Creator, Curator, or Caretaker—now that you have an idea of your overall objectives, it’s time to lay out the strategy that will help you succeed. Like any project manager, a step-by-step plan will move you forward toward your goal in a sequence of tasks without that “oops, I should have done this first” setback. It will also help you accomplish your organizing goals in a reasonable time frame. If you are like most people who inherit a family archive, you have a full-time job, a busy family life, volunteer responsibilities, and other interests. You are probably not a professional archivist, librarian, or museum curator (although you may be!). It’s not hard for “someone else’s stuff” to quickly drain your time and energy, leaving you feeling resentful and frustrated. A plan will keep you on schedule and minimize frustration. You can work on organizing your archive when you have time and energy, knowing you will eventually finish the project.

In this chapter, you’ll go through three more checkpoints:

Checkpoint 2: Set Your Goals and Time Line

Checkpoint 3: Inventory Your Archive

Checkpoint 4: Order Your Storage Supplies

You will be working with your archive, but you won’t be reorganizing or rearranging it just yet. The three checkpoints in this chapter lay the foundation for your organizing work by helping you to set a plan, identify the scope of the project, and gather the materials that you will need.

A good plan requires three things:

In checkpoint 2 you will identify each of these plan components.

In checkpoint 1, you wrote down your overall purpose for the archive; let’s work with those objectives to create a project plan. Transfer your objectives to checkpoint 2, available at www.familytreeuniversity.com/familykeepsakes, and add specific ideas or objects.

For instance, if your objective is to “Donate items to a research institution,” you might note: Donate great-great-grandfather’s Civil War letters to a library. If you are aware of libraries that might be interested, note them as possible options.

All project management includes a realistic assessment of available resources, such as manpower, funds, and information. The key word here is realistic. If you work full time and are a parent of young children, you may need to cut back your objectives or extend your time line to accommodate your situation. Retired seniors or full-time researchers may have more time available, but may choose to limit the number of hours they spend on archival projects.

People. List your name and the names of any other family members who you think might be interested in working with the archive. In chapter three, you will find ideas for pulling in assistance and sharing tasks.

Time. Next to each person’s name, indicate the amount of time per week they might be able to contribute to the project.

Funds. Give an estimate of how much money you have available for archival supplies. Use dollar signs if you don’t want to commit to figures. ($=low cost; $$=medium; $$$=expensive)

Information. Do you need to arm yourself with knowledge? Are you unsure of how to care for or store certain items? This book includes a detailed section on preservation and archival storage, with resources to help you locate further information. If you know you will be looking for places to donate artifacts, start collecting details on potential repositories. Likewise, make sure you know how to contact family members who might like to help with your archive or assume responsibility for some items.

If your entry hall or garage has been lined with boxes since the death of your grandmother, you may be ready to set a deadline of tomorrow! The size and scope of your archive will largely determine the time required to get everything organized and out of your living space.

If one of your main objectives is to make a photo book for an upcoming family reunion, use the reunion as a starting point. Figure out how much time you will need to create the book and have it printed: If you need one month, set your deadline one month prior to the reunion. Time management experts know that merely setting a deadline is the greatest motivator of all.

What can you do if the reunion is in only weeks away? You know that you can’t possibly organize the archive in a month, but you would still like to make that photo album. No problem. Set the photo book as a Milestone Goal, a mini-goal that moves you toward your overall objective but occurs sooner rather than later. In fact, this is probably the way most of us approach our work with a family archive.

I was in the midst of organizing my grandmother’s papers when my mom became ill and passed away. We wanted to assemble a photo slideshow for the memorial service, but I had barely started to look through boxes of old family pictures. I set aside my “organizing,” and narrowed my search to find photographs suitable for the memorial. The originals were scanned and returned to the boxes for “organizing” later. Don’t let the archive control you; remember, you are in control of the stuff.

Milestone Goals are also useful as mini-deadlines for large projects that can seem overwhelming.

Project creep is especially devious with family archives; before you know it, objectives expand, and more and more time is required until progress stalls or stops completely. It’s perfectly okay to adjust your objectives from time to time; but, adjust your resources accordingly and be realistic in your plans.

You might be ready dive in and start sorting and organizing your archive without looking back. If this is you . . . stop! Remember the Curator’s Commandment: Do No Harm. Those piles of papers and photos may seem completely disorganized; but in reality, there is no such thing as random order.

People categorize their things in many ways, from the simplest seemingly random piles, to elaborate filing systems. Your archive may be more organized than you realize. Personality, time available, resources, education, training, occupation, and family life all play a role in an individual’s organizational style. Some people think like office managers and file alphabetically and categorically, others sort by date or event, or even person. Any groupings at all can provide clues to unmarked or seemingly unimportant items.

Some of the most common groupings found in unprocessed family archives include grouping items by primary structure, such as the kind of material, date, or subject.

When items appear to be grouped at random, often a secondary scheme is at work. A death in the family may bring assorted photos out of different boxes and albums to assemble a collage for the memorial service, but the pictures may be returned to storage in one large packet. Likewise, baptism certificates are often needed for confirmation or marriage and may end up mixed in with other paperwork from that time.

