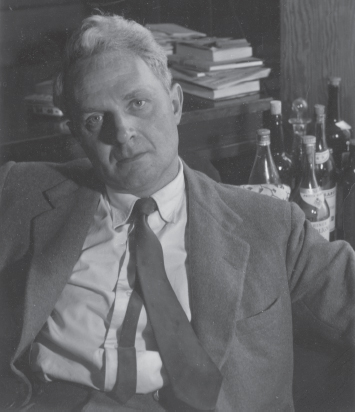

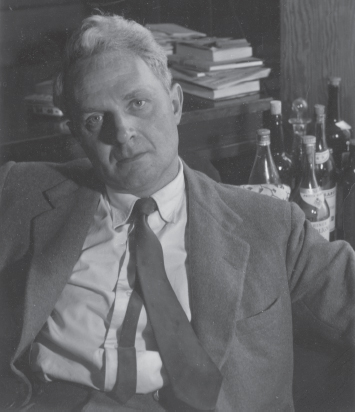

Stephen Spender in 1949

TO NATASHA SPENDER

1 August 1995

Headington House

Dearest Natasha:

When we met after Stephen’s funeral, I apologised for not having written to you. There seemed to me too much to say and I can only try to make up for not writing to you immediately by this probably quite long letter about Stephen, in particular the part he played in my life and the part that I, I think, played in his. In the course of our long lives (we were both born in the same year) we each had many friends and acquaintances, but our deep friendship was, I believe, a unique ingredient of both our lives, and never faltered, whether we saw each other or not.

We were divided by the war; he was in London, I in Washington – but when I came back it was exactly as it had been before, and so remained to the end. I think I first met him in Oxford late in 1929, or very early in 1930. I think the man who introduced me to him was my friend Bernard Spencer, a very nice, gentle, charming man, a good minor poet, who knew Stephen before I did. By that time the golden period of Oxford aestheticism was over: Harold Acton, Brian Howard, Cyril Connolly, Auden, Betjeman, Evelyn Waugh had all gone down. The dominant figure was Louis MacNeice, whom I did not know, and never – after I met him – entirely liked. Stephen knew him and tried to persuade us to feel sympathetic to each other, but it never worked, either way. Be that as it may, my first impression of Stephen was, as it remained, of a wonderfully handsome, friendly, open, gifted, disarmingly innocent, generous man, irresistibly attractive to meet and to know – indeed I remember vividly the sheer pride with which I could claim his acquaintance at that early period.

Stephen Spender in 1949

I saw him in Oxford from time to time. He read his poetry to me; I think his early verse, of those days, is among the best he wrote. We used occasionally to go for walks in Christ Church Meadow or the University Parks. I was, as during the rest of our lives, uniquely exhilarated by contact with him, and became devoted to him very soon indeed – and he, on his side, seemed to like me well enough to invite me to go and see him in London after he went down. I remember well his comical accounts of his academic life – the boring tutorials with his philosophy tutor E. F. Carritt: according to Stephen, after he read his essay Carritt would take out some notes, look through them, quote one or two things based on them, then say ‘That pretty well covers the field’, at which Stephen bowed, and left. What happened at the politics and economics tutorials I have no idea, he never mentioned them. He was extremely popular as an undergraduate: that is to say, he was equally happy in the company of aesthetes, contributors to the Oxford Outlook (of which I became editor) and rowing men, footballers and the like: they all fell under the spell of his great charm. In that respect, if in no other, he was unique – the gap between the ‘aesthetes’ and the ‘hearties’ was pretty wide at that time, and he alone, so far as I could tell, bridged it easily, unselfconsciously (and very happily – he liked liking even more than being liked).

