The Three Strands in My Life

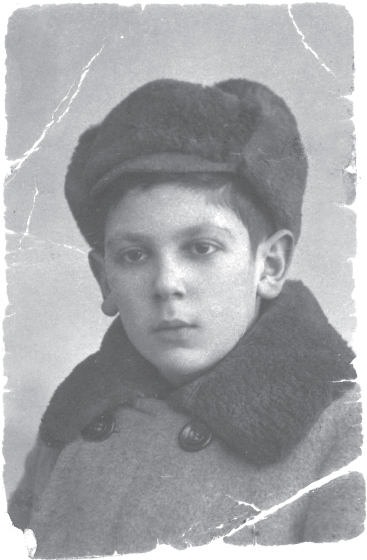

WHEN THE NEWS OF THE AWARD of the 1979 Jerusalem Prize became public, the Israel Broadcasting Service telephoned me in Oxford, and the interviewer asked me whether it was correct to say that I had been formed by three traditions – Russian, British and Jewish. I am not good at improvising answers to unexpected questions, and I was too greatly taken aback by this deeply personal enquiry to provide a coherent reply. I have never thought of myself as particularly important, or interesting as a topic for reflection, either to myself or others; and so I did not know what to answer. But the question itself lingered in my mind, and since it was asked, it deserves to be answered. I shall do my best to do this now.

I

To my Russian origins I think that I owe my lifelong interest in ideas. Russia is a country whose modern history is an object-lesson in the enormous power of abstract ideas, even when they are self-refuting – for example, the idea of the total historical unimportance of ideas in comparison with, let us say, social or economic factors. Russians have a singular genius for drastically simplifying the ideas of others, and then acting upon them: our world has been transformed, for good and ill, by the unique Russian application of Western social theory to practice. My fascination with ideas, my belief in their vast and sometimes sinister power, and my belief that, unless these ideas are understood, men can be their victims even more than of the uncontrolled forces of nature, or of their own institutions – these are reinforced daily by what goes on in the world. The French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, American democracy and American civilisation with its vast influence, the horrors of Hitler and of Stalin, the rise of the Third or decolonised World, of Islam, and the creation of the State of Israel – all these are transformations of world importance; and their effects in shaping men’s lives are not intelligible without a degree of insight into the social, moral and spiritual visions embodied in them, whether noble and humane, or cruel and odious – or a mixture of the two – always formidable, often dangerous, forces for good and evil or for both. That is an element in my conception of history and society which I owe, I believe, to my Russian origins.

The oldest and most obsessive of these visions is, perhaps, that of the perfect society on earth, wholly just, wholly happy, entirely rational: a final solution of all human problems, within men’s grasp but for some one major obstacle, such as irrational ideas in men’s heads, or class war, or the destructive effects of materialism or of Western technology; or, again, the evil consequences of institutions – State or Church – or some other false doctrine or wicked practice; one great barrier but for which the ideal could be realised here, below. It follows that, since all that is needed is the removal of this single obstacle in the path of mankind, no sacrifice can be too great, if it is only by this means that the goal can be attained. No conviction has caused more violence, oppression, suffering. The cry that the real present must be sacrificed to an attainable ideal future – this demand has been used to justify massive cruelties. Herzen told us long ago that sacrifices of immediate goals to distant ends – the slaughter of hundreds of thousands today that hundreds of millions might be happy tomorrow – often means that hundreds of thousands are indeed slaughtered, but that the promised happiness of the hundreds of millions is no nearer, is still beyond the hills. Acts of faith – autos-da-fé – when they inflict misery and savage repression in the name of lofty ideals, have the effect of removing all sense of guilt from the perpetrators, but do not lead to the blessed state guaranteed to result from, and therefore the justification of, the appalling means. When all is said and done, we are never too sure – not even the wisest among us – of what is good for men; in the end we can only be reasonably sure of what it is that particular societies of individuals crave for: what makes them miserable and what, for them, makes life worth living.

Men’s ultimate ends sometimes conflict: choices, at times agonising, and uneasy compromises cannot be avoided. But some needs seem universal. If we can feed the hungry, clothe the naked, extend the area of individual liberty, fight injustice, create the minimum conditions of a decent society, if we can generate a modicum of toleration, of legal and social equality, if we can provide methods of solving social problems without facing men with intolerable alternatives – that would be a very, very great deal. These goals are less glamorous, less exciting than the glittering visions, the absolute certainties, of the revolutionaries; they have less appeal to the idealistic young, who prefer a more dramatic confrontation of vice and virtue, a choice between truth and falsehood, black and white, the possibility of heroic sacrifice on the altar of the good and the just – but the results of working for these more moderate and humane aims lead to a more benevolent and civilised society. The sense of infallibility provided by fantasies is more exciting, but generates madness in societies as well as individuals.

