Chapter 5:

I’m Jewish, but barely.

Both my parents are Jewish, but I grew up celebrating Christmas. Not in a religious sense. We didn’t celebrate Jesus being born in a manger, we didn’t go to midnight mass or sing carols or open the little flaps on an advent calendar. We decorated a tree and hung stockings and put cookies and milk out for Santa. That was the extent of it. We didn’t even sit on Santa’s lap at the mall.

My dad was orphaned by the time he went to college. His childhood was rife with death and loss. His parents had gotten divorced before they died, a fact that I was not even aware of until I was an adult and his sister told me. We didn’t talk about my dad’s family. We were his family: me, my brother, my mom.

Unlike us, what was left of my dad’s side of the family celebrated Jewish holidays. And we joined, on occasion. But not often. We only sat through a handful of Passovers at my Aunt Ruth’s. I never asked the four questions though. I didn’t know what they were. We never celebrated Hannukah, my brother and I didn’t have a Bar or Bat Mitzvah, and we didn’t go to synagogue. Ever. We didn’t own a menorah or affix a mezuzah to our front door to signal that ours was a Jewish home and that God was inside.

I knew I was Jewish, but I can’t say I knew what that meant. The strongest sense of Jewish identify I ever felt as a child was watching a mini-series called The Holocaust, in 1978. I was not yet ten, and I watched alone as the gaunt bodies lined up for food in the ghettos and then, later, were ushered to the gas chambers. It scared me. My mom found me sobbing in the den, but I couldn’t explain what had caused my breakdown. I understood vaguely that those people were my people. I knew we hailed from Russia and Ukraine but had been in America for several generations. I didn’t know anything else. I’m left wondering: Why didn’t I? Why didn’t we talk about it?

In college I often described myself as “culturally Jewish but not religious,” which to me meant: I liked corned beef sandwiches and Woody Allen movies, didn’t eat mayonnaise and favored bagels and lox if brunch was in order. And I laughed at things that I considered “goyisha,” which according to my dad was not having books in one’s house, and according to my mom was having bookless bookshelves filled with glass figurines of bunnies and garden gnomes, and giving daughters names like Tiffany and Courtney.

My mom’s father, Poppy, was an alcoholic, an enthusiastic gambler and a bookie. He ran the books out of the back of his dry-cleaning store in Atlantic City. My grandmother, Nanny, aspired to higher status, and she worked hard to keep up with the Joneses, which in Jewish neighborhoods in Atlantic City were Rosens and Maurers and Kleins. They were not dry cleaners, but jewelers and small-time real estate moguls and doctors. She was always perfectly coiffed, collected Ferragamo shoes stored pristinely in her closet, and saved money in a shoe box under the bed for rainy days when my grandfather’s luck ran dry at the craps tables. Which was often.

Nanny and Poppy had three children: my mom, my Aunt Jill, and my Uncle Bobby, who had severe Down syndrome. When pregnant with Bobby, my grandmother had been seriously ill, and sensed that something was wrong. She begged her doctor for what would then have been an illegal abortion. She was denied.

For several months after Bobby was born in 1952, no one knew precisely what was wrong. But he didn’t progress – he didn’t smile, hold his head up or meet other key milestones. Once doctors determined he had Down syndrome, he was both the all-consuming focus and the embarrassment of the household. This was close to forty years before the Americans with Disabilities Act. There were no support services for families with special needs children. Culturally, people with disabilities were often treated with either contempt or shame or both. Many families hid the children at home or hid them in facilities. My grandmother chose home. And she and my grandfather loved Bobby like crazy. But no one could come over. He was a secret to be concealed from the world.

Bobby required non-stop care and attention, and there was little left for the girls. My Aunt Jill was a star athlete, as much as was possible for girls in the 1950s. My mom was popular and pretty. She met my dad as a freshman in high school, and while she went to college and majored in biology, her professional life consisted of working in a lab to help put my dad through medical school. Then she had me, and she never worked again.

Nanny and Poppy came to our house on Christmas, pretended Santa had been to visit us, and brought gifts of their own. My dad’s family did not come for Christmas. I’m not sure they even knew we celebrated it – if so, they would not have been pleased. When my dad’s aunt announced that she was coming over to visit, we scurried to hide the tree in the backyard. I was confused. What’s wrong with a Christmas tree? Everyone has one! But we’re Jewish, my parents explained.

This begs the question: Then why do we have a Christmas Tree? I didn’t think to ask it.

Like so many other things, this just wasn’t discussed in my family. Why did we seem to pretend we weren’t Jewish? Why didn’t I know anything about my dad’s parents? Why didn’t we talk about Bobby? He was there when we visited my grandparents, he was obviously different, why didn’t anyone explain it to me? I didn’t know how to ask any of these questions, I just knew that there were certain things we weren’t supposed to talk about.

My junior year, I started at a new high school, my third school in as many years. I attended Allentown Central Catholic when I moved to Allentown to train in gymnastics, because there was a nationally recognized club there called Parkettes. I was a national team member when I headed to this club in 1983, ranked in the top ten in the country for my age. I hoped that they’d get me to the top six by the time I turned fifteen, so that I would qualify for competitions like the World Championships. They did.

First, I moved there on my own and lived with a coach. Eventually my mother moved with my brother, also a gymnast, and we lived in an apartment together. Later still, my father joined us, and commuted back and forth to his pediatric practice in Philadelphia.

Most of the Parkettes attended Allentown Central Catholic because they let us out early to train. We trained six, seven, sometimes eight or even ten hours a day in the summer. The public school didn’t allow anyone to skip gym or study hall. Which meant staying in school until 3:00 p.m. every day, missing two hours of practice, and being on the wrong side of our coaches before even setting foot in the gym.

