors. He was determined not to be taken altogether seriously. He adored telling of his exploits, like a retired revolutionary Mexican general – but even then he displayed qualities of vanity so simple, and so attractive, that no one was moved to jealousy.

He was by this time happily married to a well-known partisan lady, having abandoned many others in his victorious course. He enquired tenderly, when I visited him, after his family, and regaled me with stories of his magnificent past. In a country filled with tensions and anxiety and earnest purpose, as all pioneering communities must be, this huge child introduced an element of total freedom, unquenchable gaiety, ease, charm and a natural elegance, half bohemian, half aristocratic, too much of which would ruin any possibility of order, but an element of which is something which no society should lack if it is to be free or worthy of survival.

He was one of life’s irregulars, wonderful in wars and revolutions and bored with peaceful, orderly, unexciting existence. Trotsky once said that those who wanted a quiet life did badly to be born into the twentieth century.1 Yitzhak Sadeh certainly did not want a quiet life. He enjoyed himself enormously, and communicated his enjoyment to others, and inspired them and excited them and delighted them. I liked him very much.

His exploits – his training of, and friendship with, other Israeli soldiers, his emergence as a legendary hero – are not part of this story: they belong to the history of the War of Independence and the foundation of the State of Israel. All I have attempted to do is to present some recollections of my close relation, and some facts about his early life. He was a generous and adventurous man who played his part in the history of his nation, whose weaknesses attracted me at least as much as his virtues, and to whose memory I dedicate this modest and deeply affectionate memorial. Zikhrono livrakha.2

Moshe Dayan, Yitzhak Sadeh and Yigal Allon at Hanita kibbutz, 1938

1 He did have a thirst for knowledge – he liked reading and study – and indeed became a student during his army days in the civil war: in 1918–20, at the University of Simferopol in the Crimea, he studied philosophy and linguistics, of all subjects.

1 I was taken to his wedding, but I am told that there were so many guests and the music was so loud that I burst into tears and said ‘I hate this screaming music’ [‘Ich hasse diese Schreiemusik’] and had to be removed. I never saw him on that occasion.

1 [‘When Israel went out of Egypt’. Psalm 114: 1.]

1 ‘Any contemporary of ours who wants peace and comfort before anything has chosen a bad time to be born.’ Leon Trotsky, ‘Hitler’s Victory’, Manchester Guardian, 22 March 1933, 11–12 at 11, reprinted in Writings of Leon Trotsky (1932–33), ed. George Breitman and Sarah Lovell (New York, 1972), 133–6 at 134.

2 ‘May his memory be blessed.’