Corpuscle

AT ST PAUL’S SCHOOL I was an absolutely normal schoolboy, not very good at classics, but I got a prize for an English essay.1 I took the Balliol scholarship exam in spring 1927. I did not get one. Then my school wrote to Balliol to ask whether they would take me as a commoner, and they declined – I was below their academic level. After this double rejection, in 1928 I put my name down for the Corpus group. I knew little about Corpus, and had no special feeling about it, for or against. I knew only that it was reputed not to accept boys from St Paul’s, looking on them as superficial, sophisticated, basically ‘unsound’: it had produced Chesterton and Compton Mackenzie – precisely what the College did not want. I went in for a classical scholarship, but was awarded a new one allocated to ‘modern subjects’ (a great departure for Corpus: it prescribed classical Mods2 followed by modern history – an experimental move).

I probably got in on the essay paper, writing on ‘bias in history’. We were a fairly sophisticated London school, we used to read highbrow journals, e.g. T. S. Eliot’s Criterion: that had recently published an anti-Western article by an Indian whose name I don’t recollect called ‘Bias in History’1 – the very title of the set essay – and I reproduced what I remembered of it, and was elected. About a month later I was summoned by Dr G. B. Grundy to call on him in a boarding-house in London. When I met him I was terrified. There rose before me a military figure, wearing a British Warm, with a stern look and manner. He said, ‘Your classics aren’t much use. Don’t do Mods, you’ll do badly. Do ancient history. I got you elected. I’ll look after you.’ So in 1928 I did Pass Mods and went straight on to Greats.

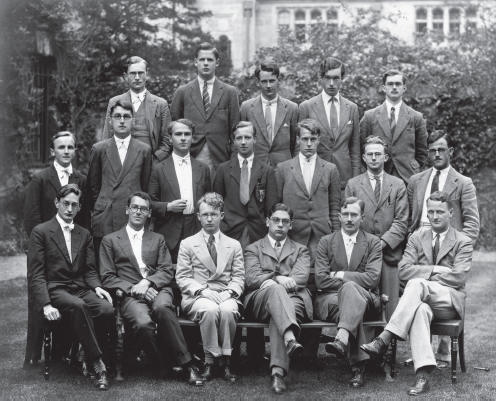

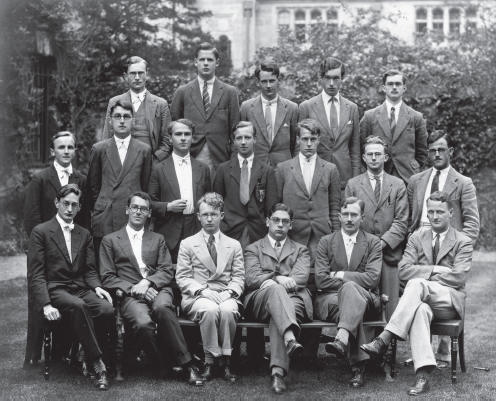

Members of the Pelican Essay Club, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, June 1930: (back) J. A. C. Cruickshank, J. P. Watson, P. G. Rendall, C. B. Spencer, D. H. Crofton; (centre) H. P. Kingdon, A. H. H. M. Dickie, G. L. Langford, W. H. F. Barnes, W. E. Stubbs, G. H. Andrew, K. D. Robinson; (seated) L. M. Styler, P. M. Crosthwaite, J. R. Liddell, IB, A. D. Dixon, M. St A. Woodside

I was fairly indolent as an undergraduate, and remained so for the rest of my life. But I’m by nature liable to anxiety, and lack self-confidence, and therefore I worked quite hard for my ancient history essays – but apart from that tended to stray from prescribed texts. I didn’t really take to ancient history. Grundy could not, by my time, be described as a good tutor. He was pretty old, and I used to go to his tutorials in Beam Hall (where he lived) with J. R. (Jock) Liddell, who fell asleep in one of Grundy’s tutorials, in front of a huge anthracite stove. Grundy noticed this, tapped him on the shoulder, and said, ‘I just wanted to ask when you wanted to be called.’ We copied the essays of men of an earlier year, to see whether we’d get a better or worse or the same mark. The marks were usually different. We didn’t do this consistently, only from time to time, experimentally. It gave us great amusement. He never discovered this. After reading one’s essay he would say, ‘Not bad – now let me tell you what you should have said.’ After his address, you bowed and left. He asked no questions. One was left more or less on one’s own; what one knew, one learnt from books and lectures. The best lecturers in this field in my time were Hugh Last and Theodore Wade-Gery. Marcus Niebuhr Tod was informative, but his manner was somewhat comical – it was difficult not to mimic him.