Everything was a jumble inside my grandmother’s trunk. Grandma Arline liked to stash her memorabilia in old suitcases, and it looked like, at one time, the contents of each suitcase and box had been dumped directly into the larger trunk. Since then, things had been sifted and stirred by her daughters until it looked like one large pot of paper stew.

By the time I inherited the archive, the contents had already been moved to five cardboard cartons (another family member wanted to keep the trunk), further mixing up the materials. Any original order or groupings seemed to be lost. But as I began to work through the boxes just to evaluate the scope of the materials, I saw small packets and groups that had remained miraculously intact—envelopes filled with photos from an event, letters held together by a ribbon, bank receipts stuffed into a savings account passbook. Each group gave additional meaning to the items.

My grandmother’s archive appeared random, but it wasn’t. The remnants of groupings and sets show me that, at one time, she had things at least partially organized in a system that made sense to her. When I found nineteenth-century cabinet card photographs of two children labeled by name and a news clipping about those same children, I could assemble the story my grandmother tried to preserve. With a bit more detective work, I eventually determined that the young woman pictured in a second photo with the same children was Arline’s young cousin, the girl who had rescued the children from a winter blizzard.

Primary Scheme

Secondary Scheme

Now that you’ve considered the entirety of your archive and understand that its contents are not random, you can look through it to determine the kind and quantity of materials you are dealing with. Professional archivists might call this determining “Scope and Content.”

It’s time to open the trunk and see what’s inside those boxes. Use checkpoint 3, available at www.familytreeuniversity.com/familykeepsakes, to inventory your archive. The purpose of this preliminary survey is to get an overview of the size and scope of your archive. We won’t be sorting or cataloging today. We will use this information to

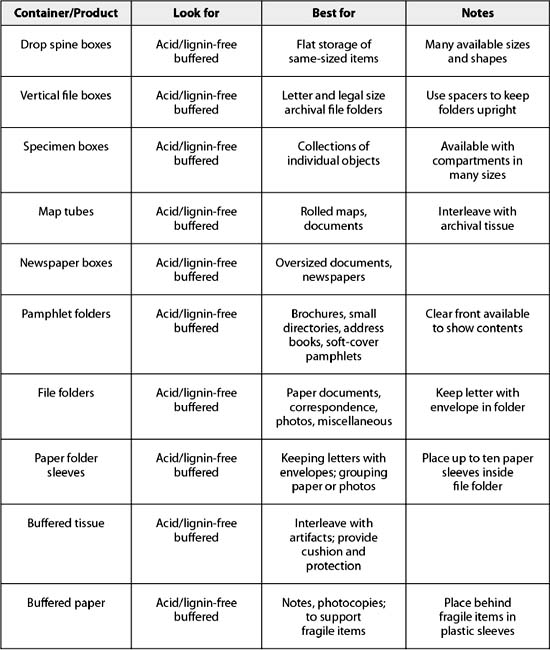

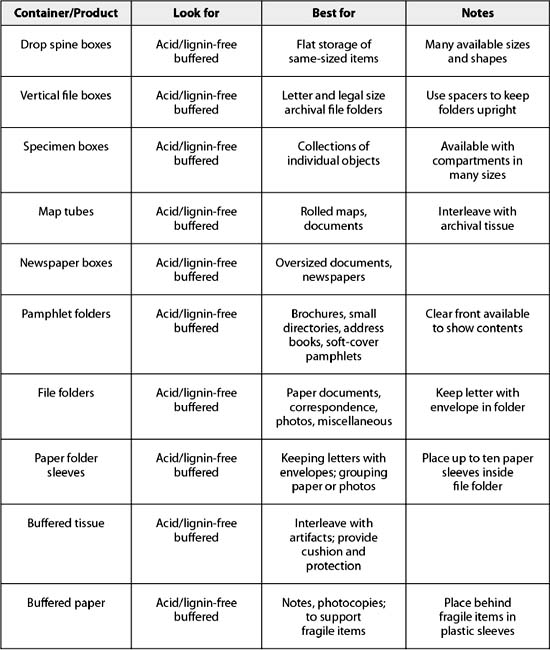

Now that you know the kind of materials you have, you can find or purchase containers that will help you properly preserve the items. Consider your budget and your goals. You may not have the resources to buy new containers for your archive. You might be able to find suitable containers already in your home. Follow these guidelines.

Your archive’s first line of defense against damage and deterioration is the box you select for overall storage. Containers should meet a few basic requirements:

For boxes, folders, mats, and other paper storage enclosures, “archival-quality” includes a tri-fold definition:

Look for items that meet all three requirements when shopping for storage containers for your home archive.

Have you heard the buzz about low-cost Riker Mounts? These clear front display boxes have been around for decades and are sometimes called “butterfly boxes.” They make anything inside look special, but beware. Typical Riker Mounts are not assembled with archival-grade materials. If you want the “Riker Mount look” for your family heirlooms, seek out specialty storage from an archival supplier. Select acid-free, lignin-free boxes with see-through lids. These containers are sometimes called artifact boxes, specimen trays, or window display boxes.