Then I remember, before he went down (I don’t think he knew that he had not done well in his final examination), he asked his friends to come and see him in his rooms in St John Street – no. 53, I seem to remember. He told them that they could take with them anything that they found there – desks, chairs, tables, clothes, books, manuscripts, whatever there was – it was a general distribution of all his worldly goods. I remember Richard Crossman walking off with a book of manuscripts of Stephen’s poems. As for me, I think he gave me a book, I cannot remember what it was, I think a book of his early poems, inscribed ‘To Isaiah, this book made valuable by the author’, i.e. by bearing his signature. This sounds vain, but he was not given to any kind of vanity: he was neither modest nor vain, he was perfectly natural in all situations – he knew his own value, he did not exaggerate it, but neither did he underestimate it. And his comments on other writers – both senior to him, and influential, like T. S. Eliot, or his great friend and mentor Wystan, as well as later contemporaries, writers and artists of various kinds – were remarkably penetrating and sometimes devastating. Writers he reviewed and people he met sometimes took offence; yet in a sense he was more vulnerable than the people he saw through. In spite of wearing an air of a certain solemnity – in later life people thought of him, very falsely, as solemn, humourless, earnest, dreary – he was in fact sharply observant. His books of criticism, for example The Destructive Element,1 and his later ones too, are remarkably original and striking and above all penetrating; just as his comments about people were often very funny, almost always entirely valid and liable to hit the nail on the head, sometimes with almost too much force – that’s what made conversation with him not merely fascinating in general but extremely entertaining and delightful – in the way in which conversation with the very intelligent and observant Auden, or T. S. Eliot (whom I did not know well, but did know), was not. I remember meeting Auden at Stephen’s house in Frognal – it must have been about 1934; Auden took violently against me, I was everything that at that time he was against – middle-class, fat, conventional (he felt sure), bourgeois, obviously not homosexual, over-talkative; I met him again only in 1941, in New York, when we made friends and so remained for the rest of our lives. But to go back to Stephen.

Our love of music was an additional bond, particularly the chamber music of Beethoven. As you know, the late ‘posthumous’ quartets meant a great deal to him (too much, T. S. Eliot said to me, about Stephen), and that mask of Beethoven to which he wrote a poem came from a book I gave him, I think after he had gone down from Oxford. We both were transported by the performance of Beethoven’s sonatas by Artur Schnabel – word from a new world to both of us – we went to every single performance, I think, he ever gave in London. We went to every performance of the Busch Quartet, who were a kind of moral equivalent of Schnabel – they inhabited the same world. We were both great admirers of the conductor Toscanini. Music meant a very, very great deal to us both; we used to talk about it incessantly, and I think neither of us talked about it so often, and with such feeling, with anybody else (at least, that is my impression – perhaps he did talk to others about it also, but if so I never knew it).

Our moderate political views to a large degree coincided – we were both what might be called left of centre – Lib-Lab – typical readers of the New Statesman. Stephen was taken up by Bloomsbury, and Harold and Vita Nicolson – I remained remote from them. We were both deeply affected by the Hunger Marchers, by the Spanish Civil War, as so many of our friends and contemporaries were, by Fascism in Germany, Austria, Spain (for some reason Italy, although of course its regime was disapproved of, was somewhat regarded as more comical than tragic, perhaps wrongly). Stephen was deeply affected by his journey to Spain during the Civil War, to bring back one of his friends who went to fight for Franco but I rather think deserted and had to be rescued from danger from each side. I remember begging him most earnestly not to join the Communist Party, which I thought was not at all the kind of thing he believed in or would find himself comfortable in. But he insisted – his reason, I remember, was that everything else around us was decayed, soft, too flexible; that Communism was the only firm structure against which one could measure oneself (that was his phrase), and so find oneself, identify one’s personality and task in life. As you know, it lasted a very short time, and he rightly removed himself from the Party – I rather think that the head of the British Communist Party in effect told him that he was not one of them – rightly. His book Forward from Liberalism1 is perhaps the weakest of all his works, but it breathes the same air of sincerity, humanity, passion for the truth, decency, liberty and equality, not to speak of fraternity (which meant a great deal to him), as all his writings, at every period of his life.

I remember introducing Stuart Hampshire to him, I think in 1935, when Stuart was an undergraduate. I remember Stuart saying about him, as we walked away from the Spaniards Inn on Hampstead Heath, where we had met, ‘There is nothing between him and the object’ – i.e. his vision is direct, not mediated by anything, not framed by categories, preconceptions, a desire to fit things into some framework – direct vision, that was one of his outstanding and most wonderful characteristics, both as a man and as a writer. He was, I suppose, the most genuine, the most authentic, least arranged human being I have ever known, and that had an attractiveness beyond almost every other source of one’s sympathy, love and respect. Whatever situation he found himself in, his natural dignity and instinctive human feeling never deserted him – he was never a detached observer, never, I am happy to think, someone who looked upon men or situations with the cold, objective eye; he took sides; he identified himself with the victims, not the victors, without sentimentality, without tears, without feeling that he was behaving generously or kindly or nobly or importantly, without a dry sense of obligation – but with a kind of total commitment which moved me, I think, more than the character of anyone I had ever met.