With philosophy it was very different. I did not get on with it at all to begin with, but I gradually became absorbed in it. Frank Hardie was a wonderful tutor. He taught me from the beginning to the end, from 1929 to 1932. He was young, shy, serious, kind, very sharp, not very good at introducing people to his subject. He was then a sceptical idealist of a Bradleian kind. He made one read Descartes, Bradley and Bosanquet, then Lowes Dickinson’s charming and useless book on The Meaning of Good1 – which did not work for me. I was made in my first term to read Bosanquet’s Logic;2 I felt what I imagined a football hearty might feel faced with Kant. For a long time I was completely at sea. But in the end I came round. Frank was so honest, so clear, so intelligent, so minute – he let nothing through – and a man of such impeachable integrity, so pure-hearted, that morally his tutorials had a wonderful effect. He was unbelievably careful, and cut everything into very, very small pieces. One always felt rather humiliated, because everything one wrote or said turned out to be superficial, vague, false, crude – but one learnt a very great deal. Hardie criticised and criticised, but he was extremely kind. He tried very hard to make one say what one really thought: ‘Do you really mean that? Might you mean that?’ His brother Colin came in during one of my tutorials and said in a shy manner, ‘Do you think we should go the whole hog or the half hog?’ Frank, after a long silence, replied, ‘Oh’, then silence; then, ‘I think half would be enough.’ Both spoke in very gentle, very Edinburgh accents, which I love to this day. Frank wore himself out as a tutor: he taught all day, his tutorials lasted for hours, he taught far too many pupils. But it was he who was responsible for the fact that Corpus produced an unusually high number of academic philosophers in the 1930s: in chronological order, Barnes, myself, Grice, Urmson, Wood, and I think one or two after that. Before his time, Corpus men notoriously failed to get firsts in Greats because they were taught by Grundy and Schiller, and the examiners didn’t like the results.

Grundy was extremely displeased at finding me turning into a philosopher. He said, ‘Really, there’s nothing in philosophy, it’s a perfectly empty subject, there’s nothing to it, really.’ He pressed me to combine the two by studying the Greek semi-philosopher Isocrates – ideas and classical history, he declared, combined the best of both worlds – but without success. I got a not very good First in Greats, but it was a First.

What next? I’ve never planned my life, but by my third year at Corpus I found that I was a committed philosopher, and decided to read PPE in my final year. Corpus was an exceedingly conservative college. PPE was actually forbidden. A mathematical scholar who insisted on doing it had his scholarship taken away. I was allowed to do it because I’d done Greats first; I’d fulfilled the duty of a gentleman. My stock went up further while I was doing Modern Greats, because I was the joint winner of the John Locke university philosophy prize. Politics was not taught at all. There was no tutor in it at Corpus, so I wasn’t sent to anybody – ‘Leading articles in The Times will give you all you need,’ I was told by the President. But I was sent for economics to a fellow of Queen’s, Lindley Fraser, who hardly taught me anything. I read Adam Smith, and Ricardo, and Marx: their principal works were set books. I learnt something from them, but I never learnt any later economics, and in the exam I simply reproduced propositions made by a Swedish economist I had come across, in the hope that the examiners might like it – I scarcely knew what these propositions signified. Still, I received a row of undeserved betas.

As an undergraduate I went to H. H. Price’s lectures, which were wonderful, and to H. A. Prichard’s lectures and classes. Prichard was a very clever man. Totally dogmatic. He started from some very naive premises, and then deduced, with great skill and ingenuity, various conclusions. The premisses were dogmatic, but the methods of argument seemed fascinating and convincing. In my third and fourth years I was invited to dinner or lunch by the leading younger philosophers, Price, Ryle, Mabbott. I emerged as a disciple of a pre-war Oxford philosopher, Cook Wilson – not favoured by Hardie, who was an idealist, whereas I became what was then called an ‘Oxford realist’. We discussed our divergent philosophical positions, but not sharply. There is a devious line of continuity from realism to logical positivism, though I never became a fully paid-up member of the new doctrine. During the war I moved away from metaphysics and the new philosophical orthodoxy to political theory and the history of ideas. And there I remained.