It was 1985, and there was a gang of us that chose “Central.” Two of us were Jewish. My teammate Alyssa and I were the lone Jewish students roaming the halls of Central in the mid-eighties, in our pleated skirts and penny loafers. We all looked like sixth graders, stunted from enforced anorexia, and socially immature from doing nothing other than gymnastics for the last ten years of our young lives. Alyssa looked more typically Jewish than I did. She had darker hair and skin and a stereotypically “Jewish” nose; I was dirty blonde, pale with a button nose. I also weighed less than a hundred pounds, having dropped ten pounds (thus delaying my menstruation), upon starting to train at Parkettes a year earlier.

Allentown was not an enlightened place back then. It was a former steel town that had come on hard times as many rust belt communities had in the eighties, famously referenced in Billy Joel’s 1982 song “Allentown.”

When Alyssa got a note in her locker disparaging her Jewishness, threatening some vague violence if she didn’t get out, signed KKK, we weren’t alarmed, or even surprised. Whatever. We weren’t welcome there. We already felt unwelcome as tiny freaks, referred to as “Porkettes” by the cool/mean kids, a reference to how not porky we actually were.

Neither Alyssa nor I thought much of it, not even enough to tell our parents. We weren’t afraid (did these morons know the KKK hated Catholics also?). Still, I was relieved that they hadn’t come for me. I passed. They didn’t even know that I was Jewish. And I certainly wasn’t going to mention it. If my own parents didn’t embrace it, why should I? If we didn’t go to synagogue on High Holy days, or celebrate Passover, why did I need to open myself up to even more mockery and make myself feel like even more of an outsider? I mean I basically wasn’t Jewish. And if we didn’t regularly visit the practicing side of the family, there must be something shameful about being Jewish, right? So why not just keep the secret?

Though my husband Daniel is also Jewish, and not religious, his Jewishness is a major part of his identity. The dignity of difference, often strong in Jewish families, is something he and his family are proud of. I envy this pride in his heritage, this deep sense of history and strong connection to the past. For me, there was just my immediate family, in the right now, nothing more.

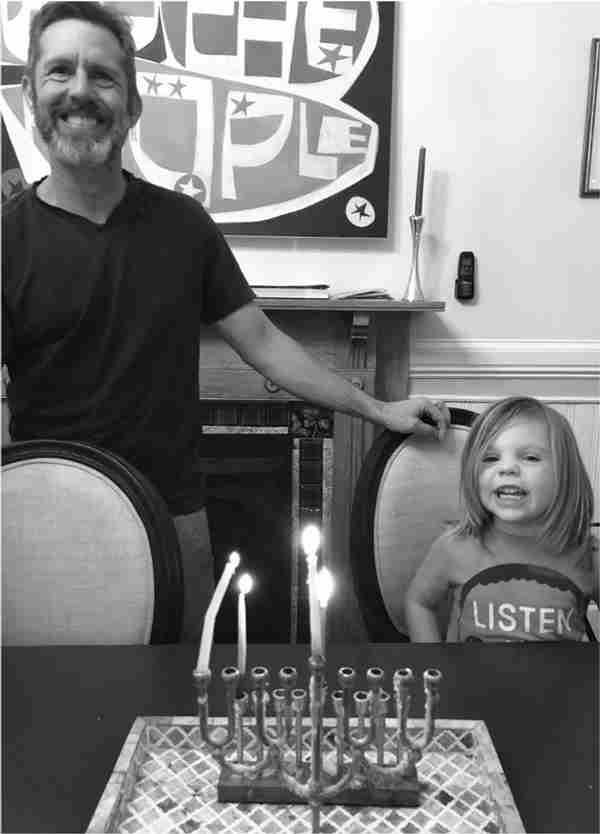

Since we met in 2012, I’ve adopted some Jewish practices, if not the faith. One of the few rules Daniel has in our house is no Christmas tree. Ever. We celebrate Hannukah every year, and each time, we light the candles on all eight days, and Daniel tells the story of how the Jews fought for freedom over two thousand years ago when they revolted against their oppressors.

Daniel and my third son, December 2017

Daniel often says I have less of a religious impulse than anyone he’s ever met. And he’s right. There is no part of my being that believes or wishes to believe in any higher power. I am neither religious, nor spiritual in a secular sense. I don’t like yoga or chanting or praying or seeking. I don’t like being told that there are fixed rules to being a good person. I prefer to make that calculation on my own. I’ve never wanted a framework from religion or any other organized group to tell me how to think, or how to be virtuous, or how to achieve the moral high ground. Perhaps that’s why it’s been easier for me to have rejected the dictates of the Left and the Democratic Party.

Yet it does seem to me that we all feel the need for guidance, and sometimes I do wish that I could embrace Judaism and find direction from an external source, as religious people do. Indeed, it is precisely because the need for a moral compass is so universal, that in an increasingly secular world so many seek desperately for other ways to find it – whether through political affiliation, blind adherence to “the science,” or self-help gurus.

As I’ve tried to teach myself a bit more about Judaism, I’ve learned about Tikkun olam, a central concept in modern Jewish thought. Tikkun olam, in Hebrew, literally means “repairing the world.” It teaches that we must behave constructively, through good deeds and everyday kindnesses, to make the world a better place. I didn’t know what it was until I was forty-two years old, but it felt like something I could get on board with when I happened upon it, more so than any other religious principle I’d ever encountered. Try to do good in the world in your daily existence. That’s it. And that’s all I want to try to do. A little good. Every day. In the world.

Which is sometimes very hard. But I keep trying.