One of his obituaries said that during the war he was a pacifist – I never knew that; I must admit that I do not believe it; his violent hatred of the Nazis, of Franco, of that whole horrible world, was so strong that I cannot believe that he was not prepared to fight against it – I think he was not conscripted because of some physical defect: his early illnesses must have left some indelible effect. He was exceedingly amusing about his life as a fireman during the war in London. I shall never forget his story about how the fire brigade to which he belonged, after the fires had ceased, continued to meet and, having nothing else to do, became a discussion group; somebody addressed it about India – a man at the back of the room said ‘We don’t want to hear about what to do about India, what we want to know is: who is to blame?’ – after that, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, dissolved these discussion groups.

I have said nothing about his experiences in Germany. As you know, he and his friends Auden, Isherwood, John Lehmann went to Germany and sometimes Austria, because the Weimar Republic and its cultural colonies seemed to them an ideal form of free existence, and the satisfaction of all their spiritual and physical needs. Nevertheless, even there his acute sense of the ridiculous – which was always present in him and which was one of his most delightful attributes – did not desert him: his experiences in Hamburg, on which his only novel, issued much later, was based – the embarrassing behaviour of his hosts, in particular of a man called Eric Alport (I rather think that he threatened to sue for libel if the novel was published, soon after it was written, in the early 1930s) – I myself read it at the time, with the greatest pleasure and amusement.

He was terribly bullied at that period by his great friends Auden and Isherwood; they were at that time totally opposed to what might be called middle-class culture – one was not allowed to like Beethoven, or Dickens, or Thomas Mann, certainly nothing by any French writer – only homosexual experiences counted, that alone was where salvation lay. Stephen was unsatisfactory in that respect: he did not accept or practice this particular doctrine, and so, on the island of Rügen in the Baltic, where they took their holidays, he was mercilessly persecuted about some of his bourgeois tastes. But he did not surrender – and his love of England, his natural patriotism, was in sharp contrast with the escape from the decaying Old World, from which his friends duly fled. Nevertheless they remained friends through it all. They lived in a world to which war, destruction, was inevitably coming, and everything that they wrote was conscious of that mounting cloud. I felt that myself, quite acutely, but as I was not an artist or a writer it did not affect my life or work as it did theirs; but I remained in sympathy with them, then and retrospectively.

After the war, when I came back from Washington and Moscow, where I had been as a servant of the government, Stephen had married you. His first marriage was a disaster: I have always blamed myself for having been party to it – I think that he met Inez at lunch with me, though I hardly knew her. It was over almost from the beginning, though when Inez left him he was very unhappy – humiliated, lonely and miserable, and his poetry of that date reflects all that very directly. But his marriage to you filled him with happiness – I remember those early post-war years very well, and he settled down, both to writing poetry and criticism and to working for the then wholly respectable (and in my view worthy) Congress for Cultural Freedom, an anti-totalitarian and in particular anti-Communist organisation – he settled down to all this very devotedly and successfully. I was not in England during the period when he and Cyril Connolly edited Horizon – a very remarkable achievement, particularly during a war – but I remember Encounter very well. Stephen never got on with the more fanatical co-editors of that journal, and I think he was really appointed in an attempt to make it – or at least make it appear – civilised, tolerant and liberal, and above all independent – which it later turned out it could never wholly have been, since it was supported by the CIA. Stephen’s enormous indignation and sense of betrayal when that fact became known was absolutely natural; I remember both you and he were in a state of anger and disarray when the trap into which he had fallen became discovered. His behaviour then and ever after did him nothing but moral credit.

Thirty years of close friendship followed. During that period I have nothing I can significantly add. He enjoyed being professor in UCL;1 he liked his journeys and lectures in the United States; he loved his children and they loved him. You created a framework in which he could live and flourish and be at peace, and be whatever he wanted to be. And our lives, as earlier, became interlaced: we saw each other frequently, as you know; and you were both part of Aline’s and my life, and we were, I sincerely believe, part of yours. I cannot even now bring myself to realise that I shall not see him again. His face, his figure, his voice haunt me, and will I expect haunt me till my dying day. I have never loved any friend more – nor respected, nor been happier to be his friend.

That is all I have to say. I expect I have left a great deal out, both of what I felt and of what he did and of what we did together and what we talked about – but at the moment nothing more comes to mind. Forgive me – this is all I can say at the moment. My memory in deep old age is none too good – forgive me for that too. I really have tried to do my best to convey what he meant to me – I wish I could do it more adequately – Stephen deserves better, but I am not gifted enough to do it.

Yours, with much love, from us both

Isaiah

PS My handwriting is mostly illegible – hence the typescript2 – I beg forgiveness –

1 The Destructive Element: A Study of Modern Writers and Beliefs (London, [1935]).

1 London, 1937.

1 [University College London.]

2 [This postscript is one of a number of manuscript corrections and additions.]