For Germany, the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943 marked the turning point of the war. The Wehrmacht was badly overextended on all fronts. This first Allied penetration into “Fortress Europe” threatened to force Italy’s withdrawal from the war. The loss of 40 Italian divisions on occupation duty in Greece, Yugoslavia and southern France would oblige the Wehrmacht to replace them with German troops. The impending collapse of Italy prompted Hitler to call off Operation Zitadelle, the German offensive against the Kursk salient, on July 13, 1943. Germany lost the strategic initiative in the war and would be on the defensive ever after. Operation Husky alone was not responsible for this climactic turn in the fortunes of war. It was merely the culmination of a series of disasters that halted German momentum in 1943.

In spite of its ultimate strategic success, Operation Husky was controversial. Much of the early planning for the operation was hasty and slapdash, and there have been enduring arguments that other targets, such as Sardinia, would have been more fruitful objectives. The Allied advance on Sicily was frustrated by a relatively small German force, raising the issue of whether other tactical approaches would have been preferable. Most embarrassing of all, the Germans and Italians managed to evacuate much of their strength across the Messina Straits in spite of Allied naval and aerial superiority. For all the faults of its execution, the Sicilian campaign showed the growing abilities of the Allies in conducting complicated combined operations, a vital tactical skill that would be essential the next summer in Normandy.

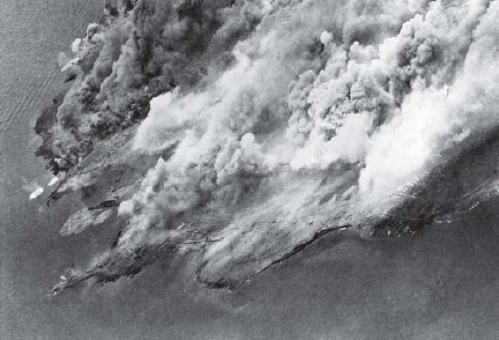

The military geography of Sicily is dominated by Mount Etna in eastern Sicily. This active volcano dominates the approaches to Messina, and this is a view of from the southwest in the area traversed by the British 13th Corps during the 1943 campaign. (US Navy)

The first few months of 1943 were a disaster for Germany, but even more so for Italy. Stalingrad was a well-known German defeat, but it is often forgotten that Italy’s forces in Russia were dealt a severe blow. The Italian 8a Armata ARMIR (Armata Italiana in Russia) lost 85,000 troops, with 20,000 dead and 64,000 captured. Further amplifying this catastrophe was the defeat of the Axis in Tunisia, which struck Italy far more severely than Germany.

The Allied victory in Tunisia in May 1943 opened the possibility of taking the war directly to Italian shores. Churchill was convinced that in the wake of the defeat of the Italian army in North Africa, a successful operation on Italian soil would knock Italy out of the war. Rome’s defection from the Axis camp would impact on the Wehrmacht as well. Of Italy’s 85 divisions, about half were stationed in Russia or the Balkans. While they were not equivalent to the German divisions in combat power, their sudden disappearance would force the Wehrmacht to move forces from other sectors to maintain the occupation in Greece and Yugoslavia.

Allied planning for a summer campaign began prior to the Tunisian victory, with a variety of objectives under consideration. The most obvious choices were Sardinia or Sicily. Sardinia was the more attractive of the two options if the Allied strategic plans anticipated an eventual invasion of the Italian mainland. The capture of Sardinia would place Allied forces opposite central Italy, threatening Rome itself. Sardinia would also place the Allies in easy reach of Corsica, a stepping stone into southern France or Italy’s industrialized north. In spite of these attractions, Sardinia posed a significant tactical problem for the Allies since such an operation would have to be conducted beyond the range of Allied land-based fighters. The Axis had demonstrated considerable skill over the past two years of war in the Mediterranean in frustrating Allied naval operations using land-based aircraft and, without the counterweight of Allied fighters, this threat dampened the appeal of Sardinia as the objective in 1943. Sicily was the other obvious choice in the Mediterranean and its southern beaches were within range of airbases on Malta.