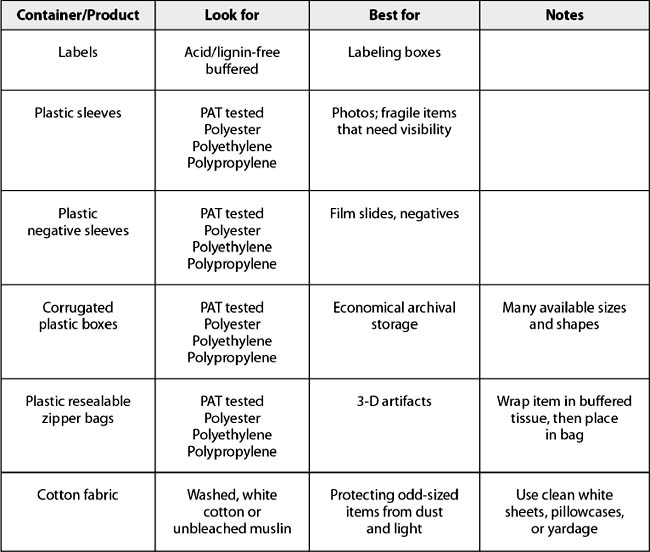

When selecting storage enclosures for photographs, choose paper and plastic materials that pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT). Use polyethylene and polypropylene products that are uncoated and made without plasticizers.

We know that wood pulp hastens deterioration, so it makes sense to eliminate or isolate any wood-pulp materials in your collection. This includes newspapers and any items printed on newsprint. You should be able to identify newsprint by its appearance, most often yellowed, brown, and brittle. Newsprint is highly acidic in nature due to the wood pulp used in its production.

Cotton or rag pulp, however, has proven to be a long-lasting substance. The survival of many old family letters and documents attest to the stability of good old-fashioned rag paper.

Preservation is all about slowing down the effects of time. It’s not possible to preserve materials for eternity at the original quality. The best we can hope to do is minimize deterioration and stabilize materials as much as possible.

The term archival-quality is used liberally by product manufacturers, and a product that is labeled “acid-free” doesn’t automatically meet true archival standards.

If you’ve ever seen a newspaper left out in the sun for a few days, you’ve seen the damaging effect light, air, and temperature has on paper made from acidic materials. Common newsprint is made from wood-based pulp products that are high in acid. Archival paper is made from cotton pulp and boasts a basic pH of 7 or higher.

Is acid-free the same as lignin-free? No. Lignin is a component of paper that can cause the formation of acid. Look for archival materials that are low-lignin or lignin-free.

Do my storage materials need to be buffered? Acid-free and lignin-free materials gain even longer shelf life when combined with a buffering agent, such as calcium carbonate during manufacture. This buffer helps neutralize acids that form over time. Some items, such as blueprints, drawings, and some photos can be damaged by the buffering component; they are better stored in neutral, or unbuffered, enclosures.

Do plastic sleeves and envelopes need to be acid-free and lignin-free? The archival terms “acid-free” and “lignin-free” don’t apply to plastic enclosures. Look for plastic products that pass the Photographic Activity Test (PAT). Archival plastic products include polyester, polyethylene, and polypropylene.

Many people mistakenly place their confidence in economical plastic bins for heirloom storage. Plastic is truly a wonder-material. It is lightweight, clear, waterproof, relatively inexpensive, and easily available. It can be a useful tool for storage under the right conditions. The bins do a great job keeping out dust, vermin, and moisture under average conditions, but they can also trap moisture inside where mildew and mold will quickly grow. Clear plastic stored on an open shelf is not a good choice for items damaged by exposure to light; however, a PET plastic container used to store something inside a closed box or closet might be a practical and suitable choice.

What should you do if the storage medium isn’t perfect? Use the best available at the time, and change storage methods when and if a better solution is discovered. Present archival practices recommend some types of plastic for certain storage situations, such as toys and crafts, as well as photographs or documents where viewing is desired.

When selecting plastic boxes, jars, bags, and envelopes, look for containers made from:

It is helpful to have some idea of how you want to organize your archive before you invest in too many boxes or folders. Typically, you will want to group materials by creator/author and by kind and size of material. For example, photographs should be stored with other photos of the same size, negatives should be stored together, and documents should be stored with other documents. Use checkpoint 4, available at www.familytreeuniversity.com/familykeepsakes, to help you select storage supplies.

Storage cases are made from different materials; always look for items labeled PAT certified, acid-free, lignin-free, buffered. Current products include:

Brodart <www.shopbrodart.com> (888) 820-4377

Gaylord <www.gaylord.com> (800) 962-9580

Hollinger Metal Edge <www.hollingermetaledge.com> (800) 862-2228

“Storage Enclosures for Books” leaflet and “Artifacts on Paper and Storage Enclosures for Photographic Materials” leaflet by Northeast Document Conservation Center <www.nedcc.org>

Sally Jacobs, The Practical Archivist <www.practicalarchivist.com>