An effective antidote to passionate intensity, so creative in the arts, so fatal in life, derives from the British empirical tradition. It was this civilised sense of human reality, a quality of life founded on compromise and toleration as these have been developed in the British world, that seemed so marvellous to the half-emancipated children of the oppressed and impoverished Jews of Central and Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century. I confess to a pro-British bias. I was educated in England and have lived there since 1921; all that I have been and done and thought is indelibly English. I cannot judge English values impartially, for they are part of me: I count this as the greatest of intellectual and political good fortune. These values are the basis of what I believe: that decent respect for others and the toleration of dissent are better than pride and a sense of national mission; that liberty may be incompatible with, and better than, too much efficiency; that pluralism and untidiness are, to those who value freedom, better than the rigorous imposition of all-embracing systems, no matter how rational and disinterested, or than the rule of majorities against which there is no appeal. All this is deeply and uniquely English, and I freely admit that I am steeped in it, and believe in it, and cannot breathe freely save in a society where these values are for the most part taken for granted. ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity’, said Immanuel Kant, ‘no straight thing was ever made.’1 And let me quote also the words of the eminent German-Jewish physicist, Max Born, who, in a lecture delivered in 1964, said: ‘I believe that ideas such as absolute certainty, absolute exactness, final truth and so on are figments of the imagination which should not be admitted in any field of science. […] [T] he belief in a single truth, and in being the possessor thereof, is the deepest root of all evil in the world.’1 These are profoundly British sentiments, even though they come from Germany – salutary warnings against impatience and bullying and oppression in the name of absolute certitude embodied in unclouded utopian visions. Wherever in the world today there is a tolerable human society, not driven by hatreds and extremism, there the beneficent influence of three centuries of British empirical thought – not, unfortunately, of a good deal of British practice – is to be found. Not to trample on other people, however difficult they are, is not everything; but it is a very, very great deal.

III

As for my Jewish roots, they are so deep, so native to me, that it is idle for me to try to identify them, let alone analyse them. But this much I can say. I have never been tempted, despite my long devotion to individual liberty, to march with those who, in its name, reject adherence to a particular nation, community, culture, tradition, language – the myriad unanalysable strands that bind men into identifiable groups. This seems to me noble but misguided. When men complain of loneliness, what they mean is that nobody understands what they are saying. To be understood is to share a common past, common feelings and language, common assumptions, the possibility of intimate communication – in short, to share common forms of life. This is an essential human need: to deny this is a dangerous fallacy. To be cut off from one’s familiar environment is to be condemned to wither. Two thousand years of Jewish history have been nothing but a single longing to return, to cease being strangers everywhere; morning and evening, the exiles have prayed for a renewal of the days of old, to be one people again, living normal lives on their own soil – the only condition in which individuals can live unbowed and realise their potential fully. No people can do that if they are a permanent minority – worse still, a minority everywhere, without a national base. The proofs of the crippling effect of this predicament, denied though it sometimes is by its very victims, can be seen everywhere in the world. I grew up in the clear realisation of this fact; it was awareness of it that made it easier for me to understand similar deprivation in the case of other people and other minorities and individuals. Such criticisms as I have made of the doctrines of the Enlightenment and of its lack of sympathy for emotional bonds between members of races and cultures, and its idealistic but hollow doctrinaire internationalism, spring, in my case, from this almost instinctive sense of one’s own roots – Jewish roots, in my case – of the brotherhood of common suffering (utterly different from a quest for national glory), and a sense of fraternity, perhaps most real among the masses of the poor and socially oppressed, especially my ancestors, the poor but literate and socially cohesive Jews of Eastern Europe – something that has grown thin and abstract in the West, where I have lived my life.

These are the three strands about which the Israeli radio interviewer asked me: I have done my best to answer her question.

1 loc. cit. (xv/1).

1 ‘Symbol und Wirklichkeit’ [‘Symbol and Reality’], Universitas, German edition, 19 (1964), 817–34, at 830.