The decision to attack Sicily was made in January 1943 at the Casablanca conference. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff under Gen. George C. Marshall had made clear their preference for a cross-Channel attack into northern France in 1943. The British chiefs under Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke contended that such an operation was premature until Allied forces were stronger. He forcefully argued that continued Allied operations in the Mediterranean were more feasible, would maintain the momentum in the region, and would force the Wehrmacht to divert additional divisions to this theater, thereby weakening defenses in northern France. Both sides agreed that some large operation would be needed to placate the Russians, who were bearing the brunt of the land war against Germany. In the end, Marshall agreed to continue operations in the Mediterranean in the summer of 1943 provided that they did not require the diversion of troops earmarked for the future cross-Channel operation. Since the US side would not commit to further operations in Italy after the summer 1943 landings, Sicily was the prudent choice, and a decision was reached on January 18, 1943. General Dwight Eisenhower was appointed to head the Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) for the campaign.

The Italian islands on the approaches to Sicily had been an aggravation to Allied operations in the Mediterranean through 1943. Mussolini had fortified the island of Pantelleria since the late 1930s as an Italian counterweight to the British garrison on nearby Malta. Italian propaganda trumpeted Pantelleria as the “Italian Gibraltar.” During the North African and Malta campaigns of 1940–43, the island had been a major airbase for German and Italian aircraft and its location midway between Tunisia and Sicily made it an ideal sentry to guard against the approach of an Allied invasion fleet heading to Sicily.

The Italian military garrison under Ammiraglio Gino Pavesi was 10,600 men, with a slightly larger civilian population. An assault on the island was opposed by the Allied army commander, Gen Harold Alexander, who pointed out that the island was ringed with rocky cliffs, with only a single plausible landing beach that was heavily defended. Nevertheless, Eisenhower wanted the island captured along with the smaller islands of the Pelagie group, including Lampedusa, as a prelude to any operation against Sicily. Radars on the island could track any Allied convoys heading to Sicily and the air and naval bases on the island continued to harass Allied convoys. Capture of the airfields on Pantelleria would also provide the Allies with extra airbase capacity closer to Sicily, and Malta was already overcrowded.

Operation Corkscrew depended on a massive aerial assault on the island to break the will of the garrison as a prelude to any landing. The bulk of the attacks were carried out by Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz’s North African Strategic Air Force (NASAF), which included four B-17 heavy bomber groups and five medium bomber groups, along with escort fighters. The campaign began on May 18 with daily medium bomber attacks, followed on June 1 by B-17 raids. By the end of the first phase of Corkscrew on June 6, NASAF had conducted more than 1,700 sorties and dropped 1,300 tons of bombs on the small island. The final phase of the air assault took place from June 7 until the scheduled assault landing on June 11, totaling a further 5,325 tons of bombs and 3,710 sorties. The air attacks were conducted around the clock with a special focus on coastal batteries. Starting on June 8, the Royal Navy began a bombardment from offshore. Surrender demands went unanswered so, on the night of June 10–11, the British 1st Division debarked from North Africa for an amphibious assault.

Operation Corkscrew was aimed at eliminating the threat posed by the fortified island of Pantellaria. The port area seen here was subjected to intense aerial bombardment during the final phase of the Allied bombardment from June 7 to June 11. (NARA)

As the Allied planners had hoped, the air attacks had severely demoralized both the civilian and military populations of the island. As disheartening as the bombardment was Rome’s refusal to send any aid, the island was expected to fight to the last without hope of reinforcement. On June 2, Pavesi informed Rome that the situation was hopeless and it was only a matter of time before the island was forced to capitulate. On the evening of June 10, before the arrival of the Allied amphibious force, Pavesi informed Rome that the island’s capacity to resist was practically finished. On the morning of June 11, Pavesi reported to the Supermarina, Italian Navy high command, that he would request surrender terms. The first Royal Navy warships appeared through the smoke around 1000hrs on July 11, but the landings waited until the smoke cleared. There was some minor firing as British landing craft approached the port, but the island surrendered without any significant fighting. Lampedusa and two small islands surrendered on June 12. The Allied seizure of the islands convinced Axis tactical commanders that Sicily was probably the next objective, but Rome continued to believe that Sardinia was next, and Berlin was convinced that Greece and Sardinia remained the targets.