President Allen was a shy, remote scholar, gentle, unworldly and austere, like a learned monk. He had no secretary, no typewriter, wrote all his letters in a copperplate hand himself. The President’s breakfasts were somewhat awkward meals. The undergraduates summoned to them were told to come in ‘after Chapel’. He did not know how to talk to people. He would say, with an obvious effort, ‘If you were a millionaire, what would you do with your money?’ Silence. Someone would say, ‘I’d buy a yacht.’ ‘But supposing you had money left after the yacht, what would you do then?’ Someone else would say, ‘I’d buy Bulgaria.’ ‘Supposing the Bulgars refused to be sold?’ End of that subject. He was a conversation-killer, out of some kind of social despair. Mrs Allen did not make things easier. She was sweet, gentle, courteous, but had no more gift for conversation than her timorous cousin and husband.

I remember very well the first bump supper, which occurred fairly early in my career. The Allens thought that, to prevent the drunkenness and the unruly goings-on that they gathered were liable to take place, they would give a soup party at about nine in the evening – that might act to restrain the wilder spirits. My exact contemporary Kenneth Robinson, later headmaster of Bradford Grammar School, said, ‘Oh, Mrs Allen, I don’t think you’re pouring out that soup very skilfully, may I do it for you?’ Rather bewildered, she gave him the tureen: he then slowly poured the entire contents on to the floor. There was an awkward silence. He then knelt, stretched himself out on the floor, yawned and closed his eyes. He had to be carried out. Hamon Dickie, later a celebrated solicitor, then began to sing very loudly. At that point, someone hit him on the chest; he fell and crawled away on all fours. After that, the party was over. Then the JCR received a letter, solemnly read out, which said that throwing of bread during dinner must cease: the fellows found it disagreeable; it was insulting to be struck by a missile, and beneath their dignity to deflect it.

There was little entertainment by dons. Hardie was accessible, and we went to Salzburg together after I took Schools;1 but the only people who regularly entertained were Pidduck, the mathematical tutor, and the pragmatist Schiller. They gave breakfast parties on Sunday mornings which lasted for two hours at least – huge meals: kedgeree, kidneys, steak, mountains of eggs and bacon, sausages, anything might appear. Pidduck was an entertaining, bearded old gentleman, and talked non-stop, about his life, about William James (whom he knew well), about Oxford’s foolish philosophers and others, about everything. Pidduck wrote Oxford obituaries for The Times, and explained that when he changed his view of someone, he modified the text, usually pejoratively. As for the rest, Phelps was an intelligent man, clever and formidable, a personality of the first order. He liked gentlemanly games-players and disliked intellectuals and aesthetes. He was a snob of a straightforward old-fashioned British kind. His favourite old pupil, I remember, was a man called Robertson-Glasgow, whom he thought a perfect man. Henderson was the history tutor, a nice, civilised man who was bullied by Phelps, and up to a point by Grundy. We became friends. He died young. A. C. Clark, the Professor of Latin, was also a friend. He was old, eccentric and charming. I used to take him to the cinema. Everyone – Hardie, Ronald Syme particularly – mimicked his voice, which was unusually high. Typical quotations were: ‘I was staying in a hotel in Italy with a very pretty woman. She came down once and said she’d been bitten by a flea. I said “Oh fortunate creature!” ’; or ‘Fresh tomatoes can be a poem; stewed tomatoes are the lowest form of boarding house filth.’ Clark was a distinguished scholar, bored at being in Corpus. He used to come to lunch with me in All Souls; ‘I hate salt,’ he piped, ‘but I dote on pepper.’

Most of the College servants were charming. The first scout I met looked after the Corpus Annexe, where I lived before I moved into the second floor of the Gentlemen Commoners’ building – he was described in the by-laws as vir idoneus, a man fit for his job of looking after the Annexe. His name was Bancalari, brother of the scout in the senior common room. ‘Banky’, as he was called, was a gross, rude man who bullied the inhabitants of his building; he was rather obscene, and a reign of terror of a mild kind existed in the Annexe. If you came late, he wouldn’t answer the bell. He shouted curses at you for getting him out of bed, and complained to the Dean. He was very unpopular, whereas his brother Charles was gentle, sweet and very polite. ‘People think I’m Italian,’ Banky would say. ‘My mother used to work for – Webber’s. We wasn’t Italians.’ Latin verses were written about him: ‘non licet noctu vagari / e tutela Bancalari’.1 He had his favourites, of whom, it will be plain, I was not one.

Everybody in Corpus was expected to play all games because there were only eighty of us. I was not allowed to; because I had a bad arm, I was never bullied about that, or anything else. But one of my contemporaries, with whom I shared digs afterwards, was the College aesthete, Bernard Spencer, who became a well-known, much respected poet. I was woken one morning and invited to his bedroom. There were seven or eight ‘hearty’ Corpus men there. It was like seeing a murder, because he was in bed asleep. Suddenly the men fell upon him and cut off one of his whiskers. It was a horrible scene. Such attacks were not uncommon in other colleges, but much less so in Corpus, where a wide solidarity among the undergraduates existed.1 Nobody was hated, nobody was bullied. The incident with Spencer was not repeated. On the other hand, Corpus was a college where quest for prominence outside the College was slightly mal vu. For example, speaking at the Union was not well received. Getting a blue was not too good. If you wished to shine, you should do so in College, not outside.

Corpus in my time was a very tolerant society. I was excused Chapel, and nobody in Corpus ever, to my knowledge, referred to my Jewishness. I always feared I might as a scholar be asked to read grace in Hall. I wouldn’t myself have minded saying a Christian grace, but I thought that if anybody was truly religious they might not like sacred words spoken by a non-Christian. Corpus was rather inward-looking. The undergraduates were all a bit like dons and schoolmasters already. On the whole they tended to wear dark blue suits. There was not much temperament; the general atmosphere was of cosiness and friendship; it was an equal society – nobody stood out or dominated. I was perfectly happy at Corpus. Conversation in the JCR and in people’s rooms was lively and amusing. Everybody talked like mad. The President, I’m sorry to say, in his formal testimonial on me for the All Souls examination, said, ‘his rooms were a place of resort’ – I don’t know how he knew, but they were. My friends came from public schools as much as from grammar schools. There was no class feeling, none at all. I think I belonged to every society there was in Corpus. I made friends with almost everyone. I think I had what critics might call an undiscriminating taste in people.

I feel a deep loyalty to Corpus. Corpus shaped me in the sense that my total happiness as a member of it gave me a sense of security which I might not otherwise have possessed. I liked its tolerance, its comparative intellectual solidarity and its freedom from Bohemianism. The respect for learning was quite genuine, even on the part of people who were themselves remote from it; they did not mock or jeer at it. Nobody said to me, ‘Philosophy is about nothing much, a lot of rot.’ Not at Corpus – I heard something like this extensively elsewhere. If I’d gone to Balliol, I have no doubt that I might have emerged quite different.

It may be that being an outsider, with a sense of isolation, is a precondition of genius, and of all creativity. I can only confess that, for better or worse, I did not suffer this purgatorial experience. I was condemned to an uncritical sense of contentment, then and for many years thereafter.

1 [Probably the 1928 Truro Prize Essay (on freedom), which was published in shortened form in the Debater (St Paul’s School) no. 10 (November 1928), 3, and no. 11 (July 1929), 22, and reprinted as ‘Freedom’ in Flourishing (xxii/2), 631–7.]

2 [‘Moderations’, the first part of the classics syllabus. A shorter, unclassified version of this, ‘Pass Mods’, was available for weak linguists. The second part of the classics degree was ‘Greats’ – philosophy and ancient history.]

1 [Vasudeo B. Metta, ‘Bias in History’, Criterion 6 no. 5 (November 1927), 418–25.]

1 The Meaning of Good: A Dialogue (Glasgow, 1901).

2 Logic: or The Morphology of Knowledge (Oxford, 1888).

1 [Public examinations.]

1 [‘It is not permitted to wander at night, away from the protection of Bancalari.’]

1 [A modest academic controversy erupted on the incidence of such episodes in the Oxford Magazine. See A. F. L. Beeston’s letter in no. 76 (Michaelmas Term 1991, week 8), 18, followed by IB’s in no. 77 (Hilary Term 1992, noughth week), 8, where the Spencer episode is cited as one of four such episodes IB himself witnessed. See also Beeston in no. 79 (Hilary Term 1992, week 4), 15. Note by Brian Harrison, IB’s interviewer.]