One of the main Allied concerns for the Operation Husky landings was the threat posed by Axis airpower. The capabilities of land-based bombers and torpedo aircraft against maritime targets had been demonstrated time and time again in the 1941–43 Mediterranean fighting, and there was considerable anxiety over the vulnerability of the Allied landing fleets once they approached the shores of Sicily. In April 1943, Allied intelligence estimated that there would be 840 German and 1,100 Italian aircraft in the Sicily–Sardinia–Pantelleria region and that the landings would face attack by 545 German and 250 Italian aircraft. Intelligence assessments painted a grim picture of likely Allied losses, suggesting that as many as 300 ships were likely to be sunk. To preempt the Axis air threat, an air campaign against the Axis airfields was initiated in May 1943. Additional resources for these attacks came from a heavy influx of US Army Air Force (USAAF) bombers, including the diversion of B-17 heavy bomber groups that had originally been earmarked for strategic bombing missions out of Britain.

The first wave of air attacks in May 1943 was directed against airbases on Sicily and Sardinia and, through the course of the month, other major concentrations on the Italian mainland were also struck. Airbases in Greece were attacked to mask the actual objective of Sicily, as well as to maximize the attrition of the Luftwaffe’s forces in the Mediterranean in general. Besides the airfield attacks, other targets were struck, including the docks and ferry crossings on the Messina Straits that fed reinforcements to Sicily from the Italian mainland. The Husky plan called for a concentration on Sicilian targets starting on D-8 (July 2) with a substantial intensification on all Axis airbases in range of the island. These were conducted by day with USAAF B-17 and B-24 bombers and at night by RAF Wellingtons. The Luftwaffe responded at first by trying to shift operations to satellite fields constructed near the main airbases, but these were repeatedly struck as well. The main Sicilian airbase at Gerbini, along with its 12 satellite airstrips, were largely unserviceable by the time of the invasion and, of the 19 main Sicilian airbases, all but Sciacca and Trapani were severely damaged or abandoned. About three-quarters of Allied pre-invasion airstrikes were directed against Axis airbases, totaling some 3,000 tons of bombs. The Luftwaffe was forced to withdraw its bomber and fighter-bomber groups from Sicily by the second week of July. Total Axis aircraft losses on the ground during the bombing campaign were 227 aircraft destroyed and 183 damaged, including 113 destroyed and 119 damaged on Sicily.

Allied planning was heavily influenced by early intelligence forecasts, which suggested potentially catastrophic casualties from Axis air attacks. One of the prime culprits was the German medium bomber force based on Sicily and in neighboring areas of Italy, such as this Ju-88 of KG30, which was based in the shadows of Mount Etna in the Catania area at the various Gerbini airfields. (NARA)

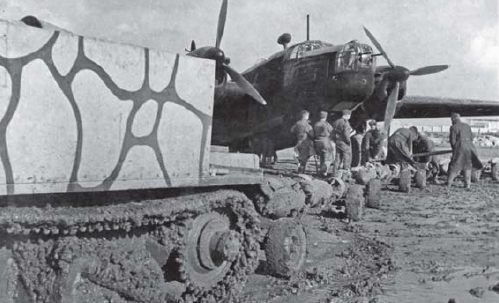

Malta provided an invaluable staging area for Operation Husky and served as the base for most air operations by RAF units. Wellington squadrons based on Malta were the primary night bombing force during the campaign. Here, a Universal Carrier is used as an impromptu tractor to tow bombs out to a Wellington during muddy weather. (NARA)